Abstract

Transitions from unemployment into temporary work are often succeeded by a transition from temporary into regular work. This paper investigates whether temporary work increases the transition rate to regular work. We use longitudinal survey data of individuals to estimate a multi-state duration model, applying the ‘timing of events’ approach. The data contain multiple spells in labour market states at the individual level. We analyse results using novel graphical representations, which unambiguously show that temporary jobs shorten the unemployment duration, although they do not increase the fraction of unemployed workers having regular work within a few years after entry into unemployment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Labour markets in many countries have displayed increases in flexible jobs—particularly temporary jobs. An extensive debate has explored the extent to which such jobs improve welfare and help individual workers. It is often argued that the existence of temporary work is especially beneficial to currently unemployed workers because it provides them opportunities to gain work experience and acquire human capital, to deepen the attachment to the labour market and to search more effectively for more desirable jobs. Temporary job experience may reveal information regarding the ability and motivation of the individual (screening or signalling). Some studies show that employers indeed use atypical contracts as a way of screening for permanent jobs (e.g. Storrie 2002; Houseman et al. 2003). Our paper examines the extent to which temporary work facilitates individual unemployed workers to move from unemployment to regular work—that is, the extent to which temporary work acts as a stepping stone towards regular work. Some recent studies consider the effect of temporary work on long-run employment outcomes using models without potentially selective unobserved heterogeneity (Amuedo-Dorantes 2000; Hagen 2003). Hagen found a stepping-stone effect of temporary work in Germany; Amuedo-Dorantes found none for Spain. Gagliarducci (2005) considers the effect of the number of temporary jobs, taking selection effects into account.

Our empirical analysis follows the ‘timing of events’ approach formalised by Abbring and Van den Berg (2003). We use longitudinal survey data of individuals to estimate a multi-state duration model. The model specifies the transition rates from unemployment to temporary jobs, from temporary jobs to regular work and from unemployment directly to regular work. Each transition rate is allowed to depend on observed and unobserved explanatory variables as well as on the elapsed time spent in the current state. To deal with selection effects, we allow the unobserved determinants to be dependent across transition rates. For example, if more motivated individuals have not only less trouble finding permanent jobs but are also over-represented among those in temporary jobs, then a casual observer who does not take this into account may conclude that there is a positive causal effect even if, in reality, there is none.Footnote 1 We also exploit subjective responses on whether the individual desires to have a regular job. We exploit the multi-spell nature of the data to reduce the dependence of the results on functional form specifications. The ‘timing of events’ approach exploits variation in observed moments of transitions in order to distinguish empirically between causal effects and selection effects. Expressed somewhat informally, if a transition to a temporary job is often quickly succeeded by a transition into a regular job, for any constellation of explanatory variables, then this is strong evidence of a causal effect.Footnote 2

This paper adopts the specific model framework developed by Van den Berg et al. (2002),Footnote 3 for two reasons. First, their framework allows in a natural way for ‘lock-in’ effects of temporary jobs (meaning that they may involve a temporary standstill of search activities for other jobs). Secondly, it allows for heterogeneous treatment effects (meaning that the effect of having a temporary job on the transition rate to regular work may vary across observed and unobserved individual characteristics). Because of lock-in effects and effect heterogeneity, the parameter estimates are hard to interpret. We contribute to the methodological literature by analysing this in some detail and by developing a graphical procedure to express the main results.

The estimation results also shed light on whether individuals with a high incidence and/or duration of unemployment flow into temporary work more often and whether they benefit more from the stepping-stone effect of temporary work. More generally, we address whether individuals who benefit from temporary work also have a high transition rate into temporary work. This is important from a policy point of view. If certain types of individuals hardly ever flow into temporary work (although their average duration until regular work would be substantially reduced by it), then it may be sensible to stimulate the use of temporary work among this group, for example by helping individuals to register at temporary work agencies.

