Abstract

We analyze possible links between both trust and trustworthiness among Syrian refugees in Germany in relation to two different forms of social networking: bonding networks, which include only other Syrians, and bridging networks, which include people from the host country. Our results show that Syrians who engage in bonding networks show higher levels of trust and (un)conditional trustworthiness when interacting with a Syrian compared to a German participant. In turn, for refugees engaged in bridging networks, the positive discrimination refugees display towards their own peers decreases regarding trust and conditional trustworthiness and vanishes regarding unconditional trustworthiness. Newly arrived Syrian refugees tend to engage in bonding networks, whereas the length of stay and having a private home coincide with more bridging networks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Tell me whom you associate with, and I will tell you who you are.

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

1 Introduction

In 2022, Europe faced yet another huge influx of refugees, this time from Ukraine. Their integration into the societies of the new host nations is yet again a major challenge for the European countries (e.g., Hannafi and Marouani 2022; Brell et al. 2020; Edin et al. 2004). For decades, many European countries have witnessed the negative consequences of ethnic segregation and ghettoization for both migrants and members of the hosting society (see, e.g., Simpson 2004, for some evidence from the UK in the 1990s, and Wacquant 1993, from France in the 1980s). Another failure to integrate the current — and possible future — migration waves into their host societies is likely to create substantial disadvantages for all involved parties. Therefore, it seems important to explicitly take the lessons of past refugee waves into account. In our study, we attempt to capitalize on the experience from the Syrian refugee wave during the second half of the previous decade.

Evidence from previous migration waves shows that different socialization patterns are expected to have different consequences for integration: if migrants — be they voluntary (migrants seeking better economic living conditions, for instance by leaving the former Soviet Union in the early 1990s) or forced (i.e., refugees saving their lives outside their home countries, for instance by leaving Syria in the wake of the civil war) — socialize almost exclusively with others who speak the same language or originate from the same cultural background, segregation and parallel societies are likely to emerge (e.g., Andersen 2002; Bolt et al. 2010; Bisin & Verdier 2011). This may happen if they do not socialize with the members of the local population. Consequently, the composition of migrants’ social networks is of pivotal importance: people’s behavior will reflect the type of social networks that they belong to. As Scott (1988) nicely summarizes, the metaphorical use of “social networks” was made popular in classical German sociology — by Weber, Tönnies, and Simmel — in order to describe social relations as a web of interpersonal connections that binds individuals together and has unintended consequences on individuals’ actions. Social networks foster trust (i.e., the willingness of one party to be vulnerable to another party) and trustworthiness (i.e., the willingness of one party not to abuse the vulnerability of another party) between individuals and facilitate the exchange of resources within groups (Coleman 1988),Footnote 1 but they may also create distrust between groups. Therefore, it seems crucial to analyze refugees’ social networks along with their accompanying trust and trustworthiness levels towards Germans. This will allow us to answer our research question whether the type of social network influences the degree of integration — as measured by trust and trustworthiness towards strangers — for forced migrants. For comparison, we analyze the decisions of Germans who face the same set of choices, relating their behavior to the perception of the arrival of refugees in their society.

Social networks have been identified as a key element in understanding how newcomers — such as refugees — adapt to the conventions of a host country (Ryan et al. 2008; Allen 2010; Elliott and Yusuf 2014). Members of social networks may provide each other accommodation, job information, information on social services, and emotional support — all things particularly valuable to recently arrived individuals (Boyd 1989). Social networks that refugees join in the host country are likely to be important in facilitating their adaptation to the new socioeconomic environment. Such networks may arise exclusively among refugees, which we refer to as bonding social networks. They may also include both hosts and refugees; in that case, we refer to them as bridging social networks. The distinction between bonding and bridging networks builds on the influential work of Granovetter (1973).Footnote 2 Putnam (2000) expands on the difference between bonding and bridging social networks. Broadly defined, bonding networks refer to within-group connections, and bridging networks denote connections between groups. Bonding social networks may create in-group favoritism and they may also, as the other side of the coin, create out-group antagonism, although this need not be the case (Putnam 2000). Additionally, bridging social networks may bridge divisions among different ethnic communities (ibid.). Exploring the potential links between involvement in the different types of social networks and individual behavior is the main motivation for this study.

In this study, we ask how the way in which Syrian refugees participate in social networks in their new environment correlates with different levels of trust and trustworthiness. To answer this question, we conduct a one-shot trust game with Syrian and German participants. In this game, the level of trust is measured by the amount of points sent by the first player (trustor) and the level of trustworthiness is measured by the amount of points returned by the second player (trustee). Since the points are tripled on their way to the trustee, the second player can decide whether or not to share the surplus. All participants play both roles once. Trustworthiness is measured using the strategy method as this allows us to collect information on all possible outcomes.Footnote 3 The structure of our experiment enables us to implement randomly applied treatments. That is, we can learn whether the identity of the interacting partner matters: we randomly apply two treatments, a Syrian participant playing with another Syrian participant and a Syrian participant playing with a German participant (and the same for the German participants).Footnote 4

Our study contributes to the recent literature on the behavioral effects of migration — whether voluntary of forced — on both the releasing and the receiving country.Footnote 5 Khadjavi and Tjaden (2018) as well as Cettolin and Suetens (2019) analyze the behavior of participants from the hosting nation towards migrants. Their findings show that the participants from the hosting nation negatively discriminate against migrants from another country. Khadjavi and Tjaden find that new arrivals to a public good setting are required to contribute over-proportionally for the benefit of the incumbent population. Cettolin and Suetens demonstrate that Dutch participants are significantly less trustworthy towards refugees than towards other Dutch participants. Unlike Dutch trustors, refugee trustors on average suffer a loss in terms of payoff when playing the trust game with a Dutch trustee.Footnote 6

A study by Barr and Serra (2010) analyses to which degree migrants transfer behavioral norms from their home societies — particularly, the acceptance of corruption — to decisions made in their new habitat. The authors show that migrants are more likely to accept corruption if it is a generally accepted practice in their home country. Yet the effect decreases significantly with the length of time the migrants have spent in the UK.

We add to the extant literature by analyzing potential transmission mechanisms between the specific form of a social network and individual behavior. That is, we test whether Syrian refugees who form social ties with others of the same or similar nationalities show different forms of trust and trustworthiness than those refugees who hold ties primarily with members of the hosting nation. In a second step, we explore whether refugees form predominantly bonding or bridging ties based on specific aspects of their living conditions in Germany (in particular).

Our results show that the decisions Syrian refugees make in trust games are influenced by the type of social networks they are involved in. Overall, involvement in bonding networks among Syrians positively correlates with more trust, and higher levels of both unconditional (i.e., the amount of money returned by the trustee is independent of how much the other player trusts in the first place) and conditional trustworthiness (i.e., the amount of money returned dependent on how much the other player sends — “trusts” — in the first place) between the members, compared to involvement in bridging networks. However, this effect is almost exclusively caused by the fact that Syrians engaging in bonding networks discriminate positively against other Syrians. That is, they show higher levels of trust and conditional trustworthiness towards potential members of the bonding network than when interacting with members of the hosting nation. This effect is significantly smaller with refugees engaged in bridging networks, and with those refugees who are involved in both bonding and bridging networks. Regarding unconditional trustworthiness, there is no treatment effect. These results suggest that there is a link between co-ethnic solidarity and bonding networks that exists in early stages of the stay in the new environment: newly arrived Syrian refugees tend to engage in bonding — strengthening co-ethnic ties, whereas those having stayed longer in Germany tend to engage more in bridging. Moreover, residence in private houses is significantly correlated with bridging activities of refugees, while residence in refugee camps is not. Therefore, staying in a camp seems to be a key barrier for the proliferation of social networks between hosts and refugees, and a crucial factor hampering integration efforts into the German society. We do not find a significant difference in the trust behavior among Germans depending on whether they interact with one another or with Syrian refugees.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows: In the next section, we present the hypotheses we propose to test. Section 3 describes the game. Section 4 explains how the refugees were recruited and the experiments conducted. Section 5 discusses the results of our experiment. Section 6 shares our conclusions.

