Abstract

This paper focuses on empirical investigation of the J-curve phenomenon in the Czech economy. There are emphasized some problem areas of past research and suggested, from our point of view, better practices. The entire analysis is framed within the context of a small open economy. Using aggregate quarterly data for the period 2000–2014, we find that the real effective exchange rate has a strongly negative effect on trade balance in the short run; this effect is, however, replaced with a positive one in the long run, thus confirming the J-curve phenomenon. It follows from the computed impulse-response functions that a positive effect can occur as early as the second quarter. Alternatively, if depreciation or devaluation is perceived by economic agents as permanent, the improvement in the trade balance arrives with a time delay (ranging from 2 to 3 years). Besides domestic and foreign income, domestic and foreign interest rate were also chosen as explanatory variables with an intention to incorporate international borrowing and lending. It has been shown that the intertemporal substitution represents a marginal factor for the trade balance determination. Conversely, domestic economic growth exhibits a significantly greater influence.

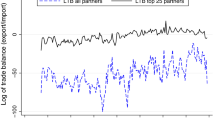

Source: Czech Statistical Office; own computations

Source: Czech Statistical Office; own computations

Source: Czech Statistical Office, Czech National Bank, Eurostat, Federal Reserve System

Source: Own computations

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Apart from the Czech Republic, the authors also study Cyprus, Hungary, Poland, Slovakia, Bulgaria, Croatia, Romania, Turkey, Russia and Ukraine.

Outside the Czech Republic, Hungary and Poland are considered as well. Albeit the authors present the results of aggregate study, much of their interest is devoted to the trade between the countries and Germany (their most important trading partner).

In the case of Sweden, it is possible to see that this obligation can be bypassed for a relatively long time.

Upon the symmetric currency pricing in international trade, the J-curve is even justifiable by the different rate of price stickiness in export and import prices. For the discussion of pricing in the international trade and its relationship to the J-curve phenomenon refer to Ahtiala (1983).

The simultaneity bias might be investigated deeply through the maximum-likelihood estimation of the whole system of equations. But, according to the recent results, the simultaneity does not pose a problem in this area of interest. The practices used by Rose and Yellen are discussed in Bahmani-Oskooee and Brooks (1999), who found an evidence for the same countries, at least for the long-run effect.

That view is clearly subjective, but it is a hard work to summarize objectively the results, for example through the meta-analysis (with a quantification of publication bias), mainly due to the diversity in methodologies.

Although we do not apply it, the band-pass filtering of estimated IR functions may partly reduce the impact of measurement errors.

This does not mean that the variables cannot be mutually Granger causal.

We restricted the deterministic trend just to the long-run relation.

The index expression is chosen because of its logarithmic tractability.

Under balance of incomes, we consider the difference between interests, profits and dividends (generally, income derived from the ownership of assets) received from abroad and those which are sent abroad. Balance of incomes thus forms a sub-balance of the current account of the balance of payments.

Balance of transfers is defined as the difference between unilateral receipts from abroad and unilateral payments sent abroad. Balance of transfers is also a sub-balance of the current account of the balance of payments.

We do not express the interest rates in logarithms, because we prefer to interpret their changes in percentage points, i.e., as simple differences rather than as growth rates.

The reverse applies to an increase in the domestic interest rate.

Computed from seasonally adjusted quarterly data.

Weight of the euro in the basket of currencies for calculating the real effective exchange rate is 68.4%.

Standard errors in parentheses.

Average inflation differential between the Czech and the euro area economy, i.e., \(\pi _{ t} - \pi _{ t}^{ *}\), computed as the quadratic mean of yearly inflation differentials based on quarterly data has been in reality during the observed period equal to 1.41 pp.

Measured by information criteria.

In derivation we only use the definition of steady state.

Upon the assumption about weak exogeneity or long-run forcing nature of effective exchange rate, both incomes and both interest rates.

\(\theta _{ 0}\) equals \(-c_0 / \pi _{ 1}\).

Pace of the Czech transition in the 90s and early 2000s was substantially different. While the 90s witnessed an extensively discontinuous development leading into parameter instability, the development in the early 2000s was rather continuous and gradual, characterized by qualitative improvements.

Simultaneously, it frequently leads into a decrease in the value of imports.

Because we have not expressed the interest rates in logs initially, we cannot interpret the estimated long-run multipliers as elasticities, as in other cases. Instead, we use usual formula for the elasticity computation \(\theta _{j} \, \bar{x}_j / \bar{y}\), where the bar over variable indicates a sample average.

In relation to this, it is necessary to emphasize that it is not possible to use (19) instead of (10) for computation of equilibrium errors. Relationship (19) is a deterministic one and therefore has no stochastic (error) element. The fact that residuals from regression (10) are in most cases serially correlated here only represents a natural property of equilibrium errors.

Under the condition that the original equilibrium remains unchanged, see the next.

The objection of Demirden and Pastine (1995) relates to feedback effects which may occur between regressand and regressors and thus invalidate the univariate approach. The authors do not deal with hysteresis.

With \(\mathbb {N}_{0}\) we denote the set of natural numbers extended by the number zero.

If we choose more than one x, then it is not possible to separate effects (impulses) of different regressors to regressand. The same reasoning also applies in the next case of the cumulative impulse-response function.

