Abstract

Policy-makers wanting to support child development can choose to adjust the quantity or quality of publicly funded universal pre-school. To assess the impact of such changes, we estimate the effects of an increase in free pre-school education in England of about 3.5 months at age 3 on children’s school achievement at age 5. We exploit date-of-birth discontinuities that create variation in the length and starting age of free pre-school using administrative school records linked to nursery characteristics. Estimated effects are small overall, but the impact of the additional term is substantially larger in settings with the highest inspection quality rating but not in settings with highly qualified staff. Estimated effects fade out by age 7.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Publicly funded early childhood education and care (ECEC) is an established policy in many developed economies. The first public ECEC programmes were small-scale, randomised interventions targeted at disadvantaged children in the USA in the 1960s, which showed strong impacts on educational achievement and later outcomes (Barnett 1995; Heckman et al. 2010; Karoly and Kilburn 2006). The evidence from these programmes supported an expansion into universal provision in many countries around the world. With universal ECEC established, policy-makers are now seeking to optimise its impact on children’s development.

One relevant option available to policy-makers is expanding the quantity of free care made available to children before they start school, either in terms of the age at which children start pre-school or the number of hours provided. We offer evidence on the impact of marginally extending the length of programmes by about 3.5 months on children’s educational attainment at ages 5 and 7. To do this, we exploit UK rules governing eligibility for an extra term of free part-time pre-school at age 3 depending on children’s date-of-birth. This enables us to use a regression discontinuity approach to give a causal estimate of the impact of an earlier start in and longer duration of ECEC. Related UK evidence finds that each month of additional full-time education in school at age 4 raises educational achievement at age 5 in the order of 6–9% of a standard deviation (Cornelissen and Dustmann 2019), suggesting that this relatively small extra dosage of free part-time ECEC could have substantial effects.Footnote 1

A second lever available to policy-makers is to adjust childcare quality. It has become common to assert that pre-school should be “high quality” (see President Barack Obama’s 2012 State of the Union pledge “to make high-quality pre-school available to every single child in America”) but we know relatively little about the programme features that will enable universal provision to achieve the biggest educational impact. To investigate this we ask whether the effect of eligibility for an extra term of pre-school varies with characteristics of the setting that are often used to indicate quality. Specifically, we consider staff qualifications and ratings from nationwide nursery inspections. Previous studies are mostly based on researcher-collected quality indicators, which are typically available only in small datasets and are therefore of limited practical relevance. Instead, the quality measures we use are collected because of the existence in England (as well as many other countries) of a regulatory framework governing both school inspections and staff qualifications (OECD 2015). They are therefore readily available to policy-makers.

Our interest in childcare quality is further motivated by mixed international evidence on the impact of universal provision of ECEC on children’s outcomes with some studies finding positive and others no or even negative effects.Footnote 2 Given this ambiguous evidence, understanding the features of successful universal ECEC systems is essential. The idea that only high quality childcare is beneficial very often rests on ex-post comparisons between the characteristics of successful programmes (e.g. Norway) with those of programmes found to be ineffective (e.g. Quebec), and resonates strongly with policy-makers. Despite the intuitive appeal of this argument, however, we cannot point out precisely what features of early education provision define its quality and whether quality indicators are causally positively associated with child outcomes (Cascio 2015; Sabol et al. 2013).

Our analysis takes place in the English context where universal ECEC comes in the form of the free entitlement to part-time childcare (hereafter the “free entitlement”), a subsidy that costs the government around £2bn per year (Department for Education 2013).Footnote 3 The policy was rolled out across England in the early 2000s, and 94% of children benefit from part-time ECEC at age 3, delivered in public and private sector settings (National Audit Office 2016).

We use administrative data from the National Pupil Database to measure the effects of eligibility for childcare and its quality on teacher-assessed measures of academic and social skills recorded at the end of the first year of school, at age 5, and on test results in English, Maths and Science at age 7. We have information on the precise date of birth for four cohorts of children born close to the relevant eligibility cutoff dates who started school from academic years 2008 to 2011. Observations on 270,000 children are linked to information on the characteristics of childcare settings attended at age 4, including staff qualifications and inspection ratings published by the English education regulator Ofsted.

To assess the causal effect of eligibility to an extra term of part-time childcare (and the earlier starting age that this implies) we use a regression discontinuity design, exploiting variation in eligibility to a free place due to strictly enforced date-of-birth discontinuities. We find that eligibility for an extra term of childcare leads to a small increase in the probability that a child reaches the expected level of competencies after the first year in primary school, at age 5, compared to children not eligible for the extra term. Heterogeneity analysis reveals stronger effects on boys, but no significant pattern in relation to children’s socio-economic characteristics. In line with much of the early child development literature we find that results fade out quickly and are no longer evident in outcomes measured at age 7.

To assess the effect of an extra term (and earlier start) in settings of different quality we control comprehensively for observed and unobserved differences across children attending different quality settings. We test whether the effect of an extra term of childcare varies according to the presence of a carer with a degree-level qualification, a level of qualification of particular policy focus in the UK,Footnote 4 and according to the quality rating of the setting determined through nursery inspection. We do not find any evidence that the effects of eligibility vary according to the qualification level of staff working with 3–4-year-olds, but attending an Outstanding setting (the top inspection rating) brings an additional benefit from eligibility to an extra term; it increases the probability of working at or above the expected levels of achievement at age 5 by 3–4 times the baseline effect.

In studying the impact of an extra dose of ECEC and its quality on children’s educational outcomes, this paper contributes to a number of literatures. First, it considers the impact of extending pre-school programmes by a few months; this is a relevant margin for policy-makers in countries where universal ECEC is established. Much of the work done so far on varying the quantity of provision compares 2-year programmes with 1-year programmes, an expensive policy change (Arteaga et al. 2014; Shah et al. 2017). Few studies on the impact of dosage are able to make use of quasi-experimental methods as we do. Further, we enhance the evaluation of pre-school programmes by investigating not just whether programmes make a difference, but which programme features might lead to success. Few studies within economics currently question whether variation in setting quality within the same childcare system can be linked to variations in child outcomes (Duncan and Magnuson 2013). We speak to this question. The administrative data that we have allows us to explore policy-relevant measures that capture both structural and process concepts of quality. Structural regulations on staff qualifications are more straightforward to put in place than expensive nationwide inspections, so understanding the relative merits of each is of crucial relevance for policy-making. Our results imply that inspection judgements can contain valuable information and encourages both researchers and policy-makers to continue to analyse and develop them.

More broadly, our results on dosage speak to the literature on the optimal length and timing of education. This literature has hitherto been focused on the optimal age to start school, whereas our focus reflects the new reality of widespread universal pre-school with many children starting education in pre-school at an early age.

Our results on quality add to the literature on school and teacher effectiveness, which so far has focused on the school years (Walters 2015 on Head Start is one exception). This literature generally finds big differences in teacher effectiveness but struggles to identify measurable teacher characteristics such as education and experience that drive differences in effectiveness (Rockoff 2004; Rivkin et al.2005). In contrast, Dobbie and Fryer (2013) are able to identify particular practices that drive the differing success of charter schools but confirm that staff qualifications and pupil-teacher ratios do not have predictive power.

