Abstract

Introduction and hypothesis

Directed pushing while using the Valsalva maneuver is shown to lead to bladder neck descent, especially in women with urinary incontinence (UI). There is insufficient evidence about the benefits or adverse effects between the pushing technique during the second stage of labor and urinary incontinence postpartum. The objective of this study was to evaluate the effects of the pushing technique for women during labor on postpartum UI and birth outcomes.

Methods

Scientific databases were searched for studies relating to postpartum urinary incontinence and birth outcomes when the pushing technique was used from 1986 until 2020. RCTs that assessed healthy primiparas who used the pushing technique in the second stage of labor were included. In accordance with Cochrane Handbook guidelines, risk of bias was assessed and meta-analyzed. Certainty of evidence was assessed using the GRADE approach.

Results

Seventeen RCTs (4606 primiparas) were included. The change in UI scores from baseline to postpartum was significantly lower as a result of spontaneous pushing (two studies; 867 primiparas; standardized mean difference: SMD –0.18, 95% CI –0.31 to –0.04). Although women were in the recumbent position during the second stage, directed pushing group showed a significantly shorter labor by 21.39 min compared with the spontaneous pushing group: there was no significant difference in the duration of the second stage of labor between groups.

Conclusions

Primiparas who were in the upright position and who experienced spontaneous pushing during the second stage of labor could reduce their UI score from baseline to postpartum.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Pregnancy and childbirth are factors that contribute to pelvic floor disfunction (PFD). Thirty percent of postpartum women experience urinary incontinence [1, 2]. Most care for postnatal urinary incontinence is focused on treatment for PFD; however, pelvic floor muscles do not work alone, but work in cooperation with other muscles.

The whole abdominal cavity has been shown to work in conjunction with the pelvic floor muscles [3]. The abdominal cavity is referred to as the inner unit with the diaphragm on the upper side, the transversus abdominis muscle on the side, the multifidus muscle on the back side, and the pelvic floor muscles on the bottom side. All muscles are connected to each other [3,4,5].

Diaphragmatic motion is related to the contraction of the pelvic floor muscles [5]. The diaphragm is the muscle responsible for breathing, rising with exhalation and descending with inspiration. The pelvic floor muscles also move in conjunction with this movement, descending with expiration and rising with inspiration. Spontaneous pushing during labor involves natural exhalation within a short time frame of 6 s [6, 7] , whereas directed pushing involves consciously applying strong abdominal pressure and bearing down > 10 s or as long as a contraction continues [8, 9]. Generally, the average time for the second stage of labor is 1 or 2 h; during this time, women continue using either pushing technique [10].

If women continue to experience strong abdominal pressure such as that experienced during directed pushing for a long period of time, PFMs will loosen. Loosened PFMs cannot support pelvic organs such as the bladder, which leads to bladder descent and subsequently urinary incontinence [11]. Direct pushing like that involved when using the Valsalva maneuver is considered to cause damage to the PFMs.

In this study, we aimed to systematically review whether the pushing technique used by women in the second stage of labor affects postpartum urinary incontinence and birth outcomes.

Materials and methods

This study was registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic reviews (PROSPERO), with registration number CRD42017070826.

Search and selection of studies

We searched CINAHL, the Cochrane Library, EMBASE, MEDLINE, and PubMed on January 29, 2021, for articles related to postpartum urinary incontinence and birth outcomes when the pushing technique was used. We followed the Cochrane Handbook and Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines for reporting the review results [12]. There were no restrictions on the date/time, language, document type, and publication status. The keywords were identified from experts’ opinions, literature review, controlled vocabulary [CINAHL Headings; Medical Subject Headings (MeSH); Excerpta Medica Tree (EMTREE)], and reviewing the primary search results. We used Eisinga’s animal search filter to exclude non-human search results in EMBASE. Because of the poor reporting of outcomes in medical research, we did not limit the search in any way so as to enable us to obtain all search outcome results. The search strategies were developed with the assistance of a medical information specialist.

