Abstract

Purpose

To determine specific return to sports (RTS) and return to work (RTW) rates of patients with septic arthritis following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction (ACLR), and to assess for factors associated with a diminished postoperative return to physical activity after successful eradication of the infection.

Methods

In this study, patients who were treated for postoperative septic arthritis of the knee following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction between 2006 and 2018 were evaluated at a minimum follow-up (FU) of 2 years. Patients’ outcomes were retrospectively analyzed using standardized patient-reported outcome scores including the Lysholm score and the subjective IKDC score, as well as return to sports and return to work questionnaires to assess for the types, number, and frequency of sports performed pre- and postoperatively and to evaluate for potential occupational changes due to septic arthritis following ACLR. To assess for the signifiance of the graft at follow-up, outcomes were compared between patients with a functioning graft at FU and those without, as well as between patients with initial graft retention and those with graft removal and consecutive revision ACLR.

Results

Out of 44 patients eligible for inclusion, 38 (86%) patients at a mean age of 36.2 ± 10.3 years were enrolled in this study. At a mean follow-up of 60.3 ± 39.9 months, the Lysholm score and the subjective IKDC score reached 80.0 ± 15.1 and 78.2 ± 16.6 points, respectively. The presence of a graft at FU yielded statistically superior results only on the IKDC score (p = 0.014). There were no statistically significant differences on the Lysholm score (n.s.) or on the IKDC score (n.s.) between patients with initial graft retention and those with initial removal who had undergone revision ACLR. All of the included 38 patients were able to return to sports at a median time of 8 (6–16) months after their last surgical intervention. Among patients who performed pivoting sports prior to their injury, 23 (62.2%) returned to at least one pivoting sport postoperatively. Overall, ten patients (26.3%) returned to all their previous sports at their previous frequency. The presence of a graft at FU resulted in a significantly higher RTS rate (p = 0.010). Comparing patients with initial graft retention and those with graft removal and consecutive revision ACLR, there was no statistically significant difference concerning the RTS rate (n.s.). Thirty-one patients (83.8%) were able to return to their previous work.

Conclusion

Successful eradication of septic arthritis following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction allows for a postoperative return to sports and a return to work particularly among patients with ACL-sufficient knees. However, the patients’ expectations should be managed carefully, as overall return rates at the pre-injury frequency are relatively low.

Level of evidence

IV.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In recent years, the understanding of correctly diagnosing and treating septic arthritis (SA) of the knee following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction (ACLR) has steadily increased [6, 7, 23, 27, 28, 35, 41, 43]. Particularly, graft retaining protocols emphasizing the combination of antibiotic regimen and surgical management have led to favorable postoperative objective results and satisfying patient-reported outcomes [10, 16, 21, 34, 47]. But while many conventional patient-reported outcome scores as well as laxity measurements have demonstrated their importance, particularly in a scientific setting, such assessments are often abstract at the individual level [3]. Meanwhile important personal aspects for patients, such as a successful athletic and occupational rehabilitation after this severe complication, have gained little attention in the previous literature [8, 29, 32]. Yet as patients affected by septic arthritis following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction tend to be young and active, more thorough information about prognoses of postoperative activity levels as well as impacts on the professional lives is crucial. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to evaluate the return to sports (RTS) and return to work (RTW) rates after septic arthritis following ACLR at a medium- to long-term follow-up and to assess for factors associated with diminished postoperative return to sports and return to work rates after successful eradication of septic arthritis. Our primary hypothesis was that patients with a graft sufficient knee at follow-up would be able to return to sports and work at higher rates compared to patients with graft insufficient knees. Furthermore, it was hypothesized that among patients with a graft sufficient knee at follow-up, initial graft retention would prove beneficial with respect to clinical outcomes compared to initial graft removal and consecutive ACLR revision.

