Abstract

This study examines the effect of investor-level income taxes on profit repatriation and dividend payout policies of multinational firms. The empirical estimations include two million firm-year observations in 130 countries. By augmenting the Lintner model of dividend payments, I employ parametric as well as semiparametric techniques to provide evidence that income taxes on dividends neither alter dividend payments to investors nor within-firm dividend payments. These results remain robust to a wide range of alternative specifications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Should governments tax investor-level dividend income or not? During the last decades, this topic has received increased attention in the public debate and the literature. Since wealthy people have the means to invest in shares and therefore generate disproportionally large dividend incomes, it is often considered as fair to impose high taxes on dividends. However, taxing dividend income might distort the allocation of capital. Investors might find it less worthwhile to invest their savings in shares, or they could simply move their capital abroad. Furthermore, firms might decide to lower dividend payments to reduce the tax burden of their shareholders.

If firms adjust their dividend payments in response to tax changes, firms might also update how much profits they repatriate from the firms they possess. If firms aim at decreasing dividend payments, they might find it optimal to repatriate a lower share of these profits. Hence, higher investor-level taxes on capital might reduce the inflow of capital from abroad. Gaining more insights on this topic will increase our understanding of the potential cost governments face if they increase dividend income taxes. The investigation of these tax effects is the purpose of this paper.

The effect of changes in the dividend tax rate (DTR) on dividend payments (DIV) has already been discussed in the literature; the results suggest that dividend payments increase in response to lower tax rates (e.g., Poterba 2004; Chetty and Saez 2005). However, most studies are based on the US dividend income tax cut in 2003. This paper attempts to extend this approach by basing the econometric analysis on a large panel dataset including several reforms in different countries.

The conceptual framework is based on the Lintner model (Lintner 1956) which serves as the theoretical workhorse in the literature on dividend payments. The econometric analysis exploits balance sheet data from more than 1.3 million firms and a tax dataset which covers 165 countries. What makes this tax dataset unique is that it not only includes taxes on earned income for such a large number of countries, but also a wide range of other income taxes like the tax on dividend income. First, I replicate the Lintner model using different specifications. I find very similar results compared to previous studies. In a second step, for each firm, I include the tax rate of the country where the highest firm within the associated multinational firm (MNF) network resides. Henceforth, I will refer to this firm as the GUO (global ultimate owner). I do not only implement a standard parametric model for the econometric analysis, but I also allow for heterogeneous effects of the tax by means of a semiparametric approach. Furthermore, I present different robustness checks including alternative specifications and different subsamples.

The results indicate that investor-level dividend income tax rates do not play a significant role in the size of dividend payments, neither for dividend payments to investor-level shareholders nor for within MNF dividend payments. This suggests that the cost of increasing investor-level dividend income taxes is smaller than previous studies suggest.

This paper is structured as follows: I start with a review of the relevant literature in Sect. 2. The review is followed by a discussion of the conceptual framework and the empirical implementation in Sects. 3 and 4. Section 5 provides a description of the data and some first evidence of the tax effect. The results are presented in Sect. 6, which is followed by a discussion of the robustness checks in Sect. 7. Section 8 concludes.

2 Related literature

Among the earliest and most influential studies in the literature on the dividend policy of firms is the seminal work by Lintner (1956) who discusses the determinants of dividend payouts on the basis of survey evidence. However, while Lintner was concerned with the determinants of dividend payout, it was far from clear why firms pay dividends at all. In fact, following the Modigliani–Miller theorem (Modigliani and Miller 1958), in perfect capital markets, dividend payout policies of firms are not only irrelevant to the wealth of investors. Instead, retained earnings seem to be superior compared to dividend payments since capital gain taxes tend to be lower than dividend income taxes. Following Black (1976), this contradiction is often referred to as the Dividend Puzzle. This irrelevance finding was followed by a series of studies that aim at solving the Dividend Puzzle by providing rationals in favor of dividend payments. Shefrin and Statman (1984) argue that investors prefer a smooth and reliable dividend income stream over time compared to a large one-off payment at the moment when the stock is sold, due to unpredictable price fluctuations of the share. Similarly, Brennan (1971) assumes that dividend payments act as an insurance since firms may become insolvent before investors sell their share. A further rationale is provided by Ross (1977), Miller and Rock (1985), John and Williams (1985) and Ambarish et al. (1987), who ascribe dividend payments to the signaling of firms to inform investors of the conditions of the firm.

Many studies in this context rely on the Lintner model (Lintner 1956) which serves as the workhorse in the literature on dividend payouts. In short, it states that dividend payments depend positively on the desired payout ratio and former dividend payments. Hence, firms do not just set dividend payments according to the desired payout ratio but also aim at a smooth dividend payment stream over time. Lintner (1956) estimates a target–payout ratio of 50% and a speed of adjustment coefficient of 30%, Babiak and Fama (1968) obtain similar results. Desai et al. (2002) estimate the payout ratio to be larger for subsidiaries in high-tax countries. As dividends are, in a statistical sense, left censored (they cannot fall below zero), they base their estimations on the Tobit model. Desai et al. (2007) use the Lintner model to investigate how taxation, costly external finance and agency problems influence internal capital markets. Distinguishing between firms with and without a bond rating, Aivazian et al. (2006) find that the first exhibit a strong taste for dividend smoothing while the latter put more emphasis on a smooth dividend payment stream, i.e., adhering more to the payout ratio. Lehmann and Mody (2004) estimate the Lintner model in a within-MNF setting using the Arellano–Bond estimator.

Based on the Lintner model, Bellak and Leibrecht (2010) find a negative effect of taxes on dividend repatriations of German parent companies from foreign affiliates. Furthermore, the authors introduce a solution for the “initial conditions problem,” i.e., while dividend payments depend on past dividend payments, typically, the first payment is unobserved. Accounting for this problem leads to a larger estimated speed of adjustment coefficient. Also, they provide a detailed literature review on the Lintner model; a meta-regression analysis can be found in Fernau and Hirsch (2019). These results are in line with a wide range of qualitative studies, see Powell (2009) for a summary.

Having discussed the literature on how and why firms pay dividends, I now turn to the literature on dividend taxation.