Eligibility criteria

-

(1)

Participants: These eligible women were primiparas at term during labor with a vertex singleton alive fetus and absence of complications. We excluded multiparous women and those with past history of urinary incontinence, anal incontinence, and pelvic organ prolapse and those who had caesarean section.

-

(2)

Interventions: Spontaneous pushing is defined as the naturally exhalation method where the woman pushes when she feels the urge. It includes delayed pushing and uncoached pushing.

-

(3)

Control: Directed pushing is defined as when women take a deep breath and hold it during the peak of contraction and then bear down and push for 10 s; this is repeated for the duration of the contraction. It includes immediate pushing, coached pushing, the Valsalva maneuver (pushing), and the breath-holding method.

-

(4)

Search strategy: This strategy was designed according to Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcomes, and Studies (PICOS) criteria as shown in Table 1. The types of studies included were individual and cluster randomized controlled trials (RCTs). Study design included RCTs.

-

(5)

The primary outcome was urinary incontinence. The secondary outcomes were perineal related, such as no suturing of the perineum, third- or fourth-degree laceration and episiotomy, and duration of the second stage of labor.

Study selection

We used Rayyan (http://rayyan.qcri.org), a free web application for speeding up the selection process of studies for inclusion within this systematic review. The search results were de-duplicated using EndNote χ6 and sent to two researchers for screening and confirmation. Two authors (KS, MS) independently screened all titles and abstracts so that non-eligible trials were excluded. When the two authors disagreed about study inclusion, other authors (EO, HE, SH) were consulted to obtain a consensus decision. All selected eligible studies were included in the present systematic review, and the appropriate data for statistical synthesis were included for the meta-analysis using Review Manager (RevMan) 5.4.1 (https://community.cochrane.org/help/tools-and-software/revman-5/revman-5-download).

Data analysis

We extracted both continuous and dichotomous data using Rev Man 5.4.1.

For continuous data, we calculated the mean difference with 95% confidence intervals (CI) for each study using the fixed-effect model. For dichotomous data, we calculated the risk ratio (RR) with 95% CI of each study using the fixed-effect model. We assessed heterogeneity using the 2 Chi2 and I2 tests. If multiple comparisons were made, only the groups that matched the intervention were selected and included in the statistical analysis.

Certainty of evidence was assessed using the GRADE approach [13]. The GRADE approach consisted of five domains, namely, study limitation (risk of bias), consistency of effect, indirectness, imprecision, and publication bias. A summary of findings included: change in urinary scores, urodynamic stress incontinence, no suturing, episiotomy, third- or fourth-degree laceration, and duration of the second stage of labor. The quality of the body of evidence was evaluated at four levels, namely, “high,” “moderate,” “low,” and “very low.”

Assessing risk of bias

Risk of bias was assessed by using the Cochrane Handbook risk of bias tool [12]. This assessment included seven items, namely, random sequence generation (selection bias), allocation concealment (selection bias), blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias), blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias), incomplete outcome data (attrition bias), selective reporting (reporting bias), and other biases.

Three authors (KS, MS, EO) independently judged the risk of bias of each included study. For any disagreements, the authors discussed the study until a consensus was made.

Results

Search results

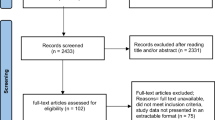

After duplicate studies were removed, 724 records were screened overall. A total of 658 records were excluded from the reviewed records because of the absence of RCTs, differences in the participants or interventions, or no outcomes data, as determined by Rayyan. From the remaining 67 appropriate studies, 51 were excluded because of the absence of RCTs, wrong participants, incorrect methods, wrong outcomes, and duplications. Seventeen RCTs with 4606 primiparas (2324 primiparas in the spontaneous pushing group and 2282 primiparas in the directed pushing group) met eligibility criteria for inclusion in our study. The selection process of studies is shown in the PRISMA flow diagram (Fig. 1).