Materials and methods

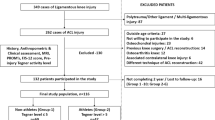

A monocentric Institutional Review Board approved Level IV retrospective case series was conducted (institution blinded for review, permit number 279/20 S-SR) and written informed consent was obtained from each patient before participation. Patients who underwent open or arthroscopic treatment for septic arthritis following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction at the main author’s institution between 01/2006 and 12/2018 with a minimum follow-up of 24 months after their last treatment of septic arthritis were eligible for this study. Patients were included both in cases of graft retention and graft removal during the treatment of their septic arthritis. Patients were excluded if they were non-residents or if they had undergone concomitant (osteo)chondral transplantation, mechanical alignment correction, or multi-ligament surgery during index ACLR. Eligible patients were contacted via mail and were considered lost to follow-up if they refused to participate or failed to respond to the mailed survey. Baseline demographics (e.g., sex, age, operated side) were gathered from medical records and operative information on the type of index ACLR (primary vs. revision), concomitant procedures during index surgery, graft type, operative technique (single bundle vs. double bundle), staging according to Gaechter classification [50], and microorganisms causative for infection were obtained from the clinic records for all patients. The procedure (primary or revision ACLR) which preceded the onset of septic arthritis was considered as the index ACLR.

Diagnosis and treatment of postoperative septic arthritis

The diagnostic algorithm and treatment regimen applied for suspected cases of septic arthritis has previously been published by this group [37]. In summary, the diagnosis of septic arthritis after ACLR was obtained based on clinical manifestations (e.g., pain, joint swelling, local erythema, hyperthermia, and purulent secretion), laboratory results (e.g., C-reactive protein > 0.5 mg/dl, white blood cell count > 10,000/ µl), and microbiologic findings from a joint aspirate or tissue gathered during arthroscopy. Grading was based on arthroscopic findings according to the Gaechter classification [50].

The standard of care for treatment of septic arthritis following ACLR includes a combination of systemic antibiotics in addition to surgical irrigation and debridement. A calculated antibiotic treatment regime is initiated and adapted based on pathogen sensitivity testing and the patient’s prior history of antibiotic resistance. Usually, an initial intravenous therapy for 10–14 days followed by a period of at least four weeks of oral antibiotics is utilized and thus was used in this study. Arthroscopic irrigation and debridement (I&D) was performed in every suspected or confirmed case of septic arthritis, and performed repeatedly, if necessary, until negativity of microbiological cultures was sustained after 48 h. Conversion to an open revision was reserved for severe cases of septic arthritis (Gaechter IV) or in cases of unsuccessful arthroscopic I&D. Grafts were salvaged unless they showed signs of insufficiency in arthroscopic testing or osteomyelitis involving the bone tunnels used for anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) fixation, as well as in cases of persistent infection despite repeated I&D. Suction drains were placed intraoperatively and removed after drainage had ceased, usually around the third postoperative day. Patients were restricted to bed rest for 48 h postoperatively, with consecutive partial weight bearing for the first two weeks after treatment. Eradication of septic arthritis was considered successful after a complete cease of clinical and laboratory signs of infection including negativity of all microbiologic cultures.

Outcome measures

Clinical outcomes were evaluated at a minimum of two years after the last surgical treatment for septic arthritis and included the Lysholm score and the subjective knee evaluation form administered by the International Knee Documentation Committee (IKDC). To assess for a minimal clinically important difference (MCID), a difference of 10 points and of 9 points were used for the Lysholm score and the IKDC scores, respectively [31]. Additionally, a return to sports and return to work questionnaire was developed, as no validated return to sports questionnaire exists for septic arthritis following ACLR. This form was based on questionnaires used in previous studies about postoperative sporting activities and adjusted for our study population [14]. The questionnaire was divided into three parts. The first part contained information about the patients’ medical and surgical history before and after the treatment of septic arthritis at our institution, overall postoperative satisfaction (very satisfied, partially satisfied, barely satisfied, and not satisfied), and persisting complaints in the ipsilateral knee (instability, pain, stiffness, other). The second part of the questionnaire assessed types, number, and frequency of sports or activities carried out for at least six months prior to the injury leading to the index surgery, as well as types, number, and frequency at the time of follow-up. Types of sports were categorized dichotomously into pivoting sports and non-pivoting sports [18]. Frequency was categorized as low (a maximum of 30–60 min per week), medium (up to 60 min at least 2–3 times per week), and high (at least 60 min and greater than 3 times per week). Furthermore, the time to full return to sports, postoperative reduction of frequency, or the discontinuation of any sports previously performed was evaluated. Return to sports was defined as the postoperative performance of any type of sports carried out at least 30–60 min per week. Return to the previous level of sports was considered to be the continuation of all sports at the same frequency as before the index surgery. Reasons for discontinuation of any sports or for the reduction of frequency of sports were further evaluated (ipsilateral knee instability, pain, stiffness, fear of re-injury, other). The third part of the questionnaire collected information on occupational behaviors and employment. The level of employment was assessed according to various activities carried out during work (e.g., sitting, standing, lifting, and carrying) [13, 45]. These levels were then categorized dichotomously into sedentary labor and non-sedentary/physical labor based on the intensity and duration of the work activities.

