Abstract

This paper investigates the impact on cohabitation behavior of the introduction and dispersion of the birth control pill in the USA during the 1960s and early 1970s. A theoretical model generates several predictions that are tested using the first wave of the National Survey of Families and Households. Empirically, the causal effect is identified by exploiting plausibly exogenous variation in state laws granting access to the pill to unmarried women under age 21. The evidence shows that the pill was a catalyst that increased cohabitation’s role in selecting marriage partners, but did little in the short run to promote cohabitation as a substitute for marriage.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Economists have been interested in who matches with whom at least since Becker (1973).

The New York Times. 1962. “Cornell Ponders Rules of Conduct: University Code Reviewed After Student is Ousted,” October 4, p. 72.

The New York Times. 1968. “An Arrangement: Living Together for Convenience, Security, Sex,” March 3, p. 40.

Time. 1977. “Just Call Him Mister,” February 21. http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,918659-1,00.html.

Some women went abroad to get an abortion. For example, Linda LeClair, the Barnard College sophomore, stated that she and her boyfriend flew to Puerto Rico to get an abortion. Shortly thereafter, she started on the pill.

The initial thrust toward the development of the pill can be attributed to Margeret Sanger. She long envisioned the concept of the pill and, by securing an initial small grant through Planned Parenthood, convinced Gregory Pincus to embark on a research that eventually lead to Enovid, the first birth control pill. Two other key players were Katherine Dexter McCormick and John Rock. McCormick, Sanger’s acquaintance and sympathizer, provided the majority of the funding for Pincus’ research. Since only physicians could run clinical trials and Pincus was a biologist, Rock, who was a physician, became instrumental once it came time to run the Puerto Rico-based clinical trials. See Asbell (1995) for more on the history of the pill.

According to the FDA, the pill is even more effective than female sterilization when used correctly. With typical use, the pill is three times more effective than condoms, which is the most effective barrier method of birth control. (http://www.fda.gov/fdac/features/1997/conceptbl.html, accessed 3/19/07.) The intrauterine device (IUD) is also a very effective means of birth control and was available before the pill. It also had the advantage of disentangling sex from contraception, but it could not decouple contraception from sex organs; the IUD requires insertion by a physician. The IUD was rarely used (Zelnik and Kantner 1977).

Currently cohabiting individuals and singles under 35 were asked to rate the importance of several reasons to and not to cohabit. The reasons to cohabit were: it requires less personal commitment than marriage, it is more sexually satisfying than marriage, it makes it possible to share living expenses, it requires less sexual faithfulness than marriage, couples can make sure they are compatible before getting married, and it allows each partner to be more independent than does marriage. The reasons not to cohabit that respondents rated were: it is emotionally risky, my friends disapprove, my parents disapprove, it is morally wrong, it is financially risky, it requires more personal commitment than dating, it requires more sexual faithfulness than dating.

Interestingly, 28% reported that an important reason not to cohabit was that it requires more sexual faithfulness than dating. This is peculiar since sexual faithfulness appears to be one dimension of greater commitment, so we would expect this percentage to be less than 27. However, the difference in percentages is not statistically significant. As a point of interest, of the 2,709 respondents who replied to both questions, 488 rated sexual faithfulness as (strictly) more important than greater commitment as a reason not to cohabit.

At first blush, it may seem surprising that respondents report that mate screening is the primary function of cohabitation since considerable evidence shows that marriages preceded by cohabitation are less stable than those not preceded by cohabitation. This is the wrong comparison to make when evaluating this claim, however, since those who cohabit are likely to be systematically different from those who do not. See Brien et al. (2006) on this important point; their paper finds strong evidence that cohabitation plays a screening role.

The assumption that marriage is irreversible is made for parsimony. As long as the cost of divorce exceeds the cost of breaking off a cohabitation, the implications of the model relevant to the empirical questions in this paper would not change.

This is because the probability that a women marries or enters a permanent cohabitation with the person she is currently dating is at least πp > 0. (It equals π for those women who marry without cohabiting first.) The probability she breaks up is at most 1 − πp. It therefore follows that she will be in a committed relationship with probability 1 as time approaches infinity: πp + (1 − πp)πp + (1 − πp)2 πp + ⋯ = 1.

