Abstract

The attractiveness of regions and territories for firms, investments, tourists, students, talented people, and other categories is a relevant issue for regional economic development, due to the increasing importance of the relationships and flows on the global scale. The growing concern about this question requires a new comprehensive analytical approach that goes beyond partial approaches. The construction of a synthetic index that measures the territorial attractiveness from a multidimensional perspective is the strategy presented in this work to deal with this issue from a new point of view. We first introduce and present our methodological approach for the construction of the synthetic index, which makes use of both qualitative (budget allocation process) and quantitative (factor analysis) techniques. Our synthetic index is based on the main indicators about incoming flows from abroad (FDIs, workers, tourists, university students). Secondly, we illustrate and discuss the results of its application to the case of the international attractiveness of the Italian regions, based on an 8-year long dataset. The findings reveal that the North–South gap, the well-known Italian spatial pattern, is not fully satisfying to read and interpreter the geographical imbalances in terms of multidimensional territorial attractiveness. Thanks also to the calculation of the Moran’s Index, we show the complexity of the Italian economic geography.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Attractiveness for firms, investments, tourists, talented people, students, and other type of flows, both on the supply and the demand side, is an increasingly important issue for regional economic development. The growing integration of countries and regions due to the globalisation process results in a considerable increase in relationships and flows of, not only goods and services, but also investments and people (Capello et al. 2011; Capello and Dentinho 2012; Fratesi and Senn 2009; Freeman 2006; UNCTAD 2017); thus, creating new models of productive organisation at the international scale known as global value chains (Baldwin 2016; Comotti et al. 2020). The more a region can attract these flows becoming actively part of such, the more it can take benefit from the globalisation process for its economic development.

The importance of the exogenous factors for regional development derives from the awareness that the pure endogenous approach might fail as a development strategy, particularly for lagging areas (Bosworth and Atterton 2012; North and Smallbone 2000; Ward et al. 2005). This is, for example, the case of Southern Italian regions, where about two decades of development policies based on supporting endogenous entrepreneurship were not able to boost significantly economic development (Padovani and Provenzano 2015; Servidio 2015). On the contrary, these regions lost productive factors (human capital, entrepreneurs, etc.), suffering from phenomena such as brain drain (Cersosimo et al. 2015; SVIMEZ 2017; Vecchione 2017) which clearly have damaged their potential of economic development. For these reasons, many scholars realised that Southern Italy need a strategy strongly based also on exogenous development, increasing its ability to retain and attract productive factors, i.e. enhancing its attractiveness.

Clearly, the attraction of flows from outside over a certain limit can even entails not negligible costs for a region. Consider, for example, the consequences of overtourism (Peeters et al. 2018), or the debate on the socio-economic effects of migratory inflows (Edo et al 2018; Mayda et al. 2018). However, first, this is not the case of lagging regions, which evidently, as said above, suffer from a lack of both endogenous and exogenous drivers of development; secondly, the literature on the benefits of attraction of productive factors like investments and human resources is so huge that, in broad terms, the sign and the magnitude of the effects of the attraction of firms and people in a region are out of discussion.

There is a very wide literature on territorial attractiveness, but usually studies on this topic have focused only on one of the types of flows concerned (investments, firms, tourists, creative people, students, etc.). This means that scholars have usually studied and analysed these dimensions of territorial attractiveness separately and partially. For example, many studies have been conducted only on the territorial attractiveness for foreign direct investments (FDIs) (Casi and Resmini 2010; Markusen and Venables 1999; Maza and Villaverde 2015; Phelps and Raines 2003; Villaverde and Maza 2012). Also, there are tens of studies and analyses on the territorial attractiveness for tourists (Butowski 2018; Cracolici and Nijkamp 2008; Crouch and Ritchie 1999; Dann 1996; Enright and Newton 2004; Ruhanen 2007), a topic to which an entire discipline (tourism economics) is devoted. But this topic has very rarely been approached and studied using a comprehensive analytical strategy.

Given the great and growing importance of this topic, it is worthwhile to deal with it following an integrated and multidimensional analytical approach, which means measuring and studying the overall, global attractiveness of regions. This approach, as we will explain, appears innovative in the relevant literature, and according to us can depict a new perspective and provide new stimuli for policy makers.

Ultimately, using this approach means following the same logic applied in the studies concerning territorial competitiveness, a concept which evidently has been investigated and analysed much more than territorial attractiveness. There are several contributions which take a broad and comprehensive approach to the analysis of territorial competitiveness, involving the construction of a synthetic index that encompasses several aspects and components. One of the best-known examples is the Regional Competitiveness Index (RCI) developed by the European Commission (Annoni and Dijkstra 2013). Anyway, as we will see, our synthetic index is something different, as we conceptualise and operationalise attractiveness differently from how the abovementioned scholars did for the RCI, combining a set of indicators never used so far, and using different aggregation technique.

In the following pages, our main objective is first to explain why we need a new perspective to study the complex issue of territorial attractiveness. Secondly, we will present our approach to the multidimensional analysis of territorial attractiveness based on the construction of a synthetic index, focusing on the methodological approach followed and on the quantitative and qualitative techniques used. Thirdly, we will apply this approach to the case of the 20 Italian administrative regions, thus measuring their multidimensional ability to attract different types of flows (investments, tourists, immigrants, students) from other countries (internationally).Footnote 1 The outcome of our analyses are made of rankings of the Italian regions and spatial patterns of Italy. Lastly, we will see and discuss whether these ranking and are coherent with the traditional Italian gap (North–South); thus, whether they can explain the spatial patterns of regional economic development (in terms of GDP per capita) in Italy. For these ultimate objectives, we will use also make use of other “tools”. The Moran’s index and a regression analysis.

We will therefore try to answer the following research questions:

-

Why do we need to define and build a new synthetic measure of territorial attractiveness?

-

How can we build such a synthetic index?

-

What are the outcomes of its application to the case of the 20 Italian regions? What rankings and spatial patterns come out?

-

Does the usual economic geography of Italy (north–South divide) is confirmed? In addition, does this exercise provide new hints on the economic geography of an important country like Italy?

The structure of the paper is as follows. Next, in Sect. 2, we present and discuss the concept of territorial attractiveness, its complexity, and its multidimensional nature. In Sect. 3, we present an overview of the literature on territorial attractiveness, with reference to the latest (few) analyses conducted from a multidimensional perspective (i.e. analyses focused not only on one of the type of flows, like FDI or tourist flows). Then, in Sect. 4, we describe our approach, the spatial units, the geographical scales, and the variables used for the construction of the synthetic index. In Sect. 5, we introduce and explain the methodology used for the construction of the synthetic index, in particular which method of standardisation, weighting, and aggregation we used. In the case of aggregation, we go in-depth in the illustration of the two methods we adopted, the budget allocation process (the participatory approach, which entails going into the field, i.e. we asked a set of experts to assign weights to the different types of attractiveness) and the factor analysis. In Sect. 6, we present and discuss the results concerning the synthetic index with respect to the international attractiveness of the 20 Italian administrative regions, with the help of choropleth maps to enable a direct visual comparison of the findings and the highlighting of the spatial patterns that come out. In Sect. 7, we present the outcome of the application of the Moran’s Index, aimed to analyse to what extent (groups of) Italian regions are similar in terms of international attractiveness, and therefore, they are significantly clustered in one or few values/levels in terms of international attractiveness. Moreover, we present the outcome of the running of the regression model. Finally, in Sect. 8, we draw some conclusions and policy implications.

2 Territorial attractiveness: an anomalous topic with multiple “facets” and interpretations

Territorial attractiveness is a topic of research that intrinsically lends itself to different interpretations, i.e. that has multiple “facets” (Table 1).

For a start, there is the question of conceptualising territorial attractiveness, which can be seen from a number of points of view (Ballotta 2004; Dubini 2004, 2006; Lee 2016; Musolino 2016; Russo et al. 2012; Servillo et al. 2012). First, it can be regarded as ‘revealed attractiveness’, which is associated with the actual incoming flows in a geographical area. When they occur, these incoming flows ‘reveal’ its attractiveness. The size and characteristics of these flows determine the level and peculiarities of its attractiveness. For example, a considerable level of FDIs registered in a certain region "reveals" the attractiveness of that region as a business location. In addition, a large number of non-resident university students "reveal" the attractiveness of that region as an ideal place for higher education.