To assess for the significance of a graft and its characteristics (initial graft salvage vs. initial graft removal with or without consecutive revision ACLR), follow-up outcome scores and return rates were compared between patients with graft sufficient knees (presence of a graft at follow-up) and those without (no graft at follow-up), as well as between patients with initial graft retention and those with initial graft removal and consecutive ACLR revision. Further variables including age (> 30 years vs. < 30 years), sex, surgical technique used for index ACLR, revision status for index ACLR, concomitant injuries, and microorganisms causative for infection were analyzed regarding their effect on postoperative outcomes.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis for this study was performed using the SPSS Software version 26 (IBM, statistics). Distribution of the variables was assessed using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Continuous non-parametric variables are presented as median (1st quartile–3rd quartile) and parametric data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. Absolute numbers and percentages were used for categorial variables. The Mann–Whitney U test was applied for comparison of continuous non-parametric values and the Chi-square test was used for comparison of categorial variables. All p values were calculated two-tailed and the level for statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. To assess for the statistical power of this study, a post hoc power analysis was performed for outcome comparison of the IKDC score between patients with graft removal and graft retention using two-tailed tests. It was shown that the required sample size of 38 could achieve an adequate power of 0.90 with an alpha of 0.05 using G*Power (version 3.1.9, Düsseldorf) [11].

Results

Baseline demographics

Between 2006 and 2018, 57 patients underwent surgical treatment for septic arthritis following ACLR at a single institution. Thirteen patients were excluded due to a nonresident status or because of reconstructive concomitant procedures. Six (14%) of the remaining 44 patients eligible for inclusion were lost to follow-up. Thus, a total of 38 patients (86%) were included in the final analysis. Demographic and surgical data of the included patients are presented in Table 1.

Patient-reported outcomes

Follow-up scores were available for all 38 patients. The total Lysholm score and subjective IKDC score of the included patients reached a mean of 80.0 ± 15.1 and 78.2 ± 16.6 points after 60.3 ± 39.9 months. Overall, 32 patients (84.2%) were either very satisfied (n = 18; 47.4%) or satisfied (n = 14; 36.8%) with their postoperative results. Six patients (15.8%) were either barely satisfied (n = 3; 7.9%) or not satisfied (n = 3; 7.9%). Postoperative patient satisfaction was associated with superior results both on the Lysholm score (p = 0.007) and the subjective IKDC score (p = 0.002). Subgroup comparisons of the outcome scores with respect to graft characteristics are listed in Table 2.

Patients’ age and sex, the surgical technique used for index ACLR (single bundle vs. double bundle), the presence of concomitant injuries, or the microorganisms found (coagulase negative staphylococci vs. Staphylococcus aureus) did not significantly affect the Lysholm score (n.s.) or the IKDC score (n.s.) at follow-up. Thirty-one patients (81.6%) reported persisting complaints regarding the operated knee. Pain was most frequently reported (n = 20; 52.6%), followed by a decreased range of motion and instability (n = 13; 34.2%). Seven patients (18.4%) reported no persisting issues at final follow-up.

Postoperative return to sports

All 38 patients included in this study reported to have participated in sports on a regular basis within six months of their index ACL injury. Prior to their injuries, two patients (5.4%) reported to have engaged in sports at a low frequency, twenty-three patients (62.2%) at a medium frequency, and eleven patients (28.9%) at a high frequency.

At a mean follow-up of 99.3 ± 29.7 months, all patients reported to have returned to sports at a median duration of 8 months (6–16 months) after their last treatment for septic arthritis. Twenty-one patients (55.3%) had discontinued at least one sport because of their injured knee. Figure 1 displays the activities and rates of the sports performed pre- and postoperatively.

Of the sports discontinued, all sports were pivoting sports (Table 3). Eighteen patients (51.4%) reported a reduction of frequency compared to their preinjury status. Overall, ten patients (26.3%) reported to have returned to all their preinjury sports at their preinjury frequency at follow-up. Reasons for discontinuation of any sport are listed in Table 4.

