Abstract

Long wave chronologies are generally established by identifying phase periods associated with relatively higher and lower average growth rates in the world economy. However, the long recognition lag typical of the phase-growth approach prevents it from providing timely information about the present long wave phase period. In this paper, using world GDP growth rates data over the period 1871–2016, we develop a system for long wave phases dating, based on the systematic timing relationship between cyclical representations in growth rates and in levels. The proposed methodology allows an objective periodization of long waves which is much more timely than that based on the phase-growth approach. We find a striking concordance of the established long waves chronology with the dating chronologies elaborated by long wave scholars using the phase-growth approach, both in terms of the number of high- and low-growth phases of the world economy and their approximate time of occurrence. In terms of the current long wave debate, our findings suggest that the upswing phase of the current fifth long wave is still ongoing, and thus the recent financial/economic crisis only marks a flattening in the current upswing phase of the world economy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

See, for example, the popular book recently published by the Marxist economist Paul Mason (2015) on post-capitalism which has brought long wave thinking into a much wider audience than the typical specialist academic audience.

The term techno-economic paradigm instead of “technological paradigm” (Dosi 1982) reflects the idea that such changes do not merely involve engineering trajectories for specific products or process technologies.

The most important novel feature of the MLP is that a transition of a socio-technical system stems from the interaction of events in its basic components, that is, (innovation) niches, socio-technical regimes, and landscapes (Grin et al. 2010).

The transition to a new techno-economic regime is a period of structural change in which the process of transformation in the economy cannot proceed smoothly, not only because it implies massive transformation and much destruction of existing plant, but mainly because the prevailing pattern of social behavior and the existing institutional structure are shaped around the requirements and possibilities created by the previous paradigm (Perez 2002).

Price series have been for a long time the only economic data available and consistently measured. Indeed, annual data on price indexes go back to late eighteenth century, allowing researchers to use the longest possible time span as well as a number of observations greater than any corresponding international dataset. By contrast, output variables have been reconstructed by economic historians relatively recently and mostly back to the mid-nineteenth century.

The data source is the Maddison Project Database, version 2018 (Bolt et al. 2018). World GDP before 1950 is computed by summing real GDP across different subsets of countries (each country’s real GDP is preliminarily obtained by multiplying real GDP per capita in 2011$ by population in mid-year thousands). The country coverage before 1950 changes as follows: 1850- (Australia, Belgium, Chile, Denmark, France, Germany, Great Britain, Greece, Indonesia, Italy, Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, US), 1870- (Finland, Canada, New Zealand, Japan, Brazil, Uruguay, Venezuela, Sri Lanka), 1884- (India), 1900- (Argentina, Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, Mexico and Per√π), 1902 (Cuba, Philippines), 1906- (Panama), 1920- (Costa Rica, Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador, Nicaragua, Ireland, Romania, Former USSR), 1923- (Turkey). Country coverage, in terms of World GDP, goes from 62% in 1870 to 78% in 1929. After 1950 regional data for the World aggregate are used. All data are available at www.ggdc.net/maddison.

For example, between the late 18th and early 20th centuries the level of wholesale prices tends to display a very large amount of variation over time around a trendless or slightly declining trend, whereas after WWII, prices start increasing as a consequence of a change in the process of price determination (van Ewijk 1982), the effect being the emergence of a strong positive trend (Gallegati et al. 2017).

These filters are derived by approximating the frequency domain properties of the ideal band-pass filter. Since the exact band-pass filter is a moving average of infinite order, a finite order approximation is necessary in practical applications.

The ideal band-pass filter can be better approximated with the longer moving averages. Using a larger number of leads and lags allows for a better approximation of the exact band-pass filter, but makes unusable more observations at the beginning and end of the sample.

Wavelets, their generation and their potential usefulness are discussed in intuitive terms in Ramsey (2010, 2014). A more technical exposition with many examples of the use of wavelets in a variety of fields is provided by Percival and Walden (2000), while excellent introductions to wavelet analysis with many interesting economic and financial examples are given in Gencay et al. (2002) and Crowley (2007).

Since the data need not be detrended nor are corrections for war years needed anymore, with wavelet analysis we can avoid the practice of studying history by erasing part of the history (Freeman and Louca 2001).

The mother wavelet plays a role similar to sines and cosines in the Fourier decomposition. They are compressed or dilated, in the time domain, to generate cycles to fit actual data.

For the DWT, where the number of observations is N = 2J, the number of coefficients at each dyadic scale is: N=N/2J + N/2J + N/2J-1 + ... + N/4 + N/2, that is, there are N/2J coefficients sJ,k, N/2J coefficients dJ,k, N/2J-1 coefficients dJ-1,k ... and N/2 coefficients d1,k.

