Abstract

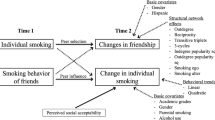

Adolescent smoking is one of the most pressing public health problems. The objective of this paper is to analyse the influence of peer pressure on adolescent cigarette consumption. More concretely, we explore the significance and robustness of the peer effects using several estimation methods employed in the existing literature. On the basis of the data provided by the 2004 Spanish survey on drug use in the school population, we estimate the probability of being a smoker by two-stage models. The results reveal that when we use standard errors used in the literature the class peer variable appears to be significant. However, the class peer variable is not significant when we calculate more exigent standard errors, a result that is robust across all specifications. The paper suggests the need for a more cautious interpretation of the peer effects found previously in the literature until a deeper analysis confirms the robustness of the peer effects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

As Krauth (2007) pointed out, in most cases it is only possible to distinguish between endogenous and contextual effects by assuming that one or the other is absent. Thus, as Lundborg (2006) pointed out, using measures of peer effects at the class-level, the importance of the contextual effects will be reduced, since when the reference group is broader, pupils are likely less exposed to the family background of their peers, and thus the observed peer effects are more likely to be caused by endogenous rather than contextual effects.

Thus, the final sample size is 10,666 individuals, of which 10,102 can be used in our estimations. According to our data set, first smoking decisions are mostly taken by Spanish adolescents before age 16. Specifically, 23.13 % of respondents aged 15 are smokers. Although it is difficult to generalize the results of the paper to broader age groups, we feel we are justified in doing so, since (i) this figure of 23.13 % of smokers among people who are 15 years old is a significant proportion of future smokers (37 % male, 28 % female according to the 2008 WHO report), (ii) the fact that we are using a large sample with more than 10,000 students, and (iii) the fact that the estimated marginal peer effects (0.558) are in the normal range found in the literature. Nevertheless, a caution must be introduced regarding the different gender composition of the adolescent and adult populations.

The first-stage estimates are available upon request.

In order to check the stability and, therefore, the robustness of these results, we estimate a linear probability model with the same three versions of the standard errors used in the Probit models. Once again, our results provide evidence that the peer effect is not robust when more restrictive standard errors, accounting for the cluster nature of the data, are considered. It should be noted that this conclusion is robust to several specifications, that is to say, in the linear probability model and in the Probit model with two estimation approaches. The estimates of the linear probability model are available upon request.

References

Ali M, Dwyer D (2009) Estimating peer effects in adolescent smoking behaviour: a longitudinal analysis. J Adolesc Health 45:402–408

Arellano M (2008) Binary models with endogenous explanatory variables. http://www.cemfi.es/~arellano/binary-endogeneity.pdf. Accessed 16 Jan 2012

Band PR, Le ND, Fang R, Deschamps M (2002) Carcinogenic and endocrine disrupting effects of cigarette smoke and the risk of breast cancer. Lancet 360:1044–1049

Becker GS, Murphy KM (1988) A theory of rational addiction. J Polit Econ 96:675–700

Becker GS, Grossman M, Murphy KM (1994) An empirical analysis of cigarette addiction. Am Econ Rev 84:396–418

Cameron AC, Trivedi PK (2005) Microeconometrics: methods and applications. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Case AC, Kartz LF (1991) The company you keep: the effects of family and neighbourhood on disadvantaged youths. NBER Working Paper No. 3705

Chaloupka F (1991) Rational addictive behavior and cigarette smoking. J Polit Econ 99:722–742

Clark AE, Lohéac Y (2007) It wasn’t me, it was them! Social influence in risky behaviour by adolescents. J Health Econ 26:763–784

Dekovic M, Wissink IB, Meijer AM (2004) The role of family and peer relations in adolescent antisocial behaviour: comparison of four ethnic groups. J Adolesc 27:497–514

Duarte R, Escario J, Molina J (2011) Peer effects, unobserved factors and risk behaviours in adolescence. Rev Econ Apl 55:125–151

Efron B, Tibshirani RJ (1993) An introduction to the bootstrap. Chapman and Hall, London

Eisenberg ME, Foster JL (2003) Adolescent smoking behaviour: measures of social norms. Am J Prev Med 25:122–128

