Abstract

While rising unemployment generally reduces people’s happiness, researchers argue that there is a compensating social-norm effect for the unemployed individual, who might suffer less when it is more common to be unemployed. This empirical study rejects this thesis for German panel data, however, and finds that individual unemployment is even more hurtful when regional unemployment is higher. On the other hand, an extended model that separately considers individuals who feel stigmatised from living off public funds yields strong evidence that this group of people does in fact suffer less when the normative pressure to earn one’s own living is lower. A comprehensive discussion reconciles these findings with the existing research and concludes that to find evidence for the often described social-norm effect it is worthwhile to analyse disutility associated with benefit receipts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

For general surveys in happiness research, see, e.g., Frey and Stutzer (2002, 2005), Frey (2008) and Van Praag and Ferrer-i-Carbonell (2008). Studies specifically investigating the disutility effects of individual unemployment include those of Clark and Oswald (1994), Winkelmann and Winkelmann (1998), Carroll (2007), Chadi (2010) and Knabe and Rätzel (2011).

While Clark (2003) also examines the role of unemployment among other reference groups, namely, unemployment at the partner and household levels, the discussion in this study focuses only on the relationship between individual unemployment and others’ unemployment at the regional level.

Note that, for reasons of simplicity, and in accordance with the original definition of the social norm, the term “living off other people” is used throughout the paper despite its negative connotations.

As can be seen in Table 2, the division of Germany into regions in this study differs (slightly) from the official classification of the German federal states. Note that, in contrast to the SOEP data, the available unemployment data are not reported separately for East and West Berlin. On the other hand, the federal states of Rhineland-Palatinate and Saarland are not reported separately by the SOEP.

To be precise, the law defines persons as either directly eligible or as part of a “Bedarfsgemeinschaft”, which, in order to reduce complexity, is treated here as a regular household.

Note that the model considers the above assumption of no migration between regions.

Recall that higher levels of norm strength are expressed in smaller values in Table 2.

Note that Bavaria is associated with very strong norms (see Table 2), whereas NRW appears to be average in regard to unemployment and norms.

This is also confirmed by additional regressions on the basis of data from the same period of time (1984–2006) as in the Clark et al. studies. Using the same methods and controls, their “social norm of unemployment”-effect (found only for men) disappears as soon as the data is restricted to the western German regions.

Note that the geometric mean makes more sense compared to the arithmetic mean, since the latter would give more weight to outliers with large values. According to some additional regressions, the outcomes are nevertheless quite similar in both cases, so that the main findings are not affected by this aspect anyway.

Thanks to the de-meaning of norm strength levels and unemployment rates, the coefficient for each group can be interpreted as a mean effect for inhabitants of regions with average unemployment and average normative pressure. Hence, in line with the literature, the OLS outcomes indicate the unemployment-induced disutility to be about 0.5 points on the life satisfaction scale, and benefit receipts on average slightly more than 0.1 points.

The full collection of norm measures obtained from five different social surveys and each correlation matrix showing conformity with the SOEP-based measures in Table 2 are available from the author upon request.

Note that, following the insights from above, these alternative estimations with social-beliefs proxies are carried out without additional interactions concerning the East-West disparity.

This can be observed when comparing the third (EB03) and the fourth measure (EB04) in Table 10 The idea behind these two measures is that the more interviewees consider disadvantaged people to be lazy, the stronger the normative pressure to not live on public funds. However, there is not even a truly significant correlation between these two “laziness” variables, so varying outcomes in the regression analysis are no surprise.

Apart from this aspect, the more technical idea behind starting with data from 1999 is a change in how the household questionnaires ask interviewees about benefit receipts.

Note that the average unemployment rate here is 11.32%.

References

Ai C, Norton EC (2003) Interaction terms in logit and probit models. Econ Lett 80:123–129

Alesina A, Fuchs-Schündeln N (2007) Good-bye Lenin (or not?): the effect of communism on people’s preferences. Am Econ Rev 97:1507–1528

Alm J, Torgler B (2006) Culture differences and tax morale in the United States and in Europe. J Econ Psychol 27:224–246

Bruckmeier K, Wiemers J (2012) A new targeting: a new take-up? Non-take-up of social assistance in Germany after social policy reforms. Empir Econ 43:565–580

Carroll N (2007) Unemployment and psychological well-being. Econ Rec 83:287–302

Chadi A (2010) How to distinguish voluntary from involuntary unemployment: on the relationship between willingness to work and unemployment-induced unhappiness. Kyklos 63:317–329

Chadi A (2012) Employed but still unhappy? On the relevance of the social work norm. J Appl Soc Sci Stud (Schmollers Jahrbuch) 132:1–26

Clark AE (2003) Unemployment as a social norm: psychological evidence from panel data. J Labor Econ 21:323–351

Clark AE, Oswald AJ (1994) Unhappiness and unemployment. Econ J 104:648–659

Clark AE, Knabe A, Rätzel S (2009) Unemployment as a social norm in Germany. J Appl Soc Sci Stud (Schmollers Jahrbuch) 129:251–260

