Abstract

Global navigation satellite systems (GNSS) underpin a number of modern life activities, including applications demanding positioning accuracy at the level of centimetres, such as precision agriculture, offshore operations and mining, to name a few. Precise point positioning (PPP) exploits the precision of the GNSS signal carrier phase measurements and may be used to provide the high accuracy positioning needed by these applications. The Earth’s ionosphere is critical in PPP due to its high variability and to disturbances such as scintillation, which can affect the satellite signals propagation and thereby degrade the positioning accuracy, especially at low latitudes, where severe scintillation frequently occurs. This manuscript presents results from a case study carried out at two low latitude stations in Brazil, where a dedicated technique is successfully applied to mitigate the scintillation effects on PPP. The proposed scintillation mitigation technique improves the least square stochastic model used for position computation by assigning satellite and epoch specific weights based on the signal tracking error variances. The study demonstrates that improvements in the 3D positioning error of around 62–75% can be achieved when applying this technique under strong scintillation conditions. The significance of the results lies in the fact that this technique can be incorporated in PPP to achieve the required high accuracy in real time and thus improve the reliability of GNSS positioning in support of high accuracy demanding applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The Earth’s ionosphere is the single largest contributor to the global navigation satellite system (GNSS) positioning error budget and although the bulk of its effect on the propagation of GNSS signals can be generally modelled to a first order, its state can be very erratic, depending on location, season, local time, solar and geomagnetic activity. Particularly around solar cycle maxima, the ionosphere may become exceptionally disturbed and severely degrade satellite signal propagation, affecting in particular real-time high accuracy GNSS carrier phase-based techniques such as precise point positioning (PPP), real-time kinematic (RTK) and network RTK (NRTK). Ionospheric scintillation, characterised by rapid fluctuations in the signal amplitude and phase, is potentially the most critical effect degrading GNSS high accuracy positioning performance. Effects are more severe over the equatorial/low latitudes, where scintillation occurrence is associated with the crests of the equatorial ionization anomaly (EIA) centred approximately 15° in latitude on either side of the geomagnetic equator (Basu et al. 2002). Studies carried out at equatorial/low latitudes have indicated that scintillation occurrence is prevalent during the equinoxes and it is mainly a post-sunset phenomenon, maximising during 19-01 local time (Muella et al. 2013; Ji et al. 2013). Strong scintillation is capable of leading to loss of satellite signal tracking and especially phase tracking (Skone et al. 2001; Doherty et al. 2003; Sreeja et al. 2012), which is crucial to high accuracy professional applications relying on a real-time capability.

The effects of low latitude scintillation on GNSS positioning have been reported over decades in the literature. For instance, Groves et al. (2000) showed that a global positioning system (GPS) receiver located in the Ascension Island experienced several navigation outages between 20 and 90 min duration in the strong scintillation environment. Analysing data during the period of solar maximum around 1999–2000, Skone and Shrestha (2002) reported that degradation in differential GPS (DGPS) horizontal and vertical positioning near the equatorial anomaly in Brazil led to errors of 25–30 m in the 20–24 local time period during equinoctial months. During periods of intense scintillation activity in Thailand, Dubey et al. (2006) illustrated that positioning errors of GPS single point positioning (SPP) using single frequency data can reach tens of meters. Using dual-frequency GPS data collected in Africa, Moreno et al. (2011) reported variations of up to 4 m in altitude under scintillation for single epoch positioning of PPP. Xu et al. (2012) demonstrated that the largest PPP error under strong scintillation in Hong Kong with GPS dual-frequency data can increase to more than 34 cm and 20 cm, respectively, in the vertical and horizontal components. The Beidou dual-frequency PPP results over Hong Kong presented in Luo et al. (2018) indicated root mean square (RMS) values of positioning errors in the horizontal and vertical components to be larger than 0.5 m under scintillation conditions. These studies from low latitudes highlight that GNSS positioning errors can increase several orders of magnitude under intense scintillation conditions.