We abstract from effects of the existence of temporary jobs on the transition rate from unemployment directly into regular work (i.e. without an intervening temporary work spell). It can be argued that this effect is negative if a temporary job facilitates a move to a regular job and if unemployed individuals are aware of this. The data, however, do not allow for identification of this effect. We also abstract from equilibrium effects. Temporary employment might improve the economic performance of firms because there is less need to hoard workers as an insurance against a sudden upswing in demand (Pacelli 2006; Kahn 2000; Von Hippel et al. 1997). The use of temporary workers may also reduce cyclical swings in labour productivity, since firms might be better able to shed workers quickly during a downturn (Estevão and Lach 1999). Moreover, temporary contracts imply lower layoff costs and could thus stimulate employment creation. The literature is not unanimous, however, on the issue of how temporary employment affects the overall employment level. The overview study of Ljungqvist (2002) shows that early general equilibrium analyses by Burda (1992), Hopenhayn and Rogerson (1993) and Saint-Paul (1995) display a negative effect of firing costs on employment, whereas later general equilibrium models by Alvarez and Veracierto (2001) and Mortensen and Pissarides (1999) conclude that firing costs affect employment positively. Ljungqvist shows that the results of these theoretical models depend crucially on the model features and assumptions.Footnote 4 Also, partial equilibrium models (such as Bentolila and Saint-Paul 1992, 1994; Bentolila and Bertola 1990; Aguirregabiria and Alonso-Borrego 2008) and empirical work (e.g. Hunt 2000; Bentolila and Saint-Paul 1992; Aguirregabiria and Alonso-Borrego 2008) are inconclusive.

To the extent that the data allow it, we examine how job characteristics of regular jobs depend on whether they were directly preceded by a spell of unemployment or whether there was an intermediate spell of temporary work (see also Booth et al. 2002; Houseman 2003).Footnote 5

Our results show that temporary jobs shorten the unemployment duration but do not increase the probability of obtaining regular work within a few years after entry into unemployment. Regular jobs found via temporary jobs do pay higher wages than regular jobs found directly from unemployment.

The paper is organised as follows. Section 2 discusses the Dutch case of temporary employment. Section 3 presents the model and defines the outcome measures of our analysis. Section 4 presents the dataset, defines temporary jobs, discusses some variables that we use in the analyses and provides descriptive statistics. Section 5 discusses the estimation results, which are illustrated with some graphical overviews. We draw conclusions on the stepping-stone effect of temporary employment, covariate effects, the role of unobserved heterogeneity and the quality of the jobs found. Section 6 concludes.

2 Temporary employment in the Netherlands

The Netherlands is an interesting case for studying the effects of temporary employment. For decades, the Netherlands has been a frontrunner in temporary agency work, with little restrictions on its use (Grubb and Wells 1993; OECD 1999; CIETT 2000; Eurociett 2007). In 1999, the remaining restrictions on the use of agency work in transportation and construction were removed. Now, only for seamen, a restriction is in place. The share of agency work in overall employment is approximately 5% (CIETT 2000). In the beginning of the 1990s, this was approximately 2% (Grubb and Wells 1993).

Regarding fixed-term employment, the Netherlands is not very strictly regulated either (Grubb and Wells 1993; OECD 1999, 2004). Since long, employers in the Netherlands are allowed to use these contracts without many restrictions. The main restriction concerns the number of consecutive fixed-term contracts allowed. Until 1999, only one subsequent fixed-term contract was allowed; since 1999, three consecutive fixed-term contracts can be used. The share of fixed-term employment in the overall employment rate is approximately 15%. In the beginning of the 1990s, this was about 9% (Grubb and Wells 1993). Approximately 60% of new jobs are fixed term (these and other figures are from the national labour inspection). A special case is the fixed-term contract with an explicit agreement to convert into an open-ended contract in case of good performance. This agreement can be legally enforced, irrespective whether the intention is made on paper or verbal. More than half of all fixed-term contracts are concluded on this basis (Fouarge et al. 2006). As we shall argue later, we exclude this type of fixed-term contracts in our analysis from our definition of temporary jobs.

On-call contracts are the most flexible direct hire labour contract available. Since the 1980s, these contracts have been used on a rather large scale. In 1997, 13% of private sector employment was on an on-call basis, which by 2003 was reduced to 5%. Until 1999, there were no conditions on the maximum duration of zero-hour contracts and min–max contractsFootnote 6 and the minimum number of hours paid per call. Since 1999, when the Flexibility and Security Act was enacted, there is a minimum number of hours paid, and the maximum duration of the fully flexible contract is restricted to the first 6 months.

OECD (2004) empirically established that temporary employment is positively related to employment protection of open-ended employment contracts. Employment protection for open-ended contracts in the Netherlands is rather strict (OECD 1999, 2004). The Dutch system is rather complicated and scores especially high on procedural inconveniences. There are no severance payments by law if the dismissal is handled by the employment office (CWI).Footnote 7 However, if the employer files for permission by a labour court, the court may determine severance pay, roughly according to the formula: 1 month/year of service for workers <40 years of age; 1.5 months for workers between age 40 and 50; 2 months for workers 50 years and over. Approximately half of all dismissals is handled by the employment office, the other half goes through labour court.

