Abstract

Ever since an “evolutionary” perspective on the economy has been suggested, there have been differing, and partly incommensurable, views on what specifically this means. By working out where the differences lie and what motivates them, this paper identifies four major approaches to evolutionary economics. The differences between them can be traced back to opposite positions regarding the basic assumptions about reality and the proper conceptualization of evolution. The same differences can also be found in evolutionary game theory. Achievements of the major approaches to evolutionary economics and their prospects for future research are assessed by means of a peer survey.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

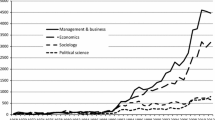

The question of what is specific about an evolutionary approach to economics has been discussed ever since the label “evolutionary” was introduced into an economic context in the late 19th century. A commonly accepted answer is still pending. Nevertheless, interest in applying evolutionary thought to economics has increased in recent years. In their bibliometric analysis of the EconLit database, Silva and Teixeira (2006) find that the number of articles published in economic journals using the term “evolutionary” as a keyword grew roughly exponentially between 1986 and 2005. In 2005, such articles were about 1% of all journal publications covered by EconLit in that year. However, Silva and Teixeira also find that the increasing use of the term does not correspond with anything like growing coherence in what it is supposed to refer to. There is still no agreement about the specific features associated with the label “evolutionary” in economic analysis, not to speak of a commonly accepted paradigmatic “hard core” like, e.g., the equilibrium-cum- optimization framework in canonical economic theory.

Under these conditions it seems desirable to reflect on the differences in interpretations, topics, and methods in evolutionary economics and on their reasons—not least in order to explore the chances for reconciling the different positions. This is particularly warranted in view of some recent developments in the field. On the one hand, there is an ongoing interest in the role played by evolutionary biology and Darwinism in evolutionary economics (see, e.g., Nelson 1995; Foster 1997; Witt 1999; Laurent and Nightingale 2001; Knudsen 2002; Andersen 2004)—an interest driven by the search for a unified evolutionary approach. On the other hand, there are signs of disintegration. Evolutionary game theory, for instance, takes little notice of the research that is more broadly associated with evolutionary economics and vice versa (see, e.g., Samuelson 2002 on the one side and Nelson and Winter 2002 on the other). An attempt will therefore be made in this paper to identify the main sources of disagreement on what is meant by the label “evolutionary” in the economic context. In this attempt, the prospects for, or the limits of, a unified evolutionary approach should become apparent. Such a clarification should also benefit the assessment of the new developments in the field.

Scientific approaches can differ in many respects. The most consequential differences usually occur at three levels of scientific reasoning. These are the ontological level (what basic assumptions are made about the structure of reality), the heuristic level (how the problems are framed to induce hypotheses), and the methodological level (what methods are used to express and verify theories). A key to a better understanding of evolutionary economics, it will be argued, is to distinguish between these three levels and the corresponding, often only implicit, assumptions. What different authors consider special about the evolutionary approach, for instance, is likely to depend on how they conceptualize “evolution” in the economic context. This is a decision at the heuristic level, i.e. about what concepts to use to frame problems and their interpretations. A different issue is how the authors define the agenda of evolutionary economics. Economic phenomena can be seen as forming an own sphere of reality, e.g., a sphere of subjective likings and beliefs. The agenda then differs from the one that results when economic activities are seen, e.g., in a Darwinian world view, that is, as an interaction with nature’s constraints and contingent on the human genetic endowment. This is a decision at the ontological level where the assumptions about the structure of reality shape the perception of objects and disciplinary boundaries (see Dopfer 2005).

In many neo-Schumpeterian contributions to evolutionary economics, metaphors based on analogies to the Darwinian theory of natural selection are strongly endorsed at the heuristic level (i.e. as a means of conceptualizing evolution in the economic domain). At the same time, the challenge of a naturalistic, Darwinian world view on the economy is usually ignored, if not rejected, at the ontological level. Conversely, authors like Veblen (1898), Georgescu-Roegen (1971), Hayek (1988), and North (2005) who have adopted a naturalistic approach to evolutionary economics—but differ widely in most other respects—do not work with analogies to Darwinian concepts at the heuristic level. In contrast, the new approach of Universal Darwinism advocates just such a combination of a heuristic based on an abstract analogy to Darwinian concepts and a naturalistic ontological position (Hodgson 2002; Hodgson and Knudsen 2006). Evolutionary game theory basically ignores the conceptual debates and controversies in evolutionary economics. Yet, as will be explained, within evolutionary game theory the opinions are divided exactly along the same lines.

Finally, there is a third, the methodological, level where controversial assumptions can be made. Here, a truly enduring controversy relates to the question of whether and how to account for the role of history in economic theorizing. As will turn out, however, this question is much less controversial in evolutionary economics, probably because, in all of its different interpretations, the historical contingency of evolutionary processes is clearly acknowledged. Different positions at the methodological level therefore usually mean that they suggest different methods for coming to grips with the historical dimension. However, in most cases the choice of the method is determined by the particularities of the problems investigated. Often the methods are complementary rather than alternatives. The decisions at the methodological level are therefore more a matter of pragmatics than principles and not the reason for the differences in the views about what is specific about evolutionary economics.

In this paper it will therefore be argued that differing interpretations of evolutionary economics have their origin in the, often not explicitly stated, divergent ontological and heuristic positions. To elaborate on this argument in more detail, Section 2 digs more deeply into the controversies at each of the different levels of scientific reasoning—the ontological, the heuristic, and the methodological levels. Section 3 shows that, once the contrasting views about the first two levels are recognized, these can be used to identify four different approaches to evolutionary economics. These approaches also differ significantly in the main research topics they focus on. Section 4 turns to evolutionary game theory and argues that, although there is hardly any exchange with evolutionary economics, evolutionary game theory is faced with exactly the same kind of ontological and heuristic controversies. In Section 5 achievements and prospects for future research in evolutionary economics are assessed in relation to the different approaches. To provide a more representative picture, the assessment is based on the results of a peer survey. Section 6 offers the conclusions.

2 Why ontology and heuristics matter and methodology matters less so

As mentioned in the introduction, the question of what is specific about evolutionary economics has several facets that correspond to different levels of scientific reasoning: the ontological, the heuristic, and the methodological levels. By tracing the various interpretations of evolutionary economics back to different assumptions made at these three levels, the causes of the controversy become more transparent, and the difficulties in reconciling the diverging views can be assessed better.

To start at the ontological level, i.e. at the basic assumption about the structure of reality, one possible position is ontological monism. This means to assume that both change in the economy and change in nature belong to connected spheres of reality and are therefore potentially interdependent processes. Such an ontological continuity assumption is favored by the adherents of an ideal of the unity of the sciences (see Wilson 1998) and it involves adopting a naturalistic perspective on the human sphere. As explained elsewhere (Witt 2004), the ontological continuity hypothesis does not imply that evolution in the economy and evolution in nature are similar or even identical. The mechanisms by which the species have evolved in nature under natural selection pressure, and are still evolving, have shaped the ground for, and still influence the constraints of, man-made, cultural forms of evolution, including the evolution of the human economy. But the mechanisms of man-made evolution that have emerged on that ground differ substantially from those of natural selection and descent. Human creativity, insight, social learning, and imitative capacity have established mechanisms of a high-pace, intra-generational adaptation (Vromen 2004).Footnote 1

The implication of the ontological continuity assumption—that the economy and economic change are connected with a naturalistic substratum— is an idea that is often neglected, ignored, or even explicitly rejected in favor of a dualistic ontology. The latter treats economic and biological evolutionary processes as belonging to different, disconnected, spheres of reality.Footnote 2 As a consequence, possible influences on economic evolution that result from its historical embeddedness in evolution in nature—such as, e.g., the influences of the human genetic endowment on economic behavior—are ignored. Since these basic assumptions about reality cannot be subjected to a test, they are sometimes classified as metaphysical. They are part of a researcher’s informal world view and will therefore be dubbed her or his ‘ontological stance’.

