Abstract

Purpose

Describe the motivation for floorball participation, injury prevention expectations, injury risk perceptions and prevalence of health problems in youth floorball players at the start of the season.

Methods

This cross-sectional survey is part of a larger Sport Without Injury ProgrammE (SWIPE) project and provides baseline data before a cluster randomised controlled trial of an injury prevention program (Knee Control). A baseline survey (online and paper based) was collected from 47 teams with 471 youth floorball players from two provinces of Sweden before the start of the 2017 season.

Results

The mean age for 140 females and 331 males was 13.7 (± 1.5) and 13.3 (± 1.0) years, respectively. The two most significant motivators for floorball participation were being part of the team (82% females, 75% males) and friends (65% females, 70% males). Fractures (84% females, 90% males), eye injuries (90% females, 83% males) and concussion (82% females, 83% males) were perceived as the most severe injuries. 93% of players believed that sports injuries can be prevented, while 74% believed it is unlikely that they will sustain an injury. Existing health problems at the beginning of the season were prevalent in 33% of players, with 65% being injuries and 35% illnesses. 17% of existing injuries at the start of the season caused time-loss from play and 17% required medical attention.

Conclusion

Social aspects were the greatest motivators for floorball participation in youths, suggesting that these factors are important to retain sports participants. The high number of health problems in youth is a concern; as such more effort, resources and priority should be given to sports safety programs. Many players believed that sports injuries can be prevented, possibly providing a fertile ground for implementation of such programs.

Level of evidence

IV.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The popularity of floorball is increasing globally, and the International Floorball Federation, which is a full member of the International Olympic Committee, has 68 member countries [11]. Floorball is one of the most popular sports in Sweden, with approximately 124,000 licensed players (81% are under 19 years old, and of these, 24% are female) registered with the Swedish Floorball Federation [11]. Floorball is a non-contact sport played indoors with a light hollow plastic ball and a graphite compound stick. A typical game involves three 20-min periods with two 10-min intermissions, though children and youth often play three 15-min periods. Each team is composed of five players and a goalkeeper. Similar to other pivoting sports, floorball involves sudden acceleration/deceleration, stops, and sharp changes of direction on a hard-playing surface and therefore involves a high risk of injury to the lower limb [18, 22]. For example, at the elite level, most injuries involve joints or ligaments, with predominantly ankle and knee injuries, including anterior cruciate ligament injuries [18, 22]. The incidence of non-contact injuries to the lower limb was reduced when using a neuromuscular training programme in adult elite female floorball players [19].

Despite the increased popularity of floorball in youth athletes, much of the available research regarding injuries in floorball focuses on elite athletes or adults. Injury panorama and injury risk factors and injury mechanisms may be different between youth and adults owing to the physiological differences between these groups, including muscle function, physical development, and differences in joint kinematics, skill levels and workloads. As such, the available evidence relating to adult elite athletes cannot necessarily be extended to youth players.

The risk of injury may also impact sports participation. Sports and sporting clubs provide opportunities and settings for people to be active and live a healthy lifestyle; this is particularly important given that inactivity is a significant current public health concern [4, 9]. Close social relationships (particularly parents and peer relationships), friendship quality, fitness and health, competence, sports events, enjoyment and relaxation through sports have been identified as motivators for youth athletes to continue participating in sports [12, 23]. However, the motivation for sports participation significantly varied between sexes, where popularity was a stronger motivation for sports participation in males than females [12]. Currently, no study has investigated motivators for participation in floorball among youth players. Such information is important for the governing sport bodies in order to embed strategies to sustain participants. This study aims to be the first to investigate motivation for floorball participation, injury prevention expectations, injury risk perceptions and prevalence of health problems in youth floorball players at the start of the season.

