Abstract

Despite the growing interest in research on the topic of internal control, there is confusion about the concept in both theory and practice. This study addresses this lack of clarity by systematically structuring the literature that uses the concept by investigating what we know from previous studies about the practice of internal control and how it is institutionalized. To examine the existing literature in this field, the paper utilizes the theoretical lens of ‘institutional work’. The review finds that the understanding of internal control is currently divided: one part of the literature understands the concept as internal control over financial reporting, while the other part has a more global and strategic understanding of the term. Internal control is institutionalized by different organizational actors at the micro level in an attempt to implement internal control systems that are not a simple act of compliance but present an added value for the organization. At the same time, it is noteworthy that not all categories of institutional work could be identified in the internal control literature, indicating that the actors are largely limited by their institutional embeddedness. The paper also presents an aggregated understanding of the term internal control, which can therefore significantly supplement the efforts of practitioners and regulators to implement internal control procedures that add value for the corporate governance of organizations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Research on internal control is increasing and has focused on many different aspects of the subject, such as the design and implementation of internal controls (e.g. Dikan et al. 2014; Bogdan 2014), the determinants (e.g. Jokipii 2010), as well as the effect that internal controls (or the lack of) have on organizations (e.g. Lee et al. 2016; Brown and Lim 2012). However, continuing scandals and failures in many companies around the globe (e.g., Enron, WorldCom, Volkswagen) show that the issue of risk and how to mitigate it through internal control efforts is far from resolved. The purpose of this study is to provide a systematic literature review that investigates the different streams and meanings of internal control in the research. This review goes beyond other systematic reviews in the field by employing a theoretical framework that enables a content analysis of what internal control means in practice.

The practices of internal control and management control are closely connected. While management control aims at steering organizations through the organizational environment toward the achievement of both short-term and long-term goals (Otley and Soin 2014), internal control contributes to this process by providing reasonable assurance regarding the effectiveness and efficiency of operations, reliable financial reporting, and compliance with laws, regulations and policies (COSO 2013). Yet, while Otley and Soin (2014) identify both corporate governance and risk management as emerging trends within the field of management control, Speklé and Kruis (2014) find that this is not quite as simple with internal control. One of the problems for researchers and practitioners relates to the fact that the understanding of the term internal control that is institutionalized through legal requirements such as the Sarbanes–Oxley Act (SOX) of 2002 in the USA and the 2015 Audit Directive in the EU is substantially different from other official guidelines and frameworks that define internal control in a more holistic way (e.g., COSO, or the Three Lines of Defense Model).

This inconsistency between the provided frameworks and legal requirements for organizations inherently leads to various interpretations of the term in both the academic and the professional literature (Holm and Laursen 2007). Such inconsistency also leads to a potential problem for the user of the internal control reports, such as when trying to link the terminology that is used in auditors’ reports back to that which is used in the professional literature or published guidelines and standards (Boritz et al. 2013). The management control literature tends to understand the term as a ‘narrower scope definition of management control’ or the process of ‘strategy implementation’ (Merchant and Otley 2007) and thereby sees internal control as a basis of information that feeds into both the strategic control (external focus) and the management control (internal focus) systems of an organization (Pfister 2009). Other authors, however, believe that internal control is a much more holistic concept. Power (2007), for instance, states that internal control is nowadays much more an extension of risk management than an instrument of control and reaches ‘into every corner of organizational life’ (p. 63). Spira and Page (2003) similarly argue that internal control can be viewed as a ‘risk treatment’ that is increasingly institutionalized as a form of enterprise risk management. Finally, there is the literature on financial reporting (see e.g. Schneider et al. 2009), which is heavily influenced by the requirements of the SOX and therefore perceives internal control merely as a tool to assure that financial reports are of high quality, with a focus on potential material weaknesses in those reports.

Previous literature reviews on the topic of internal control have focused exclusively on the literature that relates internal control to financial reporting (Schneider et al. 2009) or internal control audits (Kinney et al. 2013) under SOX in the United States. In an attempt to provide a more comprehensive and timely understanding of the term ‘internal control,’ Chalmers et al. (2019) extend these reviews by including literature that was published in settings outside the United States. While their study provides a deeper understanding of the determinants and consequences of internal control for financial reporting on an international level, it remains limited by its focus on internal control reporting. The fact that internal control is often understood in broader terms (see e.g. Kinney 2000) justifies a literature review approach that includes research on internal control with a wider focus on the efficiency of operations. Moreover, while we know much about the potential determinants and outcomes of having an efficient internal control system, there is a lack of research on the actual practice of internal control and how managers and employees work with the system so that it actually becomes an added value for companies. Analyzing the existing literature with a deeper focus on the actual work of internal control is therefore beneficial, as it allows one to analyze how people work with internal control in practice while at the same time offering a global understanding of the term internal control. For this purpose, I argue that the theoretical lens of institutional work, as suggested by Lawrence and Suddaby (2006), will add a new perspective to the study of internal control. The theory suggests that individuals are able to create, maintain, and disrupt institutions by interacting with pressure from the institutional environment, making it possible to learn about the practice of internal control and how it is institutionalized.

The review identifies 135 studies that were published between 2000 and 2019 and focus on various aspects of the term internal control, including the relationship between internal control and enterprise risk management (ERM), its influence on audit quality, its effect on the quality of external reporting, its influence on financial innovation and on other settings, such as interorganizational relationships. While the introduction of the Sarbanes–Oxley Act has created great interest in the topic for researchers in the United States, this review identifies a wide range of studies with more international heterogeneity, especially in more recent years.

Beyond that, the review shows that the understanding of internal control is currently divided between the narrow understanding of internal control as internal control specifically over financial reporting and the more global understanding of internal control on a strategic level, which is presumably the outcome of larger institutional developments. At the same time, internal control is a practice that is executed by individual actors, who need to make sure that the controls present not only an act of compliance but an added value to their organization. Hence, the analysis of internal control through the lens of institutional work presents evidence for the different ways actors in organizations work with internal control at the micro level. This review is thus relevant for researchers, managers, policymakers, and other stakeholders who are interested in the practice of internal control.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. In the first section, I provide the reader with a more detailed introduction to the theoretical lens of institutional work. In the second, I describe the methodology of the systematic literature review that I use to categorize the literature. Third, I present and discuss the findings. Finally, I draw conclusions and offer possible directions for future research.

2 Theoretical considerations

Somewhat lost in the development of an institutional perspective has been the lived experience of organizational actors, especially the connection between this lived experience and the institutions that structure and are structured by it. (T. Lawrence et al. 2011, p. 52)

Schäffer et al. (2015) show that control systems can be perceived as ‘socially constructed patterns’ (p. 396). This has the implication that in situations of ‘institutional complexity,’ that is, situations in which actors have to deal with several institutional pressures at the same time, different organizations might respond in different ways in an attempt to not only comply with regulations but also to achieve their legitimate goals. Lawrence and Suddaby (2006) argue that this ‘institutionalization’ of activities and processes, such as internal control, is especially visible at the micro level of organization, where individuals apply the practices in their everyday work.