3 Model specification

3.1 Transition rates

This paper applies the ‘timing of events’ methodology. We adopt the model framework of Van den Berg et al. (2002), which was constructed to study the use of trainee positions in the Dutch medical profession. In our context, the model specifies the transition rates from unemployment to temporary employment, from unemployment to regular employment and from temporary employment to regular employment. In general, the transition rate or hazard rate θ ij is defined as the rate at which an individual flows from one state i to another state j, given that (s)he survived in state i until the current moment. We define the indices i and j to have the following values: U = unemployment, T = temporary employment and R = regular employment. We specify a mixed proportional hazard model for each transition rate. Let observed characteristics be denoted by x and the baseline hazard by λ ij (.), for the transition rate from state i to state j. In addition, β ij is a vector of parameters to be estimated. The multiplicative unobserved random terms v ij are state- and exit-destination-specific. Then,

and the corresponding survival function equals

Note that this imposes that the hazard rates depend only on the elapsed duration in the current state and not on earlier outcomes.Footnote 8

We define an unemployment spell as the time span between entry into unemployment and entry into either regular or temporary work. A temporary job spell is defined as the time span between the start of the first temporary job and entry into regular employment. Thus, a temporary job spell may consist of multiple periods of (short) unemployment and temporary job spells. The total spell between the start of unemployment and regular employment is the sum of the unemployment spell and, if applicable, the temporary job spell. In our data, we observe more than one of these ‘total’ spells per individual. For a given individual, the values of v ij of the same kind are assumed to be identical across different spells. The unobserved heterogeneity terms v ij capture selective inflow into temporary work and permanent work. For example, the observed transition rate from temporary work to regular work may be higher than the observed rate from unemployment to regular work just because individuals for whom it is easy to find regular work tend to self-select into temporary work. Then, v UT is positively related to v UR and v TR . It is also possible that persons who most easily find regular work find or accept a temporary job less quickly, which means that v UT and v UR are negatively related. With unobserved heterogeneity, the likelihood function is not separable in the parameters of different transition rates. Abbring and Van den Berg (2003) analyse the identification of these types of models. The availability of multiple spell data is useful in the sense that fewer assumptions are needed for identification, and the empirical results are, therefore, less sensitive to aspects of the model specification.Footnote 9 In particular, in multi-spell duration analysis, as in fixed-effects panel data analysis, the results do not critically depend on the assumption that observed and unobserved explanatory variables are independent.

An important condition for identification concerns the absence of anticipation of the moment of the start of a temporary job. This means, essentially, that the individual should not know more about the moment this job starts than is captured by the modelled distribution of the duration until the start of a temporary job. In our context, anticipation occurs if the individual stops looking for regular work (or, more generally, decreases his transition rate into regular work) at the moment that it becomes certain that he will enter a temporary job in a certain time period from now. If this were the case, and the researcher does not observe the moment of this decision, then the estimates of current transition rates are determined by future events. As far as we know, there are no numbers available on this phenomenon. The scenario seems unlikely to be distorting in the present set-up. From a dynamic (search) point of view, it is unlikely that people know in advance the exact moment at which they will find a temporary job. In any search model, the moment at which a match between a worker and a temporary job is realised is not fully in the hands of the unemployed worker, especially since temporary workers are often called at short notice. The worker can, at most, determine the rate at which the match is realised, and this leaves some randomness in the realised moment. This implies that the way in which search frictions are usually modeled—as random arrivals of trading opportunities—has fruitful applications in the literature on treatment evaluation, and we use it as such in this paper. Against this, one may argue that some individuals are registered at temporary work agencies as looking for such jobs; this is unobserved, however, and these individuals may have a higher rate of moving from unemployment to temporary work. This is captured in our model as unobserved and observedFootnote 10 heterogeneity. The model framework we use is designed to disentangle selection effects from causal effects. This selection effect can certainly be a self-selection effect (as is the case if some individuals search for temporary jobs and others do not).

3.2 Parameterisation

We follow the literature by taking the duration dependence functions (or baseline hazards) λ ij (t) to have piecewise constant specifications. We subdivide a duration axis into eight quarterly intervals for the first 2 years, followed by two half-year intervals for the third year, and an open interval for durations of more than 3 years. These intervals capture the empirical shapes rather well.

