Abstract

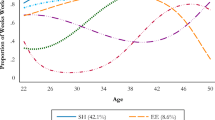

Has the early career become less stable during the 1980s and 1990s? And does a lack of early-career employment stability inhibit wage growth? I analyze exceptionally rich administrative data on male graduates from Germany’s dual education system to shed more light on these important questions. The data indicate a decline in youth employment durations since the late 1970s, limited to already relatively short durations. Controlling for endogeneity of employment in youth with training firm fixed effects and by exploiting institutional variation in the timing of nationwide macroeconomic shocks, I find significant returns to early-career employment stability in terms of higher wages in adulthood. These returns decline not only across the wage distribution, but also with cohort age. The findings suggest less stable employment in the early years of a career to have become increasingly costly during the 1990s for the least advantaged workers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Closely related is the literature on so-called scarring effects of youth unemployment. Early work for the USA by Heckman and Borjas (1980), Ellwood (1982), or Corcoran and Hill (1985) finds little evidence for youth unemployment having long-lasting negative effects on career development. More recent studies broadly confirm a negative persistent impact of youth unemployment on future career outcomes in European data, see Arulampalam (2001), Gregg (2001), Gregg and Tominey (2005), Möller and Umkehrer (2015), Schmillen and Umkehrer (2017), among others, and Ryan (2001) for an overview.

This system combines occupation-specific practical training at a firm with learning in part-time schools.

To make sure that results are not confounded by persistent differences in the quality of initial jobs, I restrict the sample to workers who have changed their employer after the end of the early career stage in a sensitivity check. As emphasized by Neumark (2002), this restriction disables a possible direct connection between persistent match quality and adult outcomes. I also follow Gregg (2001) and directly control for the overall economic environment prevailing in adulthood to account for autocorrelation in aggregate labor market conditions. Reassuringly, the results are robust.

Note that this approach does not involve any unemployment variation neither between nor within regions. Instead, I link each apprentice’s calendar day of graduation to daily national unemployment rates averaged over the early career period. The construction of daily unemployment rates is possible for the full population in the administrative data because both employment and unemployment spells are recorded exact to the day.

Part of the decline in early-career employment stability might be driven by changes in the composition of apprentices over time. However, Rhein and Stüber (2014) show that the length of employment relationships has been reduced between 1975 and 2009 among the general West German workforce, too. Declining employment stability therefore cannot be solely explained by changes in the selection into apprenticeship training over time. Furthermore, compositional changes have been found to account for very little of observed changes in employment patterns more generally, cf. Kroft et al. (2016).

Throughout the paper, I show that the results hold for a variety of different measures of both youth employment and adult wage, and that findings do not qualitatively differ across different econometric models either.

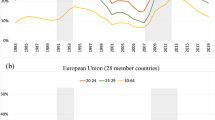

In the early 1990s, about 65% of the German resident population aged between 16 and 24 concluded a new training contract in the dual education system. This fraction dropped to around 60% during the early 2000s. Until 2009, however, the participation rate in the dual system again slightly increased to 61.9%, see Gericke et al. (2011) for further details.

In this study, I define years of potential labor market experience (in short: experience years) as starting on the first day after the last day of apprenticeship training. For instance, assume an apprentice’s training period ends on August 31 of a given year; then, the first experience year starts September 1 of the same year and ends August 31 the next year. As the actual day on which the training period ends is observable in the data I do not have to estimate potential experience as a function of education and age.

I exclude the first year of potential experience in the baseline scenario because periods of initial job searching or military service might blur the picture of stability.

Potential reasons for the asymmetric decline in early-career employment stability comprise alternative forms of employment, like fixed-term contracts or involuntary part-time, gaining in importance, cf., e.g., Levenson (2000) or Rhein and Stüber (2014), respectively, technological progress increasing the substitutability of certain tasks with capital and enhancing the demand for specific skills that are complementary to capital, cf. Autor et al. (2003), Spitz-Oener (2006), Acemoglu and Autor (2011) among others, rising incentives for educational investment inducing shifts toward higher educational attainment, cf., e.g., Altonji et al. (2012), growing internationalization complicating the formation of stable and productive employer–employee matches, cf. Abraham and Taylor (1996), Dube and Kaplan (2010), Smith (2012), or Card et al. (2013), and strict employment protection legislation prolonging the duration of both employment and unemployment by reducing employment terminations, and hampering job creation, cf. OECD (1999) or Pissarides (2001). However, the focus of this paper is on the longer-term career effects of experiencing an unstable early employment career. An analysis of the different mechanisms underlying declining employment stability is left to future work.