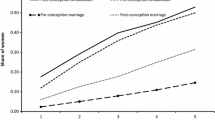

In the figure, however, women are classified as a noncohabitor or learner only if they married by age 27. Some women in each of these groups marry at later ages. However, I restricted the sample to women who marry by age 27 for consistency; women born in 1960 were 27 years old at the time of a 1987 interview. The figures are qualitatively similar if one considers an older cohort (e.g., 1935–1950) and an appropriately extended maximum age at first marriage (e.g., 37 years old).

This assumption implies that the pill increases the welfare of all women. This seems reasonable if the fact that fewer women marry when young has spillover effects that further increase selectivity into marriage, and hence improve the quality of a matches. That is, the pill directly causes some women to delay marriage, and this increases the opportunity cost of marriage (k) for everyone since the pool of unmarried men grows and one is more likely to meet attractive mates when the pool is larger (Goldin and Katz 2002).

An additional underpinning to this assumption is provided in Chiappori and Oreffice (2008). See Akerlof et al. (1996), for a model where the pill makes some women worse off, however.

In fact, women in the transition era will become increasingly selective as time approaches t ∗ since the anticipated increase in k becomes less distant.

Connecticut even had a law on the books that prohibited the use of contraceptives, but the Supreme Court ruled in Griswold v. Connecticut (381 U.S. 479 1965) that barring married couples from using contraception violated the marital right to privacy. Seven years later, the Court ruled that a Massachusetts law prohibiting the distribution of contraceptives to unmarried individuals violated the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment (Eisenstadt v. Baird, 405 U.S. 438 1972).

As argued in Rosenfeld and Kim (2005), having been born out of state may also serve as a good proxy for a willingness to break social and community norms, a characteristic which may be correlated with pill use and cohabitation. Hence this regression will also test the independence of treatment to a willigness to break norms.

GK show that the ELA postively affected the fraction of college graduate women that go on to pursue a professional degree. However, except in a small number of cases, is unlikely to affect the probability a woman completes high school since most graduates complete high school by age 18 or 19. Even so, this is not a concern in this test if the coefficient on high school completion is zero.

To further solidify the case for random timing, Bailey empirically investigates the relationship between the timing of legal access and various state characteristics (demographic, social, technological, and those relating to the labor market). Remarkably, the only characteristic that is statistically significant is the percent of the state’s population that is Catholic. As in Bailey, I control for this using state fixed effects. Cohort fixed effects control for norms which evolve over time. Conditional on these fixed effects, it seems reasonable to conclude that women in this quasi-experiment are randomly assigned to the environment in which they respond to ELA.

Guldi (2008) provides careful research on the timing of early access to abortion. Early access to abortion is coded as 1970 for Alaska, California, Hawaii, New York and Washington, and 1972 is coded for Vermont and New Jersey. All other states permitted legal access with Roe v. Wade in 1973. This is the same coding used in Bailey (2006). For divorce laws I use coding from Wolfers (2006).

Ideally I would like to estimate Pr (cohabit with first spouse), a probability which presumes marriage. I actually estimate Pr (cohabit with first spouse, marry by age 27), and since all evidence and intuition suggest that ELA delays marriage, the impact of ELA on the latter probability will be smaller compared to its impact on the former.

An alternative would be to restrict the sample to women who married by age 27, which entails estimating the conditional probability

$$ \Pr (\text{cohabit with f\/irst spouse marry by age 27})= \frac{\Pr (\text{cohabit with f\/irst spouse, marry by age 27})}{\Pr (\text{marry by age 27})}. $$However, we cannot say whether the estimated impact of ELA on this conditional probability is higher or lower than its impact on Pr (cohabit with first spouse) since ELA lowers Pr (marry by age 27). Therefore, one cannot claim that the estimated coefficient on ELA is a lower bound when estimating the conditional probability.

The data set also allows me to determine whether a woman lived with anyone prior to her first marriage. The results are robust to using this metric of pre-marital cohabitation as the dependent variable.

Recall that the analysis estimates the impact of granting access to the pill to young, unmarried women. The impact on first-spouse cohabitation of introducing the pill to the entire population would likely be larger in magnitude.

