Abstract

We use diary data from representative samples from the USA to examine determinants and historical trends in time-weighted happiness. To do so, we combine fine-grained information on self-reported happiness at the activity level with data on individuals’ time use. We conceptually distinguish time-weighted happiness from evaluative measures of wellbeing and provide evidence of the validity and distinctiveness of this measure. Although time-weighted happiness is largely uncorrelated with economic variables like unemployment and income, it is predictive of several health outcomes and shares many other determinants with evaluative wellbeing. We illustrate the potential use of time-weighted happiness by assessing historical trends in the gender wellbeing gap. For the largest part of the period between 1985 and 2021, women’s time-weighted happiness improved significantly relative to men’s. This is in stark contrast to prominent findings from previous work. However, our recent data from 2021 indicates that about half of women’s gains since the 1980s were lost during the COVID-19 pandemic. Hence, as previously shown for several other outcomes, women appear to have been disproportionally affected by the pandemic. Our results are replicable in UK data and robust to alternative assumptions about respondents’ scale use.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

All datasets used are publicly available.

Notes

Throughout this section, we will take the terms ‘wellbeing’ and ‘utility’, and the terms ‘experienced’ and ‘hedonic’ to be synonymous.

This conclusion depends on assuming both separability (i.e. total utility does not depend on the order in which momentary utilities are experienced) and time-neutrality (i.e. the utility of each moment equally contributes to total experienced utility). Under these assumptions, time-weighed happiness satisfies a principle of temporal monotonicity: adding an extra period of enjoyment to an episode cannot reduce experienced utility of the episode. For a formal derivation see Kahneman et al. (1997).

Hedonic wellbeing is often measured with global single-item measures, too. The question in the General Social Survey, ‘Taken all together, how would you say things are these days--would you say that you are very happy, pretty happy, or not too happy?’, is an example of this. Worries about memory bias would also apply in that case.

Krueger (2007) also found that the percentage of time when the strongest emotion was negative (the so-called U-index) was greater for women than men. Using 2013 ATUS data, we calculate Krueger’s U-index. The index is based on data on four different feelings: happiness, sadness, tiredness, and pain. We estimate that the U-index in 2013 was 0.185 for men and 0.206 for women. This is consistent with Krueger (2007). Therefore, while women appear to experience greater happiness than men, women also experience intense negative emotions more often than men.

Together, all data relating to the USA, apart from the 1985 enjoyment ratings, are sourced from IPUMS. Because the IPUMS version does not contain the enjoyment information in the 1985 AUTP, we incorporate that information directly from the original 1985 data.

As far as we know, the USA and UK are the only two countries where enjoyment or happiness information was collected along with time diaries in both the 1980s and 2010s. The time-use surveys in France and Italy collected enjoyment information in 2010 and 2008, respectively (Cornwell et al. 2019). Since the enjoyment data was collected only once in each country, however, these datasets cannot be used for studying long-term trends.

Since respondents are not asked about a global concept of happiness, as asked in standard surveys, but instead about happiness during a particular activity, we think that this assumption is reasonable. Moreover, using DRM data, Kahneman and Krueger (2006) found that happiness and enjoyment are highly correlated (0.73) within episodes for the same individual.

Sleeping and personal care are excluded when estimating TWH in Eq. (2) because happiness data are not available for these activities in the ATUS data.

The cross-sectional nature of our data does not allow us to give an analysis in which we truly predict health outcomes at time t with time-weighted happiness at t − 1. Unfortunately, no such panel data was available to us. For analyses of this sort in the context of life satisfaction data, see, e.g. Steptoe et al. (2015).

When regressing subjective variables on each other, picking up common-method variance is a concern. However, both objective and subjective variables are all answered on the same binary scale. Hence, any concerns about common-method variance should affect the regressions of subjective and objective outcomes similarly.