The next section discusses the literature on childcare expansion and quality. Section 3 describes the institutional background to the English education and childcare sector, and more specifically, the free entitlement. Section 4 lays out our empirical strategy, based on a regression discontinuity design, while Section 5 provides information on the data used. Section 6 describes our results, and Section 7 concludes.

2 Previous literature

Studies of ECEC effectiveness often discuss the importance of the “dosage” of ECEC that children experience. There are several aspects of this, the length of day, the number of days attended per week and weeks per year, and the age that children start pre-school. If we think of ECEC as an investment in children’s human capital it is natural to think that the more time spent in ECEC the better. However, it is clear that this may not be true along all the margins mentioned above; long hours spent in ECEC on each day have been associated with negative behavioural outcomes (Baker et al. 2019; Datta Gupta and Simonsen 2010) and there is a tension between starting early to make the most of rapid neural development (Doyle et al. 2009) but at the same time not starting children “too” young and putting them at risk of poor attachment (Belsky 1988).

We are interested in the impact of an additional term spent in ECEC, and the slightly younger start date that this implies. There are a number of descriptive studies which investigate whether having 1 or 2 years of pre-school education is most effective, with children typically starting either at age 3 or 4.Footnote 5 Few studies have adopted quasi-experi- mental methods to understand the impact of longer programme duration. An exception is Kühlne and Oberfichtner (2017) who exploit a fuzzy RDD in Germany that leads to a 5-month difference in the age at start/number of months of ECEC received. A variety of outcomes are studied and no short- or medium-term impacts are found.

Quasi-experimental approaches have more commonly been used to assess the appropriate starting age of formal schooling. We have already noted the positive effects of each month of infant schooling found by Cornelissen and Dustmann (2019). This paper uses data on children who started school in 2005 when variation in school starting age by term of birth was relatively common. This variation is used to identify the combined effect of the age at starting school and the length of time spent in the first year of school (the Reception year). Leuven et al. (2010) adopt a similar research design and find that each additional month raises test scores at age 6 by 5–6% of a standard deviation in the Netherlands. Black et al. (2011) and Fredriksson and Öckert (2014) use discontinuity approaches to estimate whether starting formal schooling earlier or later is beneficial for educational outcomes and earnings, holding constant the total amount of schooling obtained. Both find that delaying school entry raises educational outcomes. Notice that this implies that estimating the combined effect of an extra term and earlier starting age may bias against finding any impact. Taken together, there has been very little evidence on the educational impact of small increases in the duration of pre-school programmes. We argue it is small (and therefore relatively inexpensive) changes that are most relevant for policy-makers today. The causal evidence has been focused on optimal school start, whereas most children now experience educational provision before the start of full-time compulsory school. Our approach enables us to add robust evidence on the optimal timing and duration of ECEC.

The other aspect we consider is the impact of ECEC quality. Within the economics literature the conclusion that pre-school quality matters is generally reached by comparing the features of programmes which show substantive benefits such as those in Norway (Havnes and Mogstad 2011), Spain (Felfe et al. 2015) Oklahoma and Georgia (Cascio and Schanzenbach 2013), with those with no benefits such as Quebec (Baker et al. 2008, 2019; Haeck et al. 2018), and Denmark (Datta Gupta and Simonsen 2010). In this spirit (Cascio 2015) compares a number of US states and while she demonstrates that compared to contemporary targeted programmes universal systems have much greater benefits for disadvantaged children, it is not possible to identify the precise features of programmes that lead to success.

In contrast we focus on two specific measures of quality; staff qualifications and government inspection ratings. Staff qualifications are measured as the presence or share of staff with a relevant degree level or equivalent qualification in the setting. Having staff with qualifications at this level is often considered best practice,Footnote 6 although the evidence for this prescription is not strong. Non-experimental work from the USA has found weak evidence that high staff qualifications matter for children’s outcomes (Early et al. 2007; Mashburn et al. 2008) and the European review by Ulferts and Anders (2016) finds evidence that broader measures of qualifications are important. Evidence from the UK suggests that staff qualified to graduate level are able to produce better quality as measured through classroom observation (Mathers et al. 2011; Siraj-Blatchford et al.2005), although the direct link between higher-level qualifications among staff and children’s development 1 year later is quite weak (Blanden et al. 2017).

Staff qualifications are a fundamental measure of structural quality (the inputs used). Pre-school quality ratings, on the other hand, usually incorporate elements of both structural and process quality, i.e. they take into account the child’s experience in the setting as well as the setting’s inputs. Both regulation and inspection are used to promote quality improvement and have become more widespread in recent years throughout OECD countries (OECD 2015; Gambaro et al. 2014). They can be either enforced by law (as in our case) or through voluntary schemes, such as the QRIS (Quality Rating and Improvement System) in the USA.Footnote 7 The particular inspections we consider, performed by the English Office for Standards in Education (Ofsted) and described in more detail in the next section, assess whether settings are meeting national regulations on staff-child ratios, staff qualifications, health and safety and other policies as well as observing the interactions between children and carers and the extent to which children are meeting the early development goals set by government (Mathers et al. 2012). Ofsted awards an overall grade ranging from 1, “Outstanding” to 4, “Inadequate” for overall effectiveness. The existing evidence from England on the relationship between Ofsted ratings, quality and children’s outcomes is inconclusive. Mathers et al. (2012) find that, on average, settings graded as “Outstanding” by Ofsted achieve higher observed quality scores than “Good” settings, which do better than settings graded as “Satisfactory”. However, those graded as “Inadequate” do not have the lowest quality ratings on average. Hopkin et al. (2010) examine the impact of childcare Ofsted ratings on a range of cognitive tests administered as part of a survey as well as teacher graded assessments of the children collected from their schools at age 5 and find no link. Neither of these studies is based on representative samples or causal identification techniques.

3 Institutional background

Since 2004 all English Local Authorities (equivalent to school districts) have been funded to provide universal part-time early years education and care for children from the term after their third birthday.Footnote 8 For the cohorts we study here this was 12.5 h for 38 weeks a year until 2010, extending to 15 h per week from September 2010 onwards.Footnote 9 In further expansions beyond the period we study, disadvantaged 2-year-olds have also been offered 15 h of free care since 2013 and since September 2017 working families have been entitled to 30 h.Footnote 10

In England all children enter primary school in the academic year in which they turn 5 (the Reception year). In recent years most schools have adopted a unique intake date in September. This implies that irrespective of their date of birth, all children within a school-cohort (going from 1st September to 31st August) start formal schooling at the same time (but at a different age). In contrast, eligibility for free part-time pre-school care changes discontinuously across the year; children born between 1st September and 31st December are entitled to claim their free hours from the following January, children born between 1st January and 31st March from April, while those born between 1st April and 31st August are allowed to claim their entitlement only from September of the following school year.Footnote 11 To the extent that children’s participation is governed by their entitlement, children who experience more months in free ECEC will also start at a younger age. Our analysis considers only children born around the 31st December and 31st March cutoffs, who are different in respect of their eligibility for free early education and care but start school at the same time and belong to the same school cohort. In contrast, those born around the August cutoff belong to different school cohorts because September-borns start a year later than August-borns. Including children born around the August cutoff would confuse nursery eligibility effects with those associated with age at school start.