The two phases are generally called Phase A and Phase B in the long waves literature.

Step cycles, first analyzed by Friedman and Schwartz (1963) in their work on money, were initially proposed with deviation cycles to identify growth cycles.

The letters refer to the sequence of turning points for different classification of business cycles: α and β are peaks and troughs for growth rate cycles, B and C peaks and trough for classical cycles, A and D peaks and troughs for growth cycles.

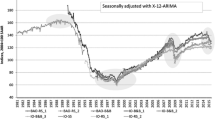

The application of the MODWT with a number of levels J = 5 with annual time series produces five wavelet details vectors D1, D2, D3, D4 and D5 which correspond to fluctuations between 2 and 4, 4–8, 8–16, 16–32 and 32–64 years, respectively. Wavelet decomposition analysis was carried out with R package waveslim from B. Whitcher.

The first wave (steam engine) and the upswing of the second wave cover the first half of the nineteenth century and thus are excluded from our sample.

According to the paradigm of technological innovation, there are two periods within an innovation paradigm with the diffusion of innovation preceded by a technological development period occurring during the downswing phase of a long wave.

A complete list of existing long wave chronologies may be found in Bosserelle (2012).

Maddison employs several macroeconomic indicators, namely the rate of growth of the volume of output, the output per head and exports, the cyclical variations in output and exports, unemployment, and the rate of change in consumer prices.

That the end of the fourth wave did not expire in the 1990s is also argued by Mason (2015), although in his view the downturn of the fourth wave prolonged until 2008.

Before WWI Maddison’s dating fails to detect a phase change in the early 1890s probably because his methodology aims at identifying major changes in growth momentum.

Goldstein (1999, p.90) signals “as a source of potential difficulty for estimating long cycles the interaction between the impact of WWI and the rapid expansion of the 1920s”. Over the 1920s the US experienced an unprecedented period of sustained industrial and economic growth based on the implementation of standardized mass-production in industry and large-scale diffusion and use of new products such as the automobile, household appliances, and other mass-produced products (the US average annual growth rate of real GNP over the 1920–29 period equal to 4.6%). Moreover, over the same period, the relative international economic strength of the US economy increased considerably, both in terms of world industrial output and the share of the world market, at the expense of the European countries, the manufacturing industries, transport system and agricultural land of which had been greatly damaged during WWI.

We thank one of the two anonymous referees for suggesting these specific robustness checks. Wavelet estimated variables are presented in the middle and bottom panels of Figure 4.

Before 1950 real GDP per-capita is computed by summing real GDP across countries and dividing by population.

References

Allianz Global Investors (2010) Analysis and trends: the sixth Kondratieff-long waves of prosperity. Allianz Global Investors, Frankfurt

Anas J, Ferrara L (2004) Detecting cyclical. Turning Points: The ABCD Approach and Two Probabilistic Indicators. J Bus Cycle Meas Anal 12(2):193–225

Anas J, Billio M, Ferrara L, Mazzi GL (2008) A system for dating and detecting turning points in the euro area. Manch Sch 76(5):549–577

Baxter M (1994) Real exchange rates and real interest differentials. Have We Missed the Business-Cycle Relationship? J Mon Econ 33:5 37

Baxter M, King R (1999) Measuring business Cycles: approximate band-pass Filters for economic time series. Rev Econ Stat 81:575–593

Becker R, Enders W, Lee J (2006) A stationary test with an unknown number of smooth breaks. J Time Ser Anal 27:381–409

Bernard L, Gevorkyan A, Palley T, Semmler W (2014) Time scales and mechanisms of economic cycles: a review of theories of long waves. Review of Keynesian Economics 2(1):87–107

Berry BJL (1991) Introduction in long wave rhythms in economic development and political behavior. John Hopkins University Press, Baltimore

Bolt J, Inklaar R, de Jong H, van Zanden JL (2018) Rebasing, Maddison: new income comparisons and the shape of long-run economic development. Maddison Project Working Paper n:10

E Bosserelle (2012) La croissance economique dans le long terme: S. Kuznets versus N.D. Kondratiev - Actualité d'une controverse apparue dans l’entre-deux-guerres. Economies et Societes, Cahiers de l'ISMEA, serie Histoire economique quantitative, AF, 45 1655‑1688

Chase-Dunn C, Grimes P (1995) World-systems analysis. Annu Rev Sociol 21:387 417

Christiano LJ, Fitzgerald TJ (2003) The band pass filter. Intern Econ Rev 44(2):435–465