Characteristics of included studies

The characteristics of the individual studies included are shown in Table 2. An RCT design applied included studies [14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30]. All studies characterized their participants as low-risk primiparas women at term with a singleton fetus and vertex presentation. The exclusion criteria were multiparous women and women with pregnancy complications [14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30].

Risk of bias in included studies

Risk of bias is shown in Fig. 2.

Most studies had a low risk of selection bias; however, the reporting biases of most RCTs were unclear as there was no included description. For the RCTs conducted in the 1980s and 2020s, there was insufficient information and lack of clarity regarding the selection bias and incomplete outcome data. The high risk of blinding of the outcome assessment was one bias because the investigator was not able to carry out blinding [17].

Effects of interventions

To estimate the effects of interventions, we clarified the overall certainty of evidence for each outcome using the GRADE approach (Table 3).

The results showed a very low certainty of evidence for the outcomes, change in the urinary scores and urinary incontinence. Regarding the perineal outcome, the certainties of no suturing and episiotomy were moderate. The duration of the second stage of labor showed a low certainty of evidence.

Synthesis of results

We compared spontaneous pushing and directed pushing. The primary outcome was urinary incontinence. There were three trials; two out of the three had continuous data and the other had dichotomous data.

For the continuous data outcome [18, 30], 867 women were participating, of whom 430 were in the spontaneous pushing group and 437 women were in the directed pushing group. The change in scores from baseline was significantly lower with spontaneous pushing compared with directed pushing (two studies; 867 primiparas women; SMD= –0.18 , 95% CI –0.31 to –0.04, ,p = 0.01, I2 = 0% ) (Fig. 3).

For the dichotomous data outcome [20], there were 128 participating women. Of these women, 61 women were in the spontaneous (uncoached) pushing group and 67 in the directed (coached) pushing group. The results showed no significant difference in urodynamic stress incontinence between the directed (coached) group and spontaneous (uncoached) group (RR 0.70, 95% CI 0.29 to 1.69, p = 0.443) .

For secondary outcomes, the results were as follows:

-

1.

No perineal laceration

Three studies reported dichotomous data [14, 23, 26] for no suturing of the perineum (Fig. 4). There were 341 participating women, of whom 169 were in the spontaneous pushing group and 172 were in the directed pushing group. Synthesis of the results showed a significantly increased difference in the risk ratio of no laceration of the perineum between the spontaneous pushing and directed pushing groups (RR 1.81, 95% CI 1.16 to 2.83, p = 0.009, I2 = 0%).

-

2.

Third- or fourth-degree laceration

Seven studies reported dichotomous data [14, 15, 17, 24,25,26, 28] for third- or fourth-degree laceration (Fig. 5). There were 2856 participating women, of whom 1442 were in the spontaneous pushing group and 1414 in the directed pushing group. Synthesis of the results showed no significant difference in the risk ratio of the third- or fourth-degree laceration between the spontaneous pushing and directed pushing groups (RR 0.89, 95% CI 0.71 to 1.13, p = 0.35 I2 = 0%).

-

3.

Episiotomy

Seven studies reported dichotomous data [14, 15, 23,24,25,26, 29] for episiotomy (Fig. 6). There were 2830 participating women, of whom 1417 were in the spontaneous pushing group and 1413 in the directed pushing group. Synthesis of the results of these studies showed no significant difference in the risk ratio of episiotomy between the spontaneous pushing and directed pushing groups (RR 0.96, 95% CI 0.88 to 1.04, p = 0.30, I2 = 30%).

-

4.

Duration of second stage of labor

Eight studies reported continuous data [15, 17,18,19, 21,22,23, 26] for the duration of the second stage of labor. Subgroup analysis was performed because the second stage of labor required labor changes owing to the effects of the maternal delivery position (Fig. 7).

There were 993 participating women, of whom 482 were in the spontaneous pushing group and 511 in the directed pushing group. There were 573 women in the recumbent position during the second stage of labor [17,18,19, 21, 22, 26], of whom 275 were in the spontaneous pushing group and 298 in the directed pushing group. There were 420 women in an upright position during the second stage of labor [15, 23], of whom 207 were in the spontaneous pushing group and 213 in the directed pushing group.