The theoretical perspective of institutional work invites researchers to shift their focus away from the developments that happen on the macro level of organizational fields toward the relationships between institutions and individual actors (Lawrence et al. 2011). More specifically, the original approach (Lawrence and Suddaby 2006) emphasized that the focus for the study of institutional work is, in contrast to other institutional studies, on the ways institutions are affected by action and actors (Lawrence et al. 2009). Essential for this relationship is the notion that individual actors possess agency. The idea is that these actors can critically reflect on their actions and are thus able to influence (i.e., create, maintain, and disrupt) their institutional environment through their individual actions (Lawrence and Suddaby 2006).

Being focused ‘on activity, rather than accomplishment’ (Lawrence et al. 2009, p. 11), the concept of institutional work suggests that the actors need to be reflexive about how they are embedded in the institutions and that they must possess a degree of intentionality in their actions to be able to change existing institutions. Discussing the underlying issue of agency, Emirbayer and Mische (1998) show that intentionality is the combination of three cognitive processes that are based on a temporal perspective. The first process relates to the past of the actors and describes how they are able ‘to recall, to select, and to appropriately apply the more or less tacit and taken-for-granted schemas of action that they have developed through past interactions’ (p. 975). The second process relates to the present and requires the actors to reflect critically on habits that they take for granted. Finally, the third process relates to the future-oriented intentionality, suggesting that the actors need to be able to use their experience to create solutions for complex situations in the future.

Based on such an understanding of intentionality and agency, Lawrence et al. (2009) suggest that there are two possible approaches to studying the role of the actors in institutional work. The first approach limits its scope to ‘institutional work that is motivated significantly by its potentially institutional effects’ (p. 13). In this approach, the boundaries of institutional work are narrower as it assumes that any action an actor performs unintentionally is not to be perceived as institutional work, even if it has a significant influence on institutions. In contrast, the second possible approach assumes a broader definition for institutional work, taking into account all actions that actors perform to influence institutions, whether they are intentional or not. Lawrence et al. (2009) suggest that the latter approach is too conservative, but Smets and Jarzabkowski (2013) disagree and find that actors are often engaged in institutional work without actual intentionality. The authors argue that actors can often influence institutions by performing their practical work without having critically reflected on what the ultimate consequences of their actions are. Instead, they suggest that the study of institutional work should incorporate the primary objectives of the performed work.

Lawrence et al. (2011) suggest that the key issue for studies on institutional work is to focus on the work that happens in the course of institutional change, as this can give new insights ‘into the recursive relationship between forms of institutional work and patterns of institutional change and stability’ (p. 55). To achieve this focus, Lawrence and Suddaby (2006) suggest the following taxonomy of different types of institutional work for each of the three categories of activity of creating, maintaining, and disrupting institutions (Table 1).

In light of the main arguments about institutional work presented above, I suggest that this framework is appropriate as a lens to analyze the literature that focuses on the organization and adoption of internal control, as well as how it changes, in various organizational contexts.

3 Methodology

In order to review scientific contributions in the field of internal control, I apply the methodology of a systematic literature review (SLR). According to Littell et al. (2008), systematic literature reviews aim ‘to comprehensively locate and synthesize research that bears on a particular question, using organized, transparent, and replicable procedures at each step in the process’ (p. 1). Booth et al. (2012), however, highlight the fact that comprehensiveness in systematic literature reviews does not mean to identify ‘all studies’ (p. 24) on a specific topic, since this goal is not realistic. Instead, researchers should aim to find literature that fits most appropriately with the defined topic. To achieve such a fit, Fink (2010) suggests a four-stage process toward the SLR methodology that I use to structure the paper. Using this method, I first select research questions, databases, and search terms on the topic of internal control. I then use practical screening to identify the articles that should be included or excluded from the study. Next, I systematically analyze the content of the studies through the application of a review protocol. Finally, I synthesize the findings by applying institutional work as a theoretical framework.

3.1 Stage 1: Selecting research questions, databases and search terms

In order to inquire about the main research question of the study in more detail, I suggest several sub-research questions. Because the topic of internal control is highly interdisciplinary, with many different understandings of the actual concept, I suggest a first, rather broad, sub-research question to identify these variations:

-

1.

‘What are the different meanings of internal control and how can it be defined?’

In addition to that, I suggest several generic sub-research questions that relate to the theoretical framework of this study:

-

2.

‘How is internal control institutionalized?’

-

a.

Who are the actors?

-

b.

How are internal control processes created?

-

c.

How are internal control processes maintained?

-

d.

How are internal control processes disrupted?

-

a.

-

3.

‘What do we learn from this for future research?’

To find appropriate literature on the concept of internal control, I searched the database Web of Science for the term ‘internal control’ in the title, abstract, or keywords of scientific articles in peer-reviewed journals. To ensure the quality of the findings, and in line with the methodological choices made by other researchers (e.g. Mauro et al. 2016), other types of literature, such as conference proceedings or books, have not been reviewed.

3.2 Stage 2: Applying practical screening

To identify state-of-the-art publications, I set the starting date to the year 2000, because there have been several regulatory changes for internal control afterwards, such as the introduction of the Sarbanes–Oxley Act in the United States and the Turnbull Report in the United Kingdom, which changed the role of internal control significantly. While the articles that are included in the study are selected from internationally recognized journals in a variety of disciplines, they should all focus on the topic of management control. Studies that were based on technical internal control in a medical, biological, or engineering environment were thus excluded from the study. To ensure the quality of the search results, I included only articles published in journals that are ranked level 3 or higher by the 2018 ABS Academic Journal Guide. The ABS Academic Journal Guide, however, is based in the UK and thus a certain bias toward Anglo-American research journals could be expected in its rankings. Therefore, in a second step, I also included articles published in journals that are ranked level B or higher according to the 2019 ABDC journal quality list, which is provided by the Australian business dean council. According to the official guidelines of the ABDC list, levels A and B correspond to well over 50% of the recognized journals and include both high-quality academic and more specialized, practice-oriented journals. Using these rankings, I identified 184 articles that discuss internal control in different settings. However, after a first round of screening based on the abstracts of the articles, I identified 50 articles that were not relevant for the current study, such as cases that discuss the internal locus of control for the psychology of individuals, but not internal control from a management accounting perspective. In total, this left 135 articles for analysis after the practical screening.

3.3 Stage 3: Applying methodological screening

In order to be able to analyze the content of the literature systematically, I developed a review protocol comparable to those used in previous systematic reviews (see e.g. Stechemesser and Guenther 2012). The protocol comprises three main sections. The first section holds information on the bibliographic data of the article, that is, the author(s), year, title, author(s) geographic origin, and the name of the journal that published the article. In addition, I recorded the methodology and theory (if any), as well as the country and industry (if relevant) the article analyzed. In the second section, I examined the definition of internal control and potentially any alternative terms used for the concept of internal control. If the author gave an explicit definition of internal control, I recorded this as an explicit definition. In cases when authors described internal control closely but did not directly define it, I recorded it as an implicit definition. In addition to that, I was looking for potential alternative terms that essentially describe the concept of internal control in different words. I also registered the focus and content of the studies I analyzed. Finally, I aimed to extract any information that the literature provided regarding how the actors work with and institutionalize internal control on a daily basis.