The only factor significantly associated with diminished postoperative return to sports was the lack of a graft at final follow-up (p = 0.010), while the graft characteristic (initial graft salvage vs. initial graft removal with consecutive ACLR revision) did not significantly affect return to sports rates (n.s.). A detailed list of the main activities specific subgroups of patients returned to is provided in the Supplementary Appendix.

Postoperative return to work

Return to work data was available for 37 patients. All patients were either employed or students at an educational institution at time of diagnosis of their septic arthritis. Overall, twenty patients (54.1%) had a sedentary occupation, and seventeen patients (45.9%) had a non-sedentary/physical occupation. Six of the patients (16.2%) had to either transfer to lower the intensity work within their job or change jobs entirely due to the implications of their injury, while thirty-one (83.8%) continued at the same level of intensity within their previous occupation. Of the six patients who had to change jobs or transfer within their workplace, four (66.7%) carried out a non-sedentary/physical occupation preoperatively and two patients (33.3%) worked in a sedentary job. There was no association between the ability of patients to return to sports and to return to work (n.s.).

Discussion

The main finding of this study was that successful treatment of septic arthritis after ACLR enabled patients to return to sports, even though return rates to all sports at the previous frequency were diminished. Furthermore, all patients returned to work and most of them returned to their pre-injury occupation. In accordance with our primary hypothesis, the presence of a graft at follow-up was advantageous for return to sports. Yet, this was true regardless of the graft characteristic (initial salvage vs. graft removal with consecutive revision ACLR), thus rejecting our secondary hypothesis.

To our knowledge, this is the largest study on postoperative patient outcomes after septic arthritis following ACLR to date and the first one to evaluate the return to sports and return to work rates of these patients in detail. In our study, all 38 patients successfully returned to any sports after treatment of septic arthritis, and of the 37 patients who had performed pivoting sports prior to their injury, almost two-thirds (62.2%) restarted a pivoting sport postoperatively. There was a trend for a higher return to pivoting sports among patients under the age of 30, but regardless of age, highest return to sport rates were seen in typical endurance and low demand activities with little risk of (re-)injury (e.g., swimming, running, and cycling). The overall return rate to all previous sports at the pre-injury frequency was relatively low at 26.3%.

Recent advances in the prevention of postoperative septic arthritis after ACLR, namely different methods of perioperative antibiotic graft soaking, have raised hopes to efficiently reduce infection rates, likely without relevant adverse effects on the graft [4, 12, 24, 30, 33, 36, 42, 51]. Nonetheless, concerns remain regarding this practice among surgeons, and septic arthritis continues to pose a threat to patients’ outcomes [47, 52]. Besides traditional outcome measures including patient-oriented outcome forms and laxity testing, participation-based parameters such as return to sports and return to work can help to clarify the impact of this condition on patients’ lives and assist in guiding postoperative expectations [38, 44, 46]. But in the current literature, return to sports rates after SA following ACLR are heterogeneous, ranging between 50 and 100%, often lacking specification regarding the types or levels of sports performed, and therefore render detailed advice difficult [1, 5, 8, 22, 28].

In two case–control studies, Abdel-Azis et al. [1] and Bostrom Windhamre et al. [7], found a return to (recreational) activities in 56% and 62.5% of their patients without further stating the types or characteristics of the sports. Binnet et al. [5] reported a return to previous level in competitive sports in one out of three patients, but with a limited sample size (n = 6). Similar to our findings, Calvo et al. [8] and Monaco et al. [29] reported a full return to athletic activity in their studies in all seven and all 14 patients, respectively. However, the authors describe higher return rates to a preinjury level of activity compared to our study (85.7% and 78.6%, respectively). Interestingly, the authors point out the importance of initial graft retention for a return to sports. While there is evidence that initial graft removal is associated with inferior postoperative subjective and objective outcomes (particularly without consecutive ACLR revision) [15, 37], we were not able to find an association between initial graft removal and lower return to sports rates. This is in concordance with findings by Waterman et al.[48], who found no correlation between initial graft removal during the treatment of SA and a postoperative return to active military duty. In our study, persistent ACL deficiency at follow-up was the only patient-dependent factor significantly associated with an inferior RTS rate, which is consistent with the findings of previous studies, showing an association of ACL deficiency after treatment for SA and diminished Tegner activity scores [15, 41]. Patients in this study, who underwent initial graft removal and consecutive ACLR revision reached similar RTS rates as patients with initial graft retention. Therefore, it is likely that it is the presence of a graft that matters, not whether it is a primary or revision graft, even though negative implication on return rates may remain in either case. But implications on return to sports rates are also seen in patients who undergo ACLR without postoperative septic arthritis [3, 53]. In their systematic review, Ardern et al.[3] found a mean return to any type of sports of 82%, and a return to previous level of activity of 63% after ACLR at 44 months. In a later case series, the same authors reported a return to preinjury level of sports of 44.6% after a mean of 39 months[2]. Similar results are reported by Grassi et al.[17], who in their systematic review on postoperative outcomes after revision ACLR report a RTS rate of 85%, and a return to preinjury level of sports of 53% after 4.2 years.

