Abstract

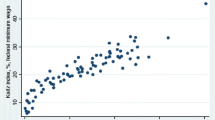

This study examines the heterogeneous impacts of minimum wages, which could affect low-income workers’ earnings and employment opportunities, on crime rates across neighboring communities. Using geo-tagged reported crime incident data from 18 major U.S. cities, we find that minimum wage increases reduce violent crime rates notably more in low-income communities than in high-income ones. On average, a one-dollar real minimum wage increase narrows the disparity in quarterly violent crime rates between low- and high-income communities by 12%. The impact varies considerably across different types of cities. The income effect resulting from raising the minimum wage is the main contributing factor.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Using 1990–2000 annual data on the largest 239 U.S. cities, Fernandez et al. (2014) find that minimum wage increases are associated with reductions in property and violent crimes. More recently, Agan and Makowsky (2021) examine the prison release records across 43 states in the United States from 2000–2014 and find that minimum wage increases are associated with a decline in recidivism, primarily by reducing property and drug crimes. By contrast, some studies document a positive relationship between minimum wages and crime. Beauchamp and Chan (2014) exploit changes in state and federal minimum wage laws from 1997 to 2010 and find a positive effect of minimum wage increases on crime for people employed at a binding wage. Fone et al. (2023) assess the impact of minimum wages on crime using data from multiple sources and find that minimum wage increases do not reduce crime and rather increase property crime arrests among those aged 16–24. Specifically, Braun (2019) uses a search-theoretic framework and shows a U-shaped relationship between the aggregate crime rate and the minimum wage.

While Dube et al. (2010), Harasztosi and Lindner (2019) and Cengiz et al. (2019) show the disemployment effect is small, Sabia et al. (2012), Meer and West (2016), Jardim et al. (2018), and Clemens and Wither (2019) reveal a large disemployment effect. By contrast, Card (1992) and Giuliano (2013) document a positive employment effect. With regard to household income, Neumark and Wascher (2002) and Burkhauser et al. (2023) suggest that rising minimum wage might reduce household income of lower-skilled workers via its disemployment effect. However, Aaronson et al. (2012) and Dube (2019) demonstrate that an increase in minimum wage raises household income.

For example, Card (1992) and Neumark and Wascher (2003) find that raising the minimum wage reduces school enrollment, whereas Campolieti et al. (2005) show that such an increase has no significant effect on teenagers’ school enrollment rate. Pacheco and Cruickshank (2007) document that increasing the minimum wage has a statistically significant negative effect on teenagers’ school enrollment rate, but they find no significant impact on the enrollment rate of 20–24-year-olds.

The 18 cities are Detroit, Baltimore, Milwaukee, Chicago, Portland, Memphis, Philadelphia, Indianapolis, Nashville, San Francisco, Denver, Seattle, Boston, New York, Los Angeles, Austin, Dallas, and Las Vegas.

We download the shape boundary files of the 2010 census tracts and the cities from https://www2.census.gov/geo/tiger/TIGER2010DP1/, accessed on July 25, 2020.

The ACS 5-year estimates at the tract level are downloaded from https://factfinder.census.gov/, accessed in November 2019.

We confirm that using the 74% of the tracts that did not change income status from the 2006–2010 ACS to the 2014–2018 ACS does not alter our conclusions.

While the 2005–2009 ACS uses the 2000 census boundary, the next ten waves of ACS use the 2010 census boundary. Because the boundaries of some tracts might change between census years, the 2000 census tracts may not be matched with the 2010 census tracts. Hence, we decide to use data from the 2006–2010 ACS to define the tract income status.

The crime rates based on this population size would overestimate the crime rates of tracts with faster population growth after 2010. We show in Section 5.3 that using quarterly numbers of crimes generates results comparable to those derived from using quarterly crime rates.

The anonymization process varies by city. For example, in Detroit, “The anonymization process systematically takes the point of the original XY coordinates and places them randomly within 180 feet along the street from the original point.” In Chicago, “The location (where the incident occurred) is shifted from the actual location for partial redaction but falls on the same block.”

The CPI-U-RS, all items, 1977–2019, is downloaded from https://www.bls.gov/cpi/research-series/home.htm, accessed on June 25, 2020.

