Abstract

This paper focuses on the spillover dynamics of shocks originating in China during the last two decades. More specifically, the paper compares the effects of a shock to China’s GDP and exchange rate using early 2000s trade patterns with those of two decades later. We use a global vector autoregressive (GVAR) model as it allows to consider trade interactions as well as financial linkages through interest rates, stock prices, and exchange rates. Our results indicate that the shock spillovers from China have become more pronounced over the past two decades. While the world has become more exposed to China’s economy, it has become more susceptible to Chinese economic shocks. This paper contributes to the literature by evaluating the dynamics of China’s spillover effects and highlights the structural changes in trade between major global trade players.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The world has seen the steady rise of China over the past four decades, a remarkable and undoubtedly unimaginable lifting hundreds of millions out of absolute poverty. China has transformed from a poor country to an upper-middle-income economy during the last two decades, and it is projected to become a high-income country by 2023, two years earlier than its own 14th plan (CEBR report 2021). It is well understood that trade has played a crucial role in China’s road to prosperity. The share of China in global trade has increased from less than 1% in the 1970s to about 15% to date and, since 2010, China has become a country with the largest share in total merchandise imports and exports worldwide (DOI Statistics).Footnote 1 The remarkable trend of China’s economic miracle has had a considerable impact on other economies’ growth. China’s trade shares with the USA, Europe, and the rest of the world (ROW) have changed significantly over the past two decades. China has tripled its trade with Europe and the ROW, as it has managed to double it with the USA (Table 1). As China becomes wealthier, with a large share of the world’s trade, an interesting question is how the role of China’s economy in the world has changed? More specifically, how have the spillovers of shocks that originated from the Chinese economy evolved over the years? We know any shocks in economies such as the USA or Europe have been always significant to the rest of the world. These large economies have played significant roles in being the dominant economic forces through various channels including trade, financial, and economic policies. With China gaining more economic power, how have these economies’ roles changed over the past two decades on the world stage? Are their economic spillovers as powerful as before? Or have they passed the baton to China? Has China’s business cycle (if any) become more important to the world?

While extended research is needed to answer these questions, this paper, narrowly, focuses on the role of China and tries to see how the Chinese economy has become more relevant to the world. We follow Dees et al. (2007a) and use a global vector autoregressive (GVAR) model to assess the economic spillovers of China’s shocks to the world, especially to the USA, Europe, and a set of other economically significant countries where we aggregate them in the ROW. Particularly, we assess the transmitting power of China’s shocks to the world economy given its trading pattern twenty years ago and compare it with the most current trading pattern. The results of this study could be useful for policymakers and international regulators in understanding the evolving role of the Chinese economy and its policies. We base our identification strategy on Chinese import shock literature (Autor et el. 2013), and assume that using the GVAR model, we can identify the spillovers of China-specific shocks (see Eickmeier and Ng (2015) and the key results section below).

The GVAR model provides a comprehensive and transparent framework to study the spillover effects of different shocks as it captures trade and financial interactions. In this model, we consider 41 countries, which consist of more than 80% of the world economy, grouped into two regions (i.e., Europe and the rest of the world), and two single economies, China and the USA. We investigate the effect of a slowdown in China as well as a currency devaluation shock, by first assuming a trade pattern in 2000–2002, and then, compare it with an analysis using the 2015–2017 trade pattern.Footnote 2 The analysis reveals how trade patterns and the structure of economies have changed the transmission of shocks between countries. We chose 2017 as the cutoff year for our trade data to exclude the recent trade tensions between the USA and China. While a fast-growing strand of the literature focuses on spillover effects of shocks using different methodologies, less attention has been paid to its dynamic over time. This study contributes to the literature by looking at the dynamics of China’s economic spillovers, in the context of an integrated model. Our results indicate that the spillovers of economic shocks originating from China have been increased in the last two decades due to the substantial increasing role of China’s trade and financial linkages in the world. This is not surprising, but an interesting finding, while the world has become more exposed to China’s economy through trade and financial channels, at the same time, it has become more susceptible to Chinese economic shocks.

The paper is structured as follows: we start with a brief description of the global and regional trade development in the last two decades, we then briefly review the related literature. The GVAR framework and the details of the data are presented later. Impulse responses of various shocks to China’s economy with a different choice of trade weights, and the conclusion of the paper come at the end.

2 Recent development in trade with China

While increasing integration can boost the economy and benefit countries through risk-sharing and consequently stability, it could make countries more vulnerable to external shocks. Empirical studies show that more integrated countries are more vulnerable to external shocks (Frankel and Rose 1998; Baxter and Kouparitsas 2005; Fidrmuc and Korhonen 2010). This has important implications for conducting fiscal, monetary, and exchange rate policies for policymakers as well as risk management for banks and corporations.

As noted by Autor et el. (2013), migration of labors to cities, access to transfers of technologies, and the sheer presence of multinational companies helped China to transform from an agrarian isolated economy to a vibrant industrial economic powerhouse. This market-oriented movement was strengthened by productivity growth in China (Hsieh and Ossa 2016). China’s remarkable expansion fueled by investment-driven growth has slowed down recently and the country rebalanced from import-intensive investment towards consumption (Blagrave and Vesperoni 2018).

