Abstract

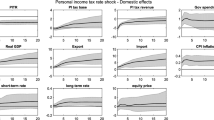

This paper examines the short- and medium-run effects of U.S. federal personal income and corporate income tax cuts on a wide array of economic policy variables in a data-rich environment. Using a panel of U.S. macroeconomic data set, made up of 132 quarterly macroeconomic series for 1959–2018, we estimate factor-augmented vector autoregression (FAVARs) models where an extended narrative tax changes dataset combined with unobserved factors. The narrative approach classifies if tax changes are exogenous or endogenous. This paper identifies narrative tax shocks in the vector autoregression model using the sign restrictions with the Uhlig's (J Monet Econ 52(2):381–419, 2005. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmoneco.2004.05.007) penalty function. Empirical findings show a significant expansionary effect of tax cuts on the macroeconomic variables. Cuts in personal and corporate income taxes cause a rise in output, investment, employment, and consumption; however, the effects of corporate tax cuts have relatively smaller effects on output and consumption but show immediate and higher effects on fixed investment and price levels. We validate the model's specification and the identification of tax shocks through a reliability test based on the Median-Target method. Additionally, sensitivity analysis employing the local projection vector autoregression model, number of iterations of the algorithm, and incorporating diverse factor specifications reaffirms tax cuts' persistent and expansionary effects. Our contribution to the narrative tax literature lies in providing empirical evidence that aligns with the notion that reductions in personal taxes demonstrate a higher efficacy as a fiscal policy tool when compared to reductions in corporate income taxes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

U.S. macroeconomic series are publically available in National Income and Product Accounts (https://apps.bea.gov/iTable/?reqid=19&step=2&isuri=1&categories=survey) and Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis website.

Code availability

Updated narrative tax changes data and the replication codes are available upon a proper request to the author.

Notes

Two recent studies, Alesina, Favero, and Giavazzi (2018) and Liu and Willaims (2019), also extend Mertens and Ravn’s (2013) narrative tax change without considering the Tax cut and Job Act (2017) and The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (2010). This study includes personal and corporate income tax liability changes from these two Acts and extends the dataset up to 2018.

The selection is based on both the Eigen value criterion of choosing the first components with eigenvalues higher than one& the amount of explained variance where chosen components should explain 70 to 80 percent of variance (King & Jackson 1999).

In an alternative estimation, I set the maximum number of factors to 20. Both PCA and ICR criteria indicate that the optimal number of factors for inclusion in the model ranges from 5 to 8. While there is a difference in the number of factors suggested by PCA and ICR, selecting the first five factors based on either criterion, out of the maximum of 20, still demonstrates that these principal components collectively account for 58% to 87% of the total variation in the dataset.

While there is a disagreement between the numbers of factors suggested by PCA and ICR, choosing the number of factors based on either PCA or ICR doesn’t imply the model misspecification since the first three to seven principal components can explain 54% to 75% of the total variance of the data (Korobilis 2009; Stock and Watson 2016).

To enhance the interpretability of the FAVAR model, we could consider adopting a more structural factor model approach. However, in line with the existing FAVAR literature, we aim to confine our interpretation of the remaining factors to serve as controls account for underlying joint macroeconomic interactions or forces, which aids in rendering the model more understandable and alleviate the concern related to ignoring the joint effects of all variables in a single model. Belviso and Milani (2006) have proposed an alternative approach involving the extraction of structural factors from groups of variables within the same economic category, as opposed to using a broad cross-section of macroeconomic time series. This approach provides factors with a more specific economic significance and facilitates a structural interpretation.

In examining the impact of an unanticipated monetary policy shock, Uhlig (2005) introduced four restrictions to isolate the shock while leaving GDP and reserves unconstrained.

Auerbach and Gorodnichenko (2013) have identified substantial variations in the magnitude of fiscal multipliers between recessions and expansions. Their findings show that tax cuts and government spending exhibit notably greater effectiveness during economic downturns compared to periods of economic expansion.

For detailed information on the construction of the military news shock and the specifics of the local projection VAR, we refer the reader to Ramey and Zubairy (2018), pages 7-18, and Jorda (2005).

Similar to the two-step method in a joint estimation framework, one can proceed to estimate the VAR model with appropriate lags using the estimated factors fac1, fac2, …, fac5, along with the narrative tax rate. Subsequently, IRFs are calculated over ℎ periods (saved in a matrix) for the five factors and the narrative tax rate in response to a shock in the narrative tax rate. Next, we need to estimate a coefficient matrix that relates the data to fac1, fac2, fac3, …, fac5, and the tax rate via Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression. This process generates a weighted matrix with the correct weights for all variables. Subsequently, one can utilize this reconstructed-weighted matrix to construct the impulse responses of all underlying variables over ℎ periods in response to a shock in the federal narrative tax rates.

