Abstract

This paper examines the labour market and health effects of a non-contributory long-term unemployment (LTU) benefit targeted at middle-aged disadvantaged workers. To do so, we exploit a Spanish reform introduced in July 2012 that increased the age eligibility threshold to receive the benefit from 52 to 55. Our results show that men who were eligible for the benefit experience a reduction in injury hospitalisations by 12.9% as well as a 2 percentage points drop in the probability of a mental health diagnosis. None of the results are significant for women. We document two factors that explain the gender differences: the labour market impact of the reform is stronger for men, and eligible men are concentrated in more physically demanding sectors, like construction. Importantly, we also find evidence of a program substitution effect between LTU and partial disability benefits. Our results highlight the role of long-term unemployment benefits as a protecting device for the (physical and mental) health of middle-aged, low-educated workers who are in a disadvantaged position in the labour market.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Most of the research on the welfare effects of unemployment insurance has focused on the potential moral hazard effects of unemployment benefits and the extent to which they discourage labour supply (Schmieder and Von Wachter 2016). Thus, the optimal design of unemployment insurance should equalise its costs, as measured by the magnitude of moral hazard, and the benefits, in terms of consumption smoothing (Chetty 2006). However, there are other potential and unexplored costs and benefits of unemployment insurance that should be documented and incorporated into the optimal design models.

While the negative impact of becoming unemployed on mental health has been extensively documented (Browning and Heinesen 2012; Cygan-Rehm et al. 2017; Farré et al. 2018; Schaller and Stevens 2015), the role of benefits as mediators in this relationship, either reinforcing or reducing it, is unclear.

We fill in this gap in the literature by providing new evidence on the extent to which a non-contributory benefit for long-term unemployed workers affects their health. We exploit a reform implemented in Spain in July, 2012, that created exogenous variation in access by increasing the eligibility age from 52 to 55 years old. Thus, individuals turning 52 just before the reform (born in the first semester of 1960), were eligible while those turning 52 right after were not (born in the second semester of 1960). We compare these two groups of individuals in the same cohort. We also incorporate in the analysis neighbouring cohorts so as to eliminate any differences between individuals born at the beginning and end of the year.

We focus on several health outcomes, such as hospitalisations, mental health diagnosis, and self-reported mental health, as well as on the labour market status of affected workers. Our results show that men (women) in the last eligible cohort are 3.7 (2.5) percentage points more likely to receive the benefit. On the other hand, individuals in the cohort that loses eligibility are more likely to leave the labour market and to receive other unemployment benefits as well as disability benefits. With respect to health outcomes, the last cohort of eligible men experiences a reduction in injury hospitalisations of 12.9% and they are significantly less likely to be diagnosed with a mental health problem. Furthermore, their self-assessed health is significantly better than those that lost access to the benefit and they significantly score lower in the EURO-D depression scale.

The gender dimension becomes important in interpreting those results as none of the previous health impacts are significant for women. These gender differences are explained by the fact that men prove to be more affected by the reform as well as by their concentration in sectors that are more physically demanding, such as construction.

The same reform has been previously studied by Domènech-Arumí and Vannutelli (2021). However, they use a different identification strategy and they focus only on the labour market impacts. Thus, we make three contributions with respect to this previous paper: first, we estimate both a within and between cohort model that allows us to more precisely take into account any potential labour market trends affecting these cohorts; second, we incorporate as outcomes several health variables; and, finally, we show evidence of program substitution effects, particularly with the disability insurance system.Footnote 1

Our paper related to several strands of the literature. First, we contribute to the literature that studies the effects of unemployment insurance (UI) on health. For the US, Cylus et al. (2015) show that the negative relationship between unemployment and poor health is milder in states where the generosity of unemployment benefits is higher. In the German context, a reduction in the generosity of unemployment benefits increases poor self-reported health among unemployed individuals (Shahidi et al. 2020).

Two other papers analyse those effects using detailed administrative data. Kuka (2020) exploits the exogeneity of US state UI laws to show that more generous systems lead to increased health insurance take-up, better self-reported health, and more preventive healthcare use. Ahammer and Packham (2023) use an extension of UI in Austria to show that nine additional weeks of benefits lead to fewer opioids and antidepressant prescriptions for women and a reduction in disability claims. This is achieved through an improvement of the job match for affected women. However, they find little evidence of health effects for men.

More specifically, our paper contributes to the above-reviewed literature in several dimensions. First, while most other papers deal with the endogeneity problem of unemployment benefits and health status by exploiting changes in the generosity of the system (either in the amount of the benefit or in their duration), we are able to focus on the extensive margin by comparing similar eligible and non-eligible individuals that only differ in their month of birth. With this comparison, we explore both the short- and mid-term effects of LTU benefits, as we follow them up to three years after being eligible. Second, we focus on a specific group of the population, disadvantaged middle-aged workers, with greater risks of suffering from poor health. From a policy perspective, the focus on this particular population group is important to understand the extent to which benefit entitlement interacts with their health status, healthcare use, and government expenditures in the medium run.

By focusing on a policy that directly affects low-educated and low-skilled middle-aged workers, our paper also speaks to the recent literature on the so-called “deaths of despair”. Case and Deaton (2017) show that there has been an increase in morbidity and mortality in middle-aged men in the US that can be attributed to a “cumulative disadvantage” process of (mainly) poor labour market conditions, coupled with a situation of general economic and socioeconomic decline. The authors argue that such disadvantages will not be reversed in the short term. In this paper, we provide evidence on the extent to which social programs (i.e. LTU benefit) can protect the health of middle-aged disadvantaged workers who have suffered from a “cumulative disadvantage” in the labour market.

