Abstract

Dating the regional business cycle phases using a multi-level Markov-switching model revealed that the regional cycle phase transition probability depends on the national cycle phase, although the propagation speed of the national phase into a regional cycle varies across the regions. The estimation of the national factor loadings on regional economies showed that the response of a regional economy to a national impact is mostly greater during a national contraction phase.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

When the national economy is at contraction phase, the time it takes for a regional economy to transit is much shorter. It is well known that agents react faster to bad news in time of recession because late response can greatly hurt the industry.

Burns and Mitchell (1946) defined business cycle as the following: business cycles are a type of fluctuation found in the aggregate economic activity of nations that organize their work mainly in business enterprises: a cycle consists of expansions occurring at about the same time in many economic activities, followed by similarly general recessions, contractions and revivals which merge into the expansion phase of the next cycle. (p. 3)

In NBER Web site of “U.S. Business Cycle Expansions and Contractions” section, it says:

“The NBER does not define a recession in terms of two consecutive quarters of decline in real GDP. Rather, a recession is a significant decline in economic activity spread across the economy, lasting more than a few months, normally visible in real GDP, real income, employment, industrial production, and wholesale-retail sales.”

This paper used a Markov-switching model in identifying the business cycle phases to let the statistical model work as the regional version of the business cycle dating committee.

Thus, a dynamic factor model with a regime switching and an AR(1) structure will require at least four distinct phases defined in order to effectively identify the business cycle phase.

Since many of the national economic indicators that are used in constructing the national business cycle index are aggregated series of regional economic indicators, the assumption that the national business cycle phase transition dynamics are independent from the regional business cycle phases might look unrealistic. However, as noted earlier in the previous section and Fig. 3, the unobserved state of the national economy is assumed to be mostly determined by non-regional factors such as monetary/fiscal policies, international commodity markets and conglomerates business decisions and innovations, national cycle phase works as an exogenous factor in regional cycle phase transition dynamics. Similar structures can be found in international business cycle analysis literature where international (or foreign) variables are exogenous to small open economies. See Buckle et al. (2007), Gjerde and Saettem (1999), Jacobson et al. (2001) and Uribe and Yue (2006) for more details.

By assuming that the national cycle phase is exogenous to the regional cycle phase transition, the national transition dynamics become separated from the regional transition dynamics; thus, we estimate one national-level transition matrix and two regional-level transition matrices for each region. If we do not assume this hierarchical structure between the national and regional cycle phase dynamics, then the national and regional dynamics will become parallel, which is economically implausible. In other words, if regional units also have significant impacts on the national-level cycles, there should be four states (national expansion + regional expansion, national expansion + regional contraction, national contraction + regional expansion, and national contraction + regional contraction) for a region. This implies that if we expand this transition dynamics to 20 MSAs, the number of states will grow to \(2^{21}\), implying more than 4 million entries to estimate, which is practically impossible.

The resulting phase probability, \(S_{rt}\), is not very different even when we use a conventional single-level structure phase transition matrix. The only difference between the multi-level structure Markov-switching model and the single-level structure Markov-switching model is the transition matrix itself.

The list is provided in Appendix 1. All appendices are available at www.real.illinois.edu/d-paper/14/app.pdf.

The list of the deleted observations is provided in Appendix 2.

For the detailed description of IPCA algorithm, see Imtiaz and Shah (2008).

The priors for the parameters are specified as below:

-

\(\mu _{Srt}^r\) and \(\mu _{St}\) are given an uninformative normal prior with mean 0 and precision 0.0001,

-

\(\sigma _{St}\) and \(\sigma _{Srt}^{r}\) are given an uninformative inverse gamma prior with parameter (0.0001, 0.0001), and

-

\(p_{i0} =1-p_{i1}\) and \(p_{r \, i0}^s =1-p_{r \, i1}^s\) are given an uninformative uniform prior Unif(0, 1).

The state parameters, S and Sr are drawn from Bernoulli distribution.

-

Bayesian inference Using Gibbs Sampling for Windows.

The results for other cities are provided in Appendix 3.

The transition matrices of other cities, and the test results whether the transition probability matrices are different during the national expansion phase and the national contraction phase are provided in Appendix 4.

Although the original identification of the business cycle phase has already been incorporated in different variances for each phase, at this stage of analysis, the sources of shock on each regional economy are decomposed into national components, its own regional lag, and idiosyncratic components. Thus, the variance measured in Eq. (7) represents the variance of idiosyncratic part of the regional series, while the variance measured in phase identification stage denotes the total variance of the regional series.

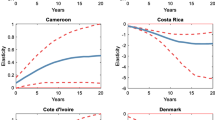

The responses of other cities are presented in Appendix 5.

References

Albert JH, Chib S (1993) Bayes inference via Gibbs sampling of autoregressive time series subject to Markov mean and variance shifts. J Bus Econ Stat 11(1):1–15

Artis M, Krolzig H-M, Toro J (2004) The European business cycle. Oxf Econ Pap 56(1):1–44

Bernanke BS, Boivin J, Eliasz P (2005) Measuring the effects of monetary policy: a factor-augmented vector autoregressive (FAVAR) approach. Q J Econ 120(1):387–422

Buckle RA et al (2007) A structural VAR business cycle model for a volatile small open economy. Econ Model 24(6):990–1017

Burns AF, Mitchell WC (1946) Measuring business cycles. NBER Books, Cambridge

Carlino Gerald A, DeFina Robert H (2004) How strong is co-movement in employment over the business cycle? Evidence from state/sector data. J Urban Econ 55(2):298–315