One strand of this literature is concerned with the effect of investor-level income taxes on firm behavior. Chetty and Saez (2005) estimate a substantial increase in dividend payments in response to the US personal dividend income tax cut in 2003 (Jobs and Growth Tax Relief Reconciliation Act), Hanlon and Hoopes (2014) find that firms anticipated the dividend tax increases in 2011 and 2013 by shifting tax payments to the year prior to the tax increase (i.e., 2010 and 2012). Poterba (2004) finds similar results. However, using a difference-in-differences approach based on C- and S-corporations,Footnote 1 Yagan (2015) finds no effect of the 2003 tax cut on real investments of the firm. Following the argumentation of the author, this supports the so-called new-view hypothesis of dividend taxation which states that marginal investments are financed with retained earnings instead of newly issued equity. Alstadsæter et al. (2017) find similar results in response to changes in the Swedish dividend tax concerning the level of investment. However, they report changes in the allocation of investment.

A further strand is concerned with dividend repatriation taxes of US MNFs. Grubert (1998) provides a comprehensive analysis on how US dividend repatriation taxes affect royalty, dividend, interest and retained earnings of US multinationals’ foreign affiliates. Altshuler and Grubert (2003) discuss optimal strategies for the repatriation of profits from low-tax countries to the USA. Similarly, Desai et al. (2007) and Hanlon et al. (2015) explore the effect of US repatriation taxes on intra-firm dividend payments.

3 Dividend repatriation and income taxes

3.1 Dividends and taxes

As discussed in the literature review above, different studies find supportive evidence that firms adjust dividend payments in response to investor-level dividend income taxes in their own country. However, to the best of my knowledge, these studies do not take into account that MNFs might, in addition, adjust their intra-firm dividend payments in response to investor-level income tax changes. For illustrative reasons, consider the following example:

Individual-level investors buy shares of a firm A and participate in the profits of A through dividend payments (\(DIV_A\) in the figure). So far, previous studies examine to which extent investor-level dividend income tax rates in country HOME influence these dividend payments. However, in the context of MNFs, the profits of firm A do not only include the profits generated by firm A, but also the profits of B (the firm that is owned by A). Hence, if firm A indeed adjusts its dividend payments to its shareholders due to changes in investor-level income taxes, it might be reasonable for firm A to also adjust the repatriation of profits of the firms it owns (\(DIV_B\) in the figure). The goal of this paper is to examine if these dividend payments are responsive toward investor-level dividend taxes, i.e., if investor-level dividend income tax rates levied in country Home effect both dividend payments \(DIV_A\) and \(DIV_B\).

A further question that this paper is concerned with is if the effect of the tax (if there is any at all) is constant or if the effect changes with the size of the tax rate. For example, one could imagine a five percentage point increase in the tax rate to have a lower effect if it results in an overall tax rate of 25% instead of an overall tax rate of 60%. The econometric analysis allows for these heterogeneous effects of the tax rate by means of the semiparametric Baltagi-Li estimator.

In the following, I first introduce the Lintner model of dividend payouts and, in a next step, extend the model where I include the dividend tax rate, as well as further control variables. Subsequently, I discuss the econometric techniques that are applied.

3.2 The standard Lintner model of dividend payouts

As discussed above, the Lintner model (Lintner 1956) is commonly used in the literature to model dividend payments between firms and investors. This section provides a formal setup of the Lintner model and discusses how investor-level dividend income taxes may alter dividend payments.

The basic Lintner model proposes that dividend payments \(DIV_{it}\) of firm i in time t are the result of an adaptive process driven by the trade-off between the aim to generate a smooth dividend payment stream over time and the desired long-run dividend payment \(DIV^*_{it}=r\varPi _{it}\) with r being the desired long-run payout ratio and \(\varPi _{it}\) profits. Since the model considers changes in dividend payments over time, it is sometimes also referred to as the partial adjustment model of dividends.

Equation (1) serves as the starting point:

with constant \(\alpha \) and error term \(u_{it}\).

The Lintner model postulates that the change in the dividend payment from period \(t-1\) to t is not equal to the difference of dividend payments in \(t-1\) and the desired long-run dividend payment \(DIV^*_{it} = r\varPi _{it}\), but equal to the fraction s thereof (i.e., the trade-off mentioned above).

The idea is that current dividend payments arise as a compromise between the hypothetical, optimal current level of dividend payment \(DIV^*_{it}\) and the dividend payment in the period before \(DIV_{it-1}\). Lintner (1956) observed that firms tend to set a long-run desired payout ratio r which determines the share of profits which is paid out to shareholders in the form of dividends. However, as changes in profits are not always sustainable, managers are reluctant to fully adjust dividend payments to changes in profits \(\varPi _{it}\) since managers are especially unwilling to decrease dividend payments as this would signal that the firm is in a bad state. Therefore, managers only increase dividend payments very carefully to avoid having to return to the initial level. Hence, managers prefer to change dividend payments only gradually if \(\varPi _{it}\) changes. This feature is captured by the smoothing parameter s which dampens the change in the dividend payment related to a change in \(\varPi _{it}\). Note that a stronger taste for a smooth dividend payments stream leads to a smaller smoothing parameter, which might be counter-intuitive in the first moment. However, a larger s increases changes in the dividend payment in response to a deviation of current profits from past profits, while a lower s reduces changes in the dividend payments over time.

In summary, current dividend payments \(DIV_{it}\) are driven by the firm’s profits in t through the pay-out ratio r and the smoothing parameter s which represents the speed of adjustment toward \(DIV^*_{it}\). Dividends are thus not set independently in each period t but are serially correlated. Consequently, a higher r increases dividend payments in t while a higher s increases the impact of current profits on current dividend payments. Equation (2), which I obtain by rearranging (1) and setting \(s=1\), makes this point clearer. In this extreme case, there is no influence of dividend payments in \(t-1\) on t at all:

While this setup might suggest, at first glance, that the adjustment of dividend payments is equally flexible for increases and decreases, Lintner (1956) expected that firm managers would be more reluctant to decrease than to increase dividend payments (as already discussed above). Hence, the Lintner equation includes a constant \(\alpha \) which allows for positive dividend payouts even in cases where profits are negative.

The error term \(u_{it}\) is sometimes modeled as \(u_{it} = \eta _i + \phi _t + \epsilon _{it}\) to allow for firm fixed effects \(\eta _i\) and aggregate time shocks \(\phi _t\) (like in, e.g., Bellak and Leibrecht 2010). \(\eta _i\) might, for example, reflect firm-specific distastes of reducing the dividend payments. I allow for this specification of the error term in the econometric analysis.

