Abstract

Purpose

To investigate how range of motion of the hips and the lumbar spine are affected by continued elite, alpine skiing in young subjects, with and without a magnetic resonance imaging verified cam morphology, in a 2-year follow-up study. The hypothesis is that skiers with cam morphology will show a decrease in hip joint range of motion as compared with skiers without cam, after a 2-year follow-up.

Method

Thirty adolescent elite alpine skiers were examined at the baseline (mean age 17.3 ± 0.7 years) and after 2 years. All skiers were examined for the presence of cam morphology (α-angle > 55°) using magnetic resonance imaging at the baseline. Clinical examinations of range of motion in standing lumbar flexion and extension, supine hip flexion, internal rotation, FABER test and sitting internal rotation and external rotation were performed both at the baseline and after 2 years.

Results

Skiers with and without cam morphology showed a significant decrease from baseline to follow-up in both hips for supine internal rotation (right: mean − 13.3° and − 10.9° [P < 0.001]; left: mean − 7.6° [P = 0.004] and − 7.9° [P = 0.02]), sitting internal rotation (right: mean − 9.6° and − 6.3° [P < 0.001]; left: mean − 7.6° [P = 0.02] and − 3.3° [P = 0.008]) and sitting external rotation (right: mean − 16.9° and − 11.4° and left: mean − 17.9° and − 14.5° [P < 0.001]) and were shown to have an increased left hip flexion (mean + 8.4° and + 4.6° [P = 0.004]). Skiers with cam were also shown to have an increased right hip flexion (mean + 6.4° [P = 0.037]). Differences were found between cam and no-cam skiers from baseline to follow-up in the sitting internal rotation in both hips (right: mean 3.25°, left: mean 4.27° [P < 0.001]), the right hip flexion (mean 6.02° [P = 0.045]) and lumbar flexion (mean − 1.21°, [P = 0.009]).

Conclusion

Young, elite alpine skiers with cam morphology decreased their internal rotation in sitting position as compared with skiers without the cam morphology after 2 years of continued elite skiing.

Level of evidence

II.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Hip and groin pains are common problems in the population, and especially in athletes. Femoroacetabular impingement syndrome (FAIS) has lately been given more attention as a major cause of hip pain [1, 2], and is defined as a clinical disorder in the hip joint where a combination of symptoms, clinical signs and imaging findings (abnormal morphology viewed on plain radiography, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computed tomography) are manifested [3]. FAIS is either present as an abnormal morphology at the femoral head-neck junction (cam) or as an abnormality in the acetabular shape or orientation causing over-coverage of the femoral head (pincer) [4, 5]. These two can also be present together, as a mixed type. A result of this anatomic abnormal morphology, an impingement occurs when the femoral head-neck junction collides with acetabulum particularly during hip flexion and internal rotation (IR) [6]. In addition to pain, the scientific literature has shown growing evidence that a cam morphology might lead to decreased range of motion (ROM), damage to the cartilage, labrum tears and predispose to the development of hip joint osteoarthritis (OA) [4, 6,7,8,9]. Agricola et al. [7] reported that individuals with both an α-angle > 83° and limited hip joint IR (< 20°) were at high risk of end-stage OA within 5 years (adjusted odds ratio 25.21).

Previous studies have reported that patients with FAIS often have a motion and/or position related pain in the groin and/or hip joint, reduced hip flexion and IR and positive anterior impingement test /FADDIR test [3, 9, 10]. Agnvall et al. [11] found a significantly reduced hip flexion, supine IR and IR in three different sitting positions and a higher frequency of pain/discomfort in the FADDIR test, when comparing young adolescents with MRI-verified cam morphology and with no-cam [11].

The etiology of FAIS is not entirely known. However, it has been postulated that participating in high-impact sports during the growth period may predispose to cam morphological changes [12, 13]. It is suggested that vigorous sporting activity and repetitive micro-trauma to the proximal femoral physis [6] may lead to a reactive bone formation and the development of cam during growth spurt [14, 15].

Several studies have reported radiological changes of the cam morphology as high as 56–89% in young athletes participating in vigorous sporting activity, such as soccer [16, 17], basketball [18] and ice-hockey [19,20,21]. In healthy and less active asymptomatic populations, the prevalence of the cam morphology has been reported to be present in 10–50% on imaging [22, 23].