Around half of children are provided their free place in the public sector and the other half in the private sector, with eligibility rules being the same across both sectors, although (Campbell et al. 2018) show that in practice private sector settings are more willing to accommodate new children in January (and likely in April too). In this paper we focus on the private sector to be able to exploit its wider variation in the quality measures we use. These occur because institutional arrangements are more flexible in the private than the public sector. We nonetheless check results on the impact of eligibility for both sectors, see footnote 26. Whether children attend childcare in the public or private sector will depend on availability where they live, the preferences of parents and the hours of care required.Footnote 12 Opening hours in the public sector are restrictive, never exceeding school hours (about 6.5 h a day) and sometimes children are offered only morning or afternoon sessions. In contrast the private sector can provide full-time care. Moreover, public sector settings must have a qualified teacher present, and the adult-child ratio is set to 1:13. Requirements for qualifications are lower in private settings, but if there is no qualified teacher or person with Early Years Professional Status (EYPS)Footnote 13 present then the ratio of adult per child is increased to 1:8 (Gambaro et al. 2015). Notably, the EYPS does not qualify individuals to work as a nursery teacher in the public sector, implying that the two qualifications are not universally viewed as comparable.

All providers who receive government funding are required to follow a common curriculum, the Early Years Foundation Stage. The curriculum emphasises learning through play, ensures that a range of stimulating activities are provided and that children’s development across a range of areas is encouraged and monitored. All settings are subject to inspection by the government regulator Ofsted (Office for Standards in Education), roughly every 4 years. Ofsted states the purpose of its inspections is “to judge the overall quality and standards of the early years provision in line with the principles and requirements of the Statutory Framework for the Early Years Foundation Stage” (Ofsted 2015). Inspection judgements for private settings are based on one-day visits which gather evidence by observation, reviewing policies, discussion with staff and parents and by reviewing the development of example children with a focus on the disadvantaged (Ofsted 2015). Public sector provision in nursery classes is inspected as part of the whole school’s inspection, which leads to doubt about the acccuracy of judgements, providing a further rationale for our focus on private provision.

4 Empirical strategy

Our empirical analysis proceeds in two steps. First, we establish whether entitlement to an extra term of free part-time early education and the earlier start date this implies has a significant effect on child educational attainment. Then we consider whether the effect of eligibility varies according to the quality of the pre-school setting to understand whether quality—as measured in our data—matters for children’s outcomes.

Access to free part-time early education and care is based on strict date-of-birth rules. This enables us to pursue a sharp Regression Discontinuity Design (Imbens and Lemieux 2008; Thistlethwaite and Campbell 1960) to assess the impact of eligibility for an additional term of the free entitlement on educational outcomes.

We define an indicator variable Ti which takes value 1 when the child’s date of birth ai is before or on the cutoff date \(\bar {a}\) which entitles them to a free place at the start of the following school term. Children whose birth date is after the cutoff will have to wait another term before becoming eligible for the subsidy, so that for them Ti has a value of 0.

These children not only receive a term less childcare than those with Ti = 1, they are also older when they start nursery. We cannot separately identify these two aspects. As shown by Cornelissen and Dustmann (2019), no single policy will allow the separate identification of education duration, age at start and age at test. As already noted there is evidence that children who start nursery older (and are tested older) do better, so as time spent at nursery goes hand-in-hand with an earlier start it is possible that our estimates understate the impact of programme duration.

A further consideration regarding age is that because eligibility for an extra term of childcare is a function of date of birth and all children take their assessments at the same time, date of birth determines age at test. Eligible children will be, by construction, older than non-eligible children, and owing to the well-documented positive relationship between age at test and test scores (Leuven et al. 2010; Crawford et al. 2014) they will have better outcomes. It is therefore essential that we control for a flexible function of date of birth. Although we assume that eligibility is unrelated to the child’s observed and unobserved characteristics, all our specifications also control for Xi, a vector of individual-level characteristics; this also improves the precision of our estimates. Our estimation equation is thus:

where the outcome of child i, Yi, is a function of eligibility Ti, date of birth ai, a vector of child characteristics Xi and εi is a random error term. All our models contain school fixed-effects (and by implication Local Authority fixed effects) and therefore purge the estimates of a number of unobserved factors that vary at the school and LA level. Standard errors are clustered at the level of date of birth and school. The clustering by date of birth is particularly important as this is the variable which defines our treatment, i.e. eligibility for an extra term of childcare.

Following Altonji and Mansfield (2018), we augment the specification above using the averages of individual characteristics of children in different settings, \(\overline {X_{j}}\). This is important in situations where there might be sorting of individuals into different groups (such as pre-schools), and the outcome is a function of individual as well as group characteristics. So, for each child i who attends pre-school j our model becomes:

The graphical analysis presented in the next section suggests that f(⋅) is a linear function of date of birth and we use this formulation in most of our analysis. We also run models where f(⋅) is specified as a quadratic function of date of birth or as a linear function whose slope is allowed to change at the cutoff. Our data has the advantage of a very large sample size which means we can restrict estimates to births very close to the discontinuity (within 4 weeks either side of the cutoff), thereby minimising the sensitivity of our results to the specification of f(⋅). Related to this, we will show how our estimates change with the size of the data window around the cutoff.

In order for specification (3) to produce an estimate of the causal effect of eligibility to an extra term of childcare, the treatment must be as good as randomly assigned close to the cutoff. This assumption can be checked in two ways; by showing that eligibility is orthogonal with respect to the observed determinants of test scores, and by checking for changes in the density function of the running variable (date of birth) around the cutoff. If births are concentrated on one side of the eligibility cutoff, this might suggest that families can choose the date of birth of their children to take advantage of the policy, implying that those receiving the treatment have selected into it. In Section 5.4 we provide evidence that there is no systematic association between observed characteristics and date of birth and that the frequency of births is smooth around the cutoff.

Equation (3) allows us to estimate β, the effect of eligibility on child outcomes and is an intention-to-treat effect (ITT). We are also interested in the effect of ECEC attendance, that is the effect of treatment on the treated (TT). However, to achieve this we would need information on when precisely children start attending pre-school and our data does not provide this.Footnote 14 Instead, we use information from a separate dataset, the Family Resources Survey, to show the relationship between eligibility and attendance close to the eligibility threshold. We then use these estimates to give an idea of the effect of ECEC attendance on child outcomes or the TT. As eligibility might affect child outcomes through channels other than attendance, such as the number of hours of early education or family income, our main focus remains on the effect of eligibility or the ITT.

The second step in our analysis is to examine whether the quality of the pre-school setting influences the effect of eligibility. To do this, we include in our estimation the available measures of setting quality, Qj, as well as interactions of Qj and eligibility status. Our model thus becomes:

Here the coefficient ψ shows the association between the measure of setting quality and child outcomes. This is interesting per se, but it cannot be given a causal interpretation because even though we use setting-level averages of child observable characteristics to control for sorting, we cannot totally exclude the possibility that children choose different pre-schools on the basis of their unobserved characteristics. In other words, the coefficient on Qj captures unobserved differences across children that attend settings with different quality characteristics, as well as the true effects of quality on outcomes.