Several approaches have been proposed to improve the positioning performance under scintillation. One approach is to enhance the robustness of the GPS receiver carrier tracking loop by implementing various enhanced tracking algorithms such as a Kalman filter-based phase lock loop (PLL) (Humphreys 2005; Susi et al. 2017), frequency lock loop (FLL)-assisted PLL (Zhang and Morton 2009) and FLL-assisted PLL with in-phase pre-filtering (Xu et al. 2015). A second approach is to exclude the subset of scintillation-affected satellites, especially with the increase in the number of satellites with multiple GNSS systems. In this case, the amount of available observables for positioning is reduced, thus possibly weakening the solution reliability, depending on the resulting satellite geometry. The success of this approach is therefore governed by the amount and location of the excluded satellites in relation to the overall satellite geometry. In this manuscript, satellite exclusion approaches are not considered, instead the intention is to model the effects of scintillation considering all the satellites tracked by the receiver, therefore ensuring the strongest possible satellite geometry. A third approach is based on improving the data processing algorithm such as by providing a more realistic stochastic model (Aquino et al. 2009; Silva et al. 2010; Weng et al. 2014), a robust iterative Kalman filter combined with data snooping for further quality control (Zhang et al. 2014) and an advanced stochastic model coupled with suitable total electron content (TEC) information (Park et al. 2017). Vani et al. (2019) described a scintillation mitigation approach consisting of three steps, namely a new functional model to correct the effects of range errors in the observables, a new stochastic model that uses these corrections to assign different precisions for the observables and a strategy to attenuate the effects of losses of lock and consequent ambiguities re-initializations. The use of modernised GPS L2C measurements in GNSS positioning (Marques et al. 2016) and using multi-constellation GNSS data (Marques et al. 2018) to improve positioning accuracy under scintillation have also been attempted. Although these studies have provided encouraging results, the effectiveness of these approaches depends also on the severity of the scintillation conditions. For example, using the approach proposed in Zhang et al. (2014), the positioning accuracy reaches about 20–30 cm in the vertical direction during periods of strong scintillation after a short initialization period. Marques et al. (2016) pointed out that the use of GPS L2C for PPP can provide improvement in accuracy only under weak scintillation conditions. Even by integrating GPS and GLONASS observations as presented in Marques et al. (2018), the RMS of the 3D positioning accuracy under moderate to strong scintillation conditions can still be as poor as 36 cm. Using the approach of Vani et al. (2019), the standard deviation of 3D RMS error under strong scintillation conditions reaches about 0.19–0.51 m.

The study presented in this manuscript finds its motivation on the promising results presented in Aquino et al. (2009) and Silva et al. (2010), where a strategy to improve the least squares (LSQ) stochastic model used in GNSS position computation was introduced and successfully demonstrated to mitigate the effects of high latitude scintillation. The strategy was based on the scintillation sensitive receiver tracking models described in Conker et al. (2003), through which the variance of the output error of the receiver PLL and delay-locked loop (DLL) can be estimated. The assumption was that the ability of such models to incorporate phase and amplitude scintillation effects into the variance of the individual satellite-receiver link tracking errors allows the assignment of relative weights to the corresponding measurements in the stochastic model of the LSQ solution. This was shown to bring an advantage over the commonly adopted ‘equal weights per observable type’ or ‘satellite elevation angle based weights’ stochastic models. Moreover, in those two papers, the focus was exclusively on experiments undertaken in Europe, in particular at geographic latitudes approaching ~ 80° N, where the processes leading to and the observation of scintillation differ significantly from the low latitude regions.

The novelty of this manuscript is that the strategy of using the variance of the tracking errors to improve the LSQ stochastic model is tested for the first time in PPP processing and the results show the ability of this strategy to successfully mitigate the effects of strong scintillation frequently encountered in the low latitudes of Brazil. The data and methodology are described in Sect. 2, along with the proposed LSQ stochastic model for GNSS positioning and details of the PPP processing software used to evaluate the proposed scintillation mitigation approach. Results are presented and discussed in Sect. 3. Section 4 presents the conclusions.

2 Data and methodology

This study analyses data collected during 14–16 March 2015 by Septentrio PolaRxS ionospheric scintillation monitoring receivers (ISMR) operational at stations Presidente Prudente (PRU2) and Sao Jose dos Campos (SJCU) in Brazil. The geographic coordinates of the stations and their corresponding geomagnetic latitudes are listed in Table 1. It is clear from Table 1 that PRU2 and SJCU are located close to the southern EIA crest in the South American sector, where strong and frequent scintillation occurs during the March equinox month.