Secondly, the concept of territorial attractiveness can be seen as ‘perceived attractiveness’, when it refers to how people, or groups, see, perceive, and evaluate a geographical area in which they have a particular interest. For example, this concerns multinational companies interested in investment opportunities, potential migrant workers interested in moving to search for better job opportunities, tourists planning where to go for holidays, etc. According to this second conceptualisation, we do not deal with information about phenomena that have occurred as for the concept of ‘revealed attractiveness’ (actual flows of people, investments, etc.), but instead we deal with the perception, the cognition, and the image of a place.Footnote 2 It is something that can be interpreted and studied by shifting into different scientific disciplines, like behavioural geography, sociology, psychology.

As a third conceptualisation, territorial attractiveness can even be viewed as ‘real attractiveness’. In this respect, we refer to all the factors (infrastructure, services, human capital, innovative capacity, institutions, government, etc.) which enhance the attractiveness of regions, i.e. all factors which are assumed to make an the “host region” attractive. In the case of attractiveness for FDIs, these factors are also called location factors (Dziemianowicz et al 2019; Musolino et al 2022). These factors, intuitively, also serve as explanatory factors of territorial attractiveness as variously defined above (Servillo et al. 2012).

The multiple ‘facets’ of the concept of territorial attractiveness are also determined by its different dimensions: that is to say, the types of flows that a territory can attract. For example, we can have flows of investments (financial resources used to get control of a company, or to settle a new plant, or to invest in real estate), flows of tourists, flows of immigrant workers, or even of other specific categories of people, such as researchers, talented people (called the ‘creative class’), university students.

Finally, we should also not forget that territorial attractiveness can be examined at different spatial scales, from the macro-scale (countries) (Lee 2016) to the micro-geographical scale (municipalities, cities, etc.).

Lastly, we must point out that the concept of territorial attractiveness is different from that of territorial competitiveness (Martin 2003; Martin et al. 2006),Footnote 3 which we have reminded in the introduction. The latter obviously has only one nature: it is just a fact, something concerned with actual economic phenomena. It is not perceived, i.e. it is not concerned at all with aspects such as perception and image. Indeed, differently from territorial attractiveness, there are no studies on the “perception of the competitiveness of a region”.

3 Territorial attractiveness: a topic rarely studied using a comprehensive, all-encompassing approach

As said in the introduction, territorial attractiveness has seldom been studied from a comprehensive, all-encompassing analytical perspective, which aims to include and synthesise all of its different dimensions (types of flows).

As far as revealed territorial attractiveness is concerned, studies generally focused only on one of the many types of flows. For each of them, there is a wide international literature. See, for example, the literature on the territorial attractiveness for foreign direct investments (Casi and Resmini 2010; Markusen and Venables 1999; Phelps and Raines 2003; Villaverde and Maza 2012), which is also rich of contributions on the Italian case (Barba Navaretti et al. 2009; Bentivogli et al. 2015; Comi et al 2021; Daniele and Marani 2011; Resmini 2017; Santangelo 2004; Siemens-Ambrosetti 2007). In addition, there are tens of studies and analyses on the revealed territorial attractiveness for tourists (Butowski 2018; Cracolici and Nijkamp 2008; Crouch and Ritchie 1999; Dann 1996; Enright and Newton 2004; Ruhanen 2007) and for migrant workers, particularly with regard to phenomena such as brain drain and attraction of talented people (Brandi 2014; Beine et al. 2013; Cattaneo et al. 2017; Cersosimo et al. 2015; Ciriaci 2014; De Angelis et al. 2017; Dotti et al. 2013; Halme et al. 2012). Literature on these topics is so huge that these branches of the literature almost represent whole fields of knowledge of the social and economic sciences (think for example of tourism economics), i.e. they are disciplines on their own.

As far as revealed territorial attractiveness is concerned, again scholars generally worked on specific dimensions of attractiveness (for example, perceived attractiveness for foreign direct investments). These studies were generally conducted mostly at the country level or at the macro-regional level. Considering the case of Italy, which is the focus of our analyses, there are several surveys which target the international business community to investigate the relevant location factors that explain, in their opinion, the attractiveness of Italy (see, for example, AmCham 2013; Annushkina and Dubini 2004; IPSOS 2008). There are also some surveys on the Mezzogiorno which aim to analyse its attractiveness either for business or for tourism (Fondazione Nord-Est 2002; GPF&A 2003). Only some specific works have focused on the regional and local scale, particularly the administrative regions and provinces (Musolino 2016, 2018; Musolino et al. 2020).

In the (few) cases, where scholars have adopted a wide and all-encompassing approach,Footnote 4 they accomplished it only partially, or by overlapping and confusing the different conceptualisations of attractiveness.

For example, in the study on Italy undertaken by The European House-Ambrosetti (2016), the authors created an indicator called the GAI (Global Attractiveness Index), with the objective to measure a country's global attractiveness. They took several aspects into account: openness, innovation, endowment, and vulnerability. ‘Openness’ concerns and synthesises different types of flows (FDI, tourists, etc.). The crucial point of such an approach is that first such a synthetic index was constructed only at the country level, but not at the sub-national scale (hence, it is not territorial); secondly, there is an evident ‘confusion’ between different concepts of attractiveness, as they do not distinguish between attraction of flows (revealed attractiveness) and factors of attractiveness (real attractiveness).

Servillo et al. (2012) and or Russo et al. (2012), based on the concept of revealed attractiveness, focused on the attraction of residents and visitors at the NUTS2 EU regions level, with the aim of understanding which are the major determinants of territorial attractiveness. The study identifies some major categories of “real” determinants: environmental capital (protection); human and economic capital (welfare and work); anthropic capital (tourist attraction); socio-cultural capital (welfare and social cohesion); institutional capital (public services).

Also, relevant is the work by Baldazzi et al. (2016), which however focus only on tourist attraction. These authors develop a composite tourist attraction index at the provincial levelFootnote 5 in Italy, combining the perception of the attractiveness of the provinces by tourists with the actual tourist flows, the tourist supply (amount of tourist accommodation), and the environmental and cultural factors. It is an extremely interesting work, but not only it is poorly comprehensive (they focus only on inflows of tourists) but also it combines, without explanation, different concepts of territorial attractiveness 8perceived, revealed and real). In the same way, Garau et al (2020) built a synthetic index of tourist territorial attractiveness, analysing the case of the main Mediterranean islands. However, they also combined different conceptualisation of territorial attractiveness. Another attempt to build a synthetic indicator of territorial attractiveness focused on tourism is the one conducted Casado-Montilla and Pulido-Fernandez (2021) who applied it to the case of six medium-sized inland towns in Andalusia. Here, authors at least did a clear choice as concerns the concept of territorial attractiveness to be adopted.

The contribution by Maza and Villaverde (2015) is extremely interesting as well. It focuses on the construction of a synthetic indicator of territorial attractiveness specific for FDIs. Again, it is a partial synthetic indicator, but it at least is based on a clear conceptualisation of territorial attractiveness, as authors aggregate and merge only variables regarding “real” factors which, according to them, create the potential to attract Foreign Direct Investments in a region (thus, they actually focus on what we have defined above as “real attractiveness”).

Lastly, we can mention some studies that approach the issue of attractiveness using a global analytical perspective, but with an extremely limited geographical scope. For example, we can mention the study by Politecnico di Milano et al. (2010), in which authors analyse the perceived attractiveness of Milan. In addition, a study on Letgallia, a region in Latvia (Ezmale 2012), where the author analysed the perceived attractiveness of this area for residents, tourists, and businesses potentially interested in settling there.Footnote 6 Moreover, there are even some works on islands, such as the Cyclades in Greece (Spilanis et al. 2003), which tried to approach attractiveness in a multidimensional way, but ultimately they paid attention only to the determinants of attractiveness for residents.