The second level of controversy relates to the heuristic devices that guide the framing of problems and thus the way in which one arrives at conjectures and hypotheses in evolutionary economics. At this level, some authors argue that the use of particular analytical tools and models borrowed from evolutionary biology is the specific feature that distinguishes “evolutionary” from canonical economics. Here, they find themselves in the company of other social sciences where analogy constructions to biological selection models and population dynamics similarly provide the heuristic basis for conceptualizing evolution in the own domain. This may not be surprising in view of the fact that the Darwinian theory of natural selection is widely considered to be the prototype of an evolutionary theory today.

Supported by attempts at extending the Darwinian theory universally beyond the domain of evolutionary biology (Dawkins 1983), three principles of evolution have now become increasingly popular as a heuristic for evolutionary theorizing: blind variation, selection, and retention (Campbell 1965). These have been derived by abstract reduction of some key elements of the Darwinian theory of natural selection, and have been applied to conceptualizing the evolution of technology, science, language, human society, and the economy (Ziman 2000; Hull 2001; Hashimoto 2006; Hallpike 1985, 1986; Nelson 1995, respectively). The borrowing of these domain-specific abstractions by other disciplines means, of course, that they still rely on an analogy construction, albeit an abstract one. Analogy constructions and metaphors are frequently used heuristic devices in scientific work and can be very fruitful. The problem is that there is always also a risk of being lead astray by biases in, and incompleteness of, analogies. The analogy between classical mechanics and utility and demand theory in canonical economics is a well known example (see Mirowski 1989, Chap. 5). The analogy constructions in evolutionary economics are no less problematic (see Vromen 2006; Witt and Cordes 2007).

There are other heuristic strategies for conceptualizing evolution inspired not by analogies, but by a generic concept of evolution. Consider something that evolves, be it the gene pool of a species, a language spoken in a human community, the technology and institutions of an economy, or the set of ideas produced by the human mind. Although such entities can change over time in response to exogenous, unexplained forces (“shocks”), their genuinely evolutionary feature is that they are capable of transforming themselves endogenously over time. The ultimate cause of their endogenous change is the capacity to create novelty. The way in which this happens varies greatly across different domains. In the biological domain, for instance, the crucial processes are genetic recombination and mutation. These are very different from, say, the cultural processes by which new grammatical rules or new idioms emerge in the evolution of a language. Both these cases differ, in turn, from the invention of new production techniques or the emergence of new institutions in an economy.

In all these cases, the generic feature that transcends the disciplinary domains is the endogenous emergence of novelty. Yet this is not all. While novelty can be the trigger of qualitative change in the evolving entity, the actual process of transformation also depends on whether and how the novelty created disseminates and, by doing so, transforms the entity. The dissemination of novelty—the twin concept that characterizes evolution generically—is usually contingent on many factors and comes in many forms. Among them are multi-level competitive diffusion processes, like natural selection in the biological sphere, or successive adoption processes resulting from a non-selective imitation behavior as is often the case in the dissemination of human thought, practices, and artifacts. “Evolution” can thus be characterized generically—in a way that is not domain-specific—as a process of self-transformation whose basic elements are the endogenous generation of novelty and its contingent dissemination (Witt 2003, Chap.1). The generic concepts of novelty emergence and dissemination provide an overarching heuristic for interpreting problems and inducing hypotheses in the evolutionary sciences.

Since one’s ontological stance is independent of the heuristic strategy one can choose to conceptualize evolution in economics, using any one of the two-by-two combinations—monism vs. dualism and generalized Darwinian heuristic vs. generic evolutionary heuristic—is, in principle, possible. Indeed, each of the four combinations is the basis for a different interpretation of what is specific about evolutionary economics. These interpretations will be discussed in more detail in the next section. Before doing this, however, the discussion of the three levels of controversy needs to be completed with a short digression into the problems at the methodological level. Here the controversy revolves around the question of how to account for the fact that the evolution of the economy at any particular point in time results in conditions and events that are historically unique.

The controversy begins with Veblen who, in formulating his version of evolutionary economics, took the methodological position of the German Historical School (see Hodgson 2001, Chap. 1). The controversy thus has its prelude in the Methodenstreit of the late 19th century. Here is not the place to discuss that prelude. Suffice to say that Veblen’s partisanship is difficult to understand, if one were to follow the popular caricature of the Historical School’s position as an entirely descriptive, a-theoretic historicism that denies the possibility of general hypotheses and deductive reasoning in economics. There was indeed much emphasis put on working in the historical archives to register and reproduce, in a very descriptive fashion, data about the economic conditions prevailing under different institutional regimes in earlier times. However, this was not meant to imply that theoretical reasoning was not possible.

The Historical School can be seen as part of the post Enlightenment empiricism that was in vogue in the nineteenth century. In the sciences, this kind of empiricism—determined to uncover what historical reality is, what fossil remnants look like, and to record the findings—was characteristic of the Naturalist movement associated with names like Humboldt, Lyell, Herschel, Wallace, and others (Yeo 1993). After traveling all around the world, researchers filled books, journals, and session of scientific academies with reports on their observations and discoveries.Footnote 3 To understand nature meant primarily grasping its enormous variety. Something analogous to the Naturalists’ attitude seems to have appealed to Veblen, who wanted to extend the naturalistic perspective to economic evolution. Hence, his sympathy for a methodology that set out primarily to reconstruct the historical habits, institutions, technologies, etc. and the order in which they occurred over time.

Of course, if historical description were the only method to account for the fact that, at any particular point in time, the state of nature or the economy is historically unique, evolutionary biology would reduce to natural history, and evolutionary economics to economic history. Yet this did not happen. Theoretical speculations about the general causal relationships and mechanisms that manifest themselves in the historical record turned out to be possible and fruitful. Darwin’s theory of natural selection, the laws of heredity, and their more recent biophysical underpinnings are all general hypotheses about how the historical record has come about. Similarly, the particular economic conditions and events characteristic of a certain epoch may be historically unique. But this is not necessarily the case for the way in which they are generated and the patterns of transition between the states. It may be conjectured that the mechanisms of change are of more general nature, so that they produce recurrent features of change in economic history that can be explained by general hypotheses.

The methodological challenge that the historical contingency of economic phenomena poses leaves a variety of options to respond. These options are realized in different contributions to evolutionary economics, independent of their specific ontological and heuristic positions. Indeed, there seems to be a tendency across all ontological and heuristic positions to accept that different explanatory challenges require different methodological responses. One way to respond is to construct historical narratives for observed changes in technology and its knowledge base that identify, record, and make sense of, the historical sequence of events. As the work of Mokyr (1998, 2000) shows, qualitative theoretical inquiries into economic history like these can be based on a heuristic of selection analogies and metaphors. On the same basis, another methodological option is, for example, the development of sophisticated quantitative survival models to explain the historical record of the entry and exit dynamics over an industry’s life cycle (Klepper 1997).