We directly follow the specifications of Card and Sullivan (1988) and Van den Berg et al. (2002) for the multivariate distribution of the unobserved heterogeneity terms. Let v ijn denote a realisation of the random variable v ij . Types of individuals are characterised by a unique set of values of v UT , v UR , v TR . The application used in this study allows for two possible realisations for each v ij , so n = 1,2. We take the locations of the mass points as well as the associated probabilities to be unknown parameters. In addition, we impose the condition that if v UR = v URn then v TR = v TRn . This effectively assumes that individuals who more easily find regular work from unemployment also find regular work more easily from a temporary position. This specification results in four different types of individuals (four different combinations of mass points) and six mass point parameters. Note that the combination of mass points (v UT , v UR , v TR ) replaces the constants in the vector of regression coefficients and, thus, are identified. The relation between the elements of (v UT , v UR , v TR ) does not need to be monotone. As mentioned before, the extent to which v UT is related to v UR and v TR determines the extent to which selectivity affects the association between having had temporary work or not on the one hand and entering regular work on the other.

3.3 Quantities of interest

3.3.1 Stepping-stone effect

The stepping-stone effect is defined as the increase in the hazard rate of finding regular employment as a result of the acceptance of a temporary job. This stepping-stone effect is not represented by a single model parameter. To see this, note that in our parameterization, the transition rate from unemployment into regular work depends on the time elapsed since entry into unemployment (t), whereas the rate from temporary work to regular work depends on the time elapsed since entry into temporary work (τ). Both of these exhibit distinctive duration dependence patterns. It would be absurd to only allow for dependence on the duration since entry into unemployment, in light of the fact that temporary jobs may involve a lock-in effect, causing the transition rate into regular work to be lower right after having entered a temporary job and higher some time later. As a result, the causal effect of having moved into temporary work at a given time t UT on the individual transition rate into regular work at time t > t UT , compared to not having entered temporary work until and including t, equals \(\dfrac{\theta _{TR} \left( {t,\tau \left| x \right.,v_{TR} } \right)}{\theta _{UR} \left( {t\left| x \right.,v_{UR} } \right)}-1\), where t = t UT + τ. This means that a comparison of the hazard rate from unemployment to (regular) work with and without the treatment cannot be represented by one parameter. Of course, it is still interesting to examine the duration dependence patterns and average levels of transitions into regular work. For example, if for an individual with given values of x and v, it always holds that \(\theta _{TR} \left( {\tau \left| x \right.,v_{TR} } \right)>\theta _{UR} \left( {t\left| x \right.,v_{UR} } \right)\), then the individual effect of temporary jobs on the duration until regular work is positive at all points of time. The results are presented in Section 5.1.

3.3.2 Share of individuals finding regular employment via temporary work

Given the complexity of the model, a quantitative assessment of the over-all effect of temporary work is more easily studied with an outcome measure that aggregates over effects on instantaneous transition rates, than by studying the instantaneous transition rates themselves. For this purpose, we use the cumulative probability of moving into a regular job, measured at various points of time after entry into unemployment. Therefore, we compare the (cumulative) probability of moving into regular work directly from unemployment with the (cumulative) probability of moving into regular work from unemployment via temporary work. We quantify these probabilities by using the estimated model. The cumulative probability of moving into regular work within t periods after having entered unemployment equals

where the indices of S refer to the corresponding duration variable (i.e. S UT is the survivor function of the duration from unemployment into temporary work). The first part of the expression equals the probability of moving into regular work by way of a direct transition from unemployment, whereas the second part equals the probability of moving into regular work by way of temporary work. Logically, the probability of moving into regular work directly from unemployment does not converge to 1 as t goes to infinity, if θ UT > 0. The relevant population estimate of Eq. 1 follows by integration of the total expression over the distribution of observed and unobserved characteristics.

The decomposition of Eq. 1 into its two terms does not capture a causal effect of temporary work. To see this, note that both terms are positive even if there is no effect at the individual level (i.e. if the states of unemployment and temporary work are equivalent in the sense that the transition rate from temporary work to regular work at any calendar time point equals the transition rate from unemployment to regular work that would have prevailed at that point). Instead, the decomposition of Eq. 1 represents the population fraction of unemployed individuals who find regular work through either the temporary work channel or the direct channel. Results of this decomposition are presented in Section 5.2.

3.3.3 Effect of temporary work on the probability of regular employment

One can define a sensible average causal effect of temporary work on the probability of having had regular work at t periods after entry into unemployment, by comparing the actual magnitude of Eq. 1 to the magnitude in a situation where temporary employment is not available. We can quantify the probability of regular work within t periods in the absence of temporary work by imposing in Eq. 1 that the transition rate into temporary work θ UT equals zero, resulting in the expression \(\int\limits_0^t \theta_{U\!R}(y) S_{U\!R}(y)dy\). This holds both for the general model parameterisation in which θ TR is also allowed to depend on the time t since entry into unemployment, as well as for our actual parameterisation.Footnote 11 This is demonstrated formally in the Appendix. The effect that we calculate here may be called a time-aggregated stepping-stone effect. It captures to what extent the duration until regular work is shortened by the existence of temporary jobs. Results of this effect are presented in Section 5.3.

