Abstract

This study empirically examines the role of enterprise risk management (ERM) in developing and maintaining resilience resources and capabilities that are necessary for an organisation’s strategic transformation towards sustainability. Data was collected through 25 semi-structured interviews, one non-participant observation, and secondary sources in the context of a Swedish mining company undergoing a high-risk strategic transformation towards full decarbonisation. Following the temporal bracketing approach (Langley in Academy of Management Review 24:691–70, 1999) and employing thematic analysis (Gioia in Organizational Research Methods 16:15–31), the data was structured and analysed according to three phases from 2012 to 2023. The findings show: first, different ERM practices, such as risk governance frameworks, risk culture, risk artefacts, and risk awareness, influence resilience resources and capabilities. Second, the evolution of risk management practices from traditional risk management to ERM is an ongoing developmental process to ensure that risk management continues to be aligned with the company’s strategy. Third, in tandem with strategic changes, resilience in terms of resources and capabilities emerges over time and develops through a series of events, gradually enhancing the company’s ability to manage risks and uncertainties associated with multidimensional sustainability challenges. These results contribute to the ERM literature that follows the dynamic capability approach and also focuses on the relationship between ERM and strategy by adding more detailed empirical evidence from the risk management literature in relation to resilience resources and capabilities. Additionally, the results contribute to the resilience literature that follows a developmental perspective.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The steel industry is responsible for approximately 5% of CO2 emissions in the EU and 7% globally (Somers, 2022). While facing environmental, social, economic, and political challenges, companies operating in this strategic sector need to accelerate the decarbonisation processes to meet the EU’s ambitions for 2030 and the climate targets for 2050 (McKinsey, 2020). Therefore, a transformational change towards decarbonisation is essential for the long-term survival of mining, iron, and steel companies. If companies fail to achieve sustainable operations, their value-creating capacity, as well as their operating licence, which is critical to their business continuity, will be threatened. The necessity of the transformational change towards decarbonisation has prompted some of the Swedish iron and steel companiesFootnote 1 to take the lead in [re]formulating their strategies towards more sustainable business models, adapting to an increasingly challenging business environment, and raising global awareness concerning sustainability-related issues.

However, as a part of the transformational process towards implementing sustainable strategies, companies face sustainability-related risks that have some characteristics of novel risksFootnote 2 in terms of being unexpected, and thus traditional risk management would be ineffective in handling these types of risks (Kaplan et al., 2020). Therefore, companies need to invest in their capabilities (Kaplan et al., 2020) and activate, combine, and reconfigure their resources to be able to respond to uncertainties and create value (Andersen et al., 2022). In this regard, enterprise risk management (ERM), which “constitutes a dynamic capability” (Nair et al., 2014, p. 558), can support companies in avoiding undesirable events, minimising losses, and most importantly, finding creative answers to disruptions (Bogodistov & Wohlgemuth, 2017). Nonetheless, striking a balance between short-term efficiency and long-term development can be challenging in practice (Andersson et al., 2019).

Some studies implicitly show ERM enables companies to employ various resources that can contribute to a company’s resilience capacity. For instance, Lundqvist (2015) claims that ERM includes risk governance frameworks that establish a structured approach to the management of risks by defining risk responsibilities within the organisation. ERM also includes designing and using risk artefacts to promote risk communication (Klein & Reilley, 2021), integrating risk information into strategic decision-making (Giovannoni et al., 2016), and sharing risk information across the organisation (Arnold et al., 2011), all of which eventually lead to increased risk awareness in an organisation (Braumann, 2018). The findings of these studies are in line with the three categories of resilience resources proposed by (Richtnér & Södergren, 2008), namely structural, relational, and cognitive resources (see Table 1). However, there is a scarcity of studies that explicitly explain how ERM, as dynamic capability, influences a company’s resilience resources and resilience capabilities in the context of strategic change. This could be due to the fact that ERM as a concept remains obscure (Bromiley et al., 2015), as does resilience (Andersson et al., 2019; Linnenluecke, 2017). Furthermore, considering the complexity of sustainability challenges, the lack of integration of resilience thinking into risk assessment practices and the ERM literature may further contribute to the ambiguity surrounding the relationship between risk management and resilience (Wassénius & Crona, 2022). A more integrated understanding of risk management, that includes resilience thinking, could help in overcoming the limitations of traditional risk management approaches in particular, when dealing with uncertainty.

In the context of a Swedish mining company undergoing a high-risk transformational strategic change, this study aims to empirically examine the role of ERM in developing and maintaining resilience capabilities in daily practice and over time (Andersson et al., 2019). We do so in order to understand how risk management practices can evolve and not only help organisations avoid undesirable events and "bounce back" when they occur, but also "bounce forward" (Jaeger, 2010) by discovering new creative solutions (Richtnér & Löfsten, 2014) in situations characterised by high levels of environmental complexity. This aim leads to the following research question:

RQ

How does ERM contribute to developing and maintaining the resilience necessary for the strategic transformation of an organisation towards sustainability?

We answer the research question by conducting a single case study at one of the mining companies currently involved in the decarbonisation project in Sweden where we gathered data via 25 semi-structured interviews, a non-participant observation, and secondary sources.

This study makes the following contributions to the literature. First, it contributes to our understanding of how ERM can be perceived as a dynamic capability (Andersen et al., 2022; Bogodistov & Wohlgemuth, 2017; Nair et al., 2014) by showing how various elements of ERM, such as risk governance frameworks, risk culture, risk artefacts, and risk awareness, influence resilience capacity-derived resources and action-derived capabilities. Second, this study contributes to our understanding of the relationship between ERM and strategy (Sax & Andersen, 2019), by showing that the evolution of risk management practices from traditional risk management to ERM is an ongoing developmental process to ensure that risk management continues to be aligned with the organisation’s strategy. Third, by drawing on the resilience literature that follows a developmental perspective (Richtnér & Södergren, 2008; Sutcliffe & Vogus, 2003) we find that in tandem with strategic changes, resilience in terms of resources and capabilities, emerged overtime and developed through a series of events, gradually enhancing the company’s ability to manage risk and uncertainties associated with sustainability challenges that are complex and multidimensional (Wassénius & Crona, 2022). Additionally, following the resilience literature (i.e., Van der Vegt et al., 2015), our findings also show that capacity-derived resources and action-derived capabilities have dynamic relationships between and across their domains.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2 reviews the literature on enterprise risk management, resilience and also presents the theoretical coordinates that guides this research. Section 3, provides an overview of the research methods. The empirical findings are presented in Sect. 4, followed by a discussion in Sect. 5. Finally, the conclusions and contributions are presented in Sect. 6.

2 Literature review and theoretical coordinates

This section begins with a review of the literature on risk management, with a specific focus on understanding how enterprise risk management is increasingly being recognised as an enabler of organisational resilience. In doing so, we first outline the main attributes of ERM and differences between ERM and traditional risk management. Thereafter, we examine the relationship between ERM, strategy, and sustainability prior to analysing how resources and capabilities are presented in the ERM literature. Finally, we take a closer look at the resilience concept, its origins, and interpretations, and end the section with a presentation of the theoretical coordinates that are used in the analysis of the empirical case.

