Abstract

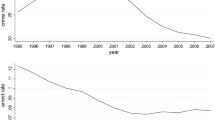

This paper examines the association between racial demographics and the shifting of cigarette excise taxes to consumer prices. Using scanner data on cigarette sales from 1687 stores across 53 American cities, 2009–2011, we found that cigarette taxes are shifted significantly less to consumer prices in cities with large minority (black and Hispanic) populations. The potential for price search behavior implies that our estimates understate the magnitude of the true relationship between local racial composition and cigarette tax shifting. Our finding suggests that increasing cigarette taxes may not be an effective means of reducing cigarette consumption in high-minority areas.

Source: Authors’ calculation

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The death rate from lung cancer among black men is 21% higher than white men (American Cancer Society 2015).

2016 National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Report. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. http://www.ahrq.gov/research/findings/nhqrdr/nhqdr16/index.html.

The IRI is one of two major vendors of supermarket scanner data (along with A.C. Nielsen).

For instance, using Nielsen Homescan data, Harding et al. (2012) concluded that cigarette taxes are passed through less to consumer price if consumers live closer to a lower-tax border. Using data from the Current Population Survey (2003 and 2006–2007), DeCicca et al. (2013) found that price search behaviors—that is, buying cartons instead of packs—significantly reduce the shifting of cigarette excise taxes to consumer prices.

A potential concern with this comparison is that smoking rates are lower among Hispanics. According to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2015), smoking rates for Hispanics (11%) are lower than whites and blacks (both roughly 18%). By definition, lower levels of smoking lead to larger elasticity estimates (in absolute values). Thus, even if the price elasticity of demand appears larger among Hispanics, the price responsiveness may not vary much between whites and Hispanics.

Maclean et al. (2013) suggested that living in ethnic enclaves may allow more opportunity to obtain untaxed cigarettes. For instance, a large tax increase in New York City led to pervasive illegal cigarette markets in black and Hispanic communities (Coady 2013). Using focus groups study, Shelley et al. (2007) documented large-scale purchasing of untaxed cigarettes in Central Harlem in New York City—a phenomenon known as the “5 dollar man.”

Since 2008, IRI has made available to researchers detailed transaction-level data spanning 30 categories of products, including cigarette product. See Bronnenberg et al. (2008) for further details on the data.

We computed the monthly prices by averaging weekly prices over a month. This does not undermine the virtue of disaggregate level information because relatively little variation in prices is observed within a month.

In some states, localities impose excise taxes on cigarettes in addition to the state tax. With a few exceptions [e.g., Chicago and Cook County (Illinois) and New York City (New York)], however, the local taxes are relatively small (DeCicca et al. 2013).

For confidentiality reasons, IRI does not report the data collected from markets where only a few chains have dominant market shares (because chain names would be easily identified). Out of the available data, we exclude the stores (in Maine, New Hampshire, and Vermont) for which the geographic market is ambiguously defined by IRI. This reduces our sample to 1687 stores in 28 states.

Summary statistics of key demographic variables are similar between included and excluded states.

Lovenheim (2008) and Harding et al. (2012) computed the distance from each census tract to a road crossing into the lower-tax state. Callison and Kaestner (2014) used Google Maps API to measure the distance to the nearest lower-tax border. In our paper, border locations are measured by a set of geographical coordinates of the line segments that make up the state borders (see Holmes (1998) for further details). The estimates for our distance measure are consistent with the findings of previous literature.

In addition, although Seattle is larger and wealthier than Tacoma (e.g., more than three times larger in population), the pass-through rate in Seattle ($1.00) is close to the pass-through rate in Tacoma ($0.99). This is consistent with the fact that the shares of black population in the two cities are relatively similar (i.e., 8% in Seattle and 11% in Tacoma).

Alternatively, we could include store fixed effects rather than chain fixed effects. In our data, however, price variation across stores within a chain for each UPC (in each city and month) is much smaller than the price variation across chains—suggesting that the chain fixed effects better capture pricing behavior. The average coefficient of variation (ratio of standard deviation to mean) is 7.05% for variation across chains but only 0.29% for variation across stores of the same chain. Using the Nielsen scanner data, Hitsch et al. (2017) also found that retail prices and promotions are relatively homogeneous across stores belonging to the same retail chain.