Further explanations include lowering of reservation wages during joblessness, the presence of career ladders, implicit contracting, labor unions, hiring and firing costs, discouragement or habituation effects, lack of physical capital after recessions, or different bargaining powers of insiders and outsiders, see, e.g., von Wachter and Bender (2006) or Schmillen and Umkehrer (2017) for further references.

Table 5 in Appendix uses BHP data to describe the selection process of firms into the dual education system as well as its evolution over time. Firms providing training are positively selected. They are larger and pay higher wages, on average, and these differences increase over time. Most training firms operate in the manufacturing and the service/commercial sectors, whereby the latter sectors gain in relative importance over time, while the manufacturing sector looses shares. In the short-run, the composition of firms providing training is basically stable. Therefore, controlling for changes in the composition of training firms is primarily important when conducting longer time comparisons between graduation periods, while compositional changes should play far less of a role for analyses within graduation periods.

By exploiting solely variation in early-career employment stability between graduates of the same training firm and the same cohort, the inclusion of fixed effects for the training firm and the graduation cohort accounts for any sorting into training firms and training firm composition effects based on time-invariant unobserved firm characteristics. Additional controls for time-varying firm characteristics account for the observable part of the sorting process due to those time-varying characteristics. Of course, one can never be completely sure that this strategy is capable of controlling for the full initial sorting process. However, as will be shown in Sect. 5.1, estimates accounting only for fixed effects do not differ much from estimates adding time-varying controls. Therefore, I feel confident that the process of initial sorting is sufficiently controlled for via this strategy in the current application.

A more fundamental form of bias arises from the fact that wages are not observable for every worker in every year. In the present case of male apprenticeship graduates, sorting in unemployment should be the main reason for not observing a wage. As shown below, the returns to early-career employment stability are particularly pronounced at the bottom of the wage distribution. As the unemployed can plausibly be expected to be overrepresented among workers with the lowest earning potential, sample selection should lead to a downward bias in estimates of the returns to stability, i.e., the estimates of the returns derived from the selected sample are likely to represent a lower-bound estimate of the true returns.

Unfortunately, in the IEB it is not obvious why a training period actually ends. Apprenticeship contracts might for instance be terminated due to dropping out prematurely or by ultimately failing in the finals. It is also not possible to observe if a graduate had to repeat an exam, which he could usually do within the course of 1 year. However, both dropouts and exam failures are quite rare in the sample under study. According to data of the Federal Institute for Vocational Education and Training (2014), between 1993 and 2012 an average of merely 8% of training contracts of West German males were terminated prematurely. 82.1% of these terminations occurred within the first two training years. The basic sample restriction to 2 years or more but no more than 4 years of training therefore already rules out the vast majority of dropouts. Furthermore, with 94.6% almost all apprentices reaching the finals graduate successfully, and 90% of them do so at the first try, see Federal Ministry of Education and Research (2003). Consequently, the results are representative for males successfully graduating from the dual education system in West Germany.

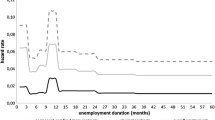

Specifically, the calculation of the unemployment measure is carried out as follows: First, the aggregate unemployment rate, \(\mathrm{UR}_{d}\) (in percent), prevailing on calendar day d is calculated using a 2% random sample of labor market biographies from the IEB. Because the IEB do not cover periods of official job searching before the year 2000, unemployment is identified via the receipt of unemployment benefits. However, more than 90% of workers who are registered as unemployed are eligible to receive unemployment benefits. Next, moving averages over the following \(x=365\) days are calculated as \(\mathrm{UR}_{e,p} = \frac{1}{x} \sum _{t=d+xp-x}^{d+xp-1}\mathrm{UR}_{t}\). Merged by the first day of each year of potential experience, \(\mathrm{UR}_{e,p}\) varies with the year of potential experience p and an individual’s day of labor market entry e. Finally, averaging over the individual’s early career y yields \(\mathrm{UR}_{e,y}=\frac{1}{4} \sum _{p=2}^{5}\mathrm{UR}_{e,p}\). The two steps of averaging are necessary for two reasons: first, to create one single variable reflecting the overall economic environment prevailing during the early career; second, to account for the pronounced seasonal pattern in the daily unemployment rate shown in Fig. 2. This pattern arises because jobs are particularly often separated at the end and particularly often started at the beginning of a week, month, or year.