Our main interest is instead on the coefficient ϕ. This represents how the eligibility effect varies with the quality of the setting. It may not, however, capture the causal effect of quality of pre-school education on children’s outcomes if the returns to an extra term in pre-school are different in higher quality nurseries because of sorting by background characteristics such as socio-economic status, for example because more advantaged children benefit more. However, we can say that ϕ picks up a causal effect of quality if one of two conditions are met: either 1) sorting is completely controlled for, or 2) the effect of eligibility is not heterogeneous with respect to those individual characteristics we cannot control for, but that influence the sorting into settings. Admittedly, our administrative data set only contains a limited number of observable family and child characteristics, but as well as controlling for sorting through \(\overline {X_{j}}\), we control for it through Qj—recall that this captures unobserved characteristics of children attending different quality settings. We also show that the eligibility effect does not vary with the observable characteristics of the child. This makes us confident that our novel approach comes close to capturing the genuine effect of ECEC quality.

5 Data

5.1 National Pupil Database

Our analysis is based on data from the National Pupil Database (NPD), an administrative dataset containing information on the educational achievement and background of all children attending public (state) schools in England (about 93% of children). It includes child characteristics including gender, eligibility for means-tested free school meals (FSM), ethnicity, whether the first language spoken at home is English, and the level of income deprivation in the neighbourhood around the child’s postcode of residence. FSM eligibility will be used to distinguish low from higher income families, and although it has its limitations it is a reasonable proxy (Hobbs and Vignoles 2010; Ilie et al. 2017). The dataset is longitudinal, in that it follows each child over the primary and secondary school years, and contains school and Local Authority identifiers.

We focus our analysis on educational attainment at the end of the Reception year, when children are approximately 5 years old, because this provides the first available measure of their development. At the end of their first year in school, all children are assessed by their teacher in the different areas of learning covered by the Foundation Stage Profile (FSP) curriculum (Department for Education 2012a, ??). Teacher assessments are moderated within the Local Authority to provide quality assurance. There are 13 assessment scales, each with a range between 1 and 9, grouped into six areas: personal, social and emotional development; communication, language and literacy; problem solving, reasoning and numeracy; knowledge and understanding of the world; physical development, and creative development. Children who score 6 points or above in all 13 scales are defined as “working within the Early Learning Goals”, implying they are at least meeting the expected level of achievement. We will define them as working at or above the expected level. Children with a score of 9 in at least one of the scales are deemed to be working “beyond the ELGs”, so will be categorised as working beyond the expected level. Finally, those with a score of 1 to 3 in at least one of the assessment scales will be classified as working towards the expected level. The assessments can also be summed up to give a total score of up to 117 points, but we will mainly focus on the threshold measures because they allow us to capture effects at different points in the ability distribution.

We also report results for the assessments obtained 2 years later, when children are aged 7 and reach the end of a part of the curriculum called Key Stage 1 (KS1).Footnote 15 Teachers assess children in Reading, Writing, Maths and Science, based on formal assessments and knowledge of the child and with moderation from the Local Authority. Attainment is graded in terms of levels (0, 1, 2c, 2b, 2a and 3), where children of this age are expected to reach level 2b, while level 3 is regarded as exceeding expectations. The levels can also be transformed into a total KS1 point score using a standard scoring system.

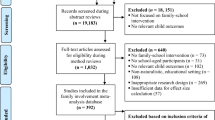

We have access to NPD extracts including date of birth for four cohorts of children starting school between the academic years 2008/09 and 2011/12. We use data on mainstream schools only, i.e. our sample excludes schools which cater exclusively for children with special needs. Due to data access restrictions, we only have information on a subsample of all children from each cohort, including children born up to 4 weeks before and after the 31st December and 31st March cutoffs, for children born in 16 weeks of the year in total. From this sample we exclude duplicate cases and observations with missing information on the FSP scores (less than 1% of the sample), children born on the first day of the cutoff,Footnote 16 and children who attend schools with staggered school-starting policies where school entry coincides with the eligibility cutoff.Footnote 17

5.2 Early Years Census and Ofsted data

We merge children’s school outcomes contained in the NPD data to the Early Years Census (EYC) which uses the same child identifiers as the NPD and contains data from the year before they start school for all children receiving the free entitlement in the private sector (the focus of our analysis).Footnote 18 Our sample of children attending private pre-school settings includes 284,544 children who make up about 47% of the total sample of children for whom we have a record of pre-school attendance.

From the EYC we have information on teaching qualifications and group size. Specifically, for all children attending pre-school education in the private sector, we have information on the number of staff who are qualified teachers (QTS) and who have Early Years Professional Status (EYPS, see footnote 13). Questions on qualifications are asked with respect to all staff (including managers) and also more specifically about those carers working with the children who receive the free entitlement, i.e. teaching staff. We mostly use the variables that refer to teaching staff working with 3- and 4-year-olds, but results are robust to broader definitions.Footnote 19 We also make use of information on the total number of staff and children to construct a ratio of 3- and 4-year-olds per member of teaching staff. As well as being of interest in itself, this variable is important to isolate the effect of teacher qualifications from group size, as the two are mechanically linked through policy guidelines (see Section 3). Due to missing information on some of these variables and measurement issues, we exclude very large or small pre-school settings and those that have very large or small pupil to teacher ratios (7% of observations), leading to a final sample of 265,679 observations.

Further, we link information on Ofsted ratings to our data. We have data on all assessments of private settings carried out by the regulator between 2005 and 2011, and we match each child to the rating for their setting that is closest in time to their attendance.Footnote 20 As well as providing a 1–4 (Outstanding to Inadequate) rating of overall effectiveness, the same categorical judgements are given for different sub-areas which we exploit to generate a continuous measure of the Ofsted ratings which ranges from 6 to 24, where 24 points imply an Outstanding judgement across all areas.Footnote 21 We can match Ofsted ratings to 80% of children who attend pre-school in private sector settings. We include observations for which Ofsted ratings are missing in our analysis and use a dummy to distinguish them from the rest.

5.3 Descriptive statistics

Our analysis considers the effect of eligibility for childcare on the educational outcomes of children who attend early education in the private sector. In Table 8 in the Appendix we present summary statistics of observable characteristics of children in our sample and compare them to the total population of children attending pre-school education to assess how children in private sector childcare differ from the population average. The main differences are by family and social background, with low-income children being less represented in the private sector. For instance, we observe 10% of the children in private settings are eligible for free school meals, while this percentage is 17.2 across both private and state sectors. Similarly, among children attending private settings, we have a lower percentage of pupils who speak English as an additional language and a higher percentage who are from a White British background, than in the general population.

Table 9 in the Appendix compares child outcomes at age 5 between all children and children in private sector settings. Children who attend nurseries in the private sector have higher scores, on average, than all children attending pre-school. For example, the standardised total FSP score (standardised using the overall year mean and standard deviation) is 0.21 for children from private sector nurseries and 0.10 among all children in ECEC. This is not a clear indication that private sector nurseries are higher quality, as we saw earlier that children attending these nurseries tend to come from less disadvantaged family backgrounds. As we would expect at age 5, girls outperform boys in all outcome measures, with the gap being generally smaller in numeracy than in literacy.

Table 10 in the Appendix focuses on children attending private sector nurseries and provides information about our measures of quality. There is substantial variation across the dimensions of quality we consider, i.e. in terms of teacher qualifications and Ofsted ratings. The proportion of children in private settings with at least one Qualified Teacher is 22%, while 12% have an Early Years Professional in the setting. This compares unfavourably with public sector settings, where settings always require a Qualified Teacher, and with the situation in most other countries (Gambaro et al. 2014). In terms of nursery inspection ratings, 13% of children attend a setting rated Outstanding, with the majority of children being in settings rated Good (55%), 15% are in settings rated Satisfactory, and only 1.5% in settings rated Inadequate. In our analysis we therefore focus on the consequence of attending an Outstanding or Good setting compared to the combination of the other two categories. We will also show results using a continuous score as described at the end of section 5.2 (Ofsted overall score).