2 Framework and hypotheses

Negative consequences such as sectarianism, ethnocentrism, and corruption, as well as positive consequences such as cooperation, trust, and mutual support, are two sides of social networks (Putnam 2000). Taking the ambivalent effects of social networks into account, scholars have proposed to distinguish two types of social networks (Putnam 2000; Paxton 2002): bonding social networks — exclusive networks that tend to reinforce homogeneous groups — and bridging social networks — inclusive networks that tend to include people from diverse social backgrounds (Putnam 2000). We utilize the contrasts between bonding and bridging networks to examine possible links to individual behaviors in different treatment scenarios among Syrian refugees in Germany.

Bonding networks have been characterized as a source of context-specific reciprocity and solidarity (Putnam 2000). Migrants’ social networks have been frequently considered to be based on co-ethnic solidarity (Portes and Sensenbrenner 1993; Sanders and Nee 1996), and on high levels of trust that may increase the likelihood of exchange of resources (Coleman 1988). We expect to find a link between refugees who engage in bonding networks and a positive discrimination towards fellow refugees, in terms of high levels of trust and trustworthiness between refugees. Social networks that bond refugees together can become a safety net for potentially traumatized refugees upon arrival, which can help facilitate resilience in the host country (Hurlbert et al. 2000). Moreover, valuable information about socio-cultural norms in the host country is likely shared through social networks among refugees. Being actively engaged in these social networks can help newly arrived refugees to adapt to the new environment. However, bonding networks may also have negative external effects for society, as it can exclude other individuals with different backgrounds from the expected returns (Staveren and Knorringa 2007). Overall, it seems that refugees engaging in bonding networks positively discriminate against trustors from the same nationality. This implies

-

H1: Refugee participants who engage in bonding networks show higher levels of trust and unconditional trustworthiness when playing with potential members of the bonding network than when playing with others.

On the other hand, bridging networks can foster broader identities and general reciprocation (Putnam 2000). Bridging networks arise out of volunteer interactions between individuals with different backgrounds. ReciprocityFootnote 7 is a fundamental element for this way of networking, which can support collective action benefiting more members from all walks of society (Larsen et al. 2004). Inter-ethnic networks can be valuable to immigrants in many ways. Information related to the bureaucratic asylum process shared between hosts and refugees can be helpful for refugees. Additionally, having a wider social network with a high number of acquaintances facilitates immigrant participation in the host society and can be central to them accessing the labor market, as most employers are nationals (Heath and Yu 2005). Bridging networks can thus be a key element for integrating refugees into their host country. Bridging networks tend to rely to a much larger degree on mutual reciprocation, as its members have little in common per se. Therefore, we expect to find a strong link between engaging in bridging networks and conditional trustworthiness between refugees and hosts, hypothesizing that:

-

H2: Bridging networks are associated with higher levels of conditional (i.e., reciprocal) trustworthiness compared to bonding networks.

There is some ambiguity regarding the classification of bonding and bridging networks as social networks can have characteristics of both bonding and bridging simultaneously. Groups that share a similar background are not completely similar in every aspect, and may create bonding networks, as group members may belong to different generations, different genders, or have different levels of education. Conversely, groups that engage in bridging networks may involve individuals with the same age, gender, or level of education. In order to reduce the ambiguity of our categorization, we will always control for a number of background variables in our analysis.

To classify social networks into bonding and bridging ones, we follow previous research that focuses on co-ethnic and co-religious characteristics for the dichotomous categorization. Religious associations are predominantly conceived as having characteristics of bonding networks when they are part of a religious minority (Paxton 2002; Menahem et al. 2011); otherwise, religious centers have also been categorized as a means of building bridging relationships (Strang and Quinn 2021). Being part of a minority religion is usually associated with bonding social networks (Allen 2010). They can reaffirm ethnic identities and facilitate the practice of familiar religious rituals in a new environment (Hirschman 2004).Footnote 8 In this study, we operationalize mosque attendance as a measure for involvement in bonding social networks following previous research. This variable is coded as a dummy taking the value 1 if participants state that they attend the mosque and 0 otherwise. This is also justified because Islam is a minority religion in Germany. In contrast, we ask how participants take part in the new society, for instance by means of sports or environmental associations. These are categorized as networks that connect individuals who belong to different groups — that is, as bridging networks (Paxton 2002; Stolle and Rochon 1998; Coffé and Geys 2007). Accordingly, we include the following types of social networks to the category of bridging networks: youth clubs, sports clubs, student activities, neighborhood associations, and volunteer work. This variable is also coded as a dummy and takes the value of 1 if participants engage in at least one kind of these bridging social networks and 0 otherwise.Footnote 9

It is unlikely that trust and trustworthiness are completely determined by membership in either of the two types of social networks relied upon here. This is why we always control for a number of potential confounders. We control for length of residence as with a longer stay in Germany, refugees may have become more acquainted with the local mores and feel less uncertain which may be associated with higher levels of both trust and trustworthiness. We measure bonding ties solely based on mosque attendance. Although this is established practice in the literature, mosque attendance may be an indicator of religiosity, rather than part and parcel of a bonding network.Footnote 10 To control for that possibility, we always included a measure of religiosity as elicited in the post-experimental survey.

Social ties can also be influenced by employment and education (Marmaros and Sacerdote 2002; Behtoui 2016; Lépine and Estevan 2021), since, in our case, they may predict permanency in Germany and hence affect the willingness to interact with Germans. However, including employment status makes little sense as in Germany, refugees are only allowed to take up an employment after a number of steps (such as having completed language and cultural lessons and, most importantly, after having been recognized as a refugee and given a permit to stay). Education and employment status are often closely linked. Here, we include education because it may be associated with a higher willingness to make an effort to get to know others (Alesina and Ferrara 2002), as well as forecasting economic success (Hartog and Zorlu 2009). In addition, we control for a number of standard socio-demographic controls such as age, gender, and being married.