Materials and methods

This cross-sectional survey is part of a larger Sport Without Injury ProgrammE (SWIPE) project and provides baseline data before a cluster randomised controlled efficacy trial of an injury prevention program (Knee Control). Inclusion criteria were youth floorball players aged 12–17 years who were registered to play floorball at a club in two provinces of Southern Sweden (Östergötland and Småland) for the 2017–2018 season. Included teams should not have used the Knee Control injury prevention exercise program, or similar structured injury prevention exercise program, in the last year; and should train at least twice a week to obtain an adequate dose of the training intervention. Study participant recruitment is illustrated in Fig. 1. A survey was distributed in paper-based and online forms to all participating youth floorball teams before the start of the season in October 2017. Two reminders were sent to non-responders (players) and one reminder to coaches of these teams via email and SMS.

The baseline survey included 20 questions relating to player demographic characteristics, sports participation, injury prevention expectations and injury risk perceptions (Table 1). For example, a seven-point Likert scale was used for the question relating to motivation for sports participation. For the analysis responses of 1–3 were grouped as low significance, 4 was considered neutral and 5–7 were grouped as high significance. The same seven-point Likert scale and grouping strategy was used for questions relating to perception of injury risk and injury severity.

To collect baseline health problem data, all players completed the Oslo Sports Trauma Research Center (OSTRC) questionnaire on health problems [7] and overuse injury questionnaire [6] at the beginning of the season. Each question response is marked with between 0 and 25 points where 0 represented no health problem and 25 was a severe problem (Table 1). The scores were summed to calculate the OSTRC severity score (range 0–100), and a score of ≥ 40 was considered as a severe health problem.

This study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Linköping (Project number Dnr 2017/294-31).

Statistical analysis

Data were analysed using SPSS® 25.0 (IBM SPSS Statistics 2015), and descriptive statistics were used to motivation for floorball participation, injury prevention expectations, injury risk perception and reported health problems. As the data were non-normally distributed, a Mann–Whitney U test was conducted to compare differences between two independent groups. A P value of ≤ 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Survey respondents’ characteristics

In total, 471 players were included in this pre-season survey. The study participants (Table 2) were 140 females (mean age 13.7 ± 1.5 years) and 331 males (mean age 13.3 ± 1.0 years). Of the female participants, 62% (n = 93) had menarche. On average, the youth had played floorball for 4.9 ± 2.3 years. Most youth (65%, n = 291) also played other sports, and a majority of these (76%, n = 218) played football. Also, 17% (n = 80) of the youth attended a school with sports specialisation, and 7% (n = 34) were at a school with floorball specialisation. Most youth (51% of females and 55% of males) trained and played floorball three times per week in their teams, and the majority of players (69% of females and 76% of males) perceived their training volume to be high.

Motivation for floorball participation

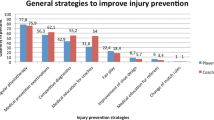

Motivation from the father to play floorball was significant for both male and female youth; however, the team was the greatest motivation for floorball participation in all players (Fig. 2). Siblings, coach, club environment and proximity to the facility were also significant motivators for floorball participation in females. For male floorball players, friends and sporting success were significant motivators.

Injury prevention expectations and injury risk perceptions

Protective glasses were worn by 85% of the players during training and match play, with 88% of male and 78% of female players always using protective eyewear. However, 9% never used protective glasses, with more female players (15%) not using protective eyewear than males (7%). Protective glasses must be worn by players up until 15 years of age at matches; however, only 87% (n = 352) of players aged under 15 years always wore protective glasses in training and matches and 4% (n = 16) of players this age never wore protective eyewear. Of players over 15 years, 45% (n = 26) never wore protective glasses, and another 45% (n = 26) always wore protective glasses both at training and at matches.

The Knee Control injury prevention exercise program had been used regularly by 14% (17% females and 12% males) of players and it was used sometimes by 28% (39% females, 27% males) players when they participated in other sports during the past year. Of all the players, 47% (37% females, 51% males) had never used the Knee Control program.

Of the potential injuries that can be sustained in floorball, fractures, eye injuries and concussions were perceived to be the most severe injuries, with lacerations and bruises perceived to be less severe (Fig. 3). There were no distinct sex differences in perception of the severity of injuries.