Along with a strong trend in global integration, the trade structure and the major players have changed as well. Fast economic growth in emerging countries, especially in China, in the last three decades, along with sluggish growth in advanced economies has changed the global trade pattern. China as one of the world’s fastest growing economies in the last two decades has established itself as a crucial player in the global economy. While China’s share of global GDP was less than 2% in 1980, and 3.6% in 2000, it has recently surpassed 17%, making it the second largest country in terms of contribution to the world’s GDP after the USA with about 27%.Footnote 3 The IMF (2020) World Economic Outlook indicated that by 2025, the share of China in the world GDP would reach 20.3% while that of the USA would shrink to 22.7%. Furthermore, the UK-based Centre for Economics and Business Research predicted that China would become the largest economy in 2028. A similar pattern is evident in the role of China in international trade. Since 2010, China has become the country with the largest share in total imports and exports worldwide (DoTs Statistics). With the increasing role of China in global trade, any shocks in China would lead to more significant effects on other countries.

China’s economic expansion has brought key changes to the composition of major economies’ trading partners (Table 1). While in 2000–2002, trade with China accounted for only 8.8% of total US trade, it reached 20% in 2015–2017. The same trend happened with Europe, where its trade share with China increased from 12.9% in the early 2000s to almost 33% two decades later, a threefold increase in less than 20 years. A similar pattern has happened to the trade pattern of the ROW with China, 11% of China’s share in 2000–2002 has become almost threefold in 2015–2017. On the other hand, China has steadily maintained similar composition of its trading partners. For example, it traded 24.4% of its total imports and exports with the USA in 2000–2002, which has roughly stayed at the same order in 2015–2017, and its trade share with Europe has slightly increased from 28.1 to 31.7% while that of with ROW slightly decreased from 47.5% in the early 2000s to 43.5% recently.Footnote 4 Figures 3 and 4 in “Appendix A” provide more details about the trading patterns between China and other countries.

3 Literature review

As the global economy becomes more integrated, countries are more exposed to the spillover effects of external shocks. This is highlighted through global economic crises such as the Asian financial crisis, the Great Financial Crisis, and more recently, the 2020 coronavirus pandemic.

A country-specific shock could transmit to other countries through different channels including trade and financial linkages. A rise in consumption or investment in one country could increase imports from trading partners and could boost their GDP (demand side).Footnote 5 Empirical studies note that the tighter the interdependency between countries, the more synchronized the business cycles (Fidrmuc and Korhonen 2010; Baxter and Kouparitsas 2005; Frankel and Rose 1998).

A fast-growing strand of the literature is focused on the business cycle synchronization and spillovers in the last two decades. Different methodologies have been used to evaluate the spillover effects including simultaneous equations (Imbs 2004), static correlation analysis (Kose et al. 2003), dynamic correlation analysis (Croux et al. 2001; Fidrmuc and Korhonen 2010), the wavelet-based measure of co-movement (Raihan et al. 2005; Aguiar-Conraria et al. 2008; Soares 2011), cyclical and synchronization measures (Darvas and Szapáry 2008), dynamic factor models (Kose et al. 2012; Dovern and Roye 2014), factor models (Del Negro 2002; Gross et al. 2016), vector auto regressions (VARs) or Panel VARs modeled using Bayesian techniques (Sznajderska and Kapuściński 2020), and GVAR models (Dees et al. 2007a, b; Pesaran et al. 2004; Feldkircher and Huber 2016).

In this paper, we use the GVAR model as a practical and traceable framework to quantitatively analyze the spillovers of China’s shocks on the real GDP of other countries. The GVAR model has a flexible framework to include several countries with a relatively large number of domestic and foreign variables and to cover various potential transmission mechanisms. As a global model, with a trade matrix, which loops countries together, the GVAR captures direct and indirect effects as well as the second-round effects through the impact of shocks on trading partners. Moreover, the GVAR modeling framework has been effectively addressed the common factor interdependency and co-movement of business cycle across economics (Dees et al. 2007a).

The GVAR model has been used to evaluate different macroeconomic shocks (Dees et al. 2007a, b; Pesaran et al. 2004; Chudik and Fratzscher 2011; Backé et al. 2013), the impact of quantitative easing (Gurara and Ncube 2013), the effect of conventional and unconventional monetary policies (Böck et al. 2021), effectiveness of Covid-19 fiscal support (Chudik et al. 2021a, b), effects of the financial crisis (Sgherri and Galesi 2009), oil price shocks (Dees et al. 2007a; Cashin et al. 2014; Galesi and Lombardi 2013), house price shocks (Cesa-Bianchi 2013), credit supply shocks (Eickmeier and Ng 2015), stress testing of the financial sector (Castrén et al. 2010), the international aspects of systemic financial stress shocks (Dovern and Roye 2014), economic uncertainty (Pfarrhofer 2019), credit risk modeling (Pesaran et al. 2006), China’s GDP growth slowdown and a surge in global financial market volatility (Cashin et al. 2017), forecasting (Pesaran et al. 2009), and counterfactual analysis (Pesaran et al. 2007; Chudik et al. 2021a, b).Footnote 6

The other stream of the literature related to our paper is to evaluate the spillover effects of the Chinese economy. Several studies have analyzed the impact of China’s increasing role in the world on different regions and various sectors by employing different techniques. Arora and Vamvakidis (2011) by using a panel VAR and VECM model estimate the effect of a shock in China on 172 countries for the period of 1960–2007. Furceri et al. (2017) assess the effects of China’s growth shocks on the output of other countries using a static and dynamic model.