Another strand of the literature where this paper contributes focuses on the relation between UI and other welfare programs, such as disability insurance (DI). Previous research finds contradictory results. For instance, Petrongolo (2009) shows that tightening access to UI in the UK increased DI uptake, while tightening access to DI in Austria has also been found to increase UI uptake (Staubli 2011). On the other hand, Mueller et al. (2016) found no significant effect of extending UI benefits on DI uptake in the US during the Great Recession. In a setting closer to ours, Inderbitzin et al. (2016) studied an Austrian reform that extended the duration of regular UI benefits for workers older than 50 years old. The authors found evidence of program substitution from workers closer to age 60 who previously used DI as bridge to retirement. At the same time, they also report evidence on program complementarity, where workers closer to age 50 could now combine first UI and then DI benefits as a bridge to retirement. Domènech-Arumí and Vannutelli (2021) show evidence of program substitution from LTU benefit to other unemployment assistance programs, but fail to examine the effects on DI. Our findings suggest a significant program substitution effect between LTU benefits and partial disability benefits, but no relation with total disability benefits. Our results reinforce the need to take into account the potential spillovers of UI reforms on other welfare programs.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2 describes the LTU benefit reform. Section 3 describes the data sources and the empirical strategy. Section 4 describes the results. Section 5 provides a set of robustness checks, and Section 6 concludes with a discussion of the main findings and the implications.

2 The Spanish labour market, long-term unemployed (LTU) benefits, and the 2012 reform

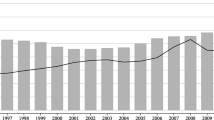

The Spanish economy was particularly hard hit by the 2008 Great Recession, which was exacerbated by the burst of its own domestic housing bubble. This led to a significant decline in GDP, with a 9% drop between 2008 and 2013. The recession resulted in high levels of private and public debt and a surge in unemployment, particularly driven by job losses in the construction sector. The unemployment rate rose from a record low of 8% in 2007 to 25% in 2012, more than double the European Union average (Eurostat). Several factors have been suggested to explain this increase, such as the existence of a dual labour market with a large gap in effective employment protection between temporary and permanent contracts, which led to a strong destruction of temporary jobs (Bentolila et al. 2012). Therefore, the high prevalence of temporary jobs in the Spanish economy largely contributed to the rapid increase in the unemployment rate during this period.

In this context, In July, 2012, the Spanish government passed a reform to “guarantee fiscal stability and increase the competitiveness of the Spanish economy” (Real Decreto-ley 20/2012) which included several measures to guarantee fiscal stability, mainly tax increases, and public expenditure cuts. Among those, there was an increase in the eligibility age for the non-contributory long-term unemployment (LTU) benefit from 52 to 55 years old. Therefore, individuals turning 52 right before the reform (i.e. born in the first semester of 1960) were eligible for the benefit, whereas those turning 52 right after the reform (born in the second semester of 1960) were not eligible until they turned 55, in 2015. Crucially, eligible individuals that were granted access to the program before the reform were grandfathered in and therefore did not lose the LTU benefit even if they were younger than the new minimum age. Our identification strategy explained in detail in Section 3 compares these two groups of individuals vis-à-vis the same difference in neighbouring cohorts to estimate the labour market and health effects of being entitled to the benefits. Importantly, there are no major changes in the labour market happening at the same time as our reform and affecting the same group of individuals.Footnote 2

The scheme, funded by the Social Security, provides unemployment assistance to middle-aged workers unable to find a bridge job until they reach retirement age (65 years old at the time). Apart from the age threshold, individuals must have exhausted their unemployment insurance benefits from the Social Security (maximum duration of two years (SEPE 2019)) to be eligible. Thus, the LTU program is designed as a last resort option for disadvantaged workers approaching retirement. The benefit is provided by the Social Security; it amounts to 426€ per month during our sample period, it can be received until retirement, and cannot be combined with any other salary or Social Security benefit.Footnote 3 Unemployed individuals without Social Security subsidies can alternative access welfare benefits (i.e. minimum guaranteed incomes) managed by the regions. The availability, generosity, and duration of these benefits depend on the region, but their scope is far more limited than that of the Social Security benefits.Footnote 4

The LTU subsidy is designed to serve as a minimum income scheme for middle-aged unemployed low-skilled workers who are unable to find a job. These workers might have serious difficulties in finding a job if they are in a jobless situation from age 50. This is also the case in the Spanish context: in 2012, 42% of unemployed workers aged 50–64 had been unemployed for more than two years, which is a much higher rate than the 30% for the overall population (Labour Force Survey).

The data shows that this benefit scheme often acts as an absorbing state until retirement, as 17.2% of those in the scheme aged 52–65 will be receiving a retirement pension in their next labour market transition, compared to 7.3% for the other unemployed and 8.4% for the employed in the same age group (MCVL,Footnote 5 Table A2 in Appendix A).

Recipients of the LTU benefits are less educated than those in employment (35.6% with less than primary education vs. 21%) but have similar educational levels as the other unemployed (Table A3 in Appendix A). Those educational disparities are translated into different distributions across sectors of activity (Table A4 in Appendix A): before entering the LTU scheme, men were concentrated in construction (31.6%), a sector where low-educated workers are strongly overrepesented (with 61% of workers having primary or less education as compared to 43% for the average worker of the same age [Table A5 in Appendix A]). Additionally, salaries in this sector are around 250 euros less than the average salary (Table A1 in Appendix A). On the other hand, women were mostly employed in manufacturing (25.4%, Table A4 in Appendix A), a sector where also lower-educated women are overrepresented, but have a salary somehow higher than the average women in other sectors (Table A1 in Appendix A). We also observe much more interrupted labour market histories for workers entering the LTU scheme: both men and women have spent more time in unemployment in the four years preceding the receipt of the benefit (Table A6 in Appendix A) and men accumulated an average of 4.4 different employment contracts during 2008–2011, which is significantly larger than the number for the rest of the unemployed (3.4) and the employed (1.8).

Therefore, workers accessing the LTU benefit are a specific group of the population that is disadvantaged in several dimensions: they are low-educated workers relatively concentrated in specific sectors (men in construction and women in manufacturing), and with a relatively poor and unstable labour market trajectories before joining the scheme. This disadvantage seems more pronounced in the case of men, whose main occupational sector (construction) offers significantly lower salaries.