References

Alesina A, Perotti R (1996) Fiscal discipline and the budget process. Am Econ Rev 86(2):401–407

Alesina A, Favero CA, Giavazzi F (2018) What do we know about the effects of austerity? AEA Pap Proc 108:524–530. https://doi.org/10.1257/pandp.20181062

Anderson E, Inoue A, Rossi B (2016) Heterogeneous consumers and fiscal policy shocks. J Money Credit Bank 48(8):1877–1888. https://doi.org/10.1111/jmcb.12366

Ando T, Tsay RS (2011) Quantile regression models with factor-augmented predictors and information criterion. Economet J 14(1):1–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1368-423X.2010.00320.x

Arias JE, Caldara D, Rubio-Ramirez JF (2019) The systematic component of monetary policy in SVARs: an agnostic identification procedure. J Monet Econ 101:1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmoneco.2018.07.011

Auerbach AJ (2002) The Bush tax cut and national saving. Natl Tax J 55(3):387–407

Auerbach AJ, Gorodnichenko Y (2013) Output spillovers from fiscal policy. Am Econ Rev 103(3):141–146. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.103.3.141

Bai J (2003) Inferential theory for factor models of large dimensions. Econometrica 71(1):135–171. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0262.00392

Bai J, Ng S (2002) Determining the number of factors in approximate factor models. Econometrica 70(1):191–221. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0262.00273

Bai J, Ng S (2006) Confidence intervals for diffusion index forecasts and inference for factor-augmented regressions. Econometrica 74(4):1133–1150. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0262.2006.00696.x

Bai J, Ng S (2007) Determining the number of primitive shocks in factor models. J Bus Econ Stat 25(1):52–60. https://doi.org/10.1198/073500106000000413

Baker SR, Bloom N, Davis SJ (2016) Measuring economic policy uncertainty. Q J Econ 131(4):1593–1636. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjw024

Banerjee A, Marcellino M, Masten I (2014) Forecasting with factor-augmented error correction models. Int J Forecast 30(3):589–612. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijforecast.2013.01.009

Belviso F, Milani F (2006) Structural factor-augmented VARs (SFAVARs) and the effects of monetary policy. Top Macroecon. https://doi.org/10.2202/1534-5998.1443

Bernanke BS, Boivin J, Eliasz P (2005) Measuring the effects of monetary policy: a factor-augmented vector autoregressive (FAVAR) approach. Q J Econ 120(1):387–422. https://doi.org/10.1162/0033553053327452

Blanchard O, Perotti R (2002) An empirical characterization of the dynamic effects of changes in government spending and taxes on output. Q J Econ 117(4):1329–1368. https://doi.org/10.1162/003355302320935043

Boivin J, Giannoni MP, Mihov I (2009) Sticky prices and monetary policy: evidence from disaggregated US data. Am Econ Rev 99(1):350–384. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.99.1.350

Breitung J, Hansen P (2021) Alternative estimation approaches for the factor augmented panel data model with small T. Empir Econ 60:327–351. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-020-01948-7

Caldara D, Kamps C (2008) What are the effects of fiscal policy shocks? A VAR-based comparative analysis. ECB Working Paper No. 877. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1102338

Candelon B, Lieb L (2013) Fiscal policy in good and bad times. J Econ Dyn Control 37:2679–2694. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jedc.2013.09.001

Canova F, De Nicolo G (2002) Monetary disturbances matter for business fluctuations in the G-7. J Monet Econ 49(6):1131–1159. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-3932(02)00145-9

Canova F, Pappa E (2011) Fiscal policy, pricing frictions and monetary accommodation. Econ Policy 26(68):555–598. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0327.2011.00272.x

Canova F, Paustian M (2011) Business cycle measurement with some theory. J Monet Econ 58(4):345–361. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmoneco.2011.07.005

Chamberlain G, Rothschild M (1983) Arbitrage, factor structure, and mean-variance analysis in large asset markets. Econometrica 51:1305–1324. https://doi.org/10.2307/1912275

Cheng X, Hansen BE (2015) Forecasting with factor-augmented regression: a frequentist model averaging approach. J Econ 186(2):280–293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeconom.2015.02.010

Cloyne J (2013) Discretionary tax changes and the macroeconomy: new narrative evidence from the United Kingdom. Am Econ Rev 103(4):1507–1528. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.103.4.1507

David MA, Sever C (2023) Unpleasant Surprises? Elections and tax news shocks. International Monetary Fund. Working Paper No. 2023/139

Doz C, Fuleky P (2020) Dynamic factor models. Macroecon Forecast Era Big Data Theory Pract 8:27–64. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-31150-6

Dungey M, Fry R (2009) The identification of fiscal and monetary policy in a structural VAR. Econ Model 26(6):1147–1160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2009.05.001

Eickmeier S, Lemke W, Marcellino M (2015) Classical time varying factor-augmented vector auto-regressive models—estimation, forecasting and structural analysis. J R Stat Soc Ser A Stat Soc 178(3):493–533. https://doi.org/10.1111/rssa.12068

Evans OJ (1983) Tax policy, the interest elasticity of saving, and capital accumulation: numerical analysis of theoretical models. Am Econ Rev 73(3):398–410

Fair RC (1986) Evaluating the predictive accuracy of models. Handb Econ 3:1979–1995. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1573-4412(86)03013-1

Fatás A, Mihov I (2001) Government size and automatic stabilizers: international and intranational evidence. J Int Econ 55(1):3–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-1996(01)00093-9

Faust J (1998) The robustness of identified VAR conclusions about money. In: Carnegie-Rochester conference series on public policy, vol 49. North-Holland. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0167-2231(99)00009-3

Forni M, Gambetti L (2010) The dynamic effects of monetary policy: a structural factor model approach. J Monet Econ 57(2):203–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmoneco.2009.11.009

Forni M, Giannone D, Lippi M, Reichlin L (2009) Opening the black box: structural factor models with large cross sections. Economet Theor 25:1319–1347. https://doi.org/10.1017/S026646660809052X