When the players were asked about their perception of likelihood of sustaining an injury during the season, 42% (43% females and 41% males) thought themselves unlikely to sustain an injury and 32% (31% females and 33% males) were neutral and believed an injury to be neither likely nor unlikely. In contrast, 26% of both females and males saw a likelihood that they could be injured playing floorball. Most players (93%) believed that sports injuries can be prevented, and only 3% did not believe that sports injuries can be prevented. There were no sex differences in the perceptions of injury risk or the possibility of preventing sports injuries.

Health problems at the start of the season

At the start of the season, most of the players reported good sleep and well-being (Fig. 4). On a scale of 0 (not stressed) to 10 (very stressed), the youth floorball players reported a mean stress of 2.8 ± 2.5 at the start of the season. On a scale of 0 (very good) to 10 (very bad), players reported mean sleep of 3.1 ± 2.3, and well-being of 2.5 ± 2.4. Youth female floorball players felt more stress with a median of 4 (IQR 2–6) compared to males with a median of 2 (IQR 0–4, P = 0.000). Contrary, females reported better well-being than males with median of 3 (IQR 1–5) versus 2 (IQR 0–3, P = 0.000). There was no difference in sleep between females, median 3 (IQR 1–5) and males, median 3 (IQR 0–3, n.s.).

Question 1 of the OSTRC questionnaire on health problems indicated that 33% (n = 148, 38% females and 30% males) of youth players were unable to fully participate in the sport without any health problems at the start of the floorball season. The reported health problems were 64% (n = 95) injuries and 36% (n = 53) illnesses. Of all injuries, 17% (13% females and 19% males) caused time-loss from sports and 17% (33% females and 9% males) required medical attention. Injuries were mainly to the lower limb (total 70%, 64% females, 72% males) and primarily located to the knee (total 48%, 50% females, 47% males).

Of all players, 85% (84% females, 87% males) played floorball (training or match) the week of the baseline survey. As illustrated in Table 3, 81% (77% females, 83% males) of players reported no reduction in their training volume at the start of the season. Pain was reported by 28% (32% females, 26% males) of players, and 13% of female and 8% of male players could not participate in floorball due to pain. Of the 95 reported injuries at the start of the season 28% (20% females and 31% males) were acute injuries and 72% (80% females and 69% males) were overuse injuries.

When the OSTRC severity score (range 0–100) was calculated, the mean severity score was 15 ± 30, with 13.6% (n = 61) of players reporting severe health problems (score ≥ 40) at the beginning of the season. There were more severe health problems in female floorball players (17%) than males (12%), whilst this did not reach statistical significance (U = 18,631.5, n.s.). Youth with health problems demonstrated significantly more stress, poorer sleep quality and poorer well-being than youth that reported no health problem at the start of the season (Table 4).

Discussion

The most important finding of the present study was that one in three players reported a health problem at the start of the season providing insight into the status of the athletes’ health leading into the season. The high prevalence of health problems is a concern; if injuries are left untreated, there is a potential for more severe and long-term adverse health consequences [3, 5, 15, 27, 28]. A novel finding of this study is that key motivators for floorball participation in youths were identified, providing important information to the sporting organisations aiming to retain sports participants.

Motivation for floorball participation

Understanding the factors that motivate for sports participation is particularly important when many countries, including Sweden, are attempting to increase activity levels in adolescents through sustainable youth sports programs. As the umbrella organisation for approximately 70 federations, the Swedish Sports Confederation’s strategy for Swedish sport 2025 has a strong focus on getting as many people as possible to play sports for as long as possible [20]. Our study found that a young player’s father, friends, coach and team significantly motivated them to participate in floorball. This might suggest that most youths are active in floorball because of the social aspects, i.e. that it is fun and allows them to be with their friends and be part of a team, and this should be a focus in youth sports to retain sports participants.

Overview of health problems and injury prevention expectations

The finding of this study revealed that 33% of non-elite youth floorball players reported a health problem at the beginning of the season extends previous research in Swedish elite youth athletes showing that one in three suffer an injury every week [25]. Similarly one in four Australian youth athletes participating in multiple contact sports reported an injury [10]. This is concerning, and it is likely that many athletes in our study carried an injury/health problem from the summer season that affected them at the start of the floorball season. The summer and winter sports seasons overlap with no clear pre-season and, therefore, players who play multiple sports may transition from one to other with little or no rest in-between. Although there are some similarities between pivoting sports such as floorball and football, it can be argued that the different surfaces (indoor vs. outdoor) and type of play can change the type of load [21]. Further, without a pre-season, athletes do not have adequate time to prepare for the sport with specific drills, thereby possibly increasing the risk of injury. Increasing adequate pre-season preparation can potentially reduce the risk of injury [13, 14, 26].

