Abstract

We study the intergenerational effect of birth order on educational attainment using rich data from different European countries included in the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE). The survey allows us to link two or more generations in different countries. We use reduced-form models linking children’s education to parents’ education, controlling for a large number of characteristics measured at different points in time. We find that not only are parents who are themselves firstborns better educated, on average, but they also have more-educated children compared with laterborn parents (intergenerational effect). Results are stronger for mothers than for fathers, and for daughters than for sons. In terms of heterogeneous effects, we find that girls born to firstborn mothers have higher educational attainment than girls born to laterborn mothers. We do not find evidence for potential channels other than parental education that could explain the intergenerational effect of parental birth order.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Does being a firstborn child matter for outcomes later in life? The evidence we have to date shows that this is the case. The economic literature in particular shows that firstborn children tend to have better educational attainment than laterborn children in developed countries (Becker and Lewis 1973; Black et al. 2005a; De Haan 2010; Hotz and Pantano 2015; Monfardini and See 2016; Esposito et al. 2020), whereas the opposite is found for developing countries (De Haan and Plug 2014). Furthermore, recent research using rich survey or administrative data shows birth order effects on earnings (Bertoni and Brunello 2016), health outcomes (Black et al. 2016), non-cognitive skills and personality (Black et al. 2018), IQ and intelligence (Black et al. 2011), among other outcomes. Less has been done to explore whether these effects persist across generations. If a firstborn has higher educational attainment than laterborns, how much of this effect translates into higher educational attainment for his children? Answering this question empirically is not trivial. It is rare to have information on family structure for two or more linked generations along with information on completed education for all members of the family, family size, and other relevant variables. Data that allow examining other potential channels besides education, such as family income, behavior, health, and personality, are even more scarce.

In this paper, we try to fill this gap by studying the intergenerational effects of being firstborn on education. We exploit rich survey data from the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE), which allow us to link more than two generations in many European countries. We contribute to the literature in three ways. First, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that analyzes the persistence of birth order effects (more specifically, being a firstborn) on the next generation. Second, we provide cross-country evidence on the impact of birth order on both the first and second generations (parents and children) using the same empirical framework. In particular, the data allow us to overcome one of the main limitations when analyzing birth order effects, namely, being able to account for both family size and birth order of the two generations that we consider.Footnote 1 Third, we provide evidence on the main mechanisms at work besides parental education, such as fertility patterns, mortality, bequests, and risk aversion, through which parental birth order may affect children’s education. For instance, if for cultural reasons firstborn parents are more likely than laterborn parents to receive bequests, this might lead to a positive effect on children’s education.

We exploit the availability in SHARE of data on linked generations coupled with the rich retrospective information on early-life circumstances (SHARELIFE) from nationally representative samples of Europeans aged 50 or more in the following countries: Austria, Belgium, Czech Republic, Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, and Switzerland. The spouse or partner is also interviewed in SHARE, independently of her age, which allows us to have more detailed information within the family.

The SHARE survey presents several advantages for our analysis. First, combining SHARE and SHARELIFE data allows us to have detailed information on family structure (e.g., birth order and number of siblings) for SHARE respondents when they were 10 years old, as well as detailed information on their own family as adults (number of children, children’s birth order, etc.).

Second, SHARE respondents who have children (henceforth, “parents”) are asked to provide information on their offspring, including demographic characteristics (birth year, gender, whether they are biological children or not), their highest education attainment based on the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED) framework, at the time of the interview regardless of where their children live. This is an added value of our data, as most available studies that analyze intergenerational mobility usually observe only cohabiting children (Oreopoulos et al. 2006).Footnote 2

Third, since SHARE respondents (parents) are at least 50 years, most of their children have already completed their formal education. This is another advantage, as many available studies lack information on completed education for both parents and children and only consider outcomes like school dropout or grade repetition (Oreopoulos et al. 2006; Black and Devereux 2011).

Combining SHARE and SHARELIFE, we have a final sample of 38,000 dyads of parents and children. Our reduced-form models show that there are persistent birth order effects on educational attainment, both for an individual and for his/her children. More specifically, we find that firstborn parents have, on average, 0.343 more years of schooling than laterborn parents, controlling for family size and a large set of characteristics. When estimating separate regressions for mothers and fathers, we find the educational returns of being firstborn are about 0.244 years for the mother, and 0.397 for the father. These results are in line with the available literature, and more so with other papers that use the SHARE data.

In addition to these papers, we find that children who have a firstborn parent (either the mother or the father) have on average 0.148 more years of schooling than children of late-born parents. When we look at separate effects by the dyad mother-child and father-child, we see that the effect is strong and statistically significant only for mothers. Having a firstborn mother, all else being equal, is associated with an average increase of 0.154 years (about 2 months) of schooling for children. Interestingly, when looking at differential effects by gender, we see that this spillover effect is mostly passed from mother to daughters, whereas we do not find a significant effect of birth order transmission for sons.

In the paper closest to ours that uses data from SHARE for related but different purposes, Bertoni and Brunello (2016) study the effect of birth order on earnings using the sample of SHARE respondents from eleven countries. Differently from us, they only look at males and do not consider any intergenerational links. They find that firstborns enjoy a premium in terms of entry wages, but this advantage disappears about 10 years after labor market entry. Interestingly though, this advantage is explained in part by a positive effect on education, which may also play a role in shaping the education of later generations. This is the type of variation that we investigate in this paper.

The paper is organized as follows: Section 2 discusses the relevant literature and the main findings on the effects of birth order on education and other outcomes. Section 3 describes our data, namely, the variables used and sample selection, and provides some descriptive statistics. Sections 4 and 5 outline our empirical strategy, based on reduced-form regressions and the main results. In Section 6, we perform a series of robustness checks to our baseline specification, and try to test for other potential mechanisms that could explain the observed intergenerational effects of parental birth order on children’s education. Section 7 summarizes the main conclusions and discusses the policy implications.