3 The game

We use a version of the trust game that is very similar to that originally proposed by Berg et al. (1995) to measure participants’ trust and trustworthiness. There are two players, a trustor and a trustee, both receiving an identical initial endowment of 150 points. The trustor can send any amount of points to the trustee between 0 and 150 points, in multiples of 50 points. On its way to the trustee, the amount is tripled. This means that the trustee has a total of 150, 300, 450, or 600 points. The trustee then decides how many points to keep and how many to send back — if any. Participants complete the game in both roles, trustor and trustee. Importantly, the trustee’s decision is collected implementing the strategy method, revealing the number of points that the trustee would send back if the trustor sent 0, 50, 100, or 150 points to the trustee. The payment is then made between a randomly formed pair of players, one in the role of the trustor, the other in the role of the trustee. Payoffs were determined by matching the trustor’s decision with the corresponding decision from the trustee’s set of decisions.Footnote 11

Conventional economic rationale predicts that no points will ever be sent, because the trustee is expected to keep all the points (s)he has received. That is anticipated by the trustor who, in turn, does not send any points. Amounts sent by the trustor are referred to as trust in the literature, whereas amounts sent back by the trustee are interpreted as trustworthiness. To learn whether the identity of the interacting partner matters for both trust and trustworthiness, we apply two treatment conditions: a Syrian participant playing against another Syrian participant and a Syrian participant playing the game against a German participant.Footnote 12

Notice that relying on the strategy method allows us to distinguish two motives as to why trustees return points to the trustor. On the one hand, the trustee could be generally altruistic towards the trustor (perhaps the trustee is, for instance, altruistic and tries to increase the endowment of the trustor by sending the money). We refer to this case as unconditional trustworthiness, as the trustee will return some points irrespective of whether the trustor sent any points in the first place. On the other hand, the trustee may return points because he or she desires to reciprocate the trust of the trustor. We will denote this case as conditional trustworthiness: the trustee reciprocates the behavior of the trustor; in other words, the more points the trustor has sent, the more points the trustee will return.

The structure of the game gives us five observations per participant. Every participant plays first the role of the trustor and then the role of the trustee. Consequently, we have one observation per participant in the role of the trustor and, applying the strategy method, four in the role of the trustee (one on how many points to return for each possible amount sent by the trustor). That is, the trustee decides how many points to return if the trustor sent 0 points, 50 points, 100 points, and 150 points, not knowing which of the four decisions may become payoff relevant subsequently, and irrespective of the amount the participant sent herself in the role of the trustor.

This enables us to separate unconditional from conditional trustworthiness. Eliciting four responses by trustees trades off time restrictions (with too many questions risking to lose participants’ attention) with a sufficient number of observations to estimate both an intercept and a slope for trustees’ response. To do so, we compute an individual ordinary least square estimation for each participant, with the four amounts sent back from the strategy method as dependent variables, and the four potential amounts sent by the trustor as independent variables. This procedure allows us to estimate a function consisting of an intercept and a slope of the amount sent. We interpret the slope as conditional trustworthiness (i.e., the share of a point of trust that is returned), while the intercept as our measure for the unconditional trustworthiness (i.e., the number of points that are transferred independently of the behavior of the interaction partner).

4 Experimental procedure

The experiment underlying this study was conducted as a lab-in-the-field experiment between January 2017 and July 2018 in Germany.Footnote 13The authors have used a similar approach elsewhere to analyze, among other things, the specific behavior of Syrian refugees in Jordan (El-Bialy et al. 2022).

Today, most experimental economists rely on established laboratory structures for recruiting their participants. For a variety of reasons, those methods do not work for recruiting Syrian refugees. We have tried our best to replicate the volunteer recruitment process usually carried out with students at university campuses, in which recruiters hand out invitations for an academic study. Syrian participants were recruited via Syrian student assistants from a variety of different setups including, refugee camps, refugee-student groups via a social network, language and culture courses, former Syrian employers, and from Syrian restaurants. A brief explanation of the study was distributed either electronically or in form of a flyer. Syrian refugees who were interested in participating were asked to register online via a registration form; alternatively, they could join our social network group or just come by to the experimental session on site. Information regarding the purpose of the study, participants’ rights and anonymity during the experiment, and the confidentiality of their data was provided in written form to participants at the beginning of each session. Descriptive statistics regarding the refugee sample are contained in Appendix Table 1. The average Syrian participant in this study is between 26 and 37 years old, has at least a high school degree, is male and single, has stayed on average 24 months in Germany, is Muslim (only 4 participants claim to be Christians), and religion is somewhat important in his life. German participants were invited to participate relying on the subject pool of a university’s experimental laboratory that includes both students and non-student citizens living in Hamburg (Bock et al. 2014).Footnote 14 Descriptive statistics regarding the hosting society sample are contained in Appendix Table 2.

The instructions of the game were formulated in Arabic and written in a neutral way (see the Appendix A4 for the English version).Footnote 15 Semantic equivalence was ensured by having a group of native speakers translate the English version into Arabic, then having a second group translate it back into English. Anonymity was guaranteed throughout the sessions, and it was made clear that participants could exit the study at any time and that the post-experimental questionnaire was not compulsory.

The experiment was followed by a post-experiment questionnaire with basic socio-demographic questions including age and gender, as well as questions related to participation in social activities in the host society. There were also questions related to post-traumatic-stress-disorder (PTSD) symptoms that people may experience after going through hurtful or terrifying events, which we denote here as “distress level.” In the distress part of the questionnaire, participants could rate potential feelings of unease (e.g., “unable to feel emotions”) on a four-point scale ranging from “not at all” to “a little” to “quite a bit” to “extremely.”Footnote 16

The experiments were run in three different German cities — Hamburg, Stuttgart, and Leipzig.Footnote 17 During the experiment, questions raised by the participants were answered in private. Every participant was assigned a different personal code used for claiming their payments. Points earned during the experiment were converted to Euros at a rate of 1 point to 1 Eurocent. The average duration of the trust game part of the experiment took about 10 min (a complete session lasted about 90 min), and average earnings in the trust game were 2 Euros (participants earned additional money in other parts of the experiment). At the end, these were handed out in sealed envelopes, and the specific amount received was kept confidential.

5 Results

As mentioned earlier, we implement a between-subjects treatment condition in which a Syrian participant either interacts with another Syrian participant (N = 82), or a German participant (N = 70). Figure 1 shows trust results divided by our treatment condition. On average, Syrian trustors sent 45.7 points to a German trustee, compared with 52.4 points sent to a Syrian trustee. This difference in trust between treatment conditions is statistically insignificant (Wilcoxon rank sum test, p-value = 0.5937).

Figures 2 and 3 show the second variable of the game, trustworthiness, measured by the values for the individual intercepts and slopes (i.e., the unconditional trustworthiness and the conditional trustworthiness, respectively) estimated in our regression analysis mentioned earlier. Figure 2 shows the average intercept (i.e., the amount the trustee sends on average independent of the amount received by the trustor). Syrians show on average an unconditional return of 32.9 points to a German trustor, while they return 54.4 points to a Syrian trustor. This difference proves to be statistically significant (Wilcoxon rank sum test, p-value = 0.0146).

Figure 3 illustrates the average slope (i.e., the share of a point of trust that is returned conditionally on the behavior of the trustor). The slope estimate for Syrian participants who interact with a German participant in the game yields 0.999 on average, which is very close to 1, meaning participants will be returning the same amount of points that they received. This is a minor form of cooperation, since trustees keep all the surplus for themselves. Syrian trustees who play with another Syrian participant send back on average 1.36 of the amount of points received, meaning they are sending back some of the amount tripled by the experimenter. This treatment difference is also statistically significant (Wilcoxon rank sum test, p-value = 0.0441).

These results show that Syrians interacting with other Syrians display higher levels of both conditional and unconditional trustworthiness than when interacting with Germans. In the next step of the analysis, we take the heterogeneity in the behavior of the Syrians explicitly into account and ask whether it can be explained by relying on the two different types of social networks introduced above. To do so, we rely on the information revealed by the participants in the post-experimental survey.Footnote 18 Specifically, we elicit whether participants engage solely in bonding or bridging networks, or in both. In our sample, 15% of our participants are solely engaged in bonding networks (hereafter: BonNet), 19% participate in both bonding and bridging networks (hereafter: BBNet), and 66% are engaged exclusively in bridging networks (hereafter: BriNet).