Alpine skiing is a forceful sport with great impact to the hip joints [24]. A recent study showed that young elite skiers are at a higher risk for having cam (49%) in comparison to young controls (19%) [25]. To our knowledge, it is unclear how the cam morphology affects the ROM in the lumbar spine and the hips over time with continuous vigorous sporting activity, e.g. alpine skiing.

The aim of the present study is to investigate how the ROM in the hip joints and the lumbar spine is affected by continued elite, alpine skiing in young subjects with and without an MRI-verified cam morphology after 2-year follow-up. The hypothesis is that young, elite alpine skiers with cam morphology will show a decrease in hip joint ROM as compared with young, elite alpine skiers without cam, after 2-year follow-up.

Materials and methods

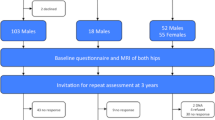

All students (n = 36, grade 1–2, 16–18 years) attending the Åre Ski Academy were invited to participate in this prospective, cohort study at baseline in 2014 and during follow-up in 2016. One subject was excluded at baseline due to FAIS-surgery. Thirty subjects (13 females and 17 males) were available for final analysis. Reasons for the reduced number of subjects were that only data from skiers who participated both at baseline and the follow-up were used and difficulties to get the skiers to be present at the investigations or failure to attend appointments despite several attempts. Participation was totally voluntary and informed written consent was given by all individuals. For participants younger than 18 years, informed written consent was also obtained from one parent.

The inclusion criteria were students at the Åre Ski Academy, training and competing at elite level. Participants were excluded if they were pregnant or had a history of previous surgery to the back, pelvis and/or hip.

The present study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Gothenburg at the Sahlgrenska Academy, Gothenburg University, Gothenburg, Sweden, (ID number: 692-13).

MRI examination

At baseline, 2014, all participants underwent MRI examinations of both hips at the Radiological Department at Östersund Hospital, Sweden. No intra-articular contrast was used. The MRI was performed on a GE Optima 450 Wide 1.5T (Milwaukee, USA) using a coil surface HD 8ch Cardiac array by GE. Most cam morphological changes are in the anterosuperior head-neck junction [5, 6]. Therefore, the α-angle was measured at seven clockwise positions in 30° intervals, from 9 o’clock (posterior) to 3 o’clock (180°, anterior) to determine morphological findings at the femoral head-neck junction.

The α-angle was measured, according to Nötzli et al. between the femoral neck axis and a line from the center of the femoral head to a point where the contour of the femoral head-neck junction exceeds the radius of the femoral head [2]. The α-angle defines the presence of the cam morphology and previous studies have used a threshold of 55–60° [20, 21, 26]. In the present study, an α-angle of 55° or above is considered as a cam morphology.

The MRI scans were evaluated and measured unidentified by one experienced radiologist together with a resident radiologist according to a standardized protocol. The interobserver reliability (intraclass correlation, ICC) of the α-angle measurement was previously reported to be 0.75 [11].

Clinical examination

The clinical examinations were carried out at Åre Ski Academy, Östersund, Sweden, following a standardized protocol, according to Agnvall et al. [11], both at baseline and at the follow-up. All clinical examinations were performed by two examiners (co-authors CA and ASA) in a specific order. Intra- and interobserver tests for all physical examination measurements have previously been reported to be good to excellent, ICC 0.77–0.78 and 0.83–0.94, respectively [11].

All participants were first examined in a standing position with both feet together and arms hanging by their sides. A non-invasive measurement of lumbar flexion and extension was performed with a modified Debrunner Kyphometer (Protek AG, Bern, Schweiz) [27]. Secondly, the participants were examined in the supine position. Hip flexion (Fig. 1), hip internal rotation (IR) in 90° hip- and kneeflexion (Fig. 2) and FABER (flexion, abduction, external rotation) test (Fig. 3) were measured using a Digital Goniometer (DG) (HALO medical devices, Australia) [28] together with a Universal Goniometer (UG) with extended arms, 40 cm [29]. If the angles between the two devices differed, the angle measured by the UG was used for the final analysis. Final examinations were in a sitting, neutral position measuring passive hip IR and external rotation (ER) (Fig. 4) using a DG together with a UG as described previously. All measurements were recorded in degrees (°). We refer to the original work for a full description of the technical aspects [11].