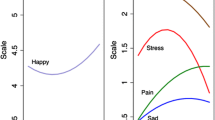

Appendix Figures A3 and A4, respectively, replicate fig. 1 using a more detailed set of 46 activity categories, and using either OLS or an ordered probit model.

Changes in happiness (time-use) between 1985 and 2013 are statistically insignificant for market work, education, and religious activities (shopping, education, and religious activities) for both genders.

One driving mechanism may have been increased loneliness during the pandemic (Lepinteur et al. 2022). Although in our data, men and women experienced a comparable increase in the share of time spent alone during the COVID-19 pandemic (see Appendix Figure A14); women’s TWH is more negatively affected by time spent alone (see the regression coefficients in Appendix Table A4).

Since (0.014 − (−)0.021)/((0.045 − 0.033) + (0.014 − (−)0.021)) = 0.745.

We also decomposed trends in the gender gap into contributions from each individual activity. Appendix Figure A6 shows that the increase in the gender gap between 1985 and 2013 was driven by women allocating more time towards market work, outdoor leisure, and travel, and away from domestic work and indoor leisure. The decline in the gender gap between 2013 and 2021 was mainly driven by reductions in happiness among women during domestic and market work, as well as watching TV and eating meals (see Appendix Figure A7).

The larger increase in the gender gap in the time-weighted happiness in the UK relative to the USA may be explained by differences in trends in time use: We find a larger decline in the gender gap in domestic work time in the UK than the USA between the 1980s and 2010s. However, the USA and UK data differ in terms of sampling and survey design. Therefore, it is hard to be definitive on what drives the difference.

We did so by first dividing the 1985 sample into 32 cells defined by four socio-demographic variables: age (18–29, 30–39, 40–49, 50+), education (H.S. degree or less, some college or above), gender, and marital status (single, married), and subsequently using the shares in each of the 32 cells as reweighting variables.

To identify the model we also assume that τ1985, 8 = τt ≥ 2010, 5 = 0. Setting response thresholds to zero is arbitrary; any other value would have served equally well and would only have shifted the estimated intercept. The more positive overall trend in Fig. 5 is driven by our assumption that the 8th threshold on the 1985 scale has the same location as the 5th threshold on the 2010s scale. If we had made the (implausible) assumption that, say, the 2nd threshold on the 1985 scale was equivalent to the 8th threshold of the 2010s scale, we would have observed an overall negative trend in time-weighted happiness. Importantly, however, the differences in trends between men and women are not driven by this normalization.

We also reproduced Fig. 3 using a 3-point and a 5-point collapse, again yielding the same qualitative results (see Appendix Figures A12 and A13).

References

Adams-Prassl A, Boneva T, Golin M, Rauh C (2022) The impact of the coronavirus lockdown on mental health: evidence from the United States. Econ Policy 37(109):139–155

Adler MD (2019) Measuring social welfare: an introduction. Oxford University Press, Measuring social welfare

Aguiar M, Hurst E (2007) Measuring trends in leisure: the allocation of time over five decades. Q J Econ 122(3):969–1006

Aguiar M, Hurst E, Karabarbounis L (2013) Time use during the great recession. Am Econ Rev 103(5):1664–1696

Anusic I, Lucas RE, Brent Donnellan M (2017) The validity of the day reconstruction method in the german socio-economic panel study. Soc Indic Res 130(1):213–232

Banks J, Xiaowei X (2020) The mental health effects of the first two months of lockdown during the COVID-19 pandemic in the UK. Fisc Stud 41(3):685–708

Bauman A, Bittman M, Gershuny J (2019) A short history of time use research; implications for public health. BMC Public Health 19(Suppl 2):607

Bavel V, Jan CR, Schwartz, and Albert Esteve. (2018) The reversal of the gender gap in education and its consequences for family life. Annu Rev Sociol 44:341–360

Becker GS (1965) A theory of the allocation of time. Econ J 75(299):493–517

Benjamin DJ, Heffetz O, Kimball MS, Szembrot N (2014) Beyond happiness and satisfaction: toward well-being indices based on stated preference. Am Econ Rev 104(9):2698–2735