Fry R, Pagan A (2011) Sign restrictions in structural vector autoregressions: a critical review. J Econ Lit 49(4):938–960. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.49.4.938

Furlanetto F, Ravazzolo F, Sarferaz S (2019) Identification of financial factors in economic fluctuations. Econ J 129(617):311–337. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecoj.12520

Gale WG, Samwick AA (2014) Effects of income tax changes on economic growth. Econ Stud. Retrieved from https://www.brookings.edu/wpcontent/uploads/2016/06/09_Effects_Income_Tax_Changes_Economic_Growth_Gale_Samwick.pdf

Gale WG, Orszag PR (2005) Economic effects of making the 2001 and 2003 tax cuts permanent. Int Tax Public Financ 12(2):193–232. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10797-005-0494-8

Geweke JF, Singleton KJ (1981) Maximum likelihood “confirmatory” factor analysis of economic time series. Int Econ Rev 8:37–54. https://doi.org/10.2307/2526134

Giannone D, Reichlin L, Small D (2008) Nowcasting: the real-time informational content of macroeconomic data. J Monet Econ 55(4):665–676. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmoneco.2008.05.010

Giavazzi F, Pagano M (1990) Can severe fiscal contractions be expansionary? Tales of two small European countries. NBER Macroecon Ann 5:75–111. https://doi.org/10.1086/654131

Gilchrist S, Sim JW, Zakrajšek E (2014) Uncertainty, financial frictions, and investment dynamics (No. w20038). National Bureau of Economic Research. https://doi.org/10.3386/w20038

Gonçalves S, Perron B (2014) Bootstrapping factor-augmented regression models. J Economet 182(1):156–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeconom.2014.04.015

Harvey AC, Jaeger A (1993) Detrending, stylized facts and the business cycle. J Appl Economet 8(3):231–247. https://doi.org/10.1002/jae.3950080302

Hassett KA, Metcalf GE (1999) Investment with uncertain tax policy: does random tax policy discourage investment. Econ J 109(457):372–393. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0297.00453

Hepenstrick C, Marcellino M (2016) Forecasting with large unbalanced datasets: the mixed frequency three-pass regression filter (No. 2016-04). Swiss National Bank

Hodrick RJ, Prescott EC (1997) Postwar US business cycles: an empirical investigation. J Money Credit Bank 29:1–16. https://doi.org/10.2307/2953682

Ihori T (1997) Taxes on capital accumulation and economic growth. J Macroecon 19(3):509–522. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0164-0704(97)00026-8

Jordà Ò (2005) Estimation and inference of impulse responses by local projections. Am Econ Rev 95(1):161–182. https://doi.org/10.1257/0002828053828518

Kaldor N (1961) Capital accumulation and economic growth. In: The theory of capital: proceedings of a conference held by the International Economic Association. Palgrave Macmillan UK, London, pp 177–222. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-08452-4_10

Kilian L (1998) Small-sample confidence intervals for impulse response functions. Rev Econ Stat 80(2):218–230. https://doi.org/10.1162/003465398557465

King JR, Jackson DA (1999) Variable selection in large environmental data sets using principal components analysis. Environmetrics 10(1):67–77. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-095X(199901/02)10:1%3C67::AID-ENV336%3E3.0.CO;2-0

Korobilis D (2009) Assessing the transmission of monetary policy shocks using dynamic factor models. Retrieved from https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1461152

Kunze, L. (2010). Capital taxation, long-run growth, and bequests. Journal of Macroeconomics, 32(4), 1067–1082.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmacro.2010.06.008

Lagana G, Mountford A (2005) Measuring monetary policy in the UK: a factor-augmented vector autoregression model approach. Manch Sch 73:77–98. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9957.2005.00462.x

Leeper EM, Richter AW, Walker TB (2012) Quantitative effects of fiscal foresight. Am Econ J Econ Pol 4(2):115–144. https://doi.org/10.1257/pol.4.2.115

Liu C, Williams N (2019) State-level implications of federal tax policies. J Monet Econ 105:74–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmoneco.2019.04.005

Lombardi MJ, Osbat C, Schnatz B (2012) Global commodity cycles and linkages: a FAVAR approach. Empir Econ 43:651–670. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-011-0494-8

Mangadi K, Sheen J (2017) Identifying terms of trade shocks in a developing country using a sign restrictions approach. Appl Econ 49(24):2298–2315. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2016.1237757

Marcellino M (2017) An introduction to factor modelling. centro de estudios monetarios latinoamericanos (CEMLA) webinar session lecture slides Bocconi University. Available at https://www.cemla.org/PDF/webinars/2017-05-MARCELLINOMASSIMILIANO.pdf

McCracken MW, Ng S (2016) FRED-MD: a monthly database for macroeconomic research. J Bus Econ Stat 34(4):574–589. https://doi.org/10.1080/07350015.2015.1086655

Mertens K, Ravn MO (2013) The dynamic effects of personal and corporate income tax changes in the United States. Am Econ Rev 103(4):1212–1247. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.103.4.1212

Mountford A, Uhlig H (2009) What are the effects of fiscal policy shocks? J Appl Economet 24(6):960–992. https://doi.org/10.1002/jae.1079

Ouliaris S, Pagan AR, Restrepo J (2015) A new method for working with sign restrictions in SVARs. National Centre for Econometric Research, No. 105

Pappa E (2009) The effects of fiscal shocks on employment and the real wage. Int Econ Rev 50(1):217–244. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2354.2008.00528.x