Figure 4 shows the average number of points sent by Syrian trustors. From left to right, we see the different ways in which Syrian participants engage in social networks: either exclusively through bonding, through both bonding and bridging, or through bridging only. Additionally, we add the treatment information of whether participants interacted with a Syrian or a German participant. Our between-subjects experimental design allows us to see whether the identity of the receiver matters for the amount sent by the trustor, taking the different forms of participation in the two types of social networks into account. We find significant differences in trust levels across social networks but not between treatment scenarios within a specific social network.Footnote 19 As shown in Fig. 4, participating in bonding networks correlates with higher levels of trust towards other members of the “bonded” group. Specifically, Syrian participants who engage in bonding networks send more points to another Syrian participant compared to those Syrians who participate in bridging networks when they interact with another Syrian (Wilcoxon rank sum test, p-value = 0.01734).

As mentioned before, to analyze possible links between social networks and trustworthiness, we unbundle the behavior of the trustee into two components, an unconditional and a conditional one. Figure 5 shows the values for the individual intercepts (i.e., the unconditional trustworthiness) estimated in our regression analysis. Syrians who engage in bonding networks display substantially higher levels of unconditional trustworthiness towards a fellow Syrian participant than those engaged in bridging networks (90 points versus 49 points). We interpret the high level of unconditional trustworthiness among Syrian participants who bond as co-ethnic solidarity. Treatment effects are visible, but only statistically significant for Syrians in bridging networks.Footnote 20 Syrian participants who engage in bonding networks send on average 90 points unconditionally to another Syrian, while they send on average 70 points unconditionally to a German participant. Meanwhile, Syrians who bridge send unconditionally on average 49 points to fellow Syrian participants, and 29 points to German participants. Here again, across social networks, bonding participants send significantly more points unconditionally than bridging ones (BonNet with Syr and BriNet with Syrian: p-value= 0.009; BonNet with German and BriNet with German: p-value = 0.001).

Figure 6 shows the coefficients for conditional trustworthiness.Footnote 21 There is a significant difference in the way Syrians — who engage only in bonding networks — interact with other Syrians versus Germans, but not for those engaging in both bonding and bridging, or only in bridging social networks.Footnote 22 The difference in the slope estimates for Syrian participants who engage in bonding networks and interact either with a German or a Syrian participant equals 0.928, while the treatment slope difference among those who bridge is 0.194. Although both groups tend to favor fellow Syrians, the treatment effect among those who bond almost amounts to the whole amount of points sent by the trustor, while it decreases to around 20% of the amount sent by the trustor for those who bridge.Footnote 23

For an in-depth analysis of these results, and to empirically test our hypotheses, we estimate regression models on trust and trustworthiness and test whether the social networks Syrian participants engage in affect individual behavior, explicitly controlling for potentially relevant confounders such as age, gender, and education level. The OLS regression model in Table 1 focuses on trust.Footnote 24 The dependent variable is the proportion of points sent by Syrian trustors and, hence, our measure for trust.Footnote 25 The individual characteristics that are controlled for in the regression models are justified by previous evidence that shows how these variables may influence trust, in particular: the lack of income and education can negatively affect trust (Alesina and Ferrara 2002), age is positively correlated with trust (Greiner and Zednik 2019), males haven been found to be more trusting while females are more trustworthy (Buchan et al. 2008), the level of religiosity can both be a potential determinant for trust (Tan and Vogel 2008) but also for distrust between heterogeneous groups (Fershtman et al. 2005), and, finally, unmarried individuals have been found to be less trusting than married ones (Lindström 2012).

In the model (1), bonding networks are the omitted variable (in model (2) bridging networks). The (weakly) significant constant term of 0.586 thus shows that bonding networks are positively correlated with trust among Syrians. The BriNet (BonNet) coefficient of −0.391 (0.391) indicates the significant difference between refugees engaging in bridging and bonding networks, while the interaction terms BriNet * withGerman and BonNet * withGerman test for deviations from the overall trend when interacting with Germans. In other words, among Syrians who interact with another Syrian, those engaged in BriNet send significantly fewer points compared to those engaged in BonNet (technically, the proportion of trust decreases with a p-value < .01).

However, as selection into social networks is endogenous, we now estimate the effect of our randomized treatments within the same social network categorization. The first treatment difference is indicated by the withGerman variable: the coefficient shows the difference between BonNet * withGerman and BonNet in model (2). We find no significant difference, insinuating that the identity of the interaction partner does not matter for the level of trust among Syrians who engage in BonNet. Rather, BonNet is frequently related to high levels of intra-group trust points (0.391 with p-value < 0.01). This result is, hence, in line with our first hypothesis: participants who engage in bonding networks show higher levels of trust. The following interaction terms show that the treatment effect is insignificant for participants who engage in both bridging and bonding and for those who only engage in bridging exclusively, as shown by the coefficients for withGerman * BBNet and withGerman * BriNet in model (1).Footnote 26 The level of religiosity is controlled for and remains insignificant. The remaining potential confounders are also not significantly associated with the number of points sent, except for Syrian males, who sent significantly more points (0.19 with p-value < 0.05).

The OLS regression models in Table 2 analyze trustworthiness. The dependent variable in model (1) is the individual intercept indicating the number of points returned by the trustee, even without receiving points. This kind of unconditional trustworthiness can be interpreted as a proxy for co-ethnic solidarity when it appears within an ethnic group and not — or to a significantly lower extent — between groups. Again, the BriNet coefficient (0.416 with p-value < 0.05) indicates the difference between refugees engaging in bridging and bonding networks (BonNet being again the baseline for the social networks), while the interaction terms BriNet * withGerman and BonNet * withGerman test for deviations from the overall trend when interacting with Germans. Syrians who engage in bonding networks and interact with a fellow Syrian send around 40 points more than those engaged in bridging networks. But again, endogeneity concerns loom large, and we are, hence, particularly interested in the results of the randomized treatments.Footnote 27 The coefficient of the withGerman variable shows the effect of being randomly assigned to a German participant, compared to playing with a fellow Syrian. It is negative but insignificant in regard to unconditional trustworthiness (intercept). In other words, Syrians who bond with fellow Syrians do not send more points back compared to those who interact with a German participant.

The dependent variable in model (2) of Table 2 is a coefficient estimated individually for each participant based on the number of points returned by the trustee that are conditional on the number of points sent by the trustor (i.e., the slope). In general, trust is reciprocated, yet not equally. Results show that there is — analogous to model (1) — a significant difference between BriNet and BonNet: among Syrians who play with a fellow Syrian, bonding network usage is associated with higher amounts of conditional trustworthiness compared to bridging network usage. We therefore cannot corroborate our second hypothesis according to which we expect participants in bridging networks to display higher levels of conditional trustworthiness compared to members of bonding networks. Although bridging networks are based on reciprocity and one could expect to see a link between the reciprocation of trust and bridging networks, the presence of an interacting partner (in this case a fellow Syrian refugee) seems to overrule the link between individual behavior and social networks. Again, we analyze the treatment effect to alleviate endogeneity concerns. There is a negative and significant coefficient for withGerman: Syrians who bond show higher levels of conditional trustworthiness when they play with a Syrian compared to when playing with a German participant (1% level). This effect is significantly reduced for Syrians who engage in bonding and bridging (10% level) and those who exclusively engage in bridging (5% level). Finally, married Syrian participants tend to send a higher amount of points back conditional on the number of points received compared to those who are not married (5% level).