Epple D, Romano RE (2011) Peer effects in education: a survey of the theory and evidence. In: Benhabib J, Bisin A, Jackson M (eds) Handbook of social economics, vol 1. Elsevier Sciencie, North Holland, pp 1053–1163

Escario JJ, Molina JA (2004) Will a special tax on tobacco reduce lung cancer mortality? Evidence for EU countries. Appl Econ 36:1717–1722

Flay BR, Petraitis J, Hu FB (1999) Psychosocial risk and protective factors for adolescent tobacco use. Nicotine Tob Res 1:S59–S65

Foster G (2006) It’s not your peers, and it’s not your friends: some progress toward understanding the educational peer effect mechanism. J Public Econ 90:1455–1475

Gaviria A, Raphael S (2001) School-based peer effects and juvenile behaviour. Rev Econ Stat 83:257–268

Gold Dr, Wang X, Speizer FE, Ware JH, Dockery DW (1996) Effects of cigarette smoking on lung function in adolescent boys and girls. N Engl J Med 335:931–937

Harturp WW (1999) Constraints on peer socialization: let me count the ways. Merrill Palmer Q 45:172–183

Keeler T, Hu T, Ong M, Sung H (2004) The US National tobacco settlement: the effects of advertising and price changes on cigarette consumption. Appl Econ 36:1623–1629

Krauth B (2007) Peer and selection effects on youth smoking in California. J Bus Econ Stat 25:288–298

Leatherdale ST, Cameron R, Brown KS, Jolinm MA, Kroeker C (2006) The influence of friends, family and older peers on smoking among elementary students: low-risk students in high-risk schools. Prev Med 42:218–222

Lundborg P (2006) Having the wrong friends? Peer effects in adolescent substance use. J Health Econ 25:214–233

McVicar D (2011) Estimates of peer effects in adolescent smoking across twenty six European countries. Soc Sci Med 73:1186–1193

Manski CF (1993) Identification of endogenous social effects: the refection problem. Rev Econ Stud 60:531–542

Mounts NS, Steimberg L (1995) An ecological analysis of peer influence on adolescent grade point average and drug use. Dev Psychol 31:915–922

Pierani P, Tiezzi S (2009) Addiction and interaction between alcohol and tobacco consumption. Empir Econ 37:1–23

Powell LM, Tauras JA, Ross H (2005) The importance of peer effects, cigarette prices and tobacco control policies for youth smoking behaviour. J Health Econ 24:950–968

Rivers D, Vuong QH (1988) Limited information estimators and exogeneity tests for simultaneous probit models. J Econ 39:347–366

Scal P, Ireland M, Borowsky IW (2003) Smoking among American adolescents: a risk and protective factor analysis. J Commun Health 28:79–97

Smith BJ, Phongsavan P, Bauman AE, Havea D, Chey T (2007) Comparison of tobacco, alcohol and illegal drug usage among school students in three Pacific Island societies. Drug Alcohol Depend 88:9–18

Spanish Government’s Delegation for the National Plan on Drugs (2004) Spanish survey on drug use in the school population

Tauras J, Powell L, Chaloupka F, Ross H (2007) The demand for smokeless tobacco among male high school students in the United States: the impact of taxes, prices and policies. Appl Econ 39:31–41

Taylor R (1993) Risk of premature death from smoking in 15-year-old Australians. Aust J Public Health 17:358–364

Wan J (2006) Cigarette tax revenues and tobacco control in Japan. Appl Econ 38:1663–1675

Wooldridge JM (2002) Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA

Yu J, Williford WR (1992) The age of alcohol onset on alcohol, cigarette, and marijuana use patterns: an analysis of drug use progression of young adults in New York State. Int J Addict 27:1313–1323

Acknowledgments

This work was carried out under project ECO2012-34828 financed by the Spanish Ministry of Economics. The authors thanks the comments received from two anonymous referees. The usual disclaimers apply.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Duarte, R., Escario, J.J. & Molina, J.A. Are estimated peer effects on smoking robust? Evidence from adolescent students in Spain. Empir Econ 46, 1167–1179 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-013-0704-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-013-0704-7