Following Lehmann and Mody (2004), an alternative approach to derive the Lintner model as represented in (2) is based on the minimization of the following loss function:

The first term captures the goal to adjust the actual dividend payment to the desired long-run dividend payment while the second term incorporates the disutility of a volatile dividend payment stream. The parameters \(\phi _1\) and \(\phi _2\) represent the weights firms place on these two objectives. Minimizing the loss function with respect to \(DIV_{it}\) yields

Normalizing the sum of the weights \(\phi _1\) and \(\phi _2\) to 1 produces (2) (if we add the constant \(\alpha \) to account for the reluctance of managers to reduce dividend payments as above, and the error term \(u_{it}\)).

Note that the Lintner model has not only been used to model dividend payments of firms to shareholders but also in the context of intra-firm dividend payments like it is the focus of this paper (see, e.g., Desai et al. 2002).

3.3 The Lintner model extended

According to the basic setup of the Lintner model, current and previous profits are the only determinants of dividend payments of firms. This becomes obvious if (2) is solved recursively. However, there might be further firm and country characteristics like taxes that determine dividend payments. In the following, the model is augmented to allow for these additional factors.

There are different ways to augment the Lintner model. I follow Bellak and Leibrecht (2010) in extending the model utilizing the function \(DIV^*_{it}=r\varPi ^*_{it}\). Besides the optimal payout (\(r\varPi _{it}\)), I add investor-level income taxes (\(TAX_{kt}\))Footnote 2 and further country characteristics (\(\mathbf {X_{kt}}\)) of the country k where the GUO is located, as well as characteristics of firm i (\(\mathbf {X_{it}}\)) and country characteristics of country j (\(\mathbf {X_{jt}}\)) which is the location of firm i:Footnote 3

The intuition behind extending the model utilizing the function \(DIV^*_{it}=r\varPi ^*_{it}\) is that, as argued above, \(DIV_{it}\) is a blend of \(DIV_{it-1}\) and \(DIV^*_{it}\). If changes to the business environment lead to a change in the dividend setting behavior, they will be driven by adjustments of \(DIV^*_{it}\) as \(DIV_{it-1}\) has already been set in \(t-1\). Note that I do not restrict the effect of \(TAX_{kt}\) to have a certain functional form since this effect might depend on the initial level of the tax rate (as argued above). Rather, I am using nonparametric techniques to estimate the effect of the dividend income tax on dividend payouts. Defining \(g(\cdot ) \equiv sf(\cdot )\), Equation (5) can be rearranged to

Equations (2) and (6) serve as the basis for the econometric analysis. In the following, I will discuss how these equations are implemented empirically.

4 Empirical implementation

4.1 Basic Lintner

In a first step, I estimate the basic Lintner model to compare the results of the Lintner parametersFootnote 4 to the literature and hence to evaluate how the model performs in the context of data on MNFs. Furthermore, these results serve as a benchmark for the estimations where I include the tax rates. The basic Lintner model is based on Eq. (2) and is estimated using standard OLS:

The smoothing parameter s and the optimal payout ratio r are then given by

In some specifications, I allow for aggregate time shocks \(\phi _t\) and firm fixed effects \(\eta _i\) in the error component, as discussed above: \(u_{it} = \eta _i + \phi _t + \epsilon _{it}\).

4.2 The Baltagi-Li estimator

It is ex-ante unclear which functional form the dividend tax effect follows. Without imposing any parametric specification on this functional form, I estimate the following equation:

which is based on Equation (6).

Again, I allow for aggregate time shocks \(\phi _t\) and firm fixed effects \(\eta _i\) in the error component: \(u_{it} = \eta _i + \phi _t + \epsilon _{it}\). The estimation of \(g(TAX_{kt}\)) is based on nonparametric methods to circumvent ex-ante restrictions on the functional form. The semiparametric Baltagi-Li estimator introduced by Baltagi and Li (2002) is well suited to be applied to this fixed effect semiparametric panel data modelFootnote 5.

The firm fixed effects \(\eta _i\) are eliminated by first differences which yields

The main idea is to approximate the function \(g(z_t)\) with variable \(z_t\) by a series \(p^k(z_t)\), and hence to approximate \(G(z_{t},z_{t-1})=\{g(z_t)-g(z_{t-1})\}\) by \(p^k(z_{t},z_{t-1})=\{p^k(z_t)-p^k(z_{t-1})\}\), where \(p^k(z_t)\) is a sequence of k functions \([p_1(z_t),p_2(z_t),...,p_k(z_t)]\).

As proposed by Libois and Verardi (2013), this series is estimated through linear B-spline series. For an intuitive explanation on regression splines, please refer to “Appendix.”

Coming back to Eq.(10), Baltagi and Li (2002) show that the parametric part is estimated under the standard \(\sqrt{N}\) normality. While the speed of convergence is smaller for the nonparametric estimate, this will not be a problem in the context of this analysis due to the size of the dataset.

I obtain the coefficients from the parametric part after estimating the following equation:

If I use the result of this estimation to calculate the intercept \({\hat{\alpha }}\) subsequently,Footnote 6 I may estimate \(g(TAX_{kt})\) according to the following equation:

4.3 Instrumental variable strategy

If the estimators were implemented as introduced thus far, the results would be biased since I estimate a dynamic model with fixed effects (see, e.g., Wooldridge 2010). Following Anderson and Hsiao (1982), I instrument \(DIV_{it-1}\) by \(DIV_{it-2}\).

4.4 Further issues

As already discussed above, the basic Lintner model assumes only lagged dividend payments and current profits to determine dividend payments. Therefore, I first provide the results of the basic Lintner model with and without firm fixed effects and time fixed effects, as well as with and without the \(DTR_{kt}\).Footnote 7 I then move on to present the results from the Baltagi-Li estimator. Following standard procedures, I use fourth-degree B-splines; optimal knots are chosen as described in Newson (2000). Equation (12) is then estimated by a kernel density using Epanechnikov kernels. I scale dividend payments (as in, e.g., La Porta et al. 2000; Fama and French 2002); however, following the discussion in La Porta et al. (2000), I use turnover instead of assets. While assets are suitable if all firm observations are located in the same country, turnover is preferable if firms from different countries are considered. The main idea is that, compared to assets, turnover is less sensitive to differences in accounting standards and manipulative accounting practices across countries. Scaled variables are indicated by superscript S (e.g., \(DIV^S_{it}\)).

