Abstract

Purpose

Customised individually made (CIM) total knee arthroplasty (TKA) was introduced to potentially improve patient satisfaction and other patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs). The purpose of this study was to compare PROMs, especially patient satisfaction, of patients with CIM and OTS TKA in a matched-pair analysis with a 2-year follow-up.

Methods

This is a prospective cohort study with a propensity score matching of 85 CIM and 85 off-the-shelf (OTS) TKA. Follow-up was at 4 months, 1 year and 2 years. The primary outcome was patient satisfaction. Secondary outcomes were as follows: overall improvement, willingness to undergo the surgery again, Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS), Forgotten Joint Score (FJS-12), High-Activity Arthroplasty Score (HAAS), EQ-5D-3L, EQ-VAS, Knee Society Score (KSS) and surgeon satisfaction.

Results

Patient satisfaction ranged from 86 to 90% and did not differ between CIM and OTS TKA. The EQ-VAS after 4 months and the HAAS after 1 year and 2 years were higher for CIM TKA. KOOS, FJS-12 and EQ-5D-3L were not different at follow-up. The changes in KOOS symptoms, pain and daily living were higher for OTS TKA. The KSS was higher for patients with CIM TKA. Surgeon satisfaction was high throughout both groups. Patients who were satisfied after 2 years did not differ preoperatively from those who were not satisfied. Postoperatively, all PROMs were better for satisfied patients. Patient satisfaction was not correlated with patient characteristics, implant or preoperative PROMs, and medium to strongly correlated with postoperative PROMs.

Conclusion

Patient satisfaction was high with no differences between patients with CIM and OTS TKA. Both implant systems improved function, pain and health-related quality of life. Patients with CIM TKA showed superior results in demanding activities as measured by the HAAS.

Level of evidence

II, prospective cohort study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Achieving a high percentage of satisfied patients after a total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is still challenging. Despite the success of TKA, about 20% of patients remain dissatisfied [1,2,3]. Several factors and predictors have been identified [2, 4,5,6,7,8,9], with persistent pain and limited function being the main reasons for patient dissatisfaction [10]. To better understand the patients’ perspective, the analysis of patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs), and patient satisfaction in particular, is inevitable. From a patient-centred perspective, a TKA is only successful if the patient is satisfied with the outcome.

Customised individually made (CIM) TKAs were introduced in 2011 [11]. CIM implants are manufactured based on a computed tomography scan of the affected leg. The underlying concept is to respect the anatomical variability and to restore the individual anatomy, thereby improving knee kinematics. Off-the-shelf (OTS) TKAs can cause implant overhang, malalignment and abnormal kinematics [12,13,14,15]. CIM TKAs were designed to overcome these limitations and to improve clinical outcome and patient satisfaction. The high variability in morphology supports the evolution towards CIM TKA to potentially achieve better bone–implant fit [16, 17].

Studies have shown encouraging results with CIM TKA regarding knee alignment [18, 19], improved function [20] and patient satisfaction [21, 22]. Recent systematic reviews found conflicting evidence with superior and inferior results for clinical and patient-reported outcomes with CIM TKA [23,24,25]. However, they highlighted the need for better methodological studies.

A prospective study of CIM TKA with a matched-pair control group focussing on PROMs is currently not published. The purpose of this study was to compare PROMs, especially patient satisfaction, of patients with CIM and OTS TKA in a matched-pair analysis with a 2-year follow-up. Our hypothesis was that patients with CIM TKA would have a higher rate of patient satisfaction than patients with OTS TKA.

Materials and methods

Study design, setting and recruitment

This is a single-side, observational, prospective cohort study with matched-pair analyses comparing patients with CIM and OTS TKA. The study was conducted in accordance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki [26] and approved by the local ethics committee (reference: 2016-01777).

Patients were recruited in our medical practise. Routinely, all of our TKA patients were asked to complete a set of PROMs. Details regarding recruitment and procedures are published elsewhere [27]. In brief, after signed consent, patients completed PROMs before the surgery, at 4 months, 1 year and 2 years. In the current study, we included consecutive patients with a primary cruciate-retaining CIM TKA (iTotal® CR G2, Conformis Inc., Billerica, MA, US) or primary cruciate-retaining OTS TKA (Attune® CR mobile-bearing, DePuy Synthes, Raynham, MA, US) who completed PROMs before the surgery and after 2 years. Patients were excluded if they had a major re-operation with potential impact on the TKA or revision.