We also controlled for the number of stores operating within varied thresholds of the radius as a proxy variable for price competition. The estimates were insignificant, however, and the coefficients of tax shifting barely changed (not reported). This indicates that the chain fixed effects capture most of the competition effects.

Another possibility is that sellers might offset anti-smoking regulations by lowering prices (Keeler et al. 1996).

The baseline assumption underlying our empirical model is that there are time-invariant unobserved effects on cigarette prices (across products, chains, and states) that are correlated with the observed regressors such as demographics, distance to the lower-tax state, and taxes. To deal with the potential endogeneity, we use the fixed effects model. Thus, the key identifying assumption is that only the observed regressors affect the expected value of cigarette prices once the fixed effects are controlled for. Section 3.3 shows that our results are robust to various specifications of the fixed effects model.

As indirect evidence, the cross-city variation in prices (measured by the coefficient of variation) is 4.7% overall while the within-city variation is only 2.6%. (The cross-city variation in prices is restricted to the same state.)

The estimates of pass-through rate in columns 2 and 3 are statistically different from one another. In addition, all the coefficients for chain dummies are statistically different from zero.

Adding only demographic variables without border effects has little impact on tax shifting—that is, the pass-through rate does not change significantly from that in column 3. This result does not imply that the demographic variables are unrelated with the pass-through rate, but simply means that time, state, chain, and UPC fixed effects sufficiently control for store pricing behaviors that are associated with cigarette taxes and demographic profiles (Harding et al. 2012). We show in Table 4 that racial demographics indeed have a significant impact on pass-through rates.

Our sample cities do not include Native American reservations that sell lower price cigarettes.

As an alternative measure of racial composition, we have computed the Herfindahl index as the degree of diversity, using eight racial/ethnic categories: white, black, Asian, Hispanic, Native American and Native Alaskan, Hawaiian and Pacific Islander, mixed, and other. The diversity index shows the probability of two randomly drawn people in the city to be of different racial/ethnic groups, ranging from 0 (complete homogeneity) to 1 (complete heterogeneity). The correlation between the diversity index and the share of white population is \(-0.56\). Not surprisingly, we obtained a similar result: that tax shifting decreases with the index of diversity (not reported). As is well known, however, the diversity index does not take into account the composition of specific racial groups, so the index gives the same score whether the city has 70% white and 30% black or 30% white and 70% black.

The pass-through estimate of 0.963 is obtained by 16.168 − 0.329 \(+\) 0.010 \(\times \) (mean of log distance to the lower-tax border) − 0.975 \(\times \) (mean Black share) − 1.238 \(\times \) (mean Hispanic share) \(+\) 1.880 \(\times \) (mean Asian share) − 0.610 \(\times \) (mean Native share) − 2.502 \(\times \) (mean Mixed share) \(+\) 9.237 \(\times \) (mean Other share) − 1.367 \(\times \) (mean of log median income)—based on column 3 (Table 4). Note that population shares of non-black minority groups and income levels are held constant at the mean level.

The median household income and the distance from the lower-tax border are held constant at the sample mean values.

Demographics are collected at the level of Zip Code Tabulation Area (ZCTA) from the US Census Bureau.

We also used the population shares of minority groups at the census tract level. The results (not reported) show that the potential for price search behavior across census tracts (with a population size ranging between 1200 and 8000) also leads to biased estimates of the magnitude of the relationship between local racial composition and cigarette tax shifting.

The intensity of tobacco counter-marketing media campaigns is measured by the gross rating points (GRPs). GRPs are defined as total reach (i.e., the total number of households that could potentially be exposed to an ad campaign) multiplied by frequency of exposure to the ad (i.e., the number of times households in a given media market are exposed to the ads in a given time frame). GRPs are averaged across media markets in each state for 2010. See the Tobacco Control State Highlights 2012 (issued by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) for more details on the variables.

Most of the demographic variables in our data have substantial variations across markets within each state.