Some studies mainly focused on the regional effects of a shock to the Chinese economy. To name a few, Inoue et al. (2015) investigate the effect of China’s slowdown on the Asia–Pacific region using a GVAR model, Li and Xinyi (2018) assess the potential spillover effects of a shock in China on ASEAN countries using GVAR and the Oxford macro-econometric model, Aasaavari et al. (2020) study the opportunities and challenges of China’s rebalancing on Asia and Latin America and the Caribbean countries, Sznajderska and Kapuściński (2020) assess China’s widening of domestic imbalances on Southeast Asia and Oceania using the Global VAR model and the Bayesian VAR models, and Cesa-Bianchi et al. (2012) compare the dynamics of spillovers of China GDP shock with that of the USA to five large Latin American countries.

Some studies focused on other aspects of China’s shocks. To name a few, a slowdown of Chinese aggregate demand, a commodity price slump, financial market corrections, and a devaluation of the Chinese currency on inflation in Europe and the USA (Metelli and Natoli 2017), the rising Chinese import competition on US local labor market outcomes such as unemployment, labor force participation and wages (Autor et al. 2013), the spillover effects of China’s productivity growth (Hsieh and Ossa 2016), the financial spillovers from China to regional markets (Arslanalp et al. 2016), the real estate investment slowdown in China (Ahuja and Nabar 2012), a slowdown in Chinese investment spending (Ahuja and Myrvoda 2012), spillover effects of China's Industrial growth on the overall price changes of base metals (Wang and Wang 2019), and the implications of China’s slowdown for international trade and partner country exports (Blagrave and Vesperoni 2018).

Our study adds to the literature as it estimates how China’s economic influence (translated in shock spillovers) on other countries has changed over time. To the best of our knowledge, the closest studies to our paper are Cesa-Bianchi et al. (2012) where they investigate the dynamic transmission of China’s GDP shock to Latin America, and Inoue et al. (2015) in which they evaluate China's GDP shock spillovers on the Asia–Pacific region. They both find stronger spillover effects during the time.

4 Empirical model

In this paper, we use the GVAR model, introduced by Pesaran et al. (2004) and developed by Dees et al. (2007a). The GVAR model is a detailed global framework that has been used to take into account the interactions between countries and to investigate the relative importance of a diverse source of economic co-movement among countries. A standard GVAR model includes a number of vector autoregressive (VAR) models that are augmented by weakly exogenous foreign variables (VARX*)—constructed using trade weights and the global variables. We follow the literature and assume that except for the USA, the countries in our model are all small open economies and the foreign-specific and global variables are weakly exogenous.

In this paper, we constructed a GVAR dataset to include 42 countries and used the International Financial Statistics (IFS), the World Economic Outlook (WEO), and the Haver Analytics datasets to cover the periods between Q1-2000 and Q3-2019.Footnote 7 However, to make the model traceable, we chose China and the USA as individual countries and grouped the European countries in Europe and the rest of the countries in the ROW.Footnote 8 In our model, the vector of country-specific variables represented by \(x_{it}\)=(\(y_{it}\), πit, \(e_{it}\), \(q_{it}\),\(r_{it}\)) includes real GDP (\(y_{it}\)), inflation (πit), real exchange rate (\(e_{it}\)), real equity index (\(q_{it}\)), and nominal interest rates (\(r_{it}\)). We used seasonally adjusted quarterly GDP in real term as real output; the first difference of the consumer price index (2010 = 100) as the rate of inflation; the exchange rate of domestic currency per unit of US dollar as the exchange rate, the Market Share Capital International (MSCI) as the equity index, and the policy rate or the 3-month treasury bill rate as the interest rate. We also used quarterly Brent crude oil prices as the global variable in the model. The detailed information about these variables is described in Appendix A. The following transformations are used for the variables in the model.

Similarly, the country-specific foreign variables \({x}_{it}^{*}\)=(\({y}_{it}^{*}\),\({\uppi }_{it}^{*}\),\({e}_{it}^{*}\),\({q}_{it}^{*}\),\({r}_{it}^{*}\)) were constructed by trade weights, such that \({x}_{it}^{*}=\sum_{J=0}^{N}{w}_{ij}{x}_{jt}\), where \({w}_{ij}\) are trade weights as in Table 1.Footnote 9 We used the annual Direction of Trade Statistics (DoTs) from 2000–2017 to construct the trade weights for all 42 countries in the sample. The trade weights were then used to construct foreign variables and to solve the GVAR model. All foreign variables and log of oil price (\({\mathrm{Poil}}_{it}^{*})\) were assumed to be weakly exogenous for all countries/regions except to the USA, as suggested by the literature. For the USA, due to its important role in the global financial market, the foreign equity index and the real interest rate of other countries were not included as foreign variables, and the oil price was considered as an endogenous variable. Table 2 shows a list of all domestic and foreign variables in the country-specific model. We followed Dees et al. (2007a) and estimated the GVAR model in two stages: Once the VARX* models are estimated, we used the estimated models to solve the GVAR model using the trade weight matrix.