In the subgroup analysis of women in the recumbent position during the second stage of labor, those in the directed pushing group showed a significantly shorter labor by 21.39 min than those in the spontaneous pushing group [mean difference (MD) 21.39 min, 95% CI 16.53 to 26.25, I2 = 88%]. However, there was no significant difference in the duration of the second stage of labor between the groups in the upright position (MD 0.62 min, 95% CI –6.06 to 7.31, I2 = 90%). Synthesis of the results of these studies showed that the duration of the second stage of labor in the directed pushing group was significantly shorter by 14.21 min than that in the spontaneous pushing group (MD 14.21 min, 95% CI 10.27 to 18.14, I2 = 95.9%).

Heterogeneity

I2 for urinary incontinence and perineal outcomes such as no perineal laceration, third- or fourth degree laceration and episiotomy was 0–30%, indicating low heterogeneity.

Based on the results (Fig.7) of duration of second stage of labor, the total I2 was 95%, indicating high heterogeneity, even though the I2 values of the subgroups were 88% and 90%, respectively.

Because of individual differences in the duration of the second stage of labor, it is considered that the time to carry out the specific delivery position or posture cannot be unified.

Discussion

Summary of the main results

The synthesis of the results revealed that spontaneous pushing in the second stage of labor statistically reduces the change of scores for urinary incontinence from baseline compared with directed pushing. Although the meta-analysis resulted in a SMD between both groups of –0.18 95% CI, –0.31 to –0.04, we recommended viewing this result with caution, because there were few studies with small sample sizes investigating the relationship between pushing technique and urinary incontinence. Urinary incontinence is a disorder of the pelvic floor muscles. Applying repeated strong abdominal pressure several times as during directed pushing in the second stage of labor can lead to loosened PFMs. The loosened PFMs can cause pelvic organ problems such as bladder descent, which can also lead to bladder neck descent (BND) and its obtuse angle. BND can lead to BN becoming funnel shaped, which can then cause urinary incontinence. Women with urinary incontinence showed BN funneling upon transperineal ultrasound [31, 32]. Valsalva maneuver caused significant descent and movement of the BN in postpartum women with and without stress urinary incontinence after 6 months [33]. The average time of primiparas in the second stage of labor is 1 or 2 h, and contractions occur every 1 or 2 min. Women must repeat pushing several times during the second stage of labor. Repeated strong abdominal pressure can lead to BND, which can cause postpartum urinary incontinence. Even though women without UI conducted Valsalva maneuvers like directed pushing, their BN showed descent compared with rest by ultrasound [34, 35].

Regarding disorders of the pelvic floor muscles, in addition to urinary incontinence, perineal outcomes can also be considered. These may include an intact perineum (no suturing of the perineum), perineal laceration, and incised perineum and posterior vaginal wall because of episiotomy. Based on the results of this study, spontaneous pushing was found to significantly decrease the requirement of women needing sutures and result in no significant differences between the third- or fourth-degree lacerations and episiotomy incisions required. Spontaneous pushing involves natural exhalation breathing, so it can be considered not harmful for the perineum or PFMs. Directed pushing might be harmful and can cause damage to the PFMs, but is not harmful enough to cause third- or fourth-degree lacerations.

The duration of the second stage of labor was significantly shorter by 18.25 min in the directed pushing group compared with the spontaneous pushing group. Notably, the maternal delivery position greatly affects the duration of the second stage of labor and pushing. Specifically, the recumbent (horizontal) position makes it difficult to utilize gravity and could prolong the duration of the second stage of labor. The upright position makes it easy to exploit gravity and tends to shorten the duration of the second stage of labor. Therefore, subgroup analysis by maternal delivery position is required. The subgroup analysis showed that the duration of the second stage of labor for the spontaneous pushing group in the recumbent position was significantly longer by 21.39 min compared with that in the directed pushing group. However, the duration of the second stage of labor when women were in the upright position was not significantly different between both pushing groups. According to the results, spontaneous pushing in the upright position could help fetal descent and avoid too strong pushing.

