Abstract

Introduction and hypothesis

Pelvic organ prolapse (POP) is common and associated with sexual dysfunction. Vaginal pessaries are an effective treatment for POP, but their impact on sexual function is not well established. The aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to establish the impact of vaginal pessaries used for POP on female sexual function.

Methods

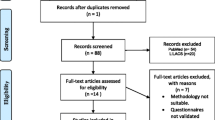

Systematic review of the literature following Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines and checklist. A comprehensive search was conducted across Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, EMBASE, MEDLINE, CINAHL, ClinicalTrials.gov, The WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform, ProQuest Dissertations & Theses, Open Grey and Scopus Citation Database. Randomised controlled trials and cohort studies that assessed sexual function in women pre- and post-pessary treatment for POP were included, assessed for risk of bias and their results synthesised.

Results

A total of 1,945 titles and abstracts were screened, 104 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility, 14 studies were included in the narrative analysis and 7 studies were included in the meta-analysis. The results suggest that, in sexually active women, there is no evidence of a deterioration in sexual function and some evidence of an improvement.

Discussion

This review offers reassurance that in sexually active women who successfully use a pessary for treatment of their prolapse, there is no deterioration in sexual function. There is some evidence of an improvement in sexual function, but given the clinical heterogeneity in the studies included, caution should be taken in generalising these findings.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Haylen BT, Maher CF, Barber MD, Camargo S, Dandolu V, Digesu A, et al. An International Urogynecological Association (IUGA)/International Continence Society (ICS) joint report on the terminology for female pelvic organ prolapse (POP). Int Urogynecol J. 2016;27:165–94. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-015-2932-1.

Swift SE. The distribution of pelvic organ support in a population of female subjects seen for routine gynecologic health care. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183:277–85. https://doi.org/10.1067/mob.2000.107583.

Nygaard IM, Bradley CM, Brandt DR, Women's Health Initiative. Pelvic organ prolapse in older women: prevalence and risk factors. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104:489–97. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.AOG.0000136100.10818.d8.

Fatton B, de Tayrac R, Letouzey V, Huberlant S. Pelvic organ prolapse and sexual function. Nat Rev Urol. 2020;17:373–90.

Jelovsek JE, Barber MD. Women seeking treatment for advanced pelvic organ prolapse have decreased body image and quality of life. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194:1455–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2006.01.060.

Lowenstein L, Gamble T, Sanses TVD, van Raalte H, Carberry C, Jakus S, et al. Sexual function is related to body image perception in women with pelvic organ prolapse. J Sex Med. 2009;6:2286–91. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01329.x.

Rogers RG, Pauls RN, Thakar R, Morin M, Kuhn A, Petri E, et al. An International Urogynecological Association (IUGA)/International Continence Society (ICS) joint report on the terminology for the assessment of sexual health of women with pelvic floor dysfunction. Neurourol Urodyn. 2018;37:1220–40. https://doi.org/10.1002/nau.23508.

Brown CA, Pradhan A, Pandeva I. Current trends in pessary management of vaginal prolapse: a multidisciplinary survey of UK practice. Int Urogynecol J. 2021;32(4):1015–22.

Rantell A. Vaginal pessaries for pelvic organ prolapse and their impact on sexual function. Sex Med Rev. 2019;7:597–603. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sxmr.2019.06.002.

Jha S, Gray T. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of native tissue repair for pelvic organ prolapse on sexual function. Int Urogynecol J. 2015;26:321–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-014-2518-3.

Antosh DD, Kim-Fine S, Meriwether KV, Kanter G, Dieter AA, Mamik MM, et al. Changes in sexual activity and function after pelvic organ prolapse surgery: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;136:922–31. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000004125.

Kearney R, Brown C. Self-management of vaginal pessaries for pelvic organ prolapse. BMJ Qual Improv Rep. 2014;3:u206180.w2533. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjquality.u206180.w2533.

Lough K, Hagen S, McClurg D, Pollock A. Shared research priorities for pessary use in women with prolapse: results from a James Lind Alliance priority setting partnership. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e021276. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-021276.

Roy Rosenzweig Centre for History and New Media. Zotero. Virginia: Fairfax; 2021.

Microsoft Corporation. Microsoft Excel. 2021.

Meriwether KV, Komesu YM, Craig E, Qualls C, Davis H, Rogers RG. Sexual function and pessary management among women using a pessary for pelvic floor disorders. J Sex Med. 2015;12:2339–49. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsm.13060.

Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Sterne JAC (editors). Chapter 8: Assessing risk of bias in included studies. In: Higgins JPT, Churchill R, Chandler J, Cumpston MS (editors), Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 5.2.0 (updated June 2017), Cochrane, 2017. Available from www.training.cochrane.org/handbook.

Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, Tugwell P. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses.

Constantine ML, Pauls RN, Rogers RR, Rockwood TH. Validation of a single summary score for the prolapse/incontinence sexual questionnaire–IUGA revised (PISQ-IR). Int Urogynecol J. 2017;28:1901–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-017-3373-9.

Kuhn A, Bapst D, Stadlmayr W, Mueller MD, Vits K. Sexual and organ function in patients with symptomatic prolapse: are pessaries helpful? Fertil Steril. 2009;91:1914–8.

Espitia De La Hoz FJ. Evaluation of quality of life in climacteric women with genital prolapse after the use of pessary. J Sexual Med. 2017;14(12 Supplement):e373–4.

Espitia F. Evaluación de la calidad de vida en mujeres climatéricas con prolapso genital luego del uso del pesario. Rev Colomb Menopaus 2018;24(4)::7–18.

Panman CMCR, Wiegersma M, Kollen BJ, Berger MY, Lisman-Van LY, Dekker JH, et al. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of pessary treatment compared with pelvic floor muscle training in older women with pelvic organ prolapse: 2-year follow-up of a randomized controlled trial in primary care. Menopause. 2016;23:1307–18.

Abdool Z, Thakar R, Sultan A, Oliver R. Prospective evaluation of outcome of vaginal pessaries versus surgery in women with symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2011;22:273–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-010-1340-9.

Albuquerque Coelho SC, Marangoni-Junior M, Brito LGO, De Castro EB, Juliato CRT. Quality of life and vaginal symptoms of postmenopausal women using pessary for pelvic organ prolapse: a prospective study. Rev Assoc Med Bras. 2018;64:1103–7. https://doi.org/10.1590/1806-9282.64.12.1103.

Anantawat T, Manonai J, Wattanayingcharoenchai R, Sarit-apirak S. Impact of a vaginal pessary on the quality of life in women with pelvic organ prolapse. Asian Biomed. 2016;10:249–52. https://doi.org/10.5372/1905-7415.1003.487.

Carlin GL, Morgenbesser R, Kimberger O, Umek W, Bodner K, Bodner-Adler B. Does the choice of pelvic organ prolapse treatment influence subjective pelvic-floor related quality of life? Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2021;259:161–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2021.02.018.

Fernando RJ, Thakar R, Sultan AH, Shah SM, Jones PW. Effect of vaginal pessaries on symptoms associated with pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108:93–9.

Lone F, Thakar R, Sultan AH. One-year prospective comparison of vaginal pessaries and surgery for pelvic organ prolapse using the validated ICIQ-VS and ICIQ-UI (SF) questionnaires. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2015;26:1305–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-015-2686-9.

Lowenstein L, Gamble T, Sanses TVD, van Raalte H, Carberry C, Jakus S, et al. Changes in sexual function after treatment for prolapse are related to the improvement in body image perception. J Sex Med. 2010;7:1023–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01586.x.

Mamik MM, Rogers RG, Qualls CR, Komesu YM. Goal attainment after treatment in patients with symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;209(488):e1–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2013.06.011.

Pezzella M, Iervolino SA, Passaretta A, Torella M, Colacurci N. Sexual function among women using a pessary for pelvic organ prolapse. Neurourol Urodyn. 2017;36:S5–87. https://doi.org/10.1002/nau.23302.

Radnia N, Hajhashemi M, Eftekhar T, Deldar M, Mohajeri T, Sohbati S, et al. Patient satisfaction and symptoms improvement in women using a vaginal pessary for the treatment of pelvic organ prolapse. J Med Life. 2019;12:271–5. https://doi.org/10.25122/jml-2019-0042.

Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1988.

Brincat C, Kenton K, Pat Fitzgerald M, Brubaker L. Sexual activity predicts continued pessary use. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191:198–200.

Hagen S, Kearney R, Goodman K, Melone L, Elders A, Manoukian S, et al. Clinical and cost-effectiveness of vaginal pessary self-management compared to clinic-based care for pelvic organ prolapse: protocol for the TOPSY randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2020;21:837. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-020-04738-9.