Crowley P (2007) A guide to wavelets for economists. J Econ Surv 21:207–267

Daubechies I (1992) Ten lectures on wavelets, CBSM-NSF regional conference series in applied mathematics, vol 61. SIAM, Philadelphia

Devezas TC, Corradine JT (2001) The biological determinants of long-wave behaviour in socioeconomic growth and development. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 68(1):57

Devezas TC (2010) Crises, depressions, and expansions: global analysis and secular trends. Technol Forecast Soc Change 77:739 761

Dosi G (1982) Technological paradigms and technological trajectories. Res Policy 11:147 162

van Duijn JJ (1983) The long wave in economic life. Allen and Unwin, Boston, MA

Enders W, Lee J (2009) A unit root test using a Fourier series to approximate smooth breaks. Oxf Bull Econ Stat

Erten B, Ocampo JA (2013) Super cycles of commodity prices since the mid nineteenth century. World Devel 44:14 30

Everts M, Filters B-P (2006) Munich Personal RePec Archive Paper no 2049

van Ewijk C (1982) A spectral analysis of the Kondratieff cycle. Kyklos 35(3):468 499

Freeman C (1983) Long waves in the world economy. Frances Pinter, London

Freeman C (2009) Techno-economic paradigms. Essays in honour of Carlota Perez. In: Drechsler W, Kattel R, Reinert ES (eds) Schumpeter’s business Cycles and techno-economic paradigms. Anthem Press, London

Freeman C, Perez C (1988) In: Dosi G, Freeman C, Nelson R, Silverberg G, Soete L (eds) Technical Change and Economic TheoryStructural crises of adjustment: business Cycles and investment behaviour. Pinter Publisher, London

Freeman C, Louca F (2001) As time Goes by: from the industrial revolutions to the information revolution. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Friedman M, Schwartz AJ (1963) A monetary history of the United States. NBER Publications. Princeton University Press, Princeton, pp 1867–1960

Gallant AR (1981) On the bias in flexible functional forms and an essentially unbiased form. the flexible Fourier form J Econom 15:211 245

Gallegati M, Gallegati M, Ramsey JB, Semmler W (2017) Long waves in prices: new evidence from wavelet analysis. Cliometrica 11(1):127 151

Marco Gallegati D (2018) Delli Gatti, long waves in history: a new global financial instability index. J Econ Dynam Control, 91 190:205

Geels FW (2002) Technological transitions as evolutionary reconfiguration processes: a multilevel perspective and a case-study. Res Policy 31(8):1257–1274

Geels FW, Kemp R, Dudley G, Lyons G (eds) (2012) Automobility in transition? A Socio-Technical Analysis of Sustainable Transport. Routledge, New York

Gencay R, Selcuk F, Whitcher B (2002) An introduction to wavelets and other filtering methods in finance and Economics. San Diego Academic Press, San Diego

Goldstein JS (1988) Long Cycles: prosperity and war in the modern age. Yale University Press, New Haven

Goldstein JP (1999) The existence, endogeneity and synchronization of long waves: structural time series model estimates. Rev Radic Polit Econ 31:61 101

Gordon DM (1978) Up and down the long roller coaster? In: Economics P (ed) Union for Radical. U.S. Capitalism in Crisis, URPE, New York

Gore C (2010) The global recession of 2009 in a long-term development perspective. J Intern Dev 22(6):714–738

Grin J, Rotmans J, Schot J (2010) Transitions to sustainable development: new directions in the study of long term transformative change. Routledge, New York

Hamilton JD (1989) A new approach to the economic analysis of nonstationary time series and the business cycle. Econom. 57:357 384

Harding D, Pagan A (2016) The econometric analysis of recurrent events in macroeconomics and finance. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Heap A (2005) China - the engine of a commodities super cycle. Citigroup Smith Barney, New York City

Jerret D, Cuddington JT (2008) Broadening the statistical search for metal Price super Cycles to steel and related metals. Res Policy 33:188 195

Kleinknecht A (1981) Innovation, accumulation, and crisis: waves in economic development. Review (Fernand Braudel Center) IV 687 711

Kohler J (2012) A comparison of the neo-Schumpeterian theory of Kondratiev waves and the multi-level perspective on transitions. Environ Innov Soc Transit 3:1–15

Kondratiev ND (1935) The long waves in economic life. Rev Econ Stat 17(6):105–115