5.4 Is eligibility randomly assigned?

As is standard in RDD analyses, we check that date of birth in proximity of the cutoff is as good as randomly assigned. We start by plotting the distribution of our running variable (date of birth) either side of the two cutoff dates (31st December and 31st March) to investigate whether the policy determining entitlement to free part-time early education had any effect on the day on which a child was born. Parents who are aware of the importance of the eligibility rule (because they are well-informed or because they have an older child) might time the birth of their child to receive more free part-time childcare. If so, we would see relatively more births in the days preceding the cutoff dates, and fewer births in the first few days afterwards. As noted in Section 4 this could invalidate the identification strategy as date of birth would be correlated with outcomes for reasons other than eligibility.

The first panel of Fig. 1 plots the relationship between date of birth and number of children born on each day for the 8 weeks around the December cutoff. The bold line shows the raw number of births on each day. While there is no apparent bunching of births before the cutoff we do see some non-random patterns. In particular there is a clear weekly pattern in the number of births with fewer occurring at weekends, and a sharp drop at Christmas. These patterns are likely to be driven primarily by the timing of planned caesarean sections and inductions away from weekends and holidays. We therefore plot residuals from a regression of the number of births on separate sets of dummies for being born on each day of the week, bank holidays and festivities (e.g. Christmas), and their interactions. The pattern of births is now much smoother over time with no relationship between the number of births and the cutoff. The same is true for the March eligibility cutoff shown in the second panel, where the smoothed line includes controls for Easter. In the remainder of the analysis we join the data for the two cutoffs and show how our results change without and with controls for the day of the week, bank holiday and festivities.

Distribution of births around the cutoff. Source: National Pupil Database and Early Year Census. Notes: Each point represents the total number of children born before or after the relevant cut off (31st December and 31st March). The line with a circular marker represents the unadjusted total number of births, the line with a cross marker represents the residual (plus overall mean) of a regression of number of births on separate dummies for days of the week, bank holidays, and festivities (e.g. Christmas), as well as interactions between days of the week and bank holidays and between days of the week and festivities

A second important check is whether observed individual characteristics are correlated with eligibility status. If births around the cutoff are randomly assigned, this should not be the case. We run regressions testing for the presence of a discontinuity in observable characteristics either side of the cutoff, using a specification similar to the one in Eq. (2), but where Xi is the dependent variable and among the vector of controls we have only day of the week, bank holiday and festivity dummies and their interactions. We vary the way we control for date of birth, using different functional forms and show results including and excluding average setting-level characteristics. Results (shown in Table 11 in the Appendix) are reassuring, as any effects of eligibility are very small and significant only at the 10% level.

6 Eligibility rules and childcare participation

In this section we provide evidence about the extent to which eligibility for the free entitlement leads parents to take up early education. We can only expect eligibility to affect educational outcomes if it leads to changes in behaviours. We use the Family Resources Survey which is an annual cross-sectional survey of UK households with interviews running continuously throughout the year.Footnote 22 We use data from the 2005–06 to 2012–13 cross-sections and select children living in England. In the Family Resources Survey we can observe participation in early education at different points in time between birth and entry into school, and how nursery attendance varies by the rules governing eligibility, i.e. by time of birth. We observe the date of interview and the month of birth of the child, so that we can only define the child’s age in months (rather than days). The fact that we do not know the child’s precise date of birth and we have a much smaller sample size means we cannot use the same RD design we adopt for our main analysis, and instead rely on a difference-in-difference approach.

As shown in Eq. (5), we model children’s participation in ECEC (defined by the parent reporting they are cared for in a day nursery or pre-school in the reference week) as a function of their term of birth (autumn, spring or summer, denoted by TOBi) and their eligibility (Tit), where the latter is defined by the age of the child at interview (eligibility takes value 1 if the child is observed after becoming eligible for the free entitlement and 0 otherwise). We then construct interactions between term of birth and eligibility. The coefficient on these interactions (γ) represents the impact of the free entitlement on participation for each group of children - as defined by their term of birth – when they are old enough to benefit. It gives the impact on attendance in all terms after eligibility. Our regressions also control for date of interview (month and year) and some family characteristics, see notes in Table 1. As in our main analysis, it is important that we control for a flexible function of age at interview (f(ait)), as children will be more likely to attend ECEC as they become older, independently of their eligibility status. This means that if we use a very short window of data (say children between 30 and 40 months of age) our eligibility variable might simply capture the effect of age at interview. In order to disentangle the effect of eligibility from the effect of age, we include in our regression children from a wide age spectrum (from 12 to 59 months) and control for a flexible function of the child’s age in months. Our basic results explore the difference made by changing both these margins, so we use samples of children observed at variable age-intervals between 12 and 59 months, and control for age in both a quadratic and cubic function for each sample.

Table 1 shows our main results. Eligibility for the free entitlement increases the use of childcare by 11 to 17 percentage points for the spring-born, 10 to 18 percentage points for the summer-born, and 10 to 16 percentage points for the autumn-born (these coefficients are not statistically different from each other). Our specifications also include a dummy for the term before a child becomes eligible to capture anticipation effects. It is possible that families are prepared to enter their child into an early education setting a few months before the child becomes eligible, perhaps in order to take advantage of available spaces. We expect this effect to be larger for children born in the Autumn term who become eligible in January but might anticipate this by attending in the September of the year before, at the start of the academic year. Indeed, we find that Autumn-born children experience an increase of about 6–11 percentage points in ECEC attendance the term before eligibility. This implies that the treatment effect for these children may be as much as two terms of additional early education and care.

These data also allow us to investigate the counterfactual childcare experience that is being displaced by eligibility for publicly funded childcare. Although sample size is not large, our results imply that children are switching from informal care into subsidisable ECEC. We show that time spent in informal care fell by 2 h when children become eligible and time spent in subsdisable care rose by a similar amount. We also find that the effects of the policy on participation are slightly larger for lower income families and less educated mothers, a result that is consistent with the evidence from Blanden et al. (2016) on impacts as the policy rolled out. Therefore, we might expect a stronger ITT effect for less advantaged groups.

7 Regression discontinuity results

7.1 The impact of an additional term of eligibility

As a first piece of descriptive evidence about the impact of eligibility for an extra term of ECEC on educational attainment at age 5, Fig. 2 plots measures derived from Foundation Stage Profile (FSP) scores either side of the eligibility cutoff (note that we pool the December and March cutoffs), adjusted for day of the week, bank holiday, and festivity effects and for average differences across schools (this is particularly important as assessments are conducted by teachers). For each outcome we plot the average value of the residual outcome measure (solid dots) for all children by day of birth and interpolate these points, allowing the slopes of the lines to be different before and after the cutoff.