2 Literature

The relationship between birth order and education has been explored by academics in different fields such as sociology, psychology, demography, and lately economics. We will mostly refer to the recent economic literature as we share the same methods and conceptual framework.

It is well established in the literature that earlier borns tend to have more years of education than laterborns (Becker and Lewis 1973; Behrman and Taubman 1986; Black et al. 2005a; De Haan 2010; Mechoulan and Wolff 2015; Monfardini and See 2016; Esposito et al. 2020).

However, most of the evidence on the relationship between birth order and education attainment come from single-country studies. Furthermore, to the best of our knowledge, there are no papers that document both the first and second generation effect of birth order on education relying on data from multiple countries.

Why are adult outcomes likely to be affected by birth order? Many potential explanations have been proposed across several academic disciplines. First, credit-constrained families may run out of financial resources to support investment in human capital of laterborn children, especially in larger families. This last consideration highlights the importance of appropriately accounting for family size in the birth order analysis, since laterborn individuals are more likely to belong to larger families (e.g., a birth order of 4 implies a family size larger than or equal to 4). On this, Pavan (2015) shows that firstborn children outperform their younger siblings on measures such as cognitive exams, wages, educational attainment, and employment. Differences in parents’ investments across siblings can account for more than one-half of the gap in cognitive skills among siblings. Second, there might exist cultural preferences that tend to favor investment of resources and time toward firstborn children or conversely on laterborn children. For instance, De Haan and Plug (2014) using data from Ecuador find that laterborns have higher education compared to earlier borns. They argue that high poverty rates in Ecuador or in developing countries more generally could be an explanation for this opposite finding. A recent paper by Esposito et al. (2020) using data from Mexico, a middle-income country but with an array of features typical of low-income countries, finds a negative correlation between birth order and education. They rely on Census data and their results shed light onto the existence of economic gradients in birth order effects when we compare results from different countries. Third, if the time spent with parents during early childhood is more valuable (in terms of future educational achievement) than the time spent when children are grown up, then a firstborn child is advantaged since she does not have to share parental time with other siblings until a second child is born. Price (2008) using data from the American Time Use Survey shows that a firstborn child receives on average 20 to 30 more minutes of quality time compared to a second-born child while controlling for family size and an extended number of observed characteristics. Fourth (but related to the third reason), as emphasized by Zajonc (1976) “confluence model,” the average intellectual environment within the family declines as the number of children increases. In other words, a first child is exposed to the richest intellectual environment composed of two cognitive mature adults, a second child lives with two adults and one immature child, and so on: the result is that laterborn children face the most diluted intellectual environment, with negative consequences for their education. Controlling for family size is relevant as shown by Booth and Kee (2009), who using data from the British Household Panel Survey build a new birth order index that tries to separate family size from birth order effects and find that the shares of family’s educational resources decrease with birth order. Finally, parental behavior might play a role. Hotz and Pantano (2015) suggest that there might be strategic parenting, according to which the upbringing of a firstborn child is stricter in order to deter bad behavior in laterborn children, and this strict upbringing contributes to firstborns’ higher education. Similarly, Jee-Yeon et al. (2016) document birth order differences in cognitive and non-cognitive outcomes and maternal behavior from birth to adolescence using data from the Children of the NLSY79, and find that broad shifts in parental behavior from first to laterborn children is a plausible explanation for the observed birth order differences in education and labor market outcomes.

Other channels have been explored such as the relationship between birth order and intelligence, as measured by IQ or by ad hoc designed cognitive tests. This literature is highly controversial. Most of this controversy boils down to whether birth order has genuine within-family effect (with earlier born being more intelligent then laterborn in the same family), or reflects spurious between-family association (with earlier born in small families being more intelligent than laterborn in large families). Black et al. (2011) find large and significant birth order effects on IQ for a sample of Norwegian young men, using both cross-sectional and within-family methods; however, the authors themselves state that such IQ gap cannot be ascribed to either genetic or biological differences resulting from different experiences in utero. Kanazawa (2012) studies the effect of birth order on a series of ad hoc designed cognitive tests for cohorts of British children, and, differently from Black et al. (2011), finds that the correlation between birth order and test scores is completely driven by the sibship size. Thus, the available literature provides more supporting arguments in considering parental birth order orthogonal to children’s innate ability, which is an important result for our study that explores the intergenerational spillovers.

There are also recent papers that use large population register data and exploit other mechanisms such as health and occupation. Brenøe and Molitor (2018) using Danish administrative data find that firstborn children are less healthy at birth, but this health disadvantage disappears by age 7, and becomes an advantage in adolescence. This finding is consistent with previous evidence of a firstborn advantage in education and with the hypothesis that postnatal investments differ between first- and laterborn children. Mechoulan and Wolff (2015) using data from France and estimating ordered models confirm the presence of a firstborn advantage in education and occupation, the latter persisting to a lesser extent after controlling for education. This translates into saying that the effects of birth order on health outcomes seem to be short-lived, and can hardly explain intergenerational effects of birth order on the education of offspring.

Furthermore, in a recent paper, Black et al. (2018) instead look at the relationship between birth order and personality traits. Using population population data on enlistment records and occupations for Sweden, the authors find that earlier born men are more emotionally stable, persistent, socially outgoing, willing to assume responsibility, and able to take initiative than laterborns. In addition, they also find that firstborn children are more likely to be managers, while laterborn children are more likely to be self-employed.

In the next sections, we first discuss the baseline specifications on birth order and education, and then look for other possible channels that could explain birth order effects (e.g., fertility choices, mortality selection, risk preferences).

