Abstract

This paper investigates the impact of macroprudential policy announcements on financial stability in Europe. Our three financial (in)stability proxies are systemic risk measures that cover all types of financial institutions and consider various financial market segments. We find that the announcements of macroprudential policy actions only contain banking systemic risk with the latter computed based on market data. However, when measuring systemic risk by including both market and balance sheet data, we observe an increase in the systemic risk of all financial institutions, banks and non-banks. This last result is confirmed when considering non-diversifiable risk across financial market segments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Notes

These intermediate objectives are: (i) mitigate and prevent excessive credit growth and leverage; (ii) mitigate and prevent excessive maturity mismatch and market illiquidity; (iii) limit direct and indirect exposure concentrations; (iv) limit the systemic impact of misaligned incentives with a view to reducing moral hazard; and (v) strengthen the resilience of financial infrastructures.

The LRMES, as defined by Brownlees and Engle (2017), is the expected value of firm returns conditional on the market being in distress over a 6-month period. At the country level, it gives the expected drop in return for all financial institutions in that country, in case of a severe prolonged crisis at a global level.

The SRISK measures the capital shortfall that a financial institution would experience in case of a severe financial crisis. It thus captures the contribution of each financial intermediary to the systemic risk of the financial system. At the country level, the SRISK is the sum of the SRISK of all financial institutions in a specific country.

We decide to use three different systemic risk measures in order to capture different dimensions of systemic risk. However, we acknowledge that there is no perfect measure of systemic risk, but finding such a measure is beyond the scope of the present paper.

This was precisely the starting point of the Basel Committee when they proposed the introduction of macroprudential rules.

These assumptions imply that if intermediary goals are met or if banking stability is reached, than the ultimate goal would also be achieved.

This adverse effect has already been proven for individual macroprudential measures and for intermediate goals (mainly credit growth). Meuleman and Vander Vennet (2020) show that the adverse effect of individual measures is not dominant in the total effect of the macroprudential framework on European banking systemic risk, but their study, conducted on bank level data, is based on the Marginal Expected Shortfall (MES, Acharya et al. (2017)) which could lead to ignoring the risks emanating from banks’ balance sheets.

For a comprehensive literature review on the effects of macroprudential policy, see Galati and Moessner (2018).

For example, a measure restricting access to credit for firms or households might determine them to substitute bank credit with the issuance of bonds or with cross-border sources of finance.

One example would be manipulating internal models to generate lower risk-weighted assets (González-Páramo 2012).

Furthermore, when regressing the macroprudential index on our systemic risk measures, we find that the policy actions are not the result of a change in systemic risk. This can be related to the fact that after the introduction of the macroprudential framework in Europe, national authorities were asked by the regulator to implement macroprudential measures (such as the (Other)-Systemically Important Institutions buffers or the Capital Conservation buffers) regardless of the build-up of systemic risk. The regression results are not reported in this paper, but can be provided upon request.

Including lagged variables in our model does not completely exclude the endogeneity bias. For example, a shock in \(t-1\) such as a sudden optimism about future house prices could lead to an increased demand for credit in the near future, that would trigger an increase in systemic risk at time t, but could also lead to an immediate response from the macroprudential authority. Our econometric specification does not take into account such a scenario, but given the monthly frequency of our data, we consider that situations where the response of the prudential authority is immediate (same month) are rather unlikely given that the design and implementation of a macroprudential action take time for authorities to set up.

Table 3 in Appendix A provides the correlation matrix for the independent variables. We can note that all correlations are inferior to 0.5 in absolute value. This suggests the absence of a multicollinearity problem.

A description of all variables is provided in Appendix A.

The approximation is given by the following formula: LRMES\(_{it}=1- exp(18*\textrm{MES}_{it})\).

Indeed, the LRMES depends strongly on systematic risk measured by the time-varying beta. Benoit et al. (2017) show that the MES can be also expressed as the product between the beta of a financial institution and the expected shortfall of the market.

Although considering balance sheet date, the SRISK does not account for the origin of the debt - domestic or foreign, financial or non-financial. One could argue that banks holding domestic debt financed by financial institutions should be more systemically important for the home country. However, SRIKS would not capture such subtleties.

The CLIFS is obtained by aggregating the information from three individual stress sub-indices. The aggregation takes into account time-varying correlations between the sub-indices and puts thus a higher weight on situations in which stress prevails in several market segments at the same time. The three sub-indices correspond to three financial market segments: equity markets, bond markets and foreign exchange markets and are computed from market data on realized volatilities and risk spreads.