3 Methods and data

We focus on the labour market and physical and mental health outcomes and use a combination of survey data and administrative registers.

3.1 Labour market outcomes

To analyse the effect of being eligible to LTU benefits on labour market outcomes, we use the Continuous Sample of Working Lives (MCVL, Muestra Continua de Vidas Laborales), which is an administrative dataset that contains a representative random sample of 4% of all individuals who contribute to the Spanish Social Security system. For each individual, we have information on their lifetime labour market participation, including the duration of their employment/unemployment spells, the economic sector, and other characteristics of each employment contract or social security benefit (including unemployment insurance, unemployment subsidies, and disability and retirement benefits). It also includes information on several socioeconomic characteristics of each individual such as age, gender, and education.

We select a sample of individuals born between 1960 and 1962 so that they were aged between 49 and 52 at the time of the reform (2012) and follow them from 2009 to 2014. Our sample includes 72,082 individuals and a total of 431,057 person-year observations.

Our identification strategy exploits the reform that increased eligibility to the LTU benefit from 52 to 55 years old, to estimate the effect of LTU subsidy eligibility on labour market outcomes. As explained above, we compare individuals turning 52 right before the introduction of the reform (born in the first semester of 1960), which were eligible for the benefit in 2012 (our “treatment” group) with individuals turning 52 right after the reform (born in the second semester of 1960), who were not eligible for the benefit until 2015 when they turned 55 (our “control” group). Note that we define as our “treatment” group those individuals that had access to the LTU benefit at the earlier age of 52 and were not affected by the reform. Thus our “control group” are individuals that only had access to LTU benefit at the later age of 55 years old, because of the reform.Footnote 6

To control for any differences in the outcome variables between individuals born at the beginning and end of the year, we include as additional controls the closest cohorts of non-eligible individuals, born in 1961 and 1962, which could only apply from 2016 when they turned 55. The addition of these other cohorts is important as the literature has shown that the month of birth may affect health outcomes, either directly (Buckles and Hungerman 2013; Costa and Lahey 2005; Rietveld and Webbink 2016) or through the increase in education (Angrist and Keueger 1991), which might also affect health outcomes (Bellés-Obrero et al. 2022).

Therefore, if the reform had an impact on labour market outcomes, we should see differential changes in the outcomes of those born in the 1st semester (“treatment” group eligible for LTU benefit) compared to those born in the 2nd semester (“control” group non-eligible for LTU benefit) after the reform (from 2012) and for the cohort of 1960 but not for the 1961–1962 control cohorts.Footnote 7 In Table 1 below we provide a visual summary of our identification strategy.

Thus, our identification strategy relies on a triple differences-in-differences (DDD) model exploiting variation by cohort, semester of birth, and time, similarly to specifications used in previous literature (Berck and Villas-Boas 2016; Gruber 1994) and is estimated using the following equation:

where \({Cohort1960}_{i}\) equals 1 if individual i was born in 1960 and 0 otherwise (born in 1961–1962); \({Semester1}_{i}\) equals 1 if individual i is born from January to June, and zero if born from July to December; \({After2012}_{t}\) equals 1 for observations from the year 2012 onwards; \({year}_{t}\) are year fixed effects; and \({province}_{p}\) are province fixed effects (50 provinces). Employment status is measured by three dependent binary variables.

We run a linear probability model separately for each of the following six mutually exclusive employment statuses which are measured as dummy variables (\({y}_{i,t})\): LTU benefit, employed, unemployed (receiving benefits from unemployment insurance or other unemployment subsidies), out of the labour market (neither working in a formal job nor receiving any Social Security benefit),Footnote 8partial disability (receiving benefits of 55–75% of previous wages), and total disability (100% of previous wages).

Our main parameter of interest is \({\beta }_{ 7}\), which identifies the DDD impact of being eligible to the LTU benefit on labour market status. That is the difference between those born before and after July, in cohort 1960 (as compared to those born in the control cohorts 1961–1962), before and after the reform. Standard errors are clustered at the province level (50 provinces).

3.2 Physical and mental health outcomes

In order to explore the effects of the reform on health outcomes, we use three different datasets: two of them are administrative records for hospitalisation and primary care data while the third one is a survey.

3.2.1 Hospitalisations

We use registered data of all hospitalisations that occurred in Spanish hospitals between 2009 and 2014 (Instituto Nacional de Estadística—INE). Each hospitalisation includes information on the date of birth, gender, and province of residence of the patient, as well as main diagnoses (following the International Classification of Diseases, ICD-9-CM). As before, we restrict observations of hospitalisations from individuals born in 1960–1962 which includes a total of 852,577 registered hospitalisations. We aggregate them by province,Footnote 9 cohort of birth, semester of birth, and year. Since we do not observe the employment status of the hospitalised individuals, our identification exploits exposure to the reform by cohort and semester of birth relying on intention to treat estimates, and it is based on the following DDD model:

Independent variables are defined as those in Eq. (1). We create a dependent variable, \(Hospitalisation rate\), which measures the number of hospitalisations per 1000 individuals for each cohort (c), semester of birth (s), province (p), and year (t), during the period 2009–2014.Footnote 10 We include weights of the population born in 1960–1962 in each province by July, 2012 (source: INE). Standard errors are clustered at the province level.

We also group hospitalisations by main diagnoses using the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-9) and, following previous literature, we pay particular attention to the work-related diagnosis as they are more likely to be impacted by the change in LTU benefit entitlement. Therefore, we focus on mental health, injuries,Footnote 11 as well as the most prevalent conditions in our sample: digestive, musculoskeletal, and circulatory diseases. We also used cancer as a placebo test as it should not be affected by the reform (Table 3).

As before, \({\beta }_{7}\) is our parameter of interest capturing the effect of being eligible to the LTU benefit on hospitalisations.

