Abstract

Urban poverty arises from the uneven distribution of poor populations across neighborhoods of a city. We study the trend and drivers of urban poverty across American cities over the last 40 years. To do so, we resort to a family of urban poverty indices that account for features of incidence, distribution, and segregation of poverty across census tracts. Compared to the universally-adopted concentrated poverty index, these measures have a solid normative background. We use tract-level data to assess the extent to which demographics, housing, education, employment, and income distribution affect levels and changes in urban poverty. A decomposition study allows to single out the effect of changes in the distribution of these variables across cities from changes in their correlation with urban poverty. We find that demographics and income distribution have a substantial role in explaining urban poverty patterns, whereas the same effects remarkably differ when using the concentrated poverty indices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Income segregation refers to the extent at which different income groups (poor, middle class, rich, for instance) are under- or over-represented in some neighborhoods compared to the city as whole. Measures of income segregation are conceptually different from concentrated poverty measures.

There are various criteria to establish whether two spatial units are close or not; among them, a main distinction can be made between the contiguity-based criteria (e.g., two spatial units are close if they share a common border) and the distance-based ones (e.g., two spatial units are close if the distance between their centroids is less than or equal to a chosen distance).

The relative weight of the difference in poverty incidence for the pair of tracts i and j in t, \(N_{i}^{{\mathcal {A}}_{t}}N_{j}^{{\mathcal {A}}_{t}}/\left( N^{{\mathcal {A}}_{t}}\right) ^{2}\), may differ from that in \(t+1\), \(N_{i}^{{\mathcal {A}}_{t+1}}N_{j}^{{\mathcal {A}}_{t+1}}/\left( N^{{\mathcal {A}}_{t+1}}\right) ^{2}\), for effect of changes in the relative distribution of population across census tracts.

The interpretation of D is consistent with the approach suggested by O’Neill and Van Kerm (2008) to examine income convergence across countries. O’Neill and Van Kerm (2008) broke down the change in the Gini index, obtaining a two-term decomposition where a component assesses to what extent the incomes of poorer countries, initially at the bottom of the distribution, have grown proportionally more than those of richer countries at the top of the initial distribution. Such a component is therefore considered as a measure of \(\beta \)-convergence in income across countries O’Neill and Van Kerm (2008).

The overall poverty incidence, P/N, changes also when all tract poverty incidences vary in the same proportion, while both D and R are equal to 0 in that case.

c being the relative variation in overall poverty incidence, C is equal to \(1/\left( 1+c\right) \) and ranges between 0 and \(+\infty \).

Both Census 1990 and 2000 and ACS determine a family poverty threshold by multiplying the base-year poverty thresholds (1982) by the average of the monthly inflation factors for the 12 months preceding the data collection. The poverty thresholds in 1982, by size of family and number of related children under 18 years can be found on the Census Bureau web-site: https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/income-poverty/historical-poverty-thresholds.html. For a four persons household with two underage children, the 1982 threshold is $9,783. Using the inflation factor of 2.35795 gives a poverty threshold for this family in 2013 of $23,067. If the disposable household income is below this threshold, then all four members of the household are recorded as poor in the census tract of residence, and included in the 2014 wave of ACS.

\(\beta \) here indicates the type of convergence and should not be confused with parameter \(\beta \) in Eq. 1.

For a detailed description of the variables used to construct our indicators, see Chetty et al. (2017) and Tables 6 and 10 at https://opportunityinsights.org/data/.

The unevenness dimension is captured by the dissimilarity index, measuring the proportion of poor individuals that should move to restore proportionality across the MSA tracts (about 30% on average across all MSAs), see Andreoli and Zoli (2014).

See Christafore and Leguizamon (2019) for alternative definitions of gentrification.

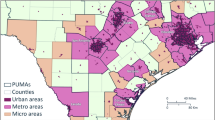

A spatial weights matrix representing the spatial relationships between census tracts in a MSA is needed to obtain the spatial decomposition. We specify a binary spatial weights matrix, the ij-th element of which equals 1 if tracts i and j are neighboring and 0 otherwise. A distance-based criterion is used to establish whether two tracts are neighboring Andreoli et al. (2021). More specifically, two tracts are considered close if the distance between their centroids is less than or equal to a cut-off distance, which is set equal to the minimum distance for which every tract in a MSA has at least one neighbor.

We do not report the fixed effects, which explains why the reported overall difference due to coefficients is not entirely explained by the variables shown in Table 9.