A method of historical reconstruction that is compatible also with other heuristic strategies is the “history-friendly, appreciative” modeling approach (Malerba et al. 1999). It makes use of numerical models whose simulations can be made to fit an observed sequence of historical events or empirical time series. To match the general theoretical claims with the historical contingency condition, the models can be used to simulate counter-factual sequences of events (see Cowan and Foray 2002). Independent of the choice of the heuristic strategy, a frequently adopted methodological approach is to focus on the explanation of recurrent features of the evolutionary process rather than its historically unique outcomes. This means theorizing, e.g., about some underlying mechanisms of change or some typical transition patterns (assumed to be involved in generating historically unique outcomes without themselves being equally historically unique). A wide variety of modeling approaches is based on this methodology: diffusion models describing technological change as a result of innovativeness (Metcalfe 1988), selection models emulating competitive industrial change (Metcalfe 1994), models of path-dependence, lock-in, and critical masses in technological or institutional change (Arthur 1994; David 1993; Witt 1989). Last but not least, there is, of course, the option to develop explanatory hypotheses on the historical process of evolution itself, like, e.g., Hayek’s (1988) theory of societal evolution.

There is thus a large variety of very different methodological choices in evolutionary economics (Cantner and Hanusch 2002). They can be, and in fact are, employed in a pragmatic way to cope with the historical contingencies of evolutionary processes. It may therefore be claimed that, at least in evolutionary economics, the Methodenstreit has no longer any relevance as a source of significant controversy. It is not at the methodological level, but at the ontological and heuristic levels, that enduring controversies split the opinions in evolutionary economics and trigger some of the new developments in the field.

3 A guide to evolutionary economics

In the previous section it was argued that the differences relating to ontological stance and heuristic strategies are decisive for understanding the different approaches to evolutionary economics. They can be conveniently represented in a 2 × 2 matrix by depicting the two ontological positions against the two heuristic strategies in Fig. 1. This representation provides a guide to both the evolutionary heterodoxy and some new developments in this field. In view of the great number and variety of contributions to evolutionary economics, no attempt can, of course, be made here to discuss them in detail in the form of a survey. The more limited purpose rather is to identify what the different, overarching approaches are, and why they differ.

In the lower right cell in the matrix of Fig. 1, a dualistic, non-naturalistic ontological perspective on economics is combined with a heuristic strategy based on a generic concept of evolution. This is the position of Schumpeter (1912) in his Theory of Economic Development. It is the basis for his unique interpretation of economic development that is usually considered a seminal contribution to evolutionary economics. Schumpeter did not use of the terms “evolution” and “evolutionary” precisely because he wanted to avoid the association with the monistic Darwinian interpretation that, in his mind, the term evolution suggested.Footnote 4 When he elaborated his theory, he was guided by the notion that the economic transformation process is “intrinsically generated from within itself” (ibid. p. 75). As the source of change, he identified entrepreneurial innovations. If successful, they disseminate through imitation throughout the economy and thus transform its structure. This is exactly the generic evolutionary heuristic that focuses on the endogenous emergence of novelty and its dissemination.

However, Schumpeter did not fully exploit his ingenious insight. He used the distinction between invention and innovation to belittle the role of novelty creation (invention) and instead emphasized, in a voluntaristic fashion, the heroic character of entrepreneurship that he deemed necessary in order to be able to carry out innovations. Attention was thus shifted away from how the new knowledge on which innovations are based is being created and how the corresponding search and experimentation activities—the sources of novelty—are motivated. Furthermore, Schumpeter’s theory was inspired not least by the ongoing debate on the crisis-driven capitalist development and his own experience of the uneven growth and wealth generating industrialization process at the turn of the 19th century. This may explain why his theory of economic development is presented in terms of a theory about the unsteadiness of capitalist development, i.e. a business cycle theory. Entrepreneurs who trigger a wave of innovations and imitation occur “in swarms” and therefore induce the economy to move through phases of “prosperity and depression” in cyclical pattern.

At that time, explaining the business cycle was cutting edge research in economics. In presenting his theory of economic development as a contribution to the unfolding business cycle research, Schumpeter was able to earn himself a reputation as leading theorist in economics. But this way of selling his theory detracted attention from its non-Newtonian, evolutionary foundations. When Schumpeter (1942) later modified important parts of his theory, the evolutionary impetus was weakened even further. He claimed that, in the further development of capitalism, the role of the promoter-entrepreneur would be replaced by large, bureaucratic corporations and trusts (ibid., Chap. 7 and 12) and, thus, omitted the original psychological, motivational foundations of his entrepreneurial theory (that were difficult to reconcile with the equilibrium-cum-optimization paradigm). What he emphasized instead were the concomitants of the routine-like innovativeness of the large trusts: unprecedented economic growth and productivity increases on the one side and monopolistic practices necessary to protect the investments into innovations on the other. By arguing that it is not possible to have the one without the other, he challenged the established ideal of perfect competition. This interpretation of the competitive process—later dubbed the “Schumpeterian hypothesis”—stirred a long debate with a huge number of empirical and theoretical contributions (see Baldwin and Scott 1987). However, the broader, evolutionary connotations were increasingly lost from sight.

The unique heuristic strategy developed in Schumpeter (1912) did not find followers. None of Schumpeter’s prominent Harvard students carried it further with, perhaps, the exception of Georgescu-Roegen (see below). A resurgence of interest in Schumpeter’s pioneering evolutionary contribution had to wait until the work of Nelson and Winter (1982) and their neo-Schumpeterian synthesis. Yet this synthesis is based on a different heuristic strategy. In the debate on “economic natural selection” in the 1950s, analogies and metaphors relating to the theory of natural selection had made their appearance as a possible heuristic strategy in economics.Footnote 5 Nelson and Winter introduce this heuristic that makes metaphorical use of Darwinian concepts as a central element of their conceptualization of the transformation process in firms and industries. They thus replace the generic evolutionary heuristic that Schumpeter had used in avoiding Darwinian concepts. Indeed, within the neo-Schumpeterian camp, this switch to, and the reliance on, the Darwinian selection metaphor are often considered to be the constitutive element of evolutionary economics (e.g. in Dosi and Nelson 1994; Nelson 1995; Zollo and Winter 2002). Schumpeter’s non-monistic ontological stance in defining the disciplinary bounds of economics is factually maintained (see Nelson 2001). The neo-Schumpeterian approach therefore represents the combination of the upper right cell in Fig. 1.

In Nelson and Winter (1982), the heuristic based on Darwinian metaphors is the inspiration for an idea that has become a core concept of the neo-Schumpeterian approach: the organizational routine as a unit of selection in economic contexts. Schumpeter (1942) did not back a crucial assumption of his innovation competition hypothesis—that the corporate organizations of the large trusts have taken over the innovation process in the economy—with any specific hypotheses as to how these organizations do this. The concept of the organizational routine fills the gap. This is derived from the behavioral theory of the firm (March and Simon 1958; Cyert and March 1963)—another constitutive element of Nelson and Winter’s neo-Schumpeterian synthesis. Based on the assumption of bounded rationality, Nelson and Winter (1982, Chap. 5) argue that, in their internal interactions, firm organizations are therefore bound to use rules of thumb and develop organizational routines. Production, calculation, price setting, the allocation of R&D funds, etc. are all represented as rule-bound behavior and organizational routines.

Informed by a heuristic based on the selection metaphor, Nelson and Winter interpret organizational routines as sufficiently inert to function as the unit of selection. Accordingly, the firms’ routines are taken as the analogue to the genotypes in biology. The specific decisions resulting from the routines applied are taken as the analogue to biological phenotypes. The latter are supposed to affect the firms’ overall performance. Different routines and different decisions lead to differences in the firms’ growth. On the assumption that routines which successfully contribute to growth are not changed, the firms’ differential growth can be understood as increasing the relative frequency of successful “genes-routines”. In contrast, routines that result in a deteriorating performance are unlikely to multiply, so that their relative frequency in an industry decreases.