Bradshaw HD, Hiller L, Farkas AG, Radley S, Radley SC. Development and psychometric testing of a symptom index for pelvic organ prolapse. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2006;26:241–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443610500537989.

Price N, Jackson SR, Avery K, Brookes ST, Abrams P. Development and psychometric evaluation of the ICIQ vaginal symptoms questionnaire: the ICIQ-VS. BJOG. 2006;113:700–12. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0528.2006.00938.x.

Rosen R, Brown C, Heiman J, Leiblum S, Meston C, Shabsigh R, et al. The female sexual function index (FSFI): a multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. J Sex Marital Ther. 2000;26:191–208. https://doi.org/10.1080/009262300278597.

Rogers RG, Coates KW, Kammerer-Doak D, Khalsa S, Qualls C. A short form of the Pelvic Organ Prolapse/Urinary Incontinence Sexual Questionnaire (PISQ-12). Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2003;14:164–8; discussion 168. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-003-1063-2.

Rogers RG, Rockwood TH, Constantine ML, Thakar R, Kammerer-Doak DN, Pauls RN, et al. A new measure of sexual function in women with pelvic floor disorders (PFD): the Pelvic Organ Prolapse/Incontinence Sexual Questionnaire, IUGA-revised (PISQ-IR). Int Urogynecol J. 2013;24:1091–103. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-012-2020-8.

Baeßler K, Junginger B. Beckenboden-Fragebogen für Frauen. Aktuelle Urol. 2011;42:316–22. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0031-1271544.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L. Wharton: protocol and project development, data collection and management, data analysis, manuscript writing; R. Athey: data collection and management, data analysis, manuscript writing; S. Jha: data analysis, manuscript writing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1

Appendix 2: data extracted

Study characteristics:

-

Study ID

-

Author

-

Year of publication

-

Reference

-

Study period

-

Setting

-

Study design

-

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

-

Sample size

-

Follow-up period

Patient demographics:

-

Age

-

Parity

-

Sexual activity status

-

Prolapse details

-

Previous prolapse surgery

Intervention:

-

Type of pessary

-

Management of pessary (e.g. self-removal)

Outcomes:

-

Questionnaire used

-

Baseline score/post-treatment score/difference in score

Appendix 3

Appendix 4

Appendix 5: outcome measures

The SPS-Q [37] is a 25-part questionnaire assessing symptoms of pelvic organ prolapse (including sexual function), with each item scored on a four-point ordinal response scale (Never, Occasional, Most of the time, All of the time). Studies using this measure reported data on “Frequency of intercourse” and “Satisfaction with intercourse” as a change (Better, Worse, No Change).

The ICIQ-VS [38] is a 14-part questionnaire assessing vaginal symptoms (including sexual function). The sexual matters subsection can be scored to give an overall score of 0–58, with a higher score corresponding to worse sexual function. These scores have been reversed (multiplied by −1) in the analysis below to allow for comparison with the other measures.

The FSFI [39] is a 19-part questionnaire assessing symptoms of female sexual dysfunction across six domains (desire, arousal, lubrication, orgasm, satisfaction and pain). A score can be calculated for each domain, in addition to an overall score with a range of 2–36, where higher scores correspond to better sexual function.

The PISQ-12 [40] is a 12-part questionnaire with each question answered on a five-part Likert scale. A total score is calculated between 0 and 20, with higher score corresponding to better sexual function.

The PISQ-IR [41] is a 20-part questionnaire that includes subsections for both sexually active (with or without partner) and not sexually active women, covering a range of six domains for sexually active women (arousal/orgasm, partner related, condition specific, global quality rating, condition impact and desire) and four domains for not sexually active women (condition specific, partner related, global quality and condition impact). Domain-specific scores can be calculated and, in sexually active women only, a total summary score can also be calculated [19] with higher scores corresponding to better sexual function.

The German Pelvic Floor Questionnaire [42] is a 42-part questionnaire assessing symptoms across four domains of bladder function, bowel function, pelvic organ prolapse and sexual function. Each item is scored on a five-point Likert scale (0–4). The sum of each domain is divided by the maximum score and multiplied by ten, to produce a value between zero and ten for each domain, with higher scores corresponding to worse symptoms.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wharton, L., Athey, R. & Jha, S. Do vaginal pessaries used to treat pelvic organ prolapse impact on sexual function? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Urogynecol J 33, 221–233 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-021-05059-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-021-05059-4