Abstract

Based on Norwegian register data, we show that having a lone parent in the terminal stage of life affects the offspring’s labor market activity. The employment propensity declines by around 0.5–1 percentage point among sons and 4 percentage points among daughters during the years prior to the parent’s death, ceteris paribus. After the parent’s demise, employment picks up again and earnings rise for both sons and daughters. Reliance on sickness insurance and other social security transfers increases significantly during the terminal stages of the parent’s life. For sons, the claimant rate remains at a higher level long after the parent’s demise.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

This strategy admittedly raises another potential endogeneity problem, namely that the parents longevity may be causally affected by the offspring’s care.

It is also conceivable that the loss of—or the process of losing—a parent causes grief reactions, which in turn reduce the offspring’s ability to work.

Long-term care can also be provided by hospitals and thus recorded in national statistics as health care. Since the organization of services varies between countries, this implies that statistics from different countries may not always be directly comparable; see also Herolfson and Daatland (2001).

Informal and formal care alternatives are not necessary complete substitutes. Motel-Klingebiel et al. (2005) find in an international comparison that the welfare state does not crowd out family care, while Bonsang (2009) finds informal care to be a weak complement to nursing care. Finally, Jiménez-Martín and Vilaplana (2011) find that the question of complementarity or substitution varies among groups of users, and that formal care acts as a reinforcement of the family care in certain cases.

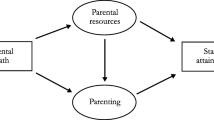

In the literature, utility is usually a household production function of consumed goods and leisure. In addition education is assumed to influence household production by changing the productivity of the inputs positively. By inserting the household production function in the utility function, utility can be expressed as in Eq. 1, see Fevang et al. (2008).

According to Norwegian legislation at least two thirds of the inheritance—up to 1 million NOK per child—must be shared equally between siblings. In addition, the progressivity of the inheritance tax system strongly favors equal sharing. To the extent that parents deviate from the equal-sharing norm, the motivation is typically to compensate for differences in needs, rather than to pay for help and services. Survey-based evidence reported by Halvorsen and Thoresen (2005) shows that only 1% of Norwegian parents with adult children think that intergenerational transfers should be disproportionately allocated to “the most helpful child”; 73% prefer equal sharing, while 23% prefer a division based on needs. These views also turn out to be reflected in actual gift behavior, i.e., there are no indications that children who help their parents a lot receive more gifts, compared to their siblings (Halvorsen and Thoresen 2005).

We treat the care provided by others as exogenous. Several papers have studied the interactions or strategic behavior of siblings when the parent’s health is considered a common good, see, e.g., Konrad et al. (2002), Engers and Stern (2002), Rainer and Siedler (2009) and Callegaro and Pasini (2007). There are also papers treating the publicly provided care as endogenous; see Van and Norton (2004).

Note that family identifiers are incomplete for individuals born before 1953, since the family tie is often missing for offspring who moved out of their parents’ home before the 1970 census. Since daughters of the relevant generations tended to move out significantly earlier than sons, this implies that we lose more daughters than sons in these birth cohorts. For individuals born before 1953, we can establish the identity of parents for around 57% of the men and for 40% of the women. Failure to identify parents also results from the fact that the parents are already dead in 1993, when we first can observe family linkages.

Employment is for each year defined as having earnings or self-employment income sufficiently high to earn pension points in the Public Pension System. Currently (2010/2011) the required income level is 75,641 NOK. We define people as social security claimants in a particular month if they receive benefits at the end of the month.

There are some social programs in Norway targeted at taking care of parents. In the time period analyzed, workers were entitled to up to 20 days of unpaid leave during the terminal phase of a parent’s life. If parents receive the terminal care at home, it is also possible to apply for paid leave. Very few persons have been granted paid leave to take care of adult family members, however. For example, in 2006 only 276 Norwegians received such payment.