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 25.0 (Armonk, NY: IBM Corp). The description of continuous data was expressed in terms of the means and standard deviation (SD). The normal distribution of the data was tested with a Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. A paired t test was used to compare continuous data between baseline and the follow-up and an independent t test was used to evaluate the differences between the cam and no-cam group. The hips are analyzed separately, i.e. hips with an α-angle > 55° in the right hip (but not in the left hip) were included in the cam group when analyzing the results for the right hip, and similarly for the left hip. When analyzing the lumbar spine measurements, an α-angle > 55° in any hip were included in the cam group. Categorical data were expressed as frequencies and percentage and a Chi-square test was used for these data. All tests were two-sided, and the significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results

A total of 56 hips in 30 (13 females and 17 males) adolescent elite skiers were available for the final analysis, of which 19 hips (34%, 9 right and 10 left) in 14 subjects (47%) had a cam morphology (α-angle > 55°) at baseline. Hips lost for final analysis were due to bad imaging quality and therefore inability to interpret the MRI scans. Baseline characteristics for the study population are summarized in Table 1. All follow-ups were at 24 months. The cam group consisted of four females (right: 3; left: 2) and 10 males (right: 6; left: 8), whilst the no-cam group consisted of nine females and seven males. The two groups were similar in terms of age, gender and BMI. All skiers continued to ski at elite level during follow-up time. The skiers lost to follow-up were similar regard to age, gender, height, weight, BMI, prevalence of hip deformities or symptoms.

Tables 2, 3 and 4 summarize lumbar spine, right hip and left hip ROM differences between baseline and follow-up in both the cam and no-cam group. Both the cam and no-cam group had significant decrease in hip ROM for supine IR in both hips, sitting IR, sitting ER and an increase in the left hip flexion. The cam group had a significant increase for the right hip flexion which appeared different from the no-cam group. In contrast, the no-cam group was shown to have a decrease in the right FABER test, which was not found in the cam group.

There was a significant difference from baseline to follow-up between the cam and the no-cam group (Tables 2, 3, 4). The cam group had a greater decrease in lumbar flexion (mean − 1.21°, [P = 0.009]) and sitting IR in both hips (right: mean − 3.24°; left: mean − 4.27° [P < 0.001]) and a greater range in the right hip flexion (mean + 6.02° [P = 0.045]). No other significant differences were shown between the groups.

Discussion

The most important findings in the present study were that adolescent skiers decreased their hip IR and ER regardless if they had MRI-verified cam morphological changes or not after 2 years follow-up. Young skiers with cam also increased their hip flexion and, additionally, were shown to have a statistical greater decrease in sitting IR and larger increase in the right hip flexion, from baseline to follow-up, as compared with the no-cam skiers. This was, in part, similar to the study by Agnvall et al. [11] where skiers with cam had significantly lesser IR in both supine and sitting positions as compared with the no-cam skiers. These minor differences between cam and no-cam, in the present study, might be explained by the late fusion of the pelvic bones. Partial fusion of the iliac crest occurs from the age of 15–22 years, with complete union in all individuals by the age of 23 years [30]. One may speculate that the acetabulum permits slight movement before fusion and therefore the cam morphological change does not affect the hip ROM. As the fusion progresses (i.e. the participants gets older) the acetabulum might not be as compromising and the hip ROM may therefore be affected.

The hypothesis in this present study was that skiers with MRI-verified cam morphology will show a decrease in hip joint ROM as compared with no-cam skiers after 2 years follow-up. This was true for hip IR in sitting position, but rejected for all other measurements that were shown to be similar between the groups or, as for the hip flexion, did increase instead of decrease. These results might be caused by early sporting participation with an adaption to the athletic activity (i.e. extra-articular hip conditions, e.g. soft tissue pathologies, and/or muscular stiffness) rather than as a response to a cam morphology.

Current literature highlights a lack of follow-up studies investigating hip ROM in populations with the cam morphology. Hip IR is the most common ROM measurement in studies of FAIS, as this suggests to be an important clinical finding in the presentation of FAIS [3]. Despite that supine IR did decrease from baseline (28–33°) to the follow-up (14–25°) in both groups, these results are consistent with earlier studies, in athletes (11–30°) [18, 31,32,33] and in individuals with radiological cam morphology (16–28°) [17, 34, 35].