As to why patients do not return to sports, patient-associated factors, such as gender and the level of sports performed preoperatively, have to be considered as well as structural and functional deficits of the injured knee [39, 40], which is highlighted by the fact, that about 80% of the patients in this study reported persisting issues with their operated knee. But interestingly, only about half of the patients who reported to have stopped any sports in this study did so because of the operated knee, indicating that additional aspects may be of relevance. There is increasing awareness of the impact of psychological factors such as a lack of motivation, fear of re-injury, or a shift of interests on patients’ capability to return to activity postoperatively [9, 15, 25, 28, 41]. The effect of these so-called ‘soft factors’ might also explain the discrepancies often found between solid clinical outcome parameters and diminished return to sports rates found in our study and in the literature [13, 14, 20, 49]. For example, in our study, fear of re-injury was the most frequently given answer for the discontinuation of a sport. While this aspect has previously been highlighted regarding patients after ACLR without postoperative complications, the repercussions may be of even greater relevance in patients who have suffered from a condition as complicated and disabling as septic arthritis [3, 26, 38].

Despite the high relevance for patients to be able to work after a surgery, particularly among young patients, there remains a scarcity of studies investigating postoperative return to work rates. In our study, all patients were able to return to work after successful eradication of infection. As expected, patients with physical demanding occupations were affected more often as evidenced by a change of job or transfer to a lower intensity work within their job. This finding is intuitive and consistent with results presented by Groot et al. [19] who describe a return to work rate of 92% (n = 82) after ACLR, with the highest rates of return to employment among patients in initially sedentary jobs.

While this study does demonstrate important findings, it is not without limitations. From a methodological point of view, we point out that this was a retrospective monocentric study. Therefore, the lack of randomization inherent to this study design bears an increased risk for selection bias. However, regarding demographic and surgical aspects, the cohort of this study well reflects collectives described in the literature [28]. Also, the RTS questionnaire used in this study was a non-standardized questionnaire with a potential question order bias. Yet, our questionnaire was based on previously published protocols to attempt to standardize and reduce the risk of bias [13, 14]. Finally, retrospective studies involve a risk for recall bias. But the key parameters assessed in this study (return to sports and return to work) are ongoing variables, ideally still being true at the time of the follow-up and thus reducing the risk for recall bias with respect to these key parameters. Also, as patient outcomes were assessed in an intention to treat fashion, revision surgeries after eradication of septic arthritis might have confounded the results. However, as these revision surgeries were few and as we intended to give an adequate representation of all patients with septic arthritis following ACLR, including the potential revisions, all patients were included for final analysis.

Finally, while septic arthritis following ACLR remains an infrequent complication, it may come with repercussions on patients’ physical activity and professional life. While no clear activity recommendations can be drawn from our data, this study is intended to raise awareness of the factors associated with diminished return to sports and work rates and to help clinical practitioners guide their patients’ expectations in these situations.

Conclusion

Patients who undergo successful treatment of septic arthritis following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction can return to both low and to high demand sports, with highest return rates seen for typical endurance sports. Yet, a return to preinjury sports at a preinjury level among these patients is relatively low. ACL deficiency at follow-up is predictive of inferior subjective outcome scores and leads to a decreased likelihood of returning to preinjury sports. Finally, successful eradication of septic arthritis allows for a substantial return to previous work.