5 Data

5.1 Dividend income tax data

Most countries do not only levy taxes on earned income but also on capital income such as dividends. While some countries subsume all incomes together for tax purposes, about half of the countries have introduced separate taxes on capital income. Hence, it would not be appropriate to focus on earned income taxes. Therefore, I use the \(DTR_{kt}\) from the income tax dataset by Eklund and Wamser (2019) which provides a large range of different income taxes for 165 countries.

There are different ways of how countries collect dividend income taxes. In France, for example, taxpayers have to declare their dividend income to the tax authorities at the end of the year, which is in contrast to Germany that taxes capital income at source with a flat tax rate. Social security contributions are often levied at lower rates compared to the contributions on earned income.

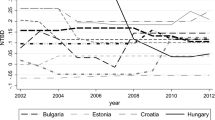

The average \(DTR_{kt}\) equals 17.11% which is much smaller than the average tax rate on earned income (31.99%). Over the last decade, countries have decreased their \(DTRs_{kt}\) by approximately 1 percentage point on average (18.17% in 2006, 17.06% in 2015). However, I observe strong within-country variation as shown in Figure 1. For a more in-depth analysis, see Eklund and Wamser (2019).

5.2 Dividend payout data

I base my empirical analysis on financial firm-level data which I take from the ORBIS dataset provided by Bureau van Dijk. This dataset is well-suited for my analysis due to three different reasons: First, it provides detailed firm-level balance sheet data which allows me to calculate yearly dividend payments. Furthermore, it provides information on the ownership structure of the observed firms. Lastly, the raw dataset covers a vast number of different firms (about 280 million) in numerous countries.

I use information from the balance sheet data to calculate dividend payments since they are not directly observable. I follow the approach taken by Bellak and Leibrecht (2010) and Egger et al. (2015) where dividends follow from the difference between shareholder funds after current profits in \(t-1\) and shareholder funds before current profits in t.Footnote 8 In principle, we can think of shareholder funds as the difference between assets and liabilities (minus minority interests), i.e., a sort of excess wealth which immediately could be handed out the shareholders (ignoring liquidity constraints). Essentially, the approach taken is to compare this excess wealth between two subsequent periods. The difference gives the amount handed out to the shareholders.

One aspect of this paper is to estimate the effect of investor-level dividend income taxes on the repatriation behavior of firms within MNF networks. Hence, for each firm, I need to identify the MNF they belong to, as well as the country where the headquarter of the MNF resides. In ORBIS, this is possible through identifying the so-called GUO.Footnote 9 The GUO is defined as the highest level within an MNF, i.e., the last level of ownership which is not owned by a further firm.

For illustrative reasons, consider the structure of the Volkswagen group. The GUO of this group is the German firm Porsche SE which is primarily owned by the German families Porsche and Piëch. The principal subsidiary of Porsche SE is Volkswagen AG (based in Germany). This firm, in turn, holds Audi AG (based in Germany), which is the owner of Automobili Lamborghini Holding S.p.A. (based in Italy), which is the owner of the Ducati Motor Holding S.p.A (based in Italy). With ORBIS, I am able to identify the home country of the GUO of Ducati Motor Holding S.p.A. which is Germany. This enables me to explore the effect of a change in the German \(DTR_t\) on dividend payments of firms owned by German firms. In the example above, this means identifying changes in the repatriation of profits from Ducati Motor Holding S.p.A. to Automobili Lamborghini Holding S.p.A., from Automobili Lamborghini Holding S.p.A. to Audi AG, from Audi AG to Volkswagen AG and from Volkswagen AG to Porsche SE, as well as payouts of the Porsche SE to the Porsche and Piëch families.

Hence, I am going to use the investor-level dividend income tax rates in the country of the GUO (\(DTR_{kt}\)) as an explanatory variable for dividend payouts of the firms. See Sect. 3.1 for more details.

The analysis includes firms from the manufacturing sectorFootnote 10 which report unconsolidated statements and plausible figures.Footnote 11 Firms which I observe in less than three consecutive years are dropped.Footnote 12 Furthermore, I only include firms for which it is possible to calculate dividend payments. As a result, I end up with 2,133,251 firm-year observations in 67 countries with GUOs in 130 countries between the years 2006 and 2014. Each firm appears on average 7.7 times in the dataset. I observe a GUO for 92.1% of the firms, 21.8% of these GUOs reside in a foreign country (foreign from the perspective of the firm that is owned by the GUO).

5.3 Summary statistics

Figure 2 plots the average \(DIV_{it}\), and Figure 3 the \(DTR_{jt}\) in panel (a) and the average \(DTR_{kt}\)Footnote 13 in panel (b) for each country. The average dividend payment equals USD 3.34 million. I find the largest average \(DIV_{it}\) in South America and Asia where I also find high \(DTRs_{jt}\). On average, the \(DIV_{it}\) in Europe is somewhat smaller while the \(DTRs_{jt}\) is slightly larger. Interestingly, these conclusions do not change if we look at panel (b) where the differences between the \(DTR_{it}\) and the country average of the \(DTR_{kt}\) also are minimal.

While prima facie, one could expect this to be driven by a large number of firms having a GUO in the same country, the difference in the tax rates remains tiny if I only consider firms with foreign GUOs. The difference is only slightly larger (0.2 vs. 1.2 percentage points). Similarly, I find almost the same average tax rates in the countries of the GUOs and in the countries of the firms they own (25.3% and 25.5%). If I look at how \(DTR_{jt}\), \(DTR_{kt}\), and \(DIV_{it}\) correlate, I find a value of 0.8 for the correlation of \(DTR_{jt}\) and \(DTR_{kt}\) while it is almost zero for \(DIV_{it}\) and the two tax rates. The same is true if I consider the correlation of the tax differential between the countries of the firm and the GUO (i.e., \(DTR_{jt}\) - \(DTR_{kt}\)), and \(DIV_{it}\). Interestingly, there is also no significant correlation between \(DIV_{it}\) and the GDP of the countries.

Hence, these first findings do not suggest that changes in dividend payments are associated with changes in income taxes.

Among all firms, I observe zero dividend payments for 41.64% of the firms. I do not find evidence in favor of larger or smaller firms (in terms of assets, profits or turnover) paying zero dividends.