The PolaRxS receiver generates and stores raw high rate signal data at 50 Hz in hourly files, which are processed to give one minute amplitude and phase scintillation indices, along with other parameters like TEC, and the scintillation spectral parameters, p and T, for all visible satellites and frequencies. Ionospheric scintillation levels are usually quantified by the two widely recognised indices, namely the amplitude scintillation index, S4 and the phase scintillation index, σφ. The S4 is defined as the standard deviation of the received 50 Hz raw signal power normalised by its mean value, while σφ is defined as the standard deviation of the 50 Hz detrended carrier phase using a high pass Butterworth filter with 0.1 Hz cut-off computed over 60 s (Van Dierendonck 2001). Scintillation levels are defined using the S4 index, namely as, weak (0.3 ≤ S4 < 0.4), moderate (0.4 ≤ S4 < 0.7) and strong (S4 ≥ 0.7). The raw 50 Hz data recorded by the receiver contain the carrier phase (in cycles) and the post-correlation In-Phase (I) and Quadra-phase (Q) components, which can be used to estimate the S4, σφ, p and T at shorter time intervals.

The PPP approach described in Zumberge et al. (1997), as implemented in the so-called RT-PPP software (Marques et al. 2016), was used for processing the data. This software was chosen because of its capability to read an external input file with tracking error variances for every epoch and satellite, thus allowing to test the scintillation mitigation approach. The GPS dual-frequency L1C/A and L2P data were processed in a kinematic mode considering a satellite elevation mask of 10°, final precise orbits and clocks from the International GNSS Service (IGS) and the tropospheric delay estimated as a random walk process with a precision of \( 5{\mathrm{mm/}}\sqrt {\mathrm{h}} \). The ionospheric-free linear combination was applied for processing both code and phase observables, thus eliminating the first-order ionospheric effects. Additional models/corrections, namely corrections for receiver and satellite phase center variation (PCV), Earth body tides (EBT), ocean tides loading (OTL), differential code biases (DCBs), phase windup and relativistic effects, were also applied. When in the kinematic mode, the RT-PPP software estimates the coordinates at every epoch, but the ambiguities are estimated in a cumulative way via recursive LSQ adjustment and treated as a random constant process (Teunissen 2001). The adjustment quality control is based on the detection, identification and adaptation (DIA) method (Teunissen 1998). The PPP ambiguity convergence period depends on a set of factors including the number of available satellites, satellite geometry and the effect of un-modelled atmospheric errors such as ionospheric scintillation. Under strong scintillation conditions, a large number of cycle slips and even total losses of lock are observed, resulting in a smaller number of available observations, and leading to an ambiguity reinitialization in the recursive adjustment, causing jumps in the positioning time series and increasing the PPP convergence period. In the absence of scintillation, with this configuration an accuracy at the level of a few cms is expected in the estimated 3D position components after the initial convergence period of about 20 min.

The stochastic model of GNSS observables in the LSQ adjustment is usually based either on a constant standard deviation per observable type, referred to as ‘constant’ weighting, or on a standard deviation scaled as a function of the satellite elevation angle, referred to as ‘elevation’ weighting. In the RT-PPP software, the standard deviation of each undifferenced observable for the constant weighting was adopted as: σL1C/A = 0.8 m, σL2P = 1 m, σφ1 = 0.008 m and σφ2 = 0.010 m, respectively, for L1C/A and L2P pseudoranges and carrier phases, which are then propagated for the ionospheric-free combination. The standard deviation for the elevation weighting is based on the inverse sine of the satellite elevation angle. In addition to these two weighting approaches, following the approach of Aquino et al. (2009), the LSQ stochastic model in the RT-PPP software was modified by using the tracking error variance calculated per epoch for each satellite/receiver link. This variance was calculated using the receiver tracking models proposed in Conker et al. (2003), referred to as the Conker model, and in Moraes et al. (2014), referred to as the α–μ model. The Conker models are limited to weak-to-moderate levels of scintillation, i.e. S4(L1) < 0.707, and hence cannot be applied for all levels of scintillation, even if the receiver does not lose lock. This is particularly relevant for the equatorial/low latitudes, where very strong scintillation conditions are frequently encountered, with S4(L1) reaching over 0.8. The limitation of the Conker models relates to the fact that they rely on the commonly adopted assumption that the distribution of amplitude scintillation is best characterised by the Nakagami-m Probability Distribution Function (PDF) (Nakagami 1960). Moraes et al. (2014) introduced models to estimate the GPS tracking error variances based on the α–μ distribution of Yacoub (2007). The tracking error models based on α–μ distribution are indeed extended models that turns into the Conker models when α = 2 and μ = m. These extended models thus allows the computation of the tracking error variances for a wider set of scintillation regimes, depending on the α value, including under strong amplitude scintillation, i.e. when S4 > 0.7. According to Moraes et al. (2013), the α–µ PDF of the normalised amplitude envelope r is given by:

Γ(.) is the gamma function and ξ is estimated from the α and μ coefficients using the following equation:

The pair of – coefficients may be estimated from the received signal based on the following equality (Yacoub 2007):

The top three panels of Fig. 1 exemplify three cases of scintillation data with S4 ≈ 0.9. Despite the very close S4 values, it is possible to observe that the scintillation pattern is significantly different from one another in all the three cases. The bottom three panels of Fig. 1 show the respective empirical distribution in circles based on the cases shown in the top panels. For comparison purposes, these panels also show the α–μ distribution curves in solid lines, as well as the Nakagami-m curves in dashed grey.

(Top panels) Three amplitude scintillation cases with S4 ≈ 0.9. (Bottom panels) Respective theoretical α–μ probability density curves in solid line with the α–μ pair estimated based on Eq. (3) and the Nakagami-m distribution curves in grey dashed line

It can be noted from Fig. 1 that differences between the empirical distributions of the three cases are well captured by the α–μ model while the single parameter-based Nakagami-m model generates the same curve for all the three cases. Furthermore, it can be observed that for the same S4 as the value of α increases, the tail of the distribution tends to rise, suggesting that fading events are most likely to occur. Details about the typical values of the fading coefficients and its variations according to the propagation path can be found in Moraes et al. (2018a, b).

The scintillation mitigation algorithms presented in this manuscript are based on the estimation of the receiver PLL and DLL tracking error variances, which are in turn used, respectively, to calculate the weights for the different carrier phase and pseudorange observables. The Conker and α-μ models provide variances for the following observables, namely PL1C/A, PL2P, φL1C/A and φL2P and require as input scintillation-related parameters as well as receiver-specific parameters. A brief description of the Conker and α–μ models is provided here and for further details, the reader is referred to Conker et al. (2003) and Moraes et al. (2014). The Conker model for the L1C/A DLL and PLL tracking error variance in code chips squared and radians squared is, respectively, given by:

where BnDLL is the one-sided noise bandwidth, equal to 0.25 Hz; BnPLL is the third-order PLL one-sided bandwidth, equal to 15 Hz; d is the correlator spacing, equal to 0.04 C/A chips; (c/n0)L1–C/A is the fractional form of signal-to-noise density ratio, equal to \(10^{{0.1\left( {C/N0} \right)_{{{\mathrm{L}}1 - {\mathrm{C}}/{\mathrm{A}}}} }} \); ηDLL is the DLL predetection integration time, equal to 0.1 s; ηPLL is the PLL predetection integration time, equal to 0.01 s; S4(L1) is the amplitude scintillation index on L1C/A; T is the spectral strength of the phase noise at 1 Hz, p is the spectral slope of the phase power spectral density (PSD), k is the order of the PLL loop equal to 3 and fn is the loop natural frequency equal to 3.04 Hz.

The α–μ model for the L1C/A DLL and PLL tracking error variances is given by:

where BnDLL, BnPLL, d, (c/n0)L1−C/A, \( \eta_{\mathrm{DLL}} \), \( \eta_{\mathrm{PLL}} \), T, p, k and fn denote and have the same values as in Eqs. (4) and (5). The input scintillation parameters such as S4(L1), T, p, α and μ for the Conker and α–μ models are estimated from the receiver recorded raw 50 Hz data. The signal-to-noise density (C/N0) values recorded by the receiver for GPS L1C/A and L2P signals are used to estimate the fractional form of C/N0 used in the models. The receiver input parameters such as receiver loop natural frequency, predetection integration time of both DLL and PLL and order and bandwidth of both DLL and PLL tracking loops are known from the receiver configuration.