Research into the incidence and prevalence of overuse injuries in youth sports is scarce [8] and use of time-loss injury definitions underestimate the actual magnitude of overuse injuries [6]. We found that 28% of youth floorball players reported pain or were unable to play due to pain, with approximately three out of four injuries being overuse-related. A six-month prospective cohort study of Norwegian elite youth athletes playing a variety of endurance, team, and technical sports reported similar findings, with 37% players reporting overuse injuries [17]. The large number of overuse injuries is of concern in these young athletes. Youth specialising in one sport at an early age and training year-round have increased risk of overuse injuries [8]. This may be due to the structural damage and weakness because of inadequate recovery time and excessive stress impacting tissue remodelling. 17% of the youth included in this study attended a school with a sports profile, and this might be another plausible explanation to the high prevalence of health problems reported in this study. Playing a variety of different sports throughout the year as a form of cross-training may benefit physical development as well as develop transferable skills.

A majority of the youth floorball players felt that their training volume was high or very high. In youth athletes playing multiple contact team sports, the relationship between risk of injury and training volume is linear [10]. In addition, poor sleep, poor well-being and high stress have been associated with health problems [8, 24] and are modifiable injury risk factors. Therefore, it is essential to consider the impact of training load and recovery, particularly in youth athletes who have a developing musculoskeletal system. The preliminary cross-sectional findings of this study from the start of the season should be verified further using prospectively recorded data from the full season.

In this study cohort, most of the same athletes play football in the spring to autumn and then floorball in the winter to spring, and many of their parental coaches also transition between sports. Therefore, it is economical and practical to implement an injury prevention exercise program such as Knee Control for both sports, so the athletes can maintain their prevention program when they transition between sports. The larger SWIPE study excluded the floorball teams that already used the Knee Control injury prevention program, but 42% of the players still had used it in the last year as part of the other sport they play. This consistency in their preventive training is likely to be beneficial. Approximately 93% of the youth floorball players in this study considered that injuries could be prevented, indicating that there is reasonable ground to implement injury prevention programs.

Injury risk perceptions

Although there were no concussions reported at the beginning of the floorball season, most of the players perceived concussion to be a severe injury, indicating good awareness. This may be because of increased discussions, education campaigns and awareness programs of the importance of concussion management in sports. Also, the majority perceived eye injuries as serious, likely due to the increased attention on eye injuries in floorball. In Sweden, it is mandatory to wear protective eyewear until age 15 at floorball matches. Interestingly, 9% of the youth in our study never used protective eyewear, and 2% used them sometimes. Also, only 87% of players under 15 years always used protective eyewear, indicating that players are not fully adhering to mandatory safety requirements during matches and safety recommendations for training. It is possible that these players were playing matches with older peers where the protective eyewear rule was not as strictly enforced. It is also worrisome that 45% of players above 15 years never wore protective eyewear, since floorball is a high-risk sport for eye injuries, potentially leading to severe and enduring problems [2]. Four of ten players thought they were unlikely to sustain an injury during the floorball season and another 32% were neutral about a potential injury. More education and discussions surrounding injuries and prevention strategies, and to develop and make available easily accessible resources for the floorball players as part of sports safety initiative to promote safe and healthy sports is needed.