To the best of our knowledge, Lee (2016) and Rizzi and Pianta (2012) are the only two studies that tried to encompass all the multiple types of flows in terms of revealed attractiveness (as we will do in our work). Lee (2016) conducted a literature analysis on three disciplines (studies on migration, tourism, and FDIs) at the country scale, conceptualising in a multidimensional framework the country attractiveness. Rizzi and Pianta (2012) conducted an analysis at the regional and local scale, building a synthetic index of the revealed attractiveness of the Italian administrative regions and provinces. Particularly, they were interested in exploring the role of some explanatory variables, such as cultural heritage, environment, and social capital, in the territorial attractiveness. These last two studies are therefore some of the key references for our work.

4 Our multidimensional approach: spatial units, geographical scale and indicators for the analysis of territorial attractiveness

How then is it possible to define and operationalise a global analytical approach to the study of territorial attractiveness, constructing a synthetic index?

First, we considered that we need to keep separate the two main conceptualisations: perceived and revealed territorial attractiveness, as both the nature of these concepts and their theoretical background are so different that this prevented us merging them substantially and meaningfully in one indicator. Here, our approach is based on the concept of revealed attractiveness.

Secondly, having decided to study the case of Italy, we chose as the spatial units of our analysis of territorial attractiveness the 20 Italian administrative regions (i.e. the NUTS2 level, according to the official classification of the EU’s spatial units).Footnote 7 In fact, at this geographical scale, on the one hand, we can have a sufficiently detailed geographical division of Italy, widely used in the territorial analyses of this country; on the other hand, official statistics are available for a sufficiently large number of variables. At a more detailed geographical scale (for example, the Italian provinces, i.e. the EU NUTS3 level), some of these data would be lacking: for example, data about FDIs are not available at this scale in Italy. Instead, at a more aggregated geographical scale (for example, macro-regions: North, Centre, South), the territorial analysis obviously would not make sense.

Thirdly, once we had decided about the spatial units, and given the data availability at that geographical scale, we could identify and select the relevant variables (i.e. the types of flows), which would be the objects of our analysis: direct investments from foreign countries; immigration from abroad; incoming foreign tourist movements; and university students coming from other countries. Direct investments from foreign countries (FDIs) refer to incoming investment flows at the international level: namely, the acquisition of shares in an Italian company (brownfield), or the establishment of a subsidiary in Italy (greenfield), by a foreign investor.Footnote 8 Immigration means the permanent transfer or temporary movement of persons in a country different from their country of origin. Here, due to the lack of adequate data, we could not focus on the skilled part of immigration, which clearly is the type of immigration that matters most in economic terms (e.g. concerning aspects such as human capital and productivity). However, even if rough, we assume that this variable is good enough to measure the ability of a territory to attract human resources from abroad. Finally, as far as the attractiveness for university students is concerned (which can also be seen as embryonic human capital), we refer to foreign students who choose our country for their university education enrolling in one of the Italian universities.

What is necessary to point out is that each of these four types of flows obviously describe extremely relevant phenomena, particularly with respect to Italy. Although Italy is less attractive than some countries in terms of FDIs, in 2018 the incoming FDIs still amounted to about €24 billion (the 15th country in Europe) (ICE 2019). As regards, the attractiveness of tourist flows, according to the World Tourism Organisation (UNWTO, 2020) in 2018 Italy, with 62 million arrivals, was the fifth world tourism country (after France, Spain, US and China). In addition, with reference to immigration from foreign countries, according to Eurostat (2019) in 2019 Italy, with 6.3 million immigrants, was the fifth country in Europe.Footnote 9

As a last step of this stage of our work, we have defined the indicators that compose the international revealed attractiveness of the Italian NUTS 2 regions (Table 2):

-

Attractiveness for foreign direct investments: the ratio of employees working in foreign-owned enterprises in a region to the total resident population of the same region;

-

Attractiveness for foreign tourists: the ratio of foreign overnight stays in a region to the total resident population of the same region;

-

Attractiveness for foreign university students: the ratio of foreign students enrolled in the universities in a region to the total resident population of the same region;

-

Attractiveness for foreign immigrants: the ratio of foreigners settling in a regional territory to the total population of the same region.Footnote 10

From a first glance at the above indicators calculated for the 20 Italian regions (Table 3), we can see that the best performances in terms of attraction are recorded in the North and in the Centre of Italy, whilst most of the South turns out to be scarcely attractive. Apart from the result of Lombardy based on its high attractiveness for FDIs, very positive figures also emerge in other regions like Trentino-Alto Adige, Friuli-Venezia Giulia, Piedmont, Emilia-Romagna, Tuscany and Lazio.

5 The methodology for the construction of a synthetic index

For the construction of the composite index which synthesises the four types of flows that characterise the attractiveness of regions at the international scale, reference is made to the approaches and methodologies defined in the literature.Footnote 11

First of all, our goal was to create a synthetic index that can be compared amongst regions, can be mapped and used by spatial econometrics models. Thereby, considering all advantages of non-aggregative approach (Fattore 2017), the aggregative approach is inevitable in our case. We have objective, quantitative continuous data without polarity issues that helps the aggregation.

As far as the measurement model (the relationship between the phenomenon to be measured—attractiveness—and its measures—the four individual indicators associated with the four types of flows) is concerned, a formative model, as commonly used in social and economic sciences (Mazziotta and Pareto 2017) is applied.

The compensability of the indicators is a key issue to determine the right normalisation and weighting methods. The four fields of attractiveness largely promote compensability. Through the specialisation of regions, some of them will attract direct investments in manufacturing, and others will attract tourists, whilst top universities will attract foreign students. Areas with high touristic flows are not compatible with residential life, or industrial areas are not preferred by tourists. The substitutability is not perfect, but very close to it.

The first step was to define an adequate normalisation method, which would make all ‘sectoral’ indicators comparable. Initially, we thought of using classical standardisation (z-scores), but the point is that this produces some results with a negative sign, which is counter-intuitive for the issue under examination,Footnote 12 and would make necessary an additional step of rescaling (a combination of addition and multiplication). We have therefore opted for normalisation using the Min–Max method,Footnote 13 and a normalisation method that can be derived as follows:

where min (x) and max (x) are, respectively, the minimum and maximum x. Using this method, all data fall within a range from 0 (corresponding to the min (x)) to 1 (corresponding to the max (x)). As a rescaling to another interval is a linear transformation that does not change neither the ranking of the regions nor the correlation between the variables, we kept this data-driven solution. One shortcoming of min–max normalisation is that it can amplify the impact of outliers in the data, and it does not take into account the distribution. So, in presence of outliers and/or very skewed data, the result are also distorted, most values are close to 0 or 1. In our case, the different distributions of the indicators can decrease this distortion effect. The normalisation of the data was executed for each year separately to avoid the distortion effect of structural changes.

Secondly, after the normalisation process, we addressed the question of weighting. We wondered whether all the dimensions of attractiveness (types of flows) have the same weight in the creation of the final synthetic index; that is to say, if they all have the same importance in terms of regional economic development. In order to answer this complex question, which clearly requires extensive expertise and experience on the subject of regional economic development, and as we decided to make of use a transparent and easily understandable weighting method,Footnote 14 we chose the participatory weighting method, known as the BAP (Budget Allocation Process).Footnote 15

This method required us to directly ask a number of experts in regional economic development, by means of a questionnaire, what relative importance they assign to the four dimensions of attractiveness (four types of flows), in terms of their impact on the regional economic development.

The experts were selected amongst academics and representatives of the Italian institutions dealing with research on regional economic development, thus being able to assess the contribution of the various types of flows to regional economic development. They were mainly, but not exclusively, economistsFootnote 16; in any case, they had a broad multidisciplinary background, focused not just on one of the four specific topics associated with the four types of flows taken into consideration (tourism, FDI, immigration, university education). In this respect, our goal was indeed to avoid having a group of experts who were too much biased in favour of one of these topics.

Since a database on such profiles is not available in Italy, experts, according to a non-probabilistic sampling principle, were identified by selecting them amongst the members of some of the major national research institutions working on the matter under consideration. In making this selection and identification of the experts, we also tried to maintain a certain representativeness in terms of geographical origin.Footnote 17

Then, we created an ad hoc electronic questionnaire, in Microsoft Excel format, which we submitted to the selected experts, contacting them by email. Using a total score of 100, the experts could therefore give a weight to the four different types of flows that can be attracted by a region, based on the importance that, broadly speaking, they assigned to each of them for regional economic development. They allocated a budget of 100 points amongst the four different types of flows.