3 Results and discussion

The one minute scintillation indices, S4 (black dots) and σφ (red dots) values, recorded on the GPS L1C/A signal by the PolaRxS receiver at PRU2 (top panel) and SJCU (bottom panel) during 14–16 March 2015 is shown in Fig. 2. A satellite elevation angle cut-off of 20° has been applied while generating this figure in order to remove the contribution from non-scintillation-related effects, such as multipath.

It can be observed from Fig. 2 that over PRU2 and SJCU, scintillation occurs during 00:00–04:00 UT, corresponding to 21:00–01:00 local time, thus highlighting the well-known fact that low latitude scintillation is essentially a post-sunset phenomenon (Basu et al. 2002). The day-to-day variability in scintillation occurrence is also clearly observed from this figure.

Figure 3 shows the total number of visible and scintillation-affected GPS satellites with an elevation angle greater than 20° at PRU2 (top panel) and SJCU (bottom panel) during 14–16 March. As during strong scintillation, there is a higher probability of losing the satellite signal lock resulting in degraded positioning accuracy, a threshold of 0.7 for S4 and σφ is applied to check for the number of satellites affected by scintillation.

From Fig. 3, it can be observed that the total number of visible satellites (shown by blue lines) follows a similar pattern on the 3 days at PRU2 and SJCU. During 00:00–04:00 UT at PRU2, only 1 satellite is observed to meet the strong scintillation threshold on 14 March, whereas on 15 and 16 March, the number of strong scintillation-affected satellites could be as large as 3 and 4, respectively. This suggests that there could be significant degradation in the positioning accuracy on these 2 days. On the other hand, at SJCU the number of strong scintillation-affected satellites is only 1 or 2 on all the 3 days, suggesting that the degradation in the positioning accuracy will not be as significant when compared to PRU2.

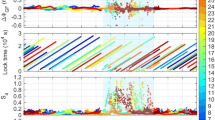

To compare the variances between non-scintillation and scintillation-affected satellites, the variations in S4 (top panels), DLL (middle panels) and PLL tracking error variances (bottom panels) on GPS L1C/A signal at PRU2 on 16 March 2015 is shown in Fig. 4. The non-scintillation and scintillation-affected satellites are shown by red and black lines, respectively. The DLL and PLL tracking error variances have been estimated, respectively, using Eqs. (6) and (7).

It can be observed from Fig. 4 that the PLL and DLL tracking error variances increase with the increase in the S4 values, thus suggesting that the tracking error variances are sensitive to the scintillation effects. The values of the DLL and PLL tracking error variances in general vary between 0–0.15 m2 and 0.01–0.05 rad2, respectively. For the scintillation-affected satellites, namely SV01 and SV23, the DLL and PLL tracking error variances show enhancement with the increase in S4, whereas for the non-scintillation satellites SV03 and SV10, no such enhancement is observed. The approach of excluding the scintillation-affected satellites with higher values of tracking error variances out of the PPP processing will not work, as most of the satellites involved are affected by strong levels of scintillation as can be observed from the top panel of Fig. 3. This illustrates the fact that arbitrarily excluding scintillation-affected satellite(s) may not be the best approach for kinematic PPP over low latitudes under strong scintillation conditions.

To analyse the effect of scintillation on positioning performance, a time window in the period of 18:00–03:00 local time was chosen, which corresponds to 21:00–06:00 UT. This time window was chosen because it covers a period of no scintillation followed by significant higher levels affecting one or more satellites simultaneously, thus allowing the PPP solution to converge before the occurrence of scintillation. The epoch by epoch kinematic PPP processing results on 14 (left panel), 15 (middle panel) and 16 March (right panel) at PRU2 is shown in Fig. 5. The positioning errors in the height (dU) and the horizontal components (2D) for the different weighting approaches, namely ‘Constant’, ‘Elevation’, ‘Conker’ and ‘α–μ’, are shown accordingly, by black, magenta, red and blue lines.