References

Alvarado SE, Cooperstock A (2021) Context in continuity: the enduring legacy of neighborhood disadvantage across generations. Res Soc Stratif Mobil 74:100620

Andreoli F, Mussini M, Prete V, Zoli C (2021) Urban poverty: measurement theory and evidence from American cities. J Econ Inequal (forthcoming)

Andreoli F, Peluso E (2018) So close yet so unequal: neighborhood inequality in American cities. ECINEQ Working paper p. 477

Andreoli F, Zoli C (2014) Measuring dissimilarity. Working Papers Series, Department of Economics, Univeristy of Verona, WP23

Ard K, Smiley K (2021) Examining the relationship between racialized poverty segregation and hazardous industrial facilities in the u.s. over time. Am Behav Sci 00027642211013417

Barro RJ, Sala-i-Martin X (1992) Convergence. J Polit Econ 100(2):223–251

Baum-Snow N, Marion J (2009) The effects of low income housing tax credit developments on neighborhoods. J Public Econ 93(5):654–666

Bischoff K, Reardon SF (2014) Residential segregation by income, 1970–2009. Divers Dispar Am Enters New Century 43

Blinder AS (1973) Wage discrimination: reduced form and structural estimates. J Hum Resour 8(4):436–455

Boardman JD, Finch BK, Ellison CG, Williams DR, Jackson JS (2001) Neighborhood disadvantage, stress, and drug use among adults. J Health Soc Behav 151–165

Chetty R, Friedman JN, Saez E, Turner N, Yagan D (2017) Mobility report cards: the role of colleges in intergenerational mobility. Working Paper 23618, National Bureau of Economic Research

Chetty R, Hendren N (2018) The impacts of neighborhoods on intergenerational mobility I: childhood exposure effects. Q J Econ 133(3):1107–1162

Chetty R, Hendren N, Katz LF (2016) The effects of exposure to better neighborhoods on children: new evidence from the moving to opportunity experiment. Am Econ Rev 106(4):855–902

Christafore D, Leguizamon S (2019) Neighbourhood inequality spillover effects of gentrification. Pap Reg Sci 98(3):1469–1484

Conley TG, Topa G (2002) Socio-economic distance and spatial patterns in unemployment. J Appl Econom 17(4):303–327

Dwyer RE (2012) Contained dispersal: the deconcentration of poverty in us metropolitan areas in the 1990s. City Commun 11(3):309–331

Huang Y, South S, Spring A, Crowder K (2021) Life-course exposure to neighborhood poverty and migration between poor and non-poor neighborhoods. Popul Res Policy Rev 40(3):401–429

Iceland J, Hernandez E (2017) Understanding trends in concentrated poverty: 1980–2014. Soc Sci Res 62:75–95

Jann B (2008) The Blinder-Oaxaca decomposition for linear regression models. Stata J 8(4):453–479

Jargowsky P (2015) The architecture of segregation. Century Found 7

Jargowsky PA (1997) Poverty and place: ghettos, barrios, and the American city. Russell Sage Foundation, New York

Jargowsky PA (2013) Concentration of poverty in the new millennium. Century Found Rutgers Cent Urban Res Educ

Jargowsky PA, Bane MJ (1991) Ghetto pverty in the United States, 1970–1980. In: Washington DC (ed) The urban underclass. The Brookings Institution, Washington, DC, pp 235–273

Jenkins SP, Brandolini A, Micklewright J, Nolan B (2013) The Great Recession and the distribution of household income. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK

Jenkins SP, Van Kerm P (2016) Assessing individual income growth. Economica 83(332):679–703

Kneebone E (2014) The growth and spread of concentrated poverty, 2000 to 2008–2012. Brook

Kneebone E, Nadeau C, Berube A (2011) The re-emergence of concentrated poverty. Brook Inst Metrop Oppor Ser

Lei M-K, Beach SR, Simons RL (2018) Biological embedding of neighborhood disadvantage and collective efficacy: influences on chronic illness via accelerated cardiometabolic age. Dev Psychopathol 30(5):1797–1815

Logan JR, Xu Z, Stults BJ (2014) Interpolating U.S. decennial census tract data from as early as 1970 to 2010: a longitudinal tract database. Prof Geogr 66(3):412–420 (PMID: 25140068)

Ludwig J, Duncan GJ, Gennetian LA, Katz LF, Kessler RC, Kling JR, Sanbonmatsu L (2012) Neighborhood effects on the long-term well-being of low-income adults. Science 337(6101):1505–1510