3 Data and sample selection

3.1 The survey of health, ageing and retirement in Europe

Our study draws on the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE), a multidisciplinary cross-country household panel survey, which collects detailed information on individuals aged 50 or more (plus their spouses independent of age), who speak the official language of the country in which they reside and do not live abroad or in an institution. SHARE is to be considered a representative sample of old-age Europeans and is conducted in many countries, representing different areas of Europe. The data present different advantages for our analysis. First, SHARE collects detailed information at the household and individual level covering different areas of research such as household economics, education, health, social security and income, and financial investments. An advantage of the survey is the cross-country comparability of educational attainment and many other variables due to the common questionnaire and the standardization of fieldwork procedures in each country (Börsch-Süpan and Jürges 2005). Furthermore, it is designed to be harmonized with other surveys such as the Health and Retirement Study (HRS) in the USA and the English Longitudinal Survey on Ageing (ELSA) in the UK.

A second advantage of SHARE is the release of its third wave, named SHARELIFE, which recollects retrospectively information on life histories of each individual from age 10 onwards considering among others housing transitions (from first residence), employment transitions (from first job), complete fertility histories, and changes in health and health behavior, and includes also a distinct module with detailed questions regarding childhood circumstances (when respondents were about 10 years old). This is important in the light of numerous findings that early life circumstances matter for long-term outcomes (Almond and Currie 2011). In SHARELIFE, the modules of questions are arranged based on what is usually most important for the respondent and hence remembered most accurately (e.g., starting from children, partners, and then accommodation). Furthermore, the interview is supported by a multidimensional life grid, a computerized version of the life-calendar interview that allows respondents to view important events on a computer screen and at the same time allows the interviewer to link questions to parallel events. See Havari and Mazzonna (2015) for the analysis of recall bias problems in the SHARELIFE data, where they show that information related to the childhood period is very little affected by problems of recall bias.

In this paper, we use data from two waves of SHARE, waves 2 and 3, which cover the following countries: Austria, Belgium, Czech Republic, Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, Spain, Sweden, and Switzerland. The spouse or partner is also interviewed in SHARE, independently of her age, and this allows us to reconstruct families and analyze the effects of birth order for mothers and fathers.

To date, there are seven waves of SHARE available. From wave 4 to 7, new countries joined the SHARE project. Estonia, Hungary, Luxembourg, Portugal, Slovenia entered the survey between waves 4 and 6, whereas Lithuania, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Finland, Latvia, Malta, Romania, and Slovakia entered the survey in wave 7. Unfortunately, we could not use data from these new waves of SHARE for different reasons. First, from wave 4 to wave 6, it is not possible to reconstruct with a good precision families (dyads parent-child), as SHARE does not use anymore a unique child identifier. Second, from wave 4 onwards, SHARE respondents are asked to provide information on all children, whereas in wave 2 they are asked to provide information on up to four selected children. This complicates the analysis if we want to extend it to new waves of SHARE. Third, for the new countries in wave 7, only the SHARELIFE module has been conducted, and thus respondents (parents) do not report information on their children, as it is done in the other waves of SHARE (waves 1, 2, 4, 5, 6). Four, for the analysis, we need to use data on respondents that participate both in wave 2 of SHARE and in the retrospective survey SHARELIFE (wave 3) because information on children of respondents is asked in the former, whereas information on their family composition and other background characteristics are asked in the latter. Importantly, using data on respondents who participate in waves 2 and 3, which were conducted respectively in 2006/2007 and 2008/2009, reduces the incidence of attrition compared to wave 4 onward. Five, SHARE provides the materials to transform the level of education (ISCED) into years of schooling only for 13 European countries. This is crucial for our analysis, as we need to perform this transformation for the generation of children, for whom the survey records only the level of education (ISCED). For the aforementioned reasons, we can safely use data from respondents from 13 European countries who participate in both waves 2 and 3. This choice is motivated by the fact that important information on parents’ family background (e.g., birth order and family size) is collected by combining these two waves together.

3.2 Description of the variables

The main outcome variables in our analysis are the educational attainment of parents and children. We measure education by the number of years spent in full-time education. For parents, we have two measures for education attainment: self-reported years of schooling and the highest degree obtained based on the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED). They are highly correlated and hence using one or the other does not imply significant changes in the results. For children instead, we know the highest degree obtained (using ISCED classification), which we convert in years of education by exploiting information on the education system of each country.Footnote 3 The advantage of using the SHARE data is the cross-country comparability of years of education for both parents’ and children’s generations.

Information on parental birth order is gathered from wave 2. Each respondent is asked to provide his birth order, specifically whether he is the oldest child, the youngest one, or somewhere in between. Furthermore, he is asked to count the number of siblings still alive at the time of the interview. To better infer respondent’s number of siblings, we also rely on questions contained in the childhood module (SHARELIFE). In particular, knowing the number of persons living in the house at the age of 10 and the presence of each family component (mother, father, etc.), we compute the number of siblings at the age of 10. We combine information on number of siblings from both wave 2 and SHARELIFE, and in absence of information from wave 2 we use family size defined at the age of 10.Footnote 4 As for children’s generation, we also account for birth order and the family size as we do for parents. Information on children can be found in wave 2 in a specific module, where one of the parents (the family respondent) provides details for children’s year of birth, gender, education, whether she is a biological child or not, marital status, etc.

3.3 Sample selection

We select parents interviewed in both waves 2 and 3 of SHARE (about 17,767 parents). We also restrict the sample to biological children (97% of the sample), aged 25 or older who have completed their full-time education, ending up with a sample of 38,000 children (dyads parent-child). For each parent, we know the education level of their children (up to four children in wave 2 of SHARE) and we end up with a sample of about 38,000 children. Table 1 shows descriptive statistics for parents and children.

Children have on average 12.69 years of education, 49% are females and they are on average 40 years old at the time of the interview. About 44% of them are firstborns, and were born in families with an average number of children of 2.75.