When identifying disorders of the pelvic floor muscles, it is necessary to also consider the maternal delivery position in the future. Spontaneous pushing results in no suturing, as well as no significant difference in urinary incontinence or third- or fourth-degree laceration. Gupta et al. compared the occurrence of third- or fourth-degree laceration between the upright position and the horizontal positions of women in the second stage of labor [36]. They found no difference in the number of third- or fourth-degree perineal lacerations between women laboring in the upright and recumbent positions.

The results showed that spontaneous pushing does not cause stress to the perineum as the fetus slowly descends during the second stage of labor. Even though fetal descending takes time, it can be inferred that it does not cause any serious effects to the PFMs.

Certainty of evidence

Using the GRADE approach, the results showed a very low level regarding the outcome of urinary incontinence. This is because of the small trials and small sample sizes, making imprecision a serious issue. In future studies, more reports and larger sample sizes must be assessed using the same measurement tools.

For the duration of the second stage of labor, there was serious inconsistency because the I2 value was 95% or the heterogeneity level was high. These studies also used a questionnaire for pain or fatigue evaluation.

Regarding suturing, the small trials and small sample sizes increased the imprecision of results. Many perineal outcomes are listed only as lacerations. In the future, research should also describe the no suturing outcome. Third- or fourth-degree laceration was not significantly different between the spontaneous pushing and directed pushing groups: this result was the same as that found by Lemos et al. [37].

The present systematic review also included the aspect of anesthesia delivery. If anesthesia delivery data were not included, there would be considerably less research, which would limit the generalizability of this review. For Asia and Africa, the generalization of the present systematic review is limited because anesthesia use during delivery is not common. In the future, it is desirable to distinguish between race and anesthesia delivery.

Implication for further research

As pushing during delivery is closely related to the delivery position, we recommend conducting studies about pushing during labor and investigating its association with delivery positions. Heterogeneity of such studies is high because there are many types of delivery positions and women delivering babies cannot maintain one position for a certain period of time during labor. Furthermore, it could be unethical and impractical to make a woman maintain one position for a certain period of time during labor. To achieve lower heterogeneity, we recommend classifying the delivery positions during labor generally as vertical and horizontal positions, as gravity influences pushing. It is necessary to let women decided what position they would like to take during labor and analyze how long they maintain that position.

Limitations

One limitation of this research was that the trials investigating urinary incontinence and the sample size used were small. Also, the duration of the second stage of labor was associated with the degree of heterogeneity. Therefore, in the future, it will be necessary to increase the number of samples of women with urinary incontinence, and the analysis should include maternal delivery position.

Of the studies included in the analysis, 11 were conducted in the US, 5 in Europe, and 1 in the Middle East. No studies were conducted in Asia, Africa, or Latin America. Race was not described, but it is estimated that most of the women were Caucasian. However, as Asians are prone to perineal lacerations, their data need to be added to the results and analyzed in future studies.

The participants in this review were limited to primiparas as parity is a factor in urinary incontinence. Regarding the interventions, a comparison was made between spontaneous pushing and the Valsalva maneuver. Both methods are general pushing techniques that are preformed by women in the second stage of labor worldwide. Spontaneous pushing included delayed pushing or uncoached pushing, which involved no holding of the breath and waiting until the urge to push was felt. Directed pushing included immediate pushing or coached pushing, which involved consciously holding the breath for as long as possible. Even though conceptually the same, it appears that the methods differ slightly depending on the individual study. Thus, this seems to result in heterogeneity.

Conclusions

Spontaneous pushing has the advantage of reducing the score from baseline to postpartum and increasing the instances of no suturing of the perineum. There was no significant difference in perineal laceration, third- or fourth-degree laceration, or episiotomy between the spontaneous pushing and directed pushing groups. In addition, directed pushing was assessed to have no serious perineal effects.