There is no doubt that the re-formulation of Schumpeter’s conjectures on innovativeness, industrial change, and growth in terms of selection processes operating on the organizational underpinnings of firms and industries yields important insights. Nelson and Winter demonstrate that the firms’ competitive adaptations to changing market conditions do not necessarily have to be understood as a deliberate, optimizing choice between given alternatives. Rather the adaptations may be forced on the industry by selection processes operating on the diversity of routines used in that industry. At the same time, Nelson and Winter are also able to account for the effects of innovative activities, the breaking away from old routines, in an industry’s response to changing market conditions. New ways of doing things result from search processes which are themselves guided by higher level routines. Modeled as random draws from a distribution of productivity increments, innovations raise the average performance of the industry and regenerate the diversity of firm behaviors. Selection then drives out some of the firms, while the surviving ones tend to grow. Under innovation competition, technology and industry structure thus co-evolve and feed a non-equilibrating economic growth process.

Although the concept of the organizational routine, exposed to selection, has now become something of an icon of the neo-Schumpeterian approach to evolutionary economics, the perhaps even more momentous effect that Nelson and Winter’s synthesis triggered was a different one. It prepared the ground for taking advantage of the rich body of insights on knowledge creation (neglected by Schumpeter) that in the meantime had become available in innovation research (see Dosi 1988). Indeed, the blending of innovation studies with the classical Schumpeterian themes of technological change, industrial dynamics, and economic growth has generated thriving empirical research that, in many cases, makes little, if any, use of the notion of routines and Darwinian metaphors (see Fagerberg 2003 for a survey).

On the methodological side, Nelson and Winter (1982) strongly rely on a simulation-based analysis of the implications of the selection processes operating on populations of firm routines—a methodology that has found many followers in the neo-Schumpeterian camp (e.g., Andersen 1994; Malerba and Orsenigo 1995; Kwasnicki 1996). As an analytically solvable alternative an approach based on the replicator dynamics has been suggested by Metcalfe (1994). It raises the heuristic of the selection metaphor to the level of a more stringent analogy construction. Unlike the modeling tradition in economics that focuses on the situational logic of (representative) individual behavior and its motives, the replicator dynamics—an abstract model of natural selection—focuses on the changing composition of populations and thus requires “population thinking”—a point much emphasized by Metcalfe.Footnote 6 In this version, the analogy-based heuristic then allows even the economic analogue of main theorems of population genetics to be derived.Footnote 7

In the neo-Schumpeterian approach, a non-monistic ontological stance is combined with a heuristic using Darwinian metaphors to conceptualize economic evolution. However, such a heuristic strategy is also compatible with a monistic ontological stance that suggests extending the naturalistic view of the sciences to economic behavior and the economy. This is the combination in the upper left cell in Fig. 1. It corresponds to the approach advocated by the proponents of “Universal Darwinism” (Hodgson 2002; Hodgson and Knudsen 2006). The characteristic of this approach is that it relies on an abstract analogy to, rather than a metaphorical use of, Darwinian principles: Campbell’s (Campbell 1965) variation, selection, retention principles. As already mentioned in the previous section, these have been derived by an abstract reduction of real processes in evolutionary biology and are claimed to govern evolutionary processes in all spheres of reality.

Regarding evolutionary processes in the economy, the latter claim has been met with skepticism (see Nelson 2006). Some critics object to the inevitable risks of being misled in economic theorizing by the domain specific abstractions of Universal Darwinism (Buenstorf 2006; Cordes 2006). The reasons for using a particular heuristic strategy have to do with expectations regarding the fecundity of the strategy. The question will therefore be whether the advocates of Universal Darwinism can dispel the concerns of their critics by demonstrating the fruitfulness of their heuristic in the economic domain. Up to now, not enough concrete research has been done in economics on the basis of Universal Darwinism (see, however, Hodgson and Knudsen 2004). An assessment of the pros and cons is therefore not yet possible.

Finally, the lower left cell in Fig. 1 represents the combination of a monistic ontological stance and a heuristic strategy focusing on the emergence and dissemination of novelty as generic concepts of evolution.Footnote 8 The combination is characteristic of a naturalistic interpretation of evolutionary economics that has been advocated by several writers. Since they come from quite different strands of thought, they are, however, often not recognized as following a common approach, nor is their approach usually perceived as a coherent alternative to the position of the neo-Schumpeterians. There are good reasons to associate Veblen with this position (see Cordes 2007). The arguments by which Veblen (1898) introduced the very notion of evolutionary economics to the discipline clearly indicate that what he had in mind was a naturalistic ontology, based on a Darwinian world view. His heuristic strategy is less clear. He did not provide any generic characterization of evolution. But he repeatedly emphasized human inventiveness and imitation as important drivers of the development of institutions and technology, just as the heuristic strategy in the lower left cell in Fig. 1 would suggest.

An eminent contribution to evolutionary economics, that is very explicit about taking this position, is the work of Georgescu-Roegen (1971). In line with his ontological and heuristic position, major recurring themes in his writings are the role of novelty in driving evolution and the role of entropy in constraining evolution. Both issues are given a broad methodological and conceptual discussion and are finally applied to reformulating economic production theory. In reflecting on the conditions and the evolution of production, he strongly conveys the gist of what has been called here the continuity hypothesis. This is perhaps even more true of his inquiry into the technology and institutions of peasant economies in contrast to modern industrial economies (see Georgescu and Roegen 1976, Chapters 6 and 8). His concern with the fact that natural resources represent finite stocks that are degraded by human production activities induced him to criticize the abstract logic and subjective value accounting of canonical production theories that tend to play down these concerns.

A similar criticism also motivates works in the tradition of Georgescu-Roegen’s naturalistic interpretation of evolutionary economics that link up with the emerging ecological economics movement like Gowdy (1994) and Faber and Proops (1998). Gowdy and Faber and Proops emphasize the role of the emergence of novelty, and they focus in a naturalistic perspective on production processes, their time structure, and their impact on natural resources and the environment. Blending positive evolutionary theorizing with normative environmental concerns, Gowdy and Faber and Proops also expand on the policy implications focusing on core issues of ecological economics, thus explicitly connecting the agenda of evolutionary and ecological economics.

Another eminent contribution that explicitly takes the naturalistic position, albeit with an entirely different motivation and background, is the late works of Hayek (1971, 1979, 1988, Chap. 1) on societal evolution. Hayek distinguishes between three different layers where human society evolves. A first layer is that of biological evolution during human phylogeny where primitive forms of social behavior, values, and attitudes became genetically fixed as a result of selection processes. These imply an order of social interactions for which sociobiology provides the explanatory model. (Once genetically fixed, these attitudes and values continue to be part of the genetic endowment of modern humans, even though biological selection pressure has now been largely relaxed.) At the second layer of evolution, that of human reason, evolution is driven by intention, understanding and human creativity resulting in new knowledge and its diffusion. The crucial point of Hayek’s theory is, however, that between these two layers of evolution, i.e. “between instinct and reason” (Hayek 1971), there is a third layer of evolution. This is a layer at which rules of conduct are learnt and passed on in cultural rather than genetic transmission. The process is often not even consciously recognized. Accordingly, the emergence of, and the changes in, the rules of conduct that shape human interactions and create the orderly forms of civilization are not deliberately planned or controlled.