Paustian M (2007) Assessing sign restrictions. BE J Macroecon. https://doi.org/10.2202/1935-1690.1543

Perotti R, Reis R, Ramey V (2007) In search of the transmission mechanism of fiscal policy. NBER Macroecon Ann 22:169–249. https://doi.org/10.1086/ma.22.25554966

Ramey VA, Zubairy S (2018) Government spending multipliers in good times and in bad: evidence from US historical data. J Polit Econ 126(2):850–901. https://doi.org/10.1086/696277

Romer CD, Romer DH (2009) A narrative analysis of postwar tax changes. Unpublished paper, University of California, Berkeley (June). Retrieved from https://eml.berkeley.edu/~dromer/papers/nadraft609.pdf

Romer CD, Romer DH (2010) The macroeconomic effects of tax changes: estimates based on a new measure of fiscal shocks. Am Econ Rev 100(3):763–801. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.100.3.763

Rubio-Ramírez JF, Waggoner DF, Zha T (2010) Structural vector autoregressions: theory of identification and algorithms for inference. Rev Econ Stud 77(2):665–696. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-937X.2009.00578.x

Sargent TJ, Sims CA (1977) Business cycle modeling without pretending to have too much a priori economic theory. New Methods Bus Cycle Res 1:145–168. https://doi.org/10.21034/wp.55

Smith RP, Zoega G (2005) Unemployment, investment and global expected returns: a panel FAVAR approach. Birkbeck Working Papers in Economics and Finance 0524, Birkbeck. Department of Economics, Mathematics & Statistics. Available at https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1726817

Stock JH, Watson MW (2005) Implications of dynamic factor models for VAR analysis. National Bureau of Economic Research. No. w11467. https://doi.org/10.3386/w11467

Stock JH, Watson MW (2012) Disentangling the channels of the 2007–2009 recession. National Bureau of Economic Research. No. w18094. https://doi.org/10.3386/w18094

Stock JH, Watson MW (2016) Dynamic factor models, factor-augmented vector autoregressions, and structural vector autoregressions in macroeconomics. In: Handbook of macroeconomics (chapter 8). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.hesmac.2016.04.002

Stock JH, Watson MW (2002) Forecasting using principal components from a large number of predictors. J Am Stat Assoc 97(460):1167–1179. https://doi.org/10.1198/016214502388618960

Stock JH, Watson MW (2018) Identification and estimation of dynamic causal effects in macroeconomics using external instruments. Econ J 128(610):917–948. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecoj.12593

The Protection P, Act AC (2010) Patient protection and affordable care act. Public Law 111(48):759–762. Retrieved from https://www.connectthedotsusa.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/ACAvNIMASlidesScript_6_3_19.pdf

Uhlig H (2005) What are the effects of monetary policy on output? Results from an agnostic identification procedure. J Monet Econ 52(2):381–419. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmoneco.2004.05.007

Westerlund J, Urbain JP (2013) On the estimation and inference in factor-augmented panel regressions with correlated loadings. Econ Lett 119(3):247–250. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2013.03.022

Acknowledgements

I extend my gratitude to Professor Jeremy R. Groves (for his excellent supervision), Prof. Carl Campbell, Prof. Ai-ru (Meg) Cheng and Prof. Alexander Garivaltis for their support and valuable feedback during my research at Northern Illinois University. I am thankful to the two anonymous referees and Professor Joakim Westerlund, the editor-in-chief, for their contributions to this manuscript. Special thanks to the participants of the Illinois Economics Association 49th annual meeting at DePaul University, Chicago, for their insightful comments. I also acknowledge the support from the SUST Research Center's research grant for additional data analysis during the revision stage.

Funding

No funding was received for conducting this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

There is no potential financial or non-financial conflicts of interest related to this study. I declare that I have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix

Extension of the narrative dataset

2.1 I. The Tax Relief, Unemployment Insurance Reauthorization, and Job Creation Act of 2010

On December 10, 2010, President Barack Obama signed the Tax Relief, Unemployment Insurance Reauthorization, and Job Creation Act, commonly referred to as the Relief Act 2010. This legislation aimed to provide essential tax relief to American workers and encourage investments that could generate employment opportunities and spur economic growth. Many of the components of the Relief Act involved extending existing tax relief measures through 2011. For instance, Title I addressed the Temporary Extension of Tax Relief, Title II focused on the Temporary Extension of Individual AMT Relief, Title III dealt with Temporary Estate Tax Relief, and Title IV pertained to the Temporary Extension of Investment Incentives. Among the various tax extensions and modifications, the most noteworthy change concerning income tax liability was found in Title VI, known as the Temporary Employee Payroll Tax Cut. Title VI aimed to reduce the payroll tax by 2 percent, necessitating a transfer of revenue from the Treasury to various social security trust funds to compensate for the anticipated loss in revenue. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimated that this revenue change, as detailed in S.A. 4753, an amendment to H.R. 4853, would amount to − 67.239 billion dollars (source: https://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/111th-congress-2009-2010/costestimate/sa47530.pdf). Following Mertens and Ravn's methodology (2013), it was determined that the change in income tax liability in the first quarter of 2011 was − 67.239 billion dollars. It's noteworthy that there were no changes in tax liability associated with corporate taxes. Specifically, Subtitle C of the Act only extended fifteen business tax relief measures through 2011.

Total revenue effects in 2011 related to income tax liability = − 67.239 billion.