2.1 Enterprise risk management

ERM has emerged as a leading paradigm for good corporate governance and risk management globally (Anton & Nucu, 2020). It is supported by regulators and rating agencies and requires the alignment of traditional risk management (TRM) with risk governance and strategy. The concept of ERM lacks a universally accepted definition, and evidence from empirical studies shows that it does not manifest in a standardised format when implemented in practice (Mikes & Kaplan, 2015). However, based on an extensive review of the literature, Bromiley et al. (2015) point out that there is an emerging consensus that ERM has three core attributes. 1. “ERM assumes that managing the risk of a portfolio (the corporation) is more efficient than managing the risks of each of the individual subsidiaries (parts of the corporation or activities).” 2. “ERM incorporates not only traditional risks like product liability and accidents, but also strategic risks…” 3. “ERM assumes firms should not look at risk as a problem to mitigate. Firms with a capability for managing a particular risk should seek competitive advantage from it.” (Bromiley et al., 2015, p. 268).

In contrast to ERM, TRM is conceptualised as a process which according to Lundqvist (2015, p. 442) “entails individually or in a silo identifying risk, measuring risk, monitoring, and perhaps reporting on risk but with little formality, structure, or centralization; simple examples being an isolated group of individuals in the finance department hedging currency risk or a factory floor manager tracking incidents of injury on the job”. Hence, ERM signifies a more comprehensive approach to risk management in comparison to TRM and it is widely accepted in the literature that ERM adoption enables organisations to employ a wider variety of risk management strategies. These may include the use of insurance and derivatives for risk transfer and financial risk management; the inclusion of scenario analysis to forecast emerging risks; and the appointment of chief risk officers (CRO) to promote risk culture and enhanced risk awareness (Braumann, 2018; Mikes, 2009). In other words, ERM may enable organisations to identify the need to reconfigure resources and capabilities which are necessary when attempting to respond to increasingly complex, ambiguous, and rapidly evolving environments (Nair et al., 2014).

ERM has taken on a new emphasis in light of recent failures to manage strategic risks, including regulatory and compliance risks, competitor risks, economic risks, political risks, technology risks, and partnership and/or collaboration risks (Dhlamini, 2022, pp. 2–3). Organisations, especially those that undergo a strategic transformation, are exposed to novel and strategically significant risks that are difficult to anticipate and quantify. While the literature suggests that an increasing number of organisations engage in some form of risk envisionment which according to Mikes (2011, p. 235) is “an alternative style of risk control which does not privilege risk measurement over judgement and soft instrumentation”, Kaplan et al. (2020, p. 42) remind us that even if that is the case, organisations may still not be willing to “invest in the capabilities and resources to cope with them [novel risks] because they seem so unlikely.” In such instances, the value-creating potential of ERM (see Baxter et al., 2013; Jabbour & Abdel-Kader, 2016) may be inhibited. One possible explanation for this is that the link between ERM and strategic planning has not been formalised in a manner that leads to the establishment of practices to identify, mitigate, and manage strategic risks and opportunities and, in turn, increase organisational risk awareness (Sax & Andersen, 2019).

The relationship between ERM and sustainability has become a central topic for practitioners in light of the transition to a low-carbon economy and the strategic challenges this transition poses (WBCSD, 2016). ERM has also been discussed in the literature in terms of its potential contribution to sustainable decision-making (Liu, 2019) and its integration with sustainability reporting to enhance business performance (Shad et al., 2019). In essence, sustainability, according to Antoncic (2019, p. 208), “is the latest evolutionary development on the very same continuum of risk management we have watched unfold for decades.” Sustainability-related risks exhibit many of the characteristics of novel risks in terms of being difficult to imagine and quantify. They can arise from distance events, e.g., at a supplier, through the development and introduction of new and more complex products which are derived from new ideas, features, systems and technologies, or from a rare event e.g., plant damage emerging from an earthquake (Antoncic, 2019). Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that integrating sustainability risks into the ERM process will require the type of investments in resources and capabilities outlined by Kaplan et al. (2020).

Drawing on the existing literature, we argue that in order for an organisation to effectively use ERM to develop and maintain resilience, it needs to recognise the strategic value-creating capabilities of ERM. These capabilities should extend beyond compliance with external requirements, such as regulations for the purpose of establishing legitimacy (Power, 2009). Nevertheless, it is important to recognise that compliance-type processes, e.g., risk control, disaster recovery plans, and business continuity planning, can have a significant and positive impact on resilience if applied quickly in times of crises (Bhamra et al., 2011). Furthermore, it is important that sustainability risks are integrated into the organisation’s ERM framework to enable their assessment and management from a more strategic perspective (Antoncic, 2019; Wassénius & Crona, 2022). Through this approach, the literature suggests that ERM can be perceived as a dynamic capability when resources and capabilities are configured in such a way as to enable organisations to identify and act upon opportunities that emerge in situations of rapid environmental change and turbulent and uncertain business contexts (Andersen et al., 2022). In detailing how, resources and capabilities are configured Andersen et al. (2022, p. 4) state that “the resources are combined in unique ways and deployed by the firm through different capabilities to generate specific types of valuable output, e.g., products, services, and organisational processes.” In addition, they suggest that the effectiveness of dynamic capabilities is contingent on, the organisational structure, e.g., the establishment of standardised routines and processes; on non-routine strategizing and entrepreneurial activities, e.g., in groups or networks; and managerial cognition, e.g., idea generation, learning, and sensing. The resources and capabilities described above closely reflect the resources proposed by Richtnér and Södergren (2008) and the capabilities put forward by Jaeger (2010) (see Table 1).

2.1.1 ERM as a dynamic capability: Insights from the literature

Taking the departure point that, “the overlapping attributes of ERM and dynamic capabilities strongly point to the conclusion that ERM constitutes a dynamic capability”, (Nair et al., 2014, p. 558); that by definition dynamic capabilities are “a firm’s ability to integrate, build, and reconfigure internal and external competencies to address rapidly changing environments” (Nair et al., 2014, citing Teece et al., 1997, p. 516); and that a dynamic capability perspective supports organisations in moving beyond the ex-ante prediction of risky events e.g., in compliance and due diligence processes, to providing managers with the tools to recover from risky events that may occur (Bogodistov & Wohlgemuth, 2017), we turn to empirical studies for further insights how those resources and capabilities may emerge in the context of ERM in practice.

The transition from TRM to ERM, according to Zhivitskaya and Power (2016), redirects the emphasis of organisations from developing robust formal processes that are independent from the business and adhere to policy objectives, to developing and deploying competences that serve the needs of the board and executive management. The risk governance framework, which establishes a formalised and structured approach to the management of risk with clear lines of responsibility and accountability, as well as the role and mandate of the chief risk officer (CRO) and the risk function within the overall organisational structure (Lundqvist, 2015) is a foundational element in enabling ERM as a dynamic capability. Risk governance can be a source of competitive advantage, and it determines to what extent ERM will be integrated into strategic planning and other control processes (Lundqvist, 2015; Sax & Andersen, 2019). Boholm et al. (2012) further emphasise the importance of risk governance in terms of integration, suggesting that risk governance shapes interconnected activities within and between organisations, the reproduction of practices, and sense making and sense giving (see also Meidell & Kaarbøe, 2017).

Risk culture is also an important element in enabling ERM as a dynamic capability, as risk culture has been found to influence managerial preferences for various ERM practices (Diab & Metwally, 2021). Mikes (2011) draws attention to two quite distinct risk cultures: risk measurement and risk envisionment. In a culture characterised by risk measurement, risk experts focus on developing and using sophisticated risk calculation and aggregation techniques that are applied to prevent or control known risks; they tend to work within their own silos, and they have little influence on strategic decision-making. In a culture characterised by risk envisionment, risk experts develop, use, and share a wider array of anticipatory techniques (e.g., scenario planning, materiality analysis) in interactions with others, e.g., business managers, in dynamic and reflexive social spaces, e.g., committees and workshops, where individual difficulties in terms of understanding risk and uncertainty can be overcome (Tekathen & Dechow, 2013), where risk awareness can be increased (Braumann, 2018), and influence on decision-making can take place (Hall et al., 2015).