References

Ahtiala P (1983) A note on the J-curve. Scand J Econ 85(4):541–542

Bahmani-Oskooee M, Brooks TJ (1999) Bilateral J-curve between U.S. and her trading partners. Rev World Econ 135(1):156–165

Bahmani-Oskooee M, Goswami GG (2003) A disaggregated approach to test the J-curve phenomenon: Japan versus her major trading partners. J Econ Finance 27(1):102–113

Bahmani-Oskooee M, Goswami GG, Talukdar BK (2008) The bilateral J-curve: Canada versus her 20 trading partners. Int Rev Appl Econ 22(1):93–104

Bahmani-Oskooee M, Kutan AM (2009) The J-Curve in the emerging economies of Eastern Europe. Appl Econ 41(20):2523–2532

Bahmani-Oskooee M, Harvey H, Hegerty SW (2013) Empirical tests of the Marshall–Lerner condition: a literature review. J Econ Stud 40(3):411–443

Bahmani-Oskooee M, Fariditavana H (2016) Nonlinear ARDL approach and the J-Curve phenomenon. Open Econ Rev 27(1):51–70

Boyd D, Caporale GM, Smith R (2001) Real exchange rate effects on the balance of trade: cointegration and the Marshall–Lerner condition. Int J Finance Econ 6(3):187–200

Costamagna R (2014) Competitive devaluations and the trade balance in less developed countries: an empirical study of Latin American countries. Econ Anal Policy 44(3):266–278

Demirden T, Pastine I (1995) Flexible exchange rates and the J-curve: an alternative approach. Econ Lett 48(3–4):373–377

Engle RF, Granger CWJ (1987) Co-integration and error correction: representation, estimation, and testing. Econometrica 55(2):251–276

Fullerton TM, Sawyer WC, Sprinkle RL (1999) Latin American trade elasticities. J Econ Finance 23(2):143–156

Goldstein M, Khan MS (1985) Income and price effects in foreign trade. In: Jones RW, Kenen PB (eds) Handbook of international economics. North-Holland, Amsterdam

Hacker RS, Hatemi-J A (2003) Is the J-curve effect observable for small North European economies? Open Econ Rev 14(2):119–134

Hacker RS, Hatemi-J A (2004) The effect of exchange rate changes on trade balances in the short and long run: evidence from German trade with transitional Central European economies. Econ Transit 12(4):777–799

Houthakker HS, Magee SP (1969) Income and price elasticities in world trade. Rev Econ Stat 51(2):111–125

Johansen S (1988) Statistical analysis of cointegration vectors. J Econ Dyn Control 12(2–3):231–254

Johansen S (1991) Estimation and hypothesis testing of cointegration vectors in Gaussian vector autoregressive models. Econometrica 59(6):1551–1580

Johnson H (1958) International trade and economic growth. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Junz HB, Rhomberg RR (1973) Price competitiveness in export trade among industrial countries. Am Econ Rev 63(2):412–418

Ketenci N, Uz I (2011) Bilateral and regional trade elasticities of the EU. Empir Econ 40(3):839–854

Khan MS (1974) Import and export demand in developing countries. Staff Papers–Int Monet Fund 21(3):678–693

Lal AK, Lowinger TC (2002) Nominal effective exchange rate and trade balance adjustment in South Asia countries. J Asian Econ 13(3):371–383

Lerner A (1944) The economics of control. Macmillan, London

Machlup F (1939) The theory of foreign exchanges. Economica 6(24):375–397

Magee SP (1973) Currency contracts, pass-through, and devaluation. Brook Papers Econ Act 4(1):303–325

Marshall A (1923) Money, credit, and commerce. Macmillan, London

Obstfeld M, Rogoff K (1996) Foundations of international macroeconomics. The MIT Press, Cambridge

Orcutt GH (1950) Measurement of price elasticities in international trade. Rev Econ Stat 32(2):117–132

Pesaran MH, Shin Y, Smith RJ (2001) Bounds testing approaches to the analysis of level relationships. J Appl Econ 16(3):289–326

Robinson J (1937) Essays in the theory of employment. Basil Blackwell, Oxford

Rose AK, Yellen JL (1989) Is there a J-curve? J Monet Econ 24(1):53–68

Rose AK (1991) The role of exchange rates in a popular model of international trade. Does the “Marshall–Lerner” condition hold? J Int Econ 30(3–4):301–316

Sawyer WC, Sprinkle RL (1996) The demand for imports and exports in the U.S.: a survey. J Econ Finance 20(1):147–178

Sawyer WC, Sprinkle RL (1997) The demand for imports and exports in Japan: a survey. J Jpn Int Econ 11(2):247–259

Stern RM, Francis J, Schumacher B (1976) Price elasticities in international trade: an annotated bibliography. Macmillan, London

Wang CH, Lin CHA, Yang CH (2012) Short-run and long-run effects of exchange rate change on trade balance: evidence from China and its trading partners. Jpn World Econ 24(4):266–273

Warner D, Kreinin ME (1983) Determinants of international trade flows. Rev Econ Stat 65(1):96–104

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

The author is grateful for the financial support of the project “Efficiency of Channels in Monetary Transmission” (No. 20141034), under which this study was elaborated, from the Internal Grant Agency of the Faculty of Economics and Management, Czech University of Life Sciences Prague.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gürtler, M. Dynamic analysis of trade balance behavior in a small open economy: the J-curve phenomenon and the Czech economy. Empir Econ 56, 469–497 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-018-1445-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-018-1445-4

Keywords

- J-curve

- Trade balance

- Exchange rate

- Structural approach to cointegration

- Impulse-response analysis

- Hysteresis

- Small open economy