The present study reported that the alpine skiers were shown to have reduced hip IR and ER from baseline, with a mean age of 17 years, to the follow-up, with a mean age of 19 years. This corresponds to the natural change of hip ROM that can be seen in both the normal population [36] and athletes [18, 33]. Siebenrock et al. [18] showed a decrease in hip IR when stratified into age groups (regardless cam or not), where 13–15-year-old basketball players had a mean IR of 23.4° as compared with 16–21-year-old players who had only 13.6°. They suggested a physiological loss of IR attributable to decreasing femoral neck anteversion during growth. Moreover, Manning and Hudson [33] compared junior soccer players (mean age 17.6 years) to senior soccer players (mean age 26.3 years) and found senior soccer players to be less flexible in hip flexion, IR and ER. In the study by Sankar et al. [36], who examined hip ROM in a normal population of 2–17-year-olds, found a trend toward lesser hip ROM with higher age in almost every participant. This was more pronounced in the male population. An interesting aspect is that these studies showed less flexibility also in flexion, as compared with the skiers in the present study that showed an increase in hip flexion. Though, the present result matches the review by Andersen and Montgomery [24], who reported alpine skiers had significantly better flexibility as compared to non-athletes in a hip flexion/extension testing. If the increased flexion is a response to the lesser hip IR and ER or to the highly dynamic ski performance and training that is performed in primarily a squatting position, is still unclear and needs further investigation.

Hip ER, in the present study, was shown to be in line with earlier studies in athletes [17, 32, 37] when compared at baseline, whilst the results from the follow-up are approximately 10° lower for both the cam and no-cam group. This may be due to an actual reduction in the hip joint ROM or muscular stiffness in the hip rotators, as a response to the alpine skiing [17].

The FABER test is commonly used as a diagnostic test in patients with hip and/or groin pain and is considered positive if the pain is reproduced and/or there is a decrease in ROM as compared with the non-affected leg [38]. The most common method to measure hip ROM with the FABER test is with a stick between the lateral femoral condyle on the test side and the examination table. However, this method has not been able to distinguish between cam and no-cam morphology [20]. In the present study, the hip ROM in FABER test was measured with a digital goniometer and the results were shown to conflict. The no-cam group had significantly lesser angle in the right hip from baseline to the follow-up, this was not shown for the cam group. In the left hip, none of the groups reached significant levels. Moreover, when comparing the groups from baseline to follow-up, there was no difference in either hip. Some previous studies, using this angle-measuring method, could not either report an association between hip ROM in the FABER test and participants with cam morphology [11, 32]. As the intra- and interobserver reliability was shown to be good to excellent in the present study [11], the likelihood of measurement errors due to the examiners is reduced. One may, therefore, speculate if the FABER test should be a predictor for hip ROM in patients with hip/groin pain, regardless of using the stick or the goniometer.

None of the groups did show any change from baseline to follow-up for the lumbar spine measurements. However, when comparing the groups from baseline to follow-up, a statistical difference was shown for LF. This may be due to a type-II error because of the relatively limited cohort, and the difference of 1.21° in the LF between the cam group and the no-cam group, for which the P value approaches significance, and similarly so for the sitting IR and right hip flexion. Furthermore, one must also take into consideration that these hip ROM differences between cam and no-cam were minor (3–6°) and did not reach the minimally detectable change (MDC) of 7° that Tak et al. [17] did calculate.

It appears that there is a discrepancy between studies investigating hip ROM and its association to cam [17, 19, 32, 34, 39]. This might rather be related to different measuring methods than actual ROM differences, and therefore, makes it difficult to compare results and draw final conclusions. The present study showed a significant difference after 2 years between the cam group and the no-cam group in sitting IR but not in supine IR. This may suggest that measuring hip IR in sitting position could be more sensitive to distinguish between cam and no-cam. Studies of hip IR in sitting position are sparse. Agnvall et al. [11] showed a significant difference for hip IR between cam and no-cam in young subjects in three different sitting positions. In contrast, Brunner et al. [39] failed to find any difference when comparing ice-hockey players with symptomatic FAIS, asymptomatic FAIS and no FAIS. The method in their study differs from the present study as they used an examination chair with a standard load of 5 kg applied on a lever arm, which passively moved both legs into hip IR. In this position, maximum IR was held for 30 s and then was measured bilaterally with an inclinometer. Moreover, they also included both types of FAIS: cam and pincer. The sitting position makes it possible to control and minimize counter-movements in the lumbar spine and pelvis, therefore, giving the results the possibility of greater reliability. Many patients with cam report difficulties and pain associated with prolonged sitting. Therefore, this position in combination with hip IR may have another impact on the hip as compared to that in the supine position. To better understand how hip ROM is affected by an abnormal morphology (e.g. cam), the activity that is related to their symptoms requires further research.