Bertrand M (2020) Gender in the twenty-first century. In: AEA papers and proceedings, vol 110. American Economic Association, pp 1–24

Blanchflower DG (2021) Is happiness u-shaped everywhere? Age and subjective well-being in 145 countries. J Popul Econ 34(2):575–624

Blanchflower DG, Oswald AJ (2004) Well-being over time in Britain and the USA. J Public Econ 88(7–8):1359–1386

Blau FD, Kahn LM (2017) The gender wage gap: extent, trends, and explanations. J Econ Lit 55(3):789–865

Blinder AS (1973) Wage discrimination: reduced form and structural estimates. J Hum Resour 8(4):436–455. https://doi.org/10.2307/144855

Clark AE (2018) Four decades of the economics of happiness: Where next? Rev Income Wealth 64(2):245–269

Clark E, Senik C (2011) Is happiness different from flourishing? Cross-country evidence from the ESS. Revue d’économie politique 121(1):17–34

Cornwell B, Gershuny J, Sullivan O (2019) The social structure of time: emerging trends and new directions. Annu Rev Sociol 45(1):301–320

Cox NJ (2016) MIPOLATE: Stata module to interpolate values. In: Statistical software components S458070. Boston College Department of Economics

Crisp R (2021) ‘Well-Being’. In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, edited by Edward N. Zalta, Winter 2021. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2021/entries/well-being/. Accessed June 2022

Deci EL, Ryan RM (2008) Hedonia, Eudaimonia, and well-being: an introduction. J Happiness Stud 9(1):1–11

Diamond P (2008) Behavioral economics. J Public Econ 92(8–9):1858–1862

Diener E, Inglehart R, Tay L (2013) Theory and validity of life satisfaction scales. Soc Indic Res 112(3):497–527

Diener E, Tay L (2014) Review of the day reconstruction method (DRM). Soc Indic Res 116(1):255–267

Dockray S, Grant N, Stone AA, Kahneman D, Wardle J, Steptoe A (2010) A comparison of affect ratings obtained with ecological momentary assessment and the day reconstruction method. Soc Indic Res 99(2):269–283

Etheridge B, Spantig L (2022) The gender gap in mental well-being at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic: evidence from the UK. Eur Econ Rev 145(June):104114

Fisher K, Gershuny J, Flood SM, Roman JG, Hofferth SL (2018) American heritage time use study extract builder: version 1.2. IPUMS, Minneapolis. https://doi.org/10.18128/D061.V1.2 Accessed 15 Jan 2024

Flood S, Sayer LC, Backman D (2022) American time use survey data extract builder: version 3.1 [American Time Use Survey 2003-2021]

Frey BS, Benesch C, Stutzer A (2007) Does watching TV make us happy? J Econ Psychol 28(3):283–313

Fumagalli E, Fumagalli L (2022) Subjective well-being and the gender composition of the reference group: evidence from a survey experiment. J Econ Behav Organ 194:196–219

Gershuny J, Sullivan O, Sevilla A, Vega-Rapun M, Foliano F, Lamote J, de Grignon T, Harms, and Pierre Walthery. (2021) A new perspective from time use research on the effects of social restrictions on COVID-19 behavioral infection risk. PloS One 16(2):e0245551

Gimenez-Nadal JI, Sevilla A (2012) Trends in time allocation: a cross-country analysis. Eur Econ Rev 56(6):1338–1359

Goldin C, Katz LF, Kuziemko I (2006) The homecoming of American college women: the reversal of the college gender gap. J Econ Perspect 20(4):133–156

Graham C, Chattopadhyay S (2013) Gender and well-being around the world. Int J Happiness Dev 1(2):212

Han W, Feng X, Zhang M, Peng K, Zhang D (2019) Mood states and everyday creativity: Employing an experience sampling method and a day reconstruction method. Front Psychol 10:1698