Figure 4 provides a scatterplot of the Lintner variables \(DIV_{it}\), \(DIV_{it-1}\), and \(PL_{it}\) (profits and losses), as well as a linear fit of the data. Many firms pay only relatively small dividends. However, I also observe firms with large payments. I find strong graphical evidence in favor of the Lintner model, higher values of \(PL_{it}\) or \(DIV_{it-1}\) are associated with higher \(DIV_{it}\). Note that for some firms I observe large dividend payments and profits. The results in the econometric analysis are robust to winsorizing (e.g., at the \(1^{st}\) and \(99^{th}\) percentile) or to trimming the data, however.

5.4 Further control data

Some publications in the literature identify no need to include further control variables into the Lintner model (see, e.g., Fama 1974). Nevertheless, in some specifications, I will include further country and firm-specific control variables to check for the robustness of the estimations and also to be consistent with other studies on this topic. Like Bellak and Leibrecht (2010) or Brown et al. (2007), I control for lagged firm debt (\(DEBT_{it}\)), GDP growth in the country of the firm (\(GDP^{g}_{jt}\)) and of the GUO (\(GDP^{g}_{kt}\)), as well as firm size (following, e.g., Benito and Young 2003; Bond et al. 2007). While I use the debt indicator from the ORBIS dataset, I take GDP growth rates from the Worldbank’s World Development Indicators. For the size of the firms, I use turnover (\(TURN_{it}\)) from ORBIS following the argument above (in an international context, this is the most comparable measure available).

Due to the high computational requirements of the Baltagi-Li estimator, I only use a smaller subsample where I keep firms with a total of assets worth at minimum USD 1 million.Footnote 14 I provide evidence that the estimates are not sensitive to this restriction of the sample.Footnote 15

Summary statistics are provided in Table 1 for the full sample and in Table 2 for the sample which only includes firms with at least USD 1 million in assets.

6 Results

In this chapter, I present the results of the econometric analysis. I start with the discussion of the results of the pure basic model. Then, I move on to the effect of the \(DTR_{kt}\) and further control variables on the dividend payments where I also use semiparametric techniques.

6.1 The Lintner model

Column (1) in Table 3 presents the results of the basic Lintner model based on Eq. (7), using the full sample and unscaled variables. I find highly significant and positive coefficients for \(DIV_{it-1}\) and \(PL_{it}\). Using Eq. (8), I may calculate the smoothing parameter s and the desired payout ratio r, as defined in Eq. (1). The results suggest that firms exhibit moderate preferences in favor of a smooth dividend payment stream (\(s=0.7243\))Footnote 16 which suggests that firms are somewhat reluctant to change the dividend payment in response to a change in profits. Furthermore, I estimate the desired long-run payout ratio to be equal to 33.1%. Next, I report the results for firms with at least USD 1 million in assets and firm-specific variables scaled by turnover (as discussed in Sect. 5.2). As can be seen in Column (2), excluding the small firms does not lead to significant changes in the results. If I use the scaled variables (3) and add aggregate year effects (4), I find somewhat larger smoothing parameters and smaller desired payout ratios. Adding firm fixed effects (5), however, generates results which are again more similar to the results in (1) and (2). I will refer to (5) as the preferred specification since the firm and aggregate year effects, as well as the scaling of the variables, have been used in the literature in a very similar way.

As already discussed above, Bellak and Leibrecht (2010) provide an overview of the estimated Lintner parameters in the literature. For dividend payments, the speed of adjustment coefficient ranges from 0.16 to 0.77; the desired payout ratio is estimated to be between 0.23 and 0.88. The estimates of (1) and (2) are within that range. I find somewhat larger smoothing parameters and smaller desired payout ratios in (3) and (4). In the preferred estimation (5), the smoothing parameter is just slightly larger.

However, the results discussed so far do not only suggest that the data fits the Lintner model very well, but I also find reasonable results for the intercept which is either significant and positive or insignificant (firms reduce dividends only reluctantly to avoid clashing with shareholders) but not negative, as predicted by the Lintner model. A significant negative coefficient would have called my approach into question since it would have suggested that firms only reluctantly increase dividends, which is very unlikely. Overall, I conclude that the results strongly support the econometric approach I have chosen and provided a sensible foundation to investigate the effect of the \(DTR_{kt}\) on dividend payments, which I discuss in the next part.

6.2 Dividend payments and taxes

Table 4 presents the results of the specifications where I additionally include the \(DTR_{kt}\) and further control variables. I start by adding the \(DTR_{kt}\) to the preferred Lintner specification, with and without aggregate year fixed effects. Furthermore, I add the additional control variables as discussed in 5.4. The results are presented in columns (1)–(3). Adding the \(DTR_{kt}\) keeps the Lintner parameters completely unchanged, adding the additional controls gives only rise to slight adjustments. I find a significant negative effect of firm debt, all other additional variables, as well as the intercept, are insignificant.

However, the fact that the \(DTR_{kt}\) remains highly insignificant in all three specificationsFootnote 17 is the most important finding. This result serves as a further piece of evidence that firms do not base their dividend payment decisions on investor-level income taxes.

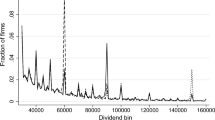

As discussed above, it is ex-ante unclear if the parametric functional form I impose on the \(DTR_{kt}\) is valid. Therefore, I repeat the econometric analysis above where I estimate the effect of the \(DTR_{kt}\) nonparametrically using the Baltagi-Li estimator, as discussed in Sect. 4 (I report the results in columns (4)–(6)). The first thing I note is that the smoothing parameter decreases a bit while the desired payout ratio is virtually unchanged. Therewith, both parameters are fully in line with previous results in the literature. Adding aggregated time shocks and additional control variables only changes these results fractionally. I present the nonparametric results of the estimate of the \(DTR_{kt}\) in Fig. 5 panel (a). What we see is that, again, the effect of the \(DTR_{kt}\) is very small over the whole range. Furthermore, the effects are much smaller compared to the (insignificant) estimates in the parametric specification for each value of the \(DTR_{kt}\). Nevertheless, I find positive effects for very small values which is puzzling.