Abbreviations

- SA:

-

Septic arthritis

- ACLR:

-

Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction

- RTS:

-

Return to sports

- I&Ds:

-

Irrigations and debridements

- ACL:

-

Anterior cruciate ligament

- IKDC:

-

International Knee Documentation Committee

- MCID:

-

Minimal clinically important difference

- HS:

-

Hamstring

- SB:

-

Single bundle

- DB:

-

Double bundle

- PROMs:

-

Patient-reported outcome measures

References

Abdel-Aziz A, Radwan YA, Rizk A (2014) Multiple arthroscopic debridement and graft retention in septic knee arthritis after ACL reconstruction: a prospective case–control study. Int Orthop 38:73–82

Ardern CL, Taylor NF, Feller JA, Webster KE (2012) Return-to-sport outcomes at 2 to 7 years after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery. Am J Sports Med 40:41–48

Ardern CL, Webster KE, Taylor NF, Feller JA (2011) Return to sport following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the state of play. Br J Sports Med 45:596–606

Banios K, Komnos GA, Raoulis V, Bareka M, Chalatsis G, Hantes ME (2021) Soaking of autografts with vancomycin is highly effective on preventing postoperative septic arthritis in patients undergoing ACL reconstruction with hamstrings autografts. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 29:876–880

Binnet MS, Basarir K (2007) Risk and outcome of infection after different arthroscopic anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction techniques. Arthroscopy 23:862–868

Bohu Y, Klouche S, Herman S, de Pamphilis O, Gerometta A, Lefevre N (2019) Professional athletes are not at a higher risk of infections after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: incidence of septic arthritis, additional costs, and clinical outcomes from the French Prospective Anterior Cruciate Ligament Study (FAST) cohort. Am J Sports Med 47:104–111

Bostrom Windhamre H, Mikkelsen C, Forssblad M, Willberg L (2014) Postoperative septic arthritis after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: does it affect the outcome? A retrospective controlled study. Arthroscopy 30:1100–1109

Calvo R, Figueroa D, Anastasiadis T, Vaisman A, Olid A, Gili F et al (2014) Septic arthritis in ACL reconstruction surgery with hamstring autografts. Eleven years of experience. Knee 21:717–720

Czuppon S, Racette BA, Klein SE, Harris-Hayes M (2014) Variables associated with return to sport following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a systematic review. Br J Sports Med 48:356–364

Ekdahl V, Stålman A, Forssblad M, Samuelsson K, Edman G, Kraus Schmitz J (2020) There is no general use of thromboprophylaxis and prolonged antibiotic prophylaxis in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a nation-wide survey of ACL surgeons in Sweden. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 28:2535–2542

Faul F, Erdfelder E, Buchner A, Lang AG (2009) Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav Res Methods 41:1149–1160

Figueroa D, Figueroa F, Calvo R, Lopez M, Goñi I (2019) Presoaking of hamstring autografts in vancomycin decreases the occurrence of infection following primary anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Orthop J Sports Med 7:2325967119871038

Garcia GH, Mahony GT, Fabricant PD, Wu HH, Dines DM, Warren RF et al (2016) Sports- and work-related outcomes after shoulder hemiarthroplasty. Am J Sports Med 44:490–496

Garcia GH, Taylor SA, DePalma BJ, Mahony GT, Grawe BM, Nguyen J et al (2015) Patient activity levels after reverse total shoulder arthroplasty: what are patients doing? Am J Sports Med 43:2816–2821

Gille J, Gerlach U, Oheim R, Hintze T, Himpe B, Schultz AP (2015) Functional outcome of septic arthritis after anterior cruciate ligament surgery. Int Orthop 39:1195–1201

Gobbi A, Karnatzikos G, Chaurasia S, Abhishek M, Bulgherhoni E, Lane J (2016) Postoperative infection after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Sports Health 8:187–189

Grassi A, Zaffagnini S, Marcheggiani Muccioli GM, Neri MP, Della Villa S, Marcacci M (2015) After revision anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction, who returns to sport? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med 49:1295–1304

Grindem H, Eitzen I, Moksnes H, Snyder-Mackler L, Risberg MA (2012) A pair-matched comparison of return to pivoting sports at 1 year in anterior cruciate ligament-injured patients after a nonoperative versus an operative treatment course. Am J Sports Med 40:2509–2516

Groot JA, Jonkers FJ, Kievit AJ, Kuijer PP, Hoozemans MJ (2017) Beneficial and limiting factors for return to work following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a retrospective cohort study. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 137:155–166

