Abstract

Introduction and hypothesis

We conducted a systematic review of the effectiveness of local preemptive analgesia for postoperative pain control in women undergoing vaginal hysterectomy.

Methods

MEDLINE, EMBASE, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews were searched systematically to identify eligible studies published through September 25, 2019. Only randomized controlled trials and systematic reviews addressing local preemptive analgesia compared to placebo at vaginal hysterectomy were considered. Data were extracted by two independent reviewers. Results were compared, and disagreement was resolved by discussion. Forty-seven studies met inclusion criteria for full-text review. Four RCTs, including a total of 197 patients, and two SRs were included in the review.

Results

Preemptive local analgesia reduced postoperative pain scores up to 6 h and postoperative opioid requirements in the first 24 h after surgery.

Conclusion

Preemptive local analgesia at vaginal hysterectomy results in less postoperative pain and less postoperative opioid consumption.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Hysterectomy for benign indications is one of the most common operations in gynecology. Multiple guidelines and reviews favor the vaginal approach for benign hysterectomy, if feasible [1,2,3,4,5]. In German-speaking countries, vaginal hysterectomy is the most common approach to hysterectomy, with about half of all benign hysterectomies done vaginally [1, 6].

Many Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) protocols in gynecology recommend multimodal analgesia using different agents addressing different pathways to reduce intra- and postoperative opioid requirements, speed recovery and reduce complications [2, 3, 7]. The reduction of opioid requirements is of particular significance considering the potential for misuse of these agents [8,9,10], their side effects and higher costs for the health care system [7]. Recently attempts have been made to improve multimodal perioperative analgesia [8, 9, 11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19]. Due to the opioid crisis, there is high interest in reducing perioperative opioid use. Preemptive analgesia is a part of this concept and denotes all analgesia given before the start of surgery, i.e., before any painful stimulus to the body [20].

We performed this systematic review (SR) because of the clinical relevance of postoperative pain control in a frequently performed procedure.

The primary aim was to systematically review the literature on vaginal hysterectomy with any form of local preemptive analgesia according to postoperative pain reduction. Secondary outcomes were defined as postoperative opioid requirements, readmission rates, perioperative pain management and quality of life measured by validated questionnaires as well as opioid-related side effects.

Materials and methods

The systematic review was restricted to the use of local preemptive analgesia in vaginal hysterectomy; other modes of hysterectomy and other forms of analgesia interventions were excluded. The protocol was registered at PROSPERO and is available under https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42020144709. PRISMA guidelines were followed [21]. No approval was needed from the institutional review board because of the study design.

Data sources and search strategy

Two gynecologists systematically searched MEDLINE (1946 to present), EMBASE (1974 to present), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CCTR) and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR) to identify relevant randomized controlled trials (RCT) and SR. Subject headings and keywords for vaginal hysterectomy were suitably combined with those for local preemptive analgesia or local anesthetics as well as filters for randomized controlled trials or systematic reviews. No restrictions for the date of publication were made, and all full text articles that were published in either English or German were included while those written in other languages were excluded. Reference lists of eligible studies and review articles were included in the search.

Two reviewers (N.T. and A.-M. S.) screened the identified abstracts and removed duplicate entries. Subsequently, all full texts of potentially relevant abstracts were retrieved and screened in the same way. Any discrepancies were resolved by consensus. The screening process and its results were documented in a spreadsheet.

The two reviewers used prespecified extraction templates to independently extract the data. Extracted data included information on the study type and methodology, country/place of the study, inclusion and exclusion criteria, participant demographics, number of participants and measured outcomes and effects. Disagreement was resolved by discussion between the reviewers.

Study selection

The review focused on RCTs and SRs of local preemptive analgesia given prior to vaginal hysterectomy for all indications with the goal of reducing postoperative pain, peri- and postoperative opioid use as well as readmission rates. The search was through 25 September 2019. The intervention had to be compared to another regime or placebo. We excluded laparoscopic or laparoscopically assisted vaginal hysterectomies. For more homogeneous data we also excluded systemic interventions and spinal interventions. Studies including vaginal hysterectomy done for prolapse were included. No restrictions were made on the basis of sample size, country or date of publication.