Personal taxable income in 2010: 11,236.2 billion.

Narrative personal income tax rate in 2011Q1: (− 67.239bn /11236.2bn) *100 = − 0.5877 percent.

2.2 The American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012 and the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act 2010

The American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012

In 2012, the American Taxpayer Relief Act (ATRA) played a pivotal role in addressing the U.S. "fiscal cliff" issue and officially came into effect on January 1, 2013. This legislation represented a bipartisan budget compromise measure and introduced several modifications to the tax code. These changes had a direct impact on the long-term fiscal outlook of the United States and encompassed alterations to both individual and corporate income tax responsibilities. The key provisions of the 2012 ATRA pertaining to personal and corporate income taxes included the reinstatement of tax deductions and credits for individuals and couples, the allowance for deductions related to contributions of food inventory by taxpayers, the deduction for income associated with domestic production activities in Puerto Rico, the reduction of built-in gains for S corporations, and tax incentives designed to encourage investment in empowerment zones. According to the Congressional Budget Office's (CBO) estimate for 2013 (source: https://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/112th-congress-2011-2012/costestimate/american-taxpayer-relief-act0.pdf), the American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012, which was enacted on January 1, 2013, had revenue effects of − 5.901 billion dollars due to changes in individual income taxes (Title II) and − 63.033 billion dollars due to changes in corporate income taxes (Title III).

Total revenue effects in 2013 related to personal income tax changes = -5.901 billion.

Personal taxable income in 2012: 12,620. 8 billion.

Narrative personal income tax rate: (− 5.901 bn/12620.8 bn) *100 = − 0.046 percent.

Total revenue effects in 2013 related to corporate income tax changes = − 63.033 billion.

Corporate taxable income in 2012: 1925.7 billion.

Narrative corporate income tax rate: (− 63.033 billion /1925.7 bn) *100 = − 3.27 percent.

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act 2010

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA), commonly known as Obamacare, was enacted in March 2010 and signed into law on March 23, 2010. Its primary objective was to make health insurance more affordable and accessible to a broader segment of the American population. To finance the ACA's provisions, several tax changes were implemented. The ACA raised personal income tax rates by 0.9 percent on individual wages exceeding specific income thresholds. Additionally, it introduced a 3.8 percent increase in the net investment income tax for both individuals and corporations. Most of the ACA's tax provisions took effect either in January 2013 or 2014. Projections regarding the revenue impact of the ACA were uncertain because they relied heavily on forecasts related to the ACA's provisions and tax code alterations' implementation. The provision of coverage and the implementation of taxes were also marked by considerable uncertainty. In accordance with the criteria set forth by Mertens and Ravn (2013), the incorporation of tax provisions from the Affordable Care Act (ACA) into our dataset raises concerns regarding anticipation effects, given that the time gap between policy announcement and implementation dates exceeds 90 days. Nevertheless, adhering to the exogenity approach outlined by Romer and Romer (2009), we classify ACA's tax code changes as inherently exogenous due to their ideological motivations.

Furthermore, the implementation of the Affordable Care Act, commonly known as Obamacare, encountered uncertainties and challenges even after being signed into law in 2010. Ongoing opposition from specific political factions persisted, resulting in legal and political challenges. Some adversaries sought to repeal or undermine the legislation, generating uncertainty about its future and even the possibility of its full implementation. Given the uncertainty surrounding the ACA's future implementation, we presume a minimal anticipation effect and consequently include the associated tax code changes in 2013.

In March 2010, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) and the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) estimated that the enactment of the ACA (H.R. 6079) could lead to a net reduction in federal budget deficits of $143 billion over the period of 2010–2019 (source: testimony delivered by CBO’s Director on March 30, 2011; https://www.cbo.gov/publication/45447). Although the revenue effects were predominantly linked to increased income tax rates on individual wages and the net investment income tax, specific information about the revenue attributable to personal and corporate income tax changes was not available. Consequently, this study apportions the entire $4 billion in revenue using the proportion of personal and corporate income tax revenue's share in the total increased revenue for 2013.

According to the CBO’s updated budget analysis, individual income tax revenue increased by $184.2 billion, while corporate tax revenue increased by $31 billion in 2013 (source: https://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/113th-congress-2013-2014/reports/45010-outlook2014feb0.pdf, p. 9–10). The contribution of individual income tax to the total revenue was calculated as 85 percent (184.2/184.2 + 31), and corporate tax accounted for 15 percent. This resulted in a revenue effect related to personal income tax liability changes of $3.4 billion and $0.6 billion for the corporate tax liability change. These figures are utilized in this study to compute the narrative tax rates associated with the ACA act.

Revenue change related to the personal income tax change in 2013: 3.4 billion.

Personal taxable income in 2012: 12,620.8 bn.

Narrative PI tax rate: 3.4 bn /12620. 8 bn = 0.0269 percent.

The revenue change related to the CI tax change in 2013 was 0.6 billion.

Corporate taxable income in 2012: 1925.7 bn.

Narrative CI tax rate: 0.6 billion /1925.7 bn = 0.0.0311 percent.