3.4 Stage 4: Synthesize the results

In line with previous systematic literature reviews (e.g. Stechemesser and Guenther 2012), I structure this final step of the literature review around the review protocol. I start by providing the reader with a brief overview of the bibliographic data and the background of the literature I analyze. I then present the findings of the content analysis and discuss them in the light of the institutional work perspective.

3.5 Bibliographic data and background of the studies

The literature review includes a total of 135 studies published between the years 2000 and 2019. Figure 1 shows several trends in the literature on internal control. Interestingly, while there are no published articles in the year 2002 when the Sarbanes–Oxley Act was introduced in the United States, the topic quickly gained momentum and reached a small peak with 14 studies appearing in the year 2009. In the wake of the global financial crisis of 2008–2009, the literature appears to have lost some interest in the topic with only 4 published studies in 2012 and 2015. However, since then the interest has grown, with 18 research studies being published in 2019. The trendline indicates that interest in the concept of internal control is clearly increasing, suggesting that research will continue to grow in the coming years.

The distribution of the geographical origin of the first author of the publication (Fig. 2) shows that the sample of articles is clearly flawed, in that that most of the authors (55%) come from the United States. Twenty-five of the studies have authors with origins in a European country. However, it also needs to be mentioned here that nine of these twenty-five authors (36%) have their origin in the UK. Hence, it is indicated that the field of internal control is strongly influenced by Anglo-Saxon accounting research traditions in line with findings of Alexander and Archer (2000). This body of literature also includes studies with first authors from China (18), Canada (4), Australia (4), Belgium (3), Finland (2), Singapore (2), South Korea (2), The Netherlands (2), Tunisia (2), and many other countries, as summed up in Fig. 2.

An analysis of the journals that publish the articles shows the interdisciplinary nature of the concept internal control. In total, the 135 articles were published in 51 different journals representing disciplines ranging from accounting and auditing to finance, business ethics, and information systems and technologies. The journals that published most of the analyzed articles are summarized in Fig. 3. The wide range of journals also suggests that there are no high-quality journals (i.e., ABS (2018) level 3 and above, or ABDC (2019) level B and above) that focus entirely on internal control issues.

Breaking down the applied methodology of the studies shows that empirical research strongly influences the literature on internal control. A substantial majority of the sample (approximately 90%) of the studies I analyzed are of an empirical nature, and can be described as economic models, case studies, surveys, or experiments. Notably, however, only a few (mostly European) studies build their reasoning on qualitative data collected either through interviews or ethnographic work. Other studies that are included in the main sample are either of a conceptual nature or present practical solutions with respect to IT systems.

Theories are not widely used in the literature on internal control and it was not possible to identify a theoretical framework in most of the studies I analyzed. For the remaining studies, and in line with the findings of previous literature reviews (Niamh and Solomon 2008), the most popular lens of analysis is Agency Theory. Besides, the studies rely on e.g., Accounting Theory, Economic Theory, Contingency Theory, and Neo-institutional Theory for their analysis. Additionally, I recorded the setting of the studies I analyzed by both countries and industries that literature has focused on. The analysis (highlighted in Fig. 4) shows that most of the publications have focused on the United States (82), China (7), The Netherlands (3) and the UK (3). In addition, there are 8 studies with an international focus and 9 studies that do not focus on a specific geographic region. The studies analyze mostly private, listed companies without specific industrial focus, since, according to SOX, such firms are, in the United States, required to report on their internal control situation, which makes it relatively simple to access the data. Studies that do focus on specific industrial settings examine the public sector (both federal and municipal), financial services, tourism, shipping, telecommunications, manufacturing, as well as religious and non-profit organizations.

4 Findings

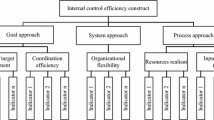

4.1 The meaning of internal control

Maijoor (2000) argues that while the research on internal controls has covered various aspects of accounting concepts on different organizational levels, it lacks structure. My review shows that this lack of structure and the limited possibility for ‘cross-fertilization’ between the different research streams is still problematic in the field. I was able to identify several different streams that analyze the concept of internal control (see Table 2 for an overview). First, there is research that discusses internal control in the light of enterprise-risk management (ERM), how it relates to it and where the differences are. Second, an abundant line of research discusses internal control with respect to auditing and what effect the introduction of the Sarbanes–Oxley Act (2002) has on both audit quality and the quality of external reporting for the firm. Third, other contemporary lines of research discuss internal control issues from the perspectives of interorganizational relationships and financial innovation.

Besides the fact that internal control is divided into different research streams in the literature, it is also certain that there is no agreement on a single definition of the concept. This appears to be mainly due to the fact that internal control has been strongly influenced by institutional pressures related to such developments as the introduction of the Sarbanes–Oxley Act and the implementation of the EU Audit Directive, as well as continuously updated versions of the COSO framework, the modernized shareholder rights directive and regulations on sustainable finance. Hence, the literature on the concept, and perhaps that of internal control as such, has developed in different directions in different geographical regions. Studies in the research streams of auditing and external reporting, for instance, are largely influenced by researchers from the United States. Here, the common agreement concerning the definition of internal control appears to be internal control over financial reporting (ICFR), meaning ‘the policies, processes, and procedures intended to ensure financial statements are reliable’ (e.g. Ashbaugh-Skaife et al. 2013, p. 91). The Sarbanes–Oxley Act required managers of companies in the United States are required to attach a report on their personal perception of the current internal control situation of the company and whether there are any weaknesses that stakeholders should be aware of. This has meant that internal control is mostly seen as a way to ensure that the financial statements that are reported by management are correct. Interestingly, there is a great variety in the use of actual terms related to internal control in the literature that has its setting in the US. Some studies do strictly adhere to the term internal control over financial reporting or ICFR (e.g. Kanagaretnam et al. 2010). Others perceive internal control as a way to have control over the reporting of financial statements, but are more liberal in their choice of terms, which may include internal control, internal control mechanism, or internal control system (e.g. Marinovic 2013; Doyle et al. 2007a; Scholten 2005).

However, while an agreement on the meaning of internal control as ICFR appears to be true for private and publicly listed companies that need to report according to SOX 404, there are indications that this might not be true for organizations in the US that do not report. For instance, writing about the issue of how internal controls might be controlled in a public sector environment, Roberts and Candreva (2006) use the much broader definition of the US Government Accountability Office (GAO) (1999). Here, internal control is defined as ‘an integral component of an organization’s management that provides reasonable assurance that the following objectives are being achieved: effectiveness and efficiency of operations, reliability of financial reporting, and compliance with applicable laws and regulations.’ Internal control in the public sector is thus not only concerned with the simple control over financial statements, but has a much more strategic aspect as it is also concerned with both the operations of the organization and compliance with current laws and regulations. Similarly, Petrovits et al. (2011) use an updated version of this definition, that exchanges ‘an integral component’ with ‘a process,’ for the analysis of internal control in nonprofit organizations. Again, in this type of organization, internal control is concerned with compliance with rules and regulations, efficiency in operations, and the reliability of financial statements.