Hektner JM, Schmidt JA, Csikszentmihalyi M (2007) Experience sampling method: measuring the quality of everyday life. Sage

Hoang TTA, Knabe A (2021) Replication: Emotional well-being and unemployment–Evidence from the American time-use survey. J Econ Psychol 83:102363

Hurst E (2009) Thoughts on “National Time Accounting: The Currency of Life”. In: Measuring the subjective well-being of nations: national accounts of time use and well-being. University of Chicago Press, pp 227–241

Inglehart RF (2008) Changing values among western publics from 1970 to 2006. West Eur Polit 31(1–2):130–146

Kahneman D (2011) Thinking, fast and slow. Macmillan

Kahneman D, Krueger AB (2006) Developments in the measurement of subjective well-being. J Econ Perspect 20(1):3–24

Kahneman D, Krueger AB, Schkade DA, Schwarz N, Stone AA (2004) A survey method for characterizing daily life experience: the day reconstruction method. Science 306(5702):1776–1780

Kahneman D, Riis J (2005) Living, and thinking about it: two perspectives on life. In: Huppert FA, Baylis N, Keverne B (eds) The science of well-being. Oxford University Press, pp 285–304. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198567523.003.0011. Accessed 15 Jan 2024

Kahneman D, Schkade DA, Fischler C, Krueger AB, Krilla A (2010) ‘The structure of well-being in two cities: life satisfaction and experienced happiness in Columbus, Ohio; and Rennes, France’ International Differences in Well-Being, 16–33

Kahneman D, Wakker PP, Sarin R (1997) Back to Bentham? Explorations of experienced utility. Q J Econ 112(2):375–406

Kaplan G, Schulhofer-Wohl S (2018) The changing (dis-)utility of work. J Econ Perspect 32(3):239–258

Killgore WDS, Cloonan SA, Taylor EC, Dailey NS (2020) Loneliness: a signature mental health concern in the era of COVID-19. Psychiatry Res 290(August):113117

Killingsworth MA (2021) Experienced well-being rises with income, even above $75,000 per year. Proc Natl Acad Sci 118(4):e2016976118

Kitagawa EM (1955) Components of a difference between two rates. J Am Stat Assoc 50(272):1168–1194

Knabe A, Raetzel S, Schoeb R, Joachim W (2010) Dissatisfied with life but having a good day: time-use and well-being of the unemployed. Econ J 120(547):867–889

Krueger AB (2007) Are we having more fun yet? Categorizing and evaluating changes in time allocation. Brook Pap Econ Act 2007(2):193–215

Krueger AB, Kahneman D, Schkade D, Schwarz N, Stone AA (2009) National time accounting: the currency of life. In: Measuring the subjective well-being of nations: national accounts of time use and well-being. University of Chicago Press, pp 9–86

Krueger AB, Mueller AI (2012) Time use, emotional well-being, and unemployment: evidence from longitudinal data. Am Econ Rev 102(3):594–599

Kushlev K, Dunn EW, Lucas RE (2015) Higher income is associated with less daily sadness but not more daily happiness. Soc Psychol Personal Sci 6(5):483–489

Lamote de Grignon Perez, J, M. Vega-Rapun, J. Gershuny, and O. Sullivan (2022) ‘Centre for time use research UK time use survey. 6-Wave Sequence across the COVID-19 Pandemic, 2016-2021’

Lepinteur A, Clark AE, Ferrer-i-Carbonell A, Piper A, Schröder C, D’Ambrosio C (2022) Gender, loneliness and happiness during COVID-19. J Behav Exp Econ 101:101952

Lucas RE, Wallsworth C, Anusic I, Brent Donnellan M (2021) A direct comparison of the day reconstruction method (DRM) and the experience sampling method (ESM). J Pers Soc Psychol 120:816–835

MacKerron G, Powdthavee N (2022) Predicting emotional volatility using 41,000 participants in the United Kingdom. arXiv preprint arXiv:2205.07742