Importantly, Appendix Tables 7–9 show OLS regression analyses on trust and trustworthiness controlling for the length of stay in Germany and the social networks separately as a robustness check. With this, we control for the possibility that the correlation of social ties and trust might only reflect the passage of time in Germany. Appendix Tables 7–9 show that the length of stay in Germany per se does not correlate with our measurement of trust and trustworthiness from the games, meaning that the way our participants engage in the hosting society correlates with trust independently of the length of their stay in Germany.

Finally, we explore the selection into specific networks. To analyze possible determinants of bonding and bridging networks among Syrian refugees, we estimate two separate probit models: model (1) for the bonding network membership and model (2) for the bridging network membership. We report the marginal effects with the same control variables as above. Furthermore, we introduce additional variables measuring the living conditions of participants, including their distress levels as discussed above.Footnote 28 Bonding networks have been characterized as a source of resilience after experiencing a difficult situation. These kinds of networks can help refugees upon arrival to the host country through, for instance, providing comfort and sharing helpful information. Hence, it could be the case that individuals with high distress levels are more likely to participate in bonding networks. In contrast, we measure the living conditions by a dummy variable indicating whether refugees live in private housing. Potentially, private housing may facilitate contact with the hosting population. Often, the neighborhood may be the only chance to meet Germans recurrently. Hence, it could be that refugees with private housing are more likely to participate in bridging networks than refugees who live in reception centers or refugee housing.Footnote 29 Table 3 reports the mean marginal effects.

Model (1) shows that the association between mental distress and the participation in bonding networks is low. Interestingly, the length of residence in Germany is negatively and significantly correlated with BonNet (5% level). That is, Syrian refugees who have recently arrived in Germany primarily engage in bonding networks, while those networks decrease in their importance the longer refugees stay in Germany. This link underlines the fact that bonding networks can provide support for newly arrived refugees regardless of the individual level of distress. Additionally, being married is positively associated with engaging in bonding ties solely. The likelihood of married Syrians to engage in bonding networks is 14 percentage points above those who are not married. There are no other significant associations between socio-demographic variables and the formation of bonding networks.

The coefficients in model (2) indicate a major insight about membership in bridging networks. In contrast to the development of bonding networks, membership in bridging networks is not systematically linked to the length of residence in Germany. However, private housing in Germany is positively associated with the participation in bridging networks.Footnote 30 Private housing provides advantages for both the refugees as well as the (German) hosting population: by searching for and finding a private home to live in, the refugees have taken an important step towards a more self-determined life, which is likely to increase self-esteem and well-being. Living in a private home may also correlate with greater trust in members of the hosting society based on higher incidents of contact and bilateral exchange.Footnote 31 A possible policy implication of these findings would suggest that the hosting society might be well advised to facilitate private housing options, as refugee camps and reception centers coincide with distrust, and foster segregation. Model (2) also shows that refugees displaying a high distress level are less likely to engage in bridging networks. They might lack the initiative and energy necessary to engage in such activities.

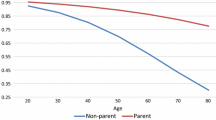

The link between the length of residence in Germany and social networks is nicely depicted in Fig. 7. It shows the average length of residence in Germany for Syrian participants grouped by bonding, bonding and bridging, and bridging. The average length of residence of those engaged in bonding networks is significantly lower than that of Syrian participants who are engaged in bridging networks — 19 months versus 26 months, respectively.Footnote 32 Logically, the development of cross-cutting social networks takes more time than those networks developed within a community.

This is in line with existing research that shows a positive correlation between the length of residence and between-group social networking (Kasarda and Janowitz 1974; Schulz et al. 2006). This result may indicate that the support required by newly arrived refugees differs from the support required after a lengthier stay. However, a longitudinal study would be needed to analyze this conjecture. It could also be that the length of stay in Germany has some important confounders, as it could be a proxy for living conditions: 32% of our Syrian participants were living in a refugee camp in Germany at the time the study was conducted. This variable negatively correlates with the length of residence in Germany (ρ = −.4182, p-value < 0.001).

Upon arrival in Germany, refugees must stay in refugee camps, also called first reception centers. Once they have been granted asylum, they can move out of the reception center, either into refugee housing or private housing. Possibly, living in a refugee camp acts as a sort of natural barrier for social networking with members of the host society.Footnote 33 As mentioned by Burt (1997) and Putnam (2000), this correlation has vital implications for refugees, because refugees might benefit from bridging networks with members of the host society in order to help them adapt to the new socio-cultural environment more quickly.

6 Concluding remarks

In accordance with John Donne’s famous line “no man is an island” (1624), we have determined that refugees’ engagement in social networks is linked to their socio-economic behavior. To demonstrate this, we ran economic experiments with Syrian refugees in Germany, analyzing whether the way in which Syrian refugees participate in the host society is linked to trust and trustworthiness in different treatment scenarios. Among Syrians, the use of bonding networks positively correlates with more trust and unconditional trustworthiness towards one another than does the use of bridging networks. Moreover, regarding the treatment scenarios, Syrian participants who engage in bonding networks show higher levels of trust and conditional trustworthiness towards potential members of the bonding network than they show towards outsiders. Regarding trust, this treatment effect is insignificant for those using only bridging networks or the combination of both types. Regarding conditional trustworthiness, the treatment effect remains significant, yet the difference decreases for those using bridging networks or the combination of both types. Regarding unconditional trustworthiness, there is no treatment effect whatsoever. These results suggest that a link exists between co-ethnic solidarity and bonding networks. On the other hand, our initial analysis of the behavior of the German participants shows that they do not display much of a distinction when they are interacting with either a Syrian refugee or with another German participant.

Immigrant participation in bonding social networks has been shown to have some negative effects for the host society, because at times the bonding networks potentially create parallel societies with segregated business circles, segregated education, and segregated norms. However, our results show that bonding networks can also be crucial for overcoming challenging situations, especially for refugees upon arrival in the host country. For example, moving to a new country often entails a disruption of past social connections (Torres and Casey 2017; Boyle et al. 2008), and establishing a new set of connections can be extremely helpful, even crucial, to immigrants and refugees facing the difficult task of starting a new life in a new and unfamiliar environment.

A refugee’s length of residence and place of residence also play a relevant role in the evolution of their use of social networks. Newly arrived Syrian refugees tend to engage in social activities that strengthen co-ethnic ties, while for those with a longer stay in Germany, and those who reside in private housing in Germany, connections with the host society prevail. Both factors coincide with the formation of bridging ties and the mitigation of discrimination between Syrian and German interaction partners in the experiments. Conversely, residence in a refugee camp seems to act as a barrier to the creation of social networks between hosts and refugees, implying some manifestation of segregation. It is important that the hosting society set institutional conditions in ways that facilitate integration rather than segregation. Acquiring private housing and finding a new job both appear to be significant assets for immigrants along the integration path.