While the literature in the United States is strongly affected by the Sarbanes–Oxley Act (2002), this is definitely not the case for the literature from authors outside of the US, where the Act does not apply. Here, internal control is rarely perceived as being solely responsible for the correct reporting of financial statements. On the contrary, the literature from the rest of the world appears to assume a much broader perspective toward the concept. While the objectives of internal control that are outlined by international frameworks, such as the COSO framework, are the same as defined by GAO, it appears that they are still broader in scope. This is due to the fact that internal control, according to COSO, concerns the whole control environment, and that a major aspect of the concept internal control is the assessment of risks. Internal control is thus closely connected to risk management. This is clearly observable from the way authors from countries outside of the US perceive internal control in their studies.

Writing about the history of internal control, accountability, and corporate governance in the UK, Jones (2008) shows that internal control is among the most important features for ensuring accountability in organizations, as well as for monitoring and controlling an organization’s operations. The author further points out that the specifics of an internal control system include both financial and non-financial controls, highlighting the holistic nature of internal control, which is closely connected to the ideas of enterprise risk management (ERM) (see also e.g. Mikes 2009). Correspondingly, from the perspective of internal auditing, Sarens et al. (2009) refer to internal control as internal control and risk management systems, indicating that the ideas of internal control and enterprise risk management (ERM) are essentially the same in practice. Similar terms have been used by Chernobai et al. (2011), who frequently refer to the concept as risk management controls or internal risk management systems.

However, while most authors from geographical regions outside of the US perceive internal control as a holistic concept that concerns the efficiency of whole organizations, exceptions to this do exist. Argyrou and Andreev (2011) argue that IT systems that companies implement to support their internal control mechanisms should be built in such a way that they ensure ‘the completeness, accuracy, and timeliness of a company’s financial reporting,’ thus stressing ICFR as the most important feature of internal control.

Interestingly, while research on internal control in the United States appears to be strongly influenced by the introduction of SOX in 2002, a similar development is now apparent outside the US, as well. Recent institutional developments, such as the integration of the EU audit directive in the national laws of its respective member states, as well as the modernized directives on shareholder rights and regulations on sustainable finance, seem to have shifted the focus of researchers outside the US toward a sense of internal control more closely related to ICFR. The following Fig. 5 depicts this change of understanding over time.

For instance, analyzing the effect that regulatory changes for internal control certification have on earnings management, Garg (2018) utilizes a unique data set from Australia. At the same time, however, the study builds on prior US studies that have their focus on financial reporting rather than a holistic understanding of internal control.

4.2 Institutionalization of internal control at the micro level

Based on these findings, it is clear that the previous literature perceives internal control from mainly two perspectives: it is used either to ensure reliable financial reporting or as a holistic mechanism that ensures the efficient operation of the whole organization. On the other hand, Woods (2009) argues that practice requires responsible actors to work with an application of the chosen control systems on a day-to-day basis. She thus states that it must be assumed that in this day-to-day application there are deviances between what the control system does in theory and how it is used in real life. In the following section, therefore, I look more closely at what we can learn from the previous literature about the practice of internal control and how individuals work with it.

4.2.1 Who are the actors?

Board of directors

In a classic paper on the failure of internal controls, Jensen (1993) states that the ‘problems with corporate control systems start with the board of directors,’ as it ‘has final responsibility for the functioning of the firm’ (p. 862). Indeed, researchers have found evidence for the importance of boards for internal control systems. Marciukaityte et al. (2006), for instance, show that if a control system has failed, restructurings in the composition of the board, e.g., through the addition of external directors, can have a positive effect on the organization’s reputation. Fresh directors give the image of a different and perhaps better corporate governance. Also Scholten (2005) finds that boards hold an important position for the institutionalization of internal control, because they can act as ‘disciplinary agents’ who can adapt the salaries and bonuses of managers, and dismiss those who do not comply with corporate policies.

In addition to that, both Monem (2011) and Chen et al. (2016) find that diversity on the board has an immediate influence on the performance of the internal control system. Discussing the importance of the board during the collapse of the Australian mobile operator One.Tel., Monem (2011) states that a major problem was a lack of diversity of opinion on the board. Instead of asking questions that might have uncovered underlying issues in the company, the board followed the management of the CEO and the organization subsequently collapsed. Chen et al. (2016) has suggested a potential solution to this problem. The author states that companies with at least one female member on the board have significantly fewer material weaknesses and more efficient operations. While the study does not identify an optimal number of female board members or determine whether male members have a positive influence at all, it suggests that females are more likely to ask the uncomfortable questions, as they tend to be fiscally more conservative and less tolerant of opportunistic behavior than their male counterparts.

At the same time, studies by Fernandez and Arrondo (2005) and Deakin and Konzelmann (2004) suggest that while the board constitutes a major actor that will be often blamed for failures, the board is not alone in the internal control system. In fact, Fernandez and Arrondo (2005) show that other internal controls can substitute for the board and that the existence of many alternatives mitigates the potential issues of one faulty type of control in the organization. Deakin and Konzelmann (2004) similarly argue that responsibility for Enron’s collapse was pinned on its board based on false merits. The authors suggest that, being non-executives, the board members were never correctly informed about the operations at the company and they lacked both knowledge and experience to be meaningfully held responsible for Enron’s fall.

However, while this indicates the importance of the board of directors as actor for the institutionalization of internal controls, the literature analyzed here indicates that several additional actors also significantly affect the internal control systems in the firm: namely, (top) management, internal auditors, and the audit committee, as well as external actors.

Top management

Analyzing the literature, it becomes evident that internal control is perceived to be largely influenced by the actions of a firm’s top management, including the CEO and the CFO of the firm. Writing about how internal controls should be controlled in a public setting, Roberts and Candreva (2006) point out that the management of an organization is ‘not only responsible for implementing internal controls to provide reasonable assurance that the agency is meeting its intended objectives, it is also responsible for self-assessing, correcting, and reporting on the efficacy of those controls’ (p. 463). Several authors highlight the importance of the whole top management team (e.g. Pernsteiner et al. 2018; Petrovits et al. 2011; Chernobai et al. 2011; Huang et al. 2009; Mikes 2009; Ashbaugh-Skaife et al. 2008; Patterson and Smith 2007; Roberts and Candreva 2006), since it possesses the necessary executive power to implement or deny changes in control systems. Moreover, top management is said to have unique interests in a firm’s well-being, especially if a significant amount of wealth is bound up in stock holdings (Chernobai et al. 2011). While this might have positive effects on the internal control system of a firm, Campbell et al. (2016) are concerned about the fact that ‘executives still make decisions whether or not to comply with reporting standards, best practices, industry norms and legislation’ (p. 271).

Other authors highlight the importance of single top managers. Wang (2010), for instance, points out that chief financial officers are likely to have superior knowledge of a firm’s internal control systems. The author posits that this poses a danger to the firm, because CFOs of organizations with weak internal control systems supposedly receive lower salaries and experience higher turnover rates than CFOs in firms with strong internal controls. CFOs are thus likely to withhold private information on internal control deficits.