Although it has the disadvantage of significantly prolonging the duration of the second stage of labor by 18.25 min, in the subgroup analysis, there was no significant difference in the duration of second stage of labor between the groups when women were in the upright position.

The overall certainty of evidence for change in urinary scores, urodynamic stress incontinence, and duration of the second stage of labor was assessed as low, and no suturing, third- or fourth-degree laceration, and episiotomy were assessed as moderate.

In conclusion, primiparas laboring in the upright position using spontaneous pushing during the second stage of labor could reduce their urinary incontinence score from baseline to postpartum by using this birthing position.

In future, more studies with larger sample sizes must be conducted to compare the concerted pushing styles and measurement tools.

Abbreviations

- PFM:

-

Pelvic floor muscle

- PFD:

-

Pelvic floor disfunction

- BN:

-

Bladder neck

- BND:

-

Bladder neck descent

- UI:

-

Urinary incontinence

- SMD:

-

Standardized mean difference

- RCT:

-

Randomized controlled trial

- RevMan:

-

Review manager

- GRADE:

-

Granding of recommendations, assessment, development, and evaluation

References

Thom DH, Rortveit G. Prevalence of postpartum urinary incontinence: a systematic review. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2010;89(12):1511–22.

Wesnes SL, et al. The effect of urinary incontinence status during pregnancy and delivery mode on incontinence postpartum. A cohort study. BJOG. 2009;116(5):700–7.

Gill PNAV. Pelvic Floor and Abdominal Muscle Interaction: EMG Activity and Intra-abdominal Pressure. 2002.

Hodges PW, Sapsford R, Pengel LH. Postural and respiratory functions of the pelvic floor muscles. Neurourol Urodyn. 2007;26(3):362–71.

Park H, Dongwook H. The effect of the correlation between the contraction of the pelvic floor muscles and diaphragmatic. J Phys Ther Sci. 2015;27:2113–5.

Chang SC, et al. Effects of a pushing intervention on pain, fatigue and birthing experiences among Taiwanese women during the second stage of labour. Midwifery. 2011;27(6):825–31.

Başar F. The effect of pushing techniques on duration of the second labor stage, mother and fetus: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Health Services Res Policy. 2018;3(3):123–34.

Buhimschi CS, Buhimschi IA, Malinow AM, Weiner CP. Intrauterine pressure during the second stage of labor in obese women. Am College Obstetrics Gynecol. 2004;103(2):225–30.

Koyucu RG, Demirci N. Effects of pushing techniques during the second stage of labor: A randomized controlled trial. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;56(5):606–12.

Bennett VR, Brown LK. Myles Textbook for Midwives, 13th edition. Churchill Livingstone; 1999.

Cyr MP, et al. Pelvic floor morphometry and function in women with and without puborectalis avulsion in the early postpartum period. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216(3):274.e1–8.

Higgins JPT GS. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. In: Cochrane Book Series. Willey-Blackwell; 2008.

Norris SL, et al. The skills and experience of GRADE methodologists can be assessed with a simple tool. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;79:150–158.e1.

Ahmadi Z, et al. Effect of breathing technique of blowing on the extent of damage to the perineum at the moment of delivery: a randomized clinical trial. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 2017;22(1):62–6.

Bloom SL, et al. A randomized trial of coached versus uncoached maternal pushing during the second stage of labor. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194(1):10–3.

Hansen SL, Clark SL, Foster JC. Active pushing versus passive fetal descent in the second stage of labor: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;99(1):29–34.

Kelly M, et al. Delayed versus immediate pushing in second stage of labor. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. 2010;35(2):81–8.

Low LK, et al. Spontaneous pushing to prevent postpartum urinary incontinence: a randomized, controlled trial. Int Urogynecol J. 2013;24(3):453–60.

Parnell C, et al. Pushing method in the expulsive phase of labor. A randomized trial. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1993;72(1):31–5.