Table 1 shows the trade weight matrix used for the model. Each column shows the sum of exports and imports of each country/region to the total sum of exports and imports of that particular country/region. We used trade weights in panels A and B of Table 1 to estimate two sets of GVAR models. This helped us analyze how China’s role in the world economy has changed, given its changed trade structure with key partners.Footnote 10

After we specified the variables for each country/region, then we examined the integration properties of domestic, foreign, and global variables of the model. The unit root test results for all variables at level, first difference, and the second difference are presented in Tables 7, 8, 9 of “Appendix B”, using both the Augmented Dicky Fuller (ADF) and Weighted Symmetric (WS) ADF tests as in Park and Fuller (1995). The number of lags for both tests was chosen by using the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC). The results indicate that most domestic and foreign variables are non-stationary at levels except for inflation. More specifically, real GDP, real equity indices, and real exchange rates are all I(1) except for China’s real GDP which is I(2). In addition, the majority of country-specific foreign variables are also I(1) except for inflation.

The individual models were estimated from Q1-2000 to Q3-2019. The lag structure was selected by the AIC. In line with other papers in this field, a specification of VARX*(2,1) for most countries/regions was satisfactory. We then tested each VARX* model to identify the cointegration relationships and estimated the corresponding error correction VARX* models. Table 3 summarizes the diagnostic test results which indicate between 2 and 4 cointegration relations for all countries/regions.

The weak exogeneity is the key assumption in GVAR models as it allows the country models to be estimated individually and then to be solved together. Once the VARX* models were estimated, we followed Johansen (1992) to test trade-weighted foreign and the global variables for weak exogeneity. We cannot reject the weak exogeneity of foreign and global variables for all models except for some variables for the USA. Table 3 presents the results.

The results of the serial correlation test of the VECMX* residuals are presented in Table 4 and confirm no serial correlation between residuals in the majority of equations.

One of the main problems in econometrics is the possibility of structural break, particularly in the large sample size (di Mauro and Smith 2013). Following Dees et al. (2007a), the structural stability of the estimated coefficients and error variances of the country-specific VEXMX* was assessed by several tests which are represented in Table 9 “Appendix B”.

An advantage of the GVAR model is that it allows us to test the contemporaneous effect between domestic and foreign variables which can be interpreted as impact elasticities.Footnote 11 The impact elasticity can be interpreted as an indicator of the international linkage between domestic and foreign variables, the higher the elasticity, the higher the co-movement between the two variables (Smith and Galesi, 2014). These estimated elasticities are presented in Table 5. Almost all impact elasticities are significant and have expected positive signs. For instance, a one percent increase in foreign GDP will increase China’s GDP by 0.3% in the same quarter. Large elasticities between domestic and foreign equity prices (around 1 in almost all cases) indicate the strong co-movements between the stock markets. Some equity price coefficients are slightly above unity which indicate moderate overreaction to the foreign stock price changes. As expected, this indicates that contemporaneous financial linkages are strong and have become stronger over time. The results also show that the elasticity of foreign inflation is low, except for the USA, where foreign inflation elasticity is much larger, but the impact has reduced over time. The insignificant and weak contemporaneous linkages between interest rates indicate low co-movement in monetary policy reactions.

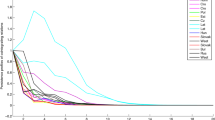

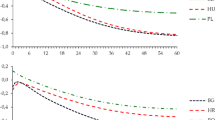

5 Key estimation results

The main advantage of the Global VAR model is that it allows us to evaluate the dynamic spillovers of various shocks originating in specific countries and regions. According to Eickmeier and Ng (2015), the exogeneity assumption in the GAVR model (see Table 3) allows us to identify spillovers across countries without identifying the structural shocks. To focus more on the main purpose of this paper, we only report the generalized impulse response functions (GIRFs) of a shock to the real GDP and the exchange rate of China, using the trade weight matrices of 2000–2002 and 2015–2017. The GIRFs indicate the dynamics of the transmission of these shocks to different economies. Figures 1 and 2 present a summary of bootstrap estimates of the GIRFs and their associated 90% confidence bounds of a shock to China’s real GDP and China’s real exchange rate in 2000–2002 and 2015–2017. These figures show that GIRFs quickly settle down in both models, indicating the stability of the models. The stability of the models is also supported by the eigenvalues and persistent profiles.Footnote 12 According to Dees et al. (2007a), the rank of the cointegration matrix in the global model should not exceed the total number of cointegration relations in all individual models. Our models satisfied these conditions.Footnote 13

Figure 1 reports the GIRFs of a one negative standard deviation shock to China’s real GDP. Note that the one standard deviation of China’s real GDP is quite small (equivalent to a fall of around 0.4% fall in GDP per quarter), which resulted in small reactions in the model. A fall in China’s GDP has a negative effect in all countries and they are statistically significant, except for Europe in the 2000–2002 model. The results suggest that China’s GDP shock would create larger spillovers and more volatility to other countries and regions recently, compared to the early 2000s. In other words, China’s shocks spillover more easily, as the global trade has become stronger. This is not surprising, but an interesting finding, while the world has become more exposed to China’s economy, through trade, at the same time, the world has become more vulnerable to Chinese economic shocks. The volatility of Chinese shocks on other parts of the world has increased compared to two decades ago, the giant production machinery in China, now, consumes a lot more of the world’s raw material and in turn, it produces a larger share of all goods manufactured in the world. The model shows that the bulk of the impact is in the first two years and in fact, the magnitude of responses in later years is almost as twice as early as 2000 (Fig. 1). This could be related to the more connected Chinese economy to the rest of the world through trade (reflected in our trade matrices as in Table 1) and the changes in the economies throughout the globe (reflected in different model specifications in our analysis). Our model results show that China is gaining a strong role in the world economy, its economy is becoming more relevant to the rest of the globe. For policymakers, this means that as China becomes more integrated with the rest of the world's economy, its economic policy would have stronger effect on affect other economies, particularly through trade and financial channels. The model shows that over time, China’s trade pattern has changed and along that, its spillover to the rest of the world has changed. China’s GDP shock has become more echoed in recent years compared to the early 2000s.