Systematically dropping out of training or voluntarily repeating the final examinations is unlikely to significantly bias the IV estimates for at least two reasons: First, as outlined in footnote 16, such cases are quite rare in the sample under study. Second, bias would arise only if the omitted factors are correlated with the aggregate unemployment rate faced during the early career. On the one hand, I control for cohort effects. On the other hand, it appears not very plausible that apprentices adjust their behavior in anticipation of a recession that has not even started yet and, for instance, deliberately fail only to graduate half a year later. Reassuringly, the data show no increase in training durations over the graduation periods.

Due to peculiarities of the reporting system, before 1991 a considerable proportion of employers reported December 31 as the day of graduation. This poses a problem for the validity of the identification strategy if such “delayed reports” occur systematically. As dropping these cases could in turn induce sample selection bias, I prefer to account for delayed reporting by including a dummy as additional control variable.

The findings also do not depend on a particular measure of employment or wages, respectively. Table 7 in Appendix shows that the results are robust to using measures of job stability, occupational stability, and employment continuity instead of employment stability, to measuring employment stability over the first five experience years, to adding periods of part-time employment, or to relaxing the linearity assumption by including a cubic polynomial in early-career employment stability. Regressions presented in Table 8 in Appendix proof further robustness to measuring the adult wage not only from full-time but also from part-time employment, to averaging wages over experience years seven to nine, and to excluding the roughly 4% of workers employed by East German firms at least once during the observation period. Finally, I also tested if the IV exclusion restriction is violated by persistent differences in the quality of job matches which could be induced by the instrument. As can be seen from column (8) of Table 7, the IV results for the youngest cohorts are robust to reducing the sample to workers who have changed their employer after the end of the early career stage. This robustness suggests that the TSLS estimates are not subject to persistent differences in the quality of initial jobs which might be induced by the instrument, cf. Neumark (2002). Unfortunately, the same test did not generate meaningful results in the case of the older cohorts because of a lack of precision resulting from the large number of delayed reports mentioned in footnote 19.

This IVQR procedure allows the instrumentation of a continuous endogenous regressor in a quantile regression framework. Under the conditions stated in Chernozhukov and Hansen (2005), a quantile treatment effect is identified without it being necessary to rely on functional form assumptions. The procedure is implemented on the basis of the MATLAB command inv_qr.

References

Abowd JM, Kramarz F, Margolis DN (1999) Why do firms train? Theory and evidence. Econometrica 62:161–178

Abraham K, Taylor S (1996) Firms’ use of outside contractors: theory and evidence. JOLE 14:394–424

Acemoglu D (1995) Public policy in a model of long-term unemployment. Economica 67:251–333

Acemoglu D, Autor D (2011) Skills, tasks and technologies: implications for employment and earnings. In: Ashenfelter O, Card D (eds) Handbook of labor economics, vol IV. Elsevier, London, pp 1043–1171 Part B

Adda J, Dustmann C, Meghir C, Robin J-M (2013) Career progression, economic downturns, and skills. NBER working paper 18832

Altonji JG, Bharadwaj P, Lange F (2012) Changes in the characteristics of American youth: implications for adult outcomes. JOLE 30:783–828

Angrist J, Imbens G, Rubin D (1996) Identification of causal effects using instrumental variables. JASA 91:444–455

Antonczyk D, Fitzenberger B, Sommerfeld K (2010) Rising wage inequality, the decline of collective bargaining, and the gender wage gap. Labour Econ 30:835–847

Atkinson J (1996) Employers, recruitment and the unemployed, Institute for Employment Studies Report 325. Grantham Book Services, Grantham

Autor DH (2009) Introduction to studies of labor market intermediation. In: Autor D (ed) Studies in labor market intermediation. University of Chicago Press, Elsevier, New York