Because smoking rates by city are not available, we construct a measure of smoking rates based on cigarette sales by city using the scanner data. Specifically, we define the pre-tax smoking rates as the monthly sales of cigarettes (in pack) across stores in a city, prior to tax change, divided by the total monthly potential of cigarette consumption. The potential is assumed to be one pack per day per capita for 2-mile-radius population (over age 18) of a store (provided by the IRI).

In panel A, the pass-through rates are now increasing in the share of Hispanics, but the differences are not economically significant.

Approximately 90% of African-Americans smoke menthol cigarettes (Giovino et al. 2015).

References

Adda J, Cornaglia F (2006) Taxes, cigarette consumption, and smoking intensity. Am Econ Rev 96(4):1013–1028

American Cancer Society (2015) Cancer facts & figures 2015. American Cancer Society, Atlanta

Anderson SP, de Palma A, Kreider B (2001) Tax incidence in differentiated product oligopoly. J Public Econ 81(2):173–192

Baluja KF, Park J, Myers D (2003) Inclusion of immigrant status in smoking prevalence statistics. Am J Public Health 93(4):642–646

Barzel Y (1976) An alternative approach to the analysis of taxation. J Polit Econ 84(6):1177–1197

Berry S, Levinsohn J, Pakes A (1995) Automobile prices in market equilibrium. Econometrica 63(4):841–890

Besley TJ, Rosen HS (1999) Sales taxes and prices: an empirical analysis. Natl Tax J 82(2):157–178

Bloom PN (2001) Role of slotting fees and trade promotions in shaping how tobacco is marketed in retail stores. Tob Control 10(4):340–344

Borcherding TT, Silberberg E (1978) Shipping the good apples out: the Alchian and Allen theorem revisited. J Polit Econ 86(1):131–138

Bronnenberg BJ, Kruger MW, Mela CF (2008) The IRI marketing data set. Mark Sci 27(4):745–748

Callison K, Kaestner R (2014) Do higher tobacco taxes reduce adult smoking? New evidence of the effect of recent cigarette tax increases on adult smoking. Econ Inquiry 52(1):155–172

Caraballo RS et al (1998) Racial and ethnic differences in serum cotinine levels of cigarette smokers. J Am Med Assoc 280(2):135–139

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2015) Current cigarette smoking among adults-United States, 2005—2014. Mobil Mortal Wkly Rep 64(44):1233–1240

Chaloupka FJ, Peck R, Tauras JA, Xu X, Yurekli A (2010) Cigarette excise taxation: the impact of tax structure on prices, revenues, and cigarette smoking. NBER Working Paper No. 16287

Chiou L, Muehlegger E (2014) Consumer response to cigarette excise tax changes. Natl Tax J 67(3):621–650

Coady MH et al (2013) The impact of cigarette excise tax increases on purchasing behaviors among New York city smokers. Am J Public Health 103(6):e54–e60

DeCicca P, Kenkel D, Liu F (2013) Who pays cigarette taxes? The impact of consumer price search. Rev Econ Stat 95(2):516–529

Ellickson PB, Misra S (2008) Supermarket pricing strategies. Mark Sci 27(5):811–828

Evans WN, Farrelly MC (1998) The compensating behavior of smokers: taxes, tar, and nicotine. RAND J Econ 29(3):578–595

Farrelly MC, Bray JW, Pechacek T, Woollery T (2001) Response by adults to increases in cigarette prices by sociodemographic characteristics. South Econ J 68(1):156–165

Farrelly MC, Nimsch CT, Hyland A, Cummings MK (2004) The effects of higher cigarette prices on tar and nicotine consumption in a cohort of adult smokers. Health Econ 13(1):49–58

Giovino GA, Villanti AC, Mowery PD et al (2015) Differential trends in cigarette smoking in the USA: Is menthol slowing progress? Tob Control 24:28–37

Goolsbee A, Petrin A (2004) The consumer gains from direct broadcast satellites and the competition with cable TV. Econometrica 72(2):351–381

Goolsbee A, Lovenheim MF, Slemrod J (2010) Playing with fire: cigarettes, taxes, and competition from the internet. Am Econ J Econ Policy 2(1):131–154