Both bonding and bridging social networking are important tools that can be of great help to immigrants and refugees in their host countries. Bonding can help establish safety nets for the refugees. Bridging, on the other hand, can aid the immigrants in adapting to their new socio-cultural environment and progressing as active members of their new society. It is crucial to note that integration of newly arrived refugees into the society is not solely on their shoulders. Integration is a two-way street. On the one hand, refugee involvement in voluntary social networks is associated with less segregation and less segregation and discrimination (i.e., a decrease of the positive, negative, respectively, discrimination refugees display towards Syrians, Germans, respectively, regarding trust and conditional trustworthiness and the absence of a significant difference in unconditional trustworthiness, as shown in our regression analysis). On the other hand, how Germans accept refugees into those networks is very much determined by whether their efforts are going to succeed or not. Hosting governments should encourage the establishment of bridging networks among the new migrants in their societies and their citizens.

Of course, our results are limited in the sense that they rely partly on endogenous variations. That is, our participants choose their bridging or bounding activities themselves prior to the experiment (while the interaction partner, refugees or Germans, is an exogenous treatment variation). Thus, we offer only correlations, but no causal evidence. In other words, we cannot disentangle whether refugees are per se less trustworthy (i.e., model (1) in Table 2) because they engage in bridging network activities, or whether those refugees engage in bridging activities who are per se less trustworthy. We invite future research to find a way bypassing this crucial limitation of our results and to complement our important insights for the hopefully beneficial interactions between refugees and members of the hosting society.

Data availability

The complete data file as well as the master instructions of the entire experiment are available at the open science framework: https://osf.io/24fbv/.

Notes

Coleman emphasizes the importance of social capital for the formation of human capital. Specifically, he finds a positive correlation between social networks inside and outside the family and remaining in high school until graduation.

Granovetter distinguishes between strong and weak ties. Strong ties exist between members of a group with significant similarities that frequently interact with one another, for instance, family and close friends. Weak ties are characterized by distant social relationships and infrequent interactions; these are usually found between acquaintances.

For the validation of the strategy method in public goods experiments see Fischbacher et al. (2012). Brandts and Charness (2011) nicely summarize the literature regarding whether the strategy method affects participants’ choices compared to a direct-response method and find a majority of papers showing no significant difference. However, some papers do show that when eliciting punishment, participants make lower choices in the strategy method than in a direct-choice mechanism.

An alternative way to elicit the degree to which others are trusted is by way of surveys as, for instance, in the World Values Survey. Experiments have the advantage that people make real decisions regarding trust and trustworthiness that have direct consequences in terms of payoffs. Fehr (2009) compares the pros and cons of eliciting trust levels via surveys as opposed to experiments. He also deals with some of the inconsistencies in the most commonly used survey questions on trust.

In our literature review, we consider both studies analyzing the behavior of, and the behavior towards, voluntary migration and forced migration (i.e., refugees). Quite a number of studies explore specific behavioral anomalies of refugees resulting from the experience of extreme violence, war, and flight (e.g., Bauer et al. 2016, El-Bialy et al. 2022).

However, Jeworrek et al. (2021) find that the willingness to give money to individual refugees increases significantly when those refugees are known to provide volunteer activities for their peers or members of the hosting nation.

Reciprocity can be interpreted as the willingness to be kind or hostile in response to kind or hostile actions (Fehr and Gächter 1998).

However, due to several contextual reasons, religious associations can also have a bridging aspect as they may connect refugees to the wider society. The religious backgrounds of refugees and the level of secularity in society are some important factors determining the bonding or bridging role of religious associations. In Western Europe, religious networks are mainly seen as creating bonding ties, while in the USA, they play rather a bridging role (see Foner and Alba 2008).

The following frequencies are found for each category that composes the bridging social networks: 72% engage in sports clubs, 55% in volunteer work, 36% in youth clubs, 34% in student activities, and 12% in neighborhood associations. Out of those participants who claim to engage in bridging activities, 68 do so in only one activity, 28 in two activities, 11 in three activities, 6 in four activities, and 1 participant in all five bridging activities. It remains an open question whether participants’ extroversion or open-mindedness affects both their willingness to engage in social networks and their behavior. Finally, the quality of social ties also remains unanswered in this study and could be addressed in future research.

Scholars of the sociology of religion have long argued that religion is primarily about the relationship to one’s peers (as put in a nutshell by Isaac B. Singer: “But now at least he understood his religion: its essence was the relation between man and his fellows.”). Moreover, religions are often said to promote in-group morality and out-group hostility. Scholars of social identity theory as, for instance, promoted by Turner et al. (1979), may argue that shared religious beliefs — in particular, if they are only shared by a minority — are conducive to membership in bonding networks.

The average payoff from the trust game was of around 2 EUR. The total payoff for participating in the study comprehended all payoffs of the other games implemented in the study.

One may argue in favor of another “neutral” treatment condition without any information about the identity of the interaction partner. Not providing this information, however, does not mean that participants do not form specific expectations regarding their interaction partner. As we have little control over those expectations or influence the expectation by eliciting them, we opted against such a treatment. Results on trust and trustworthiness depending on the treatment scenario for the German participants are added in Appendix Figs. 3–5.

Our experimental setting has been approved by the ethics committee for experimental research at the University of Hamburg. The authors are happy to provide further details upon request. This experiment was part of a larger study. The other games inquired into were (in this order) altruism, risk behavior, reciprocity, cooperation, and honesty. For more information and the link to the original data, see El-Bialy et al. (2022) and Appendix A4.

One may wonder whether our German participants are themselves migrants or descendant of migrants. As we elicit the birthplace of the grandmothers of our participants, we could double-check that none of our German participants is a migrant or the direct descendant of a migrant.

The instructions were provided in German for the German participants. The complete data files as well as the complete instructions are available at the open science framework, see Appendix A4.

The experience of civil war spans from physical injuries to post-traumatic mental disorders that may cause depression and high distress levels (Galovski and Lyons 2004). On the other hand, individuals who experience conflict may also learn to cooperate with one another (Bauer et al. 2016). For these reasons, we control whether there is a link between distress and trust.

Controls for the location of the experiments can be found in Appendix Tables 3 and 4. Results remain robust overall. However, living in Stuttgart coincides with higher amounts of trust and conditional and unconditional trustworthiness compared to Leipzig. The latter city has an almost 2.5 times higher share of far right-wing party voters than the former (14.9% versus 6.1%) in its latest community election (City of Leipzig 2019, City of Stuttgart 2019). This may correlate with a stronger polarization in latter city, resulting in a generally lower level of trust and trustworthiness.

Seventeen participants did not answer the questions relating to social networks. We cannot distinguish between participants who do not engage in any kind of social networks and those who decided to leave the question unanswered due to unknown reasons. Because of this, we restrict our analysis to participants that actually engage in social networks. The percentages here indicated are calculated without taking these 17 observations into consideration.

Wilcoxon rank sum test: BonNet with Syrian and BonNet with German: p-value = 0.2916; BBNet with Syrian and BBNet with German: p-value = 0.8068; BriNet with Syrian and BriNet with German: p-value = 0.4684.

Wilcoxon rank sum test: BonNet with Syrian and BonNet with German: p-value = 0.4612; BBNet with Syrian and BBNet with German: p-value = 0.6957; BriNet with Syrian and BriNet with German: p-value = 0.0306. This significant difference appears in need of further clarification, yet it is likely that the non-parametric tests fail to reject the H0 due to the limited number of observations in the bonding network group.