3.2.2 Mental health diagnoses

Hospitalisations represent a relatively extreme outcome which serves as a proxy for severe health shocks. However, it is reasonable to think that the reform will have stronger effects on milder health outcomes. Thus, in this section we focus on mental health diagnosis at primary care centres. We use data from registered primary care clinical centres provided by the Spanish Minister of Health (Base de datos clínicos Atención Primaria—BDCAP). The BDCAP is a sample of representative individuals registered with a primary care doctor in the Spanish National Health Service and it includes information on the health conditions diagnosed at these facilities. Health conditions are classified following the International Classification of Primary Care—2nd Edition (CIAP2).

We select the same sample cohorts as before (born in 1960–1962) and we include regions that have data from before the reform (Aragon, Balearic Islands, Canary Islands, Catalonia, Galicia, and Basque Country). Our final sample includes 37,690 individuals followed from 2011 to 2014, amounting to a total sample of 150,760 person-year observations.Footnote 12

We estimate the same model as in Eq. (1) above, but the dependent variable equals 1 if individual i has been diagnosed with a mental health condition in year t, and zero otherwise. We fit a linear probability model using sample weights that are provided by BDCAP to make the sample representative at the regional level.

3.2.3 SHARE data

Finally, we use survey data from the Survey of Health Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) to understand whether the reform had an impact on other dimensions of health: self-assessed health and mental health. SHARE is a multidisciplinary panel database with information on health and other socioeconomic variables of European individuals aged 50 or older and is representative at the country level. We use the subsample for Spain for wave 5 (2013) and wave 6 (2015). We select the same cohorts as before and get a sample of 713 observations.

As SHARE data is not available for the years before the reform,Footnote 13 our identification strategy is a bit different from before and relies only on post-reform data:

where \({Cohort1960}_{i}\) equals 1 if the individual was born in 1960, zero otherwise; \({Semester1}_{i}\) equals 1 if the individual is born from January to June, zero otherwise; and \({year}_{t}\) are year fixed effects.

We use three dependent variables \({y}_{i,t}\) capturing three dimensions of health: self-reported health status (from 1 excellent to 5 poor), EURO-D depression scale (from 0 not depressed to 12 very depressed), and any antidepressant weekly (a binary variable indicating whether the individual takes any antidepressant at the weekly level).

In this case, our identification assumption is a bit different and implies that there are no health differences between those individuals born in the 1st and 2nd semesters that are cohort specific other than those that could have been imposed by the reform. Thus, in the absence of the reform, we should observe the same health differences between those born in the 1st and 2nd semester for the 1960 cohort as for the 1961–1962 ones. Our parameter of interest is \({\beta }_{3}\). We estimate Eq. (3) using the following models according to the type of dependent variable: an ordered probit for self-reported health status, a negative binomial model for the EURO-D depression scale, and a LPM for any antidepressant weekly.

4 Results

4.1 Effect on labour market outcomes

The DDD results displayed in Table 2 show that there was a significantly higher probability of receiving the LTU benefit for those eligible with respect to those ineligible (affected by the raise in the minimum age). This is greater for men, 3.7 percentage points, than for women, 2.5 percentage points. Simultaneously, the probability of being out of the labour market fell by 1.4 percentage points (pp) for eligible men and by 1.3 pp for eligible women. Eligible men are also 1.1 pp less likely of receiving any other benefit (including unemployment insurance) than those without access to the LTU system. Interestingly, both men and women that had access to the unemployment subsidy scheme are 0.3 pp less likely to enter the partial disability program. Therefore, individuals that were not allowed into the LTU system managed to substitute benefits through the disability program.

To check the existence of parallel trends before the reform as well as to understand the timing of the effects post-reform, in Fig. 1 we decompose the triple difference coefficient and include interactions of the cohort and semester of birth with each year dummy (Eq. B1, Appendix B) in an event-style model. The plotted coefficients represent the differences between the eligible and non-eligible groups (defined by cohort and semester of birth) for every year before and after the reform. We set 2011 as the base category because none of the cohorts could access the benefit system at that time. From 2012, only those born in the first semester of 1960 were eligible for the LTU subsidy.

Triple difference (DDD) estimates for the probability of each employment status over time. Notes: These figures plot the coefficients (and 95% confidence intervals) of the interactions between the double difference cohort-semester and the year dummies, which results from the decomposition of the triple difference (DDD) coefficient for each employment status, as further explained in Eq. (B1) of Appendix B. We set the year before the reform (2011) as the base category. In (a), note that the pre-2012 coefficients for LTU benefit are flat zeros because none of the cohorts could access the LTU benefit then since they were all younger than 62

We see in panel A of Fig. 1 that, as expected, eligible individuals have a higher probability of receiving the benefits from 2012 and that this effect remains constant over time. Figure 1 also confirms that eligible individuals who received the LTU benefit before the reform were grandfathered in and did not lose it after the rise in the eligibility age. In panel C we corroborate that receiving other unemployment benefits is a significant alternative to the LTU benefit, particularly during the first year after the introduction of the reform.

Being out of the labour market also seems like an important alternative for ineligible individuals, although this differs slightly by gender. On the one hand, the effect on being out of the labour market remains constant or slightly increases for women over time. For men, however, this effect seems to shrink over time. At the same time, the probability of formal employment seems to diminish over time for those eligible for the LTU by two years after eligibility (p < 0.10). Furthermore, results by type of contract (permanent vs. temporal) show a significant decrease in the probability of permanent employment by 1.5 pp for men eligible for LTU benefit, not for women (Fig. A1 in Appendix A). Overall, this suggests that ineligible men are more able than ineligible women to find a job during the second and third years after the reform. Lastly, both men and women that are prevented from accessing the LTU have higher and significant probabilities of entering the partial disability system.

Although we are unable to test the impact of the reform on the informal labour market, it seems likely that ineligible individuals could have taken informal jobs given the high incidence of this type of jobs in Spain (Hazans 2011).