Some comments are in order. First, in the absence of temporary work, some of the individuals who would otherwise have moved into regular work by way of a temporary job move into regular work directly from unemployment. Therefore, the cumulative fraction of individuals moving into regular work that we calculate exceeds the observed fraction of individuals who move directly from unemployment into regular work. The estimated cumulative probability of moving into regular work from unemployment, which in the presence of temporary work converges to one minus the cumulative probability of moving into temporary work from unemployment, is thus extrapolated to converge to 1 as t goes to infinity. This assumes the same pattern of duration dependence and relative effects of the explanatory factors. This means that we abstract from potential effects of the mere existence of temporary jobs on the transition rate from unemployment directly into regular work. In particular, this rules out that unemployed individuals make their search effort for regular jobs dependent on the availability of temporary jobs. Second, all these calculations at the micro-level assume that on the macro level the absence of temporary jobs does not affect the magnitude of the direct transition rate from unemployment to regular work (recall the discussion in Section 1). Among the many reasons why this assumption may be incorrect is the possibility of equilibrium effects on the demand and supply of regular jobs. Third, it is not possible to test non-parametrically whether the curve described by (1) is different from the curve obtained by imposing θ UT = 0, simply because the curve obtained by imposing θ UT = 0 is counterfactual and therefore cannot be estimated non-parametrically.

3.3.4 Effect of temporary work on the probability of employment

Another effect of temporary work can be defined as the effect of temporary employment on the probability of having started regular or temporary employment at t periods after entry into unemployment. This is one minus the probability of still being unemployed at t. The cumulative probability of moving into regular or temporary work within t periods after having entered unemployment equals

By analogy to the quantification of the effect of temporary jobs on the probability of regular work, the effect of temporary jobs on the employment probability can be quantified by imposing in Eq. 2 the condition that the transition rate into temporary work θ UT equals zero, resulting in the expression \(\int\limits_0^t {\;\theta _{U\!R} (y)\,S_{U\!R} (y)\,dy} \).

The difference between these two expressions captures the extent to which unemployment is shortened by the existence of temporary employment. Even if we do not find an effect of the existence of temporary work on the probability of regular work (as described in Section 3.3.3), we might find an effect on the unemployment probability if the temporary job spell is simply an alternative for an equally long time searching from unemployment. Results of this analysis are presented in Section 5.4.

4 Data

This paper uses a sub-sample of the OSA labour supply panel, which is a longitudinal panel dataset collected by the Dutch Institute for Labour Studies (OSA). It follows a random sample of Dutch households over time since 1985, by way of biannual face-to-face interviews. The survey concentrates on individuals between the ages of 16 and 64 years, and who are not full-time students. For more background information on the data, the effect of attrition and references to other studies using these data, see e.g. Van den Berg and Lindeboom (1998) and Van den Berg et al. (1994). We use data from 1988 to 2000. Our sample consists of all survey participants who became unemployed at least once during this period. For this group, we analyse the unemployment duration and search durations until temporary and regular employment for a maximum of three unemployment spells per individual. This results in a sample of 976 individuals, with a total number of 1,175 unemployment spells.

People are defined as unemployed when they do not have a job but are looking for one. One does not need to receive unemployment benefits to be unemployed. We define regular work as being in a job that is a permanent job or being in a job with a limited-duration contract with an explicit agreement to become permanent in case of good performance. We define temporary jobs as more contingent types of jobs: fixed-term jobs without an explicit agreement to become permanent, temporary agency work, on-call contracts and subsidised temporary jobs. It should be noted that in the Netherlands, contrary to certain other countries, unemployed individuals who are registered at commercial temporary work agencies, but are currently not assigned to an employer, do not receive wage income and are considered to be unemployed. This also applies to our data. Some studies treat part-time employment as a form of non-standard employment. Since most part-time employment in the Netherlands is on a voluntary basis, we treat part-time employment in the same way as regular employment. This implies that it can be either regular or temporary, depending on the duration of the contract. Our classification of temporary versus regular jobs does not exclude the possibility that a regular job can be a bad job as well. Table 1, however, indicates that if we consider wages and training opportunities, the regular jobs obtained by previously unemployed workers are, on average, more attractive than the temporary jobs.

Table 2 provides the labour market positions of our sample at two consecutive interview dates. Remember that everyone in our sample is unemployed at least once during the period 1988–2000. As a result, transitions to unemployment are higher than in a random sample of the Dutch workforce. The transition rates are roughly consistent with earlier findings both in the Netherlands and other Western countries (e.g. Dekker 2007, p. 133; Segal and Sullivan 1997). Transitions from temporary jobs to regular work are frequent; indeed, they are more frequent than transitions from unemployment to regular work.