More recent strands of literature discuss the CFO’s role in internal control in light of their occupational community. Campbell et al. (2016) argue that the occupational community has a positive influence on the internal control system as it relaxes the hierarchical relationship between the CEO and the CFO. They argue that CFOs may often be pressured by their hierarchical superiors and therefore tend to do things that they might perceive to be unethical. When they have a community surrounding them that faces similar issues, however, they are less likely to feel pressured. This would in turn be positive for the performance of the company and particularly the reporting of its financials. Yu et al. (2019) also show that CFOs in the high-tech industry (which is characterized by a comparably high amount of material weaknesses), the occupational community can play a decisive role in the functioning of the internal control system. These authors suggest that the CFO is actually an under-researched concept and that people holding that position should be perceived as a loosely defined group whose only common characteristic is their title. The CFO is therefore more of a role than a profession, and not all CFOs are professionals in the area of accounting. The occupational community is thus highly important for them, as they might discuss issues outside of the firm’s environment and are therefore more likely to do the right thing.

General management

In addition to top management, several authors (Wang and Hooper 2017; Kraus and Strömsten 2016; Su et al. 2014; Argyrou and Andreev 2011; Maas and Matějka 2009) point out the importance of other types of management. Writing about the control mechanisms in interorganizational relationships, for example, Kraus and Strömsten (2016) mention the importance of operational managers and how internal controls should be ‘systematically’ related to them (p. 70), as they are the personnel that work with the controls on a daily basis. In addition to that, Wang and Hooper (2017) show that, in the context of Chinese hotels, medium-level managers are able to simply outmaneuver any internal controls that are put into place by the organizational headquarters. According to the authors, this is possible because of the unique Chinese cultural context, in which it is assumed that lower-level staff will keep silent about any misconduct on the part of management. Middle managers are thus free to conduct business any way they want, including to potentially change or implement new internal controls to ensure successful business without the guidance of corporate policy.

Pernsteiner et al. (2018) explore another interesting issue: the effect of ERP systems on the internal control system of organizations. They find that managers often have to implement workarounds because the initial ERP system does not allow for special requests. Due to the system’s high costs, top management can decline improvements to the ERP system and general managers then have to find manual alternatives to solve the problem. These workarounds often lead to further workarounds and, in the end, the company is in fact using the customer as a final step of the internal control system. Such a situation can happen, for example, when a customer cancels an order. The process of billing goes through several steps in the ERP system in addition to several manual workarounds and if it is not correctly executed by the staff, the customer might be billed for a product they did not receive. If the customer notices that they have been wrongly invoiced, they then notify the company and the mistake will be fixed. The customer would thus become part of the internal control system.

Internal auditors

Another important actor in the institutionalization of internal control in organizations is the internal auditor. In a recent study of the impact of the internal audit function on the quality of internal control, Oussii and Taktak (2018) find that improving the technical competence and efficiency of the work of internal auditors has an immediate positive influence on the internal control system and contributes to more reliable financial reporting. One of the reasons for this finding is provided by Pae and Yoo (2001), who show that there is a constant tradeoff between investments in the internal control mechanisms by the owners of a given firm and the effort that is spent by auditors. The authors suggest that owners need to invest less in internal control if auditors have high legal liability and spend more effort to find any issues themselves. On the other hand, if auditors expend less effort, then owners should invest more in their internal control systems, in order to prevent irregularities. Similarly, Hunton et al. (2008) argue that a firm’s control system profits significantly from increased monitoring efforts by the internal auditing function—though the increased costs of such continuous monitoring efforts could hinder the owners of the firm from stepping up those activities.

Woods (2009) also highlights the importance of the internal audit function for internal control. Analyzing the activities that the local government in Birmingham has applied to safeguard its operations against potential risks, she mentions that risk management experts, as part of the internal audit function, were responsible for the implementation and maintenance of all of the internal control activities that the council applied. In another case study concerning four different companies in Belgium, Sarens et al. (2009) acknowledge the role of internal auditors in the functioning of internal control systems, showing that they can offer advice to both the operational staff and the audit committee. They thereby act as ‘comfort providers to the audit committee,’ which is otherwise not closely involved in the daily operations of middle management.

The audit committee

The audit committee has control over the financial reporting process, selects internal auditors, and oversees the work of both internal and external audits at a company. It should therefore have an important role in the functioning of the internal control system. Yet the evidence for this importance is twofold. On the one hand, some researchers study the effectiveness of the audit committee in light of the growing concern that the main reason for the existence of such committees is symbolic compliance with regulations, rather than fundamental oversight of the financial operations. Lisic et al. (2019), Lisic et al. (2016), and Bruynseels and Cardinaels (2014), for example, suggest that the expertise of audit committees does not automatically make the quality of the reporting process more reliable, that is, it does not mean that there will be fewer cases with reported material weaknesses. In addition to that, Lisic et al. (2016) criticize the way boards and their subcommittees (such as the audit committee), are organized in the United States. They further argue that the United States is the only country in the world that allows a CEO to be simultaneously the chairman of the board. The authors suggest that this structure allows CEOs to adversely impact the work of the boards and audit committees and to make their efforts superficial.

While previous studies indicate a rather passive role for the audit committee, there is, on the other hand, evidence that the committee holds an important function for the successful functioning of internal control systems. Krishnan (2005) found that companies with independent audit committees and great financial expertise were significantly less likely to experience internal control problems than firms with lower-quality audit committees. Naiker and Sharma (2009) also analyze the significance of the composition of the audit committee, finding that it is important to have former audit partners on the committee, even if those partners are affiliated with the firm’s external auditor. Because such former partners have significant knowledge of the operations of the firm, they are in a position to evaluate the reliability of its internal control and monitoring activities better than ‘novice auditors’ who have less knowledge of the firm.

External actors

While the previous studies stress the importance of internal actors for the institutionalization of internal control, there is also evidence for the relevance of external actors and cooperation between different actors. Analyzing interorganizational cooperation for internal control regulation in a US governmental environment, Faerman et al. (2001) find that public actors profit significantly from cooperation with managers from the private sector. The authors argue that such cooperation between the different actors has the advantage of enabling public actors to focus on the interests of the public, while relying on the greater ‘technical expertise’ of private business managers. In addition to cooperation between public-sector and private-sector actors, the authors also mention cooperation between different instances of the public sector, such as senators and the SEC, as well as guidance from union leaders who understand the practice. From the perspective of the private market in the US, Rothenberg (2009) shows that external competitors and customers can also be additional important actors. The author contents that customers will discipline a company for having weak internal controls by switching to competitors with stronger internal controls. This is inherently only possible in the United States, where management is required to report weaknesses to the public. This indicates, however, that the efforts of the US government have a very positive indirect influence on the institutionalization of strong internal controls.

One might also assume that external auditors—given that they work closely with and oversee companies—would have a significant impact on those companies’ internal control efforts. But Holm and Laursen (2007) show that internal auditors are increasingly taking over functions that used to be executed by external auditors and that the potential influence of the latter on an organization’s strategy is now largely reduced. Yet while the corporate governance debate has strengthened the internal auditor in strategic terms, there is also evidence that external auditors have an indirect influence on internal control systems. Jensen and Payne (2003), for example, show that in the setting of municipalities there is often a tradeoff situation between investing in and training an organization’s preexisting the personnel or simply hiring external auditors instead.