While these conjectures correspond to the ontological continuity hypothesis discussed in Section 2, Hayek goes a step further by adding a group selection hypothesis. Which rules are transmitted and maintained, he claims, depends on whether, and to what extent, they contribute to a groups’ success in terms of economic prosperity and population growth. The latter can be brought about either as a result of successful procreation or through the attraction and integration of outsiders. A growing population fosters specialization and division of labor, and this will be the more so the case, the more reliably a group’s rules of conduct coordinate individual activities and prevent social dilemmas. By the same logic, groups that do not adopt appropriate rules are likely to decline. Hayek thus interprets cultural evolution as a differential growth process operating on human sub-populations that are defined by their common rules of conduct. The criterion of the process is the—not necessarily genetic—reproductive success which the group’s rules enable. From his hypotheses Hayek draws far-reaching conclusions regarding the political economy of the “extended order of the markets” that he considers the main human cultural achievement (see Hayek 1988).

It is worth noting that Hayek’s group selection hypothesis does not necessarily involve natural selection operating at the level of the genes. It thus differs from the “dual inheritance hypothesis” in anthropology (see Henrich 2004; Richerson and Boyd 2005). The latter holds that gene-based natural selection processes and cultural learning jointly developed an impact on reproductive success in early phases of human phylogeny in which selection pressure was high. In the dual inheritance model, the cultural learning component explains why group selection is possible where natural selection alone would be bound to kin selection.

Unlike both Hayek’s (tacit) cultural learning theory and the dual-inheritance hypothesis, the theory of economic change recently put forward by North (2005) emphasizes the role of human cognition. Culture, institutions, and technology matter for economic evolution, not least through their influence on transaction costs as a measure of social efficiency. But the true driving forces in North’s view are human intentionality, beliefs, insight (i.e. cognitive learning), and knowledge. These make economic change for the most part a deliberate process. Accordingly, North directs attention to what is learned and how it is shared among the members of a society. The emphasis he puts on human learning and knowledge creation—i.e. the emergence of novelty—and the sharing of experience-based knowledge within and between generations—i.e. dissemination of novelty—points to a heuristic similar to the one based on the generic concept of evolution. Moreover, unlike his early contributions to new institutional economics (see Vromen 1995), North (2005) clearly takes a naturalistic ontological stance. Much like Hayek, he is eager to define the relationship between his explanatory sketch of economic evolution and the Darwinian world view, and the way he does so correlates with the ontological continuity hypotheses. Hence, North (2005) can be assessed as an important recent contribution to the naturalist interpretation of evolutionary economics.

As the discussion has shown, the four combinations of ontological stances and heuristic strategies in Fig. 1 correspond to four different interpretations of what is specific about evolutionary economics. Of these interpretations, the neo-Schumpeterian and the naturalistic interpretation have been those most actively elaborated in recent times, the former clearly more so than the latter. These two schools of thought differ significantly in the main research topics they focus on. In a nutshell, the neo-Schumpeterian themes are innovation, technology, R&D, organizational routines, industrial dynamics, competition, growth, and the institutional basis of innovation and technology. The themes of the naturalistic approach are long-term development, cultural and institutional evolution, production, consumption, and economic growth and sustainability.

The difference in perspective is not accidental. The naturalistic interpretation offers substantial new insights, particularly in a comparative, long-run analysis of the economic evolutionary process, while it makes less of a difference, e.g., for economic theorizing on short run industrial dynamics and competitiveness. However, this does not mean that the naturalistic approach cannot fruitfully be extended to the neo-Schumpeterian agenda. For example, production and consumption are important, but somewhat neglected, research topics that are relevant also for the neo-Schumpeterian agenda. Integrating the naturalistic approach with these topics can therefore be expected to add significantly to the understanding of the structural transformation of industries, economies, and international trade patterns.

4 Ontology and heuristics in evolutionary game theory

Many references in Hayek’s work on his theory of societal evolution show that he draws to a considerable extent on the early sociobiology debate for which the introduction of game-theoretic arguments played a constitutive role (Caplan 1978). On the basis of a qualitative analysis, Hayek’s theory of how societal evolution works therefore anticipates results that were later established in a more rigorous form in the unfolding field of evolutionary game theory in economics. In fact, his hypotheses on cultural learning at the layer “between instinct and reason”, and the key role that rules of conduct play for coordination and prevention of social dilemmas, can be reproduced in elaborate game-theoretic terms (see, e.g., Witt 2008). In a sense, Hayek’s contribution can thus be seen as an early outline of what a naturalistic approach to evolutionary game theory could mean. With regard to ontological stances and heuristic strategies, there is indeed a similar divide between the different interpretations of evolutionary game theory in economics as diagnosed in the previous section for evolutionary economics. Furthermore, as in the case of evolutionary economics, the authors often do not seem aware of the assumptions they implicitly make.

Compared to rational game theory, the distinctive features of evolutionary game theory are special assumptions about how strategies are determined and, as a consequence, special solution concepts.Footnote 9 These assumptions follow from, and are designed to meet, the explanatory requirements of evolutionary biology, particularly sociobiology (Trivers 1971; Wilson 1975; Maynard Smith 1982). With the rise of game theory as a major field of research in economics, the interest of some authors was also attracted to evolutionary game theory. This interest may sometimes be due more to the formal properties of evolutionary game theory than to an intention to seek applications to economic problems (see, e.g., Weibull 1995). Because of the special assumption built into evolutionary game theory, such applications are indeed not easy to find (Friedman 1998). These assumptions make sense in sociobiology when arguing how certain forms of genetically determined social behavior, e.g. altruistic forms, can emerge under natural selection. It is not evident, however, what kind of economic behavior is supposed to meet the assumptions of evolutionary game theory.

Applications of evolutionary game theory in the economic domain follow basically two interpretations. A first interpretation takes over models of interactive selection mechanism and the corresponding algorithms from evolutionary biology in order to model human interactive learning processes in an economic context (usually non-cognitive learning behavior like reinforcement or stimulus-response learning, see Brenner 1999, Chap. 6). This is not meant to claim that the biological mechanisms apply directly to economic behavior—an idea that would not make sense because human learning is a non-genetic adaptation process. The interpretation is rather based on the heuristic strategy of assuming an analogy between genetic adaptation mechanisms and the non-genetic adaptation through non-cognitive learning. The formal background for the analogy is replicator dynamics that covers a very broad class of adjustment process (see Hofbauer and Sigmund 1988; Joosten 2006). In ontological terms, i.e. with respect to the basic assumptions about the structure of reality, the analogy construction typically neglects the question of whether, and how, economic processes modeled in that way connect with the naturalistic foundation of human behavior. This combination is thus the same as the one in the upper right cell in Fig. 1.

For the second interpretation of evolutionary game theory, by contrast, the biological context for which evolutionary game theory was originally developed is directly relevant to the political economy applications this interpretation deals with. It is claimed that certain very basic features of human economic behavior, like altruism, moral behavior, fairness, and other rules of conduct, have a genetic background and can therefore be best explained as a result of natural selection (see, e.g., Güth and Yaari 1992; Binmore 1998; Gintis 2007). Similar to the continuity hypothesis, the existence of such features of human behavior is traced back to their conjectured emergence at the times of early human phylogeny when natural selection pressure on the human species was still high enough to shape behavior according to what can be speculated to have raised genetic fitness. Unlike in the former interpretation, such a view obviously presumes a monistic, naturalistic ontology. The heuristic strategy is not explicitly dealt with, but it has some similarity with Hayek’s theory of societal evolution. In Binmore (1998) the game-theoretic argumentation is used to establish the particular content, e.g. in terms of the notion of fairness and justice, of the rules of conduct that emerged initially in human phylogeny. Because of its genetic background, the content is still effective and is argued to imply two basic coordination mechanisms for human societies, leadership and fairness (see also Binmore 2001).