Epoch by epoch kinematic PPP processing results obtained at PRU2 during 21-06 UT on 13–14 (left panel), 14–15 (middle panel) and 15–16 March (right panel). The positioning accuracy is represented by the error in the height (top rows) and 2D (bottom rows). The different weighting approaches are shown by black (Constant), magenta (Elevation), red (Conker) and blue (α-μ) lines

From Fig. 5, it is observed that the PPP solution has a convergence time of around 30 min for all the weighting approaches. The impact of strong scintillation during 00:00–04:00 UT on 15 and 16 March at PRU2, as shown by the rectangle, on the positioning solution is very evident from this figure. As scintillation can cause carrier loss of lock and cycle slips, during the period of strong scintillation, the tracking error variance-based weighting approaches, namely ‘Conker’ and ‘α–μ’, give the best positioning solutions, both for the height and the horizontal components. A summary of the results comparing the different approaches at PRU2 and SJCU on 14, 15 and 16 March is shown in Tables 2 and 3, respectively. The tables show the RMS values of the height (dU), 2D and 3D positioning errors during the period of strong scintillation, defined as 00:00–04:00 UT at PRU2 and SJCU.

Table 2 illustrates that on 14 March at PRU2 when weak scintillation was observed (refer Figs. 2 and 3), all the weighting approaches provide comparable results, with overall 3D RMS of less than 10 cm. Under strong scintillation on 15 and 16 March, the Conker and α–μ approaches provide the best results, with significant improvement in the 3D RMS of around 73–75% on 15 March and 62–69% on 16 March, against the ‘constant’ approach. With respect to the elevation-based weighting approach, the Conker and α-μ approaches provide improvement of around 17–26% on 15 March and 20–34% on 16 March. The elevation approach also provides encouraging results on 15 March, with 3D RMS of around 12 cm.

On comparing Tables 2 and 3, it is clear that on all the 3 days, the positioning accuracy at SJCU is much better than that obtained over PRU2, which could be attributed to the occurrence of weak scintillation (refer Figs. 2 and 3) at SJCU. The Conker and α–μ approaches provide improvement of around 4–6% on 14 March, 16–17% on 15 March and 58% on 16 March with respect to the ‘constant’ approach. The overall 3D RMS obtained with the Conker and α–μ approaches is less than 10 cm on all the 3 days. As the scintillation was weak over SJCU, the elevation approach is also providing 3D RMS comparable to that of the Conker and α–μ approaches.

The above results indicate that the proposed scintillation mitigation technique based on improving the LSQ stochastic model by using the tracking error variances can help achieve the required real-time PPP accuracy under strong scintillation conditions at low latitudes. It is recognised that further research is necessary to overcome the limitations of this proposed technique based on scintillation parameters output by specialised receivers. In future, it is planned to exploit the statistical models, presented in Vadakke Veettil et al. (2018), based on the RMS of the Rate of change of slant TEC, ROTrms to estimate the PLL tracking error variance for a conventional receiver, in an attempt to generalise this technique for any type of receiver. It is also to be noted that the obtained high accuracy results are based on the GPS legacy signals, L1C/A and L2P. The inclusion of modernised Galileo E1 and E5 Altboc signals, with improved signal structure, could help achieve better results and will also be the focus of future research.

4 Conclusions

A technique to mitigate the effects of ionospheric scintillation on PPP, which is the most critical effect degrading high accuracy positioning performance, is presented. The proposed scintillation mitigation technique is based on the estimation of the receiver tracking error variances, which are in turn used to improve the LSQ stochastic model used in position computation. The performance of the technique is demonstrated by using data recorded by specialised receivers at low latitude stations of PRU2 and SJCU in Brazil. The results indicate that the proposed technique can help achieve the required PPP accuracy under strong scintillation conditions, with improvement in the 3D positioning accuracy of around 62–75% at PRU2. The significance of the results lies in the improvement of this technique which can offer in support to GNSS high accuracy applications under unfavourable scintillation conditions.

Data availability

The datasets analysed in this study are managed by the Faculty of Science and Technology (FCT), UNESP - Univ Estadual Paulista, Presidente Prudente, São Paulo State, Brazil and can be made available by the corresponding author on request.