2.3 The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) of 2017 brought significant changes to individual and corporate income tax liabilities and introduced numerous amendments to existing U.S. tax laws. It entailed reductions in individual income taxes across all income tax brackets and streamlined the top corporate tax rate from 35 percent to a single, flat rate of 20 percent. Additionally, the TCJA established a maximum rate of 25 percent for corporations and businesses. The legislation also doubled nearly all child tax credits and increased the standard deduction. According to the Joint Committee on Taxation's (JCT) estimation, the TCJA was expected to have a revenue impact of approximately $1,438 billion over the period from 2018 to 2027 (source: https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/115th-congress-2017-2018/costestimate/hr1.pdf, p. 2).

In terms of specific revenue figures for 2018, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) baseline budget projections indicated revenue estimates of -65 billion dollars for personal income taxes and -94 billion dollars for corporate income taxes (source: https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2019-04/53651-outlook-2.pdf, p. 94, Table A-1).

Revenue change related to the personal income tax change in 2018 was: − 65 billion.

Personal taxable income in 2017: 15,420.8 bn.

Narrative personal tax rate: − 65 bn /15420.8 bn = − 0.4163 percent.

Revenue change related to the corporate income tax change in 2018 was: − 94 billion.

Corporate taxable income in 2017: 2036.3 bn.

Narrative corporate income tax rate: − 94 billion/2036.3 bn = − 4.61 percent.

II. List of narrative tax changes (1950–2018)

Tax code/changes | Narrative PIT | Narrative CIT |

|---|---|---|

Internal Revenue Code of 1954 | √ | √ |

Changes in Depreciation Guidelines and Revenue Act of 1962 (Two corporate tax liability has changed in quarter 2 and 3) | No | √ |

Revenue Act of 1964 | √ | √ |

Public Law 90–26 (Restoration of the Investment Tax Credit) 1967 | No | √ |

Reform of Depreciation Rules 1971 (only corporate tax liability changed in quarter 1) Revenue Act of 1971 (Both personal income tax and corporate tax liability changed in quarter 4) | √ | √ |

Tax Reform Act of 1976 | √ | √ |

Tax Reduction and Simplification Act of 1977 | √ | √ |

Revenue Act of 1978 | √ | √ |

Economic Recovery Tax Act of 1981 | √ | √ |

Deficit Reduction Act of 1984 | √ | √ |

Tax Reform Act of 1986 | √ | √ |

Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1987 | √ | √ |

Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1990 | √ | √ |

Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1993 | √ | No |

Jobs and Growth Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2003 | √ | √ |

The Tax Relief, Unemployment Insurance Reauthorization, and Job Creation Act of 2010 | √ | No |

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act 2010 | √ | √ |

The American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012 | √ | √ |

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 | √ | √ |

III. List of narrative tax changes announcement and effective dates (1950–2018)

Tax code/changes | Announcement Date | Effective as Law (Signed into law by President) |

|---|---|---|

Internal Revenue Code of 1954 | March 9, 1954 | August 16, 1954 |

Changes in Depreciation Guidelines and Revenue Act of 1962 (Two corporate tax liability has changed in quarter 2 and 3) | May 10, 1962 | Oct 16, 1962 |

Revenue Act of 1964 | January 1963 | February 26, 1964 |

Public Law 90-26 (Restoration of the Investment Tax Credit) 1967 | March 9, 1967 | June 13, 1967 |

Reform of Depreciation Rules 1971 (only corporate tax liability changed in quarter 1) Revenue Act of 1971 (Both personal income tax and corporate tax liability changed in quarter 4) | January 26, 1971 | January 19, 1972 |

Tax Reform Act of 1976 | September 1976 | October 4, 1976 |

Tax Reduction and Simplification Act of 1977 | February 16, 1977 | May 23, 1977 |

Revenue Act of 1978 | July 1978 | November 6, 1978 |

Economic Recovery Tax Act of 1981 | July 23, 1981 | August 13, 1981 |

Deficit Reduction Act of 1984 | Oct 1983 | July 18, 1984 |

Tax Reform Act of 1986 | December 3, 1985 | October 22, 1986 |

Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1987 | Oct 1987 | December 22, 1987 |

Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1990 | Oct 1990 | November 5, 1990 |

Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1993 | May 25, 1993 | August 10, 1993 |

Jobs and Growth Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2003 | February 27, 2003 | May 28, 2003 |

The Tax Relief, Unemployment Insurance Reauthorization, and Job Creation Act of 2010 | March 16, 2010 | December 17, 2010 |

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act 2010 | September 17, 2009 | March 23, 2010 |

The American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012 | July 24, 2012 | January 2, 2013 |

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 | November 2, 2017 | January 1, 2018 |

IV. List of macroeconomic variables

5.1 Group 1: National income and product accounts (NIPA)

-

1.

Real Gross Domestic Product, 3 Decimal (Billions of Chained 2012 Dollars)

-

2.

Consumption Real Personal Consumption Expenditures (Billions of Chained 2012 Dollars)

-

3.

Real personal consumption expenditures: Durable goods (Billions of Chained 2012 Dollars)

-

4.

Real Personal Consumption Expenditures: Services (Billions of 2012 Dollars),

-

5.

Real Personal Consumption Expenditures: Nondurable Goods (Billions of 2012 Dollars)

-

6.

Investment Real Gross Private Domestic Investment, (Billions of Chained 2012Dollars)

-

7.

Real private fixed investment (Billions of Chained 2012 Dollars)

-

8.

Real Gross Private Domestic Investment: Fixed Investment: Nonresidential: Equipment (Billions of Chained 2012 Dollars)

-

9.

Real private fixed investment: Nonresidential (Billions of Chained 2012 Dollars)

-

10.