4 Empirical analysis

The existing literature has mainly looked at the impact of birth order on education, earnings, fertility choices, etc. Our data offer the opportunity of assessing the birth order effects on different generations. Spillover effects are possible, as the literature that studies the intergenerational transmission of schooling identifies parental education as one of the key inputs of the so-called nurture channel.

Figures 1 and 2 provide descriptive evidence on the association between birth order of the parents and the educational attainments of parents and their children.

Distribution of years of schooling of parents and children by parental birth order. The top panel shows the cumulative distribution function of parental years of schooling (top left for the mother and top right for the father), by parental firstborn status. The bottom panel shows the cumulative distribution function of children’s years of schooling by parental firstborn status, considering separately the dyads mother-child and father-child

In particular, the top panel of Fig. 1 shows the distribution of mothers’ and fathers’ years of schooling by birth order (firstborn versus not firstborn). Parents who are firstborns have higher years of schooling than parents who are not firstborns. For example, the probability of low education (having 8 years of education or less) is 30 percentage points for mothers who are firstborn but increases by 10 percentage points for mothers who are not firstborns. For fathers, the difference is even higher (from 20 percentage points for firstborn parents to almost 40 percentage points for laterborn fathers). In the bottom panel of the same figure, we show the distribution of children’s schooling by the parental birth order, mother (left figure) and father (right figure). Children whose parents are firstborns have on average more schooling compared to children whose parents are not firstborns. In this case, the difference is not as strong as in the case of parents but it signals the presence of spillover effects.

In Fig. 2, we take one step forward and plot the average education of parents and their children by parental birth order, but controlling for family size.

In the top left figure, we see that the average years of education of firstborn mothers is always higher compared to laterborn mothers, independently from the family size. Overall, a firstborn mother has approximately 0.5 to 1 more years of education than a laterborn mother. A similar pattern is observed for fathers (top right figure). However, for females (mothers), we see that the difference in education attainment between firstborn and laterborn children gets closer to 0 for mothers born in larger families (with 4 children or more). We do not observe this pattern for males (fathers), and could be explained by the fact that for women it might be more difficult to reach a higher education level, if they are born in larger families.

The bottom left and bottom right figures show the results for the second generation. Children of firstborn parents have approximately 0.25 more years of education compared to children of laterborn parents: this advantage is again significant and stable at any level of family size. An interesting result emerges from this chart. Not only does birth order exert a strong influence on someone’s education but also it has predictive power for the educational attainment of the next generation. For the generation of the children, we see that there is a difference between children of firstborn mothers and children of laterborn mothers, and interestingly it remains constant with family size.Footnote 5

These figures are informative but do not allow us to account for additional background characteristics. For this, we rely on regression models.

We estimate two reduced-form models, one that captures the effect of parent birth order on his/her own education (first generation effect) and the other one that captures the effect of parental birth order on children’s education (second generation effect).

The baseline model for the relationship between the birth order of the parent and own education is:

whereas the baseline model for the relationship between birth order of the parent and children’s education is:

\(Y^{p}_{ij}\) denotes the years of schooling of the i th parent (either the mother or the father) of the j th child,Footnote 6\(Y^{c}_{ij}\) denotes the years of schooling of the j th child born to the i th parent. Fi is an indicator taking value 1 if the parent is a firstborn. Si captures the family size of parent, considering the information collected in wave 2 and wave 3 of SHARE (at the time of the interview, and when the parent was 10 years old). Xi is a vector containing other family background characteristics at the time the parent was about 10 years old, Zij is a vector of controls for the birth year and the country of residence of the parent (the reference country is Austria) and for the gender and birth year of the child, whereas 𝜖ij and ψij are the regression errors.

More specifically, Xi contains indicators for the breadwinner in the family (the grandparent of the child) being low-skilled, for the father of the parent (i.e., the grandfather of the child) being absent, and for the mother of the parent (i.e., the grandmother of the child) being absent, while the vector Zij includes an indicator for the child being a female, a set of indicators for the birth year of the parent and the child and parent country of residence at the time of the SHARE interview. The birth cohort and country fixed effects help in capturing time-invariant unobserved characteristics (risk aversion, rate of time preference, etc.). Moreover, controlling for both parent and child birth cohort fixed effects translates into accounting somehow for the age of the parent when the child is born. This is an important variable to account for, as there may be a risk of picking up differences due to maternal factors of first- and laterborn children born to the same cohort. As a robustness check, we instead explicitly control for mother’s age at birth when estimating model Eq. 2. Unfortunately, the same cannot be done when estimating the effect of birth order for the parents’ generation, as we do not have complete information on their own parents’ birth year. This information is reported only for respondents whose parents are still alive at the time of the interview.

We estimate model Eqs. 1 and 2 via ordinary least squares (OLS). We consider in our sample children who at the time of the interview were aged 25 or older. This is necessary in order to have linked generations, where both have completed the educational attainment. As explained earlier in the paper, this is a clear advantage, as we can also compare the results between the two generations.

Similarly to Bertoni and Brunello (2016), we are not able to use a family fixed effect model, as we do not observe multiple members of the family of origin of SHARE respondents (parents), namely the siblings of the parents. Therefore, we first estimate a pooled model, and as a robustness check we estimate separate regressions by family size. We already showed from the raw data in Fig. 2 that the estimates are stable when we account for family size. Furthermore, differently from Black et al. (2005b), we use survey data which are of a limited sample size. Using either model leads to comparable results, and it signals that pooling the data on families does not affect the estimates.

For the same reasons, we repeat this exercise when estimating the parental birth order effects on children’s education, as we are comparing children born to firstborn or laterborn parents. In an ideal experiment, we would be comparing cousins. Unfortunately, this is not possible with the data at hand.

5 Main results

We introduce the main results from the two empirical models described in Section 4. Table 2 shows the estimated effects for parent being firstborn on parents’ own education attainment, using the pooled sample of parents.