Finally, using the same specification we explore the impact of the reform on monthly income. The data comes from Social Security contributions (MCVL) so the definition of income is monthly formal income, which can come from employment or any other Social Security Benefit, including the LTU. Our results show that there is no significant effect of the reform on the average monthly income (Fig. A2, Appendix A) because, while the main alternative to LTU benefit (out of labour market) implies no observed income, the other two alternatives (formal employment and unemployed with another benefit) imply an income that is considerably higher (on average) (1520€ and 635€) than the LTU benefit (426€).Footnote 14 Therefore, the net effect of the reform on the average salary is not significantly different from zero.

4.2 Effect on health outcomes

4.2.1 Effect on hospitalisations

Looking at the descriptive statistics in Table 3, we can see that before the reform, in 2011, the mean hospitalisation rate from any diagnosis was 68 per thousand individuals. For the outcomes analysed in this paper, hospitalisation rates were 3 and 4.6 per thousand individuals for mental health and injuries, respectively. These numbers represent 4% and 7% of the total number of hospitalisations.

The results of the triple difference model are reported in Table 4, and we can see that none of the coefficients of interest is significant. To explore the effects for the different diagnoses separately, in Fig. 2 we plot the DDD coefficients for the main groups of diseases and gender. As can be seen, the only group that has a significant negative coefficient is hospitalisations due to injuries. Furthermore, the impact comes entirely from eligible men who had access to the subsidy, with a drop of 0.8 hospitalisations per thousand individuals. This effect implies a reduction of injury hospitalisation rates by 12.9% for men. The coefficients for the other diagnoses are not significant. Note that hospitalisations due to cancer can be used as a placebo test as they should not be affected by the reform, which is exactly what we observe in Fig. 2.

DDD estimates per group of disease of main diagnosis (ICD-9). Notes: Coefficients (and 95% confidence intervals) from the triple interaction (\({cohort1960}_{c} \times {semester1}_{s} \times {after2012}_{t})\) of the triple difference (DDD) model for hospitalisation rates (Eq. (2)). The model was run separately per each ICD-9 diagnosis group and gender. Standard errors are clustered at the province level

In Fig. 3 we plot the coefficients of an event model in which we interact the cohort and semester of birth treatment with the year dummies, setting 2011 as the baseline category. We show the results for men and women separately, for total hospitalisations, and for the two main diseases of interest: mental health and injuries.

Impact of the LTU benefit over time on hospitalisations rates (per 1000 inhabitants). Notes: These figures plot the coefficients of the interactions between the double difference cohort-semester and the year dummies, which results from the decomposition of the triple difference (DDD) coefficient for hospitalisation rates, as explained in Eq. (B2) of Appendix B. We set the year before the reform (2011) as the base category. Robust standard errors clustered at the province level

There is evidence of parallel trends for both genders and for the three types of hospitalisations. Furthermore, we can see that the reduction in injury hospitalisations for eligible men becomes larger over the three years after the reform. This reduction is driven by provinces with a higher unemployment rate for those aged 50–54 years. These are the provinces with a potentially higher share of LTU benefits recipients. In particular, we find a significant drop in injury hospitalisations in provinces within the two highest tertiles of the 50–54 unemployment rate, and no effect in the provinces within the lowest tertile (Fig. A3 in Appendix A). At the highest tertile of unemployment, even mental health and total hospitalisations were reduced for LTU eligible men. The same effect on injuries is not observed in the case of women. This is consistent with a smaller effect of the reform on the probability of receiving the subsidy for women and with the fact that men in the LTU scheme come from more physically demanding sectors, such as construction.

The reduction in injuries for eligible men can be explained by at least two factors: i) a compositional change in the type of employment, with eligible men being able to avoid more risky jobs and moving towards safer jobs with less injuries or ii) eligible men simply working less. Unfortunately, our data does not allow to precisely distinguish which of these two channels is more relevant, since linked data on labour market outcomes and hospitalisations is not available in Spain. However, in Table A8 of Appendix A, we run the same triple difference model but calculating the hospitalisation rates per employed individual instead of per individual. We still observe a significant drop in injuries per employed individual, which cannot be attributed to a reduction in the probability of working (as this is kept fixed in the hospitalisation rate indicator). Therefore, we conclude that the effect is not only driven by a drop in the probability of working but also (to a certain extent) by a compositional change in the type of employment.

Overall, the results for mental health hospitalisations are not significant for either gender. However, we do detect a significant reduction in mental health hospitalisations for eligible men eligible living in provinces more exposed to the reform (Fig. A3, Appendix A). The lack of effects is reasonable given the fact that hospitalisations represent an extreme outcome in cases of mental health disease. In the following section, we explore the effects on less extreme mental health outcomes such as diagnoses from primary care register data and self-reported mental health.

4.2.2 Effect on mental health diagnoses

Now we use primary care register data to understand whether the reform brought about any changes in the probability of being diagnosed with a mental health condition by the general practitioner. Table 5 reports the results of the triple difference model and we can see that there is a negative and significant coefficient only for eligible men. Thus, men who were eligible for the LTU benefit experienced a significant drop of 2 percentage points in their probability of being diagnosed with a mental health condition at a primary care centre. As before, the coefficient is not significant for women. Fig. A4 in Appendix A plots this effect descriptively and provides reliability on the parallel trends assumption.

4.3 Effect on other health outcomes—SHARE data

Table 6 reports the results for the self-reported health outcomes using SHARE data. The first three columns correspond to an ordered probit model for self-reported health ranging from 1 (excellent) to 5 (poor). We can see that the interaction coefficient shows a negative and significant coefficient (at 10%) for the case of men, indicating that men eligible for the LTU benefit report better self-assessed health status.

Columns 4 to 6 show the results of a negative binomial model for the EURO-D depression scale as the dependent variable, which is again a self-reported outcome but focuses on mental health. We can see that men eligible for the LTU benefit report having significantly (at 10%) better mental health. As with the other outcomes analysed in the paper, the coefficient for women is insignificant. Finally, concerning the consumption of antidepressants (columns 7 to 9), none of the coefficients is significant.