Real private fixed investment: Residential (Billions of Chained 2012 Dollars)

-

11.

Shares of gross domestic product: Gross private domestic investment: Change in private inventories (Percent)

-

12.

Real Government Consumption Expenditures & Gross Investment (Billions of Chained 2012 Dollars)

-

13.

Real Government Consumption Expenditures and Gross Investment: Federal (Percent Change from Preceding Period)

-

14.

Real Gov Receipts Real Federal Government Current Receipts (Billions of Chained 2012 Dollars)

-

15.

Real government state and local consumption expenditures (Billions of Chained 2012 Dollars)

-

16.

Real Exports of Goods & Services (Billions of Chained 2012 Dollars)

-

17.

Real Imports of Goods & Services (Billions of Chained 2012 Dollars)

-

18.

Real Disposable Personal Income (Billions of Chained 2012 Dollars)

-

19.

Nonfarm Business Sector: Real Output (Index 2012 = 100)

-

20.

Business Sector: Real Output (Index 2012 = 100)

-

21.

Manufacturing Sector: Real Output (Index 2012 = 100)

5.2 Group 2: Industrial production

-

1.

Industrial Production Index (Index 2012 = 100)

-

2.

Industrial Production: Final Products (Market Group) (Index 2012 = 100)

-

3.

Industrial Production: Consumer Goods (Index 2012 = 100)

-

4.

Industrial Production: Materials (Index 2012 = 100)

-

5.

Industrial Production: Durable Materials (Index 2012 = 100)

-

6.

Industrial Production: Nondurable Materials (Index 2012 = 100)

-

7.

Industrial Production: Durable Consumer Goods (Index 2012 = 100)

-

8.

Industrial Production: Durable Goods: Automotive products (Index 2012 = 100)

-

9.

Industrial Production: Nondurable Consumer Goods (Index 2012 = 100)

-

10.

Industrial Production: Business Equipment (Index 2012 = 100)

-

11.

Industrial Production: Consumer energy products (Index 2012 = 100)

-

12.

Capacity Utilization: Total Industry (Percent of Capacity)

-

13.

Capacity Utilization: Manufacturing (SIC) (Percent of Capacity)

-

14.

Industrial Production: Manufacturing (SIC) (Index 2012 = 100)

-

15.

Industrial Production: Residential Utilities (Index 2012 = 100)

-

16.

Industrial Production: Fuels (Index 2012 = 100)

5.3 Group 3: Employment and unemployment

-

1.

All Employees: Total nonfarm (Thousands of Persons)

-

2.

All Employees: Total Private Industries (Thousands of Persons)

-

3.

All Employees: Manufacturing (Thousands of Persons)

-

4.

All Employees: Service-Providing Industries (Thousands of Persons)

-

5.

All Employees: Goods-Producing Industries (Thousands of Persons)

-

6.

All Employees: Durable goods (Thousands of Persons)

-

7.

All Employees: Nondurable goods (Thousands of Persons)

-

8.

All Employees: Construction (Thousands of Persons)

-

9.

All Employees: Education & Health Services (Thousands of Persons)

-

10.

All Employees: Financial Activities (Thousands of Persons)

-

11.

All Employees: Information Services (Thousands of Persons)

-

12.

All Employees: Professional & Business Services (Thousands of Persons)

-

13.

All Employees: Leisure & Hospitality (Thousands of Persons)

-

14.

All Employees: Other Services (Thousands of Persons)

-

15.

All Employees: Mining and logging (Thousands of Persons)

-

16.

All Employees: Trade, Transportation & Utilities (Thousands of Persons)

-

17.

All Employees: Government (Thousands of Persons)

-

18.

All Employees: Retail Trade (Thousands of Persons)

-

19.

All Employees: Wholesale Trade (Thousands of Persons)

-

20.

All Employees: Government: Federal (Thousands of Persons)

-

21.

All Employees: Government: State Government (Thousands of Persons)

-

22.

All Employees: Government: Local Government (Thousands of Persons)

-

23.

Civilian Employment (Thousands of Persons)

-

24.

Civilian Labor Force Participation Rate (Percent)

-

25.

Civilian Unemployment Rate (Percent)

-

26.

Business Sector: Hours of All Persons (Index 2012 = 100)

-

27.

Manufacturing Sector: Hours of All Persons (Index 2012 = 100)

-

28.

Nonfarm Business Sector: Hours of All Persons (Index 2012 = 100)

-

29.

Average Weekly Hours of Production and Nonsupervisory Employees: Manufacturing (Hours)

-

30.

Weekly Hours of Production and Nonsupervisory Employees: Total private (Hours)

-

31.

Help-Wanted Index

5.4 Group 4: Housing

-

1.

Housing Starts: Total: New Privately Owned Housing Units Started (Thousands of Units)

-

2.

Housing Starts: 5-Unit Structures or More (Thousands of Units)

-

3.

New Private Housing Units Authorized by Building Permits (Thousands of Units)

-

4.

Housing Starts in Midwest Census Region (Thousands of Units)

-

5.

Housing Starts in Northeast Census Region (Thousands of Units)

-

6.

Housing Starts in South Census Region (Thousands of Units)

-

7.

Housing Starts in West Census Region (Thousands of Units)

-

8.

All-Transactions House Price Index for the United States (Index 1980 Q1 = 100)

-

9.

S&P/Case-Shiller 10-City Composite Home Price Index (Index January 2000 = 100)

-

10.