Implants and surgery technique

The CIM TKA implant is based on a preoperative computed tomography. The surgeon is provided with a customised implant and customised instruments. The concept and surgical technique are described elsewhere [28]. In brief, the distal femoral resection is performed using a patient-specific cutting block and the tibial resection is performed using a cutting jig for the patient-specific anatomical slope. Patient-specific spacers are used to balance the knee in extension and flexion. The planning algorithm aims for a hip–knee–ankle angle of 180° and a limited joint line obliquity due to uneven medial and lateral inlay heights.

The Attune implant used in the control group is the most commonly used OTS implant in Switzerland [29]. OTS TKA was performed with conventional instrumentation and mechanical alignment. A natural slope and rotation along the grinding marks on the arthritic tibial plateau is aimed for, followed by resection of the tibial plateau. After determining the femoral rotation with the intramedullary balancer, the distal femur is resected first (extension gap). This is followed by a posterior (flexion gap) and anterior femoral condylar resection.

All TKAs were performed between January 2017 and December 2020 by MPA (CIM and OTS) and by TR and RK (OTS). All surgeons had many years of experience in TKA and a high volume of operations. The same perioperative and postoperative anaesthesia and pain management protocol were used for all patients as well as a medial parapatellar approach without tourniquet. The postoperative rehabilitation protocol was the same for all patients and included immediate full weight-bearing on crutches until sufficient muscular stabilisation was achieved.

Data collection

Data were collected during routine visits before the surgery, after 4 months, 1 year and 2 years using Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap®). Table 1 provides a detailed overview of the measures and data collection. Patients’ characteristics were extracted from the medical records. Osteoarthritis was classified according to Kellgren and Lawrence (KL) grade from 0 (no osteoarthritis) to 4 (severe osteoarthritis) [30] and comorbidities according to the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) from ASA I (normal healthy) to ASA V (moribund) [31].

The primary outcome was patient satisfaction on a five-point Likert scale. Patients were summarised as satisfied (‘very satisfied’ or ‘satisfied’) and not satisfied (‘neutral’, ‘unsatisfied’ or ‘very unsatisfied’). Secondary outcomes were all other PROMs: overall improvement (‘very much better’ or ‘substantially better’ were summarised as improved, the rest as not improved), the willingness to undergo the surgery again, the Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS), the Forgotten Joint Score (FJS-12), the High-Activity Arthroplasty Score (HAAS) and the EQ-5D-3L for health-related quality of life including a visual analogue scale (VAS).

In addition, surgeons completed the objective part of the Knee Society Score (KSS), also known as KSS-Knee, and rated their satisfaction with the surgery. Similar to patient satisfaction, ‘very satisfied’ and ‘satisfied’ were combined as satisfied. The KSS was not available after 2 years, because it required a follow-up visit, which was not routine for all patients.

Postoperative complications such as thromboembolic event, infection, re-operation, revision or decease were recorded as adverse events. Revision was defined as a re-operation to replace some or all parts of the original TKA.

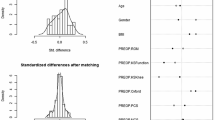

Sample size and matching

The a priori power calculation was based on a calculated mean effect size of 0.5 across all measures. This resulted in a sample size of 85 TKAs per group to assure a power of 0.9 with a two-sided alpha of 0.05. To reduce the bias introduced by the non-randomised study design and to adjust for differences in patients’ characteristics, we performed a propensity score matching based on the variables age, body mass index (BMI), sex, KL grade and ASA score. Of 85 CIM and 202 OTS TKA with available 2-year PROMs, 85 CIM were matched to 85 OTS TKA (Fig. 1).

Statistics

Descriptive statistics comprise mean and standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables, frequency count and percentage for categorical variables. Differences between preoperative and postoperative data were measured with paired t test. Differences between groups were measured with unpaired t test for continuous variables and with Mann–Whitney U test or Chi-square test for categorical variables. Bivariate linear correlations were analysed using the Spearman test, with effect sizes interpreted as low (r ≈ 0.1), medium (r ≈ 0.3) or strong (r ≈ 0.5) [32]. Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS statistics for Windows, version 29, Armonk, NY: IBM Corp and R, version 4.1.3 [33]. Matching was performed using the MatchIt package in R, version 4.5.3.