The coefficient on the dummy variable firstborn parent (FB parent) is positive and statistically significant at the 1% level in all the specifications. In column 1, we estimate a model that accounts for firstborn, family size, country, and birth year fixed effects. In column 2, we add to this model variables that account for parental family background when the parent was 10 years old which were collected in the SHARELIFE wave, namely a binary indicator if they lived in a house with bad accommodation features (e.g., absence of fixed bath, cold and hot running water supply, toilet inside, central heating), an indicator for whether they lived in a rural area, number of rooms per capita, an indicator if the main breadwinner had a low occupation at age 10,Footnote 7 and finally whether the mother, father, or grandparent was present in their home at the age of 10. In column 3, we add two indicators for parent ever experiencing hunger and financial hardship measured around age 10 as in Havari and Peracchi (2017, 2019), who study the long-term effects of exposure to WWII hardships.

We find that being a firstborn parent increases the education attainment by 0.343 years in column 1 to 0.321 years in column 3, with the full list of controls (about 4 months). The results are stable even if when we account for parent family size (number of siblings plus the respondent), where having an additional sibling reduces the educational attainment by 0.477 years in column 1 to 0.199 in column 3. As for the other covariates, considering the specification in column 3, we see that having lived in a house with bad accommodation features or in a rural area, as well as having the main breadwinner in low occupation, reduces the educational attainment for the parents respectively by 1.027 years, 0.929 years, and 0.586 years (between half and a year of schooling). Having lived in a house with a higher number of rooms per capita (rooms per capita hereafter) is associated with an increase of 1.390 years of education. Furthermore, we see that the presence of parents in the house (either mother or father) increases the educational attainment by a third of a year (0.362 and 0.347 years), whereas the presence of the grandparents does not seem to have an effect. As expected, having experienced hardship indicators such as hunger or financial hardship at the age of 10 is associated with a reduction in the number of years of schooling by half a year to a year (between 0.521 and 0.989 years). These results are in line with those found in Havari and Peracchi (2017, 2019), who show that exposure to hunger or financial constraints leads to a negative effect on education that persists across generations.

Interestingly, the magnitude of the birth order coefficient is in line with other papers that investigate the effect of birth order on education based on the SHARE data (Mazzonna 2013).

In addition, we also report separate regressions for the responding parent being either the mother or the father. Results are shown in Table 3 for each of the three different specifications discussed above (columns 1–3 for the mother and 4–6 for the father).

We can see that being a firstborn is associated with an increase in terms of years of schooling of about 0.244 years for the mother, and 0.397 for the fathers when using a large number of controls. The effect is stronger for the males (fathers), about twice as large than females, and the magnitude of the coefficient is comparable to what has been found by Bertoni and Brunello (2016), who study the effect of birth order on wages looking only at male respondents in SHARE. As for the other control variables related to family size and living conditions around the age of 10 (rural area, rooms per capita, bad accommodation), results are pretty much similar and in line with the findings in Table 2 where we looked at the pooled sample. However, we find that the presence of either the mother or the father at the age of 10 (these are the grandparents for the children’s generation) is associated with a higher number of years of schooling only for the mother (0.417 and 0.464 years respectively). Results are significant at the 5 and 1% levels. For fathers, we find that hunger at age of 10 and financial hardship at the same age is more detrimental for their education attainment.

In Table 4, we show the results of parental birth order spillover effect on children’s education (second generation effect) for the pooled sample, whereas in Table 5 we report the estimates separately for the dyads mother-children (columns 1–3), father-children (columns 4–6), and for the three different specifications.

From Table 4, we see that having a firstborn parent (e.g., FB parent) is associated with about 0.148 more years of schooling for the children when we only include few controls and 0.102 years of schooling with many controls. Next, we see from Table 5 that the coefficient of FB parent remains statistically different from 0 only for the mothers, when we add all the list of controls (in columns 3 and 6). This effect diminishes when we look at dyads father-children. Having a firstborn mother, all else being equal, is associated with an increase of 0.154 years of schooling for the children (about 2 months). In this specification, we include additional variables such as a dummy for the child being female, whether child is a firstborn, family size, and parent’s age at birth, besides the list of country and birth year fixed effects for both parents and children.Footnote 8

These results are coherent with what has been found in the literature so far: in the sense that mother’s education (which is one of the main channels through which birth order works) seems to matter most (Holmlund et al. 2011).

On this line, we extend our analysis by also looking at potential differential effects of parental birth order by child gender. Results are reported in Table 6, where on the top panel we show the estimates for the dyads mother-daughter and mother-son, whereas in the bottom panel for the dyads father-daughter and father-son.

For each combination, we estimate three different specifications as we have done so far. Interestingly, we find an effect only for the dyad mother-daughter, namely that having a firstborn mother is associated with an increase in daughter’s education of about 0.168 years (column 3), compared to those who have a laterborn mother, everything else being equal. The estimates are statistically significant at 10 and 5% levels, depending on the specification. Again, we do not find any significant effect for the father’s side. These results point toward an important role of birth order of the mother for children’s educational attainment.

6 Extensions

6.1 Robustness checks

We now discuss a series of robustness checks to the baseline specifications discussed in Section 5. First, as explained earlier in the paper, we are not able to use family fixed effect models, as we do not observe multiple members of the family of origin for the parents’ generation, namely siblings completed years of schooling. For this reason, we look at the pooled sample. As a robustness check, we run separate regressions for specific family size, following Black et al. (2018) and Bertoni and Brunello (2016). Of course, this implies to estimate the model for smaller samples, but a comparison is needed to check if the birth order effects vary when fixing parental family size.

Results for the pooled sample are reported in Table 7.