Results from age 28 onwards would be biased downwards without trimming the sample like this. Consider the probability of having been married by age 28. The value of the dependent variable among those born in 1960 (and are therefore 27 at the time of interview) is mechanically the same as when the evaluating the probability of having been married by age 27. For every other cohort we would expect an increase in the number of observations with a value of one. Thus, the estimate of μ would be lower if the 1960 cohort were mistakenly included.

References

Akerlof GA, Yellen J, Katz M (1996) An analysis of out-of-wedlock childbearing in the United States. Q J Econ 111(2):277–317

Allyn D (2000) Make love not war: the sexual revolution: an unfettered history. Little, Brown, and Company, Boston

Asbell B (1995) The pill: a biography of the drug that changed the world. Random House, New York

Bailey (2006) More power to the pill: the impact of contraceptive freedom on women’s life cycle labor supply. Q J Econ 121(1):289–320

Bailey MJ, Hershbein B, Miller AR (2010) The opt-in revolution: contraception, women’s labor supply, and the gender gap in wages. University of Virginia. Available at http://economics.stanford.edu/files/Bailey10_6.pdf

Becker GS (1973) A theory of marriage: part I. J Polit Econ 81(4):813–846

Brien MJ, Lillard LA, and Stern S (2006) Cohabitation, marriage, and divorce in a model of match quality. Int Econ Rev 47(2):451–494

Chiappori PA, Oreffice S (2008) Birth control and female empowerment: an equilibrium analysis. J Polit Econ 116(1):113–140

Christensen F (2009) Learning by dating, commitment, and assortative mating. Towson University. Available at http://pages.towson.edu/fchriste/research

Coontz S (2005) Marriage, a history: how love conquered marriage. Penguin, New York

Garris L, Steckler A, McIntire JR (1976) The relationship between oral contraceptives and adolescent sexual behavior. J Sex Res 12(2):135–146

Goldin C, Katz LF (2002) The power of the pill: oral contraceptives and women’s career and marriage decisions. J Polit Econ 110(4):730–770

Guldi M (2008) Fertility effects of abortion and birth controll pill access for minors. Demography 45(4):817–827

Hirsch B (1976) Living together: a guide to the law for unmarried couples. Houghton Mifflin, Boston

Ihara TL, Warner RE, Hertz F (2006) Living together: a legal guide for unmarried couples, 13th edn. NOLO

Kiernan K (2002) Cohabitation in Western Europe. In: Booth A, Crouter AC (eds) Just living together: implications of cohabitation on families, children, and social policy. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Mahwah, NJ 3-32

Pope H, Knudsen DD (1965) Premarital sexual norms, the family, and social change. J Marriage Fam 27(3):381–402

Rosenfeld MJ, Kim B (2005) The independence of young adults and the rise of interracial and same-sex unions. Am Sociol Rev 70(4):541–562

Smock PJ (2000) Cohabitation in the United States: an appraisal of research themes, findings, and implications. Annu Rev Sociology 26:1–20

Stevenson B, Wolfers J (2007) Marriage and divorce: changes and their driving forces. J Econ Perspect 21(2):27–52

Sweet J, Bumpass L, Call V (1998) The design and content of the national survey of families and huseholds. NSFH Working Paper #1

Wolfers J (2006) Did unilateral divorce raise divorce rates? A reconciliation and new results. Am Econ Rev 96(5):1802–1820

Zelnik M, Kantner JF (1977) Sexual and contraceptive experience of young unmarried women in the united states. Fam Plann Perspect 9(2):55–71

Acknowledgements

I am grateful for helpful comments and suggestions I received from Chad Meyerhoefer, Juergen Jung, Ari Kang, and seminar participants at Towson University, the Agency for Health Care Research and Quality, and the Midwest Economics Association. I am also grateful to two anonymous referees whose comments greatly improved the paper. Any errors are my own.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Responsible Editor: Junsen Zhang

Appendix

Appendix

Lemma 4

Assume conditions 1–3. A woman will advance a dating relationship to marriage or cohabitation if she sees x 1 = h, and will break off the relationship otherwise. In addition, a woman who is currently cohabiting will break off the cohabitation if she observes x 2 = l, and will continue cohabiting or choose to marry otherwise.