As explained above, in this case, the only available data corresponds to the post-reform period. Thus, our identification strategy assumes that any difference in mental health between individuals in the first and second semesters of 1960 and those in 1961 and 1962 should be only due to the reform. To provide some support for the fulfilment of this assumption, we run placebo estimates using data from the waves before the reform was introduced (wave 1 in 2004 and wave 2 in 2007) and estimate the same model (Table A9 in Appendix A). In these placebo tests, we compare individuals aged 53 in wave 1 (used as the “fake” treatment group) and individuals aged 51 and 52 (used as the control group). None of the placebo models results in significant coefficients for men. Thus, we believe that these placebo results provide evidence that the differential effects for individuals born in the 1st semester for the 1960 cohort arise as a result of the reform.

5 Robustnes checks

5.1 Pre-trends and falsification tests

In Fig. A5 of Appendix A, we run a parallel trends check for the labour market outcomes with information going back to 2006. We show that there is no evidence of significant pre-trends for any of the outcomes under study. In Fig. A6 we run falsification tests, using alternative treatment years from 2007 to 2011, before the reform was implemented. None of the falsification tests shows significant results.

5.2 Using only 1961 as control cohort

We run a robustness check using only the most neighbouring cohort (1961) as the additional control cohort. Results for both labour market (Fig. A7 of Appendix) and health outcomes (Fig. A8 and Table A10 of Appendix A) remain very similar to our baseline model. Only the SHARE results are losing the previously weak significance, most probably as a result of lower statistical power due to smaller sample sizes (Table A11 in Appendix A).

5.3 Age dynamics

In order to make sure that our results are not affected by age dynamics, we have plotted the evolution of the probability of LTU benefit reception and unemployment by cohort over age (Figs. A9 and A10 in Appendix A). There is a big jump in the probability of LTU benefit reception (and a drop in unemployment) from age 52 only for those born in the 1st semester in the 1960 cohort, but not in the control cohort 1961–1962. This alleviates the concerns about potential confounding age dynamics. Still, we implement the following robustness checks: First, we run our baseline triple difference-in-difference model additionally controlling by age in months linearly (Table A12 in Appendix A) and by age in months fixed effects (Table A13 in Appendix A). Second, we run a triple difference-in-difference model comparing the same treated and control cohorts but, instead of over the same years, over the same ages (from 49 to 53). In this model, the triple interaction measuring the effect of being eligible to the LTU subsidy is Cohort 1960 × Semester 1 × Age 52 or older (See Table A14 in Appendix A). Results are very similar both in terms of coefficient size and significance levels to those of our baseline model.

6 Discussion

This paper studies the effects of long-term unemployment (LTU) benefits by exploiting a reform that increased the age eligibility threshold (from 52 to 55) and was introduced in Spain in July, 2012. We first document the impact of being eligible to LTU benefits on labour market outcomes and then move on to explore the impacts on several health outcomes, such as hospitalisations, mental health diagnoses, and self-reported health. To do so, we use a combination of register and survey data and employ a within- and between-cohort identification strategy.

Although there is extensive literature focusing on the welfare effects of unemployment benefits on labour supply and consumption, there is limited evidence addressing the potential health effects. Our study is particularly interesting because the scheme is designed as a last resort program targeted at a subgroup of the population that is disadvantaged in several dimensions and has poor prospects of returning to the formal labour market. Recipients in our sample have a background of relatively poor employment trajectories and vulnerable social conditions, which increases the risks of suffering from significant negative health shocks.

We first show that eligible individuals have a higher probability of receiving the benefits, 3.7 percentage points for men and 2.5 for women, compared to those that lose access to the scheme and are mostly pushed out of the formal labour market. Of course, given the high rate of informal jobs in Spain, it seems likely that some of these individuals will relocate to the informal market, but we are not able to quantify those effects in our data.

Even if we use a different methodology, our results are in line with those reported in Domènech-Arumí and Vannutelli (2021), that find a significant impact of the reform on labour market exit. However, we additionally show that the reform had an impact on health outcomes and it also generated program substitution effects towards the partial disability insurance program.

When looking at health outcomes, we find a reduction in injury hospitalisations of 12.9% for eligible men, as well as a significant reduction in the probability of being diagnosed with a mental health problem. Using survey data, we also report better self-reported health and lower EURO-D scale values for those men that can access the program. We do not find any significant result in any of the outcomes for women.

Our results differ from those of Kuka (2020) for the US who find an increase in preventive healthcare use and higher insurance take-up rates as a result of the receipt of more generous unemployment benefits. However, Spain has a universal healthcare system, so insurance take-up rates will be unchanged as coverage is independent of the labour market and benefit receipt status. Furthermore, our results differ from those in Ahammer and Packham (2023) that report an improvement in mental health for women who receive unemployment benefits for nine weeks longer, and little evidence of health effects for men. We only find a significant improvement in mental health as well as a reduction in injuries in the case of men. We show that these gender differences come from the higher impact of the reform on men as well as their concentration in higher-risk sectors, like construction.

This paper has a limitation that is worth mentioning: our health results rely on ITT estimates as we are unable to identify the labour market status of individuals in the health datasets. This is a limitation compared to other studies which may provide a more precise measure of the effect of unemployment benefits as they can identify which individuals are exactly affected by the policy under analysis (Kuka 2020). However, even if the “treatment” probability (i.e. receiving the LTU benefit) among affected men is relatively low (3.7 pp), we expect them to be overrepresented in the pool of hospitalisations, as they have several socioeconomic and labour market disadvantages (low education, long-term unemployment, and low-occupational jobs, with higher health risks), which are clearly linked to poorer health outcomes (see Tables A15 and A16 in Appendix A).

Finally, we believe that our results are important from a policy perspective as they provide credible evidence on the net health effects of the LTU benefit schemes for disadvantaged workers. We perform a simple back-of-the-envelope calculation to account for the costs of injury hospitalisations that are avoided, and we estimate that those entitled to the benefit incurred in about 1133 fewer injury hospitalisations, which translate into 1,860,000 € yearly hospital expenses (Table A17 in Appendix A). These are significant externalities that should be taken into account when considering the elimination of benefit schemes targeted at disadvantaged middle-aged workers.