In the OSA panel, an effort is made to collect extensive information on the labour market histories of the individual respondents. Individuals are asked about their labour market status 2 years ago (the previous interview date), about all transitions made since then, and about their current labour market status. For every transition, we observe when it happened, why it happened, by which channel the new position was found and what the respective labour market positions were. Regarding the labour market position after a change, individuals can choose from the following: other function with same employer, employee at other employer, self-employed, co-working partner of self-employed, no paid job but looking for one, no paid job and not looking for one, military service and full-time education. From these labour market histories, we obtain both the sequence of labour market states occupied and the sojourn times in these states. Figure 1 shows the total number of observed labour market transitions in our sub sample. Note that some types of transitions do not play a role in the empirical analysis below (in particular, the transitions to and from ‘not in the labour force’, the transitions to unemployment and the transitions from regular employment to temporary employment). This is due to an insufficient number of observations of such transitions.

With regard to the employment positions at the survey moments, we observe the wage, number of hours worked, industry, occupation, type of work and type of contract. Less information is available for periods between survey moments, which leads to two problems. First, we do not observe many characteristics of jobs that start and end between two consecutive interviews. Notably, we often do not observe the wage of such jobs.Footnote 12 This implies that the set of explanatory variables that we can use is restricted mostly to background characteristics of the individual (listed in Table 3).Footnote 13 Second, it is not always clear whether a job that begins and ends between two consecutive interviews is temporary or not. In case of doubt, we infer the type of contract from other variables. We use the stated channel by which the job was found (this can be a temporary help agency) and the stated reason why transitions into and out of the job are made (to get more job security or because of the end of contract, respectively). In some cases, these variables are missing, and we right-censor the unemployment spell at the moment of the transition into such a job. The latter occurred in 12% of all spells.

Because we know the sequence of labour market states occupied and the sojourn times in these states, we can determine the unemployment spell—the duration between the start of unemployment and the moment at which the individual moves into either regular or temporary work—and the temporary job spell—the duration from the start of a temporary job until the moment at which the individual moves to a regular job. A temporary job spell ends with a regular job at the same employer or at another employer. We do not distinguish between these possibilities. Summary statistics for the unemployment spells and temporary job spells are given in Table 3. As mentioned in Section 3, the latter duration period may include intermittent temporary jobs and periods of unemployment in-between. Only 12% of all temporary job spells contain an intermittent period of unemployment. As Table 3 shows, a temporary job spell consists on average of 1 month of unemployment and 19 months of employment in temporary job(s).

All of these durations may be right-censored due to a transition to another labour market state or due to reaching the end of the observation window. We do not include unemployment spells that started before the first interview, so there are no left-censoring problems that arise with interrupted spells.Footnote 14

5 Estimation results

5.1 Stepping-stone effect

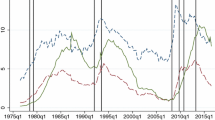

We now discuss the results for the complete model.Footnote 15 We start with the shapes of the individual transition rates as functions of the elapsed durations in the states under consideration. Given the initial level of a transition rate (i.e., upon entry into the state under consideration), the shape of this rate is described by the parameters of the duration dependence function (see the estimates in Table 4 and Fig. 2). Apart from these duration dependence parameters, the specifications only include time-invariant covariates. The rate into temporary work from unemployment is smaller than the rate into regular work. However, once an individual is in temporary employment, the rate of flowing into regular work is at some time after the start of the search larger than otherwise. One might expect workers who accept a temporary job to be initially strongly attached to that job—for example, for contractual reasons. This is true in some sense. Newly employed temporary workers have a slightly lower rate into regular work than unemployed workers. Until 1 year after the start of the temporary job, the transition rate to regular work is lower than the transition rate from unemployment to regular work. After a period of 1.5 years, however, the transition rate from temporary into regular employment increases substantially. This does not correspond to any binding legal restriction in the length of temporary work (see Section 2), as in e.g. Guell and Petrongolo (2007). After 30 months, we are left with only 225 observations in the data, which makes the estimated hazards, and the observed jumps in the transition rates, rather imprecise. The jumps in the hazard rates could be due to the loss of wage-related unemployment benefits for many of the unemployed. As the typical time between consecutive panel survey waves is 2 years, recall errors in responses on retrospective transitions could explain some heaping in durations around 2 years, but this does not explain jumps or heaping after 2 years.Footnote 16