Hoorntje A, Kuijer P, van Ginneken BT, Koenraadt KLM, van Geenen RCI, Kerkhoffs G et al (2019) Prognostic factors for return to sport after high tibial osteotomy: a directed acyclic graph approach. Am J Sports Med 47:1854–1862

Jefferies JG, Aithie JMS, Spencer SJ (2019) Vancomycin-soaked wrapping of harvested hamstring tendons during anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. A review of the ‘vancomycin wrap; Knee 26:524–529

Judd D, Bottoni C, Kim D, Burke M, Hooker S (2006) Infections following arthroscopic anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Arthroscopy 22:375–384

Kraus Schmitz J, Lindgren V, Edman G, Janarv PM, Forssblad M, Stålman A (2021) Risk factors for septic arthritis after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a nationwide analysis of 26,014 ACL reconstructions. Am J Sports Med 49:1769–1776

Kusnezov N, Eisenstein ED, Dunn JC, Wey AJ, Peterson DR, Waterman BR (2018) Anterior cruciate ligament graft removal versus retention in the setting of septic arthritis after reconstruction: a systematic review and expected value decision analysis. Arthroscopy 34:967–975

Lai CCH, Ardern CL, Feller JA, Webster KE (2018) Eighty-three per cent of elite athletes return to preinjury sport after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a systematic review with meta-analysis of return to sport rates, graft rupture rates and performance outcomes. Br J Sports Med 52:128–138

Langford JL, Webster KE, Feller JA (2009) A prospective longitudinal study to assess psychological changes following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery. Br J Sports Med 43:377–381

Lo Presti M, Costa GG, Grassi A, Cialdella S, Agrò G, Busacca M et al (2020) Graft-preserving arthroscopic debridement with hardware removal is effective for septic arthritis after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a clinical, arthrometric, and magnetic resonance imaging evaluation. Am J Sports Med 48:1907–1915

Makhni EC, Steinhaus ME, Mehran N, Schulz BS, Ahmad CS (2015) Functional outcome and graft retention in patients with septic arthritis after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a systematic review. Arthroscopy 31:1392–1401

Monaco E, Maestri B, Vadala A, Iorio R, Ferretti A (2010) Return to sports activity after postoperative septic arthritis in ACL reconstruction. Phys Sports Med 38:69–76

Naendrup JH, Marche B, de Sa D, Koenen P, Otchwemah R, Wafaisade A et al (2020) Vancomycin-soaking of the graft reduces the incidence of septic arthritis following ACL reconstruction: results of a systematic review and meta-analysis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 28:1005–1013

Nwachukwu BU, Chang B, Voleti PB, Berkanish P, Cohn MR, Altchek DW et al (2017) Preoperative short form health survey score is predictive of return to play and minimal clinically important difference at a minimum 2-year follow-up after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med 45:2784–2790

Nwachukwu BU, Voleti PB, Berkanish P, Chang B, Cohn MR, Williams RJ 3rd et al (2017) Return to play and patient satisfaction after acl reconstruction: study with minimum 2-year follow-up. J Bone Jt Surg Am 99:720–725

Offerhaus C, Balke M, Hente J, Gehling M, Blendl S, Höher J (2019) Vancomycin pre-soaking of the graft reduces postoperative infection rate without increasing risk of graft failure and arthrofibrosis in ACL reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 27:3014–3021

Pérez-Prieto D, Perelli S, Corcoll F, Rojas G, Montiel V, Monllau JC (2021) The vancomycin soaking technique: no differences in autograft re-rupture rate. A comparative study. Int Orthop 45:1407–1411

Pérez-Prieto D, Portillo ME, Torres-Claramunt R, Pelfort X, Hinarejos P, Monllau JC (2018) Contamination occurs during ACL graft harvesting and manipulation, but it can be easily eradicated. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 26:558–562

Phegan M, Grayson JE, Vertullo CJ (2016) No infections in 1300 anterior cruciate ligament reconstructions with vancomycin pre-soaking of hamstring grafts. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 24:2729–2735

Pogorzelski J, Themessl A, Achtnich A, Fritz EM, Wortler K, Imhoff AB et al (2018) Septic Arthritis after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: how important is graft salvage? Am J Sports Med 46:2376–2383