Data availability

This paper uses data from the following databases: i) Continuos Sample of Working Lives (“Muestra Continua de Vidas Laborales”, MCVL). MCVL data access is available under request at https://www.seg-social.es/wps/portal/wss/internet/EstadisticasPresupuestosEstudios/Estadisticas/EST211?changeLanguage=es ii) Hospital Morbidity Survey from the Spanish National Institute of Statistics (“Encuesta de morbilidad hospitalaria”, INE). Hospital Morbidity Survey is available under request at https://www.ine.es/dyngs/INEbase/es/operacion.htm?c=Estadistica_C&cid=1254736176778&menu=ultiDatos&idp=1254735573175). iii) “Base de Datos Clinicos de Atencion Primaria, BDCAP” (source: https://www.sanidad.gob.es/estadEstudios/estadisticas/estadisticas/estMinisterio/SIAP/home.htm). Access to BDCAP microdata was granted under a confidential agreement. Further access to BDCAP microdata is currently suspended (as of 09/2023) due to “data protection”. iv) SHARE, the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe. SHARE Waves 5 and 6, were used (DOIs: https://doi.org/10.6103/SHARE.w5.800, https://doi.org/10.6103/SHARE.w6.800). See Börsch-Supan et al. (2013) for methodological details. Data are publicly available for registered users at www.share-project.orgwww.share-project.org.

Notes

Another related paper from Spain (Rebollo-Sanz and Rodríguez-Planas 2020) looked at the labour market effects of a 17% reduction in the amount of UI in 2012. The authors found that this reform, which affected all age cohorts equally, reduced unemployment duration and increased the probability of finding a job.

Following the 2007 Great Recession, two labour market reforms were implemented: one in September, 2010, and another in March, 2012. These reforms aimed at reducing the employment protection gap between permanent and temporary workers by decreasing employment protection levels for permanent contracts, among other measures. However, neither reform affected our “treatment” and “control” groups differently, ensuring that our results are not confounded by them.

The amount of the subsidy is set at 80% of a public income index (IPREM) used as reference by the Spanish Government to determine public subsidies and benefits. In the period under study (2012–2015), this index was set at 532.31€ (source: http://www.iprem.com.es/). The estimated replacement rate of the LTU subsidy with respect to the average salaries in our affected cohort is around 26% for men and 30% for women, although it varies from 22 to 50% depending on the economic sector of activity (Table A1 in Appendix A).

The average expenditure on regional minimum income scheme amounted an average of 0.13% of GDP during the period 1997–2017, as compared to 0.43% of GDP for non-contributory social security unemployment benefits (AIREF 2019). Indeed, the existence of these regional welfare benefits was not enough to compensate the large increase in unemployment following the Great Recession and, as a consequence, the percentage of households with no income increased from 2% in 2007 to 4% in 2012.

See the “Data” section for an explanation of the MCVL dataset.

We use data only up to 2014 precisely because the control group gains access to LTU benefits already by 2015, when they turn 55. This could cause a “catching up” effect in the control group if we were to follow them after 2014, both in labour market and health outcomes. Therefore, the “peak point” in the differential advantage in access to LTU benefit between treatment (1st semester of 1960) and control group (2nd semester of 1960) is 2014, our last year of observation.

Alternatively we might have chosen older cohorts (i.e., born in 1958–1959) instead of the closest younger cohorts (1961–1962). However, individuals in the 1958–1959 cohorts were already eligible for the LTU subsidy before the reform, as they turned 52 prior to 2012 (see Table 1). As a consequence, those born in the 1st semester of 1958–1959 would start receiving the subsidy before those born in the 2nd semester. This could lead to health differences between semesters of birth also within these cohorts and would unable them as a plausible control group. Therefore, the younger cohorts (i.e., 1961–1962), by not having access to the subsidy until 2016, represent a better comparison group as the potential health differences across semesters of birth will be unrelated to the benefit.

Individuals who have exhausted all Social Security benefits can alternatively receive welfare benefits that are managed by the regions. However, the scope of these benefits is limited, as explained in Section 2, and we cannot observe them in our database.

There are 50 provinces in Spain, with a median population of 657,404 inhabitants, as of 2012.

Population data is available from the Spanish National Institute of Statistics per province, cohort of birth, year, and sex but is not available by semester of birth. To approximate it we divide the population of each cohort of birth by two. We then divide the number of hospitalisations by this population in order to get the hospitalisation rate.

Injuries are an indicator of occupational health that can be indirectly affected by the subsidy. LTU subsidy recipients, as explained in Section 2, come from sectors with more physically demanding jobs and are workers with very low educational levels. Therefore, in the absence of the subsidy, these individuals may be forced to accept riskier, unskilled, and manual jobs, since they are left with no alternative source of income. Such jobs are expected to increase the risk of suffering injuries due to work-related accidents (van Ours 2019).

Unfortunately, 2011 was the first year with available data in BDCAP; therefore, we could not test for a longer pre-treatment parallel trend.

Respondents of SHARE must be 50 years or older. The last wave before the reform was carried out in 2011 so that there are no observations for the control cohort (1961–1962), and very few observations for the 1960 cohort.

Those “out of the labour market” were assigned a monthly salary of zero since they are not receiving any formal salary or any Social Security subsidy. However, they could be receiving income from regional welfare benefits that are not included in our dataset. In any case and, as explained in Section 2, the scope of these benefits is quite limited. Additionally, some individuals may be working in the informal sector and receiving some income from this source of illegal employment. Again, this is not registered in our administrative database. Table A7 in Appendix A provides more details on the average monthly salary by employment status as well as on the details of the construction of this variable.