Figure 2 shows the GIRFs of an appreciation of Chinese currency on countries/regions GDP in the model. The GIRFs have the right signs, an appreciation of the yuan dampens real GDP levels. While the effect of the shock on the yuan was not statistically significant on the real GDP of the USA, Europe, and the rest of the world in the 2000–2002 model, this clearly has changed in the outer years, reflecting China’s ever-enhancing role in the global economy. It is worth mentioning that the GIRFs capture the direct and indirect impacts of the shock. Specifically, it not only captures the first-round impacts of, for instance, an appreciation of the yuan, but it also shows the second-round impacts of lower GDP of other countries in the model. This feature of the GVAR model helps to understand the global impact of a shock, which in the case of our example, shows how the currency movement in China impacts the global economy. Not surprisingly, the impacts of shocks have recently become more pronounced compared to the last two decades, again, confirming the ever-increasing role of the Chinese economy in the world. However, it is important to note that given a relatively stable Chinese exchange rate over the past decade or so, it is not that obvious whether shocks to China’s real exchange rate could have a significant impact on real GDPs. In any event, the origin of a shock to the real exchange rate could be a change in monetary policy, namely inflation or interest rate, or changes in the nominal exchange rate which would have come from changes in the relative prices, but since our model explicitly captures the impact of changes in inflation and interest rate, we could say that these changes are mostly due to changes in China’s real exchange rates (which of course, have been stable over the years). As the yuan has become one of the reserve currencies, the prominence of China’s exchange rate movements would become even more important in the coming years. Although the US dollar remains the dominant currency for trade and other financial transactions, China’s exchange rate policy has certainly gained more traction in trading partners’ economic policymaking. However, it should be noted that the yuan is not widely circulated outside China yet, basically shielding it from most transactions globally. This, of course, could change over time if China decides to become a financially more open economy.

6 Conclusion

The remarkable trend of China’s economic growth has had considerable impacts on other economies’ growth as well as spillovers of various shocks. In the meantime, China’s economic expansion has brought key changes to the composition of major economies’ trading partners. China’s trade shares with the USA, Europe, and the rest of the world have changed significantly over the past two decades. China has tripled its trade with Europe and the rest of the world, as it has managed to double it with the USA. As China becomes wealthier, with a large share of the world’s trade, an interesting question is how the role of China’s economy in the world has changed and how the spillover of the Chinese economy has evolved over the years. This question received more attention due to recent statistics that indicate that China has already surpassed the USA as the world’s largest economy based on purchasing power parity and with the projection of being the largest economy in the world GDP in 2028. According to the latest International Comparison Program report, the share of the world GDP based on purchasing power parities of the reference year of 2017, China has leapfrogged the USA as the world’s largest economy based on purchasing power parity of the reference year of 2017 (WEO, 2020).

This paper by using a GVAR model assessed the transmitting power of China’s shocks to the world economy given its trading pattern twenty years ago and compared it with the most current trading shares. The model used in this paper includes 41 countries, which consists of more than 80% of the world economy, grouped into two regions, Europe, and the rest of the world, and two single economies, China and the USA. We investigated the effect of a slowdown in China as well as a currency devaluation shock, by first assuming a trade pattern of 2000–2002 and compared it with an analysis using the 2015–2017 trade pattern. Our results indicate while the spillovers of China were small and, in some cases, statistically insignificant on the global economy in the past, they have increased in the last two decades due to the substantial increasing role of China’s global trade expansion in the world driven by the remarkable growth rate in investment and activities in China. This is not surprising, but an interesting finding, while the world has become more exposed to China’s economy, through trade, it has become more susceptible to Chinese economic shocks. For policymakers, China is not an isolated economy anymore, our simulated results show that its economy is becoming more integrated with the rest of the world, its macroeconomic policies are becoming more relevant to other countries, and these are already on the path to become more pronounced. As the Chinese economy becomes more open, especially to the financial world, the spillovers of China’s economy are expected to spread faster and stronger to the rest of the world.

Notes

The share of China’s imports in total world imports has increased from 6.2% in 2000 to 14.5% in 2020 (more than two times) while the share of China’s exports in world exports has increased from 3.6% to 10.3% in 2020 (almost three folds); In 2000, China was 7th largest exporter country, but since 2009 to date, China has been the world’s second-largest exporter after the US. A similar trend has happened in China’s imports as it was the 4th largest importer country in 2000, but it has been the largest importer country in the world since 2005 (DOI statistics).

Once we change the trade pattern, the specification of the GVAR model should also change, we have followed this approach in our analysis.

In 1980, it ranked 12th in terms of the largest share in the world GDP and ranked 6th in 2000. See https://www.theglobaleconomy.com/rankings/gdp_share/

These two-trade weight matrices were used in our model as a scheme for identifying the changes in the trade pattern between China and other countries during the last two decades.

Specialization due to trade might lead to a reduction in co-movement between countries’ business cycles (see Kose et al. 2003).