The contrast between the two approaches—measurement and envisionment—also highlights the challenges that senior risk officers face in balancing the tensions between compliance and business partnering, where in the latter approach, risk managers are expected to proactively assess and communicate uncertainty as opposed to acting as reactive control agents (Mikes & Zhivitskaya, 2017). These approaches necessitate distinct sets of competencies. Mikes et al. (2013) find that individuals who exhibit and are able to combine trailblazing (“finding new opportunities to use expertise”), toolmaking (“developing and deploying tools that embody and spread expertise”), teamwork (“using personal interaction to take in others’ expertise and convince people of the relevance of your own”), and translation (“personally helping decision makers understand complex context”) competencies are best equipped to gain organisational-wide influence. As Braumann et al. (2024) point out, the role that risk experts take is closely related to the integration of ERM with other controls that make up the organisational control package and the extent to which ERM influences other controls such as strategic planning.

The design and use of risk artefacts, i.e., tools, is another significant aspect in enabling ERM as a dynamic capability. The ERM process is a tool-rich environment, and the literature shows that, depending on how risk artefacts are designed and used, their contribution to ERM in terms of dynamic capabilities varies considerably. As an illustration, the implementation of ERM artefacts may lead to knowledge conflicts between groups and reduced discretionary decision-making (Wahlström, 2009) or support the emergence of risk communication (Klein & Reilley, 2021), operationalise risk aggregation techniques (Arena et al., 2017), and facilitate the inclusion of risk information into strategic decision-making forums (Giovannoni et al., 2016). Additionally, ERM artefacts may facilitate knowledge circulation (Tekathen & Dechow, 2013) and either reduce or increase decision uncertainty (Mikes, 2011). Thus, it is important to consider the manner in which ERM, functioning as a dynamic capability and source of strategic value creation, utilises various technological solutions or what Crawford and Jabbour (2024) refer to as ERM artefacts, to support ongoing activities, promote risk awareness, increase responsiveness to threats and opportunities, and enhance information sharing across the organisation (Arnold et al., 2011).

Finally, given that the cognitive capabilities of managers within organisations have been credited in the literature with effective dynamic capabilities (Andersen et al., 2022; citing Helfat & Peteraf, 2015), it is therefore critical to acknowledge the significance of human cognition. Upon revisiting the definition of dynamic capabilities presented at the beginning of this section—“a firm’s ability to integrate, build, and reconfigure internal and external competencies to address rapidly changing environments”—and drawing insights from relevant literature, it is evident that in order for organisations to embrace new ERM ideas that would result in ERM becoming a dynamic capability, human cognition may need to be adapted to realise the integration, building, and reconfiguration of competencies (Nair et al., 2014). While the complexity of cognitive processes is often overlooked in the risk management literature (Rooney & Cuganesan, 2015), a few studies offer valuable insights into the diverse mechanisms through which cognitive adaptation can occur.

Cognitive resources should be reallocated from box-ticking to the actual management of risks, according to Power (2009). Consistency in perceptions is important for the success of the risk control process according to Woods (2009), and Caldarelli et al. (2016) contend that communication is necessary for the emergence of shared perceptions, otherwise there is a risk that individual autonomous conflicting opinions persist. Achieving consistency in perceptions may be difficult however given the multiplicity of perceptions that exist in relation to risk and how it should be managed (Klein & Reilley, 2021). According to Mikes (2009), interactive controls should be used to increase actor’s awareness of emergent risks in order to share discretionary decision-making and emergent strategies. Corvellec (2010, p. 146) asserts that risk conceptualisation, according to the cognitive view, is “contingent on, comes from, and develops within practice”. Arnold et al. (2011) and Braumann (2018) highlight the significance of technological solutions, i.e., risk artefacts, in facilitating risk awareness. However, Christiansen and Thrane (2014) caution that although individuals may be more risk aware, this does not automatically lead to action. As stated by the authors, to generate action further translation is needed, i.e., assessing operational consequences or suggesting possible responses (Christiansen & Thrane, 2014, p. 436). The literature shows that CROs who engage in business partnering are more likely to engage with business managers in the translation activities, thus sharing the cognitive burden that ERM presents for actors, in terms of sense making and sense giving (Meidell & Kaarbøe, 2017).

2.2 Resilience

The term resilience is becoming increasingly prevalent in research, public policy, and the media, and it is widely regarded as a desirable trait for organisations to possess in order to deal with a variety of adversities (Linnenluecke, 2017). A comprehensive literature review of business and management research reveals how fragmented the concept’s conceptualisation and operationalisation has become, as it is associated with significantly different approaches to dealing with adversity, that range from rigidity on one end of the spectrum to agility on the other (Linnenluecke, 2017). Nevertheless, the increasing prevalence of the resilience concept across a variety of scientific disciplines and practitioner communities suggests that it is an essential concept, as it is strongly related to environmental and societal change phenomena such as unexpected and disruptive events (Hillmann & Guenther, 2021). Additionally, since resilience has been linked to environments characterised by uncertainty, complexity, and turbulence (Hillmann & Guenther, 2021), it is a relevant concept from a risk management perspective.

Resilience can trace its roots back to the 1970s in ecology. Early scientific definitions refer to resilience as “a measure of the persistence of systems and their ability to absorb change and disturbance and still maintain the same relationship between populations or state variables” (Holling, 1973, p. 14). According to this definition, resilience refers to its original connotation of persistence. With the passage of time, the concept of resilience has developed further within different disciplines (Linnenluecke, 2017). In social ecology study, for instance, the resilience concept expanded and embraced the capacity of a system to adapt and transform in the face of change (Walker et al., 2006). In the same vein, management scholars define resilience as “…the ability of systems to absorb and recover from shocks, while transforming their structures and means for functioning in the face of long-term stresses, change, and uncertainty” (Van der Vegt et al., 2015, p. 972). Finally, from an organisational resilience perspective, “resilience is more than mere survival; it involves identifying potential risks and taking proactive steps to ensure that an organisation thrives in the face of adversity” (Baird et al., 2023, p. 171, citing Somers, 2009, p. 13)Footnote 3. Thus, it can be argued that resilience is not only limited to a system’s ability to bounce back from disturbances and stay in the same state. It can also refer to a system’s capability to undergo transformational change and bounce forward, to a new state. According to Andersson et al. (2019, p. 37), this implies that in achieving resilience, organisations maintain a balance between ‘opposing forces’, i.e., between short-term efficiency and long-term development.

Although resilience is typically conceptualised in terms of post-disturbance outcome states related to performance (Munoz et al., 2022), this study views resilience as an ongoing and dynamic process through which organisations continually adapt in order to meet the current challenges that complex environments present, thereby increasing their capacity to meet future challenges also. This developmental perspective recognises that resilience does not emerge solely from managing one-time exceptional events, instead, it emerges from the ongoing management of risks and the ability to activate, combine, and recombine resources in response to new challenges that arise over time (Sutcliffe & Vogus, 2003). Therefore, we follow the argument that resilience—in terms of resources and capabilities—“can be formed over time, strengthened and developed through a series of experiences, mutual learning and the gradual build-up of competence to handle challenge, stress and strain” (Richtnér & Södergren, 2008, p. 262, citing Sutcliffe & Vogus, 2003).