Several limitations of this study need to be acknowledged. Firstly, the skiers were only examined for cam morphology defined as an α-angle > 55° at the baseline. If, and how, hip morphology may or may not have been changed throughout the 2 years remains unclear. Secondly, the skiers were not examined for hip morphological findings (e.g. pincer, acetabular orientation) other than α-angle, which might affect the hip ROM. Audenaert et al. [40] proposed in their study the importance of examining the general hip morphological characteristics, especially femoral anteversion and acetabular coverage, and referred to the possibilities of an earlier collision between the femur and acetabulum in individuals with greater femoral retroversion. Thirdly, the present study only examined the hip ROM relative to cam, regardless of the presence of pain in the hip/groin or the lumbar spine. If the skiers had pain at baseline but not at the follow-up, or vice versa, the results might be affected false negative/positive. Furthermore, some studies have reported that patients with previous or present symptom/pain in the hip/groin are shown to have a lesser hip ROM as compared to asymptomatic persons [17, 34, 41]. It has previously been shown by Sadeghisiani et al. [42] in their systematic review that asymmetrical and limited hip IR and total hip rotation appear to be more common findings in patients who also present with low back pain.

The accuracy and interpretation of both radiological and clinical measurements is always dependent on the examiner, which is a limitation in itself. The present study attempted to limit such a variation by using only two radiologists and two collaborating examiners for the clinical examinations, alongside testing for intra- and inter-reliability.

The size of the sample group is a limitation, and a larger one might have revealed a greater difference between the cam and no-cam groups. However, the homogeneity of the present study may also be viewed as a strength, with respect to the sample of adolescent elite skiers is homogenous with respect to loading and levels of activity.

The clinical relevance of the present study highlights that elite alpine skiing during adolescence may cause hip ROM changes. These changes might be an adaption of soft tissues to the loads that alpine skiing requires, a physiological change during growth and/or an answer to the presence of a cam morphology in the hip joint.

Conclusion

Adolescent elite alpine skiers changed their hip ROM after 2 years of continued skiing and the presence of MRI-verified cam morphology did correlate with a greater decrease in internal rotation in sitting position.

Abbreviations

- FAIS:

-

Femoroacetabular impingement syndrome

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- ROM:

-

Range of motion

- IR:

-

Internal hip rotation

- ER:

-

External hip rotation

- LF:

-

Lumbar flexion

- LE:

-

Lumbar extension

- UG:

-

Universal goniometer

- DG:

-

Digital goniometer

References

Domb BG, Jackson TJ, Carter CC, Jester JR, Finch NA, Stake CE (2014) Magnetic resonance imaging findings in the symptomatic hips of younger retired national football league players. Am J Sports Med 42(7):1704–1709

Nötzli H, Wyss T, Stoecklin C, Schmid M, Treiber K, Hodler J (2002) The contour of the femoral head-neck junction as a predictor for the risk of anterior impingement. J Bone Jt Surg Br 84(4):556–560

Griffin D, Dickenson E, O’Donnell J, Awan T, Beck M, Clohisy J et al (2016) The Warwick agreement on femoroacetabular impingement syndrome (FAI syndrome): an international consensus statement. Br J Sports Med 50(19):1169–1176

Ganz R, Parvizi J, Beck M, Leunig M, Nötzli H, Siebenrock KA (2003) Femoroacetabular impingement: a cause for osteoarthritis of the hip. Clin Orthop Relat Res 417:112–120

Ito K, Minka-II M-A, Leunig M, Werlen S, Ganz R (2001) Femoroacetabular impingement and the cam-effect a MRI-based quantitative anatomical study of the femoral head-neck offset. J Bone Jt Surg Br 83(2):171–176

Siebenrock K, Wahab KA, Werlen S, Kalhor M, Leunig M, Ganz R (2004) Abnormal extension of the femoral head epiphysis as a cause of cam impingement. Clin Orthop Relat Res 418:54–60

Agricola R, Heijboer MP, Bierma-Zeinstra SM, Verhaar JA, Weinans H, Waarsing JH (2013) Cam impingement causes osteoarthritis of the hip: a nationwide prospective cohort study (CHECK). Ann Rheum Dis 72(6):918–923

Beck M, Kalhor M, Leunig M, Ganz R (2005) Hip morphology influences the pattern of damage to the acetabular cartilage femoroacetabular impingement as a cause of early osteoarthritis of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br 87(7):1012–1018