Effect of eligibility on Foundation Stage Outcomes. Source: National Pupil Database and Early Year Census. Notes: Each point represents (for all children born on a specific day before or after the cut-off) the average value of the residuals from a regression of the outcome of interest on a dummy for being part of the March subsample, separate dummies for days of the week, bank holidays, and festivities (e.g. Christmas), as well as interactions between days of the week and bank holidays and between days of the week and festivities, and school fixed effects. The vertical line represents the pooled cut off (December 31st and March 31st). Also shown are the interpolated regressions lines connecting these points; the slope of these lines is allowed to change before and after the cut off

The Figure shows that a linear association between date of birth and outcomes matches the data well in this small window around the cutoff, although we will check for non-linearities in our regression analyses. Discontinuities at the cutoff are visible for the total FSP score, the categorical variable which measures whether children are working at or above the expected level overall, and (most clearly) the categorical variable which measures whether children are working at or above the expected level in literacy. These effects appear to be small, however.

In our regression analysis we run five specifications of our main model for each outcome. First we build up the set of controls. All models include school fixed effects, individual Xs, the number of children in the nursery attended the year before starting school, and control for a linear function of age. We then add controls for being born on each week day, a bank holiday or a festive day and their interaction (Eq. (2)). Last, we include the mean characteristics of the other children in the setting (Eq. (3)). We then check the sensitivity of the results to controlling for more flexible functions of date of birth using a quadratic term and a linear term which is allowed to change at the cutoff point. Level differences in outcomes between children born around the 31st of December and children born around the 31st March are captured by a dummy in all models.Footnote 23

The results for the outcomes in Fig. 2 are shown in Table 2. Estimation is by linear regression for continuous variables (such as the FSP standardised score), while for the categorical variables we run linear probability models. Standard errors are clustered by date of birth and school.Footnote 24 As we can see, the estimates are slightly sensitive to the controls included, but not at all sensitive to the functional form used to control for age. Evidence from the range of specifications shown indicates small but significant positive effects of eligibility on the probability that children are working at or above the expected level overall and at or above the expected level in literacy. The effects on literacy are slightly stronger. Eligibility for an extra term of free childcare raises the probability of achieving the expected level in literacy by just under 1 percentage point. Table 3 runs the same specifications for other FSP outcomes and confirms the positive and (weakly) statistically significant result for literacy using a continuous measure. Positive and slightly larger effects are also found for the creative development scale.Footnote 25,Footnote 26

Figure 3 shows the sensitivity of our estimates to varying the data window around the cutoff. Our sample includes children born 4 weeks either side of December 31st and March 31st, and we show in this figure how the point estimates (bold line) and confidence intervals (lighter line) vary when using data from 1 to 4 weeks, adding one day at a time. The figure shows that the estimate for the impact of eligibility on achieving the expected level in the overall FSP or the expected level in literacy vary quite substantially when using data on children born only a few days after the cutoff. These estimates are also generally larger and the confidence intervals are wider. This suggests that it would be very hard to be precise about the effect of eligibility by using a very short data window around the cutoff due to the difficulty of disentangling age and eligibility effects with very few data points. The Figure, however, shows that the estimates become much more stable and robust when using at least 2 weeks of data, and do not change much at all after 3 weeks.

Estimates by size of the data window around the cutoff. Source: National Pupil Database and Early Year Census. Notes: The dark line with a circular marker represents point estimates of the effect of being entitled to an extra term of free part-time education and care on the outcome of interest when considering a different number of days around the cut-off. The lighter lines represent the confidence intervals (CI) associated with each point estimate. The specification of the regression model is the same as shown in column (3) of Table 1, i.e. it includes a linear function of day of birth. The vertical lines indicate the point estimates obtained using one, two, three and four weeks of data around the cut off, respectively

Estimates for outcomes at age 7 find no statistically significant effects (results available on request). This is in line with much of the literature (Deming 2009; Elango et al. 2016; Garces et al. 2002; Schweinhart et al. 2005) which finds a rapid fade-out of early years’ interventions. Two possible caveats are in order here. First, the assessments provided at the end of the Reception year, the FSP scores, take into account a broad range of skills, including creative thinking and social and emotional development. By contrast, the assessments at age 7, the KS1 scores, are more narrowly focused on the academic subjects Mathematics, English and Science. Second, a recent literature argues that the effects of early interventions develop over time and may become clearer towards the adult years, so an insignificant result at age 7 (i.e. 3–4 years after the treatment) may not tell us much about the long-term effects (Elango et al. 2016).

The parameters we report in our tables are all intention-to-treat effects. The results from the previous section allow us to make a back-of-the-envelope calculation of the treatment effect on the treated. To do so we must assume that the increased probability of attendance when eligible in the FRS is the same as the share of eligible children attending in the first term of eligibility who would not attend otherwise. This rough calculation suggests that attending ECEC for an additional term (and therefore starting pre-school younger) as a consequence of the policy leads to around a 3.4–6.2 percentage point increase in the probability of working at or above the expected level for the overall FSP score (compared to a mean of 60%), and between a 5.1 and 9.3 percentage point increase in the probability of meeting the expected level in literacy (compared to a mean of 68%).Footnote 27

To put this effect in some context, we look at Cornelissen and Dustmann (2019). They estimate that each month of full-time education at age 4 has an effect on FSP scores at age 5 in the order of 6–9 percent of a standard deviation. Assuming linearity, this suggests an effect of 20–30 percent of a standard deviation for a term (roughly equivalent to 3.5 months). Our results in Table 2 show that our treatment has an estimated effect of 0.008 on total FSP, which would translate into an effect between 4.5 and 8.2 percent of a standard deviation after considering the impact of eligibility on attendance. The difference in results could be explained in several ways; because the children are different ages, the benefits of part-time attendance are not the same as those of full-time attendance, or alternatively the quality of ECEC is not comparable to the quality of compulsory education. This should not be surprising, given the pay and status differential between staff in nurseries and those in schools (Gambaro et al. 2014; Bonetti 2019).

Table 4 shows heterogeneity results for one of our outcomes, working at or above the expected level in the FSP. We add interactions with the child characteristics available in the NPD (gender, free school meals eligibility, deprivation of the neighbourhood in tertiles, language spoken at home, and ethnicity). There are striking results for gender: the benefits of attending an additional term are entirely experienced by boys (the interaction effect) with no significant effects for girls (the main effect). This is in contrast to evidence from early targeted interventions that finds larger effects for girls (Elango et al. 2016; Garcia et al. 2018; Havnes and Mogstad 2011) but consistent with newer evidence for universal programmes (Blanden et al. 2016; Cornelissen and Dustmann 2019; Cornelissen et al. 2018; Leuven et al. 2010).Footnote 28 Also, there is no evidence that an additional term spent in childcare is more beneficial for children from disadvantaged backgrounds as measured by free lunch eligibility and deprivation in the neighbourhood of residence (results in Blanden et al. 2016, indicate that effects of the policy roll out are slightly larger for disadvantaged families, but not statistically different).

The results in Table 4 are also relevant to our strategy to assess the effect of quality. As previously noted, if the effect of eligibility varied by social background we might confound this with variations in effects of eligibility by setting quality, casting doubt on the causal interpretation of the results that follow. There is limited evidence that this is the case, which is reassuring.

7.2 Does attending a nursery of higher quality have larger benefits?

We now turn to the second question addressed in this paper, that is whether there is a significant interaction between eligibility for an additional term in early pre-school education and the quality of the setting attended. Our regression models follow Eq. (4). We start by looking at staff qualifications, which can be considered measures of structural quality, and focus initially on working at or above the expected level in the overall FSP score as the main outcome of interest, although we will also show results for other outcomes in the Appendix.