As Van der Vegt et al. (2015, p. 973) point out, “to understand a system’s [organisation’s] resilience, it is important to identify the capabilities and capacities [resources] of important parts of the system, and to examine how they interact with one another and their environment”. Thus, in line with taking a developmental perspective, this study focuses on resilience as capacity-derived resources (Richtnér & Södergren, 2008) and action-derived capabilities (Jaeger, 2010). As a starting point, we draw on Richtnér and Södergren’s (2008) definitions of resilience resources which are based on the work of Sutcliffe and Vogus (2003). We subsequently enrich these definitions, where possible, by drawing on work which examines resilience in relation to creativity (Richtnér & Löfsten, 2014), transformation (Lengnick-Hall & Beck, 2005; Lengnick-Hall et al., 2011), and balancing organisational structures (Andersson et al., 2019).

Structural resources are defined as “clear organisational structures which facilitate activity, solid visions and plans, adequate financial resources, a legitimate position, a clear mandate, enough formal power, or a platform to act from” (Richtnér & Södergren, 2008, p. 269). By providing a formal setting, structural resources play an important role in the integration and development of relational and cognitive resources at the individual, group, and organisational levels (Lengnick-Hall & Beck, 2005). At the individual level, structures can facilitate the exercise of discretion and judgment. At the group level, they can facilitate learning, skill development, and reinforce a learning orientation. At the organisational level, structures that promote flexibility can support the transfer of expertise and other resources via ad-hoc problem-solving networks and through the development of social capital (Sutcliffe & Vogus, 2003).

Relational resources are defined as “networks that can be mobilised, people who in practice will welcome being contacted, and who can, for instance, open the right doors, or contribute with material or immaterial support. This type of resources can include colleagues in other organisations, good relations with external partners, and significant others such as subcontractors, consultants, customers, and politicians” (Richtnér & Södergren, 2008, p. 269). If these networks interact in mutually reinforcing ways, they facilitate the acquisition of new skills, the mastery of new situations, and competence enhancement (Gittell, 2000; Gittell et al., 2006). They also enable the accumulation of existing knowledge which in turn enables the development of new knowledge. The expansion of a group’s collective knowledge in conjunction with a diverse group composition, can according to Sutcliffe and Vogus (2003, p. 102), foster resilience “by influencing the group’s capabilities to sense, register, and regulate complexity”.

Cognitive resources are defined as having “adequate skills, knowledge, and competence, either in the team, or easy access to the skills of others, for instance expert knowledge, mentors with earlier experience or smart people to discuss crucial issues with” (Richtnér & Södergren, 2008, p. 269). As indicated above, cognitive resources, such as risk expertise, are crucial to the development of organisational resilience, and supportive structural and relational resources play a significant role in the emergence and development of cognitive resources over time. Lengnick-Hall and Beck (2005, p. 750) emphasise the importance of cognition in their conceptualisation of ‘cognitive resilience’, and its role in noticing, interpreting, analysing, and formulating responses to complex challenges and unprecedented events that go beyond simply surviving an ordeal, i.e., bouncing back. This suggests that the cognitive resources needed to enable organisations to transform, i.e., bounce forward, are different because in bouncing forward there is an emphasis on ingenuity rather than standardisation and the need for control (Lengnick-Hall & Beck, 2005). Thus, cognitive resilience is regarded as “an intricate blend of expertise, opportunism, creativity and decisiveness despite uncertainty” (Lengnick-Hall et al., 2011, p. 246).

While we take the position that resilience is a developmental process, drawing on Jaeger’s (2010) work enables us to link the developmental and processual aspects of resilience, with resilience capabilities, which is important when examining the relationship between resilience and strategy, and it also avoids conceptual fragmentation (Andersson et al., 2019). The three forms or orders of resilience are defined as follows.

First-order resilience “is based on patterns of conventions and norms that keep solving coordination problem in the face of perturbations” (Jaeger, 2010, p. 14). In other words, first-order resilience is rooted in the probability-utility framework and refers to a system’s ability to avoid undesirable but known events and can therefore maintain coordination in the face of disturbances (Jaeger, 2010). This form of resilience is primarily associated with robust patterns, norms and conventions, where systems [organisations] have learned to manage preventable and controllable risks in stable conditions, and is effective under predictable circumstances (Jaeger, 2010). Second-order resilienceFootnote 4 is “the capability to handle the breakdown until the system can switch back into its normal way of operation” (Jaeger, 2010, p. 15). This refers to a system’s [organisation’s] capacity to bounce back after a breakdown (i.e., where risks and uncertainties exceed the coping capacity of first-order resilience) to the “previous state of normality” and thus depends on the firm’s capability to improvise (Jaeger, 2010, p. 15). Third-order resilience is related to “the capability of a system [organisation] to find a creative answer to the disruption it has experienced” (Jaeger, 2010, p. 15). In doing so, the system finds ways to learn from the disruption and reduce the vulnerabilities it encountered. Achieving third-order resilience is contingent on organisations treating disruptive events as opportunities rather than threats (Vogus & Sutcliffe, 2007) and requires the mobilisation of relational and cognitive resources in particular, where networks within and outside the organisation are mobilised, and actors’ skills, knowledge, and competencies are leveraged to create innovative solutions (Richtnér & Löfsten, 2014). This form of resilience is closely related to what Mikes and Kaplan (2015, p. 40) refer to as risk “envisionment”, which relies heavily on “experience, intuition, and imagination”.

A summary of our theoretical coordinates is provided in Table 1, followed by a discussion on their applicability in analysing our empirical case in Sect. 2.3.

2.3 Applying the theoretical coordinates to ERM

Following resilience thinking, several researchers have attempted to establish a link between resilience and risk management (e.g., Aven, 2019; Van der Vegt et al., 2015), thus promoting the widespread notion of risk-resilient organisations (Aven, 2019; Bogodistov & Wohlgemuth, 2017). This notion, which is also the focus of the dynamic capability perspective, suggests that organisations should be able to rapidly reconfigure their resources in response to changes in environmental uncertainty (Winter, 2003). The latter argument is consistent with what we discussed earlier (i.e., in Sect. 2.1.1) on how resources and capabilities emerge in the context of ERM practices in terms of developing risk governance frameworks (i.e., structural resources), risk culture, the design and use risk artefacts (i.e., relational resources), and risk cognitive capabilities (i.e., cognitive resources). In a similar vein, Van der Vegt et al. (2015) argue that in conditions of uncertainty, organisational structures should be more organic, new forms of corporation developed, decision-making should be decentralised, and greater interconnectedness amongst employees fostered, all with the aim of creating adaptive problem-solving capabilities (i.e., first-, second-, and third-resilience capabilities). Moreover, Van der Vegt et al. (2015) emphasise the importance of individual’s behaviour, abilities, skills, and cognitions. In doing so, they underscore once again the significance of relational and cognitive resources in addressing uncertainties commonly associated with high-risk strategic transformations. Thus, risk-resilient organisations can thriveFootnote 5 and flourish despite volatility and uncertainties (Munoz et al., 2022; Taleb, 2012). It is against this background that we believe unpacking resilience ‘capacity-derived resources’ and ‘action-derived capabilities’ (Table 1) is useful in further bridging the gap between ERM and resilience for the following reasons:

First, the identified capacity-derived resources (i.e., structural, relational, and cognitive resources) emphasise the importance of establishing formal structures and control activities, encouraging collaborative effort, and enhancing cognitive processes, so that risks and uncertainties can be better governed and managed. These factors have been receiving increasing attention in the risk management literature. While the literature focusing on risk governance emphasises the importance of structural resources as a means of controlling (undesired-) behaviour (Lundqvist, 2015), other literature within the domain of risk management increasingly emphasises relational and cognitive resources in terms of enhancing behaviour to create more reflexive and intelligent risk management practices in daily organisational life (Crawford & Jabbour, 2024; Tekathen & Dechow, 2020). These resources manifest, for instance, when actors use social capital (i.e., networks of relationships) to influence decision-making (Hall et al., 2015), or when value systems are modified intentionally to instil new risk ideas in the minds of employees (Metwally & Diab, 2021).