Clohisy JC, Knaus ER, Hunt DM, Lesher JM, Harris-Hayes M, Prather H (2009) Clinical presentation of patients with symptomatic anterior hip impingement. Clin Orthop Relat Res 467(3):638–644

Sink EL, Gralla J, Ryba A, Dayton M (2008) Clinical presentation of femoroacetabular impingement in adolescents. J Pediatr Orthop 28(8):806–811

Agnvall C, Swärd Aminoff A, Todd C, Jónasson P, Thoreson O, Swärd L et al (2016) Range of hip-joint motion is correlated to MRI-verified pathological cam deformity in adolescent elite skiers. Orthop J Sports Med. https://doi.org/10.1177/2325967117711890

Murray R, Duncan C (1971) Athletic activity in adolescence as an etiological factor in degenerative hip disease. J Bone Jt Surg Br 53(3):406–419

Siebenrock KA, Behning A, Mamisch TC, Schwab JM (2013) Growth plate alteration precedes cam-type deformity in elite basketball players. Clin Orthop Relat Res 471(4):1084–1091

Agricola R, Bessems JH, Ginai AZ, Heijboer MP, van der Heijden RA, Verhaar JA et al (2012) The development of Cam-type deformity in adolescent and young male soccer players. Am J Sports Med 40(5):1099–1106

Agricola R, Heijboer MP, Ginai AZ, Roels P, Zadpoor AA, Verhaar JA et al (2014) A cam deformity is gradually acquired during skeletal maturation in adolescent and young male soccer players: a prospective study with minimum 2-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med 42(4):798–806

Gerhardt MB, Romero AA, Silvers HJ, Harris DJ, Watanabe D, Mandelbaum BR (2012) The prevalence of radiographic hip abnormalities in elite soccer players. Am J Sports Med 40(3):584–588

Tak I, Glasgow P, Langhout R, Weir A, Kerkhoffs G, Agricola R (2016) Hip range of motion is lower in professional soccer players with hip and groin symptoms or previous injuries, independent of cam deformities. Am J Sports Med 44(3):682–688

Siebenrock K, Ferner F, Noble P, Santore R, Werlen S, Mamisch T (2011) The cam-type deformity of the proximal femur arises in childhood in response to vigorous sporting activity. Clin Orthop Relat Res 469(11):3229–3240

Lerebours F, Robertson W, Neri B, Schulz B, Youm T, Limpisvasti O (2016) Prevalence of Cam-type morphology in elite ice hockey players. Am J Sports Med 44(4):1024–1030

Philippon MJ, Ho CP, Briggs KK, Stull J, LaPrade RF (2013) Prevalence of increased alpha angles as a measure of cam-type femoroacetabular impingement in youth ice hockey players. Am J Sports Med 41(6):1357–1362

Siebenrock KA, Kaschka I, Frauchiger L, Werlen S, Schwab JM (2013) Prevalence of cam-type deformity and hip pain in elite ice hockey players before and after the end of growth. Am J Sports Med 41(10):2308–2313

Frank JM, Harris JD, Erickson BJ, Slikker W, Bush-Joseph CA, Salata MJ et al (2015) Prevalence of femoroacetabular impingement imaging findings in asymptomatic volunteers: a systematic review. Arthroscopy 31(6):1199–1204

Hack K, Di Primio G, Rakhra K, Beaulé PE (2010) Prevalence of cam-type femoroacetabular impingement morphology in asymptomatic volunteers. J Bone Jt Surg Am 92(14):2436–2444

Andersen RE, Montgomery DL (1988) Physiology of alpine skiing. Sports Med 6(4):210–221

Todd C, Witwit W, Kovac P, Swärd A, Agnvall C, Jonasson P et al (2016) Pelvic retroversion is associated with flat back and cam type femoro-acetabular impingement in young elite skiers. J Spine. https://doi.org/10.4172/2165-7939.1000326

Tak I, Weir A, Langhout R, Waarsing JH, Stubbe J, Kerkhoffs G (2015) The relationship between the frequency of football practice during skeletal growth and the presence of a cam deformity in adult elite football players. Br J Sports Med 49(9):630–634

Öhlén G, Spangfort E, Tingvall C (1989) Measurement of spinal sagittal configuration and mobility with Debrunner’s kyphometer. Spine 14(6):580–583