Korotayev AV, Tsirel SV (2010) A spectral analysis of world GDP dynamics: Kondratieff waves, Kuznets swings, Juglar and Kitchin Cycles in global economic development, and the 2008-2009 economic crisis. Struct Dyn 4(1):3–57

Kriedel N (2009) Long waves of economic development and the diffusion of general-purpose technologies: the case of railway networks. Economies et Societes, serie histoire economique quantitative. AF, 40 877:900

Kuczynski T (1978) Spectral analysis and cluster analysis as mathematical methods for the periodization of historical processes. Kondratieff Cycles - appearance or reality? In: Proceedings of the seventh international economic history congress, vol 2. International Economic History Congress, Edinburgh, pp 79–86

Kuczynski T (1982) Leads and lags in an escalation model of capitalist development: Kondratieff Cycles reconsidered, proceedings of the eighth international economic history congress. Vol. 3. International economic history congress. Budapest

Lewis WA (1978) Growth and fluctuations 1870–1913. Allen and Unwin, MA

Maddison A (1991) Dynamic forces in capitalist development. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Maddison A (2003) The world economy: historical statistics. OECD, Paris

Maddison A (2007) Fluctuations in the momentum of growth within the capitalist epoch. Cliometrica 1:145 175

Mason P (2015) PostCapitalism: A Guide to our Future. Allen Lane, UK

Metz R (1992) A re-examination of long waves in aggregate production series. In: Kleinknecht A (ed) New findings in long waves research. St. Martin’s Printing, New York

Mintz I (1969) Dating Postwar Business Cycles: Methods and their application to Western Germany: 1950-1967. In: Occasional Paper, vol 107. NBER, New York

Mintz I (1972) Dating American growth Cycles. In: Zarnowitz V (ed) The business cycle today. NBER, New York

Percival DB, Walden AT (2000) Wavelet methods for time series analysis. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Perez C (2002) Technological revolutions and financial capital: the dynamics of bubbles and Golden ages. Edward Elgar, UK, Cheltenham

Perez C (2007) Finance and technical change: a long-term view. In: Hanusch H, Pyka A (eds) The Elgar companion to neo-Schumpeterian Economics. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham

Perez C (2009) The double bubble at the turn of the century: technological roots and structural implications. Camb J Econ 33(4):779–805

Perez C (2010) Technological revolutions and techno-economic paradigms. Camb J Econ 34:185 202

Proietti T (2011) Trend estimation. In: Lovric M (ed) International encyclopedia of statistical science, 1st edn. Springer, Berlin

Ramsey JB (2010) Wavelets. In: Durlauf SN, Blume LE (eds) The new Palgrave dictionary of Economics. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke

Ramsey JB (2014) Functional representation, approximation, bases and wavelets. In: Gallegati M, Semmler W (eds) Wavelet applications in Economics and finance. Springer-Verlag, Heidelberg

Ramsey JB, Zhang Z (1996) The application of waveform dictionaries to stock market index data. In: Kravtsov YA, Kadtke J (eds) Predictability of complex dynamical systems. Springer-Verlag, Berlin

Reati A, Toporowski J (2009) An economic policy for the fifth long wave. PSL quart. Rev, 62 143:186

Rosenberg N, Frischtak CR (1983) Long waves and economic growth: a critical appraisal. Amer Econ Rev 73:146–151

Schot J, Kanger L (2018) Deep transitions: emergence, acceleration, stabilization and directionality. Res Policy 47(6):1045 1059

Schot J (2016) Confronting the second deep transition through the historical imagination. Technol Cult 57(2):445–456

Schumpeter JA (1939) Business Cycles. McGraw-Hill, New York, NY

Standard Chartered, The super-cycle report. London: global research standard Chartered, 2010

Swilling M (2013) Economic Crisis, Long Waves and the sustainability transition: an African perspective. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 6:96–115

Terasvirta T (1994) Specification, estimation, and evaluation of smooth transition autoregressive models. J Amer Stat Ass 89:208 218

Tyfield D (2016) On Paul Mason’s “post-capitalism”: an extended review. Mimeo

Tylecote A (1991) The long wave in the world economy. Routledge, London

Vogelsang TJ, Perron P (1998) Additional tests for a unit root allowing for a break in the trend function at an unknown time. Intern. Econ. Rev. 39:1073 1100

Acknowledgements

I’d like to thank two anonymous referees that with their comments contributed to greatly improve the paper. All errors and responsibilities are, of course, mine.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(CSV 24 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gallegati, M. A system for dating long wave phases in economic development. J Evol Econ 29, 803–822 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00191-019-00622-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00191-019-00622-1