Second, the three distinct orders of resilience action-derived capabilities emerged as an attempt to advance the development of risk management theory and practice (Jaeger, 2010), which makes them highly relevant for advancing our theoretical and practical understanding of how ERM contributes to resilience in the context of a high-risk strategic transformation. An underlying facet of action-derived capabilities is that they indirectly acknowledge the role and importance of risk governance, risk culture, risk artefacts, and cognition in achieving first-, second-, and third-order resilience. To illustrate our point, risk governance is central to ensuring that an organisation has a formalised and structured approach in place to manage preventable/controllable risks (Lundqvist, 2015) (first-order resilience), as well as having the capability to bounce back after a breakdown by having disaster recovery plans and business continuity plans in place (second-order resilience) (Bhamra et al., 2011). In addition, given that risk governance also influences interconnected activities and the extent to which organisational actors engage with each other in sense making and sense giving (Boholm et al., 2012) it is reasonable to assume that risk governance has a role in supporting the emergence of creativity and learning (third-order resilience).

Similar connections between resilience and ERM can be made for risk culture, risk artefacts, and cognition. For example, given that risk culture influences managerial preferences for various ERM practices (Diab & Metwally, 2021), risk culture can limit action-derived capabilities to first-order resilience or extend them to include all three orders of resilience. Risk artefacts may be predominately designed and used in the assessment and mitigation of preventable/controllable risks, but they can also be designed and used to augment improvisation in social spaces shared by risk experts and business managers, or to enhance organisational learning by improving risk communication across distributed organisational actors (Klein & Reilley, 2021). Human cognition can be limited to focusing on risk prevention and control from a compliance perspective (Power, 2009), or extended to include creative problem solving to enter a new state by engaging in strategic decision-making (Corvellec, 2010).

Third, the literature suggests (e.g., Van der Vegt et al., 2015), and we argue, that it is not only likely that the three types of resources, and the three orders of resilience have a dynamic relationship within their own domain (e.g., structural resources are related to relational resources, or first-order resilience is related to second order resilience). It also appears plausible that capacity-derived resources and action-derived capabilities may have a dynamic relationship across domains, especially as risk governance matures sufficiently to achieve ‘integrated’ enterprise risk management, which connects internal systems, processes, techniques, and people (Lundqvist, 2015, p. 442). Given that organisations who engage in strategic transformations must strike a balance between current governance issues and future-orientated transformation strategies (Carmeli & Markman, 2011), it is likely that organisations via their ERM processes need to mobilise several of the resources simultaneously, in order to achieve action-derived capabilities (Table 1) and thus develop resilience as they enter, change, and emerge from the strategic transformation.

3 Research method

The research purpose outlined in the introduction is addressed by using a qualitative methodology and a single case study approach. Due to the relationship-based nature of our research question, a case study was selected to facilitate the detailed investigation that is typically required to answer why and how questions (Gerring, 2004; Rowley, 2002), and to understand complex dynamics in a specific context (Yin, 2009).

3.1 Case selection

In line with our research purpose (Rowley, 2002; Siggelkow, 2007), we selected NordMine. It is one of Sweden’s oldest industrial companies, which is state owned, and produces approximately 85 percent of all the iron ore in Europe. As Europe’s largest iron ore producer and fourth largest source of CO2 emissions in Sweden, it reformulated its strategies toward full decarbonisation in 2020 which coincided with the EU’s adoption of legislative proposals to achieve climate neutrality by 2050 and an intermediate target of a minimum 55% net reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by 2030 (European Commission, 2023). As a result, NordMine’s risk and uncertainty landscape is changing dramatically, as are its risk management practices to ensure the achievement of its strategic ambitions. Due to the nature of NordMine’s core business, financial risks and business interruption risks have historically been the company’s primary risk management priorities however, due to the strategic transformation towards sustainability, the company has been faced with new strategic risks and uncertainties that require it to change its capacity-derived resources and action-derived capabilities and maintain alignment between risk management and strategy (Sax & Andersen, 2019). Therefore, the case company provides a valuable empirical context to increase our knowledge of how risk management practices can evolve over time and thus enable resilience in an organisation.

3.2 Data collection

We gathered empirical data from a variety of sources: (1) semi-structured interviews, (2) non-participant observation, and (3) secondary data from the company’s official documentsFootnote 6. From June 2022 to September 2023, the corresponding author conducted 25 semi-structured interviews (see Appendix 1). Interviewees were selected using snowball sampling based on recommendations from previously interviewed participants. Before the interviews began, we outlined a set of issues that needed to be explored with each respondent.Footnote 7 All interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Additionally, as a non-participant observer, the corresponding author was present at one of the company’s risk meetings alongside local risk managers and a group of international risk standard-setters. This observation allowed for a more in-depth contextual understanding of the company’s integrated risk management approach, the key objects in risk identification and assessment processes, the essential tools for assessing different risks, and the policies and requirements for risk management.

Lastly, secondary data was gathered from public and confidential company documents. This data comprised of the company’s sustainability and annual reports from 2012 to 2022, the internal risk policy, the company’s risk management handbook for business interruptions, strategic planning documents, annual risk grading reports, strategic meetings’ PowerPoint slides, and archival data included in the company’s websites and business publications.

To understand how enterprise-wide risk management has evolved and influenced the development and maintenance of structural, relational, and cognitive resources of the company as well as its strategic transformation process, we collected and thereafter analysed data from different organisational levels including executiveFootnote 8, group managementFootnote 9, business areasFootnote 10, and operational levelsFootnote 11. This enabled us to understand ERM practices from multiple perspectives and get closer to the resources that facilitated the emergence of resilience capabilities (Dooley, 2002; Klein et al., 1994). Thus, we could better understand the interactions and dynamics between and across the resilience capacity-derived resources and action-derived capabilities (Table 1).

3.3 Data analysis

Since we utilised an abductive approach, data collection and data analysis were iterative processes and we went back and forth between data, emerging results, and the theoretical framework (Christensen et al., 2002; Gehman et al., 2018; Van de Ven, 2007; Van Maanen et al., 2007). For data analysis, we followed the temporal bracketing approach (Langley, 1999) and employed thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006; Gioia et al., 2013). The combination of these methods was essential for answering the research question due to the following considerations.

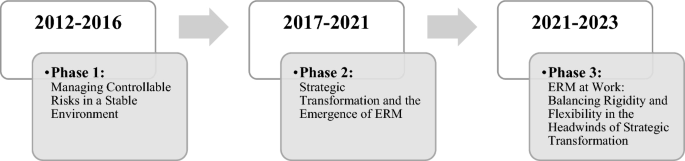

Firstly, the temporal bracketing approach helped us to structure our data in a way that illustrated the historical evolution of ERM practices from 2012 to 2023, based on critical events and interactions (see Fig. 1) in the context of transformative change happening at NordMine. According to this, we began to dissect and reorganise the original interview transcripts, field notes, and secondary data around the events that were significant to our understanding of the change processes in the company. Thus, temporal bracketing facilitated the transformation of our empirical findings into a series of independent but connected blocks (Langley, 1999), namely Phase 1 (2012–2016): managing controllable risks in a stable environment, Phase 2 (2017–2021): strategic transformation and the emergence of ERM, and Phase 3 (2021–2023): ERM at work: balancing rigidity and flexibility in the headwinds of strategic transformation. We identified each phase based on the key events that occurred in those time periods as they related to the company’s risk management and changes in strategy. This, in turn, enabled us to analyse the events of each phase within the different theoretical coordinates. Although each of the phases separately describe the risk management processes and practices during a specific period, there is continuity between different phases (Langley, 1999). For instance, as illustrated in Table 2, resilience capacity-derived resources and action-derived capabilities have been developed during different phases, strengthened through a series of events, and thus gradually built up NordMine’s ability to manage risk and uncertainties (Richtnér & Södergren, 2008).