4.2.2 How is internal control created, maintained, or disrupted?

In their framework for institutional work, Lawrence and Suddaby (2006) suggest that actors possess a certain amount of reflexivity about and awareness of the institutions around them and are thus able to adapt them in a new and potentially better direction by either creating, maintaining, or disrupting the existing institutions. The literature on internal control describes these reflexive and purposive actions in several ways.

Creation of internal control practices

Su et al. (2014) make the case that it is difficult for actors in the current business environment to create internal control. The authors agree that actors, such as firm management, can beneficially adopt ideas from available frameworks like COSO and the more technically oriented CoBIT. Adopting ideas from these frameworks would be what T. Lawrence and Suddaby (2006) describe as mimicry, since they are widely adopted and using ideas from the frameworks can facilitate the adoption of new practices. However, there is a concern that on the practical level these frameworks do not give sufficient guidance for the actual application and design of specific tools. The actors thus need to engage in other types of work to make the institutionalization of internal control systems successful.

Given that the actors already have sufficient background knowledge about the creation of internal controls, the literature points toward some important concepts that enable actors to create successful practices. Kraus and Strömsten (2016), for instance, highlight the importance of power. In their study of the interorganizational relationship between Ericsson and Vodafone, these authors show that managers on the Vodafone side were able to coerce the supplier, Ericsson, to adopt formal internal control practices. Being one of the largest Ericsson’s largest customers, Vodafone was able to exercise a significant amount of power by threatening to switch suppliers if Ericsson did not comply with their standards. This enabled the company to transform Ericsson’s informal control system, which focused mostly on engineering, into a formal, financially oriented control system. This kind of institutional work can be related to what Lawrence and Suddaby (2006) describe as constructing normative networks. It is clear in the study that the actors on the Vodafone side showed intentionality, especially with respect to the projective future-oriented perspective, since Vodafone’s managers knew right from the start in which direction Ericsson’s the internal control system needed to develop. Through normative sanctions and compliance, they reached their goal of constructing a network with complementary internal control systems.

Other research argues that responsible actors do not need detailed knowledge for the implementation of good internal controls. From the perspective of nonprofit organizations, Petrovits et al. (2011) show that managers can receive ‘in-kind support’ from companies that donate their services to nonprofit organizations. This allows technical difficulties and questions regarding the internal control systems of an organization to be easily resolved. This kind of institutional work corresponds to Lawrence and Suddaby (2006) concept of advocacy, which involves obtaining external support ‘through direct and deliberate techniques of social suasion’ (p. 221). Petrovits et al. (2011) show that the managers of nonprofit organizations can only receive support if they can reasonably outline the need for help in improving the internal control systems. It is thus clear that the actors in this case possess intentionality both with respect to the present—since they question their current position and see the need for change—as well as with respect to projective intentionality.

Maintenance of internal control practices

One of the maintenance actions the literature describes internal control actors taking is disciplining managers. Marciukaityte et al. (2006) and Scholten (2005) both perceive internal control from the perspective of corporate governance. Marciukaityte et al. (2006) argue that actors are able to maintain the internal control mechanism of the firm by making regular changes in the composition of the board of directors. It is apparent that such changes have a positive effect on the reputation of the firm, since customers perceive fresh directors as a positive strengthening of internal control practices. Scholten (2005) similarly describes how corporate boards are able to strengthen the internal corporate governance mechanism of the firm by disciplining managers who are not complying with corporate policy. An actor can strengthen the corporate governance and internal control system of the firm by adjusting salary and bonus levels, as well as by firing any managers who pose a potential risk to the system. This kind of institutional work corresponds to what Lawrence and Suddaby (2006) identify as policing, that is, ‘ensuring compliance through enforcement, auditing and monitoring’ (p. 231).

Another important means of maintaining the internal control practices of an organization is the work of the internal audit function. In one of the cases outlined by Sarens et al. (2009), an internal auditor argues that top management is taking a more reactive than proactive approach to the internal control practices of the organization and therefore depends on the work of the internal auditor. The internal auditor meets various individuals whose work involves similar activities, but who all employ different procedures. The internal auditor needs to find a way for internal control to keep control over these. In addition to having different procedures, it also becomes apparent that several employees in that case have no real idea of internal control and risk management. Here, the internal auditor has the important function of informing the employees about the controls that are in place. Because the internal auditor acts as an authorizing agent in this case and has the role of ensuring the survival of the institution of internal control, I would argue that the kind of institutional work that the internal auditor performs can be seen as enabling work.

One way to improve the flow of information and control over various procedures is through the introduction of new IT software. Sarens et al. (2009) describe how the internal audit function was successfully able to be integrated into a formal system that was developed within the company. The system is updated on an annual basis and draws on information from several functions, including internal audit, the audit committee, and top management. In the case outlined in Woods (2009), the internal control practices were similarly maintained and gradually formalized through the introduction of a professional IT system that could process internal control and risk management issues more efficiently (see also Huang et al. (2009) for an example of a possible detecting mechanism that can aid internal control). Pernsteiner et al. (2018) likewise show that the introduction of an ERP system shifts the work of management accountants away from routine processes that can be completed by the system toward more strategic work. At the same time, their study also shows that if the ERP system is not thorough enough and top management decides to avoid pricey updates of the system, the management accountants will have to go back to their own manual ways of controlling the processes through spreadsheets. The lower-level management accountants thus need to exercise a great deal of reflection on the process that is imposed on them and find solutions to make the process work. Unfortunately, Pernsteiner et al. (2018) clearly show that the solution of having both an ERP system that is known to be faulty throughout the organization, and workaround solutions on the local level, led to a situation of chaos in the company. This highlights the importance of routinely updating the IT system in order to avoid internal control flaws. Correspondingly, Roberts and Candreva (2006) highlight the importance of constant ‘self-assessing, correcting, and reporting on the efficacy of those controls’ (p. 463), a process that the authors call ‘controlling internal controls.’ In order to achieve such ‘control over internal controls,’ the authors show that the responsible actors are constantly updating their policies and procedures. In addition to that, there is a need to train employees who are involved in the internal control process but do not possess sufficient previous knowledge on internal control (see also Woods 2009).

Both the implementation of professional IT software that improves the flow of information for internal control and risk management and the process of controlling the internal controls correspond to the institutional work of embedding and routinizing. Here, the actors introduce the ‘normative foundations of an institution into the participants’ day-to-day routines and organizational practices’ (Lawrence and Suddaby 2006, p. 233) in order to stabilize and facilitate the practice of internal control. These actors (here especially the internal auditors) show the necessary purposiveness, since the introduction of professional software as well as the process of continuous controls is not cheap for the organizations and there must be a good reason for them to engage in this kind of institutional work.

Disruption of internal control practices

Managers are able to disrupt existing internal control practices, in certain circumstances, as J. Wang and Hooper (2017) establish clearly. These authors, mentioned above, demonstrate that the hotel where the first author was employed and that belonged to a larger chain with corporate policies, in practice deviated strongly from these policies. The managers thus saw it as appropriate in certain instances to allow practices that are not tolerated by the corporate code. The authors argue, however, that due to the specific culture of the Chinese hotel industry, managers on a higher level do not have to fear that staff will mention any breach of conduct to the corporate headquarters. This is because lower level staff can be easily replaced and is therefore encouraged to keep quiet. Since the managers in this context have the belief that their actions are appropriate, this kind of action relates to the institutional work of disassociating moral foundations. Interestingly, while Lawrence and Suddaby (2006) did not find many examples of this kind of work, they believed that it is performed by elites. J. Wang and Hooper (2017) show, however, that in the Chinese cultural context it is possible even for operational managers, who are not part of any elite.