While the similarity of these results with the parametric ones suggests that the semiparametric findings of the tax rates also might be highly insignificant, I would need to estimate the standard deviations of the estimated parameters in order to come up with a more reliable statement. Since this is not even computationally feasible for the subsample with the firms with at least USD 1 million in assets, I repeat the estimation using firms with at least USD 5 million in assets. Subsequently, I plot the nonparametric estimate as well as the 95% confidence interval in Fig. 5, panel (b). The results indicate the tax effect not to be significantly different from zero over the whole range. Hence, I still may conclude that the \(DTR_{kt}\) does not play a significant role in the decision of intra-firm dividend payments at any level of the tax rate.

7 Robustness checks

This chapter covers the robustness checks I have conducted in order to examine the sensitivity of the results. Some first evidence has already been presented in Sect. 6.1 where I show the results for the specifications with unscaled variables, and the full sample including small firms.

In a next step, I consider the approach taken by Bellak and Leibrecht (2010) who set dividend payments equal to zero where they observe zero profits or losses. The results can be found in column (1) in Table 5 (which also covers the other specifications I discuss in this section henceforth in columns (2)–(7)). I find similar results in terms of the Lintner parameters and the \(DTR_{kt}\), the latter still being insignificant. In a further step, I additionally exclude firms where dividend payments exceed profits. The tax coefficient remains insignificant; the smoothing parameter s decreases somewhat.

For the next four specifications, I do not find any changes in the Lintner parameters compared to (1). In (3), I use the investor-level dividend tax rate in the country where the subsidiary resides (\(DTR_{jt}\)), in (4), I include the \(DTR_{kt}\) as well as the \(DTR_{jt}\). All tax coefficients remain insignificant. Hence, I do not find any evidence that multinational firms base their dividend payments on investor-level tax rates in the country of the firms. In some countries, there are possibilities for investors to retain dividend earnings for reinvestment such that the capital income is finally taxed at the capital gain tax rate (\(CGTR_{kt}\)). Using the \(CGTR_{kt}\)Footnote 18, which I also take from Eklund and Wamser (2019), I still do not find a significant effect of the tax (as reported in column (5)), the same is true if I use the \(CGTR_{jk}\) (6). Since the data include firms with GUOs in the same country, as well as in a different country, I also test a specification where I include an interaction term of the \(DTR_{kt}\) with an indicator which is one if the subsidiary and the GUO are in different countries (column (7)). Also here, I do not find any significant effects of the dividend income tax rate. These findings underline that firms not only leave dividend payments unchanged but also repatriate profits from foreign firms they own in the same way as they did before taxes changed. Column (8) only includes firms located in the European Union. The results suggest that only looking at firms located within the European Union does not imply any underlying differences. Following the discussion in chapter 5.2 and in footnote 10, all estimations only include firms from the manufacturing sector. Column (9) includes all firms, e.g., financial companies or funds. Results remain robust to inclusion of all these firms. Again, the results are in line with what we have found before. Finally, note that the results are robust to winsorizing (e.g., at the \(1^{st}\) and \(99^{th}\) percentile) or to trimming the data.

8 Conclusion

This study evaluates the effect of investor-level dividend income taxes on dividend payments of firms. While firms might change dividend payments to investors in response to a tax change, I do also take into account that this change in dividend payments might lead to adjustments of the repatriation of profits from other firms which the firm owns. I base my analysis on the Lintner model of dividend payouts. In a first step, I show that consistently with the literature dividend payments result as a combination between the desired payout ratio and dividend payments in the period before, since firms aim at providing with a smooth dividend payment stream. In a next step, I add different control variables and the dividend tax rate. While I deploy full parametric models, I also allow for heterogeneous effects of the tax using the semiparametric Baltagi-Li estimator. In a third step, I present the results of various robustness checks including alternative specifications and subsamples of the data.

All results consistently show that dividend income taxes on the level of investors do not have a significant impact on dividend payments of firms, neither on payments to investors nor on intra-MNF profit repatriations. This finding is robust if I use the tax rate of the subsidiary instead of the parent company. The same is true for the capital gains tax rate.

Furthermore, this study contributes to the literature by producing evidence that the Lintner model provides sensible results in a setting that includes large numbers of countries and firms that belong to MNF networks.

These findings have important implications for public policies. Most countries levy considerably smaller taxes on investor-level capital income compared to earned income. While there are various reasons for this difference, some countries do so because of fears that higher taxes might induce capital flights. The results of this study provide evidence that the cost of increasing the dividend income tax might be smaller than initially assumed.

There might also be implications from this paper on the current debates to impose global minimum corporate income taxes. In some instances, investor-level dividend income taxes are interpreted as part of the corporate income tax. If legislator changes the corporate income tax rate, there might also be changes to investor-level dividend income taxes. Specifically, the investor-level dividend income tax differential across countries could be increased simultaneously. Naturally, these implications depend on the specific design after implementation. Nevertheless, following the results of insignificant effects of the investor-level taxation part, a global minimum corporate income tax could still have limited effects in the context of this paper. It could be interesting for future research to consider these effects in depth.

This study also has some important limitations. While I observe the location of the mother company, I do not observe the country of residence of the most influential investors, i.e., I assume that they reside in the same country as the mother company within an MNF network. However, if these investors are taxed in different countries, firms might adjust their dividend payments according to some weighted average of the tax rate of the different countries. However, since studies (e.g., French and Poterba 1991) have shown that there is an investment home bias (i.e., investors tend to invest disproportionally in the home market), the tax rate in the country of the firm could still serve as an instrument for the weighted average tax rate. Furthermore, the characteristics of investors could lead to a slight deviation from the standard tax rate in some countries. Hence, this research could be extended by including information on the influential shareholders themselves which would improve the precision of the approach taken.

Notes

In the US, firms are categorized in into C- and S-corporations. The only major difference is the fact that C-corporations are subject to dividend taxation while S-corporations are not.

Since the focus of the paper is on the dividend tax rate, I use the abbreviation of the dividend tax rate (\(DTR_{kt}\)) in most sections. However, since I also estimate specifications with the tax rate on capital gains (\(CGTR_{kt}\)), I use (\(TAX_{kt}\)) in the model as a more general abbreviation for taxes.

i.e., the GUO and the affiliate may but do not necessarily have to be in the same country.

The Lintner parameters refer to the smoothing parameter and the long-run desired payout ratio as defined in the model.