Clark AE, Knabe A, Rätzel S (2010) Boon or bane? Others’ unemployment, well-being and job insecurity. Labour Econ 17:52–61

De Neve JE, Christakis NA, Fowler JA, Frey BS (2012) Genes, economics, and happiness. J Neurosci Psychol Econ 5:193–211

Di Tella R, MacCulloch RJ, Oswald AJ (2001) Preferences over inflation and unemployment: evidence from surveys of happiness. Am Econ Rev 91:335–341

Di Tella R, MacCulloch RJ, Oswald AJ (2003) The macroeconomics of happiness. Rev Econ Stat 85:809–827

Elster J (1989a) Social norms and economic theory. J Econ Perspect 3:99–117

Elster J (1989b) The cement of society. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Ferrer-i-Carbonell A, Frijters P (2004) How important is methodology for the estimates of the determinants of happiness? Econ J 114:641–659

Frey BS (2008) Happiness: a revolution in economics. MIT Press, Cambridge

Frey BS, Stutzer A (2002) Happiness and economics: how the economy and institutions affect well-being. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Frey BS, Stutzer A (2005) Happiness research: state and prospects. Rev Soc Econ 62:207–228

Frijters P, Haisken-DeNew JP, Shields MA (2004) Money does matter! Evidence from increasing real income and life satisfaction in East Germany following reunification. Am Econ Rev 94:730–740

Heinemann F (2008) Is the welfare state self-destructive? A study of government benefit morale. Kyklos 61:237–257

Kassenboehmer S, Haisken-DeNew JP (2009) Social jealousy and stigma: negative externalities of social assistance payments in Germany. Ruhr economics papers no. 117, Department of Economics, University of Bochum, Bochum

Knabe A, Rätzel S (2011) Scarring or scaring? The psychological impact of past unemployment and future unemployment risk. Economica 78:283–293

Lindbeck A (1995) Welfare state disincentives with endogenous habits and norms. Scand J Econ 97:477–494

Lindbeck A, Nyberg S (2006) Raising children to work hard: altruism, work norms, and social insurance. Q J Econ 121:1473–1503

Luechinger S, Meier S, Stutzer A (2010) Why does unemployment hurt the employed? Evidence from the life satisfaction gap between the public and the private sector. J Hum Res 45:998–1045

Lykken D, Tellegen A (1996) Happiness is a stochastic phenomenon. Psychol Sci 7:186–189

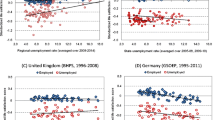

Oesch D, Lipps O (forthcoming) Does unemployment hurt less if there is more of it around? A panel data analysis for Germany and Switzerland. Eur Sociol Rev

Powdthavee N (2007) Are there geographical variations in the psychological cost of unemployment in South Africa? Soc Indic Res 80:629–652

Shields MA, Wheatley Price S (2005) Exploring the economics and social determinants of psychological well-being and perceived social support in England. J R Stat Soc A 168:513–537

Shields MA, Wheatley Price S, Wooden M (2009) Life satisfaction and the economic and social characteristics of neighbourhoods. J Popul Econ 22:421–443

Stavrova O, Schlosser T, Fetchenhauer D (2011) Are the unemployed equally unhappy all around the world? The role of the social norms to work and welfare state provision in 28 OECD countries. J Econ Psychol 32:159–171

Stutzer A, Lalive R (2004) The role of social work norms in job searching and subjective well-being. J Eur Econ Assoc 2:696–719

Torgler B (2005) A knight without a sword? The effects of audit courts on tax morale. J Inst Theor Econ 161:735–760

Van Praag BMS, Ferrer-i-Carbonell A (2008) Happiness quantified: a satisfaction calculus approach (revised edn). Oxford University Press, Oxford

Wagner G, Frick J, Schupp J (2007) The German socio-economic panel study (SOEP): scope, evolution and enhancements. J Appl Soc Sci Stud (Schmollers Jahrbuch) 127:139–169

Winkelmann L, Winkelmann R (1998) Why are the unemployed so unhappy? Economica 65:1–15

Young HP (2008) Social norms: the new Palgrave dictionary of economics. Macmillan, London

Acknowledgments

The author is grateful to Daniel Arnold, Tobias Böhm, Daniel Chen, Clemens Hetschko, Andreas Knabe, Tobias Pfaff, Ronnie Schöb, Mark Trede, Ulrich van Suntum, the anonymous referees as well as the participants of the 7th International SOEP Symposium, the HEIRs conference on markets and happiness and seminars at the University of Muenster for valuable comments and advice.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chadi, A. Regional unemployment and norm-induced effects on life satisfaction. Empir Econ 46, 1111–1141 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-013-0712-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-013-0712-7

Keywords

- Social norms

- Regional unemployment

- Individual unemployment

- Well-being

- Social benefits

- Labour market policies