Ross MD, Irrgang JJ, Denegar CR, McCloy CM, Unangst ET (2002) The relationship between participation restrictions and selected clinical measures following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 10:10–19

Rousseau R, Labruyere C, Kajetanek C, Deschamps O, Makridis KG, Djian P (2019) Complications after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction and their relation to the type of graft: a prospective study of 958 cases. Am J Sports Med 47:2543–2549

Salmon L, Russell V, Musgrove T, Pinczewski L, Refshauge K (2005) Incidence and risk factors for graft rupture and contralateral rupture after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Arthroscopy 21:948–957

Schulz AP, Gotze S, Schmidt HG, Jurgens C, Faschingbauer M (2007) Septic arthritis of the knee after anterior cruciate ligament surgery: a stage-adapted treatment regimen. Am J Sports Med 35:1064–1069

Schuster P, Schlumberger M, Mayer P, Eichinger M, Geßlein M, Richter J (2020) Soaking of autografts in vancomycin is highly effective in preventing postoperative septic arthritis after revision anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 28:1154–1158

Schuster P, Schlumberger M, Mayer P, Raoulis VA, Oremek D, Eichinger M et al (2020) Lower incidence of post-operative septic arthritis following revision anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with quadriceps tendon compared to hamstring tendons. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 28:2572–2577

Stucki G (2005) International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF): a promising framework and classification for rehabilitation medicine. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 84:733–740

US Department of Labor OoALJ. Dictionary of Occupational Titles (DOT). Revised 4th edn. http://www.oalj.dol.gov/PUBLIC/DOT/REFERENCES/DOTAPPC.HTM. Accessed 4 June 2019

van Brakel WH, Anderson AM, Mutatkar RK, Bakirtzief Z, Nicholls PG, Raju MS et al (2006) The Participation Scale: measuring a key concept in public health. Disabil Rehabil 28:193–203

Wang C, Lee YH, Siebold R (2014) Recommendations for the management of septic arthritis after ACL reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 22:2136–2144

Waterman BR, Arroyo W, Cotter EJ, Zacchilli MA, Garcia ESJ, Owens BD (2018) Septic arthritis after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: clinical and functional outcomes based on graft retention or removal. Orthop J Sports Med 6:2325967118758626

Weiss JM, Noble PC, Conditt MA, Kohl HW, Roberts S, Cook KF et al (2002) What functional activities are important to patients with knee replacements? Clin Orthop Relat Res 404:172–188

Widmer AF, Gaechter A, Ochsner PE, Zimmerli W (1992) Antimicrobial treatment of orthopedic implant-related infections with rifampin combinations. Clin Infect Dis 14:1251–1253

Xiao M, Leonardi EA, Sharpe O, Sherman SL, Safran MR, Robinson WH et al (2020) Soaking of autologous tendon grafts in vancomycin before implantation does not lead to tenocyte cytotoxicity. Am J Sports Med 48:3081–3086

Xiao M, Sherman SL, Safran MR, Abrams GD (2021) Surgeon practice patterns for pre-soaking ACL tendon grafts in vancomycin: a survey of the ACL study group. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 29:1920–1926

Zaffagnini S, Grassi A, Serra M, Marcacci M (2015) Return to sport after ACL reconstruction: how, when and why? A narrative review of current evidence. Joints 3:25–30

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. There was no financial conflict of interest with regards to this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All listed authors have contributed substantially to this work: AT, JP, SB, ABI engaged in the study conception and design; AT and JP performed the data collection; AT and MCR performed the data analysis; AT, JP, SB, and ABI performed the data interpretation; AT, FM, MCR and KH drafted the manuscript and the figures, and performed the literature research; AT, MCR, KH, JP, SB and ABI critically revised the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Andreas B. Imhoff receives royalties from Arthrex Inc. (Naples, FL, USA) and Arthrosurface (Franklin, MA). He is a consultant for Arthrosurface (Franklin, MA, USA) and medi (Bayreuth, Germany). Stefan Buchmann is a consultant for Arthrex Inc. (Naples, FL, USA) and Truetape (Munich, Germany). The companies were not involved in the study design, data collection, or final manuscript.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the Technical University Munich (permit number 279/20 S-SR). All procedures performed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Themessl, A., Mayr, F., Hatter, K. et al. Patients return to sports and to work after successful treatment of septic arthritis following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 30, 1871–1879 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-021-06819-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-021-06819-x