Data extraction and quality assessment

The quality of the RCTs was assessed with the current version of the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool [22], which comprises domains such as the randomization process, deviations from intended interventions, missing outcome data, measurement of the outcome and selection of the reported result. Because we included only local interventions compared to placebo or no local treatment, we did not need to categorize the different interventions according to their location, but we did categorize them according to their comparison to placebo or no local treatment, participant characteristics and intervention details.

Results

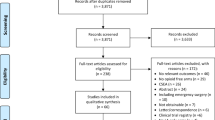

A total of 731 abstracts were identified, and after removal of the duplicates, 539 were screened and 47 full-text manuscripts were selected for further evaluation. As our review focused strictly on preemptive local analgesia in vaginal hysterectomy, we identified 4 RCTs with a total of 197 patients and 2 SRs for inclusion in the SR (Fig. 1). All four RCTs compared local preemptive analgesia with placebo using different local anesthetics.

One study excluded vaginal hysterectomies done for prolapse [23], one study included these procedures [24], one study included only women with prolapse [25], and one is unclear on this question [26].

Applied local anesthetic

Two of the included studies compared 30 ml of 0.5% of ropivacaine vs. placebo [24, 25], and the other two compared 20 ml of 0.5% bupivacaine combined with 1:200,000 epinephrine vs. placebo infiltration [23, 26].

Main outcome

Tables 1 and 2 summarize the significant outcomes and study characteristics of the four studies.

The primary outcomes of all four studies were postoperative pain measured with either the visual analogue scale (VAS) or a verbal analogue pain score from 0 to 10 at different predefined time points between 30 min (min) and 32 h (h) after surgery. Two studies evaluated postoperative pain at rest, one while resting and during coughing and one defining the primary outcome of postoperative pain as pain intensity while coughing.

Both studies which evaluated pain at rest showed a significant reduction in pain for 30 min up to 6 h after surgery. Pain during coughing was also significantly reduced at 1 and 4 h postoperatively in the treatment groups in the two studies that assessed this (Table 2).

Other outcomes

Our predefined secondary outcomes in the four studies included blood loss, length of hospitalization, adverse events, duration of surgery, postoperative nausea and vomiting, and time to first mobilization. These outcomes did not differ between the two groups with or without preemptive analgesia. None of the four RCTs measured quality of life (QoL), readmission rate or perioperative care, so no results to these predefined secondary end points of our protocol can be reported.

None of the four included RCTs reported any adverse events regarding the use of preemptive local anesthesia.

The studies which defined pain at rest or during movement or pain at other evaluated time points as secondary outcomes found also a significant decrease in pain between 1 and 8 h. One secondary outcome all four studies had in common was postoperative morphine consumption. Although the results regarding opioid use in post-anesthesia care were different in two studies, all studies showed a significant reduction in morphine-controlled patient analgesia and/or overall opioid requirements in the treatment group in the first 24 h.

Using the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool [22], we assessed three studies [23,24,25] as having a low risk of bias with clear methods. One of the RCTs [26] lacked specific descriptive statistical analysis and provided no information on confidence intervals used whether mean or median values were reported. This study summarized all pain scores in one figure with only the greatest difference in pain scores appearing after 4 and 6 h. After analyzing the data from the figure, we assumed that the columns showed the mean of the pain scores.

Use of statistics

A meta-analysis was planned but due to the heterogeneity of time points and conditions under which the outcomes were measured, the results of the studies were analyzed descriptively.

Discussion

Our systematic review of preemptive local analgesia at vaginal hysterectomy yielded four RCTs with a total of 197 randomized patients [23,24,25,26]. To our knowledge, this is the first SR of this specific issue.