See Chudik and Pesaran (2016) for a survey of GVAR modeling. Cuaresma et al. (2016) address some advancements in the GVAR modeling including identification of shocks (Eickmeier and Ng 2015), specification of international linkages (Chudik and Fratzscher 2011, Eickmeier and Ng 2015, Feldkircher and Huber 2016, Galesi and Sgherri 2013), including the financial matrix alongside the trade matrix (Sgherri and Galesi 2009, Backé et al. 2013), estimating weight matrices (Gross 2019), and forecasting techniques (Cuaresma et al. 2016).

We use GVAR Toolbox 2.0 to estimate the model, available at https://sites.google.com/site/gvarmodelling/gvar-toolbox.

The database includes the US, China, Europe, and ROW. All European countries are grouped in the Europe region which includes Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Switzerland, Cyprus, Czech, Germany, Denmark, Spain, Estonia, Finland, France, Great Britain, Greece, Croatia, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Lithuania, Luxemburg, Latvia, Malta, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Russia, Slovakia, Slovenia, Sweden, and Turkey. Australia, Brazil, Canada, India, Indonesia, Japan, Korea, and Mexico determine the rest of the world region (ROW).

The ratio of export plus import over GDP.

It is estimated coefficients of domestic variables on the contemporaneous foreign specific variable.

All eigenvalues are equal or less than unity.

The total number of cointegration relations is 11 (in 2000–02) and 10 (in 2015–17). Therefore, the GVAR model should have at least 7 eigenvalues (i.e., 18–11) in our specification in 2000–02 and at least 10 eigenvalues (i.e., 20–10) in our 2015–17 specification that fall on the unit circle. Both specifications satisfy the condition. In the 2000–02 model, 7 eigenvalues equal to unity and the remaining 33 eigenvalues having moduli all less than one, these numbers are equal to 10 and 29 in our 2015–17 specification.

Variable Name: National Accounts, Expenditure, Gross Domestic Product, Real, Spliced Historical Series, Seasonally Adjusted, Index, (2010 = 100).

Variable name: Prices, Consumer Price Index, All items, Index, 2010 = = 100.

Variable name: Exchange Rates, National Currency Per U.S. Dollar, Period Average, Rate.

Variable name: MSCI Share Price Index excluding dividend, USD.

Variable Name: Monetary and Financial Accounts, Interest Rates, Other Depository Corporations Rates, Interbank Rates, Money Market Rate, Percent per Annum.

Variable Name: Monetary and Financial Accounts, Interest Rates, Central Bank Policy Rates, Discount Rate, Percent per Annum.

Variable Name: Monetary and Financial Accounts, Interest Rates, Securities Markets, Government Debt Securities, Treasury Bills, Percent per Annum.

Variable Name: Malta 3-Month Treasury Bill Yield (AVG, %), Switzerland 3-Month Treasury Bill Rate (EOP, %).

References

Aasaavari N, Di Vittorio F, Lariau A, Li Y, Mano RC, Rodriguez PC, Srinivasan K (2020) China's rebalancing: opportunities and challenges for LAC exporters. IMF Working Papers vol. 20(239)

Aguiar-Conraria L, Azevedo N, Soares MJ (2008) Using wavelets to decompose the time–frequency effects of monetary policy. Physica A 387(12):2863–2878

Ahuja MA, Myrvoda MA (2012) The spillover effects of a downturn in China’s real estate investment. International Monetary Fund. No. 12–266

Ahuja MA, Nabar MM (2012) Investment-led growth in China: Global spillovers. International Monetary Fund. No. 12–267

Arora V, Vamvakidis A (2011) China’s economic growth: international spillovers. Chin World Econ 19(5):31–46

Arslanalp MS, Liao W, Piao S, Seneviratne M (2016) China’s growing influence on Asian financial markets. International Monetary Fund. No. 16–173

Autor HD, Dorn D, Hanson GH (2013) The China syndrome: local labor market effects of import competition in the United States. Am Econ Rev 103(6):2121–2168

Backé P, Feldkircher M, Slačík T (2013) Economic spillovers from the euro area to the CESEE region via the financial channel: a GVAR approach. Focus on Eur Econ Integr 4:50–64

Baxter M, Kouparitsas MA (2005) Determinants of business cycle comovement: a robust analysis. J Monet Econ 52(1):113–157

Blagrave P, Vesperoni E (2018) The implications of China’s slowdown for international trade. J Asian Econ 56:36–47

Böck M, Feldkircher M, Siklos PL (2021) International effects of euro area forward guidance. Oxford Bull Econ Stat 83(5):1066–1110

Böck M, Feldkircher M, Huber F (2020) BGVAR: Bayesian global vector autoregressions with shrinkage priors in R. Globalization and Monetary Policy Institute Working Paper, N. 395

Cashin P, Mohaddes K, Raissi M (2014) The differential effects of oil demand and supply shocks on the global economy. Energy Econ 44:113–134

Cashin P, Mohaddes K, Raissi M (2017) China’s slowdown and global financial market volatility: is world growth losing out? Emerg Mark Rev 31:164–175

Castrén O, Dées S, Zaher F (2010) Stress-testing euro area corporate default probabilities using a global macroeconomic model. J Financ Stab 6(2):64–78

Centre for Economics and Business Research (2021) World economic league table 2021, a world economic league table with forecasts for 193 countries to 2035, 12th edition. Available at https://cebr.com/service/macroeconomic-forecasting/

Cesa-Bianchi A (2013) Housing cycles and macroeconomic fluctuations: a global perspective. J Int Money Financ 37:215–238

Cesa-Bianchi A, Pesaran MH, Rebucci A, Xu T, Chang R (2012) China’s emergence in the world economy and business cycles in latin America [with comment]. Economía 12(2):1–75

Chudik A, Fratzscher M (2011) Identifying the global transmission of the 2007–2009 financial crisis in a GVAR model. Eur Econ Rev 55(3):325–339

Chudik A, Pesaran MH (2016) Theory and practice of GVAR modelling. J Econ Surv 30(1):165–197

Chudik A, Mohaddes K, Raissi M (2021a) Covid-19 fiscal support and its effectiveness. Econ Lett 205:109939

Chudik A, Mohaddes K, Pesaran MH, Raissi M, Rebucci A (2021b) A counterfactual economic analysis of Covid-19 using a threshold augmented multi-country model. J Int Money Financ 119:102477

Croux C, Forni M, Reichlin L (2001) A measure of comovement for economic variables: theory and empirics. Rev Econ Stat 83(2):232–241

Cuaresma JC, Feldkircher M, Huber F (2016) Forecasting with global vector autoregressive models: a Bayesian approach. J Appl Economet 31(7):1371–1391

Darvas Z, Szapáry G (2008) Business cycle synchronization in the enlarged EU. Open Econ Rev 19(1):1–19

Dees S, Holly S, Pesaran MH, Smith LV (2007a) Long run macroeconomic relations in the global economy. Econ Open-Access Open-Assess E-J 1(1):1–29

Dees S, di Mauro F, Pesaran MH, Smith LV (2007b) Exploring the international linkages of the Euro area: a Global VAR analysis. J Appl Economet 22(1):1–38

Del Negro M (2002) Asymmetric shocks among US states. J Int Econ 56(2):273–297

di Mauro, F., & Smith, L. V. (2013) The basic GVAR DdPS model. The GVAR Handbook: Structure and Applications of a Macro Model of the Global Economy for Policy Analysis, 12

Dovern J, van Roye B (2014) International transmission and business-cycle effects of financial stress. J Financ Stab 13:1–17

Eickmeier S, Ng T (2015) How do US credit supply shocks propagate internationally? A GVAR approach. Eur Econ Rev 74:128–145

Feldkircher M, Huber F (2016) The international transmission of US shocks—evidence from Bayesian global vector autoregressions. Eur Econ Rev 81:167–188

Fidrmuc J, Korhonen I (2010) The impact of the global financial crisis on business cycles in Asian emerging economies. J Asian Econ 21(3):293–303

Frankel JA, Rose AK (1998) The endogeneity of the optimum currency area criteria. Econ J 108(449):1009–1025

Furceri D, Jalles JT, Zdzienicka A (2017) China Spillovers: New evidence from time-varying estimates. Open Econ Rev 28(3):413–429

Galesi A, Lombardi MJ (2013) External shocks and international inflation linkages. The GVAR Handbook: Structure and Applications of a Macro Model of the Global Economy for Policy Analysis vol. 70

Galesi A, Sgherri S (2013) Regional financial spillovers across Europe. The GVAR Handbook: Structure and Applications of a Macro Model of the Global Economy for Policy Analysis pp. 255–270

Gross M (2019) Estimating GVAR weight matrices. Spat Econ Anal 14(2):219–240

Gross M, Kok C, Żochowski D (2016) The impact of bank capital on economic activity-Evidence from a mixed-cross-section GVAR model. ECB Working Paper No. 1888

Gurara DZ, Ncube M (2013) Global economic spillovers to Africa: A GVAR approach. Abidjan: African development bank. Working Paper Series No. 183

Hsieh CT, Ossa R (2016) A global view of productivity growth in China. J Int Econ 102:209–224

Imbs J (2004) Trade, finance, specialization, and synchronization. Rev Econ Stat 86(3):723–734

Inoue T, Kaya D, Ohshige H (2015) The impact of China’s slowdown on the Asia Pacific region: an application of the GVAR model. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper, No.7442

International Monetary Fund (2020) World Economic Outlook: A long and difficult ascent

Johansen S (1992) Determination of cointegration rank in the presence of a linear trend. Oxford Bull Econ Stat 54(3):383–397

Kose MA, Prasad ES, Terrones ME (2003) How does globalization affect the synchronization of business cycles? Am Econ Rev 93(2):57–62

Kose MA, Otrok C, Prasad E (2012) Global business cycles: convergence or decoupling? Int Econ Rev 53(2):511–538

Li W, Xinyi SL (2018) China’s increasing economic linkages with ASEAN and the potential spillover effects, ASEAN+ 3 macroeconomic research office staff working paper pp. 18–03

Metelli L, Natoli F (2017) The effect of a Chinese slowdown on inflation in the euro area and the United States. Econ Model 62:16–22

Park HJ, Fuller WA (1995) Alternative estimators and unit root tests for the autoregressive process. J Time Ser Anal 16(4):415–429

Pesaran MH, Schuermann T, Weiner SM (2004) Modeling regional interdependencies using a global error correcting macroeconometric model. J Bus Econ Statistics 22(2):129–162

Pesaran MH, Schuermann T, Treutler BJ, Weiner SM (2006) Macroeconomic dynamics and credit risk: a global perspective. J Money Credit Banking 38(5):1211–1261

Pesaran MH, Smith LV, Smith RP (2007) What if the UK or Sweden had joined the euro in 1999? An empirical evaluation using a global VAR. Int J Financ Econ 12(1):55–87

Pesaran MH, Schuermann T, Smith LV (2009) Forecasting economic and financial variables with global VARs. Int J Forecast 25(4):642–675

Pfarrhofer M (2019) Measuring international uncertainty using global vector autoregressions with drifting parameters. arXiv preprint . arXiv:1908.06325

Raihan SM, Wen Y, Zeng B (2005) Wavelet: a new tool for business cycle analysis. Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Working Paper Series No. 2005-050

Sgherri S, Galesi A (2009) Regional financial spillovers across Europe: a global VAR analysis. IMF Working Papers pp. 1–32

Smith LV, Galesi A (2014) GVAR Toolbox 2.0 User guide. Available at https://sites.google.com/site/gvarmodelling/gvar-toolbox

Soares MJ (2011) Business cycle synchronization and the Euro: a wavelet analysis. J Macroecon 33(3):477–489

Sznajderska A, Kapuściński M (2020) Macroeconomic spillover effects of the Chinese economy. Rev Int Econ 28(4):992–1019

Wang T, Wang C (2019) The spillover effects of China’s industrial growth on price changes of base metal. Resour Policy 61:375–384

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The authors thank three anonymous referees for their constructive comments and guidance throughout the review process. They also thank Vanessa Smith for her technical support. Razieh Zahedi participated in this research before she started working with the world bank. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the World Bank, its Executive Board, or the World Bank management.The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the IMF, its Executive Board, or IMF management

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendices

Appendix A: Data

This section shows the way that we construct variables for the model. Data were downloaded from the IFS, the WEO, and the Haver Analytics datasets and covered the periods between Q1-2000 and Q3-2019.

1.1 Gross domestic products

For the gross domestic product, we used seasonally adjusted real GDP (2010 = 100) available at the IFS database.Footnote 14 For Brazil, Indonesia, Russia, Slovak Republic, Turkey, and the UK, seasonally adjusted data were contained missing observations for some years; therefore, we transformed the quarterly real GDP index to the seasonally adjusted by using the Census Bureau’s X-12 program, available at http://www.census.gov/srd/www/x12a/. As the time series for India and China had many missing observations, we used seasonally adjusted real GDP from the Haver Analytics website.

1.2 Consumer price index

For the price index, we used the quarterly average consumer price index from the IFS data.Footnote 15

1.3 Exchange rate

Exchange rate variables are based on the exchange rate of domestic currency to one unit of USD and are downloaded from the IFS data set.Footnote 16 For some countries who were part of the EU since 2000, the exchange rate of Euro per USD is used. Data for exchange rates of Slovak Republic, Lithuania, Estonia, Cyprus, Greece, Latvia, Malta, and Slovenia, who have joined the EU after 2000, were downloaded from the Havor Analytics data set.

1.4 Equity price

Market Share Capital Index (MSCI) excluding dividend, downloaded from the Havor Analytics dataset, is used as a proxy for equity price.Footnote 17 Data for some countries including Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Lithuania, Latvia, Slovenia, and Romania were not available, and we did not consider their equity price in our model.

1.5 Short-term interest rate

Our preferred short-term interest rate for the model was the policy rate. However, quarterly data for policy rate were not available for all countries during the sample period; therefore, we replace it with other interest rates such as treasury bills when the policy rate for a country was not available. For developed countries such as Australia, Brazil, Bulgaria, Canada, Croatia Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Ireland, Korea, Latvia Mexico, Poland, Romania, Russia, Slovak Republic, Slovenia, and USA, money market interbank rates were used available from the IFS website.Footnote 18 For China, Hungry, India, and Turkey, central bank policy rates (discount rate) were used from the IFS website.Footnote 19 Government bonds or treasury bills, downloaded from the IFS, were used for Belgium, France, Greece, Italy, Japan, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Portugal, and Sweden.Footnote 20 For Malta and Switzerland, the 3-month treasury bill rate was used from the Havor Analytics dataset.Footnote 21 Finally, the overnight lending rate, downloaded from the central bank of Norway (Norges Bank), is used as a short-term interest rate for Norway .Footnote 22

Appendix B: Estimation Results

One of the main problems in econometrics is the possibility of structural break, particularly in the large sample size (di Mauro and Smith 2013). Following Dees et al. (2007a), the structural stability of the estimated coefficients and error variances of the country-specific VEXMX* are assessed by several tests which are represented in Table 9 including cumulative sum (CUSUM), and cumulative sum of squares (CUSUMSQ), parameter constancy against non-stationary alternatives test (\({\mathfrak{N}}\)), Wald form of the QLR statistic (QLR), the MW statistic (MV), and the APW statistic (APW). We also performed the heteroskedasticity-robust version of these tests.Footnote 23 The results vary across, while \({\mathfrak{N}}\), QLR, MV, and APW indicate that the null hypothesis of parameter stability (no structural break) cannot be rejected for all variables in all country-specific models, the CUSUM and CUSUMQ reject the parameter stability of domestic variables in Europe .

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zahedi, R., Shahmoradi, A. & Taiebnia, A. The ever-evolving trade pattern: a global VAR approach. Empir Econ 63, 1193–1218 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-021-02182-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-021-02182-5