In Online Appendix Table A4, we show that our main conclusions are robust to including the observations in which the federal and state minimum wages are not binding in the analysis, and using the highest of federal, state, and substate minimum wages as the measure of the binding minimum wage. Nevertheless, the magnitude of the estimate declines considerably, which could be attributed to the fact that other unobserved changes in local conditions are correlated with both substate minimum wages and crime rates. We notice that cities with substate minimum wages tend to have a higher income level than those without.

Tracts within a city are not necessarily in the same county. However, for the 18 sample cities, the city minimum wage rather than the county minimum wage is invariably binding when the substate minimum wage is binding for the sample periods.

To see whether the crime rates are accurately measured, we use the neighboring sample and plot the crime trends by tract income status for each city in Online Appendix Fig. A1. For Indianapolis, Las Vegas, and Dallas, we spot striking and unexpected fluctuations in crime rates. We cannot find any explanations for such changes in the police department reports. However, excluding these cities generates results consistent with the baseline estimates. See Section 5.3 for more details.

Crime statistics from 2010 are publicly available for 10 out of the 18 cities we are analyzing, Austin, Chicago, Detroit, Indianapolis, Los Angeles, Milwaukee, New York, Philadelphia, San Francisco, and Seattle.

As specification tests, we use the raw minimum wage and the logarithm of the real minimum wage for \(MW_{st}\), and use the quarterly number of crimes for \({crime\,rate}_{rt}\). The results are robust. See Section 5.3 for further details. We thank an anonymous reviewer for pointing out that minimum wage changes may affect crime reporting behaviors. For example, due to minimum wage increases, people may come to the conclusion that the benefits of reporting a crime are insufficient to justify the associated costs. However, because a considerable proportion of crime complaints are reported by 911 calls, we expect that minimum wage changes should have a minimal impact on the reporting. Direct evidence on the reporting of crimes awaits future research.

Callaway et al. (2021) emphasize the need for a stronger common trends assumption for identification when dealing with continuous treatments, particularly in analyses comparing units with higher and lower doses. In our context, since minimum wages are continuous and uniformly applied within a city—meaning all tracts face the same minimum wage in any given period—we avoid comparisons between higher- and lower-dose units. Instead, we compare low- and high-income tracts within the same city. We thank an anonymous reviewer for raising this issue.

In the neighboring sample, since we only include low- and high-income neighboring tracts, the common trends assumption implies that the neighboring tracts in one city have the same crime trends in the absence of minimum wage changes.

For example, we account for any correlation between a low-income tract and a high-income tract in the same city in a given year-quarter. We also account for any correlation between a tract in New York and a tract in Chicago in a given year-quarter. In addition, we report the p-values for the standard errors clustered at the state-low-income and year-quarter levels for the baseline estimates.

To ensure they do not confound our main effects, we construct variables for these small events, beforeEARLY, EARLY, PRE, POST, afterPOST. Here beforeEARLY, EARLY, PRE, POST, and afterPOST capture the number of small increases if \( j \le -6\), \(-5\le j \le -4\), \(-3 \le j \le -1\), \(0 \le j \le 3\), or \(j\ge 4\), respectively. In Eq. (3), \(Small_{st}\) represents these five variables for small events and their interactions with the indicator of low-income tracts. In Eq. (4), since the city-year-quarter fixed effects are controlled for, \(Small_{st}\) represents the interactions of the small events measures and the indicator of low-income tracts.

We also use the full sample for estimation and plot the estimates in Fig. A2 in Online Appendix. The patterns are generally in line with those from the neighboring sample.

The two-way fixed effects estimate is a weighted sum of the average treatment effect (ATE) in each treated cell. In our context, a treated cell is a tract in a year-quarter after a minimum wage adjustment. The weights attached to the ATEs sum to one, but some may be negative. Consequently, the fixed effects estimate of \(\gamma \) could be negative even when all the ATEs are positive but heterogeneous across tracts or time. In Online Appendix A1, we use the method proposed by de Chaisemartin and D’Haultfœuille (2020) to assess this issue in our study and find that it is not a serious concern.

From the data spanning from 2000q1 to 2023q1, we identify a total of 95 such prominent events and create 106 event-city-specific datasets. However, 10 of these are subsequently excluded due to the non-binding nature of the federal and state minimum wages in those cases.