Results

Recruitment and baseline measures

The matched-pair data of 85 CIM TKA (70 patients, 34 women) and 85 OTS TKA (78 patients, 33 women) was analysed. Details to recruitment are described in Fig. 1 and patients’ characteristics in Table 2. Patients with CIM TKA had more often a supplementary insurance which is required in Switzerland to cover costs for a CIM TKA. Patients with CIM TKA had more often a staged bilateral surgery and at baseline higher PROMs and a lower KSS (Table 2).

Postoperative measures

PROMs

Patient satisfaction after 2 years was 88% for CIM and OTS TKA (Table 3 and Fig. 2). Overall, eight patients (5%) were not satisfied after 1 year but were satisfied after 2 years and seven patients (4%) were satisfied after 1 year but not satisfied after 2 years. All other patients (91%) had no change in patient satisfaction. Almost all patients reported an overall improvement and would undergo the surgery again (Table 3). All other PROMs improved for all patients from baseline to each follow-up (4 months, 1 year and 2 years), as well as from 4 months to 1 year and from 1 to 2 years (p < 0.001 each). Sole exception was the EQ-VAS with a mean change of − 0.7 from 1 to 2 years (p = 0.218).

When comparing patients with CIM and OTS TKA, the EQ-VAS after 4 months and the HAAS after 1 year and 2 years were clearly higher for patients with CIM TKA (Table 3, Fig. 3). All other PROMs were not different in their end scores. Change scores of PROMs were higher for patients with OTS TKA from baseline to each follow-up with clearly higher values for KOOS symptoms, pain and daily living (Table 5, additional material).

KSS and surgeon satisfaction

The KSS improved for all patients from baseline to 4 months and from baseline to 1 year (p < 0.001). KSS end and change scores were higher for patients with CIM TKA (p < 0.001, Table 3 and additional material: Table 5). Surgeon satisfaction after 1 year was 96% for CIM and 92% for OTS TKA (p = 0.382, Table 3). The correlation between patient and surgeon satisfaction was strong (4 months: r = 0.418, p < 0.001; 1 year: r = 0.483, p < 0.001).

Satisfied compared to not satisfied patients

Patients who were satisfied after 2 years did not differ at baseline from patients who were not satisfied (Table 4). At each follow-up, all PROMs and the KSS were higher for patients who were satisfied after 2 years (Table 4; Fig. 4). Likewise, the change scores for all PROMs and the KSS were higher for satisfied patients (additional material: Table 6).

Patient satisfaction was not correlated with patients’ characteristics (age, BMI, sex, insurance, side, bilateral surgery, KL grade, ASA), implant or baseline measures. The correlation between patient satisfaction and measures after 1 year was medium for HAAS (r = 0.365, p < 0.001) and strong for KOOS, FJS-12, EQ-5D-3L, EQ-VAS and KSS (r > 0.411, p < 0.001). The correlation between patient satisfaction and measures after 2 years was medium for HAAS (r = 0.356, p < 0.001) and EQ-VAS (r = 0.333, p < 0.001) and strong for KOOS, FJS-12, EQ-5D-3L (r > 0.432, p < 0.001).

Adverse events

At the last follow-up, 1 patient with CIM TKA and 3 patients with OTS TKA had died. Four revisions occurred: 2 CIM TKA after 17 and 26 months and 2 OTS TKS after 8 and 9 months, respectively. The revision rate was 2.4% in both groups. One patient with CIM TKA needed a major re-operation due to a quadriceps rupture after 19 months. These patients were excluded from the analysis (Fig. 1).

Of the patients included in the matched-pair analysis, 3 patients with CIM TKA and 1 patient with OTS TKA had an adverse event. Two patients, 1 with CIM and 1 with OTS TKA, required diagnostic arthroscopy to exclude an infection (both negative) and 2 patients with CIM TKA required arthrolysis.

Discussion

The most important finding was that patient satisfaction after 2 years was high and not different between patients with CIM and OTS TKA. Thus, our hypothesis was not confirmed. Preoperatively, patients with a CIM TKA tended to have less subjective impairment and presented with higher PROMs. Postoperatively, patients with CIM TKA had a higher EQ-VAS after 4 months and a higher HAAS after 1 year and 2 years. All other PROMs were not different regarding the end scores between CIM and OTS TKA. The change scores of PROMs were higher for OTS TKA, especially for KOOS symptoms, pain and daily living.