In view of the two interpretations, it is striking how similar the understanding of the specific meaning of the attribute “evolutionary” is in evolutionary game theory and evolutionary economics. They share similar ontological stances and heuristic strategies and even develop a similar schism in these respects. But researchers in these two fields take little notice of each other. There is hardly any cross reference between the two fields, even when scholars from both camps join in symposia or conferences.Footnote 10 In a rare attempt to explain the mutual lack of exchange, Nelson (2001) argues that evolutionary game theory differs in two ways from evolutionary economics. First, it is more equilibrium oriented—even when the adjustment dynamics are explored this mainly serves the understanding of the resulting equilibrium configurations. Second, evolutionary game theory is less empirically oriented, paying little tribute to analyzing the historical record of the evolutionary process. For these reasons, Nelson argues, the two research communities have less in common than might be expect. In a similar vein, Dosi and Winter (2002) argue that evolutionary game theory is mostly theory-driven while evolutionary economics is more experience-driven, leaving little common ground for exchange.

In the light of the present discussion, a distinction can, however, be made between the naturalistic and the non-naturalistic approaches to evolutionary game theory on the one side and to evolutionary economics on the other. The non-naturalistic approaches do not have much more in common than the construction of analogies to natural selection—in the one case with, in the other without, strategic interaction—by means of concepts imported from evolutionary biology. In such a situation, there seems to be little opportunity to gain from trade. The naturalistic approaches, in contrast, share the explanation of human economic behavior by recourse to genetic and behavioral dispositions. This creates much more commonality in substance (as, e.g., the line of thought reaching from Hayek’s theory of societal evolution to Binmore’s theory of social contract may show). Factual lack of exchange may here simply be due to the small number of researchers who follow, at one time, a naturalistic approach in their own field.

5 Recent trends in the evolutionary agenda—a peer survey

It has been argued above that Schumpeter’s original interpretation has no more followers today and that Universal Darwinism is only just starting substantial work in economics. Of the four different interpretations of evolutionary economics in Table 1 only two—the neo-Schumpeterian and the naturalistic—are therefore currently leading to significant research output. These two differ significantly in the topics they deal with. If there were only the diverging research interests, the two schools could be seen as complementary. However, there is also a difference between the two in the basic assumption they make about reality and the way in which they approach, and theorize about, evolutionary processes in the economy. This is not easily reconcilable. In this section, an attempt will be made to assess the achievements and prospects for future research in evolutionary economics in relation to these two main interpretations.

In order to put this assessment on a broader basis, this section draws on the results of a survey conducted in 2004. A questionnaire in which they were asked about their opinion was sent out by e-mail to 149 academic scholars all over the world. The scholars were selected according to the criterion of whether they had at least one publication where they had dealt with, and had explicitly used the term, evolutionary economics.Footnote 11 The questionnaire contained several questions.

The first question aimed at getting an assessment from the respondents about what has been accomplished by past research into evolutionary economics. The precise formulation was: “Summarizing evolutionary economics’ achievements, what would you consider the most significant insights that have so far been gained? (Please give 4 or 5 keywords or names of contributors.)” In order to derive a survey statistic from the answers, the keywords quoted in the questionnaires returned were categorized into classes of synonyms and near-synonyms that were given a representative label, and the number of designations that fell into the various keyword classes were counted. The keyword class then had to be identified, if possible, with one of the interpretations of evolutionary economics in Fig. 1, an identification that was done according to the author’s best knowledge. In view of the fate of Schumpeter’s position, and because of the early stage in which Universal Darwinism currently is, the neo-Schumpeterian interpretation and that of the naturalist approaches are most likely the research programs to be associated here.

Of the 149 questionnaires sent out, 53 (36%) were returned.Footnote 12 Since some of the keywords given in the questionnaires could not be associated with any, or only very few, other keywords, a relatively large number of 48 different keyword classes resulted. For space reasons, only the 16 keyword classes with at least five designations—i.e. keywords quoted by at least roughly one tenth of all respondents—are reported in Table 1 together with the percentage of the 53 respondents that quoted the (near-) synonyms. The table also ranks the number of designations of the keyword classes differentiated by the professional status of the respondents. Furthermore, in the last column of Table 1, the keyword classes are associated with one of the interpretations of evolutionary economics.

For characterizing the achievements of evolutionary economics, the two keyword classes quoted most often in the sample were: “innovations and endogenous technological change” and “evolution of institutions and norms”. With only one fourth of all respondents mentioning these keyword classes—and even smaller shares mentioning other classes—there is only modest agreement as to what the most significant insights in evolutionary economics are. Furthermore, the differences between professors and younger scholars in what they assess as an achievement or an insight in evolutionary economics are striking. The Spearman rank correlation coefficient for the two rank orders in Table 1 is very small (r s = 0.051), indicating that there is almost no correlation between them. Given that the class label “innovations and endogenous technological change” seems highly significant for the dominant neo-Schumpeterian agenda, a share of only 26% may be surprising. Yet, in view of the fact that 6 of the 16 class labels can also be identified with the neo-Schumpeterian research agenda, this agenda is not under-represented. On the contrary, if the identification in Table 1 of the keyword classes with the alternative research programs is accepted, the neo-Schumpeterian school is obviously perceived by the respondents as the most important and successful. As indicated, seven of the remaining keyword classes can be claimed for both research programs, two seem unclear, and only one—“spontaneous order”—can, with some right, be considered associated with the naturalistic program.Footnote 13

A second issue addressed by the questionnaire concerned the opinions about promising topics for future research in evolutionary economics. The precise formulation of the question was: “What would you consider the most promising new developments in evolutionary economics since 1990? (Please give 4 or 5 keywords or names of contributors.)” Again, the procedure was to form classes of keywords from synonyms and near synonyms and to check how far they are associated with any of the two schools. For this question, 44 different keyword classes resulted of which 13 obtained at least five designations. These are presented in Table 2, together again with the percentage of the respondents, the ranks of the number of designations differentiated by the professional status of the respondents, and the associations with the research agendas of the different schools in evolutionary economics.

To characterize the most promising new developments, the keyword class “integrating the institutional side” was quoted most often in the sample. This is a conceptual issue that presently figures prominently in the neo-Schumpeterian camp (see, e.g., Nelson and Sampat 2001) that has up to now been strongly technology-oriented. Second in designation frequency are “agent-based modeling tools and computational methods” and “cognitive aspects” (of the evolutionary approach to economics)—the former a methodological/technical point that is not specific to any of the two schools, the latter again a conceptual issue relevant to both schools. The keyword label “industry evolution and life cycles” that is next in relative frequency already appeared in Table 1 as major insight and is therefore in italics. The same holds for “knowledge creation and use” and “evolutionary game theory”. Unlike the other ten keyword classes that signal a certain shift in interest or emphasis when turning from the past to the future, the keywords in italics seem to be considered as topics with continuing high potential.

As far as the identification with the two schools is concerned, the neo-Schumpeterian themes are represented somewhat less than before, but the naturalists’ topics have not gained more support. What does seem to be gaining ground is the interest in formal modeling and the corresponding tools (“agent-based and computational methods”, “network models”, “complex economic dynamics”). The differences between professors and younger scholars in what they consider promising new developments in evolutionary economics are once again remarkable, albeit less spectacular than in Table 1. (For the two rank orders in Table 2, r s = 0.345, at a significance level 0.248).

The results of the peer survey show that, of the two main interpretations of evolutionary economics, the neo-Schumpeterian approach is perceived more prominently and its achievements are more widely appreciated than is the case for the naturalistic interpretation. This is not surprising in view of the fact that these days, the majority of research activities in evolutionary economics focus on innovations, technology, R&D, organizational routines, industrial dynamics, competition, growth, and the institutional basis of innovations and technology. These topics reflect the strong impact that Nelson and Winter (1982) and their neo-Schumpeterian synthesis had, and still have, on the field and on the self-perception of many scholars contributing to evolutionary economics today. If judged by the survey results, the contributions to the naturalistic interpretation—from Veblen (the inventor of “evolutionary” economics) to Georgescu-Roegen, Hayek, North, and others—do not seem to have much resonance in evolutionary economics today.