The 2006–2010 ACS 5-year data at the city level are downloaded from https://data.census.gov, accessed on April 3, 2023.

We examine the robustness of the mechanism analysis results using alternative ACS 5-year estimates at the tract level. First, we use the 2005–2009 ACS 5-year estimates at the tract level, the earliest publicly available tract-level ACS data, instead of the data from the 2006–2010 ACS to classify low-income tracts. Second, we construct a balanced sample of tracts using the ACS 5-year estimates from 2005–2009 to 2017–2021, and merge the tract characteristics for the estimate period of \([t, t+4]\) instead of \([t-4, t]\) with the minimum wages in t. The results of the two robustness checks are reported in Online Appendix Tables A9 and A10, respectively. Despite the substantial differences in the sample composition, these results align with those in Tables 5 and 6, particularly regarding the reduction in the income gap between low- and high-income tracts in response to the minimum wage increases.

In Online Appendix A2, we perform back-of-the-envelope calculations, assuming the income effect of minimum wage changes as the sole channel through which the minimum wage influences the violent crime rate. Our estimation reveals that a one-dollar increase in total annual household income is associated with a reduction of $0.14 in total violent crime cost.

The poverty thresholds in 2010 are downloaded from https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/income-poverty/historical-poverty-thresholds.html, accessed on May 9, 2022.

The mean number of earners per household among the lowest fifth income quintile is obtained from the Current Population Survey (CPS) Annual Social and Economic (ASEC) Supplement - Household Income in 2010, https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/income-poverty/cps-hinc/hinc-05.2010.html, accessed on April 5, 2022.

References

Aaronson D, Agarwal S, French E (2012) The spending and debt response to minimum wage hikes. American Economic Review 102(7):3111–3139

Agan AY, Makowsky MD (2021) The minimum wage, EITC, and criminal recidivism. Journal of Human Resources 58(5):1712–1751

Allegretto SA, Dube A, Reich M (2011) Do minimum wages really reduce teen employment? Accounting for heterogeneity and selectivity in state panel data. Ind Relat 50(2):205–240

Anderson DA (2021) The aggregate cost of crime in the United States. The Journal of Law and Economics 64(4):857–885

Autor DH, Manning A, Smith CL (2016) The contribution of the minimum wage to US wage inequality over three decades: A reassessment. Am Econ J Appl Econ 8(1):58–99

Bárány ZL (2016) The minimum wage and inequality: The effects of education and technology. J Law Econ 34(1):237–274

Beauchamp A, Chan S (2014) The minimum wage and crime. The B.E. Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy 14(3): 1213–1235

Becker GS (1968) Crime and punishment: An economic approach. J Polit Econ 76(2):169–217

Bernasco W, Block R (2009) Where offenders choose to attack: A discrete choice model of robberies in Chicago. Criminology 47(1):93–130

Billings S, Hoekstra M (2023) The effect of school and neighborhood peers on achievement, misbehavior, and adult crime. J Law Econ 41(3):643–685

Braun C (2019) Crime and the minimum wage. Rev Econ Dyn 32:122–152

Burkhauser R, McNichols D, Sabia J (2023) Minimum wages and poverty: New evidence from dynamic difference-in-differences estimates. NBER Working Paper No. 1182

Callaway B, Goodman-Bacon A, Sant’Anna PHC (2021) Difference-in-differences with a continuous treatment. arXiv:2107.02637

Cameron AC, Gelbach JB, Miller DL (2008) Bootstrap-based improvements for inference with clustered errors. Rev Econ Stat 90(3):414–427

Campolieti M, Fang T, Gunderson M (2005) How minimum wages affect schooling-employment outcomes in Canada, 1993–1999. J Lab Res 26(3):533–545

Card D (1992) Do minimum wages reduce employment? A case study of California, 1987–89. Ind Labor Relat Rev 46(1):38–54

Card D, DiNardo JE (2002) Skill-biased technological change and rising wage inequality: Some problems and puzzles. J Law Econ 20(4):733–783

Card D, Krueger AB (1994) Minimum wages and employment: A case study of the fast-food industry in New Jersey and Pennsylvania. American Economic Review 84(4):772–793

Cengiz D, Dube A, Lindner A, Zipperer B (2019) The effect of minimum wages on low-wage jobs. Quart J Econ 134(3):1405–1454