A slope of 1 means that a trustee always returns the same amount of points that (s)he received from the trustor.

Wilcoxon rank sum test: BonNet with Syrian and BonNet with German: p-value = 0.0580; BBNet with Syrian and BBNet with German: p-value = 0.1536; BriNet with Syrian and BriNet with German: p-value = 0.6034.

One may argue that the slope of a linear estimation poorly characterizes conditional trustworthiness: trustees may increase their return rates the more points trustors send in the first place. This implies (at least) estimations including quadratic terms of the amounts sent. However, Appendix Fig. 2 shows the confidence intervals of return rates for all possible amounts sent and for each group of social network separately. The sequence of confidence intervals appears to follow a linear trend rather than a quadratic form.

The independent variables include Age groups, which is a categorical variable describing groups of age from 1 to 7, with the lowest age group being from 16 to 26 years and the highest one above 66 years. Education is a categorical variable that runs on a scale from 1, “learned to read and write without being schooled,” to 6, “post-graduate degree.” Male is a dummy variable describing the gender of the participants. Married is a dummy variable describing the marital status of participants. Length of residence is a continuous variable that describes the time spent in Germany in months (with the lowest being 10 months, the highest being 67 months, and the mean, 24 months). Importance of religion is a continuous variable running from 1 “not at all important” to 4 “very important” and denotes the importance of religion in life. Distress Level shows the average level of PTSD symptoms. Answers were coded on a scale from 1 (“not at all”) to 4 (“extremely”). If the average score is higher than 2.5, participants are considered symptomatic for PTSD. Finally, BBNet and BriNet denote those participants that are engaged either bonding and bridging activities or in exclusively bridging activities respectively. The baseline is a dummy for exclusively participating in bonding activities. WithGerman denotes the treatment scenario in which a Syrian participant is matched in the experiment with a German participant.

F-tests for linear hypothesis testing of the effect of interaction terms yield insignificant results: withGerman + withGerman * BBNet = 0, p-value = 0.763; withGerman + withGerman * BriNet = 0, p-value = 0.1437.

Endogeneity concerns are an issue in many social capital studies (see, Mouw 2006). Here, it could be the case that trust contributes to the formation of bonding networks, but it could also be the case that bonding networks contributes to the formation of trust. As far as we are concerned, this limitation is overcome with the implementation of random treatment scenarios.

For more information see Appendix A3.

One may argue that private housing may be subject to a selection process creating an endogeneity problem: refugees who are willing to integrate may not sort themselves into ethnic segregated communities and foster private housing as well as bridging activities. Our experience while working with the refugees is different. The timing and the exact location of the private housing offer is hardly influenced by the vast majority of refugees. Therefore, we consider private housing as an exogenous variable in our analysis. Further details are discussed in Appendix A2.

We cannot claim that this constitutes a causal relationship: it could be the case that refugees found a home because they are members of bridging social networks. Alternatively, it could be the case that because refugees interact with Germans in the neighborhood, they feel compelled to engage in bridging networks. Nonetheless, we consider this result as a useful insight, since it teaches us (at least) how refugees struggle with trusting the hosting society.

Refugees’ perceived distance to host society members are influenced to a large extent by their experiences with them. To take account of this, we add controls for distress level, private housing, and welcoming society to the other basic demographics. Controlling for experience, with host society members and the degree of prejudice and discrimination each respondent experienced could help explain a much larger portion of the variance, while increasing the accuracy of the estimates of the variables of interest. Appendix Tables 5 and 6 show OLS regressions on trust and trustworthiness controlling for “private housing” and “distress level” as a robustness check. Adding both controls to the regression models does not change the results substantially. Like this we can exclude that although they are correlated with choosing to bond and to bridge, they do not influence trust and trustworthiness significantly.

Wilcoxon rank sum tests: BonNet and BriNet (p-value = 0.0164); BonNet and BBNet (p-value = 0.0153); BBNet and BriNet (p-value = 0.6706). We also run a correlation test between bridging networks and the length of residence (Pearson’s product-moment correlation: ρ = 0.23; p-value = 0.01).

There is a negative and significant correlation of living in a refugee camp and bridging networks (ρ = 0.29; p-value < 0.001). Detailed information regarding the standard procedure for asylum seekers in Germany are summarized in Appendix A2.

References

Alesina A, La Ferrara E (2002) Who trusts others? J Public Econ 85(2):207–234

Allen R (2010) The bonding and bridging roles of religious institutions for refugees in a non-gateway context. Ethn Racial Stud 33:1049–1068

Andersen HS (2002) Excluded places: the interaction between segregation, urban decay and deprived neighbourhoods. Hous Theory Soc 19(3–4):153–169

Barr A, Serra D (2010) Corruption and culture: an experimental analysis. J Public Econ 94(11–12):862–869

Bauer M, Blattman C, Chytilova J, Henrich J, Miguel E, Mitts T (2016) Can war foster cooperation? Journal of Economic Perspectives 30(3):249–274

Behtoui A (2016) Beyond social ties: The impact of social capital on labour market outcomes for young Swedish people. J Sociol 52(4):711–724

Berg J, Dickhaut J, McCabe K (1995) Trust, reciprocity, and social history. Games Econom Behav 10(1):122–142

Bisin A, Verdier Thierry (2011) The economics of cultural transmission and socialization, in: Handbook of Social Economics, vol. 1, 339-416, Elsevier

Bock O, Baetge I, Nicklisch A (2014) hroot: Hamburg registration and organization online tool. Eur Econ Rev 71:117–120

Bolt G, Phillips D, Van Kempen R (2010) Housing policy, (de)segregation and social mixing: An International Perspective. Hous Stud 25(2):129–135

Boyd M (1989) Family and personal networks in international migration: recent developments and new agendas. Int Migr Rev 23(3):638–670

Boyle PJ, Kulu H, Cooke T, Gayle V, Mulder CH (2008) Moving and union dissolution. Demography 45(1):209–222

Brandts J, Charness G (2011) The strategy versus the direct-response method: a first survey of experimental comparisons. Exp Econ 14:375–398

Brell C, Dustmann C, Preston I (2020) The labor market integration of refugee migrants in high-income countries. J Econ Perspect 34(1):94–121

Buchan NR, Croson RT, Solnick S (2008) Trust and gender: an examination of behavior and beliefs in the Investment Game. J Econ Behav Organ 68(3–4):466–476

Burt R (1997) The contingent value of social capital. Adm Sci Q 42(2):339–365

Cettolin E, Suetens S (2019) Return on trust is lower for immigrants. Econ J 129(621):1992–2009

City of Leipzig (2019). Wahlergebnis der Stadtratswahl am 26.05.2019 in Leipzig. https://www.leipzig.de/buergerservice-und-verwaltung/wahlen-in-leipzig/stadtratswahlen/stadtratswahl-2019/wahlergebnis-stadt-leipzig/. Accessed 06 July 2023

City of Stuttgart (2019). Die Gemeinderatswahl am 26. Mai 2019 in Stuttgart. https://www.domino1.stuttgart.de/web/komunis/komunissde.nsf/fc223e09e4cb691ac125723c003bfb31/1cdcc4940633796ac12585660011951d/$FILE/bs502_.PDF. Accessed 06 July 2023

Coffé H, Geys B (2007) Toward an empirical characterization of bridging and bonding social capital. Nonprofit Volunt Sect Q 36(1):121–139