The finding that the transition rate from temporary work to regular work increases during the temporary job indicates that the accumulation of human capital may be a major reason for employers to prefer individuals who have occupied a temporary job. An increasingly larger social network among employed workers may also explain this. Apparently, for prospective employers, being in a temporary job constitutes more than just a (positive) signal that one has been found acceptable for such a job. As mentioned before, temporary job spells may include periods of intermittent unemployment. Obviously, human capital and social networks do not expand during these intermittent periods of unemployment. As shown in Section 4, this holds true for only 12% of all temporary job spells. As a sensitivity analysis, we include a dummy variable for these observations as an additional covariate. The main results are unaffected by this (these and other non-reported estimates are available on request). In particular, the estimated time-aggregated effects on probabilities (see Subsections 5.3 and 5.4 below) are virtually equal to those for the baseline model.

In another sensitivity analysis, we estimate an extended model in which the transition rate from temporary work to regular work depends on the time spent unemployed before entry into the temporary job (as an additional covariate). The corresponding coefficient is insignificant.

In the main set of results, transitions to non-participation are treated as censored at the moment of such a transition. As a sensitivity analysis, we excluded the 120 observations for whom a transition to non-participation was observed. This did not result in any major changes in estimated coefficients.

Note that the results are not due to selection effects, since we corrected for observed and unobserved heterogeneity. As indicated earlier, the selection effect for which we correct might well be a self-selection effect, as is the case if some individuals search for temporary jobs and others do not. This selection is captured as unobserved and observed heterogeneity with, respectively, the mass points for unobserved heterogeneity and an explanatory variable indicating whether the unemployed individual prefers temporary work to regular work. Because the unobserved heterogeneity terms correct for the fact that individuals that are still in unemployment at long durations have low job-finding probabilities, the estimated hazard rates in a model without unobserved heterogeneity terms are higher at low durations and lower at long durations than in Fig. 2. This holds true especially for transitions from unemployment.

5.2 Share of individuals finding regular employment via temporary work

We now turn to the quantification of the share of individuals finding regular employment via temporary work, as presented in Section 3.3.2. The solid curve in Fig. 3 displays the cumulative probability of moving into regular work, whether directly or via the temporary work channel, as a function of the time elapsed since entry into unemployment. This is obtained by using the estimated model to calculate expression (1) for each individual in the sample and for all possible combinations of v ij ’s weighted by the estimated p’s. Similarly, the dashed curve visualises the probability of moving into regular work without an intermediate spell of temporary work, applying the decomposition of expression (1) as described in Section 3.3.2. After 6 months, 12% of the flow into regular work consisted of transitions through temporary work, while after 72 months, this percentage increased to 43%.

5.3 Effect of temporary work on the probability of regular employment

Figure 4 describes the effect of temporary work on the probability of having had regular work as defined in Subsection 3.3.3. The dashed curve in Fig. 4 plots the estimated counterfactual cumulative probability of moving into regular work if there is no temporary employment. This is obtained by imposing in Eq. 1 the condition that the transition rate into temporary work equals zero, taking again averages across individuals in the sample and across the v ij ’s. For comparison, the solid curve of Fig. 3 is repeated in Fig. 4. The two curves are virtually the same, indicating that on average, the probability of finding regular work is the same in a situation with temporary employment as it is in a situation in which no temporary employment exists. If anything, the cumulative probability of moving to regular employment is, at some points, slightly lower in a situation with temporary employment. The lock-in effect of temporary work is then, on average, slightly larger than the positive effect of temporary work on reaching regular work. Later, subsections examine whether this result is uniformly valid for all types of individuals. Estimates of a model without unobserved heterogeneity show a similar effect.

5.4 Effect of temporary work on the probability of employment

Figure 5 shows the effect of the existence of temporary jobs on the probability of (re)employment as defined in Subsection 3.3.4. The dashed curve in Fig. 5 plots the estimated cumulative counterfactual probability of moving into work if there is no temporary employment. This is obtained by imposing in Eq. 2 the condition that the transition rate into temporary work equals zero, taking averages across individuals in the sample and across the v ij ’s. The solid curve of Fig. 5 presents the (re)employment probability in the factual situation, in which regular and temporary jobs coexist. The job-finding probability in the situation without temporary employment is smaller than in the situation in which temporary work exists. As the elapsed time since the start of unemployment increases, the job-finding probability in the absence of temporary employment slowly converges to the job-finding probability in the situation where temporary employment exists. Thus, although temporary employment does not increase the probabilities of finding a regular job, it does lead to a decrease in the unemployment duration. Instead of being unemployed, people are employed in temporary jobs. We should note that the temporary employment spell, as we defined it, may include periods of unemployment, but as was shown in Section 4, this is only true for a minority of cases.