Meisenberg G, Woodley MA (2015) Gender differences in subjective well-being and their relationships with gender equality. J Happiness Stud 16(6):1539–1555

Montgomery M (2022) Reversing the gender gap in happiness. J Econ Behav Organ 196:65–78

Nikolova M, Graham C (2021) The economics of happiness. In: Zimmermann KF (ed) Handbook of labor, human resources and population economics. Springer International Publishing, Cham, pp 1–33. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-57365-6_177-2

Oaxaca R (1973) Male-female wage differentials in urban labor markets. Int Econ Rev 14(3):693–709

OECD (2013) OECD guidelines on measuring subjective well-being. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264191655-en

ONS (2021) ‘Well-being-office for national statistics’. 2021. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/wellbeing. Accessed June 2022

Plant M (2020) Life satisfaction and its discontents. Happier Lives Institute Working Paper https://www.happierlivesinstitute.org/uploads/1/0/9/9/109970865/life_satisfaction_and_its_discontents_jul2020.pdf. Accessed June 2022

Proto E, Quintana-Domeque C (2021) COVID-19 and mental health deterioration by ethnicity and gender in the UK. PloS One 16(1):e0244419

Robinson J, Godbey G (1997) Time for life, vol 56. University Park

Schneiderman N, Ironson G, Siegel SD (2005) Stress and health: psychological, behavioral, and biological determinants. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 1:607–628

Steptoe A, Deaton A, Stone AA (2015) Subjective wellbeing, health, and ageing. Lancet 385(9968):640–648

Stevenson B, Wolfers J (2009) The paradox of declining female happiness. Am Econ J Econ Pol 1(2):190–225

Stiglitz JE, Sen A, Fitoussi JP, and others (2010) Report by the commission on the measurement of economic performance and social progress. Paris: commission on the measurement of economic performance and social progress. http://www.voced.edu.au/content/ngv:44133. Accessed June 2022

Stone AA, Schneider S, Krueger A, Schwartz JE, Deaton A (2018) Experiential wellbeing data from the american time use survey: comparisons with other methods and analytic illustrations with age and income. Soc Indic Res 136(1):359–378

Sullivan O, Gershuny J (2021) ‘United Kingdom Time Use Survey, 2014-2015. SN: 8128’. UK Data Service. https://doi.org/10.5255/UKDA-SN-8128-1

Sumner LW (1996) Welfare, happiness, and ethics. Oxford University Press

Tay L, Ng V, Kuykendall L, Diener E (2014) Demographic factors and worker well-being: an empirical review using representative data from the United States and across the world. In: Perrewé PL, Rosen CC, Halbesleben JRB (eds) Research in Occupational Stress and Well-Being, vol 12. Emerald Group Publishing Limited, pp 235–283

Tiberius V (2015) Prudential value. The Oxford handbook of value theory. Oxford University Press, pp 158–174

Wilson TD, Gilbert DT (2003) Affective forecasting. Adv Exp Soc Psychol 35:345–411

Zamarro G, Prados MJ (2021) Gender differences in couples’ division of childcare, work and mental health during COVID-19. Rev Econ Househ 19(1):11–40

Acknowledgements

We thank editor Klaus F. Zimmermann and three anonymous referees for their suggestions and guidance. We also thank Jan-Emmanuel De Neve, Carol Graham, Daniel Hamermesh, Mark Fabian, Lucia Macchia, Joel McGuire, Alberto Prati, Wei Qian, and Julia Schmidtke, as well as seminar participants at Zhejiang University, the Chinese Economists Society 2021 conference, the ISQOLS 2021 annual conference, and the ASSA 2022 annual conference for their helpful comments. We also thank Jonathan Gershuny for providing the 1985 US and 1986 UK time use data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Responsible editor: Klaus F. Zimmermann

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

ESM 1

(PDF 960 kb)

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Han, J., Kaiser, C. Time use and happiness: US evidence across three decades. J Popul Econ 37, 15 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-024-00982-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-024-00982-4