Main findings

All four RCTs showed a significant decrease in postoperative pain with the use of preemptive analgesia at different measurement points up to 8 h after surgery and a decrease in morphine use over the first 24 h after surgery. However, the effect on postoperative pain reduction is only seen up to 8 h postoperatively, which means that the effect is only measurable on the day of surgery. This is consistent with the half-life of widely used local anesthetic agents. This explains the lack of difference in length of hospital stay [23, 24]. Also, no significant difference was shown in the adverse events of opioid consumption such as nausea, vomiting or sedation [24, 25], which is probably explainable because of the rather small sample size.

Regarding postoperative pain and opioid consumption, the effects were statistically significant and clinically measurable, but the total number of patients investigated was small. However, besides the pain scores reported by Hristovs.ka et al., all postoperative pain score means and medians were under 45 mm on the VAS scale.

There are different VAS cutoffs for mild, moderate and severe pain for the VAS scale ranging from 30, 70 and 100 mm [27] to 44, 74 and 100 mm [28]. Based on guideline recommendations and studies using patient controlled analgesia, a VAS of ≤ 33 mm is considered acceptable pain right after surgery [27]. This means that a great part of the patient population had good postoperative pain control anyway—with or without preemptive analgesia.

Athanasiou et al. [25] studied only patients with prolapse surgery and used combined spinal-epidural block (CSE) instead of general anesthesia. They evaluated two primary end points: postoperative pain scores and the number of patients who had moderate or severe pain, defined as a VAS score ≥ 4 on a 10-cm VAS scale. They showed a significant decrease in the number of patients with higher pain scores up to 8 h after surgery accompanied by significantly less opioid consumption up to 24 h after surgery. The duration of 8 h is explained by the duration of the sensory block of ropivacaine, which is approximately 6–10 h [24, 29]. Although we saw a trend in favor of fewer patients reporting opioid side effects, this was not significant and was likely due to standard use of antiemetics and systemic NSAIDs [25]. For example, Hristovs.ka et al. [24] found that the reduction of postoperative opioid use did not lead to a decline in opioid side effects. Postoperative pain scores were also significantly lower in the treatment group up to 8 h, which is also in line with the 8–13 h duration of bupivacaine [29]. The main difference between this RCT and the other three is that the pain scores in this study were higher than in the others, for reasons which are unclear [24]. The reason for this was not obvious, but because of the similar pain scores of the other three studies with a patient number of 160, assumptions can be made that either there was another surgical approach or the perioperative pain management differed from that of the other studies.

The largest study in this review [23] randomized 90 patients and used 20 ml 0.5% bupivacaine with 1:200,000 epinephrine. They found a decline in pain scores up to 3 h after surgery as well as a reduction in opioid consumption.

The earliest study in our review, published in 2003 [26], has the highest risk of bias indicated by the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool [22]. The pain results are similar to those in the other studies but statistical methods, perioperative analgesia, the anesthetic protocol and results are not described clearly.

There has been much debate about what amount of VAS change is clinically important. A prospective observational study enrolling 224 patients suggested the minimal clinically important difference (MCID) to be 10 in the postoperative setting measured by the VAS scale [27]. However, because of the heterogeneity of surgical procedures, preexisting conditions and individual patients, we have no validated and evidence-based recommendation on the MCID in the postoperative setting [30].

The postoperative pain scores in the present review indicate that patients undergoing vaginal hysterectomy have good postoperative pain control even without preemptive analgesia. With medians and means of 3.1, 4.5, 3.6 and 3.3 points between 3 and 4 h after surgery, most of the patients had postoperative pain scores that can be considered acceptable [27]. Nevertheless, the reported medians and means of 1.3, 1.5, 2.4 and 1.7 of the treatment group were significantly lower, and the suggested MCID of 1 point on the VAS scale was reached in all studies.

All four trials in this review found reduced postoperative opioid requirements during the first 24 h after surgery [23,24,25,26]. Many concepts have been implemented in the last few years to reduce postoperative opioid needs in gynecologic patients, including a shared decision-making model [14], change in discharge regimes in minimal invasive surgeries [13] and a quality improvement intervention protocol [12]. Systemic approaches to multimodal analgesia have included systemic administration of acetaminophen and anti-inflammatory drugs and gabapentin [31,32,33,34,35,36,37]. Our results regarding the benefits of a paracervical block before vaginal hysterectomy are in line with those of the other SRs [35, 38].

Strengths

This is a systematic review of a simple intervention in a frequently performed operation with a clear result. An inexpensive and simple intervention – i.e., preoperative infiltration with a local anesthetic agent, improves patient outcomes.

Limitations

The results of our SR are limited by the studies available. Our review yielded four RCTS with < 200 patients overall. A meta-analysis was not possible because of heterogeneity of end points as well as the use of different local analgesics and the small number of studies included. Also, a sub-analysis according to the indication for vaginal hysterectomy was not possible because of heterogeneity.

Conclusion

The data from four RCTs, with three of them being of good quality, indicate that local preemptive analgesia in the form of a paracervical block is a simple procedure, which results in lower postoperative pain scores and opioid consumption of patients undergoing vaginal hysterectomy. Another systematic review has already described the need for further evidence in minimally invasive hysterectomies [39]. National and international guidelines recommend the vaginal approach [1, 2, 4, 5], and according to fast track pathways [40] and ERAS protocols [3, 7,7,37, 41], multimodal analgesia protocols are recommended to reduce postoperative opioid consumption and improve patient recovery.

Given its easy implementation and low cost, local preemptive analgesia in vaginal hysterectomy is a simple but effective procedure to improve postoperative pain control.

None of these studies used a long-acting, liposomal-bound agent, and this might be a topic for future research. Only one RCT has compared liposomal bupivacaine vs. placebo in posterior vaginal wall surgery and found no significant decrease in postoperative pain or narcotic medication [42].

References

Neis K, Schwerdtfeger K. Indikation und Methodik der Hysterektomie bei benignen Erkrankungen. Published online April 2015. Accessed October 10, 2016. http://www.awmf.org/uploads/tx_szleitlinien/015-070l_S3_Indikation_und_Methodik_der_Hysterektomie_2015-08.pdf

Aarts JW, Nieboer TE, Johnson N, et al. Surgical approach to hysterectomy for benign gynaecological disease. Cochrane Gynaecology and Fertility Group, ed. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. Published online August 12, 2015. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD003677.pub5.

Altman AD, Robert M, Armbrust R, et al. Guidelines for vulvar and vaginal surgery: enhanced recovery after surgery society recommendations. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;223(4):475–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2020.07.039.

Deffieux X, de Rochambeau B, Chene G, et al. Hysterectomy for benign disease: clinical practice guidelines from the French College of Obstetrics and Gynecology. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2016;202:83–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2016.04.006.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Choosing the Route of Hysterectomy for Benign Disease. 2017;(701):5.

Edler K, Tamussino K, Fülöp G, et al. Rates and Routes of Hysterectomy for Benign Indications in Austria 2002–2014. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 2017;77(05):482–6. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0043-107784.

Nelson G, Bakkum-Gamez J, Kalogera E, et al. Guidelines for perioperative care in gynecologic/oncology: enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) society recommendations—2019 update. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2019;29(4):651–68. https://doi.org/10.1136/ijgc-2019-000356.

Horn A, Kaneshiro K, Tsui BCH. Preemptive and preventive pain psychoeducation and its potential application as a multimodal perioperative pain control option: a systematic review. Anesth Analg. 2020;130(3):559–73. https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000004319.

Kamel MK. Commentary: role of pre-emptive analgesia in reversing the opioid epidemic. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2020;159(2):745–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtcvs.2019.10.181.

Simpson J, Bao X, Agarwala A. Pain Management in Enhanced Recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocols. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2019;32(02):121–8. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0038-1676477.

Petrikovets A, Sheyn D, Sun HH, et al. Multimodal opioid-sparing postoperative pain regimen compared with the standard postoperative pain regimen in vaginal pelvic reconstructive surgery: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;221(5):511.e1–511.e10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2019.06.002.

Margolis B, Andriani L, Baumann K, Hirsch AM, Pothuri B. Safety and feasibility of discharge without an opioid prescription for patients undergoing gynecologic surgery. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;136(6):1126–34. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000004158.

Mark J, Argentieri DM, Gutierrez CA, et al. Ultrarestrictive Opioid Prescription Protocol for Pain Management After Gynecologic and Abdominal Surgery. Obstet Gynecol. Published online December 2018:14.

Vilkins AL, Sahara M, Till SR, et al. Effects of shared decision making on opioid prescribing after hysterectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;134(4):823–33. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000003468.

Trabulsi EJ, Patel J, Viscusi ER, Gomella LG, Lallas CD. Preemptive multimodal pain regimen reduces opioid analgesia for patients undergoing robotic-assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy. Urology. 2010;76(5):1122–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2010.03.052.

Solouki S, Plummer M, Agalliu I, Abraham N. Opioid prescribing practices and medication use following urogynecological surgery. Neurourol Urodyn. 2019;38(1):363–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/nau.23867.

Movilla PR, Kokroko JA, Kotlyar AG, Rowen TS. Postoperative opioid use using enhanced recovery after surgery guidelines for benign gynecologic procedures. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2020;27(2):510–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmig.2019.04.017.

Clavé H, Clavé A. Safety and efficacy of advanced bipolar vessel sealing in vaginal hysterectomy: 1000 cases. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2017;24(2):272–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmig.2016.10.017.

Zakaria MA, Levy BS. Outpatient vaginal hysterectomy: optimizing perioperative Management for Same-day Discharge. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120(6):1355–61. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182732ece.

Preemptive analgesia for postoperative hysterectomy pain control: systematic review and clinical practice guidelines. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217(3):303–313.e6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2017.03.013

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. https://journals.plos.org/plosmedicine/. Published July 2009. Accessed December 15, 2020. https://journals.plos.org/plosmedicine/article?id=10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2019;366. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l4898.

Long JB, Eiland RJ, Hentz JG, et al. Randomized trial of preemptive local analgesia in vaginal surgery. Int Urogynecology J. 2009;20(1):5–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-008-0716-6.

Hristovs.ka A-M, Kristensen BB, Rasmussen MA, et al. Effect of systematic local infiltration analgesia on postoperative pain in vaginal hysterectomy: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2014;93(3):233–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/aogs.12319.

Athanasiou S, Hadzillia S, Pitsouni E, et al. Intraoperative local infiltration with ropivacaine 0.5% in women undergoing vaginal hysterectomy and pelvic floor repair: Randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2019;236:154–159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2019.03.016

O’Neal MG, Beste T, Shackelford DP. Utility of preemptive local analgesia in vaginal hysterectomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189(6):1539–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2003.10.691.

Myles PS, Myles DB, Galagher W, et al. Measuring acute postoperative pain using the visual analog scale: the minimal clinically important difference and patient acceptable symptom state. Br J Anaesth. 2017;118(3):424–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/bja/aew466.

Hawker GA, Mian S, Kendzerska T, French M. Measures of adult pain: visual analog scale for pain (VAS pain), numeric rating scale for pain (NRS pain), McGill pain questionnaire (MPQ), short-form McGill pain questionnaire (SF-MPQ), chronic pain grade scale (CPGS), short Form-36 bodily pain scale SF. Arthritis Care Res 2011;63(S11):S240-S252. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.20543.

Venkatesh RR. A Randomized Controlled Study of 0.5% Bupivacaine, 0.5% Ropivacaine and 0.75% Ropivacaine for Supraclavicular Brachial Plexus Block. J Clin Diagn Res. Published online 2016. https://doi.org/10.7860/JCDR/2016/22672.9021

Muñoz-Leyva F, El-Boghdadly K, Chan V. Is the minimal clinically important difference (MCID) in acute pain a good measure of analgesic efficacy in regional anesthesia? Reg Anesth Pain Med. Published online September 7, 2020:rapm-2020-101670. https://doi.org/10.1136/rapm-2020-101670

Reagan KML, O’Sullivan DM, Gannon R, Steinberg AC. Decreasing postoperative narcotics in reconstructive pelvic surgery: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217(3):325.e1–325.e10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2017.05.041

Doleman B, Heinink TP, Read DJ, Faleiro RJ, Lund JN, Williams JP. A systematic review and meta-regression analysis of prophylactic gabapentin for postoperative pain. Published online 2015:19.

Weingarten TN, Jacob AK, Njathi CW, Wilson GA, Sprung J. Multimodal analgesic protocol and Postanesthesia respiratory depression during phase I recovery after Total joint arthroplasty. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2015;40(4):7.

Ong CK, Lirk P, Seymour RA, Jenkins BJ. The efficacy of preemptive analgesia for acute postoperative pain management: a meta-analysis. PubMed Health. Published online 2005. Accessed September 1, 2018. https://www-1ncbi-1nlm-1nih-1gov-10013b5051bf4.han.medunigraz.at/pubmedhealth/PMH0022330/

Long JB, Bevil K, Giles DL. Preemptive analgesia in minimally invasive gynecologic surgery. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2019;26(2):198–218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmig.2018.07.018.

Ramaseshan AS, David M. O’Sullivan, Adam C. Steinberg,, Elena Tunitsky-Bitton. A comprehensive model for pain management in patients undergoing pelvic reconstructive surgery: a prospective clinical practice study. Published online 2020:8.

Cain KE, Iniesta MD, Fellman BM, et al. Effect of preoperative intravenous vs. oral acetaminophen on postoperative opioid consumption in an enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) program in patients undergoing open gynecologic oncology surgery. Gynecol Oncol Published online December 6, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2020.11.024.

Blanton E, Lamvu G, Patanwala I, et al. Non-opioid pain management in benign minimally invasive hysterectomy: a systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216(6):557–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2016.12.175.

Steinberg AC, Schimpf MO, White AB, et al. Preemptive analgesia for postoperative hysterectomy pain control: systematic review and clinical practice guidelines. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217(3):303–313.e6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2017.03.013

Ottesen M, Sørensen M, Rasmussen Y, Smidt-Jensen S, Kehlet H, Ottesen B. Fast track vaginal surgery. Published online 2002:9.

Miralpeix E, Nick AM, Meyer LA, et al. A call for new standard of care in perioperative gynecologic oncology practice: impact of enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) programs. Gynecol Oncol. 2016;141(2):371–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2016.02.019.

Jones CL, Gruber DD, Fischer JR, Leonard K, Hernandez SL. Liposomal bupivacaine efficacy for postoperative pain following posterior vaginal surgery: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;219(5):500.e1–500.e8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2018.09.029

Funding

Open access funding provided by Medical University of Graz.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N. Taumberger: protocol/project development, manuscript writing/editing.

A.-M. Schütz: protocol/project development, manuscript writing/editing.

K. Jeitler: data collection and management, data analysis.

Andrea Siebenhofer: data collection and management, data analysis.

H. Simonis: protocol/project development, manuscript editing.

Helmar Bornemann-Cimenti: protocol/project development, manuscript editing.

R. Laky: protocol/project development, manuscript editing.

K. Tamussino: protocol/project development, manuscript writing/editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

None.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Taumberger, N., Schütz, AM., Jeitler, K. et al. Preemptive local analgesia at vaginal hysterectomy: a systematic review. Int Urogynecol J 33, 2357–2366 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-021-04999-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-021-04999-1