The average weight assigned to each category by the experts was as follows:

-

Attractiveness for direct investments: 38.8%;

-

Attractiveness for tourists: 26.8%;

-

Attractiveness for university students: 19.5%;

-

Attractiveness for immigrants: 14.8%.

It is evident that the weighting given by the experts is far from a mere assignment of equal weights (25% to each category). There are clear differences, and there is therefore a clear hierarchy in terms of relevance for the regional economic development of the four different types of flows. Direct investments are the most important type of flows, according to the experts; this means that they are evaluated as the flows that can have the biggest impact on regional economic development. These are followed in importance by the tourist flows.

Once obtained the weights using the BAP, the final index was created using a linear aggregation method, for which the formula is:

where CIc represents the composite index; n is the number of elementary indicators; and wi is the weight associated with the i-th elementary indicator with \(\sum_{i=1}^{n}{w}_{i}=1\) e 0 ≤ wi ≤ 1.

These weights reflecting the relative importance of the individual variables clearly may change over time, and we recommend repeating the reallocation process (expert survey) after a decade or after an event that significantly redraw investment/tourism/migration/higher education patterns (Booysen 2002). The Covid crisis generated an asymmetric and temporary shock to revealed attractiveness (Uzuner-Ghosh 2021), so whenever data will be available for the post-covid period, a revision will be necessary.

As an alternative aggregation method, as a more complex than weighted average, we also created the composite index using exploratory factor analysis by the method of principal component analysis (PCA). Despite the difficulties of temporal comparability of such an index, it fulfils the necessary conditions of applications (Mazziotta and Pareto 2019) and it is well-adapted to our approach, and it applies a complex aggregation instead of simple one (Mazziotta and Pareto 2017). The four basic indicators are positively correlated, and they can be used without normalisation related to negative polarity. We tested the dataset by the usual precondition methods: Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) and Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity, depending on the period, KMO values were over 0.65 and the p value of the Bartlett’s Test < 0.001. The first principal component extracted containing in a very stable manner 59–61% of the variance of the original indicators served as the indicator of the robustness test. Finally, we recalculated the composite indicator for each year. This alternative indicator allows us to see if a different aggregation method concludes similarly on the regional economics questions. We also run a regression model to find a data-driven weighting of the four variables. The standardised beta values can serve as the relative importance of each variable in the growth of regional GDP.

6 Results: rankings and patterns

The main results coming from our calculation of the synthetic index of the multidimensional attractiveness of the Italian regions show a range from 0 (minimum value) to 1 (maximum value) and are illustrated in the tables below. Table 4 shows the results of the application of the BAP method from 2010 to 2017; Table 5 shows the results based on the application of the factor analysis as aggregating method in the same time interval.

In the highest part of the regional rankings for both methodologies used, evidently far above the other regions along the entire time interval, it is Lombardy. The importance of Lombardy as main gateway for multinational companies in Italy (Mariotti 2017) together with its attractiveness for foreign labour force due to its economic dynamism, and for university students thanks to its numerous and important universities,Footnote 18 can explain the performance of this region.

Lombardy is followed by a group of six regions (scoring on average between 0.4 and 0.6 in the last 3 years in Table 4; and between 0.6 and 0.8 in Table 5): Trentino-Alto Adige, Friuli-Venezia Giulia, Piedmont, Emilia-Romagna, Tuscany and Lazio. The strong and well-known tourist vocation of many of these regions (see for example Trentino-Alto Adige, Piedmont, Tuscany and Lazio for cultural and artistic heritage, food and wine tourism, environmental assets, winter tourism, etc.) and the good level of attractiveness for foreign immigrants are probably the determining factors for the outstanding result of these regions. However, many of them are also rather attractive for FDIs, even though not so much as Lombardy. Interestingly, Lazio can take benefit from the role of the Italian capital city (Rome) as a ‘natural’ investment attractor for multinational companies interested in settling close to the headquarters of the main Italian institutions. Lastly, also, the presence of important universities (see for example important and ancient universities in Bologna, Rome, Pisa) should also not be ignored.

Next, scoring on average between 0.2 and 0.4 in the last 3 years (considering Table 4) and between 0.3 and 0.6 (looking at Table 5), there are seven regions spread throughout North, Centre and South of Italy, but mostly located on the Adriatic side (and almost all them small): Aosta valley, Veneto, Liguria, Marche, Umbria, Abruzzo, Molise. Aosta valley and Veneto have both a good level of incoming foreign tourism (particularly, the former for winter tourism and the latter for summer tourism), and of Foreign Direct Investments, whilst they are less attractive in terms of foreign workers and university students. FDIs flows play an important role also as concerns Liguria. These regions anyway do not show other particularly interesting results.

Lastly, at the bottom of the rankings, there are all the remaining Southern regions. They are neatly divided from the rest of the country, considering the application of both weighting methodologies (in both cases, most of the Southern regions get scores close to 0). Only Calabria obtains a score higher than 0.2, due to good performance in attracting university students and foreign workers from abroad.

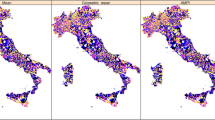

Looking at the cartographic representation of the regional rankings (see Figs. 1 and 2), it emerges that the spatial pattern that traditionally marks the economic geography of the country, the gap between the Central and Northern regions, on the one hand, and the Southern regions, on the other hand (Cannari and Franco 2010; Daniele and Malanima 2007; Musolino 2018; Svimez 2011; Wolleb and Wolleb 1990), neither is rebutted nor is reverted. At a first glance, the two macro-regions differ in terms of multidimensional international attractiveness, but not so neatly: a clear cleavage between two homogenous geographical “blocks” is not visible. Instead, are “nuances”, “new” patterns which make the disparities (and the similarities) in Italy more complex than one could expect, as also recent works on the middle-income trap and development trap of the European regions, including Italian regions, have highlighted (Iammarino et al 2019, 2020; Diemer et al 2022).

Within the central and northern macro-region, the strength in terms of multidimensional international attractiveness of the group of regions extending roughly along the North–South axis, from Milan to Rome, is evident. This area has a specific characteristic, as studied by Beria et al. (2017): it is characterised by a level of transport accessibility considerably higher than other Italian regions, which grew remarkably in the last decades thanks to important investment in rail (high-speed trains) and air transport services and infrastructure. This pattern can be also interpreted in terms of a dichotomic opposition between core (regions along the North–South axis) and periphery (regions out of this axis). The quality of life is also a location factor that might contribute to explain this pattern (Colombo et al 2014). Interestingly, anyway, over the period of time considered the attractiveness of the southern part of this axis (Tuscany, Umbria and Lazio) has weakened.

The spatial pattern which involves the Adriatic axis (Adriatic coastal regions vs not Adriatic coastal regions) appears also interesting, although probably not so “new”. These regions evoke an association with the model of the "Third Italy" and industrial districts (Becattini 1989; Brusco 1982; Garofoli 1991). They are regions with a strong manufacturing specialisation, in sectors of "Made in Italy" such as clothing and footwear, agri-food and furniture, and strongly export-oriented. These regions therefore are characterised more by an endogenous development than by an exogenous development model: this is why probably they are less attractive at the international scale than those located in the core area mentioned above.

Finally, Figs. 1 and 2 show very well that most of the southern regions "languish on their own" in terms of international attractiveness. This spatial pattern emerges visibly from all maps. It is easy to consider that in the international scenario the South is probably strongly disadvantaged by some of its well-known negative contextual factors. First of all, its highly peripheral geographical location in Europe, thus the poor accessibility; but also from other negative location factors, like the presence of the crime organisation and the low level of institutional quality (Daniele and Marani 2011; Musolino 2018; Musolino et al 2018; Nifo and Vecchione 2014).