Coleman JS (1988) Social capital in the creation of human capital. Am J Sociol 94(Suppl):S95–S120

Edin PA, Fredriksson P, Åslund O (2004) Settlement policies and the economic success of immigrants. J Popul Econ 17:133–155

El-Bialy N, Aranda EF, Nicklisch A, Saleh L, Voigt S (2022) A sense of no future in an uncertain present: altruism and risk-seeking among Syrian refugees in Jordan. J Refug Stud 35(1):159–194

Elliott S, Yusuf I (2014) Yes, we can; but together: social capital and refugee resettlement. Kotuitui: New Zealand J Soc Sci Online 9(2):101–110

Fehr E (2009) On the economics and biology of trust. J Eur Econ Assoc 7(2–3):235–266

Fehr E, Gächter S (1998) Reciprocity and economics: the economic implications of Homo Reciprocans. Eur Econ Rev 42(3–5):845

Fershtman C, Gneezy U, Verboven F (2005) Discrimination and nepotism: the efficiency of the anonymity rule. J Leg Stud 34(2):371–396

Fischbacher U, Gächter S, Quercia S (2012) The behavioral validity of the strategy method in public good experiments. J Econ Psychol 33(4):897–913

Foner N, Alba R (2008) Immigrant religion in the U.S. and Western Europe: bridge or barrier to inclusion? Int Migration Rev 42(2):360–392

Galovski T, Lyons JA (2004) Psychological sequelae of combat violence: a review of the impact of PTSD on the veteran’s family and possible interventions. Aggress Violent Beh 9:477–501

Granovetter MS (1973) The strength of weak ties. Am J Sociol 78(6):1360–1380

Greiner B, Zednik A (2019) Trust and age: an experiment with current and former students. Econ Lett 181:37–39

Hannafi C, Marouani MA (2022) Social integration of Syrian refugees and their intention to stay in Germany. J Popul Econ 36(2):581–607

Hartog J, Zorlu A (2009) How important is homeland education for refugees’ economic position in The Netherlands? J Popul Econ 22:219–246

Hirschman C (2004) The role of religion in the origins and adaptation of immigrant groups in the United States. Int Migr Rev 38(3):1206–1233

Hurlbert J, Haines V, Beggs J (2000) Core networks and tie activation: what kinds of routine networks allocate resources in non-routine situations? Am Sociol Rev 65(4):598

Jeworrek S, Leisen BJ, Mertins V (2021) Gift-exchange in society and the social integration of refugees–Evidence from a survey, a laboratory, and a field experiment. J Econ Behav Organ 192:482–499. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2021.10.025

Kasarda JD, Janowitz M (1974) Community attachment in mass society. Am Sociol Rev 39:328–339

Khadjavi M, Tjaden JD (2018) Setting the bar-an experimental investigation of immigration requirements. J Public Econ 165:160–169

Larsen L, Harlan S, Bolin R, Hackett EJ, Hope D, Kirby A, Wolf S (2004) Bonding and Bridging: understanding the relationship between social capital and civic action. J Plan Educ Res 24(1):64–77

Lépine A, Estevan F (2021) Do ability peer effects matter for academic and labor market outcomes? Labour Econ 71:102022

Lindström M (2012) Marital status and generalized trust in other people: a population-based study. Soc Sci J 49(1):20–23

Marmaros D, Sacerdote B (2002) Peer and social networks in job search. Eur Econ Rev 46(4–5):870–879

Menahem G, Doron G, Haim DI (2011) Bonding and bridging associational social capital and the financial performance of local authorities in Israel. Public Manag Rev 13(5):659–681

Mouw T (2006) Estimating the causal effect of social capital: a review of recent research. Ann Rev Sociol 32:79–102

Paxton P (2002) Social capital and democracy: An interdependent relationship. American sociological review 67(4):254—277

Portes A, Sensenbrenner J (1993) Embeddedness and immigration: notes on the social determinants of economic action. Am J Sociol 98:1320–1350

Putnam RD (2000) Bowling alone: the collapse and revival of American community. Simon and Schuster, New York

Ryan L, Sales R, Tilki M, Siara B (2008) Social networks, social support and social capital: The experiences of recent Polish migrants in London. Sociology 42(4):672–690

Sanders JM, Nee V (1996) Immigrant self-employment: The family as social capital and the value of human capital. American sociological review 61(2):231–249

Schulz AJ, Israel BA, Zenk SN, Parker EA, Lichtenstein R, Shellman-Weir S, A. B. LK (2006) Psychosocial stress and social support as mediators of relationships between income, length of residence and depressive symptoms among African American women on Detroit’s eastside. Soc Sci Med 62(2):510–522

Scott J (1988) Social Network Analysis. Sociology 22(1):109–127

Simpson L (2004) Statistics of racial segregation: measures, evidence and policy. Urban Stud 41(3):661–681

Staveren I, Knorringa P (2007) Unpacking social capital in economic development: how social relations matter. Rev Soc Econ 65(1):107–135

Stolle D, Rochon TR (1998) Are all associations alike? Member diversity, associational type, and the creation of social capital. American Behavioral Scientist 42(1):47–65

Strang A, Quinn N (2021) Integration or Isolation? Refugees’ Social Connections and Wellbeing. J Refugee Stud 34(1):328–353

Tan JH, Vogel C (2008) Religion and trust: an experimental study. J Econ Psychol 29(6):832–848

Torres JM, Casey JA (2017) The centrality of social ties to climate migration and mental health. BMC Public Health 17(1):1–10

Turner JC, Brown RJ, Tajfel H (1979) Social comparison and group interest in in-group favouritism. Eur J Soc Psychol 9(2):187–204

Wacquant LJ (1993) Urban outcasts: stigma and division in the black American ghetto and the French urban periphery. Int J Urban Reg Res 17(3):366–383

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Omar Elkhawas, Ahmed Jarkeen, Mohanad Hamar, Menna Magdi, Hashem Nabas, and Galila Nasser for their assistance in conducting the experiments in the field and Asmaa Ezzat, Enisa Halili, Mazen Hassan, Katharina Hembach, Sarah Mansour, Seif Eldin Radwan, and Parisa Shaheen for their contribution in translating and improving the interface of the experiments in different languages. Special thanks go to Nicolai Wacker for his support in conducting the experiments and legal input throughout the paper, and to Olaf Bock and Thais Hamasaki for their technical support and all programing tasks incurred in running the experiments. Critique and suggestions from the conference participants at the Annual meeting of the Society for Experimental Economics in Duesseldorf, and in particular Marek Endrich, Jerg Gutmann, Tobias Hlobil, Nada Maamoun, Stephan Michel, and Konstantinos Pilpilidis, are gratefully acknowledged. The authors also thank editor Kompal Sinha and two reviewers. The authors thank the VolkswagenFoundation for supporting their research within the framework of its project line on “Experience of Violence, Trauma Relief and Commemorative Culture – Cooperative Research Projects on the Arab Region.” The authors are happy to provide further details upon request.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Applied Sciences of the Grisons

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Our experimental setting has been approved by the ethics committee for experimental research at the University of Hamburg.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Responsible editor: Kompal Sinha

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

El-Bialy, N., Aranda, E.F., Nicklisch, A. et al. No man is an island: trust, trustworthiness, and social networks among refugees in Germany. J Popul Econ 36, 2429–2455 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-023-00969-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-023-00969-7