Schaffer JI, et al. A randomized trial of the effects of coached vs uncoached maternal pushing during the second stage of labor on postpartum pelvic floor structure and function. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192(5):1692–6.

Simpson KR, James DC. Effects of immediate versus delayed pushing during second-stage labor on fetal well-being: a randomized clinical trial. Nurs Res. 2005;54(3):149–57.

Thomson AM. Pushing techniques in the second stage of labour. J Adv Nurs. 1993;18(2):171–7.

Yildirim G, Beji NK. Effects of pushing techniques in birth on mother and fetus: a randomized study. Birth. 2008;35(1):25–30.

Fitzpatrick M, et al. A randomised clinical trial comparing the effects of delayed versus immediate pushing with epidural analgesia on mode of delivery and faecal continence. Bjog. 2002;109(12):1359–65.

Fraser WD, et al. Multicenter, randomized, controlled trial of delayed pushing for nulliparous women in the second stage of labor with continuous epidural analgesia. The PEOPLE (Pushing Early or Pushing Late with Epidural) Study Group. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;182(5):1165–72.

Gillesby E, et al. Comparison of delayed versus immediate pushing during second stage of labor for nulliparous women with epidural anesthesia. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2010;39(6):635–44.

Knauth DG, Haloburdo EP. Effect of pushing techniques in birthing chair on length of second stage of labor. Nurs Res. 1986;35(1):49–51.

Plunkett BA, et al. Management of the second stage of labor in nulliparas with continuous epidural analgesia. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102(1):109–14.

Vause S, Congdon HM, Thornton JG. Immediate and delayed pushing in the second stage of labour for nulliparous women with epidural analgesia: a randomised controlled trial. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1998;105(2):186–8.

Tuuli MG, GT, Arya LA, Lowder JL, Woolfolk C, Caughey AB, Srinivas SK, Tina AT, Chhill AG, Richter HE. Impact of second stage pushing timing on maternal pelvic floor morbidity: Multicenter randomized controlled trial. Ajog.org, 2020;56:S6.

Howard D, et al. Differential effects of cough, Valsalva, and continence status on vesical neck movement. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;95(4):535–40.

Chan SSC, et al. Longitudinal pelvic floor biometry: which factors affect it? Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2018;51(2):246–52.

van Veelen A, Schweitzer K, van der Vaart H. Ultrasound assessment of urethral support in women with stress urinary incontinence during and after first pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124(2 Pt 1):249–56.

Tunn R, et al. Pathogenesis of urethral funneling in women with stress urinary incontinence assessed by introital ultrasound. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2005;26(3):287–92.

Thompson JA, et al. Comparison of transperineal and transabdominal ultrasound in the assessment of voluntary pelvic floor muscle contractions and functional manoeuvres in continent and incontinent women. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2007;18(7):779–86.

Gupta JK, et al. Position in the second stage of labour for women without epidural anaesthesia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;5:CD002006.

Lemos A, et al. Pushing/bearing down methods for the second stage of labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;10:Cd009124.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the research assistants and Dr. Edward Barroga for his editing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Katsuko Shinozaki: Project development, Data collection, management and analysis, Manuscript writing

Maiko Suto: Data analysis

Erika Ota: Data analysis and management, Manuscript editing

Hiromi Eto: Data management, Manuscript editing

Shigeko Horiuchi: Manuscript editing, Advice on the project

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest statement

Katsuko Shinozaki (corresponding author) has received research funding from MEXT KAKENHI (grant no. 16K12168).

Maiko Suto declares no conflicts of interest associated with this manuscript.

Erika Ota declares no conflicts of interest associated with this manuscript.

Hiromi Eto declares no conflicts of interest associated with this manuscript.

Shigeko Horiuchi declares no conflicts of interest associated with this manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shinozaki, K., Suto, M., Ota, E. et al. Postpartum urinary incontinence and birth outcomes as a result of the pushing technique: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Urogynecol J 33, 1435–1449 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-021-05058-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-021-05058-5