The only exception in Southern Italy is Abruzzo, Molise and Calabria, which deserve a specific comment. Abruzzo and Molise can be taken as the southernmost part of the Adriatic axis. They have been experiencing since the ‘70 s industrial development based both on industrial districts (Giordano et al 2016), even if not so strong as regions like Tuscany, Marche, and Emilia-Romagna, and on some important exogenous investments, particularly, Abruzzo (Symbola and Hubbruzzo 2019). Not by chance, their level of GDP per capita is closer to that of the central regions.Footnote 19 As far as the result of Calabria is concerned, it looks rather surprising: Calabria indeed is a poor region with the lowest GPD per capita in ItalyFootnote 20 and at a high risk of development trap (Diemer et al 2022). It can be explained, as mentioned above, only with the good level of attractiveness for foreign labour force and university students. The latter is due to the performance of the University of Calabria, located in Cosenza, which grew in the last decades gaining an important role at the regional and national level (Guarascio 2020). The region's ability to attract labour and embryonic human capital from abroad, despite its low level of development, cannot but increase its potential for future economic growth.

7 Spatial patterns at the regional level in terms of international attractiveness. An analysis based on the Moran’s Index

In the analysis that follows, we will present the outcome of the application of the Moran’s Index, with the aim to analyse to what extent Italian regions (or groups of them) are similar in terms of multidimensional international attractiveness. Said differently, we aim to investigate whether Italian regions significantly tend to be clustering, i.e. if they cluster in one or more groups with like value in terms of multidimensional international attractiveness. We will conduct this analysis again for an 8-year long period, from 2010 to 2017. The most widely used indicator of spatial autocorrelation in social-economic studies is Moran’s I (Cliff – Ord 1973, Dusek-Kotosz, 2016). For the spatial weights, we used a relatively simple solution, the rook contiguity: the distance matrix takes.

Based on the scatter plot of the local values and the spatial moving average (here the average of the values in the neighbouring regions), we can find regions with a higher-than-average indicator and surrounded by regions with a higher-than-average indicator and all four combinations of high and low values. These four types of regions can be mapped (Anselin 1995).

As it emerges from Fig. 3, two clusters of regions result to be significantly homogenous and similar: the first includes all northern regions, extended to Tuscany and Umbria, within the high–high category (only Umbria becomes part of the low–high group from 2016 on, whilst Aosta valley “joins” the high–high category after 2015). The second cluster includes most of the Southern regions, excluding Abruzzo and Sardinia, within the low-low category. As far the regions out of these two groups are concerned, there is not statistically significant spatial dependence. We are therefore again in front of spatial patterns which not exactly design the Centre-North vs South divide, as it usually known. Rather, the first cluster might be associated with the “new” core-periphery aforementioned pattern (most of the regions highlighted in red colour overlaps the core regions). Instead, the second cluster clearly identify the marginality of most of the Southern regions in terms of attraction of international flows of investments and people discussed above. Less evident from this analysis is the pattern based on the location along the Adriatic coast.

Interestingly, this clustering pattern changes only slightly along the 8 years period. As mentioned above, only some tiny regions change clusters: from 2016 on Aosta valley becomes part of the first cluster whilst Umbria leaves it and becomes part of the low–high group (in addition, Molise becomes part of the low-low category). Moreover, the Moran’s I does not change along the period: it is true that it declines along the first 5 years (from 0.49 to 0.36), but then, it resurges and roughly reaches the initial level. This means that the level of similarity within these two clusters does not change substantially along the time interval; rather, the internal homogeneity of these two groups consolidates itself along the time. We can point out that the patterns, the shapes of Italy in terms of attractiveness arising from our analyses persistently and structurally mark the economic geography of Italy. As for Southern Italy, paraphrasing Diemer et al (2022) and Iammarino et al (2020), we can say that this part of Italy appears increasingly compactly trapped in its very low level of attractiveness.

The regression model in which the regional GDP (GDP per capita in constant prices) was explained by the four variables of international attractiveness) shows that these four variables can well explain the regional GDP, having an R2 of 0,824. The standardised betas are:

-

0,191 for foreign immigrants.

-

0,469 for foreign tourists.

-

0,164 for foreign university students.

-

0,443 for foreign direct investment.

These coefficients show the relative weight of each element of the attractiveness on regional growth. They are different from the weights estimated by the experts; they more accentuate the role of foreign tourists and foreign investment, the factors that may have positive impact in shorter time than immigrants or students, as they have more direct impact on the economy. A detailed and complex modelling taking into consideration all spatiotemporal aspects of this relationship can better highlight the role of the synthetic indicator, but this modelling is out of the scope of this paper.

8 Concluding remarks

This attempt to construct a synthetic index of territorial attractiveness, based on the key quali–quantitative methods and techniques provided by the relevant literature, has allowed us to analyse how Italian regions perform globally in terms of the attraction of human, financial, entrepreneurial, etc. resources, i.e. in terms of some of key aspects for regional economic development in the age of globalisation. We have been able therefore to cast light comprehensively on the issue of territorial attractiveness, whose importance is evidently on the increase, and on which policymakers should increasingly pay attention in the future to design appropriate regional development strategies. Moreover, we have been able to identify, using also robust econometric tools, the spatial patterns of attractiveness at the international scale. Ultimately, we think that our work has been able to answer our initial research questions.

Clearly, further research is needed in the future in this field to improve many aspects, such as the comprehensiveness of such synthetic index, the methodological robustness and the empirical evidence to be collected. For example, it would be desirable to include possibly a wider range of types of flows in the calculation of the synthetic index. In addition, this index should be possibly applied either to other countries or to other Italian territorial spatial units (for example, provinces). Furthermore, an important next step of this research would be to go further in depth into the explanation of the attractiveness of Italian regions, we mean investigating the determinants of their attractiveness. This can be achieved conducting an econometric analysis which link the synthetic index to its determinants. These may include all tangible and intangible factors which enhance the “real attractiveness” of an area, i.e. supply side characteristics of the location such as entrepreneurship (Fischer and Nijkamp 2009); location on the border (Caragliu 2022); human capital (Faggian et al. 2019); and infrastructure (Del Bo and Florio 2012), amongst many. Nevertheless, this first attempt was quite satisfactory as it suggests a new way of analysing territorial attractiveness and brings out new hints, new lights that can enrich the description and interpretation of the economic geography of a country like Italy.

Interestingly, the results of our analysis based on the construction of the synthetic index were to a certain extent counter-intuitive, showing that the geography of attractiveness in Italy seems less simple than other geographies that typically describe the Italian economy and society. The traditional North–South pattern of regional development does not fully comply with the results of our analysis, as even other scholars recently highlighted. Thus, we bring potentially new elements, new patterns, into the debate concerning regional economic development in Italy. Northern and Central Italy is heterogeneous and apparently more than one spatial pattern overlap, whilst the South lags far behind, being in this respect more homogeneous, with few exceptions (which deserve to be investigated better, see for example the “promising” case of Calabria). The same analysis based on the Moran’s Index tell us that we are in front of patterns which are not exactly the Centre-North vs South divide as we usually know in Italy.

Southern Italy comes out from our analysis as the worst area in Italy in terms of attractiveness of exogenous resources, i.e. the area in Italy which least enjoyed the benefits of the globalisation process. Peripherality, poor accessibility, poor quality of the institutional setting, presence of organised crime, i.e. all locational disadvantages that typically penalise the Mezzogiorno as highlighted by several studies (Barba Navaretti et al. 2009; Bentivogli et al. 2015; Daniele and Marani 2011; Musolino 2018; Musolino et al. 2020; Resmini 2017), are likely to still matter even here. These factors probably affect significantly the spatial behaviour of foreign companies and people when they take decisions about where to locate to Italy.

In this regard, these results have the merit of shedding light on the relevance and priority of specific policies to be adopted for lagging regions. From this point of view, Italy seems to be on the right track. See, for example, policies for attracting investments. Special Economic Zones (PwC 2019), which have recently been established and launched in Southern Italy, are a good strategy to encourage multinationals to settle in the southern regions. But see also policies for reducing the impact of some negative location factors which reasonably affect all dimensions of attractiveness. The National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP) include several promising investment plans in Southern regions, aimed for example at increasing the level of accessibility and connectivity. That means investments in telecommunications and transport infrastructure, i.e. broadband connections, rail infrastructure and services, such as the high-speed railway from Salerno to Reggio Calabria, ports and logistics platforms. Although, this fight yet requires further efforts and perseverance in order to prevent it from discouraging not only exogenous investments but also endogenous entrepreneurship.