Chalfin A (2015) Economic Costs of Crime. In: Jennings WG (ed) The Encyclopedia of Crime & Punishment. Wiley, New York, pp 1–12

Clemens J, Wither M (2019) The minimum wage and the Great Recession: Evidence of effects on the employment and income trajectories of low-skilled workers. J Public Econ 170:53–67

Damm AP, Dustmann C (2014) Does growing up in a high crime neighborhood affect youth criminal behavior? American Economic Review 104(6):1806–1832

de Chaisemartin C, D’Haultfœuille X (2020) Two-way fixed effects estimators with heterogeneous treatment effects. American Economic Review 110(9):2964–2996

Derenoncourt E, Montialoux C (2021) Minimum wages and racial inequality. Quart J Econ 136(1):169–228

DiNardo J, Fortin NM, Lemieux T (1996) Labor market institutions and the distribution of wages, 1973–1992: A semiparametric approach. Econometrica 64(5):1001–1044

Dube A (2019) Minimum wages and the distribution of family incomes. Am Econ J Appl Econ 11(4):268–304

Dube A, Lester TW, Reich M (2010) Minimum wage effects across state borders: Estimates using contiguous counties. Rev Econ Stat 92(4):945–964

Enamorado T, López-Calva LF, Rodríguez-Castelán C, Winkler H (2016) Income inequality and violent crime: Evidence from Mexico’s drug war. J Dev Econ 120:128–143

Fajnzylber P, Lederman D, Loayza N (2002) Inequality and violent crime. The Journal of Law & Economics 45(1):1–39

Fernandez J, Holman T, Pepper JV (2014) The impact of living-wage ordinances on urban crime. Ind Relat 53(3):478–500

Foley CF (2011) Welfare payments and crime. Rev Econ Stat 93(1):97–112

Fone ZS, Sabia JJ, Cesur R (2023) The unintended effects of minimum wage increases on crime. J Public Econ 219:104780

Freedman M, Owens E, Bohn S (2018) Immigration, employment opportunities, and criminal behavior. Am Econ J Econ Pol 10(2):117–151

Freeman RB (1996) Why do so many young American men commit crimes and what might we do about it? Journal of Economic Perspectives 10(1):25–42

Giuliano L (2013) Minimum wage effects on employment, substitution, and the teenage labor supply: Evidence from personnel data. J Law Econ 31(1):155–194

Glaeser EL, Sacerdote B, Scheinkman JA (1996) 05) Crime and social interactions. Quart J Econ 111(2):507–548

Gould ED, Weinberg BA, Mustard DB (2002) Crime rates and local labor market opportunities in the United States: 1979–1997. Rev Econ Stat 84(1):45–61

Hannon LE (2005) Extremely poor neighborhoods and homicide. Soc Sci Q 86(s1):1418–1434

Hansen K, Machin S (2002) Spatial crime patterns and the introduction of the UK minimum wage. Oxford Bull Econ Stat 64(Supplement):677–697

Harasztosi P, Lindner A (2019) Who pays for the minimum wage? American Economic Review 109(8):2693–2727

Hoekstra M, Sloan C (2022) Does race matter for police use of force? Evidence from 911 calls. American Economic Review 112(3):827–860

Jardim E, Long MC, Plotnick R, Inwegen Ev, Vigdor J, Wething H (2018) Minimum wage increases and individual employment trajectories. NBER Working Paper No. 25182

Kang S (2016) Inequality and crime revisited: Effects of local inequality and economic segregation on crime. J Popul Econ 29(2):593–626

Kelly M (2000) Inequality and crime. Rev Econ Stat 82(4):530–539

Kling JR, Ludwig J, Katz LF (2005) Neighborhood effects on crime for female and male youth: Evidence from a randomized housing voucher experiment. Quart J Econ 120(1):87–130

Krivo LJ, Lyons CJ, Vélez MB (2021) The U.S. racial structure and ethno-racial inequality in urban neighborhood crime, 2010–2013. Sociology of Race and Ethnicity 7(3): 350–368

Lee DS (1999) Wage inequality in the United States during the 1980s: Rising dispersion or falling minimum wage? Quart J Econ 114(3):977–1023

Lin M (2008) Does unemployment increase crime? Evidence from U.S. data 1974–2000. Journal of Human Resources 43(2): 413–436