The objective KSS was higher postoperatively for CIM TKA. Surgeon satisfaction was not different between CIM and OTS TKA and was strongly correlated with patient satisfaction. Patients who were satisfied after 2 years were clearly better on all PROMs and the KSS compared to patients who were not satisfied after 2 years.

Our results regarding patient satisfaction are within the spectrum of current TKA studies or registry reports [4, 10, 34, 35]. The results are also consistent with other CIM TKA studies. The largest retrospective study to date included 540 CIM TKA and found a satisfaction rate of 89% after a mean follow-up of 2.8 years (range 0.1–7.0) [22]. The authors reported a KOOS for Joint Replacement (KOOS-JR) of 82 points and a revision rate of 1.5%. The only study to date with a long-term follow-up found very good and stable results over 5 years [20]. Patient satisfaction was not analysed, but they found a mean KSS of 92 points, a mean WOMAC of 11 points and a revision rate 1.4% after 5 years. A study with posterior-stabilised CIM TKA (iTotal® PS, Conformis Inc., Billerica, MA, US) reported a high satisfaction rate of 90% for 100 CIM TKA after a mean follow-up of 1.9 years (range 1.5–2.4) [36].

Comparative CIM TKA studies are still sparse. Our own group found no differences in patient satisfaction and other PROMs after 1 year in an unmatched comparison of 74 CIM and 169 OTS TKA [37]. Satisfaction rates were similar to the present study (CIM 87%, OTS 89%). Others found better clinical outcome and higher fulfilment of expectations for patients with CIM TKA after 1 year, although in a small sample of 33 CIM and 31 OTS TKA [38]. Another study examined PROMs of 47 CIM and 47 OTS TKA in the same patients with staged bilateral surgery. After a mean follow-up of 2.3 years (range 0.7–3.8), they found better results for CIM TKA regarding KOOS-JR, FJS-12, pain, mobility, stability and normal feeling of the knee. In summary, 72% of the patients preferred the CIM TKA, 21% saw no difference and 6% preferred the OTS TKA [39].

The strong correlation between patient satisfaction and PROMs at follow-up is consistent with other studies [4, 40]. In contrast to others, there was no correlation between dissatisfaction and younger age [4, 5, 9], higher BMI [4, 8], female sex [8] or low preoperative PROMs [4].

Most of the improvement in all PROMs and the KSS occurred quite early, within the first 4 months. By the 4-month follow-up, we found a clear difference in all measures for patients who were later satisfied and those who were not. Others also reported early different satisfaction profiles as early as 6 weeks [40] or after 3 months [41]. PROMs could support the early identification of dissatisfied patients and enable clinicians to intervene in a timely and targeted way to improve patient outcomes [40]. Nevertheless, all measures in our study improved considerably by the 2-year follow-up. However, the proportion of patients who went from being satisfied after 1 year to being not satisfied after 2 years, and vice versa, was rather small (9%). Others have also found no change in patient satisfaction from 6 months to 2 years [40] or only rare changes from 1 to 3 years [42].

As of 2018, another CIM TKA system is available, the Symbios Origin® implant (Symbios, Yverdon-les-Bains, Switzerland) [43]. After promising first results [44], a large improvement in the KSS was recently shown, with a mean KSS of 94 points after 1 year [45]. Another study reported a high satisfaction rate of 94% after a mean follow-up of 2.8 years [46]. KOOS and FJS-12 results in this study were similar or slightly lower than our results after 2 years. Others found satisfactory early clinical and radiographic outcomes for this CIM TKA in patients with prior osteotomies or extra-articular fracture sequelae [47].

The strength of our study is the prospective matched-pair design which has not been previously published for CIM TKA. We applied a profound set of PROMs and analysed the data at multiple follow-ups, whilst having a reasonable number of drop-outs. Nevertheless, our study has some limitations. First, although the data were collected prospectively, a selection bias is possible due to the lack of randomisation. On the other hand, it must be recognised that patients in a private clinic setting would not accept this scientifically interesting randomisation. For practical reasons, this bias is, therefore, unavoidable. Selection bias also occurred because supplementary insurance is required to be eligible for CIM TKA.