Notes

In our analysis, we focused only on the attraction of flows from abroad, due to a limited availability of data about internal flows among regions. Since Italy is a country of a certain demographic and economic size, it may make sense to consider even internal flows (and consequently the attractiveness) of investments, businesses, tourists, workers, university students, etc. flows (and consequently the attractiveness at the national scale). Small countries do not have an internal market (of goods, services, factors, etc.) of a certain size; therefore, they necessarily must open their economy to develop, so flows from foreign countries are fundamental (see for example, Barry 1999; Sluyterman 2005; Sweeney 2008, as concerns the cases of the Netherlands and Ireland). Instead, large countries can primarily count on their internal market for their economic growth (Alesina 2003). As an example, consider that the USA, which has an internal market made up of more than 300 million consumers, is opened to international trade but not so much as other countries: the US degree of commercial openness—exports and imports on GDP—in 2015 was 28%, the 155th position in the world ranking according to the World Bank data (www. theglobaleconomy.com). Italy is not a very small country; therefore, the importance of internal flows cannot be overlooked; however, it is also true that we are not dealing with a large country like the USA. Therefore, we can conclude that excluding internal flows from our analysis are not such a serious matter; in the case of Italy, studying territorial attractiveness on an international scale is much more relevant than studying attractiveness on a national scale.

Perception concerns the way a place is perceived in a psychological sense by each individual. As pointed out by Golledge and Stimson (1987, p. 38), perception is then filtered and stored as knowledge, according to ‘previous cognitive structures in the brain’. In this respect, perception is the subjective part of cognition. As a consequence, according to Meester (2004, p. 29), spatial cognition should be understood as the “objective and subjective knowledge of spatial structures, units and relations”. Place image instead concerns the ‘feelings and impressions about a place’ (Spencer and Dixon 1983), and how it is perceived by individuals or by a group of people. In this second case, the same feelings and impressions about a place are shared by many individuals (Pellenbarg 1985) and become a collective impression of that place. Such impressions can considerably affect and influence the way people behave, as explained by some contributions in the marketing literature (Kotler et al. 1993; Angelis and Dimaki 2011), which distinguish between projected place image (the ideas and impressions of a place available for people’s consideration) and received place image (the result of the interaction between the projected messages and people’s own needs, motivations, preferences, and other personal characteristics).

See also Camagni (2002) for the debate around the conceptualisation and the meaning of territorial competitiveness.

Incidentally, many of these studies focused on Italy.

It is the NUTS3 geographical scale, according to the EU official classification of the spatial units in the European Union made by the European Commission.

In this work, it has been argued that for different subjects priorities are different. For example, for the security of the inhabitants, health, employment and welfare are extremely important; whilst, for entrepreneurs, it is more important that the territory is accessible, has tax incentives, good infrastructure quality, and a good supply of suitable workers.

We had to take into consideration only administrative territorial units, excluding other kinds of spatial division of Italy, although meaningful (for example, functional areas like local labour markets): official statistics about incoming flows are not available for alternative spatial divisions of this country.

According to the IMF (https://www.imf.org/en/About/Glossary), a Foreign Direct Investment is defined as “the acquisition of at least ten percent of the ordinary shares or voting power in a public or private enterprise by non-resident investors. Direct investment involves a lasting interest in the management of an enterprise and includes reinvestment of profits”.

9 There are of course other types of incoming flows absolutely relevant from the economic point of view (for example, investment in real estate, as well as flows related to health services, known as ‘health tourism’), but we did not take them into account in our work because of the lack of data at the regional scale in Italy.

Each of the four indicators is measured on the resident population for two reasons. First, using the resident population as denominator, we can use a common denominator for all of them. Secondly, we assume that using the resident population as denominator is meaningful with respect to the objectives of our research: in fact, we aim to measure the comprehensive ability of an entire region (i.e., of its resident population) to attract different types of flows from abroad (we do not limit ourselves to the measurement of the attractiveness of its productive system or of its universities).

When dealing with the territorial attractiveness for inflows (without considering outflows), it is intuitive that a negative sign does not make sense.

This choice was also dictated by the fact that, for each of the four indicators considered, none of them had values that fall within a very limited range, nor do they have particularly extreme values (outliers) (OECD 2008, ch. 1.5).

OECD 2008, ch. 6.5.

Op. cit.

Although our study concerns economics, we also decided to involve experts specialised in other fields (e.g. geography, spatial planning), since regional economic development is typically assumed to be a multidisciplinary theme.

In total, 18 experts replied and completed the questionnaire: eleven were from Northern Italy, three from the Central Italy, and four from Southern Italy.

In Milan, there are more than 20 Universities: five of them (Università degli Studi di Milano Statale, Politecnico di Milano, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Università Vita-Salute San Raffaele, Università di Milano Bicocca, and Università Luigi Bocconi) are in the QS World University Rankings 2021 (https://www.topuniversities.com/university-rankings).

According to Istat (dati.istat.it), in 2017 GDP per capita at constant prices in Abruzzo was euro 24.389. The Southern Italy average was euro 18.716 (excluding Abruzzo and Molise themselves), whilst the Central Italy average was euro 28.717.

Based on statistics about GDP per capita at constant prices produced by Istat (dati.istat.it).

References

Alesina A (2003) The size of countries: Does it matter? J Eur Econ Assoc 1(2–3):301–316

AmCham (2013) Le imprese americane in Italia. Survey 2013

Angelis V, Dimaki K (2011) A region’s basic image as a measure of its attractiveness. Int J Bus Econ Sci Appl Res 4(2):7–33

Annoni P, Dijkstra L (2013) EU regional competitiveness index. RCI 2013. JRC Scientific and Policy Reports. Publications Office of the European Union. Luxembourg

Annushkina O, Dubini P (2004) Perceived attractiveness of a country system. In: Dubini P (ed) L’attrattività del sistema Paese. Profili territoriali e idealtipi per le imprese. Il Sole 24 Ore, Milano

Anselin L (1995) Local indicators of spatial association—LISA. Geogr Anal 27:94–115

Baldazzi B, Morricone M, Talucci V, Ungaro P (2016) L’impatto turistico nelle regioni italiane: un indicatore composito di attrattività e sostenibilità turistica. In: Mazzola F, Nisticò R (eds) Le regioni europee. Politiche per la coesione e strategie per la competitività. Milano, Franco Angeli

Baldwin R (2016) The great convergence: information technology and the new globalization. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press

Ballotta M (2004) Factors, actions and policies to determine the investment attractiveness of a territorial system. World Bank, WBI/PSD Investment Climate Seminar Series. Washington, January

Barba Navaretti G, Basile R, Benfratello L, Castellani D (2009) Il Mezzogiorno e gli investimenti diretti esteri. Centro Studi Luca D'Agliano

Barry F (1999) Understanding Ireland’s Economic Growth. Palgrave Macmillan UK, London Borough of Camden

Becattini G (1989) From the industrial sector to the industrial district. In: Goodman E, Bamford J (eds) Small firms and industrial districts in Italy. Routledge, London

Beine M, Noël R, Ragot L (2013) The determinants of international mobility of students. CEPII Working Paper, n. 2013–30, September

Bentivogli C, Cherubini L, Iuzzolino G (2015) L'attrattività dei territori: i fattori di contesto. Politica economica, n. 1/2015 Aprile, pp. 3–26. Bologna: Il Mulino

Beria P, Debernardi A, Ferrara E (2017) Measuring the long-distance accessibility of Italian cities. J Transp Geogr 62:66–79

Booysen (2002) An overview and evaluation of composite indices of development. Soc Indic Res 59:115–151

Bosworth G, Atterton J (2012) Entrepreneurial in-migration and neo-endogenous rural development. Rural Sociol 77(2):254–279

Brandi C (2014) L'emigrazione dei ricercatori italiani: cause ed implicazioni. CNR-IRPPS, paper presentato al congresso ISFOL. Roma, Luglio

Brusco S (1982) The Emilian model: productive decentralisation and social integration. Camb J Econ 6(2):167–184