In the top panel, we show the results for parents’ years of schooling. Being a firstborn parent is associated with higher years of schooling and such effect monotonically declines with family size. However, the magnitude of the effect is comparable to the one obtained in Table 2. In the bottom panel, we report the estimates for children’s generation, separately for the dyad mother-children and father-children. In line with our baseline estimates, we find that (i) children of a firstborn mother—independently from the family size—complete about 0.2 years of schooling compared to children of laterborn mothers; (ii) the spillover effects for firstborn father’s in terms of children’s education attainment are not statistically significant.

Second, in the baseline model for the children, we include the firstborn dummy separately for each parent. As a robustness check, we estimate a joint model where we include both the birth order and family size of the mother and the father, and additional control variables. This model is estimated for a subsample of SHARE where both the respondent and spouse are interviewed.Footnote 9 The estimates are in line with the findings from the baseline model, namely that children of firstborn mothers have on average 0.188 additional years of schooling compared to children of laterborn mothers, whereas we do not find any statistically significant effect for firstborn fathers. The magnitude of the estimated coefficients is also in line with our baseline model.

Third, we re-estimate the model by excluding parents who are single children. The results are not affected by this choice. We find that being a firstborn parent increases own education attainment by 0.345 years, and children’s education by 0.120 years. The comparison with the baseline estimates holds even when we distinguish by parent and child gender.Footnote 10

Fourth, since we estimated a model with country fixed effects, it could be that results are driven by a specific country in the sample. Since we do not have a sufficiently large sample to estimate the model separately by country, we run the regressions leaving one country out at each time and results are comparable.Footnote 11

Finally, we also re-run our analysis using different samples of parent and children’s birth cohort. In the baseline analysis, we look at parents whose children are older than 25 years old at the time of the interview, to keep a larger sample size and to avoid truncating our data further. Results are robust even when we select parents and children that are not too old. In any case in all specifications, we account for birth year fixed effects for both parents and children, and this accounts for the issue of cohort selection.

All in all, we are confident that our estimates are robust to the specification used and to the sample choice.

6.2 Other channels

Birth order and fertility choices

As discussed in Section 2, different theories and mechanisms can explain the negative correlation between birth order and education attainment. Recent studies have tried to prove the existence of other potential mechanism such as fertility patterns.

A recent paper by Lin et al. (2020) studies the role of unwanted fertility in the observed birth order patterns. The authors rely on the longitudinal micro-data from the US Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID) survey which contains a specific module questioning respondents about their behavior during each pregnancy. They find that laterborn children are more likely to be unwanted, simply because it is likely that they were conceived when the family was not planning to have more children. The authors also find that being an unwanted child can lead to negative outcomes later in life, especially on education, as parents could disrupt their investments on unwanted children. This has implications for the laterborn children who are the more affected ones. Thanks to the richness of the data, the authors document that these birth order effects disappear if families can plan optimally and have proper control of their fertility behavior.

Differently from PSID, the SHARE survey does not include questions on perceptions or assessments of pregnancy history. However, we can check if there exists a relationship between parental birth order (being firstborn or not) and parental fertility, namely the probability to have a child and the total number of children. Results are reported in Table 8.

In columns 1–3, we show the results for the probability that a SHARE respondent has a child (we use the full sample of SHARE respondents that do or do not have kids), whereas in columns 4–6 we use as outcomes the number of conceived children. We report results separately by gender: columns 1 and 4 the pooled sample, columns 2 and 5 female respondents, and columns 3 and 6 male respondents. Our results do not point to any significant correlation between parent birth order and fertility preferences. We account for a large number of characteristics as we do in the baseline models, so with the data at hand we can exclude this existence of this channel as a prevailing one.

Birth order and mortality

Empirical studies that test the relationship between birth order and mortality lead to mixed results. Modin (2002) finds that laterborn children have greater mortality compared to laterborn children, whereas other studies do not find a clear pattern, nor significant results. More recently, Barclay and Kolk (2015) using Swedish population register data look into the relationship between individual birth order and mortality later in life.

In our analysis, we look at the effect of parental birth order on children’s educational attainment, so somehow we are interested in selective mortality of both generations. To test for the existence of this relationship, we rely on data from the Human Mortality Database (HMD)Footnote 12 which allows to construct long annual time-series death rates by age, gender, and country for 10 of the countries included in our sample of age and gender-specific death rates for 10 of the countries included in our sample. In order to check for the presence of birth order effects in mortality of two linked generations, and given that for younger cohorts of children we have shorter series, we look at mortality at birth.Footnote 13 We then merge this database by country, calendar year (corresponding to the birth year of parents and children), and gender for both generations. Results are reported in Table 9, where in the top panel we report the results for parents and in the bottom those for the children.

We do not observe any significant relationship between being a firstborn parent and mortality at birth for both cohorts.

Birth order and inheritance

Another plausible channel through which parental birth order could affect children’s education could be through their degree of wealth. For instance, there could be a relationship between birth order and inheritance. In SHARE, we do not have specific data on individual wealth, but only on household wealth at the time of the interview. However, we do have information on whether the SHARE respondents (parents) have received inheritances from their family.

In Table 10, we show estimates from a linear probability model where the outcome variable is a binary indicator which takes value 1 if the parents have ever received a house as bequest (top panel) or have bought/built it with some help from the family (middle panel).

For each outcome, we use two specifications: the full sample in columns 1 and 3 and CSL sample in columns 2 and 4. We notice that being a firstborn parent seems not to have a significant effect on the probability of inheriting a house or building it with some help from the family. Thus, this channel does not seem to matter for parent education.