Carlino G, Sill K (2001) Regional income fluctuations: common trends and common cycles. Rev Econ Stat 83(3):446–456

Carlino Gerald, DeFina Robert (1999) The differential regional effects of monetary policy: evidence from the US states. J Reg Sci 39(2):339–358

Chauvet M (1998) An econometric characterization of business cycle dynamics with factor structure and regime switching. Int Econ Rev 39(4):969–996

Chudik A, Pesaran MH, Tosetti E (2011) Weak and strong cross-section dependence and estimation of large panels. Econom J 14(1):C45–C90

Chung S, Hewings GJD (2015) Competitive and complementary relationship between regional economies: a study of the Great Lake states. Spat Econ Anal. doi:10.1080/17421772.2015.1027252

Crone TM, Clayton-Matthews A (2005) Consistent economic indexes for the 50 states. Rev Econ Stat 87(4):593–603

De Jong P, Shephard N (1995) The simulation smoother for time series models. Biometrika 82(2):339–350

Diebold FX, Rudebusch GD (1994) Measuring business cycles: a modern perspective.” No. w4643. National Bureau of Economic Research

Garcia R, Schaller H (2002) Are the effects of monetary policy asymmetric? Econ Inq 40(1):102–119

Gjerde Øystein, Saettem Frode (1999) Causal relations among stock returns and macroeconomic variables in a small, open economy. J Int Financ Mark Inst Money 9(1):61–74

Hamilton JD (1989) A new approach to the economic analysis of nonstationary time series and the business cycle. Econom J Econom Soc 57(2):357–384

Hamilton JD (2005) What’s real about the business cycle?. No. w11161. National Bureau of Economic Research

Hamilton JD, Owyang MT (2012) The propagation of regional recessions. Rev Econ Stat 94(4):935–947

Harding D, Pagan A (2002) Dissecting the cycle: a methodological investigation. J Monet Econ 49(2):365–381

Hayashida M, Hewings GJD (2009) Regional business cycles in Japan. Int Reg Sci Rev 32(2):119–147

Imtiaz SA, Shah SL (2008) Treatment of missing values in process data analysis. Can J Chem Eng 86(5):838–858

Jacobson T et al (2001) Monetary policy analysis and inflation targeting in a small open economy: a VAR approach. J Appl Econom 16(4):487–520

Karras G (1996) Are the output effects of monetary policy asymmetric? Evidence from a sample of European countries. Oxf Bull Econ Stat 58(2):267–278

Kaufmann S (2000) Measuring business cycles with a dynamic Markov switching factor model: an assessment using Bayesian simulation methods. Econom J 3(1):39–65

Kim C-J, Nelson CR (1998) Business cycle turning points, a new coincident index, and tests of duration dependence based on a dynamic factor model with regime switching. Rev Econ Stat 80(2):188–201

Kouparitsas M (2001) Is there a world business cycle? Fed Reserve Bank Chicago Working Pap 172:12

Leiva’Leon D (2012) Monitoring synchronization of regional recessions: a Markov switching network approach. In: The twelfth annual Missouri economics conference, St Louis Federal Reserve website

Lucas Jr RE (1977) Understanding business cycles. In: Carnegie-Rochester conference series on public policy, vol 5. North-Holland

Nelson PRC, Taylor PA, MacGregor JF (1996) Missing data methods in PCA and PLS: score calculations with incomplete observations. Chemometr Intell Lab Syst 35(1):45–65

Owyang Michael T et al (2008) The economic performance of cities: a Markov-switching approach. J Urban Econ 64(3):538–550

Owyang MT, Piger J, Wall HJ (2005) Business cycle phases in US states. Rev Econ Stat 87(4):604–616

Park Y, Hewings GJD (2012) Does industry mix matter in regional business cycles? Stud Reg Sci 42:39–60

Partridge MD, Rickman DS (2005) High-poverty nonmetropolitan counties in America: Can economic development help? Int Reg Sci Rev 28(4):415–440

Potter SM (1995) A nonlinear approach to US GNP. J Appl Econom 10(2):109–125

Ravn MO, Sola M (2004) Asymmetric effects of monetary policy in the United States. Rev Fed Res Bank Saint Louis 86:41–58

Rissman ER (1999) Regional employment growth and the business cycle. Econ Perspect Fed Res Bank Chicago 23(4):21–41

Scott IO Jr (1955) The regional impact of monetary policy. Q J Econ 69(2):269–284

Sichel DE (1994) Inventories and the three phases of the business cycle. J Bus Econ Stat 12(3):269–277

Stock JH, Watson MW (1989) New indexes of coincident and leading economic indicators. NBER Macroecon Annu 4:351–409

Toshiaki W (2003) Measuring business cycle turning points in Japan with a dynamic Markov switching factor model. Monet Econ Stud 21(1):35–68

Uribe M, Yue VZ (2006) Country spreads and emerging countries: Who drives whom? J Int Econ 69(1):6–36

Wall HJ (2006) Regional business cycle phases in Japan. Working Paper 2006–053A, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, St. Louis

Acknowledgments

I would like to express my gratitude to Anil K. Bera, Bernard Fingleton, Michael T. Owyang, Jason Bram and other anonymous referees for their valuable comments on this paper. With their comments and the support from my greatest academic advisor, Geoffrey J.D. Hewings, this paper could win 2015 Tiebout Prize.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chung, S. Assessing the regional business cycle asymmetry in a multi-level structure framework: a study of the top 20 US MSAs. Ann Reg Sci 56, 229–252 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00168-015-0732-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00168-015-0732-7