Let y ei (g,a,t,k) be outcome measure e for individual i of gender g measured at age a in period t, given that t is k periods away from an event of interest; i.e., the death of a parent. Furthermore, let \(( {\overline t_i ,\overline a_i } )\) denote the time period and age at which individual i experienced the event (k = 0). We can then write the expected outcome conditional on distance from the event relative to the expected outcome for the same age group and period, but unconditional on the distance to the event, as \(\mu_{ek} = \mathop E\limits_i \left[ {\frac{y_{ei} \vert k}{\mathop E\limits_j \left[ {y_{ej} \vert \left[ {g=g_i ,a=\overline a_i +k,t=\overline t_i +k} \right]} \right]}} \right].\)

Our starting point is the 308,706 individuals who lost a lone parent in Norway between 1993 and 2005; see Table 1. We disregard individuals who lost a lone parent more than once during the relevant time-period (this is possible if the parents are divorced). We also disregard individuals who died themselves before 2005. The net dataset then consists of 295,282 individuals. Outcomes are included for age >34 years, since non-employment (and low earnings) for younger persons often reflects participation in higher education.

For the social security outcome, we only have data from 1993; i.e., t = 1993,...,2005. In addition, we estimate models with monthly social security outcomes with t = 1993.1,,...,2005.12.

Our models are fully saturated in the time/age-space. Since we include individual fixed effects, a separate dummy for each possible cohort-year combination implies that one multicollinear vector is introduced for each cohort. Hence, one normalization is required for each cohort in this model.

The reference levels are chosen simply be computing averages for all observations available 9–15 years before lone parents’ deaths. For employment, these reference levels are 92% for men and 76% for women. For social security dependency, the reference levels are 22% for men and 28% for women.

It would be interesting to calculate the total economic costs of private care for a single parent. One approach that has been taken in Negera (2009) is to do a cost-benefit analysis of introducing a paid leave for 10 days a year to take care of an elderly parent. He finds that depending on the assumptions made, the informal care leave arrangement can be both socially profitable or/and socially unprofitable.

The number of days for which employees could take out unpaid leave was raised to 60 in 2010.

References

Baltagi BH (2008) Econometric analysis of panel data, 4th edn. Wiley, Chichester

Bolin K, Lindgren B, Lundborg P (2008) Your next of kin or your own career? Caring and working among the 50+ of Europe. J Health Econ 27(3):718–738

Bonsang E (2009) Does informal care from children to their elderly parents substitute for formal care in Europe? J Health Econ 28(1):143–154

Callegaro L, Pasini G (2007) Social interaction effects in an inter-generational model of informal care giving. Working Paper no 10, Department of Economics, University of Venice

Carlsen B (2008) Dobbeltmoralens voktere? Intervjuer med fastleger om sykemelding. Tidsskr Velferdsforsk 11(4):259–275

Carmichael F, Charles S (1998) The labor market costs of community care. J Health Econ 17(6):747–765

Carmichael F, Charles S (2003) The opportunity cost of informal care: does gender matter? J Health Econ 22(5):781–803

Chang CF, White-Means SI (1995) Labor supply of informal caregivers. Int Rev Appl Econ 9(2):192–205

Emanuel EJ, Fairclough DL, Slutsman J et al (1999) Assistance from family members, friends, paid care givers, and volunteers in the case of terminally ill patients. N Engl J Med 341(13):956–963

Engers M, Stern S (2002) Long-term care and family bargaining. Int Econ Rev 43(1):73–114

Ettner SL (1995) The impact of “parent care” on female labor supply decisions. Demography 32(1):63–80

Ettner SL (1996) The opportunity cost of elder care. J Hum Resour 31(1):189–205

Fevang E, Kverndokk S, Røed K (2008) A model for supply of informal care to elderly parents. Hero Working Paper No 2008: 12, University of Oslo

Gautun H (2003) Økt individualisering og omsorgsrelasjoner i familien. Omsorgsmønstre mellom middelaldrende kvinner og menn og deres gamle foreldre. Report 420, FAFO, Oslo

Gautun H (2008) Hvordan kombinerer eldre arbeidstakere jobb med omsorgsforpliktelser for gamle foreldre? Søkelys på arbeidslivet 25(2):171–185

Hægeland T, Kirkebøen LJ (2007) Lønnsforskjeller mellom utdanningsgrupper. SSB Notat 2007/36 (www.ssb.no/emner/06/90/notat_200736/notat_200736.pdf)

Halvorsen E, Thoresen TO (2005) The relationship between altruism and equal sharing. Evidence from inter vivos transfer behavior. Discussion Papers No 439, Statistics Norway, Research Department

Heitmueller A (2007) The chicken or the egg? Endogeneity in labor market participation of informal carers in England. J Health Econ 26(3):536–559

Heitmueller A, Michaud P-C (2006) Informal care and employment in England: evidence from the British household panel survey. IZA Discussion Paper No 2010