Birth order and risk preferences

Another potential channel through which parental birth order may affect children education could be related to risk-taking behavior or other types of attitudes. A common discussion in the sociological literature is that laterborn children could make more risky choices compared to firstborn children, to make up for the disadvantage of being a laterborn. Although it is not possible to fully test such assumption, we provide some evidence on the relationship between parental birth order and risk aversion.Footnote 14 We use a subjective measure of risk aversion based on the following question asked to parents:Footnote 15 “Which of the following statements on the card comes closest to the amount of financial risk that you are willing to take when you save or make investments? i) Take substantial financial risks expecting to earn substantial returns; ii) Take above average financial risks expecting to earn above average returns; iii) Take average financial risks expecting to earn average returns; iv) Not willing to take any financial risks.” We create a binary indicator that takes value 1 if the parent is willing to take either substantial financial risks or above average financial risks and 0 otherwise. Results are reported in the bottom panel of Table 10.Footnote 16 Interestingly, birth order seems not to have an effect on risk preferences. The results are in line with most of the research on the topic. A recent paper by Lejarraga et al. (2019) uses a comprehensive approach to study the birth-order effects on risk taking. They draw data from the German Socio-Economic Panel, the Basel-Berlin Risk Study, and additional data sources allowing to measure behavioral traits. The authors find that all these data sources and different analytical methods point toward no birth order effect on risk-taking behavior.

Are firstborns so different from middle and laterborns?

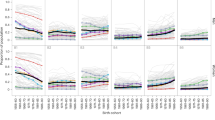

Due to data limitations, we cannot use the complete birth order of parents and clearly distinguish a firstborn from a second born, third born, and so on. If we expect firstborns to be special compared to laterborns (coherent with the idea of a role model), then we should also expect that second borns, third borns, and so on have similar education. This hypothesis cannot be tested using data for parents but we fill this gap using data for children, as we know precisely their birth order and family size. In Fig. 3, we show the residuals from a regression of children’s education on country fixed effects, birth year fixed effects, and the age of the parent (mother or father) at birth, separately by birth order and family size.

Children’s birth order and years of schooling. The figure shows residuals from a regression of children’s years of education on country fixed effects, cohort fixed effects, and parent’s age at birth, separately by birth order of the child (firstborn, second, third, fourth, or higher) and the family size of children’s generation (0 siblings, 1 sibling, 2 siblings, 3 siblings, 4 or more siblings)

The descriptive evidence rejects the hypothesis that firstborns are special. It is clear from the figure that educational attainment decreases monotonically with birth order, keeping a fixed family size.

7 Conclusion

While there is a large literature that looks at the effects of birth order on educational attainment, there are no available studies documenting the intergenerational effects of birth order on the education of the offspring. In this paper, we tried to fill this gap using rich data from the household cross-country Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe, which allows to reconstruct with a good precision the households and use rich information on parents’ socio-economic conditions when they were 10 years old. We consider linked parent-child observations for 13 European countries, with a final sample of 38,000 observations.

We find that children of firstborn parents have on average 0.148 more years of schooling compared to children of laterborn parents. This effect is strong and statistically significant, even when we account for a large set of characteristics. Interestingly, when we look at separate estimates for either the mother-child or father-child dyad, we find that this effect is mostly driven by the mothers. Firstborn mothers seem to have on average more-educated daughters, whereas no significant effect is found for sons.

Finally, we look at different potential channels that could explain these results, based on the economic and psychological literature and the available data. We do not find any birth order effect on fertility choices, mortality, and inheritance patterns, nor do we find an effect on risk-taking behavior. Our analysis points out to parental education as the main channel through which birth order effects persist until the next generation. However, richer data are needed, such as administrative data linked to survey data, to investigate further these empirical findings.

Notes

To some extent, we also account for the grandparents effect, using information when the survey respondent (parent) was about 10 years old.

Most surveys ask information about children only if they cohabit with the parents (e.g., the European Union Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC)), making it difficult to study intergenerational mobility for the overall population.

SHARE provides the table of conversion from ISCED level into years of education in the release guide attached to wave 2 (see SHARE release guide wave 2, version 2-5-0, released in 2011). This work has been performed by the SHARE team of experts for each participating country. This material is available in the SHARE webpage http://share-project.org/

Similarly to Black et al. (2005b), we treat parents without siblings as firstborns, in order not to introduce additional selection bias. However, results do not change if we exclude single-child parents. Furthermore, family size includes the number of siblings and the respondent himself/herself.

For sake of comparison, we control for the family size of the parent. The same figure can be replicated by accounting for the family size of the children.

Our notation reflects the fact that we may observe more than one child for a given parent, and more than one parent for a given child. We consider here the dyads parent-child, and not simply the sample of parents. This is done to compare results from Eqs. 1 and 2, namely the first and second generation effects of being firstborn.

We refer to the main breadwinner as the grandparent for the children generation.

In Tables 2 and 3, we do not include as covariates variables related to the children’s generation as we look only at the generation of the parents and these variables would be bad controls, in the sense that some of them could be considered as outcomes (e.g., number of children for instance). However, we have also estimated this model and the results do not change.

Since there is a considerable fraction of non-responding spouses/partners in SHARE, we preferred to use as the main specification the one considering separately the dyads mother-child and father-child.

Results are available upon request.

Results are available upon requests.

It is a joint project of the Department of Demography at the University of California Berkeley and the Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research.

We also run the regressions for mortality in later adulthood. However, in this case, we would look at mortality for different age groups between parents and children given that children are younger, so they cannot be directly compared.

Unfortunately, the SHARE data do not contain much information on attitudes and behavioral aspects.

This question is asked to the parent (SHARE respondent) who is the financial respondent in the household. If both parents are present in the household, they may decide to answer questions about their finances separately or choose one representative of the couple.

We also use an additional measure of risk-taking behavior, that is the binary indicator for parent being a smoker. Also in this case we do not find any meaningful relationship. Results are available upon request.