References

Ahammer A, Packham A (2023) Effects of unemployment insurance duration on mental and physical health. J Public Econ 226:104996

AIREF (2019) Los Programas de rentas minimas en España. Retrieved from https://www.airef.es/wp-content/uploads/RENTA_MINIMA/20190626-ESTUDIO-Rentas-minimas.pdf. Accessed 02 Feb 2024

Angrist JD, Keueger AB (1991) Does compulsory school attendance affect schooling and earnings? Q J Econ 106(4):979–1014

Bellés-Obrero C, Jiménez-Martín S, Castello JV (2022) Minimum working age and the gender mortality gap. J Popul Econ 35:1897–1938

Bentolila S, Cahuc P, Dolado JJ, Le Barbanchon T (2012) Two-tier labour markets in the great recession: France Versus Spain. Econ J 122(562):F155–F187

Berck P, Villas-Boas SB (2016) A note on the triple difference in economic models. Appl Econ Lett 23(4):239–242

Browning M, Heinesen E (2012) Effect of job loss due to plant closure on mortality and hospitalization. J Health Econ. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2012.03.001

Buckles KS, Hungerman DM (2013) Season of birth and later outcomes: old questions, new answers. Rev Econ Stat. https://doi.org/10.1162/REST_a_00314

Case A, Deaton A (2017) Mortality and morbidity in the 21st century. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 2017:397

Chetty R (2006) A general formula for the optimal level of social insurance. J Public Econ. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2006.01.004

Costa DL, Lahey JN (2005) Predicting older age mortality trends. J Eur Econ Assoc 3(2–3):487–493

Cygan-Rehm K, Kuehnle D, Oberfichtner M (2017) Bounding the causal effect of unemployment on mental health: nonparametric evidence from four countries. Health Econ 26(12):1844–1861

Cylus J, Glymour MM, Avendano M (2015) Health effects of unemployment benefit program generosity. Am J Public Health. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2014.302253

Domènech-Arumí G, Vannutelli S (2021) Bringing them in or pushing them out? The labor market effects of pro-cyclical unemployment assistance reductions. The Labor Market Effects of Pro-Cyclical Unemployment Assistance Reductions (May 17, 2021)

Farré L, Fasani F, Mueller H (2018) Feeling useless: the effect of unemployment on mental health in the Great Recession. IZA J Labor Econ. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40172-018-0068-5

Gruber JC (1994) The incidence of mandated maternity benefits. Am Econ Rev 84(3):622–641

Hazans M (2011) Informal workers across Europe: evidence from 30 countries. IZA Discussion Papers No 5871. Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA)

Inderbitzin L, Staubli S, Zweimüller J (2016) Extended unemployment benefits and early retirement: program complementarity and program substitution. Am Econ J Econ Pol 8(1):253–288

Kuka E (2020) Quantifying the benefits of social insurance: unemployment insurance and health. Rev Econ Stat 102(3):490–505

Mueller AI, Rothstein J, Von Wachter TM (2016) Unemployment insurance and disability insurance in the Great Recession. J Law Econ 34(S1):S445–S475

Petrongolo B (2009) The long-term effects of job search requirements: evidence from the UK JSA reform. J Public Econ 93(11–12):1234–1253

Rebollo-Sanz YF, Rodríguez-Planas N (2020) When the going gets tough… financial incentives, duration of unemployment, and job-match quality. J Hum Resour 55(1):119–163

Rietveld CA, Webbink D (2016) On the genetic bias of the quarter of birth instrument. Econ Hum Biol 21:137–146

Schaller J, Stevens AH (2015) Short-run effects of job loss on health conditions, health insurance, and health care utilization. J Health Econ. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2015.07.003

Schmieder JF, Von Wachter T (2016) The effects of unemployment insurance benefits: new evidence and interpretation. Ann Rev Econ 8:547–581

SEPE, S. P. E. S (2019) Contributory unemployment benefit. Unemployment protection. Retrieved from https://www.sepe.es/ca/SiteSepe/contenidos/ca/que_es_el_sepe/publicaciones/pdf/pdf_prestaciones/folleto_pres_desemp_ing.pdf. Accessed 02 Feb 2024

Shahidi FV, Muntaner C, Shankardass K, Quiñonez C, Siddiqi A (2020) The effect of welfare reform on the health of the unemployed: evidence from a natural experiment in Germany. J Epidemiol Community Health 74(3):211–218

Staubli S (2011) The impact of stricter criteria for disability insurance on labor force participation. J Public Econ 95(9–10):1223–1235

van Ours JC (2019) Health economics of the workplace: workplace accidents and effects of job loss and retirement. In: Oxford encyclopedia of health economics. Oxford University Press

Acknowledgements

We thank editor Xi Chen, two reviewers, and participants of 6th Irdes-Dauphine Workshop on Applied Health Economics and Policy Evaluation, CRES Seminar, IHEA 2019 conference, EuHEA 2019 PhD conference, and IX Taller Evaluaes. This paper uses data from SHARE Waves 5 and 6 (DOIs: https://doi.org/10.6103/SHARE.w5.710, https://doi.org/10.6103/SHARE.w6.710. We also thank Félix Miguel García for his help with the data from Base de Datos Clínicos de Atención Primaria—BDCAP. The core part of this research project was conducted while MSA was doing a research stay in the CRES, Pompeu Fabra, supported by a PhD Grant (PD/BD/128080/2016) from Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia. Several revisions of the article were conducted while MSA was working at DONDENA Research centre first, and after taking service at the European Commission, Joint Research Centre, later.

Funding

JIGP acknowledges funding from the project ECO2015-65408-R (MINECO/FEDER) and FEDER UPO-1263503. JVC acknowledges funding from the project RTI2018-095983-B-I00 from MCIU/AEI/FEDER, UE.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Responsible editor: Xi Chen

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Garcia-Pérez, J.I., Serrano-Alarcón, M. & Vall-Castelló, J. Long-term unemployment subsidies and middle-aged disadvantaged workers’ health. J Popul Econ 37, 14 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-024-01000-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-024-01000-3