Propensity score matching was used to limit bias and ensure a degree of homogeneity. The 2-year follow-up is only mid-term, but CIM TKAs are still relatively new and not widely used. However, for studies with PROMs as primary outcome, it was shown that a 1-year follow-up is sufficient, as results remain consistent with longer follow-up [48, 49]. Longer follow-up is preferable for implant survival. Our 2-year revision rate was 2.4% in both groups, which is lower than the reported overall 2-year revision rate of 3.5% reported in the Swiss Implant Registry (iTotal: 2.3%, Attune: 4.2%) [29]. The loss to follow-up of patients who did not return their PROMs questionnaire was 9% after 2 years. Despite constant efforts, including postal or e-mail reminders and telephone calls, achieving a high PROMs response rate at multiple time points has proven to be challenging [50].

Conclusion

We found a high patient satisfaction after 1 year and after 2 years, which did not differ between patients with CIM and OTS TKA. The HAAS, which is designed to capture improvements in activities to recreational sports level, was superior for patients with CIM TKA. All other PROMs did not differ in terms of end scores. Change scores were higher for OTS TKA, especially for KOOS symptoms, pain and daily living. Both implant systems apparently improved function, pain and health-related quality of life.

References

Bourne RB, Chesworth BM, Davis AM, Mahomed NN, Charron KDJ (2010) Patient satisfaction after total knee arthroplasty: who is satisfied and who is not? Clin Orthop 468(1):57–63

Kahlenberg CA, Nwachukwu BU, McLawhorn AS, Cross MB, Cornell CN, Padgett DE (2018) Patient satisfaction after total knee replacement: a systematic review. HSS J 14(2):192–201

Verhaar J (2020) Patient satisfaction after total knee replacement-still a challenge. Acta Orthop 91(3):241–242

Ayers DC, Yousef M, Zheng H, Yang W, Franklin PD (2022) The prevalence and predictors of patient dissatisfaction 5-years following primary total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 37(6S):S121–S128

Farooq H, Deckard ER, Ziemba-Davis M, Madsen A, Meneghini RM (2020) Predictors of patient satisfaction following primary total knee arthroplasty: results from a traditional statistical model and a machine learning algorithm. J Arthroplasty 35(11):3123–3130

Gunaratne R, Pratt DN, Banda J, Fick DP, Khan RJK, Robertson BW (2017) Patient dissatisfaction following total knee arthroplasty: a systematic review of the literature. J Arthroplasty 32(12):3854–3860

Maratt JD, Lee Y, Lyman S, Westrich GH (2015) Predictors of satisfaction following total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 30(7):1142–1145

Pronk Y, Peters MCWM, Brinkman J-M (2021) Is patient satisfaction after total knee arthroplasty predictable using patient characteristics and preoperative patient-reported outcomes? J Arthroplasty 36(7):2458–2465

Scott CEH, Oliver WM, MacDonald D, Wade FA, Moran M, Breusch SJ (2016) Predicting dissatisfaction following total knee arthroplasty in patients under 55 years of age. Bone Jt J 98-B(12):1625–1634

Halawi MJ, Jongbloed W, Baron S, Savoy L, Williams VJ, Cote MP (2019) Patient dissatisfaction after primary total joint arthroplasty: the patient perspective. J Arthroplasty 34(6):1093–1096

Conformis (2011) https://www.conformis.com/about-conformis/news/conformis-receives-ce-mark-certification-for-itotal-cr-patient-specific-total-knee-resurfacing-system/. Accessed 10 Sept 2022

Bonnin MP, Schmidt A, Basiglini L, Bossard N, Dantony E (2013) Mediolateral oversizing influences pain, function, and flexion after TKA. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 21(10):2314–2324

Li K, Saffarini M, Valluy J, Desseroit M-C, Morvan Y, Telmon N, Cavaignac E (2019) Sexual and ethnic polymorphism render prosthetic overhang and under-coverage inevitable using off-the shelf TKA implants. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 27(7):2130–2139

Mahoney OM, Kinsey T (2010) Overhang of the femoral component in total knee arthroplasty: risk factors and clinical consequences. J Bone Jt Surg Am 92(5):1115–1121

Simsek ME, Akkaya M, Gursoy S, Isik C, Zahar A, Tarabichi S, Bozkurt M (2018) Posterolateral overhang affects patient quality of life after total knee arthroplasty. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 138(3):409–418

Beckers L, Müller JH, Daxhelet J, Ratano S, Saffarini M, Aït-Si-Selmi T, Bonnin MP (2023) Considerable inter-individual variability of tibial geometric ratios renders bone-implant mismatch unavoidable using off-the-shelf total knee arthroplasty: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 31(4):1284–1298