References

Almond D, Currie J (2011) Human capital development before age five. Handb Labor Econ 4:1315–1486

Barclay K, Kolk M (2015) Birth order and mortality: a population-based cohort study. Demography 52(2):613–639

Becker GS, Lewis HG (1973) On the interaction between the quantity and quality of children. J Polit Econ 81(2):S279–288

Behrman JR, Taubman P (1986) Birth order, schooling, and earnings. J Labour Econ 4(3):121–145

Bertoni M, Brunello G (2016) Later-borns don’t give up: the temporary effects of birth order on european earnings. Demography 53(2):449–470

Black SE, Devereux PJ (2011) Recent developments in intergenerational mobility. Handb Labor Econ 4:1487–1541

Black SE, Devereux PJ, Salvanes KG (2005a) The more the merrier? The effect of family size and birth order on children’s education. Q J Econ 120(2):669–700

Black SE, Devereux PJ, Salvanes KG (2005b) Why the apple doesn’t fall far: understanding intergenerational transmission of human capital. Am Econ Rev 95(1):437–449

Black SE, Devereux PJ, Salvanes KG (2011) Older and wiser? Birth order and iq of young men. CESifo Econ Stud 57(1):103–120

Black S, Devereux P, Salvanes K (2016) Healthy (?), wealthy, and wise: birth order and adult health. Econ Hum Biol 23:27–45

Black SE, Grönqvist E, Öckert B (2018) Born to lead? The effect of birth order on non-cognitive abilities. Rev Econ Stat 100(2):274–286

Booth AL, Kee HJ (2009) Birth order matters: the effect of family size and birth order on educational attainment. J Popul Econ 22(2):367–397

Börsch-Süpan A, Jürges H (2005) The survey of health, aging, and retirement in Europe. Methodology. Mannheim Research Institute for the Economics of Aging (MEA)

Brenøe AA, Molitor R (2018) Birth order and health of newborns. J Popul Econ 31(2):363–395

De Haan M (2010) Birth order, family size and educational attainment. Econ Educ Rev 29(4):576–588

De Haan M, Plug E (2014) Birth order and human capital development. Evidence from Ecuador. J Hum Resour 49:359–392

Esposito L, Kumar SM, Villaseñor A (2020) The importance of being earliest: birth order and educational outcomes along the socioeconomic ladder in Mexico. J Popul Econ 33:1069–1099

Havari E, Mazzonna F (2015) Can we trust older people’s statements on their childhood circumstances? Evidence from sharelife. Eur J Popul 31 (3):237–257

Havari E, Peracchi F (2017) Growing up in wartime: evidence from the era of two world wars. Econ Hum Biol 25(Issue C):9–32

Havari E, Peracchi F (2019) The intergenerational transmission of education: evidence from the world war ii cohorts in Europe. European Commission, JRC Working Papers in Economics and Finance

Holmlund H, Lindahl M, Plug E (2011) The causal effect of parents’ schooling on children’s schooling: a comparison of estimation methods. J Econ Lit 49(3):615–651

Hotz VJ, Pantano J (2015) Strategic parenting, birth order and school performance. J Popul Econ 28:911–936

Jee-Yeon K, Nuevo-Chiquero A, Vidal-Fernandez M (2016) The early origins of birth order differences in children’s outcomes and parental behavior. J Hum Resour 53:123–156

Kanazawa S (2012) Intelligence, birth order, and family size. Personal Social Psychol Bull 38(9):1157–1164

Lejarraga T, Frey R, Schnitzlein DD, Hertwig R (2019) No effect of birth order on adult risk taking. Proc Natl Acad Sci 116(13):6019–6024

Lin W, Pantano J, Sun S (2020) Birth order and unwanted fertility. J Popul Econ 33:413–440

Mazzonna F (2013) The effect of education on old age health and cognitive abilities-does the instrument matter? MEA at the Max-Planck Institute for Social Law and Social Policy

Mechoulan S, Wolff FC (2015) Intra-household allocation of family resources and birth order: evidence from France using siblings data. J Popul Econ 28(4):937–964

Modin B (2002) Birth order and mortality: a life-long follow-up of 14,200 boys and girls born in early 20th century Sweden. Social Sci Med 54(7):1051–1064

Monfardini C, See SG (2016) Birth order and child cognitive outcomes: an exploration of the parental time mechanism. Educ Econ 24(5):481–495

Oreopoulos P, Page ME, Stevens AH (2006) The intergenerational effects of compulsory schooling. J Labor Econ 24(4):729–760

Pavan R (2015) On the production of skills and the birth-order effect. J Hum Resour 51:669–726

Price J (2008) Parent-child quality time: does birth order matter? J Hum Resour 43(1):240–265

Zajonc RB (1976) Family configuration and intelligence: variations in scholastic aptitude scores parallel trends in family size and the spacing of children. Science 192(4236):227–236

Acknowledgments

We thank the editor, Shuaizhang Feng, and the two anonymous referees for the useful comments and suggestions. We also thank Erich Battistin, Massimiliano Bratti, Agar Brugiavini, Lorenzo Cappellari, Paul Devereux, Beatrice D’Hombres, Eric Gould, Claudia Olivetti, Mario Padula, Daniele Paserman, Paolo Pinotti, Erik Plug, Sylke Schnepf, Franco Peracchi, Paolo Paruolo, Enrico Rettore, and Daniela Vuri for helpful discussions and comments, as well as participants at Boston University, Bocconi University, University of Ca’ Foscari Venice, IRVAPP Institute Trento, University of Rome Tor Vergata, and at the conference meetings of the European Society for Population Economics (ESPE), the European Association for Labor Economists (EALE), and the Counterfactual Methods for Policy Impact Evaluation (COMPIE) 2016. This paper uses data from SHARE and SHARELIFE release 6.1, as of March 2017. The SHARE data has been primarily funded by the European Commission. See www.share-project.org for the full list of funding institutions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Responsible editor: Shuaizhang Feng

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Havari, E., Savegnago, M. The intergenerational effects of birth order on education. J Popul Econ 35, 349–377 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-020-00810-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-020-00810-5