Butowski L (2018) An integrated AHP and PROMETHEE approach to the evaluation of the attractiveness of European maritime areas for sailing tourism. Morav Geogr Rep 26(2):135–148

Camagni R (2002) On the concept of territorial competitiveness: Sound or Misleading? Urban Stud 39(13):2395–2411

Cannari L, Franco D (2010) Il Mezzogiorno e la politica economica dell’Italia. Bank Italy Workshops Conf 4:105–127

Capello R, Dentinho T (2012) Globalization trends and regional development dynamics of FDI and human capital flows. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham

Capello R, Fratesi U, Resmini L (2011) Globalization and regional growth in Europe. Past trends and future scenarios. Springer-Verlag, Berlin

Caragliu A (2022) Better together: untapped potentials in Central Europe. Papers in Regional Science, online first

Casado-Montilla J, Pulido-Fernández JI (2021) How to measure the tourism vocation of a territory? Proposal for a composite index. Int J Tour Res 23(3):253–267

Casi L, Resmini L (2010) Evidence on the determinants of foreign direct investment: the case of EU regions. East J Eur Stud 1(2):93–118

Cattaneo M, Malighetti P, Meoli M, Paleari S (2017) University spatial competition for students: the Italian case. Reg Stud 51(5):750–764

Cersosimo D, Ferrara AR, Nisticò R (2015) La mobilità geografica: da Sud a Nord senza ritorno. In: Viesti G (ed) Nuovi divari. Un’indagine sulle Università del Nord e del Sud. Rapporto RES 2015. Fondazione RES, Roma

Ciriaci D (2014) Does university quality influence the interregional mobility of students and graduates? The Case of Italy. Reg Stud 48(10):1592–1608

Cliff AD, Ord JK (1973) Spatial autocorrelation. Pion, London

Colombo E, Michelangeli A, Stanca L (2014) La Dolce Vita: hedonic estimates of quality of life in Italian cities. Reg Stud 48(8):1404–1418

Comi S, Grasseni M, Resmini L (2021) Can judicial efficiency improve territorial attractiveness to FDI? The Italian experience. Eur J Polit Econ 70:102043

Comotti S, Crescenzi R, Iammarino S (2020) Foreign direct investment, global value chains and regional economic development in Europe. Final Report. European Commission, Directorate-General for Regional and Urban Policy, July. Available at https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/sources/docgener/brochure/foreign_direct_investment_en.pdf (. Accessed 29 Sept 2020

Cracolici MF, Nijkamp P (2008) The attractiveness and competitiveness of tourist destinations: a study of Southern Italian regions. Tour Manage 30(2008):336–344

Crouch GI, Ritchie JRB (1999) Tourism, competitiveness, and societal prosperity. J Bus Res 44(3):137–152

Daniele V, Malanima P (2007) Il prodotto delle regioni e il divario Nord-Sud in Italia (1861–2004). Rivista di Politica Economica 97:267

Daniele V, Marani U (2011) Organized crime, the quality of local institutions and FDI in Italy: a panel data analysis. Eur J Polit Econ 27:132–142

Dann G (1996) Tourists’ image of destination; an alternative analysis. In: FesenmairO’Leary J, Uysal M (eds) Recent advances in tourism marketing research. Haworth Press, New York, pp 41–55

De Angelis I, Mariani V, Torrini R (2017) New evidence on interregional mobility of students in tertiary education: the case of Italy. Politica Economica 1(2017):73–96. https://doi.org/10.1429/86377

Del Bo CF, Florio M (2012) Infrastructure and growth in a spatial framework: evidence from the EU regions. Eur Plan Stud 20(8):1393–1414

Diemer A, Iammarino S, Rodríguez-Pose A, Storper M (2022) The regional development trap in Europe. Econ Geogr 98(5):487–509. https://doi.org/10.1080/00130095.2022.2080655

Dotti N, Fratesi U, Lenzi C, Percoco M (2013) Local labour markets and the interregional mobility of Italian University students. Spat Econ Anal 8(4):443–468

Dubini P (ed) (2004) L’attrattività del sistema Paese. Profili territoriali e idealtipi per le imprese. Il Sole 24 Ore, Milano

Dubini P (ed) (2006) L’attrattività del sistema Paese. Territori, settori, paese. Il Sole 24 Ore, Milano

Dusek T, Kotosz B (2016) Területi statisztika. Akadémiai Kiadó, Budapest?

Dziemianowicz W, Łukomska J, Ambroziak AA (2019) Location factors in foreign direct investment at the local level: the case of Poland. Reg Stud 53(8):1183–1192

Edo A, Ragot L, Rapoport H, Sardoschau S, Steinmayr A (2018) The effects of immigration in developed countries: insights from recent economic research. CEPII Policy Brief No 22

Enright MJ, Newton J (2004) Tourism destination competitiveness: a quantitative approach. Tour Manage 25(6):777–788

Eurostat (2019) Migration and migrant population statistics. Statistics Explained. Available at https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Migration_and_migrant_population_statistics. Accessed from 29 Sept 2020

Ezmale S (2012) Strategies for enhancing attractiveness of the cities in Letgale Region. Eur Integr Stud 6:121–127

Faggian A, Modrego F, McCann P (2019) Human capital and regional development. Handbook of regional growth and development theories

Fattore M (2017) Synthesis of indicators: the non-aggregative approach. In: Maggino F (ed) Complexity in society: from indicators construction to their synthesis. Springer, Cham, pp 193–212

Fischer MM, Nijkamp P (2009) Entrepreneurship and regional development. In Handbook of regional growth and development theories. Edward Elgar Publishing

Fondazione Nord-Est (2002) Nord-Est e Mezzogiorno. Tra nuove relazioni e vecchi stereotipi. FORMEZ, Roma: Donzelli Editore

Fratesi U, Senn L (eds) (2009) Growth and innovation of competitive regions. the role of internal and external connections. Springer-Verlag, Heidelberg

Freeman RB (2006) People flows in globalization. J Econ Perspect 20(2):145–170

Garau C, Desogus G, Stratigea A (2020) Territorial cohesion in insular contexts: Assessing external attractiveness and internal strength of major Mediterranean islands. Eur Plann Stud. pp 1–20

Garofoli G (1991) Modelli locali di sviluppo. Franco Angeli, Milano

Giordano G, Pastore P, Primerano I, Tommaso S (2016) I distretti industriali italiani. Un’analisi comparativa. WP 3.235. DiSES Working Papers, Dipartimento di Scienze Economiche e Statistiche Università degli Studi di Salerno

Golledge RG, Stimson RJ (1987) Analytical behavioural geography. Croom Helm, London

GPF&A (2003) L'immagine del Mezzogiorno d'Italia. Roma: Ministero dell'Economia e delle Finanze-DPS

Guarascio C (2020) Opportunità di sviluppo e periferia. L’esperienza del terziario innovativo in una realtà del Mezzogiorno, la Calabria. Rivista economica del Mezzogiorno. https://doi.org/10.1432/100771

Halme K, Cartalos O, Lähteenmäki-Smith K, Viljamaa K (2012) The attractiveness of the EU for top scientists. Directorate-general for internal policies, Policy Department, Economic and Scientific Policy, European Parliament

Iammarino S, Rodriguez-Pose A, Storper S (2019) Regional inequality in Europe: evidence, theory and policy implications. J Econ Geogr 19(2):273–298

Iammarino S, Rodríguez-Pose A, Storper M, Diemer A (2020) Falling into the middle-income trap? A study on the risks for EU regions to be caught in a middle-income trap, European Commission

ICE (2019) L’Italia nell’economia internazionale. Rapporto ICE 2018–2019. Available at: https://www.ice.it/it/sites/default/files/inline-files/Rapporto%20ICE%202018-2019_completo%20per%20web_1.pdf. Accessed from 29 Sept 2020

IPSOS (2008) Attraction Italy, The opinions of the managers. Milano

Kotler P, Haider DH, Rein I (1993) Marketing places. The Free Press, New York

Lee K (2016) The conceptualization of country attractiveness: a review of research. Int Rev Adm Sci 82(4):807–826