Secondly, using thematic analysis enabled us to find the pattern of interpretation within three phases of our empirical findings with reference to the theoretical coordinates presented in Table 1. According to this, our data extracts were grouped and coded according to first-order analysis (Gioia et al., 2013) themes, namely resilience structural, relational, and cognitive resources as well as resilience capabilities including first-, second-, and third-order resilience. As the data analysis progressed, during the second-order analysis (Gioia et al., 2013), we found interrelationships between and across the themes related to capacity-derived resources and action-derived capabilities. Thereafter, our empirical storyline was developed based on those themes and connected to our theoretical framework.

4 Empirical results

This section presents the empirical results from our study. In Sect. 4.1, we begin with a brief overview of the case study setting, three phases of risk management in NordMine, and then elaborate upon ERM development in Sects. 4.2.1 through to 4.2.3.

4.1 NordMine

NordMine as one of the world’s leading suppliers of upgraded iron ore products, carries out its operations in two main business areas, namely Iron Ore and Special Products. While the former encompasses the company’s mines and the related processing plants, the latter develops and markets industrial minerals, drilling technology, and full-service solutions for the mining and construction industries. In 2020, external factors, such as regulation and changing stakeholder demands for sustainability, and a vision for the future of mining, became important drivers for NordMine to incorporate sustainability into its strategies. From a market perspective, the sustainability transformation would provide the company with a long-term competitive advantage and value creating opportunities, particularly in business areas that deal with a large number of customers. Furthermore, reformulating strategy according to sustainability objectives would enable NordMine to move toward resource efficiency and also broaden its business. However, this also presented the company with various types of risks. Thus, as a consequence of undergoing a transformative change, NordMine moved from traditional risk management towards risk governance as a stepping stone for developing ERM practices (see Fig. 1). In Phase 1—2012 to 2016—the company’s primary risk management priorities have been financial and business interruption risks with the aim of securing access to iron ore resources, stabilising availability in high-volume production, and ensuring profitability despite market fluctuations.

Later, in Phase 2, i.e., 2017–2021, group risk attempted to improve the risk management system and thus improve and expand how it identified and acted on risks and opportunities influencing the company’s competitiveness and its value creating capabilities. In doing so, group risk tried to design and implement ERM mainly by trial and error. Eventually, alongside the formulation of the new strategy, a new risk management policy was approved by the board and this important step helped group risk to bridge the gap between the company’s risk management and strategic planning process in phase 3. Finally, from late 2021 to 2023, the company was about to move into a key phase (i.e., Phase 3), as they entered into the thrust of the strategic transformation process, in which tensions between short-term efficiency characterised by stability, and long-term survival characterised by innovation, emerged. As a consequence, during this period, ERM has been tested in terms of contributing to NordMine resilience resources and capabilities as the strategic transformation began in earnest.

4.2 From risk management to ERM

This section provides empirical evidence of how risk management practices at NordMine developed from traditional risk management to enterprise risk management over the 12-year period, providing insights into how ERM contributed to developing and maintaining the resilience necessary for NordMine’s strategic transformation towards sustainability.

4.2.1 Phase 1—Managing controllable risks in a stable environment

The finance department managed the majority of the company’s financial risks by adhering to policy documents, e.g., the finance policy to guide the identification, analysis, and mitigation of price, currency, interest rate, credit, and financing risks so that robust financial performance and profitability could be maintained. As price volatility in the global iron ore market impacted the company’s earnings and cash flows, cash flow analysis was performed on an ongoing basis as well as a sensitivity analysis to consider external changes and thus manage risks accordingly. Additionally, in periods when the company was expected to have high outflows, longer hedging of the iron ore price was considered.

For managing currency risk (i.e., the USD/SEK exchange rate), which was also known as transaction and translation exposure, the company followed the group’s finance policy and hedged the risk in accounts receivable. To handle the interest rate risk which referred to how the return on an interest-bearing asset would be affected by a change in interest rates, the company decided to allocate its total assets to three portfolios and thus the finance policy governed the maximum average duration in each asset portfolio. Moreover, some frameworks were set in relation to each portfolio’s purpose as well as in relation to a range of risk measures and restrictions. Regarding financing risk, which might result in the company’s inability to meet its obligations due to a lack of liquidity or the inability to raise external loans for operating activities, the finance group defined investment and financing needs in accordance with the company’s strategy and developed a long-term plan for financing the investments by evaluating the costs and benefits. Therefore, prudent management of these financial risks, based on the risk policy, was essential to ensuring that the company had adequate financial resources to fund its activities as well as improving the company’s stability to continue its business as usual, and in case a disturbance occurred, the company could control and minimise the losses. In a similar vein, handling business interruption risks which were also related to preventing and minimising financial losses (e.g., reduced sales due to lack of production, increased costs of insurance and repairs to facilities) when a disruption happened, was the core focus of NordMine’s risk management between 2012 and 2016.

In 2012, the company’s insurance captive within group finance created the risk management handbookFootnote 12 to legally demonstrate that its operations had been designed to proactively avoid incidences and, as a result, qualify to purchase business interruption insurance. The handbook facilitated the implementation and adherence to certain standards (e.g., Swedish rules for fire protection and technical safety equipment for work machines/vehicles in the mining industry), and more importantly, it was a means of communicating with insurers that NordMine could effectively manage its business interruption risks, and in doing so, kept premiums down.

The insurance captive role was formally positioned within the finance department and reported to the chief financial officer (CFO). They ensured that NordMine had the most efficient insurance coverage in place, and conducted a yearly risk workshop in order to visit different business areas and unit (e.g., mine, above-ground processing, logistics, and harbour) managers in order to identify and assess what incidents would stop their production process. Accordingly, the insurance captive together with business managers developed risk metrics to measure the probabilities and impacts. This process was done in a very consistent manner, and the value for the risk assessment was mainly based on the “production volume”. The insurance captive together with the CFO consolidated the risk reports for the company’s main business areas, and thereafter the management of each business area received the risk metrics for the entire area which enabled them to understand what the main business interruption risks in their areas were, what would happen if the interruption risks were to materialise, and finally, they could see which combination of high probability and high risk was assigned to the risk metrics. These activities were complemented by site visits where the insurance captive—under the supervision of CFO—and together with internal and external operational risk specialists and engineers as well as some contacts from the insurance company, visited their different plants and production sites. Thus, the mobilisation of the network of actors, together with the site visits, in turn, helped the insurance captive to understand first-hand the risks in those plants or production sites which were later represented in the risk metrics. However, it should be noted that, in this risk management process, the insurance captive and the CFO—as they were within the finance group—were primarily responsible for identifying, assessing, and mitigating risks.