Regarding the promising prospects for future research, the situation is less one-sided. In part this is due, however, to the stronger influence of formal methods. These attract the interest particularly of the younger participants in the survey, and they have no particular association with any of the alternative interpretations. There are no signs of convergence as far as the two main interpretations of evolutionary economics are concerned. The potential of the naturalistic interpretation is still not really recognized by the evolutionary economists. Its characteristic topics—long-term development, cultural and institutional evolution, production, consumption, and economic growth and sustainability—deserve more attention. They can help to avoid the impression one can get today that evolutionary economics is basically a competitor to canonical industrial economics. By embracing a wider range of topics, among them traditional themes since the classics, the naturalistic agenda broadens the scope of evolutionary economics. What is more, with its foundations in a Darwinian world view, it can also challenge canonical economics and its mix of Newtonian thought and radical subjectivism.

6 Conclusions

There is little agreement among the researchers in the field when it comes to deciding what is specific about evolutionary economics. As has been shown in this paper, some interpretations of evolutionary economics consider the Darwinian theory of evolution relevant for understanding economic behavior and the transformation of economic institutions and technology. Other interpretations do not embrace, or even explicitly reject, that idea. At the core, this is a controversy about the basic (ontological) assumption about the structure of reality. It relates to the question of whether evolutionary change in nature and in the economy represent connected spheres of reality, making them likely to mutually influence each other.

In a different sense, the role of Darwinian theory is also relevant for a second controversy. This revolves around the question of whether evolutionary theorizing in economics can profit from borrowing analytical tools from evolutionary biology, e.g. models of selection processes and population dynamics. As has been explained, some authors consider the application of such models to economic processes on the basis of analogies or metaphors to be the specific feature of the evolutionary approach to economics. Other authors have different ideas. To construct analogies between, and to use metaphors originating from, different disciplinary domains is a heuristic device, i.e. a way of framing problems and of arriving at hypotheses. Unlike the previous controversy, the one about whether or not to borrow analytical tools from evolutionary biology thus refers to the heuristic level. The way it is decided is independent of the ontological position taken, but is decisive for the form of theorizing in evolutionary economics.

Finally, there is a controversy relating to the methodological level, particularly to the problem that economic evolution is a historical process producing historically unique conditions and events: how should this fact be accounted for in evolutionary economics? The controversy has been claimed to be independent of the other two. As was discussed in the paper, some authors have tried to account for the question by relying on qualitative reasoning. Others have responded by developing a “history friendly” modeling strategy. However, it can also be argued that, while at any given time the results of evolution may be historically unique, the processes by which they are generated are not necessarily historically unique. (In fact, if this were not so, it would be pointless to claim that the way in which evolution works can be explained by more general hypotheses.) It can therefore be concluded that with the variety of choices, and the usually pragmatic decision making as to which of them to select, the methodological level is not the reason for the views on what is specific about evolutionary economics being different.

The major differences indeed result from diverging ontological stances and heuristic strategies. This turned out to be true also for evolutionary game theory which is faced with exactly the same kind of ontological and heuristic controversies. Juxtaposing the two positions that have been identified at each of the two levels results in a convenient two-by-two matrix. In the paper this matrix has served as a guide to the various interpretations of evolutionary economics that can be found in the literature. Not all interpretations corresponding to the four cells in the matrix have received equal attention. In recent years, the combination of Darwinian concepts at the heuristic level and neglect or rejection of a naturalistic monism at the ontological level is most frequent. This combination is characteristic of the neo-Schumpeterian approach. As was shown, this has not always been so. Schumpeter’s own approach differed from that of the neo-Schumpeterian. There has also been a naturalistic interpretation of evolutionary economics advocated by such diverse scholars as Veblen, Georgescu-Roegen, Hayek, and North. The most recent development—Universal Darwinism—has been recommended as an approach to evolutionary economics that favors yet another combination of ontological stance and heuristic strategy.

The scientific value of the alternatives should be measured in terms of the insights they deliver on the transformation processes in the economy. To assess the fruitfulness of the alternative interpretations, a peer survey was conducted to identify achievements in past research and promises for future research in evolutionary economics. In the overall ranking of past achievements expressed in the opinion poll, the neo-Schumpeterian position was found to stand out. In the assessment of promising future research the picture is somewhat different. However, there is little evidence for convergence, or for a real resurgence of interest in the naturalistic approach to evolutionary economics. Such a resurgence would seem desirable in order to broaden the agenda of evolutionary economics beyond the neo-Schumpeterian themes that basically rival the canonical theories of industrial economics and technological change. Not only would topics like long-term development, cultural and institutional evolution, production, consumption, and economic growth and sustainability have a come-back on the evolutionary agenda. Founded on a Darwinian (naturalistic) world view, evolutionary economics would also challenge in principle terms the mix of Newtonian thought and radical subjectivism characteristic of canonical economics.

Notes

From the point of view of the continuity hypothesis, the relevance of the Darwinian theory of evolution for explaining economic change is therefore that of a meta-theory. Not unlike in evolutionary psychology (see Tooby and Cosmides 1992), it allows the genetic endowment, fixed at times when early humans were under fierce selection pressure, to be reconstructed along with the influence it still has on economic behavior today. Furthermore, on this basis, the conditions under which economic evolution took off in the early human phylogeny can be reconstructed. A comparison with the conditions of modern economies is not only conducive to taking a naturalistic perspective on the latter, but it also helps to better grasp the historical path of the development, see Witt (2003, Chap. 1) for a more detailed discussion.

In broader perspective, the historical contingency of empirical phenomena is by no means exclusively a problem in economics. It is center stage in the great transition in the sciences from the a-historic, Newtonian world view to an evolutionary one during the Darwinian revolution (Moore 1979). It is worth noting that the ground for the transition was prepared by the Naturalists’ empiricism (Mayr 1991, Chap. 1).

See Schumpeter (1912, Chap.7). The chapter was omitted from later editions and the English translation of 1934. It has appeared only recently in English translation (Schumpeter 2002). In this chapter, Schumpeter is quite explicit in criticizing the pure theory of economics of his time because of its flawed Newtonian equilibrium heuristic. But he did not distance himself from the dualistic ontological position of that theory.

Alchian (1950), Penrose (1952), Friedman (1953). The core of the debate was whether, in a competitive market, a firm can survive if it is not profit maximizing—an attempt to employ the selection metaphor to rectify profit maximizing behavior. However, on closer inspection, it turns out that the profit level sufficient to ensure survival at a particular time, and in a particular market, varies with so many factors that no unique profit maximum can be determined, see Winter (1964), Metcalfe (2002).

The flip side of the coin is that the assumption of selection operating on routines and population thinking makes it difficult to account for individual learning, problem solving, and strategic reorientation—as important as they may be for the firms’ adaptations to changing market conditions. Focus is at the industry level. Improved average performance in the industry is explained exclusively in terms of changing relative frequencies of the organizational routines that are themselves unchanging.

These are Fisher’s principle and Kimura’s theorem, see Metcalfe (2002). The former states that natural selection raises average fitness in a population to the level of the highest individual fitness, the pace of change of the mean population fitness being proportional to the variance of the individual fitness. In the economic analogue, fitness is expressed by profit differentials between competing firms. In population genetics, mutation and cross-over again increase variety continuously. The analogue in economics, Metcalfe (1998) argues, is Schumpeter’s notion of the creative (innovative) destruction. By improving products, technology, organizational routines, etc. profit differentials are built up anew. Variety reducing and variety increasing processes taken together establish the “capitalist engine of growth”.