Autor DH, Levy F, Murnane RJ (2003) The skill content of recent technological change: an empirical exploration. QJE 118:1279–1333

Arulampalam W (2001) Is unemployment really scarring? Effects of unemployment experiences on wages. EJ 111:585–606

Bartel A, Borjas G (1981) Wage growth and job turnover. In: Sherwin R (ed) Studies in labor markets 65–90. University of Chicago Press, Elsevier, Chicago

Ben-Porath Y (1967) The production of human capital and the life cycle of earnings. JPE 75:352–365

Bergmann A, Mertens A (2011) Job stability trends, lay-offs, and transitions to unemployment in West Germany. LABOUR 25:421–446

Bernhardt A, Morris M, Handcock MS, Scott MA (1999) Trends in job instability and wages for young adult men. JOLE 17:65–90

Blanchard OJ, Diamond PA (1994) Ranking, unemployment duration, and wages. REStud 61:417–434

Blanchflower DG, Oswald AJ (1994) The wage curve. MIT Press, Cambridge

Card D, Heining J, Kline P (2013) Workplace heterogeneity and the rise of West German wage inequality. QJE 128:967–1015

Chernozhukov V, Hansen C (2005) An IV model of quantile treatment effects. Econometrica 73:245–261

Chernozhukov V, Hansen C (2008) Instrumental variable quantile regression: a robust inference approach. J Econom 142:379–398

Corcoran M, Hill M (1985) Reoccurrence of unemployment among adult men. JHR 20:165–183

Deutsche Bundesbank (2012) Time series BBK01.UJFB99: Consumer price index, retrieved in February 2012, Deutsche Bundesbank, Frankfurt am Main. http://www.bundesbank.de

Dube A, Kaplan E (2010) Does outsourcing reduce wages in the low-wage service occupations? Evidence from Janitors and Guards. ILR Rev 63:287–306

Dustmann C, Ludsteck J, Schönberg U (2009) Revisiting the German wage structure. QJE 124:843–881

Ellwood D (1982) Teenage unemployment: permanent scars or temporary blemishes. In: Freeman R, Wise D (eds) The youth labor market problem: its nature, causes, and consequences. NBER Books, Cambridge

European Union (2013) Council recommendation of 22 April 2013 on establishing a Youth Guarantee. Official Journal of the European Union C 120/01

Federal Institute for Vocational Education and Training (2014) Time series: all training occupations, West Germany, retrieved in July 2014, BIBB, Bonn. http://www.bibb.de/dazubi

Federal Ministry of Education and Research (2003) Berufsausbildung sichtbar gemacht—Grundelemente des dualen Systems. BMBF Publik, 4.Auflage, Bonn

Firpo S, Fortin NM, Lemieux T (2009) Unconditional quantile regressions. QJE 124:953–973

Fortin N, Lemieux T, Firpo S (2011) Decomposition methods in economics. In: Ashenfelter O, Card D (eds) Handbook of labor economics, vol IV. Elsevier, New York, pp 1–102 Part A

Franz W, Zimmermann V (2002) The transition from apprenticeship training to work. Int J Manpow 23:411–425

Gardecki R, Neumark D (1998) Order from Chaos? The effects of early labor market experiences on adult labor market outcomes. ILR Rev 51:299–322

Gericke N, Uhly A, Ulrich JG (2011) Wie hoch ist die Quote der Jugendlichen, die eine duale Berufsausbildung aufnehmen? Indikatoren zur Bildungsbeteiligung. Berufsbildung in Wissenschaft und Praxis 1:41–43

Gibbons R, Katz L (1991) Layoffs and lemons. JOLE 9:351–380

Gregg P (2001) The impact of youth unemployment on adult unemployment in the NCDS. EJ 109:626–653

Gregg P, Tominey E (2005) The wage scar from male youth unemployment. Labour Econ 12:487–509

Gruhl A, Schmucker A, Seth S (2012) The establishment history panel 1975–2010 FDZ Datenreport 04/2012

Harhoff D, Kane TJ (1997) Is the German apprenticeship system a panacea for the U.S. labor market? J Popul Econ 10:171–196

Heckman J, Borjas G (1980) Does unemployment cause future unemployment? Definitions, questions and answers from a continuous time model of heterogeneity and state dependence. Economica 47:247–283