Rather surprisingly, similar evidence is also found in the setting of the strongly regulated US market. Patterson and Smith (2007), as well as Campbell et al. (2016), Yu et al. (2019) and Lisic et al. (2016) highlight the issue that top managers could simply ‘override the system of internal controls’ (Patterson and Smith 2007, p. 428), if they had the intention to commit fraud. These authors thus suggest that actors with fraudulent intentions have an inherent interest in designing weaknesses into their internal control systems. Sarbanes–Oxley punishes firms for having internal control weaknesses because such weaknesses have to be reported to the public. However, if the standards become unattainable it becomes more attractive for the firms to choose control systems that are of weaker quality. This issue is summed up in a nutshell by Soltani (2014), who analyzed the similarities between six high-profile corporate scandals in the US and Europe. The author states that ‘the ethical dilemma has been coupled with ineffective boards, inefficient corporate governance and internal control, accounting irregularities, failure of external auditors, dominant CEOs, greed and a desire for power and the lack of a sound “ethical tone at the top” policy within the organization’ (p. 270).

5 Conclusion

This literature review set out to systematically structure the literature on the topic of internal control through the application of institutional work as theoretical framework. One of the issues that was addressed is the problem of the term internal control having many different definitions, making the concept difficult to study. It was therefore my goal to find out how internal control might be defined in terms of how it is used in practice. My findings suggest that internal control currently has two different meanings based on the geographical division between the United States and the rest of the world. Strong institutional pressures in the US market (that is, the introduction of the Sarbanes–Oxley Act in 2002) has led US scholars to commonly define internal control as a mechanism to control the reliability of financial reporting, that is, internal control over financial reporting (ICFR). In markets that have experienced less regulatory pressure, internal control has developed into a broader concept that has many commonalities with related concepts such as enterprise risk management, or corporate governance. This review has thus shown that internal control in settings outside of the United States is generally perceived as a system that ensures compliance with rules and regulations and efficiency in operations, as well as assessing risk and determining the reliability of financial statements. At the same time, recent institutional changes, such as the implementation of the EU Audit Directive into the national laws of the respective member states—as well as a modernized shareholder rights directive and regulations on sustainable finance—appear to have had an impact on international research on internal control. An analysis of the time dimension also showed that researchers from outside of the US have in recent years started to focus more intensively on ICFR in the context of internal control. This leaves open the question of whether there is indeed a need for a unified holistic definition of the concept with two substantially different conceptualizations of the term. However, the fact that the term internal control or internal control system is often used interchangeably with an assumed definition of it as ICFR raises the concern that there may be potential misinterpretations in research and practice. Hence, while ICFR is a part of a holistic internal control system, it should be more clearly differentiated and identified as such.

The previous discussion on the term internal control shows the importance of strong external institutions for the development of internal control in practice. At the same time, companies need to make sure that their internal control efforts are not purely an act of formal compliance, but that they become an asset that leads to more efficient and sustainable operations. Hence, internal control is also institutionalized within organizations through the daily work of practitioners. By analyzing the literature through the theoretical lens of institutional work, I have been able to define various actors that are in practice responsible for internal control and its institutionalization within organizations. The literature on institutional work suggests that these actors institutionalize work in three ways, by creating, maintaining, and disrupting institutions. In the case of internal control, the findings indicate that these actors create the practice of internal control through the institutional work of mimicry, advocacy, and constructing normative networks. Internal control practices are maintained through policing, and enabling work. Disruption of internal control is possible for managers in organizations with weak internal control systems, or unique cultural backgrounds, where the relevance of internal control is questionable, through the institutional work of disassociating moral foundations.

This review has shown that the actors working with internal control clearly possess the purposiveness to adapt internal control practices in their specific contexts. However, several of the types of institutional work that are suggested by T. Lawrence and Suddaby (2006) could not be identified in the review. Hence, it must be assumed that while the actors in the field of internal control are reflexive and purposive, their actions are largely limited by their institutional embeddedness. At the micro level, the actors can adjust internal control so that it represents an activity that creates value for the organizations. Yet major changes in the understanding and application of internal control are achieved through institutional pressures, such as changes in legislation, which the involved actors cannot significantly influence.

The study contributes to the research on internal control in several ways. The paper presents one of the first attempts to synthesize knowledge from multiple research streams in the field beyond the conceptualization of internal control as internal control over financial reporting (ICFR). In addition to that, the application of the theoretical perspective of institutional work allowed for more in-depth analysis of the articles and therefore better insights into the actual practice of internal control. As such it adds significant new insights to the practice of internal control, in comparison with previous literature reviews on the topic, which seek to structuring the field systematically (see e.g. Chalmers et al. 2019). From a practical point of view, the study presents an aggregated understanding of the term internal control and therefore has significant practical implications, as it can supplement the efforts of regulators and practitioners to create and implement internal control procedures and frameworks that add value in the corporate governance of organizations.

5.1 Suggestions for future research

The review has shown that there is a great mixture of definitions for the concept of internal control. Several studies (e.g. Schroeder and Shepardson 2016; Marinovic 2013; Ge and McVay 2005) use the term internal control system to describe ICFR. But ICFR is only one aspect of internal control; it does not represent the entire system of controls that go into the concept. Future research should be more careful in defining the scope of research, in order to avoid false conclusions about the conceptualization and practice of internal control. At the same time, the differing conceptualizations of internal control prompt several suggestions for future research. For example, it would be interesting to investigate in greater detail why the Sarbanes–Oxley Act, as well as more recent European legislation, has been so narrowly focused around internal control over financial reporting, instead of including more holistic ideas of internal control. In addition to that, several of the papers analyzed here, which have a focus on the US market, question the role of the audit committee for the effectiveness of internal control due to the possibility of having a CEO that can simultaneously be the chairman of the board. This research could be extended in a more international context to evaluate, for example, whether audit committees are perceived as similarly superficial in jurisdictions outside of the US. This would be relevant, for example, in light of the EU Audit Directive, which requires audit committees to monitor the effectiveness of internal control, especially with regard to internal control over financial reporting.

In addition to that, the review has identified several actors in organizations who directly impact the internal control system of organizations. But we lack research on external actors who are potentially able to institutionalize the development of internal control systems in organizations. Given the identified importance of internal auditors for the institutionalization of internal control in practice, it could, for example, be interesting to explore in more detail the extent to which professional organizations such as the Institute of Internal Auditors (IIA) influence the development of internal control practices for actors at the micro level.