Unlike Universal Darwinism, this position does not claim that the explanation of evolution in nature and evolution in the economy can identically be reduced to the abstract Darwinian principles of variation, selection, and retention. Instead, the latter are seen as special, and therefore often not relevant, materializations of what drives evolution generically: the emergence and dissemination of novelty. Consequently, for this position, the role which the Darwinian theory plays is defined by the ontological continuity hypothesis, see footnote 1 above.

A player does not choose among strategies, but rather represents one fixed strategy out of a set of strategies present in a population of potentially interacting players. Players (or strategies) are matched randomly for single interactions. Their pay-offs are defined in terms of fitness values. Differences between the players’ pay-offs result in a corresponding marginal change of the relative frequencies of the respective strategies in the population. See, e.g., Friedman (1998).

Although this is an objective selection criterion, it cannot be claimed that the selection of scholars is free from subjective biases and that it forms a representative sample of all authors who satisfy the criterion. Furthermore, the lack of anonymity in the e-mail based response mode may have had an impact on who was willing to respond and in what way. The survey results may therefore be subject to selection biases.

By geographical status came 43 from Europeans and 10 non-Europeans. By professional status, 37 respondents were professors and 16 were at an earlier stage of their career (post-docs, lecturers, researchers, etc.—because of their average age denoted “younger scholars” below).

The keyword class “evolution of institutions and norms” demonstrates the difficulties involved in the identification task. It can be identified with Veblen’s institutionalist agenda, with Hayek’s and North’s agenda, and with that of evolutionary game theory (evolutionary game theory itself was only among the less frequently (9%) mentioned achievements)—mostly naturalistic interpretations. However, the keyword class could also be claimed to be significant for the institutional underpinnings of national innovation systems, a neo-Schumpeterian theme.

References

Alchian AA (1950) Uncertainty, evolution, and economic theory. J Polit Econ 58:211–221

Andersen ES (1994) Evolutionary economics—post-Schumpeterian contributions. Pinter, London

Andersen ES (2004) Population thinking, Price’s equation and the analysis of economic evolution. Evol Inst Econ Rev 1:127–148

Arthur WB (1994) Increasing returns and path dependence in the economy. University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor

Baldwin WL, Scott JT (1987) Market structure and technological change. Harwood Academic Publishers, Chur

Binmore K (1998) Just playing-game theory and the social contract II. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA

Binmore K (2001) Natural justice and political stability. Journal of Institutional and Theoretical Economics 157:133–151

Brenner T (1999) Modelling learning in economics. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham

Buenstorf G (2006) How useful is generalized Darwinism as a framework to study competition and industrial evolution? J Evol Econ 16:511–527

Campbell DT (1965) Variation and selective retention in socio-cultural evolution. In: Barringer HR, Blankstein GI, Mack RW (eds) Social change in developing areas: a re-interpretation of evolutionary theory. Schenkman, Cambridge, MA, pp 19–49

Cantner U, Hanusch H (2002) Evolutionary economics, its basic concepts and methods. In: Lim H, Park UK, Harcourt GC (eds) Editing economics. Routledge, London, pp 182–207

Caplan AL (ed) (1978) The sociobiology debate. Harper, New York

Cordes C (2006) Darwinism in economics: from analogy to continuity. J Evol Econ 16:529–541

Cordes C (2007) Turning economics into an evolutionary science: Veblen, the selection metaphor, and analogical thinking. J Econ Issues 41:135–154

Cowan R, Foray D (2002) Evolutionary economics and the counterfactual threat: on the nature and role of counterfactual history as an empirical tool in economics. J Evol Econ 12:539–562

Cyert RM, March JG (1963) A behavioral theory of the firm. Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ

Dawkins R (1983) Universal Darwinism. In: Bendall DS (ed) Evolution from molecules to man. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 403–425

David PA (1993) Path-dependence and predictability in dynamical systems with local network externalities: a paradigm for historical economics. In: Foray DG, Freeman C (eds) Technology and the wealth of nations. Pinter, London, pp 208–231

Dopfer K (2005) Evolutionary economics: a theoretical framework. In: Dopfer K (ed) The evolutionary foundations of economics. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 3–55

Dopfer K, Potts J (2004) Evolutionary realism: a new ontology for economics. J Econ Methodol 11:195–212

Dosi G (1988) Sources, procedures, and microeconomic effects of innovation. J Econ Lit 26:1120–1171

Dosi G, Nelson RR (1994) An introduction to evolutionary theories in economics. J Evol Econ 4:153–172

Dosi G, Winter SG (2002) Interpreting economic change: evolution, structures and games. In: Augier M, March JG (eds) The economics of choice, change and organization. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, pp 337–353

Faber M, Proops JLR (1998) Evolution, time, production and the environment. Springer, Berlin

Fagerberg J (2003) Schumpeter and the revival of evolutionary economics. J Evol Econ 13:125–159

Foster J (1997) The analytical foundations of evolutionary economics: from biological analogy to economic self-organization. Struct Chang Econ Dyn 8:427–451

Friedman D (1998) On economic applications of evolutionary game theory. J Evol Econ 8:15–43

Friedman M (1953) The methodology of positive economics. In: Friedman M (ed) Essays in positive economics. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp 3–43

Georgescu-Roegen N (1971) The entropy law and the economic process. Harvard Univ. Press, Cambridge, MA

Georgescu-Roegen N (1976) Energy and economic myths—institutional and analytical economic essays. Pergamon, New York

Gintis H (2007) A framework for the unification of the behavioral sciences. Behav Brain Sci 30:1–61

Gowdy J (1994) Coevolutionary economics: the economy, society and the environment. Kluwer, Boston

Güth W, Yaari M (1992) Explaining reciprocal behavior in simple strategic games: an evolutionary approach. In: Witt U (ed) Explaining process and change—approaches to evolutionary economics. University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, pp 23–34

Hallpike CR (1985) Social and biological evolution I. Darwinism and social evolution. J Soc Biol Syst 8:129–146

Hallpike CR (1986) Social and biological evolution II. Some basic principles of social evolution. J Soc Biol Syst 9:5–31

Hashimoto T (2006) Evolutionary linguistics and evolutionary economics. Evol Inst Econ Rev 3:27–46

Hayek FA (1971) Nature vs. nurture once again. Encounter 36:81–83

Hayek FA (1979) Law, legislation and liberty. The political order of a free people, vol 3. Routledge, London

Hayek FA (1988) The fatal conceit. Routledge, London

Henrich J (2004) Cultural group selection, coevolutionary processes and large-scale cooperation. J Econ Behav Organ 53:3–35

Herrmann-Pillath C (2001) On the ontological foundations of evolutionary economics. In: Dopfer K (ed) Evolutionary economics—program and scope. Kluwer, Boston, pp 89–139

Hodgson GM (2001) How economics forgot history: the problem of historical specificity in social science. Routledge, London

Hodgson GM (2002) Darwinism in economics: from analogy to ontology. J Evol Econ 12:259–281

Hodgson GM, Knudsen T (2004) The firm as an interactor: firms as vehicles for habits and routines. J Evol Econ 14:281–307

Hodgson GM, Knudsen T (2006) Why We need a generalized Darwinism, and why generalized Darwinism is not enough. J Econ Behav Organ 61:1–19

Hofbauer J, Sigmund K (1988) The theory of evolution and dynamical systems. Cambridge Univ. Press, Cambridge.