The use of single item global health questions to gain information about stress, sleep and well-being of the youth athletes can be a limitation of this study. Single item global health questions are established to provide reliable and valid information and are widely used in population health surveys, but they might not provide comprehensive and detailed information that can be gleaned from a multi-item measurement scale [1]. However, youths may find it difficult to perceive nuances in similarly alike questions in a multi-item survey and thus may answer all the questions in the same manner. Therefore, single item global health questions are deemed adequate to gain a “snap shot” of baseline general health status (stress, sleep and well-being) of youth athletes and the simplicity of these questions minimise the burden on study participants as they are taking part in a lengthy RCT. Another limitation is that the survey instrument was not validated for test–retest in youth floorball players. However, most of the questions used in this baseline survey were adopted from previous studies [6, 7, 16] and some of the content was modified to ensure that the survey is relevant and specific for youth floorball players in order to collect accurate self-reported data. Finally, due to the self-reported nature of data collection and reliance on young athletes’ memory, recall bias can be another limitation of this study. Prompting questions and limiting recall period to 1 week was used to overcome this limitation.

Conclusions

Social aspects were the greatest motivators for floorball participation, and organisations that aim to grow sports should focus more on this to retain participants. The high prevalence of health problems in youth at the beginning of a season is a concern; as such more effort, resources and priority should be given to sports safety programs. Many players believed that sports injuries can be prevented, possibly providing a fertile ground for implementation of such programs.

Abbreviations

- SWIPE:

-

Sport Without Injury ProgrammE

- OSTRC:

-

Oslo Sports Trauma Research Center

References

Bowling A (2005) Just one question: if one question works, Why ask several? J Epidemiol Community Health 59:342–345

Bro T, Ghosh F (2017) Floorball-related eye injuries: the impact of protective eyewear. Scand J Med Sci Sports 27:430–434

Cameron K, Mauntel T, Owens B (2017) The epidemiology of glenohumeral joint instability: incidence, burden, and long-term consequences. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev 25:144–149

Cao B, Bray F, Ilbawi A, Soerjomataram I (2018) Effect on longevity of one-third reduction in premature mortality from non-communicable diseases by 2030: a global analysis of the sustainable development goal health target. Lancet Glob Health 6:e1288–e1296

Carbone A, Rodeo S (2017) Review of current understanding of post-traumatic osteoarthritis resulting from sports injuries. J Orthop Res 35:397–405

Clarsen B, Myklebust G, Bahr R (2012) Development and validation of a new method for the registration of overuse injuries in sports injury epidemiology. Br J Sports Med 47:495–502

Clarsen B, Rønsen O, Myklebust G, Flørenes T, Bahr R (2014) The Oslo sports trauma research center questionnaire on health problems: a new approach to prospective monitoring of illness and injury in elite athletes. Br J Sports Med 48:754–760

DiFiori J, Benjamin H, Brenner J, Gregory A, Jayanthi N, Landry G et al (2014) Overuse injuries and burnout in youth sports: a position statement from the American medical society for sports medicine. Br J Sports Med 48:287–288

Ding D, Lawson KD, Kolbe-Alexander TL, Finkelstein EA, Katzmarzyk PT, Van Mechelen W et al (2016) The economic burden of physical inactivity: a global analysis of major non-communicable diseases. Lancet 388:1311–1324

Hartwig T, Gabbett T, Naughton G, Duncan C, Harries S, Perry N (2019) Training and match volume and injury in adolescents playing multiple contact team sports: a prospective cohort study. Scand J Med Sci Sports 29:469–475

International Floorball Federation (2018) Member Associations 2018. http://www.floorball.org/pages/EN/Member-Associations. Accessed 18 April 2018

Kondric M, Sindik J, Furjan-Mandic G, Schiefler B (2013) Participation motivation and student’s physical activity among sport students in three countries. J Sports Sci Med 12:10–18

Lehnert M, Stastny P, Tufano J, Stolfa P (2017) Changes in isokinetic muscle strength in adolescent soccer players after 10 weeks of pre-season training. Open Sports Sci J 10:27–36

Lehnert M, Xaverová Z, De Ste Croix M (2014) Changes in muscle strength in u19 soccer players during an annual training cycle. J Hum Kinet 42:175–185

Manley G, Gardner A, Schneider K, Guskiewicz K, Bailes J, Cantu R et al (2017) A systematic review of potential long-term effects of sport-related concussion. Br J Sports Med 51:969–977

McKay C, Merrett C, Emery C (2016) Predictors of FIFA 11 + implementation intention in female adolescent soccer: an application of the health action process approach (HAPA) model. Int J Environ Res Public Health 13:657