The descriptive statistics of all three measures are presented in Appendix B.

The “other measure” category contains structural measures, other regulatory restrictions on financial activities and limits on deposit rates, among others.

For more details on the methodology used to compute the index, see Meuleman and Vander Vennet (2020).

For more information on the variables, see Table 2 in Appendix A.

Germany, Austria, Belgium, Spain, Finland, France, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Portugal and Greece.

This was particularly true before the enforcement of the bail-in procedure in Europe, in 2016, under the second pillar of the Single Resolution Mechanism.

Consider for example what happens when volatilities and correlations increase, leading to an increase in market risk VaR and capital requirements. Banks will, in this situation, all try to reduce their exposures and do similar trades in order to comply with prudential rules. However, this behavior might lead to liquidity evaporating or to asset fire sales.

We argue that LRMES and CLIFS will rather react to the announcement of such measures as they are built exclusively on market data.

We carried out robustness tests for the banking, non-banking and whole financial system. Results can be provided upon request.

References

Acharya V, Bergant K, Crosignani M, Eisert T, McCann F (2017) The anatomy of the transmission of macroprudential policies: evidence from Ireland. In: 16th international conference on credit risk evaluation, interest rates, growth, and regulation, pp. 28–29

Acharya V, Engle R, Richardson M (2012) Capital shortfall: a new approach to ranking and regulating systemic risks. Am Econ Rev 102(3):59–64

Acharya V, Pedersen LH, Philippon T, Richardson M (2017) Measuring systemic risk. Rev. Financ. Stud. 30(1):2–47

Aiyar S, Calomiris CW, Wieladek T (2014) Does macro-prudential regulation leak? Evidence from a UK policy experiment. J Money Credit Bank 46(s1):181–214

Akinci O, Olmstead-Rumsey J (2018) How effective are macroprudential policies? An empirical investigation. J Financ Intermed 33:33–57

Alam Z, Alter MA, Eiseman J, Gelos MR, Kang MH, Narita MM, Wang N (2019) Digging deeper–evidence on the effects of macroprudential policies from a new database. International Monetary Fund

Altunbas Y, Binici M, Gambacorta L (2018) Macroprudential policy and bank risk. J Int Money Financ 81:203–220

Benoit S, Colliard J-E, Hurlin C, Pérignon C (2017) Where the risks lie: a survey on systemic risk. Rev Finance 21(1):109–152

Bonfim D, Soares C (2018) The risk-taking channel of monetary policy: exploring all avenues. J Money Credit Bank 50(7):1507–1541

Brownlees C, Engle RF (2017) SRISK: a conditional capital shortfall measure of systemic risk. Rev Financ Stud 30(1):48–79

Budnik KB, Kleibl J (2018) Macroprudential regulation in the European Union in 1995-2014: introducing a new data set on policy actions of a macroprudential nature. ECB working paper

Caballero RJ, Hoshi T, Kashyap AK (2008) Zombie lending and depressed restructuring in Japan. Am Econ Rev 98(5):1943–77

Cerutti E, Claessens S, Laeven L (2017) The use and effectiveness of macroprudential policies: new evidence. J Financ Stab 28:203–224

Cizel J, Frost J, Houben A, Wierts P (2019) Effective macroprudential policy: crosssector substitution from price and quantity measures. J Money Credit Bank 51(5):1209–1235

Colletaz G, Levieuge G, Popescu A (2018) Monetary policy and long-run systemic risk-taking. J Econ Dyn Control 86:165–184

Drehmann M, Borio CE, Tsatsaronis K (2012) Characterising the financial cycle: don’t lose sight of the medium term! BIS working paper

Driscoll JC, Kraay AC (1998) Consistent covariance matrix estimation with spatially dependent panel data. Rev Econ Stat 80(4):549–560

Duprey T, Klaus B, Peltonen T (2017) Dating systemic financial stress episodes in the EU countries. J Financ Stab 32:30–56

Engle R, Jondeau E, Rockinger M (2015) Systemic risk in Europe. Rev Finance 19(1):145–190

Farhi E, Tirole J (2012) Collective moral hazard, maturity mismatch, and systemic bailouts. Am Econ Rev 102(1):60–93

Fendoğlu S (2017) Credit cycles and capital flows: effectiveness of the macroprudential policy framework in emerging market economies. J Bank Finance 79:110–128

Gaganis C, Lozano-Vivas A, Papadimitri P, Pasiouras F (2020) Macroprudential policies, corporate governance and bank risk: cross-country evidence. J Econ Behav Organ 169:126–142

