Abstract

Import competition has been proxied by tariff protection in the extant literature on the impact of import competition on quality upgrading. This paper argues that allowing for non-tariff barriers as well as tariffs in measuring trade protection offers a more accurate measure of import competition. It investigates how the relationship between import competition and quality upgrading is affected by how import competition is measured by whether import competition is measured by overall protection rather than by tariff protection only. The import competition–quality upgrading relationship is shown to be sensitive to how import competition is measured, as well as the sample of countries and the measure of quality used in the empirical analysis. Tariff protection is found to be an inadequate measure for import competition for those products where non-tariff measures are also applied to protect against imports. Our study shows that import competition needs to be measured with care, especially in a world where tariffs are a relatively less important and non-tariff measures a relatively more important form of protection.

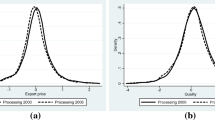

Source: Niu et al. (2018)

Similar content being viewed by others

Availability of data and materials (data transparency)

Available from the authors upon request.

Code availability (software application or custom code)

Available from the authors upon request.

Notes

The literature documents mixed findings of tariff reductions effect on productivity growth (see Baldwin and Yan 2012).

Information about the incidence of NTMs is available for fewer countries than is the case for tariffs, and prevents a comparison for the sample of countries used in Amiti and Khandelwal (2013). Indeed, it is the greater availability and accessibility of information on tariff than non-tariff protection that often encourages the adoption of tariffs by researchers to proxy protection by tariffs. Although the present study is for a smaller sample of countries, it includes only countries found in Amiti and Khandelwal (2013) and offers a similar mix of OECD and non-OECD countries (with around 35% of OECD and 65% of non-OECD countries in both studies.

For recent work on quality upgrading in a trade context, see Fieler et al. (2018).

See Amiti and Khandelwal (2013) for further details on the method and data used to estimate quality.

This covers price controls, quantity controls, monopolistic measures and technical measures.

Endogeneity potential of the incidence of NTMs is dealt with by instrumenting the core NTM incidence dummy by exports, change in imports, and the GDP-weighted average of the core NTMs for the five neighboring countries. This is modeled using a treatment effect regression à la Heckman, where a Probit model is run for each product using the instruments. Equation (3) is then fitted with the inverse Mills ratio estimated through this procedure.

This is the same approach to measuring protection levels at the variety level as used by Amiti and Khandelwal (2013). The number of times a given product level measure of protection is used depends therefore on the number of varieties in a product group and encourages the use of clustered standard errors for identifying the significance of estimated coefficients.

The AVEs of NTMs are estimated using the UNCTAD-MAST database (Niu et al. 2018). In the database, the data are available from 1997 and coverage for 2001 is much higher than 2000. Many developed countries, such as Australia, New Zealand and the European countries, have available NTM data since 2001. Therefore, to make the most of the data and to have a more balanced sample between developing and developed countries, we use the estimated AVEs of NTMs in 1997 and 2001 to substitute for the AVEs of NTMs in and 1995 and 2000, respectively. This means that lags on NTM protection are somewhat shorter than the 5-year lags adopted for tariff protection. We do check that our findings are not sensitive to these differences in lag structure for different types of trade policy.

The OECD countries in the sample are Australia, Canada, Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Netherlands, New Zealand, Portugal, Spain, Turkey and United Kingdom. While the non-OECD countries are Argentina, Brazil, Chile, China, Columbia, Costa Rica, Egypt, Guatemala, Hong Kong, Indonesia, India, Korea, Sri Lanka, Morocco, Mexico, Malaysia, Nicaragua, Peru, Philippines, Poland, Paraguay, Singapore, El Salvador, Thailand, Tunisia, Uruguay and Venezuela. All of these countries are included in the somewhat larger, but similar, sample of countries used by Amiti and Khandelwal (2013).

The high DB countries in the sample are Australia, Canada, Chile, Denmark, France, Germany, Hong Kong, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Korea, Malaysia, Nicaragua, Netherlands, New Zealand, Singapore, Spain, Thailand, Tunisia, Turkey and United Kingdom. The low DB countries in the sample are Argentina, Brazil, China, Columbia, Costa Rica, Egypt, Greece, Guatemala, Honduras, Indonesia, India, Sri Lanka, Morocco, Mexico, Peru, Philippines, Poland, Portugal, Paraguay, El Salvador, Uruguay, and Venezuela.

Note that, as in Amiti and Khandelwal (2013), the negative sign is only obtained if both country-year and product-year fixed effects are included in the empirical specification. This is the preferred specification, but the estimates for alternative configurations of the fixed effects are available from the authors.