References

Aquino M, Monico JFG, Dodson AH, Marques H, De Franceschi G, Alfonsi L, Romano V, Andreotti M (2009) Improving the GNSS positioning stochastic model in the presence of ionospheric scintillation. J Geod 83:953–966. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00190-009-0313-6

Basu S, Groves KM, Basu Su, Sultan PJ (2002) Specification and forecasting of scintillations in communication/navigation links: current status and future plans. J Atmos Solar-Terr Phys 64(16):1745–1754. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1364-6826(02)00124-4

Conker RS, El Arini MB, Hegarty CJ, Hsiao T (2003) Modeling the effects of ionospheric scintillation on GPS/SBAS availability. Radio Sci. https://doi.org/10.1029/2000RS002604

Doherty PH, Delay SH, Valladares CE, Klobuchar JA (2003) Ionospheric scintillation effects on GPS in the equatorial and auroral regions. Navigation 50:235–245. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-4296.2003.tb00332.x

Dubey S, Wahi R, Gwal AK (2006) Ionospheric effects on GPS positioning. Adv Sp Res 38(11):2478–2484. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asr.2005.07.030

Groves KM, Basu S, Quinn JM, Pedersen TR, Falinski K, Brown A, Silva R, Ning P (2000) A comparison of GPS performance in a scintillating environment at Ascension Island. In: Proceedings of ION GPS 2000, Institute of Navigation, Salt Lake City, UT, September 2000, pp 72–679

Humphreys T (2005) GPS carrier tracking loop performance in the presence of ionospheric scintillations. In: Proceedings of ION GNSS 2005, Institute of Navigation, Long Beach, CA, September 2005, pp 156–167

Ji S, Chen W, Wang Z, Xu Y et al (2013) A study of occurrence characteristics of plasma bubbles over Hong Kong area. Adv Sp Res 52(11):1949–1958. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asr.2013.08.026

Luo X, Lou Y, Xiao Q, Gu S, Chen B, Liu Z (2018) Investigation of ionospheric scintillation effects on BDS precise point positioning at low-latitude regions. GPS Solut 22:63. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10291-018-0728-8

Marques HAS, Monico JFG, Marques HA (2016) Performance of the L2C civil GPS signal under various ionospheric scintillation effects. GPS Solut 20(2):139–149. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10291-015-0472-2

Marques HA, Marques HAS, Aquino M, Vadakke Veettil S, Monico JFG (2018) Accuracy assessment of precise point positioning with multi-constellation GNSS data under ionospheric scintillation effects. J Sp Weather Sp Clim. https://doi.org/10.1051/swsc/2017043

Moraes AO, de Paula ER, Perrella WJ, Rodrigues FS (2013) On the distribution of GPS signal amplitudes during low-latitude ionospheric scintillation. GPS Solut 17:499. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10291-012-0295-3

Moraes A, Costa E, de Paula E, Perella W, Monico J (2014) Extended ionospheric amplitude scintillation model for GPS receivers. Radio Sci. https://doi.org/10.1002/2013RS005307

Moraes AO, Vani BC, Costa E et al (2018a) GPS availability and positioning issues when the signal paths are aligned with ionospheric plasma bubbles. GPS Solut 22:95. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10291-018-0760-8

Moraes AO, Vani BC, Costa E, Sousasantos J, Abdu MA, Rodrigues F et al (2018b) Ionospheric scintillation fading coefficients for the GPS L1, L2, and L5 frequencies. Radio Sci 53:1165–1174. https://doi.org/10.1029/2018RS006653

Moreno B, Radicella S, de Lacy MC, Herraiz M, Rodriguez-Caderot G (2011) On the effects of the ionospheric disturbances on precise point positioning at equatorial latitudes. GPS Solut 15(4):381–390. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10291-010-0197-1

Muella MTAH, de Paula ER, Monteiro AA (2013) Ionospheric scintillation and dynamics of Fresnel-scale irregularities in the inner region of the equatorial ionization anomaly. Surv Geophys 34:233–251. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10712-012-9212-0

Nakagami M (1960) The m-distribution: a general formula of intensity distribution of rapid fading. In: Hoffman WC (ed) Statistical methods in radio wave propagation. Pergamon, New York, pp 33–36

Park J, Veettil SV, Aquino M, Yang L, Cesaroni C (2017) Mitigation of ionospheric effects on GNSS positioning at low latitudes. J Inst Navig 64:67–74. https://doi.org/10.1002/navi.177

Silva HA, Camargo PO, Monico JFG, Aquino M, Marques HA, De Franceschi G, Dodson A (2010) Stochastic modelling considering ionospheric scintillation effects on GNSS relative and point positioning. Adv Sp Res 45:1113–1121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asr.2009.10.009

Skone S, Shrestha SM (2002) Limitations in DGPS positioning accuracies at low latitudes during solar maximum. Geophys Res Lett. https://doi.org/10.1029/2001gl013854