Galati G, Moessner R (2018) What do we know about the effects of macroprudential policy? Economica 85(340):735–770

Garcia Revelo JD, Levieuge G (2022) When could macroprudential and monetary policies be in conflict? J Bank Finance 139:106484

Garcia Revelo JD, Lucotte Y, Pradines-Jobet F (2020) Macroprudential and monetary policies: the need to dance the tango in harmony. J Int Money Finance 108:102156

González-Páramo J (2012) Operationalising the selection and application of macroprudential instruments. Bank of International Settlements, Report (48)

Goodhart C (2008) The boundary problem in financial regulation. Natl Inst Econ Rev 206(1):48–55

Hollo D, Kremer M, Lo Duca M (2012) CISS-a composite indicator of systemic stress in the financial system. ECB working paper (1426)

Hull J (2012) Risk management and financial institutions. John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken, New Jersey

Jiménez G, Ongena S, Peydró J-L, Saurina J (2014) Hazardous times for monetary policy: what do twenty-three million bank loans say about the effects of monetary policy on credit risk-taking? Econometrica 82(2):463–505

Jiménez G, Ongena S, Peydró J-L, Saurina J (2017) Macroprudential policy, countercyclical bank capital buffers, and credit supply: evidence from the Spanish dynamic provisioning experiments. J Polit Econ 125(6):2126–2177

Kortela T (2016) A shadow rate model with time-varying lower bound of interest rates. Bank of Finland Research Discussion Paper (19)

Kuttner KN, Shim I (2016) Can non-interest rate policies stabilize housing markets? Evidence from a panel of 57 economies. J Financ Stab 26:31–44

Markose S, Giansante S, Shaghaghi AR (2012) “Too interconnected to fail’’ financial network of US CDS market: topological fragility and systemic risk. J Econ Behav Organ 83(3):627–646

Meuleman E, Vander Vennet R (2020) Macroprudential policy and bank systemic risk. J Financ Stab 47:100724

Neuenkirch M, Nöckel M (2018) The risk-taking channel of monetary policy transmission in the euro area. J Bank Finance 93:71–91

Rose AK, Spiegel MM (2011) Cross-country causes and consequences of the crisis: an update. Eur Econ Rev 55(3):309–324

Vandenbussche J, Vogel U, Detragiache E (2015) Macroprudential policies and housing prices: a new database and empirical evidence for Central, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe. J Money Credit Bank 47(S1):343–377

Vašíèek B, Žigraiová D, Hoeberichts M, Vermeulen R, Šmídková K, de Haan J (2017) Leading indicators of financial stress: new evidence. J Financ Stab 28:240–257

Wagner W (2010) Diversification at financial institutions and systemic crises. J Financ Intermed 19(3):373–386

Zhang L, Zoli E (2016) Leaning against the wind: macroprudential policy in Asia. J Asian Econ 42:33–52

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Robert Engle and Brian Reis for providing them with the data on LRMES and SRISK and Yannick Lucotte for the data on the shadow rate. We are grateful to Pierre Durand, Jose David Garcia Revelo, Etienne Lepers, Yannick Lucotte, Gonçalo Pina and Anne-Gaël Vaubourg for helpful discussions and comments. We are also thankful to participants in the 2021 AFSE Conference, the 2021 GdRE Annual Meeting, the 2021 ICMAIF and the 2021 PhD Student Conference in International Macroeconomics, as well as to participants in the CRIEF seminar at University of Poitiers for their remarks. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

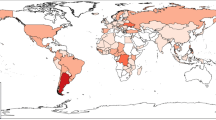

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

1.1 A. Description of variables

The quarterly series, namely credit and the nominal residential property price index, have been transformed into a monthly frequency following the linear interpolation techniques, after treating them for seasonal effects using the STL decomposition method (Seasonal and Trend decomposition using Loess).

We convert total credit and the SRISK measure from US dollar to Euro using the monthly average exchange rate (Tables 2, 3).

1.2 B. Descriptive statistics on financial stability indicators

See Table 4.

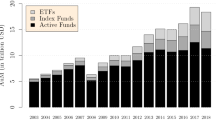

1.3 C. Macroprudential index evolution

See Fig. 1.

1.4 D. Robustness check results

1.4.1 D.1. Country samples

1.4.2 D.2. Sensitivity tests Footnote 27

1.4.3 D.3. Endogeneity bias

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Jbir, H., Oros, C. & Popescu, A. Macroprudential policy and financial system stability: an aggregate study. Empir Econ 66, 1941–1973 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-023-02524-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-023-02524-5