Using Eqs. (10) and (12), we see that \(\omega \) secures the following equality: \(\omega p^k(TAX_{kt})=g(TAX_{kt})\). Therewith, I can construct the intercept: \({\hat{\alpha }}=DIV_{it}-\hat{\beta _1} \varPi _{it} - \hat{\beta _2} DIV_{it-1} - {\hat{\omega }} p^k(TAX_{kt}) - \varvec{\hat{\beta _3} X_{it}} - \varvec{\hat{\beta _4} X_{jt}} - \varvec{\hat{\beta _5} X_{kt}}\).

Recall that I abbreviate the dividend tax rate in time t in country k (i.e., the country of the GUO) by \(DTR_{kt}\).

More specifically, I calculate dividends according to the following formula: \(DIV_{it}=SHFD_{it-1} + PL_{it-1} - SHFD_{it}\) where \(DIV_{it}\) denotes dividends, \(SHFD_{it}\) available shareholder funds for distribution and \(PL_{it}\) current profits of firm i in period t. Negative values are set to zero as in Egger et al. (2015).

Recall that the abbreviation GUO refers to the global ultimate owner.

Therewith, I exclude the following type of firms: Banks, financial companies, foundation and research institutes, insurance companies, funds, public authorities, and venture capital firms. These firms are excluded because of regulatory differences (as in, e.g., Duchin and Sosyura 2013).

I drop firms if the balance sheets report negative stocks of assets or negative values for cash or turnover. Note that I also conduct estimations where I trim or winsorize the data in the robustness checks (Sect. 7).

Note that only observations from 2007 will end up in the estimations since I need one observation in \(t-1\) to calculate \(DIV_{it}\). Furthermore, the Lintner model includes one lag of \(DIV_{it}\). Hence, I need at least three consecutive observations of a firm to include it successfully in the empirical estimations.

Assume two firms are located in country A. Further assume, the \(DTR_{t}\) in the two countries of the firms’ GUOs are equal to 0.2 and 0.3, respectively. Therewith, I assign \(DTR_{kt}=0.25\) to country A.

Note that I already use the bwHPC high performance computing cluster provided by Baden-Württemberg’s ministry of science to carry out the estimations.

To be more specific, I estimate the standard Lintner model by means of OLS using the restricted and the unrestricted sample. The results are virtually identical.

Recall that larger smoothing parameters imply smaller preferences for dividend smoothing.

Apart from being insignificant, the size of the estimated coefficient might be surprising; however, note that a tax rate of 20% is coded as 0.2 in the data and not as 20.

i.e., the \(CGTR_t\) in the country of the GUO.

Runge’s phenomenon describes the effect of potential low precision of an estimate which relies on a high-order polynomial. One reason is that for a high-order polynomial, the function may start to oscillate as the value of the derivatives increase.

References

Aivazian VA, Booth L, Cleary S (2006) Dividend smoothing and debt ratings. J Financ Quant Anal 41(2):439–453

Alstadsæter A, Jacob M, Michaely R (2017) Do dividend taxes affect corporate investment? J Public Econom 151:74–83

Altshuler R, Grubert H (2003) Repatriation taxes, repatriation strategies and multinational financial policy. J Public Econom 87(1):73–107

Ambarish R, John K, Williams J (1987) Efficient signalling with dividends and investments. J Financ 42(2):321–343

Anderson TW, Hsiao C (1982) Formulation and estimation of dynamic models using panel data. J Econom 18(1):47–82

Atkin D, Khandelwal AK, Osman A (2017) Exporting and firm performance: evidence from a randomized experiment. Q J Econom 132(2):551–615

Babiak H, Fama EF (1968) Dividend policy: an empirical analysis. J Am statist Assoc 63:1132–1161

Baglan D, Yoldas E (2014) Non-linearity in the inflation-growth relationship in developing economies: evidence from a semiparametric panel model. Econom Lett 125(1):93–96

Baltagi BH, Li D (2002) Series estimation of partially linear panel data models with fixed effects. Ann Econom Financ 3(1):103–116

Bellak C, Leibrecht M (2010) Does lowering dividend tax rates increase dividends repatriated? evidence of intrafirm cross-border dividend repatriation policies by german multinational enterprises. Finanzarchiv 66(4):350–383

Benito A, Young G (2003) Hard times or great expectations? dividend omissions and dividend cuts by uk firms. Oxford bull Econom statist 65(5):531–555

Black F (1976) The dividend puzzle. J Portfolio Manage 2(2):5–8

Bond S, Devereux M, Klemm A (2007) Dissecting dividend decisions: some clues about the effects of dividend taxation from recent uk reforms. In: Auerbach AJ, Hines JR, Slemrod J (eds) Taxing corporate income in the 21st century. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

de Boor C (1972) On calculating with b-splines. J Approxim Theory 6(1):50–62

de Boor C (2001) A practical guide to splines. Springer, New York

Brennan M (1971) A note on dividend irrelevance and the gordon valuation model. J Financ 26(5):1115–1121

Brown JR, Liang N, Weisbrenner S (2007) Executive financial incentives and payout policy: firm responses to the 2003 dividend tax cut. J Financ 62(4):1935–1965

Chetty R, Saez E (2005) Dividend taxes and corporate behavior: evidence from the 2003 dividend tax cut. Q J Econom 120(3):791–833

Clemens MA, Lewis E, Postel H (2018) Immigration restrictions as active labor market policy: evidence from the mexican bracero exclusion. Am Econom Rev 108(6):1468–1487

Desai MA, Foley CF, Hines JR (2002) Repatriation taxes and dividend distortions. National Tax J 54(4):829–851

Desai MA, Foley CF, Hines JR (2007) Dividend policy inside the multinational firm. Financ Manage 36(1):5–26

Desbordes R, Verardi V (2012) Refitting the kuznets curve. Econom Lett 116(2):258–261

Duchin R, Sosyura D (2013) Divisional managers and internal capital markets. J Financ 68(2):387–429

Egger P, Merlo V, Ruf M, Wamser G (2015) Consequences of the new uk tax exemption system: evidence from micro-level data. Econom J 125(589):1764–1789

Eklund MJC, Wamser G (2019) Top income taxes around the world. Unpublished manuscript

Fama EF (1974) The empirical relationships between the dividend and investment decisions of firms. Am Econom Rev 64(3):304–318

Fama EF, French KR (2002) Testing trade-off and pecking order predictions about dividends and debt. Rev Financ Stud 15(1):1–33