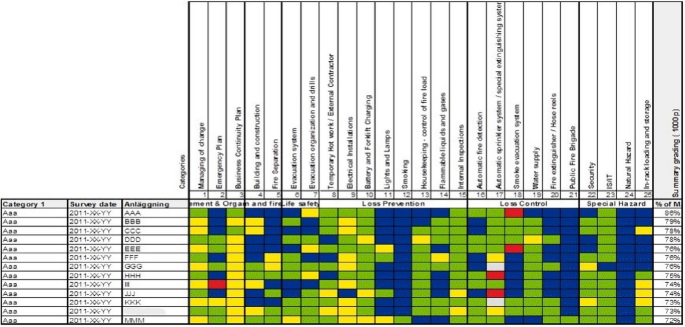

Since there was a strong link between business interruption risks and the company’s insurance policy, as a part of this process, the insurance captive of the company used the “risk grading” model (see Fig. 2), where different colours represented and visualised the level of risk in a particular areaFootnote 13, and if there were deviations from the legal and insurance requirements, recommendations for further work were given to the plant managers.

NordMine’s risk grading model (In the risk grading model, blue indicates that the operation area fully complies with the requirements for planned or new facilities in the company risk handbook; green illustrates the operation area fully complies with the requirements for existing facilities in the company risk handbook; yellow and red indicate a deviation from the requirements for which a recommendation for immediate actions is given; and finally, grey indicates that the risk is not applicable.)

NordMine conducted this risk process annually for many years, and it was considered successful due to its familiarity with all organisational actors, it was integral to managers’ understanding of the risks that the company was exposed to leading to the reduction or elimination of business interruption risks as awareness in relation to this risk type increased. Thus, those involved in the process contributed to it not because they were required to, but because they found it useful for the stability and continuity of their work. Furthermore, since this risk management template made it easier for managers to capture, visualise, and in some cases quantify the risks related to business interruption, this process attracted the attention of many managers and in turn, facilitated the process of risk communication, i.e., risk talk, for all organisational actors. Moreover, this risk management template contributed to stable levels of customer satisfaction given that by managing business interruption risks, NordMine could deliver high quality products to the customers without delays. The risk management handbook facilitated the mobilisation of different organisational actors, enabling NordMine to manage preventable/controllable risks and continue its business as usual, and in the event that an incident did occur, the company was able to minimise its losses and return to normal operations. The CRO explains:

The purpose of the risk management handbook is that we have the appropriate equipment and protection in place, so that, the incident never occurs [in the first place], and if there was an incident anyway, the consequence of that incident should be minimal, as little as possible. And that is where the active protection comes in, where we have firewalls or active fire extinguishing systems, alarms, cameras, etc. So, if an incident happens, it only impacts a small part of operations, it does not impact [the whole] production. So, it is both ensuring incidents do not happen and minimising the effect if they do.

Despite the fact that this risk management template was successful for many years and had the support of the managers, in 2013, the company’s finance group, especially the insurance captive together with the CFO, began to realise that while having an insurance captive was necessary, it was no longer sufficient given the company as part of its strategy, aimed to expand its mining and processing operations rapidly, at the same time as it was operating in an increasingly turbulent environment with increasing risk reporting requirements. While the insurance captive would safeguard operations from incidents and minimise losses, it did not add value to the company despite having many advantages such as tax benefits, low premiums, complying with regulatory requirements, building trust and efficient communication with insurers, and expanding the network within the insurance market. Towards the end of 2013, the finance group decided to change the risk management template in order to re-align risk management with the changing strategy and thus create value.

As a consequence, in 2014, NordMine established the CRO role which was an important and early step in developing the company’s structural resources that, in turn, facilitated solid visions, legitimate position and clear mandate. In doing so, the insurance captive role was extended to include the management of strategic risks that might affect the company’s ability to achieve its overall financial and sustainability objectives. As the person who had the insurance captive role already had extensive skills, knowledge, and competence in governing and managing insurable risks, she/he became the natural candidate for the new CRO position. As this was essentially a hybrid position at first, the new CRO spent 70–75 percent of her/his time on insurance-related work (i.e., administrative tasks related to insurance coverage and ensuring that documents such as risk management handbook were up to date, conducting business interruption risk workshops, and performing site visits), and the rest on strategic risk management, namely identifying and reporting critical risks.

As a result, having an insurance captive was a good foundation for advancing NordMine’s risk management since, in 2015, the CRO began to map and analyse risks, and submit proposals to the finance group and the board regarding how strategically important risks could be avoided, reduced, or even accepted by various company divisions and group management. This process evolved further in 2016, as a new CRO who was also responsible for insurance process of the company, took over from the previous CRO. In 2016, as NordMine’s business and mining operations expanded, the company made changes to its organisational structure meaning that most of the decision-making processes became decentralised. As a consequence, the responsibilities for identifying risks changed and more organisational actors became involved in the company’s risk work. In this regard, the CRO was tasked with coordinating the company’s risk management process and informing group management of the company’s risk exposures during the quarterly strategic meetings. As part of that coordination process, interactions between group risk (i.e., the CRO and the CFO) and managers in the business areas began to increase and in addition to financial and business interruption risks, strategic risks were also included in the risk management process.

In sum, during phase 1, NordMine had developed its structural resources (e.g., finance policy, risk management handbook), relational resources, such as collaboration between insurance captive and business area mangers, as well as other internal and external operational risk specialists and engineers, to identify and respond to business interruption and financial risks. Furthermore, NordMine’s cognitive resources began to expand during this phase as the insurance captive and the CFO who had expert knowledge in risk, consolidated the risk reports, thereafter shared the risk results with different business areas managers and mentored them to better understand the business interruption risks, and more importantly, anticipate what would happen if business interruption risks were to materialise. As a result of developing these resources, NordMine could improve its first- and second-order capabilities during phase 1, because risk management enabled the company to have robust financial performance by stabilising the production process and ensuring profitability, as well as minimising losses and returning to normal operations (i.e., continuity of the business) if an interruption occurred. However, as the findings shows, in addition to stability and continuity, value creation through risk management became a crucial issue for NordMine during phase 1, and as a result group risk aimed to advance the risk management process by considering strategic risks and developing the structural, relational, and cognitive resources further.

4.2.2 Phase 2—Strategic transformation and the emergence of ERM

Between 2017 and 2019, group risk worked to revise the existing risk management process, an exercise which was done mainly through trial and error, for instance, by trying to use the ISO 31000 framework or other common trends in risk management and reporting to establish which practices would best fit NordMine’s needs. The intention, from group risk’s perspective, was to create a high level of risk awareness throughout the company by involving all the business areas in the risk management process. If this intention were to be accomplished, NordMine would be able to identify and act upon risks and opportunities more quickly, thus affecting the company’s competitiveness and value creation capabilities. But everything did not go smoothly at first. When the CRO received the quarterly risk reports from the business managers, they were unstructured and contained a great deal of information, not all of which was relevant. The reason for this lack of quality according to the CRO was that risk management tasks were not prioritised by the risk managers as part of their role at that stage.

In November 2020, NordMine made the most significant strategic change in its 130-year history. According to the new strategy, the company aimed to achieve zero carbon emissions from its processes and products by 2045 by shifting to innovative and competitive mining as well as iron ore and mineral processing to produce climate-efficient quality products. Once the strategic goals were set, this necessitated a significant change to existing procedures, values, and mindset on risk and uncertainty governance and management in order to transform from an old industrial company, to becoming a world leader in innovation in this area. As a consequence, NordMine faced many new challenges. The CRO explains:

In setting the new strategic goals, the board increased the challenges faced by the business, which also means introducing a higher level of risk than before. By setting these strategies our company decided to say that is prepared to take much higher risks.