Hanson A, Sullivan R (2009) The incidence of tobacco taxation: evidence from geographic micro-level data. Natl Tax J 62(4):677–698

Harding M, Leibtag E, Lovenheim MF (2012) The heterogeneous geographic and socioeconomic incidence of cigarette taxes: evidence from Nielson homescan data. Am Econ J Econ Policy 4(4):169–198

Hitsch GJ, Hortacsu A, Lin X (2017) Prices and promotions in U.S. retail markets: evidence from big data. Chicago Booth Research Paper No. 17-18

Holmes TJ (1998) The effect of state policies on the location of manufacturing: evidence from state borders. J Polit Econ 106(4):667–705

Jia P (2008) What happens when wal-mart comes to town: an empirical analysis of the discount retailing industry. Econometrica 76(6):1263–1316

Johnson TR (1978) Additional evidence on the effects of alternative taxes on cigarette prices. J Polit Econ 86(2):325–328

Keeler TE, The-wei H, Barnett PG, Manning WG, Sung H-Y (1996) Do cigarette producers price-discriminate by state? An empirical analysis of local cigarette pricing and taxation. J Health Econ 15(4):499–512

Lovenheim MF (2008) How far to the border? The extent and impact of cross-border cigarette sales. Natl Tax J 61(1):7–33

Maclean JC, Webber D, Sindelar JL (2013) The roles of assimilation and ethnic enclave residence in immigrant smoking. NBER Working Paper no. 19753

McCarthy WJ, Caskey NH, Jarvik ME (1991) Ethnic differences in nicotine exposure. Am J Public Health 82(8):1171–1172

Merriman D (2010) The micro-geography of tax avoidance: evidence from littered cigarette packs in Chicago. Am Econ J Econ Policy 2(2):61–84

Nevo A (2001) Measuring market power in the ready-to-eat cereal industry. Econometrica 69(2):307–342

Olshansky SJ et al (2012) Differences in life expectancy due to race and educational differences are widening, and many may not catch up. Health Affairs 31(8):1803–1813

Orzechowski W, Walker RC (2012) The tax burden on tobacco, vol 47. Orzechowski & Walker, Arlington, VA

Perez-Stable EJ, Herrera B, Jacob P, Benowitz NL (1998) Nicotine metabolism and intake in black and white smokers. J Am Med Assoc 280(2):152–156

Petrin A (2002) Quantifying the benefits of new products: the case of the minivan. J Polit Econ 110(4):705–729

Seade J (1985) Profitable cost increases and the shifting of taxation: equilibrium responses of markets in oligopoly. Working Paper, University of Warwick

Shelley D, Cantrell J, Moon-Howard J, Ramjohn DQ, VanDevanter N (2007) The \$5 man: the underground economic response to a large cigarette tax increase in New York city. Am J Public Health 97(8):1483–1488

Smith H (2004) Supermarket choice and supermarket competition in market equilibrium. Rev Econ Stud 71(1):235–263

Sobel RS, Garrett TA (1997) Taxation and product quality: new evidence from generic cigarettes. J Polit Econ 105(4):880–887

Stern N (1987) The effects of taxation, price control and government contracts in oligopoly and monopolistic competition. J Public Econ 32(2):133–158

Sullivan RS, Dutkowsky DH (2012) The effect of cigarette taxation on prices: an empirical analysis using local-level data. Public Finance Rev 40(6):687–711

Toomey TL, Chen V, Forester JL, Van Coevering P, Lenk KM (2009) Do cigarette prices vary by brand, neighborhood, and store characteristics? Public Health Rep 124(4):535–540

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank an anonymous reviewer, editor Subal C. Kumbhakar, Minsoo Park, seminar participants at Korea University and Sungkyunkwan University (SKKU), and participants at the 2016 meetings of the Korea International Economic Association for valuable comments and suggestions. This work was supported by the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Korea and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2017S1A5A2A02068347).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, H., Lee, D. Racial demographics and cigarette tax shifting: evidence from scanner data. Empir Econ 61, 1011–1037 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-020-01876-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-020-01876-6