Moseid C, Myklebust G, Fagerland M, Clarsen B, Bahr R (2018) The prevalence and severity of health problems in youth elite sports: a 6-month prospective cohort study of 320 athletes. Scand J Med Sci Sports 28:1412–1423

Pasanen K, Bruun M, Vasankari T, Nurminen M, Frey W (2017) Injuries during the international floorball tournaments from 2012 to 2015. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med 1:e000217

Pasanen K, Parkkari J, Pasanen M, Hiilloskorpi H, Mäkinen T, Järvinen M et al (2008) Neuromuscular training and the risk of leg injuries in female floorball players: cluster randomised controlled study. BMJ 337:a295

Riksidrottsförbundet (2018) Verksamhetsinriktning 2018–2019. http://www.rf.se/globalassets/riksidrottsforbundet/dokument/dokumentbank/rfs-verksamhet/verksamhetsinriktning-2018-19.pdf?w=900&h=900. Accessed 15 April 2018

Thomson A, Whiteley R, Bleakley C (2015) Higher shoe-surface interaction is associated with doubling of lower extremity injury risk in football codes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med 49:1245–1252

Tranaeus U, Götesson E, Werner S (2016) Injury profile in Swedish elite floorball: a prospective cohort study of 12 teams. Sports Health 8:224–229

Ullrich-French S, Smith AL (2009) Social and motivational predictors of continued youth sport participation. Psychol Sport Exerc 10:87–95

von Rosen P, Frohm A, Kottorp A, Fridén C, Heijne A (2017) Too little sleep and an unhealthy diet could increase the risk of sustaining a new injury in adolescent elite athletes. Scand J Med Sci Sports 27:1364–1371

Von Rosen P, Heijne A, Frohm A, Fridén C, Kottorp A (2018) High injury burden in elite adolescent athletes: a 52-week prospective study. J Athl Train 53:262–270

Watson A, Brickson S, Brooks MA, Dunn W (2017) Preseason aerobic fitness predicts in-season injury and illness in female youth athletes. Orthop J Sports Med. 5:2325967117726976

Whittaker J, Woodhouse L, Nettel-Aguirre A, Emery C (2015) Outcomes associated with early post-traumatic osteoarthritis and other negative health consequences 3–10 years following knee joint injury in youth sport. Osteoarthr Cartil 23:1122–1129

Whittaker JL, Toomey CM, Nettel-Aguirre A, Jaremko JL, Doyle-Baker PK, Woodhouse LJ et al (2019) Health-related outcomes following a youth sport-related knee injury. Med Sci Sports Exerc 51:255–263

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the participating players and coaches, the help from Tania Nilsson RPT, MSc, Gustav Ljunggren RPT, MSc, Oskar Kjellander MS and Hanna Lindblom RPT, PhD student with the data collection, Markus Waldén MD, PhD, Taru Tervo PhD and Prof Tor Söderström for valuable input on the baseline questionnaire, and Emil Risberg The Swedish Floorball Federation for administrative assistance. The Sport Without Injury ProgrammE is funded by the Swedish Research Council (2015-02414) and the Swedish Research Council for Sport Science (P2018-0167).

Funding

The Sport Without Injury ProgrammE is funded by the Swedish Research Council (2015-02414) and the Swedish Research Council for Sport Science (P2018-0167). Nirmala Kanthi Panagodage Perera was supported by Australia Awards—Endeavour Fellowship from the Department of Education and Training, Australia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

NP Constructed the SWIPE baseline database, analysed and interpreted the data, and wrote the first manuscript draft. MH Involved in conception, design and execution of the SWIPE project, interpretation of the data and critically revising the manuscript. IÅ Involved in execution of the SWIPE project, data collection, interpretation of the data and critically revising the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Linköping (Project number Dnr 2017/294-31).

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Perera, N.K.P., Åkerlund, I. & Hägglund, M. Motivation for sports participation, injury prevention expectations, injury risk perceptions and health problems in youth floorball players. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 27, 3722–3732 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-019-05501-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-019-05501-7