Beckers L, Müller JH, Daxhelet J, Saffarini M, Aït-Si-Selmi T, Bonnin MP (2022) Sexual dimorphism and racial diversity render bone-implant mismatch inevitable after off-the-shelf total knee arthroplasty: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 30(3):809–821

Arbab D, Reimann P, Brucker M, Bouillon B, Lüring C (2018) Alignment in total knee arthroplasty—a comparison of patient-specific implants with the conventional technique. Knee 25(5):882–887

Wunderlich F, Azad M, Westphal R, Klonschinski T, Belikan P, Drees P, Eckhard L (2021) Comparison of postoperative coronal leg alignment in customized individually made and conventional total knee arthroplasty. J Pers Med 11(6):549

Steinert AF, Schröder L, Sefrin L, Janßen B, Arnholdt J, Rudert M (2022) The impact of total knee replacement with a customized cruciate-retaining implant design on patient-reported and functional outcomes. J Pers Med 12(2):194

Reimann P, Brucker M, Arbab D, Lüring C (2019) Patient satisfaction—a comparison between patient-specific implants and conventional total knee arthroplasty. J Orthop 16(3):273–277

Schroeder L, Pumilia CA, Sarpong NO, Martin G (2021) Patient satisfaction, functional outcomes, and implant survivorship in patients undergoing customized cruciate-retaining TKA. JBJS Rev 9(9):e20.00074

Moret CS, Schelker BL, Hirschmann MT (2021) Clinical and radiological outcomes after knee arthroplasty with patient-specific versus off-the-shelf knee implants: a systematic review. J Pers Med 11(7):590

Müller JH, Liebensteiner M, Kort N, Stirling P, Pilot P, European Knee Associates (EKA), Demey G (2023) No significant difference in early clinical outcomes of custom versus off-the-shelf total knee arthroplasty: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 31(4):1230–1246

Victor J, Vermue H (2021) Custom TKA: what to expect and where do we stand today? Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 141(12):2195–2203

WMA Declaration of Helsinki—Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects (2023). https://www.wma.net/publications/wma-doh-1964-2014/. Accessed 15 May 2023.

Vogel N, Rychen T, Kaelin R, Arnold MP (2020) Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) following knee arthroplasty: a prospective cohort study protocol. BMJ Open 10(12):e040811

Steinert AF, Sefrin L, Jansen B, Schröder L, Holzapfel BM, Arnholdt J, Rudert M (2021) Patient-specific cruciate-retaining total knee replacement with individualized implants and instruments (iTotal™ CR G2). Oper Orthop Traumatol 33(2):170–180

SIRIS Report Hip & Knee (2023) http://www.siris-implant.ch/de/Downloads&category=16. Accessed 10 Jun 2023.

Kohn MD, Sassoon AA, Fernando ND (2016) Classifications in brief: Kellgren–Lawrence classification of osteoarthritis. Clin Orthop Relat Res 474(8):1886–1893

ASA Physical Status Classification System (2023) https://www.asahq.org/standards-and-guidelines/statement-on-asa-physical-status-classification-system. Accessed 22 Jun 2023.

Cohen J (1988) Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Lawrence Erlbaum, Hillsdale

R Core Team (2022) R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing

Kahlenberg CA, Gibbons JAB, Mehta BY, Antao VC, Lai EY, Do HT, Russell LA, Sculco PK, Figgie MP, Goodman SM (2022) Satisfaction with the process vs outcome of care in total hip and knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 37(3):419-424.e2

The Swedish Arthroplasty Register (2023) https://sar.registercentrum.se/. Accessed 12 Apr 2023.