The absence of significance on the tariff variable, which differs from Amiti and Khandelwal (2013), may be due to differences in the sample of countries between the studies, though as noted earlier there are not marked differences in the mix of country types between the studies. The decline in significance may also be due to the smaller sample size used in the present study. It should be noted that the point estimates of the coefficient on the tariff variable are similar in both studies.

We do check that our base findings are not sensitive to omitted variable bias. We introduce separately a number of variables that might affect quality upgrading and the relationship between import competition and quality upgrading, specifically tariffs in intermediate inputs, a revealed comparative advantage index and productivity shocks (proxied by change in total exports of a product to the world). These results are available from the authors on request. Critically, we do not find that the conclusions drawn about the quality upgrading-protection relations from Table 2 are sensitive to the introduction of these additional variables.

Of course, producers are able to observe the actual level of imports associated with the prevailing instruments of import protection in place, but they are not able to observe and would not find it easy to estimate the change in import competition that would be associated with the elimination of these instruments of protection.

References

Aghion P, Howitt P (1992) A model of growth through creative destruction. Econometrica 60(2):323–351

Aghion P, Bloom N, Blundell R, Griffith R, Howitt P (2005) Competition and innovation: an inverted-U relationship. Q J Econ 120(2):701–728

Aghion P, Burgess R, Redding S, Zilibotti F (2008) The unequal effects of liberalization: evidence from dismantling the license Raj in India. Am Econ Rev 98(4):1397–1412

Aghion P, Blundell R, Griffith R, Howitt P, Prantl S (2009) The effects of entry on incumbent innovation and productivity. Rev Econ Stat 91(1):20–32

Amiti M, Khandelwal AK (2013) Import competition and quality upgrading. Rev Econ Stat 95(2):476–490

Bacchetta M, Beverelli C (2012) Non-tariff measures and the WTO. VoxEU, posted July 31. https://voxeu.org/article/trade-barriers-beyond-tariffs-facts-and-challenges

Baldwin R (2016) The World Trade Organization and the future of multilateralism. J Econ Perspect 30(1):95–116

Baldwin J, Yan B (2012) Export market dynamics and plant-level productivity: impact of tariff reductions and exchange rate cycles. Scand J Econ 114(3):831–855

Bown CP (2014) Trade policy instruments over time. In: Martin LL (ed) The Oxford handbook of political economy of international trade. Oxford University Press, New York, pp 57–76

Bustos P (2011) Trade liberalization, exports, and technology upgrading: evidence on the impact of MERCOSUR on Argentinian firms. Am Econ Rev 101(1):304–340

Ding C, Niu Y (2019) Market size, competition, and firm productivity for manufacturing in China. Reg Sci Urban Econ 74:81–98

Fieler AC, Eslava M, Xu DY (2018) Trade, quality upgrading, and input linkages: theory and evidence from Colombia. Am Econ Rev 108(1):109–146

Kee HL, Nicita A, Olarreaga M (2009) Estimating trade restrictiveness indices. Econ J 119(534):172–199

Khandelwal A (2010) The long and short (of) quality ladders. Rev Econ Stud 77(4):1450–1476

Kugler M, Verhoogen E (2012) Prices, plant size, and product quality. Rev Econ Stud 79(1):307–339

Melitz M (2003) The impact of trade on aggregate industry productivity and intra-industry reallocations. Econometrica 71(6):1695–1725

Nicita A, Gourdon J (2013) A preliminary analysis on newly collected data on non-tariff measures policy issues. International trade and commodities study series, vol 53. UNCTAD, New York

Niu Z, Liu C, Gunessee S, Milner C (2018) Non-tariff and overall protection: evidence across countries and over time. Rev World Econ 154(4):675–703

Niu Z, Milner C, Gunessee S, Liu C (2020) Are nontariff measures and tariffs substitutes? Some panel data evidence. Rev Int Econ 28(2):408–428

Pavcnik N (2002) Trade liberalization, exit, and productivity improvements: evidence from Chilean plants. Rev Econ Stud 69(1):245–276

Segerstrom PS, Stepanok I (2018) Learning how to export. Scand J Econ 120(1):63–92

WTO (2012) Trade and public policies: a closer look at non-tariff measures in the 21st century. https://www.wto.org/english/res_e/publications_e/wtr12_e.htm

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Zhaohui Niu declares that she has no conflict of interest. Saileshsingh Gunessee declares that he has no conflict of interest. Chris Milner declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Niu, Z., Gunessee, S. & Milner, C. Import competition and quality upgrading revisited: the role of overall protection. Empir Econ 63, 1219–1246 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-021-02170-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-021-02170-9