Carey MA, Laird DE, Murray KA, Stevenson JR (2010) Reliability, validity, and clinical usability of a digital goniometer. Work 36(1):55–66

Gajdosik RL, Bohannon RW (1987) Clinical measurement of range of motion review of goniometry emphasizing reliability and validity. Phys Ther 67(12):1867–1872

Berge C (1998) Heterochronic processes in human evolution: an ontogenetic analysis of the hominid pelvis. Am J Phys Anthropol 105(4):441–459

Czuppon S, Prather H, Hunt DM, Steger-May K, Bloom NJ, Clohisy JC et al (2017) Gender-dependent differences in hip range of motion and impingement testing in asymptomatic college freshman athletes. PM R 9(7):660–667

Jonasson P, Thoreson O, Sansone M, Svensson K, Sward A, Karlsson J et al (2016) The morphologic characteristics and range of motion in the hips of athletes and non-athletes. J Hip Preserv Surg 3(4):325–332

Manning C, Hudson Z (2009) Comparison of hip joint range of motion in professional youth and senior team footballers with age-matched controls: an indication of early degenerative change? Phys Ther Sport 10(1):25–29

Audenaert E, Van Houcke J, Maes B, Vanden Bossche L, Victor J, Pattyn C (2012) Range of motion in femoroacetabular impingement. Acta Orthop Belg 78(3):327–332

Ng KG, Lamontagne M, Beaulé PE (2016) Differences in anatomical parameters between the affected and unaffected hip in patients with bilateral cam-type deformities. Clin Biomech (Bristol Avon) 33:13–19

Sankar WN, Laird CT, Baldwin KD (2012) Hip range of motion in children: what is the norm? J Pediatr Orthop 32(4):399–405

Kapron AL, Anderson AE, Peters CL, Phillips LG, Stoddard GJ, Petron DJ et al (2012) Hip internal rotation is correlated to radiographic findings of cam femoroacetabular impingement in collegiate football players. Arthroscopy 28(11):1661–1670

Tijssen M, van Cingel R, Willemsen L, de Visser E (2012) Diagnostics of femoroacetabular impingement and labral pathology of the hip: a systematic review of the accuracy and validity of physical tests. Arthroscopy 28(6):860–871

Brunner R, Maffiuletti NA, Casartelli NC, Bizzini M, Sutter R, Pfirrmann CW et al (2016) Prevalence and functional consequences of femoroacetabular impingement in young male ice hockey players. Am J Sports Med 44(1):46–53

Audenaert EA, Peeters I, Vigneron L, Baelde N, Pattyn C (2012) Hip morphological characteristics and range of internal rotation in femoroacetabular impingement. Am J Sports Med 40(6):1329–1336

Khanna V, Caragianis A, DiPrimio G, Rakhra K, Beaulé PE (2014) Incidence of hip pain in a prospective cohort of asymptomatic volunteers is the cam deformity a risk factor for hip pain? Am J Sports Med 42(4):793–797

Sadeghisani M, Manshadi F, Kalantari K, Rahimi A, Namnik N, Karimi M et al (2015) Correlation between hip rotation range-of-motion impairment and low back pain. A literature review. Ortop Traumatol Rehabil 17(5):455–462

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Flemming Pedersen, MD, Zaid Obady, MD, at the Department of Radiology at Östersunds Hospital, Sweden, for their help with the radiological examination and interpretation. The authors would also like to thank Mr Christer Johansson, OrigoVerus AB, Gothenburg, Sweden, for statistical assistance. The authors acknowledge the financial support of the Medical Society of Gothenburg, Sweden, Governmental grants under the ALF agreement, Project grants under FoU-council, Gothenburg and South Bohuslän, The Healthcare Board, Region Västra Götaland (Hälso- och sjukvårdsstyrelse) and Carl Benett AB.

Funding

No funding was used.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JA contributed substantially to the study design, conception, acquisition of data analysis and interpretation of data and writing and drafting the manuscript for critical revision. ASA and CA participated in the study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation. ASA, CT, CA, OT, PJ, JK, and AB contributed significantly and participated with writing of the manuscript. All authors approved final manuscript prior to submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the regional and institutional research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. For participants younger than 18 years, informed written consent was also obtained from one parent.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Abrahamson, J., Aminoff, A.S., Todd, C. et al. Adolescent elite skiers with and without cam morphology did change their hip joint range of motion with 2 years follow-up. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 27, 3149–3157 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-018-5010-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-018-5010-7