First, we look at the share of graduates working with 3- and 4-year-olds within a setting. This includes Qualified Teachers and Early Years Professionals and continues to be cited in policy circles as a key quality criterion (Nursery World 2018; Department for Education 2017). Note that when adding this variable to our model we must control for the number of 3- and 4-year-olds per teaching staff (group size) to isolate the effect of qualifications, because regulations permit lower staff-child ratios when there is more highly qualified staff.

Table 5 shows our baseline results in column (1). Column (2) adds the share of graduates to the estimation. There is a positive association between the share of graduates and children working at or above the expected level in the FSP, but this is not statistically different from zero. To evaluate whether the share of graduates has an impact on the benefit of an extra term in childcare we interact this variable with our indicator for eligibility. If the assumption that sorting into settings of different quality is controlled for holds, this interaction would give the causal effect of spending the additional term in early education in a setting with a higher share of graduate staff. That is, it measures whether the quality of the setting increases (or reduces) the overall benefit of the extra term. Results from the interaction are displayed in column (3) and show a negative point estimate which is not statistically different from zero, suggesting that there is no additional benefit of being entitled to an extra term of part-time early education in a setting with a higher proportion of graduate staff.

In Section 3 we explained that the group of graduates is quite diverse, with qualified teachers (QTS) benefiting from much longer training than Early Years Professionals (EYP), who can obtain their qualification in as little as four months. We therefore look separately at these groups. Column (4) shows that there is a positive and statistically significant association between the share of QTS in a setting and our outcome, but this is not so for the share of EYP. To investigate whether there is an effect of entitlement to an extra term in nurseries with higher shares of QTS and EYP, respectively, we again enter interactions with eligibility in our estimation. Column (5), shows no effect of either QTS or EYP interactions on working at or above the expected level in the overall FSP. We check whether results are different if we use a binary indicator for whether any member of staff working with 3- and 4-year-olds has that qualification instead of shares of staff with a certain qualification. Results in column (6) again reveal no benefit of the extra term being spent in nurseries with higher quality in terms of staff qualifications. We also check for impacts on other outcomes, including the standardised total FSP score and the threshold measures used earlier and find that higher staff qualifications do not have an effect on the benefit from being eligible for an additional term of childcare on any of these outcomes.

Next we turn to the effect of setting quality as measured by the rating awarded by the national regulator Ofsted. As before, we first investigate the association between Ofsted rating and children working at or above the expected FSP level at age 5. Table 6 shows this in column (2), whereas column (1) reports our baseline finding. The coefficients on the indicators for Outstanding and Good ratings show that there is a positive and statistically significant association between ratings and child outcomes, where Satisfactory and Inadequate are the combined omitted category. Adding an interaction between Ofsted rating and eligibility in column (3) shows that those children who attend Outstanding settings have an additional benefit from eligibility to an extra term; it increases their probability of working at the expected FSP levels by 1.3 percentage points (2.3% of the mean) compared to children in lower quality settings. This effect is 2–3 times larger than the baseline effect of the extra term (0.005 in this column) and, if we are prepared to assume that any observed and unobserved selection into settings of a different quality is taken into account by the average characteristics of children in the setting, \(\overline {X_{j}}\), and the association between Ofsted rating and outcomes, Qj, then this effect gives us a causal estimate of how the eligibility effect varies with the quality of pre-school education. The sum of the coefficients on eligibility and its interaction with quality (that is, coefficients β and ϕ in equation (4)) gives the total effect of receiving the extra term in a setting of a particular quality. This effect is 1.8 percentage points in settings rated Outstanding, that is a 3% increase from the mean across all children in private settings, 3–4 times as large as the baseline effect of eligibility. In contrast to Outstanding nurseries, there is no additional effect of being eligible to attend nurseries rated Good for an extra term.Footnote 29

We repeat the analysis for another way of measuring Ofsted ratings, using the continuous measure which adds up scores on the six sub-areas (see Section 5). Columns (4) and (5) of Table 6 confirm that children attending a setting with a better rating do better, and there is (weak) evidence that spending more time in a better setting is beneficial. Exploring results for other FSP outcomes reveals that the interaction effect between quality (Outstanding) and eligibility is also statistically significant for high level attainment (working beyond the level expected in the FSP), but not for the other measures considered.

Our findings in Table 4 showed that all impacts of eligibility are found for boys. We might therefore suspect that the impact of being eligible for an extra term in an Outstanding nursery might also be restricted to boys. To investigate this we include in our model triple interactions between gender of the child, quality and eligibility. This obviously reduces the number of observations per cell which are used for the identification of the effects, so we expect some loss of precision. Results in Table 12 in the Appendix show that the magnitude of the effect of being entitled to an extra term of part-time early education in an Outstanding setting is larger for boys than for girls, with a coefficient of 0.016 and 0.02 for achieving a score at or above the expected level for the overall FSP and for literacy, respectively. While these coefficients are not statistically significantly different from zero, they are by far the largest effects observed in any of our models and point out once again that the gains of an extra term are not gender-neutral.Footnote 30

7.3 Robustness and sensitivity checks

In this section we present robustness checks and check the sensitivity of our results to sample restrictions. We focus on the main effects of the additional term (shown in Table 7, column (1)) We run two placebo tests where we use arbitrary cutoff dates to define eligibility status to check whether our results are unique to eligibility cutoff dates, and cannot be found at other arbitrary dates. This is shown in column (2) of Table 7, where we have set the cutoff to January 15th and March 15th, and use observations on children born 3 weeks around these dates. The second in column (3) uses 1 week either side of 21st January and 21st March. The point estimate for all FSP outcomes is now extremely close to zero for both placebos This indicates that the cutoff associated with eligibility has explanatory power for educational outcomes that is not shared by other, arbitrary, dates.

However, to be able to attribute the effect we observe to the entitlement at age 3 we need to make sure it is not confounded by school starting dates. As explained previously, term of birth also affects some children’s date of entry into compulsory schooling. We exclude from our main sample all schools where a significant minority of children start school in January or April, i.e. schools which appear to have different starting dates for children with different dates of birth.Footnote 31 Although starting date policies vary at the level of school and not district, in column (4) we more conservatively exclude all local authorities (or school districts) where a significant proportion of children (10%) start school during different terms over the year. This leads us to exclude a further 9.1% of observations from our sample. Our results are robust to this restriction and—if anything—the point estimates become larger.

Next we check whether our results could be contaminated by another policy implemented at the same time. During the period analysed here, the government introduced a new subsidy for the poorest 2-year-olds in some pilot areas of the country (Smith et al. 2009). This intervention was also made available in the term after the child’s birthday, so positive effects might be confounding the impact of the 3-year-old entitlement. To check for this we introduce in our regression a variable indicating the amount spent by each district on the 2-year-old subsidy, normalized by the number of children in the district to control for the effect of the pilot for 2-year-olds.Footnote 32 Column (5) of Table 7 shows that this makes little to no difference to our estimates.

The remaining two columns of Table 7 restrict the estimation sample in two ways. Column (6) presents estimates of the interaction between eligibility and setting quality when excluding the last cohort of children from our sample who were exposed to a slightly higher number of hours of free early education (15 as opposed to 12.5) and more flexibility for parents when to take these hours (e.g. could choose to have them all in 2 days rather than spread them over the week). Coefficients are very similar to those shown in the main results, albeit a bit less precisely estimated. Column (7) excludes London from our analysis as educational attainment has followed a different trend from that seen in other parts of the country in the last decade (Blanden et al. 2015). Effects are not driven by London.