Skone S, Kundsen K, de Jong M (2001) Limitation in GPS receiver tracking performance under ionospheric scintillation conditions. Phys Chem Earth (A) 26:613–621. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1464-1895(01)00110-7

Sreeja V, Aquino M, Elmas ZG, Forte B (2012) Correlation analysis between ionospheric scintillation levels and receiver tracking performance. Sp Weather. https://doi.org/10.1029/2012sw000769

Susi M, Andreotti M, Aquino M, Dodson A (2017) Tuning a Kalman filter carrier tracking algorithm in the presence of ionospheric scintillation. GPS Solut. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10291-016-0597-y

Teunissen PJG (1998) Quality control and GPS. In: Teunissen PJG, Kleusberg A (eds) A GPS for geodesy, 2nd edn. Springer, Berlin, pp 271–318

Teunissen PJG (2001) Dynamic data processing: recursive least squares. Delft University Press, Delft

Vadakke Veettil S, Aquino M, Spogli L Cesaroni C (2018) A statistical approach to estimate Global Navigation Satellite Systems (GNSS) receiver signal tracking performance in the presence of ionospheric scintillation. J Space Weather Space Clim 8(A51). https://doi.org/10.1051/swsc/2018037

Van Dierendonck, A J (2001) Measuring ionospheric scintillation effects from GPS signals. In: Proceedings of 57th annual meeting of the Institute of Navigation, Albuquerque, New Mexico, pp 391–396

Vani BC, Forte B, Monico JFG, Skone S, Shimabukuro MH, Moraes AO, Portella IP, Marques HA (2019) A novel approach to improve GNSS Precise Point Positioning during strong ionospheric scintillation: theory and demonstration. IEEE Trans Veh Technol 68:4391–4403. https://doi.org/10.1109/TVT.2019.2903988

Weng D, Ji S, Chen W, Liu Z (2014) Assessment and mitigation of ionospheric disturbance effects on GPS accuracy and integrity. J Navig 67:371–384. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0373463314000046

Xu R, Liu Z, Li M, Morton Y, Chen W (2012) An analysis of low-latitude ionospheric scintillation and its effects on precise point positioning. J Glob Pos Syst 11:22–32. https://doi.org/10.5081/jgps.11.1.22

Xu R, Liu Z, Chen W (2015) Improved FLL-assisted PLL with in-phase pre-filtering to mitigate amplitude scintillation effects. GPS Solut 19:263. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10291-014-0385-5

Yacoub MD (2007) The α–μ distribution: a physical fading model for the Stacy distribution. IEEE Trans Veh Technol 56:24–27. https://doi.org/10.1109/TVT.2006.883753

Zhang L, Morton Y (2009) Tracking GPS signals under ionosphere scintillation conditions. In: Proceedings of ION-GNSS-2009, Institute of Navigation, Savannah, GA, USA, September 2009, pp 227–234

Zhang X, Guo F, Zhou P (2014) Improved precise point positioning in the presence of ionospheric scintillation. GPS Solut 18:51–60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10291-012-0309-1

Zumberge JF, Heflin MB, Jefferson DC, Watkins MM, Webb FH (1997) Precise point positioning for the efficient and robust analysis of GPS data from large networks. J Geophys Res Solid Earth 102:5005–5017. https://doi.org/10.1029/96JB03860

Acknowledgements

Data from the PRU2 and SJCU stations in Brazil are part of the CIGALA/CALIBRA network. Monitoring stations from this network were deployed in the context of the Projects CIGALA and CALIBRA, both funded by the European Commission in the framework of the FP7-GALILEO-2009-GSA and FP7–GALILEO–2011–GSA–1a, respectively, and FAPESP Project Number 06/04008-2. A. O. Moraes is supported by CNPq 314043/2018-7 and collaborated in this work through the framework of the INCT GNSS-NavAer Project CNPq 465648/2014-2 and FAPESP 2017/01150-0.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SVV and MA initiated the study, HM and AM provided the software for analysis, SVV analysed the data and wrote the manuscript. All authors provided critical feedback and helped to shape the analysis and manuscript.

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Vadakke Veettil, S., Aquino, M., Marques, H.A. et al. Mitigation of ionospheric scintillation effects on GNSS precise point positioning (PPP) at low latitudes. J Geod 94, 15 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00190-020-01345-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00190-020-01345-z