Neginhal V, Kurtz W, Schroeder L (2020) Patient satisfaction, functional outcomes, and survivorship in patients with a customized posterior-stabilized total knee replacement. JBJS Rev 8(7):e1900104

Wendelspiess S, Kaelin R, Vogel N, Rychen T, Arnold MP (2022) No difference in patient-reported satisfaction after 12 months between customised individually made and off-the-shelf total knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 30(9):2948–2957

Zeh A, Gehler V, Gutteck N, Beckmann J, Brill R, Wohlrab D (2021) Superior clinical results and higher satisfaction after customized compared with conventional TKA. Acta Orthop Belg 87(4):649–658

Schroeder L, Dunaway A, Dunaway D (2022) A comparison of clinical outcomes and implant preference of patients with bilateral TKA: one knee with a patient-specific and one knee with an off-the-shelf implant. JBJS Rev 10(2):e20.00182

Young-Shand KL, Dunbar MJ, Laende EK, Mills Flemming JE, Astephen Wilson JL (2021) Early identification of patient satisfaction two years after total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 36:2473–2479

Gandhi R, Mahomed NN, Cram P, Perruccio AV (2018) Understanding the relationship between 3-month and 2-year pain and function scores after total knee arthroplasty for osteoarthritis. J Arthroplasty 33(5):1368–1372

Galea VP, Rojanasopondist P, Connelly JW, Bragdon CR, Huddleston JI, Ingelsrud LH, Malchau H, Troelsen A (2020) Changes in patient satisfaction following total joint arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 35(1):32–38

Symbios (2023) https://symbios.ch/de-ch/medical-professionals/medical-education/programme-de-formation-origin/. Accessed 10 Jun 2023.

Moret CS, Hirschmann MT, Vogel N, Arnold MP (2021) Customised, individually made total knee arthroplasty shows promising 1-year clinical and patient reported outcomes. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 141(12):2217–2225

Ratano S, Müller JH, Daxhelet J, Beckers L, Bondoux L, Tibesku CO, Aït-Si-Selmi T, Bonnin MP (2022) Custom TKA combined with personalised coronal alignment yield improvements that exceed KSS substantial clinical benefits. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 30(9):2958–2965

Gousopoulos L, Dobbelaere A, Ratano S, Bondoux L, ReSurg TCO, Aït-Si-Selmi T, Bonnin MP (2023) Custom total knee arthroplasty combined with personalised alignment grants 94% patient satisfaction at minimum follow-up of 2 years. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 31(4):1276–1283

Daxhelet J, Aït-Si-Selmi T, Müller JH, Saffarini M, Ratano S, Bondoux L, Mihov K, Bonnin MP (2023) Custom TKA enables adequate realignment with minimal ligament release and grants satisfactory outcomes in knees that had prior osteotomies or extra-articular fracture sequelae. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 31(4):1212–1219

Piuzzi NS, Cleveland Clinic O. M. E. Arthroplasty Group (2022) Patient-reported outcomes at 1 and 2 years after total hip and knee arthroplasty: what is the minimum required follow-up? Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 142(9):2121–2129

Schoenmakers DAL, Schotanus MGM, Boonen B, Kort NP (2018) Consistency in patient-reported outcome measures after total knee arthroplasty using patient-specific instrumentation: a 5-year follow-up of 200 consecutive cases. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 26(6):1800–1804

Pronk Y, Pilot P, Brinkman JM, van Heerwaarden RJ, van der Weegen W (2019) Response rate and costs for automated patient-reported outcomes collection alone compared to combined automated and manual collection. J Patient Rep Outcomes 3(1):31

Roos EM, Lohmander LS (2003) The Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS): from joint injury to osteoarthritis. Health Qual Life Outcomes 1:64

Thomsen MG, Latifi R, Kallemose T, Barfod KW, Husted H, Troelsen A (2016) Good validity and reliability of the forgotten joint score in evaluating the outcome of total knee arthroplasty. Acta Orthop 87(3):280–285

Vogel N, Kaelin R, Rychen T, Arnold MP (2022) The German version of the High-Activity Arthroplasty Score is valid and reliable for patients after total knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 30(4):1204–1211

EQ-5D (2021) https://euroqol.org/eq-5d-instruments/eq-5d-3l-about/. Accessed 14 Jan 2021

Scuderi GR, Bourne RB, Noble PC, Benjamin JB, Lonner JH, Scott WN (2012) The New Knee Society Knee Scoring System. Clin Orthop Relat Res 470(1):3–19

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Basel.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Markus Arnold is consultant of ConforMIS. All other authors declare to have no conflict of interest.

Ethical review committee statement

The study was approved by the local ethics committee (ID: 2016-01777) and written informed consent was obtained from all patients in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Vogel, N., Kaelin, R., Rychen, T. et al. Satisfaction after total knee arthroplasty: a prospective matched-pair analysis of patients with customised individually made and off-the-shelf implants. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 31, 5873–5884 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-023-07643-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-023-07643-1