Ludwig J, Duncan GJ, Gennetian LA, Katz LF, Kessler RC, Kling JR, Sanbonmatsu L (2013) Long-term neighborhood effects on low-income families: evidence from moving to opportunity. Am Econ Rev 103(3):226–31

Ludwig J, Sanbonmatsu L, Gennetian L, Adam E, Duncan GJ, Katz LF, Kessler RC, Kling JR, Lindau ST, Whitaker RC, McDade TW (2011) Neighborhoods, obesity, and diabetes - a andomized social experiment. N Engl J Med 365(16):1509–1519 (PMID: 22010917)

Massey D, Denton NA (1993) American apartheid: segregation and the making of the underclass. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Massey DS, Gross AB, Eggers ML (1991) Segregation, the concentration of poverty, and the life chances of individuals. Soc Sci Res 20(4):397–420

Massey DS, Gross AB, Shibuya K (1994) Migration, segregation, and the geographic concentration of poverty. Am Sociol Rev 425–445

Nandi A, Glass TA, Cole SR, Chu H, Galea S, Celentano DD, Kirk GD, Vlahov D, Latimer WW, Mehta SH (2010) Neighborhood poverty and injection cessation in a sample of injection drug users. Am J Epidemiol 171(4):391–398

Oaxaca R (1973) Male-female wage differentials in urban labor markets. Int Econ Rev 14(3):693–709

O’Neill D, Van Kerm P (2008) An integrated framework for analysing income convergence. Manch Sch 76(1):1–20

Pearman F (2019) The effect of neighborhood poverty on math achievement: evidence from a value-added design. Educ Urban Soc 51(2):289–307

Quillian L (2012) Segregation and poverty concentration: the role of three segregations. Am Sociol Rev 77:354–379

Rey SJ, Smith RJ (2013) A spatial decomposition of the Gini coefficient. Lett Spat Resour Sci 6:55–70

Sampson RJ, Sharkey P, Raudenbush SW (2008) Durable effects of concentrated disadvantage on verbal ability among african-american children. Proc Natl Acad Sci 105(3):845–852

Sharkey P, Elwert F (2011) The legacy of disadvantage: multigenerational neighborhood effects on cognitive ability. Am J Sociol 116(6):1934–81

Smith JA, Zhao W, Wang X, Ratliff SM, Mukherjee B, Kardia SL, Liu Y, Roux AVD, Needham BL (2017) Neighborhood characteristics influence dna methylation of genes involved in stress response and inflammation: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Epigenetics 12(8):662–673

Thiede B, Kim H, Valasik M (2018) The spatial concentration of america’s rural poor population: a postrecession update. Rural Sociol 83(1):109–144

Thierry A (2020) Association between telomere length and neighborhood characteristics by race and region in us midlife and older adults. Health Place 62:102272

Thompson JP, Smeeding TM (2013) Inequality and poverty in the United States: the aftermath of the Great Recession. FEDS Working Paper No. 2013-51

Vinopal K, Morrissey TW (2020) Neighborhood disadvantage and children’s cognitive skill trajectories. Child Youth Serv Rev 116:105231

Wang Q, Phillips NE, Small ML, Sampson RJ (2018) Urban mobility and neighborhood isolation in america’s 50 largest cities. Proc Natl Acad Sci 115(30):7735–7740

Wilson W (1987) The truly disadvantaged: the inner city, the underclasses and public policy. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Wolf S, Magnuson KA, Kimbro RT (2017) Family poverty and neighborhood poverty: links with children’s school readiness before and after the great recession. Child Youth Serv Rev 79:368–384

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to two anonymous reviewers and to conference participants at RES 2018 meeting (Sussex), LAGV 2018 (Aix en Provence) and ECINEQ 2019 (Paris) for commenting on an earlier draft of the paper. The usual disclaimer applies. Replication code for this article is accessible from the authors’ web-pages. This work was supported by the Luxembourg Fonds National de la Recherche (IMCHILD grant INTER/NORFACE/16/11333934/IMCHILD and PREFER-ME CORE grant C17/SC/11715898) and by the University of Verona (Ricerca di Base grants MOBILIFE-2017-RBVR17KFHX and PREOPP-2019-RBVR19FSFA).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Andreoli, F., Mertens, A., Mussini, M. et al. Understanding trends and drivers of urban poverty in American cities. Empir Econ 63, 1663–1705 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-021-02174-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-021-02174-5

Keywords

- Concentrated poverty

- Gini index

- Oaxaca–Blinder decomposition

- Census

- American Community Survey

- Spatial inequality