Hippach-Schneider U, Krause M, Woll C (2007) Vocational education and training in Germany: short description. European Centre for the Development of Vocational Training, Thessaloniki

Jann B (2008) The BlinderOaxaca decomposition for linear regression models. Stata J 8:453–479

Koenker R, Bassett G (1978) Regression quantiles. Econometrica 46:33–50

Kroft K, Lange F, Notowidigdo M (2013) Duration dependence and labor market conditions: theory and evidence from a field experiment. QJE 128:1123–1167

Kroft K, Lange F, Notowidigdo MJ, Katz LF (2016) Long-term unemployment and the great recession: the role of composition, duration dependence, and nonparticipation. JOLE 34:S7–S54

Levenson AR (2000) Long-run trends in part-time and temporary employment: toward an understanding. In: Neumark D (ed) On the job-is long-term employment a thing of the past? Chapter 10 335–397. Russell Sage Foundation, New York

Mincer J (1962) On-the-job training: costs, returns, and some implications. JPE 70:50–79

Möller J, Umkehrer M (2015) Are there long-term earnings scars from youth unemployment in Germany? JBNST 235:474–498

Monks J, Pizer S (1998) Trends in voluntary and involuntary turnover. Ind Relat 37:440–459

Neumark D (2000) On the job-is long-term employment a thing of the past?. Russell Sage Foundation, New York

Neumark D (2002) Youth labor markets in the United States: shopping around vs staying put. REStat 84:462–482

Oberschachtsiek D, Scioch P, Seysen C, Heining J (2009) Integrated employment biographies sample IEBS: handbook for the IEBS in the 2008 version. FDZ Datenreport 03/2009

OECD Employment Outlook (1999) Employment protection and labour market performance, Chapter 2. OECD, Paris

Oreopoulos P, von Wachter T, Heisz A (2012) The short- and long-term career effects of graduating in a recession. AEJ Appl Econ 4:1–29

Pissarides CA (1992) Loss of skill during unemployment and the persistence of employment shocks. QJE 107:1371–1391

Pissarides CA (2001) Employment protection. QJE 8:131–159

Rhein T, Stüber H (2014) Beschäftigungsdauer im Zeitvergleich: Bei Jüngeren ist die Stabilität der Beschäftigung gesunken. IAB Kurzbericht 03/2014

Ryan P (2001) The school-to-work transition: a cross-national perspective. JEL 39:34–92

Schmillen A, Umkehrer M (2017) The scars of youth—effects of early-career unemployment on future unemployment experience. Int Labour Rev 156:465–494

Smith CL (2012) The impact of low-skilled immigration on the youth labor market. JOLE 30:55–89

Spence M (1973) Job market signaling. QJE 87:355–374

Spitz-Oener A (2006) Technical change, job tasks, and rising educational demands: looking outside the wage structure. JOLE 24:235–270

Stock J, Wright J, Yogo M (2002) A survey of weak instruments and weak identification in generalized method of moments. J Bus Econ Stat 20:518–529

Stuart J (2002) Recent trends in job stability and job security: evidence from the March CPS. Bureau of Labor Statistics Working Paper 356

Topel R, Ward M (1992) Job mobility and the careers of young men. QJE 107:439–479

Vishwanath T (1989) Job search, stigma effect, and escape rate from unemployment. JOLE 7:487–502

von Wachter T, Bender S (2006) In the right place at the wrong time: the role of firms and luck in young workers’ careers. AER 96:1679–1705

Winkelmann R (1996) Employment prospects and skill acquisition of apprenticeship-trained workers in Germany. ILR Rev 49:658–672

Wooldridge J (1995) Score diagnostics for linear models estimated by two stage least squares. In: Maddala G, Phillips P, Srinivasan T (eds) Advances in econometrics and quantitative economics: essays in honor of professor C. R. Rao. Blackwell, Oxford, pp 66–87

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Stefan Bender, Philipp vom Berge, Mario Bossler, Bernd Fitzenberger, Joachim Möller, Dana Müller, Achim Schmillen, Till von Wachter, referees, editors, and participants at seminars and conferences for helpful comments and suggestions. The usual disclaimer applies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Umkehrer, M. The impact of declining youth employment stability on future wages. Empir Econ 56, 619–650 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-018-1444-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-018-1444-5