Fernau E, Hirsch S (2019) What drives dividend smoothing? a meta regression analysis of the lintner model. Int Rev Financ Anal 61:255–273

French KR, Poterba JM (1991) Investor diversification and international equity markets. Am Econom Rev 81(2):222–226

Grubert H (1998) Taxes and the division of foreign operating income among royalties, interest, dividends and retained earnings. J Public Econom 68(2):269–290

Hanlon M, Hoopes JL (2014) What do firms do when dividend tax rates change? an examination of alternative payout responses. J Financ Econom 114(1):105–124

Hanlon M, Lester R, Verdi R (2015) The effect of repatriation tax costs on u.s. multinational investment. J Financ Econom 116(1):179–196

John K, Williams J (1985) Dividends, dilution, and taxes: a signalling equilibrium. J Financ 40(4):1053–1070

La Porta R, Lopez-de Silanes F, Shleifer A, Vishny RW (2000) Agency problems and dividend policies around the world. J Financ 55(1):1–33

Lehmann A, Mody A (2004) International dividend repatriations. IMF working paper no 04/5

Lessmann C (2014) Spatial inequality and development: Is there an inverted-u relationship? J Develop Econom 106:35–51

Libois F, Verardi V (2013) Semiparametric fixed-effects estimator. Stat J 13(2):329–336

Lintner J (1956) Distribution of incomes of corporations among dividends, retained earnings, and taxes. Am Econom Rev 46(2):97–118

Miller MH, Rock K (1985) Dividend policy under asymmetric information. J Financ 40(4):1031–1051

Modigliani F, Miller MH (1958) The cost of capital, corporation finance and the theory of investment. Am Econom Rev 48(3):261–297

Newson R (2000) Bspline: Stata modules to compute b-splines parameterized by their values at reference points. https://ideas.repec.org/c/boc/bocode/s411701.html

Poterba JM (2004) Taxation and corporate payout policy. Am Econom Rev 94(2):171–175

Powell GE (2009) Cash dividends and stock repurchases. In: Baker HK (ed) Dividends and dividend policy, vol 40. The Robert W. Kolb series in finance. Wiley, Hoboken, New Jersey, pp 363–383

Powell MJD (1981) Approximation theory and methods. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Ross S (1977) The determination of financial structure: the incentive-signalling approach. Bell J Econom 8(1):23–40

Shefrin HM, Statman M (1984) Explaining investor preference for cash dividends. J Financ Econom 13(2):253–282

Wooldridge JM (2010) Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data, 2nd edn. MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts

Yagan D (2015) Capital tax reform and the real economy: the effects of the 2003 dividend tax cut. Am Econom Rev 105(12):3531–3563

Zhu H, You W, Zeng Z (2012) Urbanization and co2 emissions: a semi-parametric panel data analysis. Econom Lett 117(3):848–850

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Comments and suggestions by Valeria Merlo, Georg Wamser, Simon Behrendt, Sandra Kohler, the editor in charge (Bertrand Candelon) and the anonymous reviewers are gratefully acknowledged. The author acknowledges support by the state of Baden-Württemberg through bwHPC.

Appendices

Appendix

Tables

Figures

Nonparametric results \(DTR_{kt}\). Notes This figure provides in a the nonparametric results of the \(DTR_{kt}\) from the estimations presented in Table 4, columns (4)–(6). In b, I also present the 95% confidence interval. Due to computational restrictions, this estimation is based on a restricted sample including only firms with assets \(\ge \) USD 5 million

Nonparametric estimation

The function \(g(z_t)\) is approximated by a series \(p^k(z_t)\), the estimation is carried out through a B-spline series. Intuitively, using regression splines amounts to splitting the data into bins where each bin is fitted individually by a polynomial function. Therefore, each bin can be fitted by a simpler polynomial instead of using a complex polynomial over the whole range which might explain the data poorly and could suffer from Runge’s phenomenon.Footnote 19 To ensure that this procedure results in a smooth piecewise polynomial function, the different polynomials have to meet properly at each border of each bin (called knots). In formal terms, the function itself and the first \(m-1\) derivatives have to meet continuously at each knot.

For illustrative reasons, a spline series of degree m with k knots \(c_1<c_2<\cdots <c_k\) can be represented using a power series:

For example, if we set \(m=2\) and \(k=4\), evaluate the function at any value \(z_t\) with \(c_2 \le z_t \le c_3\) and reorder, this results in

If we subsequently set \(z_t=c_2\) and do the same for \(S(z_t)\big |_{c_1 \le z_t \le c_2}\), we would have that

which shows that the functions meet smoothly.

The same is true for the first derivative. Hence, the different polynomials meet continuously at the knots. Furthermore, note that three conditions are needed to identify a second-order polynomial unambiguously. The first two conditions are given by the requirement that the first and second derivative have to join smoothly at \(c_1\). These conditions are determined by the parameters resulting from the former bins (here: the bin below \(c_1\) and the bin between \(c_1\) and \(c_2\)): \(\zeta _0\), \(\zeta _1\), \(\zeta _2\), \(\lambda _1\). Hence, there is precisely one free parameter left which may be determined by the data of the local bin: \(\lambda _2\). Therefore, at each bin, the parameters arise as a compromise between the local data and the surrounding polynomials.

While spline series estimation based on power functions is a very intuitive concept, especially to motivate how the different parts meet continuously at the knots, it might suffer from computational issues. The polynomials might become almost collinear if bins are too small. Furthermore, small bins can lead to overflow errors in the numerical estimation procedure. This problem may be solved if B-spline bases are chosen instead of truncated polynomials. First, it is important to note that B-splines are more flexible since they can represent any spline series using linear combinations. In effect, B-splines can be thought of as a rescaling of the piecewise functions. B-splines are based on Bézier curves. Essentially, Bézier curves are built from a series of control points which are weighted by Bernstein polynomials. The following drawing shows how three control points \(P_1\), \(P_2\) and \(P_3\) define a quadratic Bézier curve (The thick curve connecting \(P_1\) and \(P_3\)):

Intuitively, these Bézier curves are then put together to construct the B-spline series. Technically, the Cox-de Boor recursion formula is used to combine the Bézier curves. For more details, the interested reader is referred to de Boor (1972), Powell (1981) or de Boor (2001).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Eklund, M.J.C. Do multinational firms respond to personal dividend income tax rates?. Empir Econ 62, 1743–1771 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-021-02088-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-021-02088-2