Mariotti I (2017) The attractiveness of Milan and the spatial patterns of international firms. In: Armondi S, Di Vita S (eds) Milan: productions, spatial patterns and urban change. Routledge, London

Markusen JR, Venables AJ (1999) Foreign direct investment as a catalyst for industrial development. Eur Econ Rev 43:335–356

Martin R, Kitson M, Tyler P (eds) (2006) Regional competitiveness. Routledge, London

Martin R (2003) A study on the factors of regional competitiveness. A draft final report for The European Commission Directorate-General Regional Policy

Mayda AM, Peri G, Steingress W (2018) The political impact of immigration: evidence from the United States. Working Paper 24510. NBER Working Paper Series, National Bureau of Economic Research, US: Cambridge, MA. (http://www.nber.org/papers/w24510)

Maza A, Villaverde A (2015) New FDI potential index: design and application to the EU regions. Eur Plan Stud 23(23):2535–2565

Mazziotta M, Pareto A (2017) Synthesis of indicators: the composite indicators approach. In: Maggino F (ed) Complexity in society: from indicators construction to their synthesis. Springer, Berlin

Mazziotta M, Pareto A (2019) Use and misuse of PCA for measuring well-being. Soc Indic Res 142:451–476

Meester WJ (2004) Locational preferences of entrepreneurs: stated preferences in The Netherlands and Germany. Physica-Verlag, Heidelberg

Michela N, Michaela S, Andrea S, Stefano T (2005) Tools for Composite Indicators Building, Joint Research Centre – European Commission. http://farmweb.jrc.cec.eu.int/ci/bibliography.htm

Musolino D (2016) L’attrattività percepita di regioni e province del Mezzogiorno per gli investimenti produttivi. Rivista Economica del Mezzogiorno 30(1):45

Musolino D (2018) The north-south divide in Italy: Reality or perception? Eur Spat Res Policy 25:29–53

Musolino D, Crea V, Marcianò C (2018) Being excellent entrepreneurs in highly marginal areas: the case of the agri-food sector in the province of Reggio Calabria. Eur Countrys 10(1):38–57

Musolino D, Meester WJ, Pellenbarg PH (2020) The mental maps of Italian, German and Dutch entrepreneurs: a comparative perspective. Ann Reg Sci 64:595–613

Musolino D, Meester W, Pellenbarg PH (2022) Stated locational preferences of Italian entrepreneurs: the underlying location factors. Reg Sci Policy Pract 14(4):1005–1021

Nifo A, Vecchione G (2014) Do institutions play a role in skilled migration? The Case of Italy. Reg Stud 48(10):1628–2164

North D, Smallbone D (2000) The Innovativeness and growth of rural SMEs during the 1990s. Reg Stud 34(2):145–157

OECD (2008) Handbook on constructing composite indicators. Methodology and user guide

Padovani R, Provenzano G (2015) La convergenza «interrotta». Il Mezzogiorno del 1951–1992: dinamiche, trasformazioni, politiche, in SVIMEZ (a cura della), La dinamica economica del Mezzogiorno, Bologna, Il Mulino

Peeters P, Gössling S, Klijs J, Milano C, Novelli M, Dijkmans C, Eijgelaar E, Hartman S, Heslinga J, Isaac R, Mitas O, Moretti S, Nawijn J, Papp B, Postma A (2018) Research for TRAN Committee -Overtourism: impact and possible policy responses, European Parliament, Policy Department for Structural and Cohesion Policies, Brussels

Pellenbarg PH (1985) Bedrijfsrelokatie en ruimtelijke kognitie; onderzoekingen naar bedrijfsverplaatsingprocessen en de subjektieve waardering van vestigingsplaatsen door ondernemers in Nederland. Sociaal-geografische Reeks 33. Thesis (PhD). Groningen: Geografisch Instituut Rijksuniversiteit Groningen

Phelps NA, Raines P (2003) the new competition for inward investment: companies, institutions and territorial development. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham

Politecnico di Milano, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Università Commerciale Luigi Bocconi, Università degli studi di Milano, Università degli studi di Milano Bicocca, Università IULM. 2010, Osservatorio marketing territoriale. 1° Rapporto di Competitività ed Attrattività della città di Milano, Milano, Camera di Commercio di Milano e Comune di Milano

PricewaterhouseCoopers (2019) Zone Economiche Speciali. Guida per iniziative di sviluppo nel Mezzogiorno

Resmini L (2017) Patterns of FDI in Southern European Periphery. In: Fonseca M, Fratesi U (eds) Regional Upgrading in Southern Europe: spatial disparities and human capital. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, pp 129–149

Rizzi P, Pianta R (2012) Attrattività, cultura e sviluppo locale. Paper presented at the XXXIII Conference of AISRE (Associazione Italiana di Scienze Regionali), 13–15 September, Rome, Italy

Ruhanen L (2007) Destination competitiveness. In: Matias A, Nijkamp P, Neto P (eds) Advances in modern tourism research. Physica-Verlag, Heidelberg, pp 133–152

Russo A, Smith I, Atkinson R, Servillo L, Madsen B, van der Borg J (2012) ATTREG. The attractiveness of European regions and cities for residents and visitors. Final report. Terragona, ESPON & University Rovira i Virgili

Santangelo GD (2004) FDI and local capabilities in peripheral regions: the Etna valley case. UNCTAD Transnatl Corp 13(1):73–108

Servidio G (2015) Industria meridionale e politiche di incentivazione: storia di un progressivo disimpegno, in SVIMEZ (a cura della), La dinamica economica del Mezzogiorno, Bologna, Il Mulino

Servillo L, Atkinson R, Russo AP (2012) Territorial attractiveness in EU urban and spatial policy: a critical review and future research agenda. Eur Urban Reg Stud 19(4):349–365

Siemens-European House Ambrosetti (2007) Osservatorio Siemens per migliorare l'attrattività positiva del Sistema Italia, Una crescita a piccoli passi. Ricerca, Settembre

Sluytermann KE (2005) Dutch enterprise in the twentieth century. Routledge, London

Spencer CP, Dixon J (1983) Mapping the development of feelings about the city: a longitudinal study of new residents’ affective maps. Trans Inst Br Geogr 8:373–383

Spilanis I, Kondili J, Gryllaki S (2003) Measuring the attractiveness of small islands. A tool for sustainability, http://www.researchgate.net

SVIMEZ (2011) 150 anni di statistiche italiane Nord e Sud 1961–2011. Il Mulino, Bologna

SVIMEZ (2017) Rapporto SVIMEZ 2017 sull’economia del Mezzogiorno. Il Mulino, Bologna

Sweeney P (2008) Ireland’s economic success. Reasons and prospects. Dublin, New Island

Symbola and Hubbruzzo (2019) 100 innovation stories abruzzo. I Quaderni di Symbola, 23 Set 2019

Tarantola (2008) European Innovation Scoreboard: strategies to measure country progress over time. JRC European Communities

The European House-Ambrosetti (2016) Global Attractiveness Index - il vero termometro dell'attrattività di un paese. Presentato al Forum Lo scenario di oggi e di domani per le strategie competitive, Cernobbio, Settembre

UNCTAD (2017) Trade and development report 2017. New York and Geneva: United Nations

UNWTO – World Tourism Organization (2020) World tourism barometer. Volume 18, Issue 1, Jan 2020, pages 1–48

Uzuner G, Ghosh S (2021) Do pandemics have an asymmetric effect on tourism in Italy? Qual Quant 55:1561–1579. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-020-01074-7

Vecchione G (2017) Migrazioni intellettuali ed effetti economici sul Mezzogiorno d’Italia. Rivista economica del Mezzogiorno 3:643–662

Villaverde J, Maza A (2012) Foreign direct investment in Spain: regional distribution and determinants. Int Bus Rev 21:722–733

Ward N, Atterton JH, Kim TY, Lowe PD, Phillipson J, Thompson N (2005) Universities, the knowledge economy and ‘neo-endogenous’ rural development. Working paper, Centre for Rural Economy, Newcastle University, Newcastle, England

Wolleb E, Wolleb G (1990) Divari regionali e dualismo economico. Il Mulino, Bologna

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università Commerciale Luigi Bocconi within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions