Abstract

Introduction and hypothesis

Although the main function of the suspensory ligaments of the vaginal apex is to prevent its descent toward the vaginal introitus, there remains limited information regarding its normal physiological motion. This study was aimed at quantifying the motion of the non-prolapsed vaginal apex during strain and defecation maneuvers.

Methods

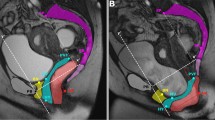

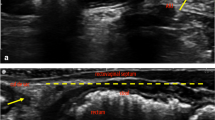

This study represents a sub-analysis of a parent study that was aimed at evaluating rectal mobility with regard to obstructed defecation symptoms. Patients with normal apical vaginal support who had undergone MR defecography were entered into the study. For each patient, midsagittal images at rest, maximum strain, and maximum evacuation were utilized. The location of the cervicovaginal junction, S4–S5 intervertebral disc, sacral promontory, and hymen were identified. Vectors were calculated from each of these landmarks to the vaginal apex to compare vector angles and magnitudes across subjects.

Results

Twelve patients were included in this study. At rest, the vagina extends from the hymen, which is inferior and posterior to the inferior symphysis pubis, to the vaginal apex at an angle of 45.2° ± 14.5° relative to the pubococcygeal line. This angle became more acute with strain and even more so during maximum evacuation (14.1° ± 9.0°, p < 0.001). Differences in the vector magnitude, although not statistically significant, showed a trend indicating shorter lengths with maximum evacuation.

Conclusions

The vaginal apex is a highly mobile structure demonstrating significantly more mobility during defecation compared with strain. The data obtained contradict the general perception that the vaginal apex is relatively fixed within the pelvis of normally supported women.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Blaisdell FE Sr. The anatomy of the sacro-uterine ligaments. Anat Rec. 1917;12(1):1–42.

Range RL, Woodburne RT. The gross and microscopic anatomy of the transverse cervical ligament. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1964;90(4):460–7.

Chen L, Ramanah R, Hsu Y, Ashton-Miller JA, DeLancey JO. Cardinal and deep uterosacral ligament lines of action: MRI based 3D technique development and preliminary findings in normal women. Int Urogynecol J. 2013;24(1):37–45.

DeLancey JO. Surgery for cystocele III: do all cystoceles involve apical descent? Int Urogynecol J. 2012;23(6):665–7.

Kantartzis KL, Turner LC, Shepherd JP, Wang L, Winger DG, Lowder JL. Apical support at the time of hysterectomy for uterovaginal prolapse. Int Urogynecol J. 2015;26(2):207–12.

Swenson CW, Luo J, Chen L, Ashton-Miller JA, DeLancey JO. Traction force needed to reproduce physiologically observed uterine movement: technique development, feasibility assessment, and preliminary findings. Int Urogynecol J. 2016;27(8):1227–34.

Schreyer AG, Paetzel C, Fürst A, Dendl LM, Hutzel E, Müller-Wille R, et al. Dynamic magnetic resonance defecography in 10 asymptomatic volunteers. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18(46):6836.

Nygaard IE, McCreery R, Brubaker L, Connolly A, Cundiff G, Weber AM, et al. Abdominal sacrocolpopexy: a comprehensive review. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104(4):805–23.

Halaska M, Maxova K, Sottner O, Svabik K, Mlcoch M, Kolarik D, et al. A multicenter, randomized, prospective, controlled study comparing sacrospinous fixation and transvaginal mesh in the treatment of posthysterectomy vaginal vault prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;207(4):301.e1–7.

Barone WR, Moalli PA, Abramowitch SD. Textile properties of synthetic prolapse mesh in response to uniaxial loading. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215(3):326.e1–9.

Broekhuis SR, Fütterer JJ, Barentsz JO, Vierhout ME, Kluivers KB. A systematic review of clinical studies on dynamic magnetic resonance imaging of pelvic organ prolapse: the use of reference lines and anatomical landmarks. Int Urogynecol J. 2009;20(6):721–9.

Cates J, Fletcher T, Whitaker R. A hypothesis testing framework for high-dimensional shape models. In: 2nd MICCAI workshop on mathematical foundations of computational anatomy; 2008. p. 170–81.

Baessler K, Schuessler B. Abdominal sacrocolpopexy and anatomy and function of the posterior compartment. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;97(5):678–84.

Maher CF, Qatawneh AM, Dwyer PL, Carey MP, Cornish A, Schluter PJ. Abdominal sacral colpopexy or vaginal sacrospinous colpopexy for vaginal vault prolapse: a prospective randomized study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190(1):20–6.

Pilsgaard K, Mouritsen L. Follow-up after repair of vaginal vault prolapse with abdominal colposacropexy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1999;78(1):66–70.

Virtanen H, Hirvonen T, Mäkinen J, Kiilholma P. Outcome of thirty patients who underwent repair of posthysterectomy prolapse of the vaginal vault with abdominal sacral colpopexy. J Am Coll Surg. 1994;178(3):283–7.

Geomini PM, Brölmann HA, van Binsbergen NJ, Mol BW. Vaginal vault suspension by abdominal sacral colpopexy for prolapse: a follow up study of 40 patients. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2001;94(2):234–8.

Sung VW, Rogers RG, Schaffer JI, Balk EM, Uhlig K, Lau J, et al. Graft use in transvaginal pelvic organ prolapse repair: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(5):1131–42.

Stanford E, Cassidenti A, Moen M. Traditional native tissue versus mesh-augmented pelvic organ prolapse repairs: providing an accurate interpretation of current literature. Int Urogynecol J. 2012;23(1):19–28.

Ow LL, Lim YN, Dwyer PL, Karmakar D, Murray C, Thomas E, et al. Native tissue repair or transvaginal mesh for recurrent vaginal prolapse: what are the long-term outcomes? Int Urogynecol J. 2016;27(9):1313–20.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

None.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rostaminia, G., Routzong, M., Chang, C. et al. Motion of the vaginal apex during strain and defecation. Int Urogynecol J 31, 391–400 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-019-03981-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-019-03981-2