S&P/Case-Shiller 20-City Composite Home Price Index (Index January 2000 = 100)

5.5 Group 5: Prices

-

1.

Personal Consumption Expenditures: Chain-type Price Index (Index 2012 = 100)

-

2.

Personal Consumption Expenditures Excluding Food and Energy (Chain-Type Price Index) (Index 2012 = 100)

-

3.

Gross Domestic Product: Chain-type Price Index (Index 2012 = 100)

-

4.

Gross Private Domestic Investment: Chain-type Price Index (Index 2012 = 100)

-

5.

Business Sector: Implicit Price Deflator (Index 2012 = 100)

-

6.

Personal consumption expenditures: Goods (chain-type price index)

-

7.

Personal consumption expenditures: Durable goods (chain-type price index)

-

8.

Personal consumption expenditures: Services (chain-type price index)

-

9.

Personal consumption expenditures: Nondurable goods (chain-type price index)

-

10.

Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers: All Items (Index 1982–84 = 100)

-

11.

Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers: All Items Less Food & Energy (Index 1982–84 = 100)

-

12.

Producer Price Index by Commodity for Finished Goods (Index 1982 = 100)

-

13.

Producer Price Index for All Commodities (Index 1982 = 100)

5.6 Group 6: Earnings and productivity

-

1.

Real Average Hourly Earnings of Production and Nonsupervisory Employees: Total Private (2012 Dollars per Hour)

-

2.

Real Average Hourly Earnings of Production and Nonsupervisory Employees: Construction (2012 Dollars per Hour)

-

3.

Real Average Hourly Earnings of Production and Nonsupervisory Employees: Manufacturing (2012 Dollars per Hour)

-

4.

Nonfarm Business Sector: Real Compensation Per Hour (Index 2012 = 100)

-

5.

Business Sector: Real Compensation Per Hour (Index 2012 = 100)

-

6.

Manufacturing Sector: Real Output Per Hour of All Persons (Index 2012 = 100)

-

7.

Nonfarm Business Sector: Real Output Per Hour of All Persons (Index 2012 = 100)

-

8.

Business Sector: Real Output Per Hour of All Persons (Index 2012 = 100)

-

9.

Business Sector: Unit Labor Cost (Index 2012 = 100)

-

10.

Manufacturing Sector: Unit Labor Cost (Index 2012 = 100)

-

11.

Nonfarm Business Sector: Unit Labor Cost (Index 2012 = 100)

5.7 Group 7: Interest rates

-

1.

Effective Federal Funds Rate (Percent)

-

2.

3-Month Treasury Bill: Secondary Market Rate (Percent)

-

3.

6-Month Treasury Bill: Secondary Market Rate (Percent)

-

4.

1-Year Treasury Constant Maturity Rate (Percent)

-

5.

10-Year Treasury Constant Maturity Rate (Percent)

-

6.

30-Year Conventional Mortgage Rate© (Percent)

-

7.

Moody’s Seasoned Aaa Corporate Bond Yield© (Percent)

-

8.

Moody’s Seasoned Baa Corporate Bond Yield© (Percent)

5.8 Group 8: Money and credit

-

1.

St. Louis Adjusted Monetary Base (Billions of 1982–84 Dollars)

-

2.

Real Institutional Money Funds (Billions of 2012 Dollars)

-

3.

Real M1 Money Stock (Billions of 1982–84 Dollars)

-

4.

Real M2 Money Stock (Billions of 1982–84 Dollars)

-

5.

Total Reserves of Depository Institutions (Billions of Dollars)

-

6.

Reserves of Depository Institutions, Nonborrowed (Millions of Dollars)

5.9 Group 9: Household balance sheets

-

1.

Real Total Assets of Households and Nonprofit Organizations (Billions of 2012 Dollars)

-

2.

Real Total Liabilities of Households and Nonprofit Organizations (Billions of 2012 Dollars)

-

3.

Liabilities of Households and Nonprofit Organizations Relative to Personal Disposable Income (Percent)

-

4.

Real Estate Assets of Households and Nonprofit Organizations (Billions of 2012 Dollars)

-

5.

Real Total Financial Assets of Households and Nonprofit Organizations (Billions of 2012 Dollars)

5.10 Group 10: Stock markets

-

1.

S&P’s Common Stock Price Index: Composite

-

2.

S&P’s Common Stock Price Index: Industrials

-

3.

S&P’s Composite Common Stock: Dividend Yield

-

4.

S&P’s Composite Common Stock: Price-Earnings Ratio

5.11 Group 11: Non-household balance sheets

-

1.

Federal Debt: Total Public Debt as Percent of GDP (Percent)

-

2.

Real Federal Debt: Total Public Debt (Millions of 2012 Dollars)

-

3.

Real Nonfinancial Corporate Business Sector Liabilities (Billions of 2012 Dollars)

-

4.

Nonfinancial Corporate Business Sector Liabilities to Disposable Business Income (Percent)

-

5.

Real Nonfinancial Corporate Business Sector Assets (Billions of 2012 Dollars)

-

6.

Real Nonfinancial Noncorporate Business Sector Liabilities (Billions of 2012 Dollars)

-

7.

Real Nonfinancial Noncorporate Business Sector Assets (Billions of 2012 Dollars)

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Alam, M. Output, employment, and price effects of U.S. narrative tax changes: a factor-augmented vector autoregression approach. Empir Econ (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-024-02591-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-024-02591-2