Proof

Firstly, consider a woman who is dating and observes x 1 = l. If she chooses to marry or cohabit with her partner, her payoff would be − ∞ . Continually dating her partner gives a lifetime utility of \(\frac{ k+\varepsilon _{i}}{1-\delta }>-\infty .\) But breaking up and searching for a new partner is the best option because she receives k + ε i in every period of dating and there is a strictly positive probability that x 1 = h with the next person she dates. When this happens, she can increase her expected flow payoff to \(\max \left\{ pq_{h}+(1-p)q_{l}+k+\varepsilon _{i},pq_{h}+(1-p)q_{l}\right\} >k+\varepsilon _{i}\) by choosing cohabitation or marriage. (Recall that pq h + (1 − p)q l > 0).

Now consider a woman who is dating and observes x 2 = h. If she chooses to break up (or to continually date), she receives \(\frac{k+\varepsilon _{i} }{1-\delta }\) in lifetime expected utility. Marriage gives an expected lifetime utility of \(\frac{pq_{h}+(1-p)q_{l}}{1-\delta },\) and cohabitation gives an expected lifetime utility of at least \(\frac{pq_{h}+(1-p)q_{l}+k+ \varepsilon _{i}}{1-\delta }\) since this would be the expected lifetime utility to cohabitation if cohabitation were irreversible. Hence, choosing cohabitation or marriage is optimal since this gives at least \(\max \left\{ \frac{pq_{h}+(1-p)q_{l}+k+\varepsilon _{i}}{1-\delta },\frac{ pq_{h}+(1-p)q_{l}}{1-\delta }\right\} >\frac{k+\varepsilon _{i}}{1-\delta }.\)

Now consider a woman who observed x 1 = h while dating, chose cohabitation and observes x 2 = h. The highest possible flow payoff any woman can achieve is \(\max \left\{ q_{h}+k+\varepsilon _{i},q_{h}\right\} \), so it follows that any woman will lock in this payoff by choosing either a permanent cohabitation or to marry.

Finally, consider a woman who observed x 1 = h while dating, chose cohabitation and observes x 2 = l. Breaking up results in a payoff equal to \(V_{i}^{d}-c\) and continually cohabiting or marrying results in a payoff equal to \(\max \left\{ \frac{q_{l}+k+\varepsilon _{i}}{1-\delta },\frac{q_{l} }{1-\delta }\right\} .\) We must show \(V_{i}^{d}-c>\max \left\{ \frac{ q_{l}+k+\varepsilon _{i}}{1-\delta },\frac{q_{l}}{1-\delta }\right\} .\)

Firstly, consider the case k + ε i ≥ 0. We must show \( V_{i}^{d}-c>\frac{q_{l}+k+\varepsilon _{i}}{1-\delta }.\) But \( V_{i}^{d}\geq \frac{k+\varepsilon _{i}}{1-\delta }\) since one can guarantee \( \frac{k+\varepsilon _{i}}{1-\delta }\) by continually dating, so it is sufficient to show \(\frac{k+\varepsilon _{i}}{1-\delta }-c>\frac{ q_{l}+k+\varepsilon _{i}}{1-\delta },\) or \(-c\geq \frac{q_{l}}{1-\delta },\) but this is true by assumption.

Next consider the case k + ε i < 0. We must show \(V_{i}^{d}-c> \frac{q_{l}}{1-\delta }.\) Suppose instead that \(V_{i}^{d}-c\leq \frac{q_{l} }{1-\delta }.\) Then a woman will convert her cohabitation to marriage regardless of the realization of x 2 since we know she will do so if x 2 = h. Consequently \(V_{i}^{c}=\frac{pq_{h}+(1-p)q_{l}}{1-\delta } +k+\varepsilon _{i}\). But then \(V_{i}^{c}<\frac{pq_{h}+(1-p)q_{l}}{ 1-\delta },\) and the individual would not be cohabiting in the first place. That is, she would have chosen marriage over cohabitation upon seeing x 1 = h while dating, a contradiction.□

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Christensen, F. The pill and partnerships: the impact of the birth control pill on cohabitation. J Popul Econ 25, 29–52 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-010-0344-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-010-0344-6