The level of risk and uncertainty had increased significantly as a result of the new strategy and the aggressive timeline, i.e., how to continue mining in a safe and economic way in the short-term while surviving and thriving in a climate-challenged environment in the long-term. Not only had new sustainability-related risks emerged, but new facets of existing risks such as finance and investment risks also emerged. This prompted group risk to rethink their approach, and NordMine decided to implement a new holistic ERM template, resulting in extensive changes to existing processes, techniques and roles, in order to support strategic decision-making and increase the likelihood of achieving the strategic transformation that was at the core of their new strategy and crucial for their long-term survival.

As a first step, group risk, including the CRO and CFO, initiated and engaged the wider organisation in reviewing all of NordMine’s steering documents, including policies and guidelines, to assess their validity. More specifically, in regard to the risk policyFootnote 14, group risk aimed to see if the company’s steering documents were dealing with the crucial risk areas that NordMine was faced with, and to assess if it was easy for managers at different levels to understand what the company expected from them concerning the risk management process. The CRO explains:

The policies and guidelines [of the company] are all important tools to ensure that we are steering the company in the right direction and that the company has internal control of major risks. By reviewing the old policies, group risk noticed a gap [between the new strategy and risk management] and this is how the new risk management policy of the company came about in February 2021.

Therefore, the risk management policy document, which was created and developed in 2020 by the CRO and CFO, was sent to the board of directors and received their approval in February 2021. Formal approval of the risk policy by the board helped to establish the “tone from the top”, and this further help facilitate the ERM implementation process.

The primary objective of creating the risk policy was to promote the notion that risk needed to be conceptualised as part of every decision, and risk management had to be a part of the strategic planning and follow-up process, and how, in general, NordMine controlled and steered the company. Therefore, to achieve this objective, the CRO cooperated with the CFO to develop the risk management policy. The CFO had a key role in this process since she/he could open the right door for the CRO by helping her/him to have access to top-level managers and importantly take part [as a listener] in the executives’ strategic planning meetings. As a result, by developing the new risk management policy and linking it to the strategic planning process, not only did group risk close the gap between risk management and the strategy formulation and implementation processes, but also attempted to improve the company’s resilience capabilities by defining a clear organisational structure and mandate which in turn would facilitate the mobilisation of different managers who could contribute to the risk management and strategic planning processes given their special expertise.

By 2021, ERM had officially become a part of the group’s strategic planning process and it was monitored by the group’s management system in the company. The integration of ERM and strategic planning would help managers ensure the balance of risk-taking in relation to the goals at the strategic, tactical, and operational levels according to the risk appetite. Moreover, the identification, prioritisation, description, and follow-up of strategic risks needed to be carried out annually by the business areas and staff functions as a part of their business planning process and be reported to the CRO. The CRO, in turn, was responsible for consolidating quarterly risk management reports to group management and the board as well as updating the company group’s strategic risk register. Accordingly, group risk would be able to identify the main risks so that they could connect them to the overall goals of the company, and as a result, would identify the main areas that they needed to focus on, and take action in order for NordMine to be able to achieve their objectives.

Consequently, the risk management policy became a convention for determining and supporting the ERM process, by informing business areas and staff functions what was expected of them, and more importantly, distributing risk ownership amongst managers at different organisational levels. This also encouraged the managers to have a risk mentality, i.e., adequate risk knowledge, and ensure that they have a dynamic process in place in order to always be prepared to deal with risks and survive in an ever-changing environment. In fact, due to the emergence of new sustainability-related risks, the CRO alone was unable to identify and assess all types of risks and integrate them with the strategy formulation process on her/his own. Therefore, she/he needed to involve different managers with diverse competencies in a truly holistic and integrated ERM process. The CRO elaborates:

I cannot be strong enough on my own, I can be the ambassador for the risk management process, [but]it needs to be the managers’ priority to work with risk, understand risk, and push that out through the organisation.

In sum, during phase 2, NordMine concentrated mainly on improving its resilience resources. For instance, in 2020, efforts to revise the company’s steering guidelines and adding the risk policy show how the structural resources of the company have strengthened in line with the strategic transformation. In a similar vein, the findings show that in 2021, by developing risk policy—as a convention for supporting ERM—group risk aimed to distribute the risk ownership among different managers, which in turn would contribute to developing relational resources by establishing relationships within the company to address strategic risks and environmental challenges. By developing the risk policy, group risk had also aimed to influence the company’s cognitive resources to expand them further. The intention of encouraging managers to have a “risk mentality” emphasised the importance of having adequate risk knowledge within organisational groups in order to make better strategic decisions. Finally, due to strategic changes happening in 2020, NordMine needed to equip itself with structural, relational, and cognitive resource development to not only continue and survive in a climate-challenged environment—that is related to first- and second-order resilience capabilities—, but to also facilitate the emergence of third-order capabilities to thrive in a turbulent environment and influence the company’s long-term success.

4.2.3 Phase 3—ERM at work: balancing rigidity and flexibility in the headwinds of strategic transformation

Although introducing the policy and having it approved by the board in 2021 was an important step in facilitating the implementation of ERM in NordMine, it was only an overall framework and therefore did not provide detailed guidance on how risk management should be carried out within the business areas. The CRO clarifies:

The risk management policy [can be regarded] as the umbrella at the top. The policy does not go as far as saying what business areas and support functions need to do. Each business area and support function need to figure out how they should implement it to ensure that they are getting a meaningful picture of their risks in the strategic planning process, how they identify the prioritised activities and how they follow them.

Even though the company designed and began implementing ERM in 2021, it is still in the learning phase regarding how to work with the various types of risk and how to increase its success rate in achieving strategic goals during a period of rapid change and transformation. In practice, this has been difficult and triggered some issues. On the one hand, group risk needed to monitor current operations for financial and business interruption risks and minimise those risks, because that is how they finance the transformation and expansion strategies. On the other hand, they needed to focus on strategic risks and find new ways to identify, assess, and prioritise those risks in order to create value for the company as well its stakeholders. The latter requires advanced risk management processes at different organisational levels, in order to comply with the risk management policy, and to lead to different resilience capabilities.

Delegating responsibility to the business areas to develop their own guidelines in line with the risk policy was considered a necessary step in integrating risk management into the strategic planning process. Even though three years has passed since the introduction of the risk policy supporting the shift to the ERM template, no such guidelines had been developed and implemented in the company’s various business units and the quality of business area reports was still not at the level they were supposed to be. As a result, embedding ERM in business areas’ [daily] operations is an issue that still needs to be solved. The CRO explains:

I think that’s the problem, I have been in contact with the business areas. I stretched out my hand to the business areas at their leadership level. I suggested we run workshops with them to see together how we can meet the risk policy requirements, and how they can work in their business areas in a way that [when] they come to the top level [meetings] they are more prepared [concerning]what their top risks are and how their activities would handle those risks. I felt that they were very interested and grateful for that, but there are always other things that are more urgent [concerning the transformation process] right now for the managers.

While extending the roles of business managers to include risk management tasks was considered by group risk to be an essential aspect of linking ERM and strategy, and extending risk management skills, knowledge, and competence to the wider organisation, the transformation is an attention-demanding process in which there are numerous emerging issues with higher priorities both for business managers and the executive management team. While much work had gone into changing the risk governance framework and risk management processes so that they would be aligned with the new strategy, ERM was struggling to gain influence on executive and operational decision-making. However, this issue did not hinder the development process of structural, relational, and cognitive resources in NordMine.