Herolfson K, Daatland SO (2001) Ageing, intergenerational relations, care systems and quality of life—an introduction to the OASIS project. NOVA Report 14/2001, NOVA—Norwegian Social Research

Hilbe JM (2009) Logistic regression models. Chapman & Hall/CRC, New York

Holtz-Eakin D, Joulfaian D, Rosen HS (1993) The Carnegie conjecture: some empirical evidence. Q J Econ 108(2):413–436

Jiménez-Martín S, Vilaplana Prieto C (2011) The trade-off between formal and informal care in Spain. Eur J Health Econ. doi:10.1007/s10198-011-0317-z

Joulfaian D, Wilhelm MO (1994) Inheritance and labor supply. J Hum Resour 29(4):1205–1234

Konrad K, Künemund H, Lommerud KE et al (2002) Geography and the family. Am Econ Rev 92(4):981–998

Kuhn M, Nuscheler R (2007) Optimal public provision of nursing homes and the role of information. Rostock centre discussion paper No 13, Rostock centre for the study of demographic change

Langset B (2006) Arbeidskraftbehov i pleie-og omsorgssektoren mot år 2050. Økonomiske analyser 2006(4):56–61

MaCurdy TE (1981) An empirical model of labor supply in a life-cycle setting. J Polit Econ 89(6):1059–1084

Marmot M (2004) The status syndrome. How social standing affects our health and longevity. Time Books, New York

Michael RT (1973) Education in nonmarket production. J Polit Econ 81(2):306–327

Motel-Klingebiel A, Tesch-Roemer C, von Kondratowitz H-J (2005) Welfare states do not crowd out the family: evidence for mixed responsibility from comparative analyses. Ageing Soc 25:863–882

Negera K (2009) An informal care leave arrangement—an economic evaluation. Master thesis, Institute of Health Management and Health Economics, University of Oslo

Nocera S, Zweifel P (1996) Women’s role in the provision of long-term care, financial incentives, and the future financing of long term care. In: Eisen R, Sloan FA (eds) Long-term care: economic issues and policy solutions. Kluwer, Boston, pp 79–102

OECD (2005) Ensuring quality long-term care for older people. Policy Brief, March 2005

Polder JJ, Barendregt JJ, Van Oers H (2006) Health care costs in the last year of life—the Dutch experience. Soc Sci Med 63:1720–1731

Rainer H, Siedler T (2009) O brother, where art thou? The effects of having a sibling on geographic mobility and labor market outcomes. Economica 76(303):528–556

Røed K, Strøm S (2002) Progressive taxes and the labor market: is the trade-off between equality and efficiency inevitable? J Econ Surv 16(1):77–111

Romøren TI (2003) Last years of long lives. The Larvik study. Routledge, London

Seshamani M, Gray A (2004) Time to death and health expenditure: an improved model for the impact of demographic change on health care costs. Age Ageing 33:556–561

Spiess CK, Schneider AU (2003) Interactions between care-giving and paid work hours among European midlife women, 1994 to 1996. Ageing Soc 23:41–68

Spillman BC, Lubitz J (2000) The effect of longevity on spending for acute and long-term care. N Engl J Med 342:1409–1415

Vaage OF (2002) Til alle døgnets tider. Tidsbruk 1971–2000. Statistisk sentralbyrå, Oslo-Kongsvinger

Van Houtven CH, Norton EC (2004) Informal care and health care use of older adults. J Health Econ 23(6):1159–1180

Wolf DA, Soldo BJ (1994) Married women’s allocation of time to employment and care of elderly parents. J Hum Resour 29(4):1259–1276

Wolff JL, Dy SM, Frick KD et al. (2007) End-of-life care. Findings from a national survey of informal caregivers. Arch Intern Med 167(1):40–46

Acknowledgements

This research is part of the Frisch Centre project 1135 “The public long-term care and its effect on labor market participation for elderly workers”, financed by the Norwegian Research Council through the Welfare Research Program. Data made available by Statistics Norway have been essential for the project. Thanks to Simen Gaure for programming assistance and to Heidi Gautun, Tor Iversen, Jos van Ommeren, two anonymous referees and, the Editor for valuable comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Responsible editor: Christian Dustmann

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fevang, E., Kverndokk, S. & Røed, K. Labor supply in the terminal stages of lone parents’ lives. J Popul Econ 25, 1399–1422 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-012-0402-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-012-0402-3