Lochner L, Moretti E (2004) The effect of education on crime: Evidence from prison inmates, arrests, and self-reports. American Economic Review 94(1):155–189

Ludwig J, Duncan GJ, Hirschfield P (2001) Urban poverty and juvenile crime: Evidence from a randomized housing-mobility experiment. Quart J Econ 116(2):655–679

Meer J, West J (2016) Effects of the minimum wage on employment dynamics. Journal of Human Resources 51(2):500–522

Merton RK (1938) Social structure and anomie. Am Sociol Rev 3(5):672–682

Montolio D (2018) The effects of local infrastructure investment on crime. Labour Econ 52:210–230

Morenoff J0D, Sampson RJ, Raudenbush SW (2001) Neighborhood inequality, collective efficacy, and the spatial dynamics of urban violence. Criminology 39(3):517–558

Neumark D, Salas JM, Wascher W (2014) Revisiting the minimum wage-employment debate: Throwing out the baby with the bathwater? ILR Rev 67(SUPPL):608–648

Neumark D, Wascher W (2002) Do minimum wages fight poverty? Econ Inq 40(3):315–333

Neumark D, Wascher W (2003) Minimum wages and skill acquisition: Another look at schooling effects. Econ Educ Rev 22(1):1–10

New York Police Department (2019) NYPD complaints incident level data footnotes. https://data.cityofnewyork.us/api/views/qgea-i56i/files/b21ec89f-4d7b-494e-b2e9-f69ae7f4c228?download=true &filename=NYPD_Complaint_Incident_Level_Data_Footnotes.pdf. accessed on March 27, 2019

Oster A, Agell J (2007) Crime and unemployment in turbulent times. J Eur Econ Assoc 5(4):752–775

Pacheco GA, Cruickshank AA (2007) Minimum wage effects on educational enrollments in New Zealand. Econ Educ Rev 26(5):574–587

Papachristos AV, Brazil N, Cheng T (2018) Understanding the crime gap: Violence and inequality in an American city. City & Community 17(4):1051–1074

Peterson RD, Krivo LJ (2010) Divergent Social Worlds: Neighborhood Crime and the Racial-Spatial Divide. Russell Sage Foundation

Sabia JJ, Burkhauser RV, Hansen B (2012) Are the effects of minimum wage increases always small? New evidence from a case study of New York State. Ind Labor Relat Rev 65(2):350–376

Schmidheiny K, Siegloch S (2021) On event study designs and distributed-lag models: Equivalence, generalization and practical implications. IZA Discussion Paper No. 12079, Institute of Labor Economics

Schnepel KT (2016) Good jobs and recidivism. Econ J 128:447–469

Sharkey P (2018) Uneasy Peace: The Great Crime Decline, the Revival of City Life, and the Next War on Violence. W.W. Norton & Company, New York

Shaw C, McKay H (1942) Juvenile Delinquency and Urban Areas. University of Chicago Press

Smith EL, Cooper A (2013) Homicide in the U.S. known to law enforcement, (2011) Technical Report NCJ 243035, Bureau of Justice Statistics. U.S, Department of Justice

Soares RR (2004) Development, crime and punishment: Accounting for the international differences in crime rates. J Dev Econ 73(1):155–184

Sun L, Abraham S (2021) Estimating dynamic treatment effects in event studies with heterogeneous treatment effects. Journal of Econometrics 225(2):175–199

Census Bureau US (2012) United States Summary: 2010, Chapter 2, Population and Housing Unit Counts: 2010. U.S, Government Printing Office, Washington, DC, p 2012

Vaghul K, Zipperer B (2016) Historical state and sub-state minimum wage data

Wheeler AP, Herrmann CR, Block RL (2021) Micro-place Homicide Patterns in Chicago, 1965–2017. Springer

Yang CS (2017) Local labor markets and criminal recidivism. J Public Econ 147:16–29

Acknowledgements

We thank editor Shuaizhang Feng and two anonymous reviewers for very helpful comments and suggestions.

Funding

Li Li received support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (72103065).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Responsible editor: Shuaizhang Feng.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, L., Liu, H. The minimum wage and cross-community crime disparities. J Popul Econ 37, 44 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-024-01023-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-024-01023-w