8 Conclusion

This study moves beyond standard evaluations of universal ECEC programmes by providing evidence on the impact of marginal changes in the length and starting age of pre-school programmes on children’s educational outcomes and the effect of spending extra months in settings of differing quality. Both of these margins are important as countries with established universal ECEC programmes seek to optimise their impact on child development. Our results show very small benefits of being eligible for an additional term of free ECEC, even when scaled up by the likely relationship between eligibility and attendance. This implies that additional extensions of the current ECEC programme would not have noticeable effects on children’s development. Effects are concentrated on boys, but are not larger for disadvantaged groups.

One reason for the small impact of an extra term on children’s outcomes compared to those for marginal increases in time spent in English primary schools (Cornelissen and Dustmann 2019) could be that the extra term comes with an earlier pre-school starting age which has been shown in some studies to have a negative effect on children’s development. Another reason could be that the quality of the childcare provided was not good enough to produce the substantial benefits seen from other programmes (Fitzpatrick 2008; Havnes and Mogstad 2011), as hypothesised by Blanden et al. (2016). It is tempting to hypothesise that the smaller results are a consequence of lower resourcing, qualification levels and poorer pay of the average private sector nursery compared to primary school. We assess this possibility in the second part of the paper by examining if nurseries with higher observable quality characteristics produce larger gains from marginal increases in attendance.

Assuming that we have entirely controlled for sorting by child ability into settings with different characteristics, our results do not support the idea that extra time spent in nurseries would be more productive if all children had access to a teacher qualified to graduate level, in counterpoint to much of the policy discussion about quality. Of course, this is not to say that there is no change in the way that nursery workers are trained and recruited that would make a difference; we are only able to make comparisons within the current system. In contrast, we find that spending more time in a setting rated highly by the national regulator Ofsted improves children’s chances of achieving both expected and higher levels of attainment. This is somewhat surprising as previous correlational evidence on the effectiveness of both Ofsted and the US QRIS quality ratings has not been encouraging. Effects are around three times larger than the baseline in Outstanding settings, and roughly two thirds the size of those in Cornelissen and Dustmann (2019), implying that higher quality in this dimension would help to make pre-school more effective. While it is the case that we cannot find effects at age 7, this may be because our age 7 outcomes are more limited in what they measure. Also, other papers find that short-term fade-out can be observed even when there are long-term effects (Elango et al. 2016).

Our findings confirm that extending early education has the potential to improve children’s outcomes if it is of high enough quality. However, they also demonstrate that attempts to improve quality require nuance; raising staff qualifications is not sufficient. Our results could perhaps be interpreted to imply that in the pre-school context staff quality matters as it is recognised within the school inspection regime, but that staff qualifications do not proxy this adequately. These findings resonate with the literature on school quality which emphasises that teacher practice matters but finds it difficult to demonstrate the observable characteristics of teachers that lead to better student outcomes. As the Ofsted inspection grades are rather a black box, we are not able to pinpoint the specific practices which lead to enhanced child development, however our evidence illustrates that further consideration of the features of Ofsted Outstanding nurseries would be beneficial. Our results imply that, with careful consideration, countries should be able to provide regulation and inspection regimes which support the high quality provision that children need to flourish.

Change history

14 June 2021

The correct family name should be Del Bono and not Bono.

Notes

The results in Cornelissen and Dustmann (2019) indicate that outcomes at age 5 improve by 20–30% of a standard deviation for a 3.5-month treatment. It is important to note that Cornelissen and Dustmann study a shift from part-time ECEC to full time school, so the change in hours is similar to our setting. However, their effect is a treatment-on-the-treated effect whereas we estimate an intention-to-treat parameter in this paper. We will show, since eligibility induced a shift in childcare use by about 10–15 percentage points, our anticipated effect of 1–3 percentage points would still be detectable given our large sample size.

Positive effects are found in Gormley and Gayer (2005) and Fitzpatrick (2008) for the USA and in Havnes and Mogstad (2011) for Norway. However, Herbst and Tekin (2010) and Baker et al. (2008, 2019 find negative effects of the introduction of subsidised universal childcare in Quebec and of subsidies for childcare provided to working mothers in the USA, respectively, with particularly strong negative effects found for aspects of social and emotional development. Datta Gupta and Simonsen (2010) find no effects of ECEC enrolment on outcomes at age 7 in Denmark.

Similar policies are in place in the other nations of the UK, but we only have administrative data for England.

For example, the Tickell Review for the UK (Department for Education 2011) states “an ambition for the sector to become fully graduate-led” (p. 42).

Researchers use detailed controls or matching models to account for systematic differences between children whose parents choose to enrol them early and others. Arteaga et al. (2014), Shah et al. (2017), and Wen et al. (2012) all indicate that 2 years of Pre-K or Headstart in the USA is more effective than 1, across a range of outcomes. Mostafa and Green (2012) find that children who participate in 2 years of pre-school do better in PISA tests at age 15. Of particular relevance to our context is the Effective Provision of Preschool Education (EPPE) study which followed a sample of English children from their nursery experience in the late 1990s through to the end of compulsory schooling. Sylva et al. (2006) find that an earlier start at nursery improved progress up to age 7 but not beyond this.

The National Academy of Sciences Committee on Early Childhood Pedagogy advised that “Each group of children in an early childhood education and care program, should be assigned a teacher who has a bachelor’s degree with specialised education related to early childhood” (National Research Council 2001, p. 13).

The vast majority of US states have adopted the voluntary QRIS in an effort to improve the information available to parents and drive up the quality of ECEC. (Elicker et al. 2011 indicate that parents act on the QRIS, at least in Indiana). Schemes differ between states but the idea is to award settings or wider programmes a grade or star-rating based on a number of measures of quality. Given that QRIS ratings incorporate somewhat arbitrary cutoffs for measures which have been shown to have little influence on children’s outcomes (such as group-size 20 or below) and vary widely in how they use observation-based quality measures, it is hardly surprising that studies have shown only fairly weak, if any, relationship between QRIS ratings and children’s outcomes (Zellman and Perlman 2008; Sabol et al. 2013).

The impact of the roll out of this policy on children’s educational outcomes was studied in Blanden et al. (2016). Estimated effects are small in the short-run. This is largely explained by the fact that few families changed their behaviour when the policy was implemented. Effects faded out quickly even among those groups who took up childcare as a result of the free entitlement.

This change will affect the last cohort in our sample and we investigate the impact of this in our sensitivity checks.

Working families are defined as two-parent families where both are working the equivalent to 16h a week at the National Living Wage (although they can work less if they earn more), and who both earn less than £100,000 each. A single parent will qualify if (s)he meets the working criteria applied to each dual parent (Department for Education 2015).

The autumn term runs from the beginning of September to the Christmas holidays, the spring term from early January to the Easter holidays, the summer term from after the Easter holidays to the summer break around the third week of July. Each term has a length of approximately 3.5 months which varies slightly according to the Easter dates.

Public sector nursery education was provided by some local authorities in decades prior to the introduction of the free entitlement. The expansion of free ECEC occurred almost entirely in the private (or Private, Voluntary and Independent, PVI) sector. See Blanden et al. (2016).