During the course of this research, several additional themes emerged that could be relevant to explore in future research projects. For instance, there appear to be major differences between the way compliance to internal control is perceived in certain markets, such as in China (see e.g. Wang and Hooper 2017), implying that the topic of culture holds significant value in the conceptualization and institutionalization of internal control. In this regard, it would be particularly interesting to analyze the ways cultural differences prevent organizations from implementing efficient internal controls. This review has shown that evidence is scarce for how internal controls are disrupted and how organizations can recover from situations when internal control systems have failed. Given the current development of globalization, many organizations could, in practice, profit from an increased understanding of why the same internal controls that are efficient in some regions tend to fail in others.

5.2 Limitations of the study

Like other systematic literature reviews, this study entails certain limitations. While the aim of the research methodology is to ‘comprehensively identify’ articles in the field of internal control, it needs to be acknowledged that the highly interdisciplinary nature of the field makes comprehensiveness implausible. Moreover, to limit the study to articles in the field of management control, all studies that were based on technical internal control in a medical, biological, or engineering environment were excluded. Articles that were published in languages other than English were also excluded to avoid a potential language bias. However, it is possible that the inclusion of articles in other languages would have resulted in another geographical distribution of the authors and could possibly have changed the conclusions of the study.

In addition to that, the study is limited by its methodological focus on high-quality journals ranked level 3 or higher according to the 2018 ABS list of journals or level B or higher according to the 2019 ABDC journal quality list. While the inclusion of journals that have been ranked by either the British or the Australian rankings mitigates possible regional biases, it is possible that the inclusion of more articles from journals that are ranked lower would allow for new conclusions and insights. Further literature reviews in the area of internal control with a holistic approach to the concept are thus still needed. While the current study includes professional journals in the area of financial accounting and auditing, there is room for further analysis of the potential differences between the conceptualization and institutionalization of internal control in the professional literature as compared to the academic literature.

References

References marked with * represent analyzed papers that are included in the systematic literature review.

*Abraham, S., & Cox, P. (2007). Analysing the determinants of narrative risk information in UK FTSE 100 annual reports. The British Accounting Review, 39(3), 227–248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bar.2007.06.002.

*Abrahamsen, E. B., & Aven, T. (2012). Why risk acceptance criteria need to be defined by the authorities and not the industry? Reliability Engineering & System Safety, 105, 47–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ress.2011.11.004.

*Adams, J. C., Mansi, S. A., & Nishikawa, T. (2013). Public versus private ownership and fund manager turnover. Financial Management, 42(1), 127–154. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1755-053X.2012.01220.x.

*Agyemang, G., & Broadbent, J. (2015). Management control systems and research management in universities: An empirical and conceptual exploration. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, 28(7), 1018–1046. https://doi.org/10.1108/AAAJ-11-2013-1531.

Alexander, D., & Archer, S. (2000). On the myth of “Anglo-Saxon” financial accounting. The International Journal of Accounting, 35(4), 539–557.

*Altamuro, J., & Beatty, A. (2010). How does internal control regulation affect financial reporting? Journal of Accounting and Economics, 49(1), 58–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacceco.2009.07.002.

*Argyrou, A., & Andreev, A. (2011). A semi-supervised tool for clustering accounting databases with applications to internal controls. Expert Systems with Applications, 38(9), 11176–11181.

*Armour, M. (2000). Internal control: Governance framework and business risk assessment at Reed Elsevier. Auditing, 19, 75–81.

*Ashbaugh-Skaife, H., Collins, D. W., Kinney, W. R., & LaFond, R. (2008). The effect of SOX internal control deficiencies and their remediation on accrual quality. The Accounting Review, 83(1), 217–250.

*Ashbaugh-Skaife, H., Collins, D. W., Kinney, W. R., & Lafond, R. (2009). The effect of SOX internal control deficiencies on firm risk and cost of equity. Journal of Accounting Research, 47(1), 1–43.

*Ashbaugh-Skaife, H., Veenman, D., & Wangerin, D. (2013). Internal control over financial reporting and managerial rent extraction: Evidence from the profitability of insider trading. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 55(1), 91–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacceco.2012.07.005.

*Ashfaq, K., & Rui, Z. (2019). The effect of board and audit committee effectiveness on internal control disclosure under different regulatory environments in South Asia. Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting, 17(2), 170–200. https://doi.org/10.1108/jfra-09-2017-0086.

*Baker, R. R., Biddle, G. C., Lowry, M. R., & O’Connor, N. G. (2018). Shades of gray: Internal control reporting by Chinese US-listed firms. Accounting Horizons, 32(4), 1–30. https://doi.org/10.2308/acch-52300.

*Balakrishnan, R., Matsumura, E. M., & Ramamoorti, S. (2019). Finding common ground: COSO’s control frameworks and the levers of control. Journal of Management Accounting Research, 31(1), 63–83. https://doi.org/10.2308/jmar-51891.

*Bauer, A. M. (2016). Tax avoidance and the implications of weak internal controls. Contemporary Accounting Research, 33(2), 449–486. https://doi.org/10.1111/1911-3846.12151.

*Bedard, J. C., & Graham, L. (2011). Detection and severity classifications of Sarbanes-Oxley section 404 internal control deficiencies. The Accounting Review, 86(3), 825–855.

*Benaroch, M., Chernobai, A., & Goldstein, J. (2012). An internal control perspective on the market value consequences of IT operational risk events. International Journal of Accounting Information Systems, 13(4), 357–381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.accinf.2012.03.001.

*Beneish, M. D., Billings, M. B., & Hodder, L. D. (2008). Internal control weaknesses and information uncertainty. The Accounting Review, 83(3), 665–703.

*Bhaskar, L. S., Schroeder, J. H., & Shepardson, M. L. (2019). Integration of internal control and financial statement audits: Are two audits better than one? The Accounting Review, 94(2), 53–81. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr-52197.

Bogdan, R. (2014). Aspects regarding the implementation of internal control in mining companies. Annals of the University of Petrosani: Economics, 14(1), 305–316.

Booth, A., Papioannou, D., & Sutton, A. (2012). Systematic approaches to a successful literature review. London: Sage Publications.

*Boritz, J. E., Hayes, L., & Lim, J. H. (2013). A content analysis of auditors’ reports on IT internal control weaknesses: The comparative advantages of an automated approach to control weakness identification. International Journal of Accounting Information Systems, 14(2), 138–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.accinf.2011.11.002.

*Bowrin, A. R. (2004). Internal control in Trinidad and Tobago religious organizations. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 17(1), 121–152. https://doi.org/10.1108/09513570410525238.

*Bronson, S. N., Carcello, J. V., & Raghunandan, K. (2006). Firm characteristics and voluntary management reports on internal control. Auditing, 25(2), 25–39. https://doi.org/10.2308/aud.2006.25.2.25.

Brown, K. E., & Lim, J.-H. (2012). The effect of internal control deficiencies on the usefulness of earnings in executive compensation. Advances in Accounting, incorporating Advances in International Accounting, 28(1), 75–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adiac.2012.02.006.

*Brown, N. C., Pott, C., & Wömpener, A. (2014). The effect of internal control and risk management regulation on earnings quality: Evidence from Germany. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 33(1), 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaccpubpol.2013.10.003.

*Bruynseels, L., & Cardinaels, E. (2014). The audit committee: Management watchdog or personal friend of the CEO? Accounting Review, 89(1), 113–145. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr-50601.