Figure 5 does not directly provide an estimate of the over-all effect of the existence of temporary jobs on the over-all employment rate. To gauge the order of magnitude of this, without the need to estimate and simulate a flexible meta-model that allows for all possible transitions, we abstract from duration dependence and heterogeneity, and we rely on external sources to estimate the transition rate from employment to unemployment. Van den Berg and Ridder (1998) use Dutch data from the same period as in this paper to obtain a monthly estimate of 0.005. Using slightly more recent data, and correcting for structural unemployment, Ridder and Van den Berg (2003) obtain an estimate of 0.0074. With a transition rate from unemployment to employment equal to 0.03 without temporary work, and equal to 0.045 with temporary work (Figs. 2 and 5; recall from the previous subsection that the probability of moving to regular work is similar in both cases), we find that the employment rate increases by four or by six percentage points due to the existence of temporary jobs. As we do not account for transitions from regular work to temporary work and back to regular work, these numbers may slightly underestimate the total effect.

5.5 Covariate effects

In this section, we examine whether the results presented in the previous sections are uniformly valid for all types of individuals. Table 5 presents the covariate effects on the individual transition rates. Note that a positive sign indicates a higher transition probability and a shorter duration. Comparison of the coefficients for “unemployment to regular” with the coefficients for “temporary to regular” reveals the variation of the stepping-stone effect across different types of individuals. Comparison of the coefficients for “unemployment to regular” with those for “unemployment to temporary” reveals the take-up of the stepping-stone pathway.

Transition rates into regular work are higher in labour markets with many vacancies per unemployed individual. This is generally found in the literature. This relation, however, does not hold for the rate into temporary work, since this rate seems to be less sensitive to business cycle fluctuations. This effect was also found for Spain in the study by Bover and Gómez (2004), which also showed that (in general) it is easier to become employed if one wants to work more hours—although males seem to find temporary work more easily if they prefer to work part-time. Older unemployed individuals need more time to move into regular and temporary positions, as do individuals from the ethnic minorities group. Unemployed individuals who prefer temporary work to regular work do not, as might be expected, often make the direct transition from unemployment to a regular job.

Having a partner has a strong positive effect on the direct transition from unemployment to regular work. This effect is well known (for an overview of studies on this issue, see Ginter and Zavodny 2001). There is no generally accepted reason for this phenomenon. Partners may make individuals more productive and, therefore, more attractive to employers. Alternatively, individuals who are successful on the labour market may have characteristics that also make them attractive on the marriage market. The effect we find is larger for working partners than for non-working partners, which supports the selection hypothesis.

Men with children at home have a higher transition rate from temporary to regular work. These men may be under greater pressure to provide a satisfactory level of family income and thus may be eager to transform their insecure temporary job into a more secure regular position. We also find a negative effect for men with a partner, perhaps indicating that having a partner reduces the urgency for provision of a satisfactory level of family income by the man alone.

5.5.1 Stepping-stone effect heterogeneity

The variation of the stepping-stone effect across different types of individuals is revealed by the comparison of the coefficients for “unemployment to regular” with the coefficients for “temporary to regular”. From a policy perspective, it is particularly interesting to focus on disadvantaged groups, notably ethnic minorities (defined as the four largest groups originating from Surinam, the Netherlands Antilles, Morocco and Turkey), the low-educated and women. For example, Netherlands Statistics notes that non-western ethnic minorities have unemployment rates that are more than four times as high as native Dutch individuals—in 2003, 17.6% versus 4.3% (unemployment benefits and social assistance). The stepping-stone effect may be larger for ethnic minorities if employers who are reluctant to hire them can use temporary contracts to screen them. In that case, it makes sense to stimulate unemployed immigrants to register at temporary work agencies. Table 5 shows that there is a difference between male and female ethnic minorities. The stepping-stone effect is much higher for male ethnic minorities than for native Dutch males, since the coefficient for temporary to regular work is positive and the coefficient from unemployment to regular work is negative. Clearly, this supports policy measures that stimulate the use of temporary work by ethnic minorities—for example, by helping them to register at temporary work agencies. For females, both coefficients for ethnic minorities are smaller than for native Dutch females—even more so for temporary to regular work than from unemployment to regular work. This implies a smaller stepping-stone effect for women from ethnic minorities than for native Dutch women.

The stepping-stone effect varies with other characteristics as well. It is higher for the low educated than for the high educated, for men compared to women, for singles compared to persons with a partner, for men preferring part-time work compared to men preferring full-time work, for people preferring regular work compared to those preferring temporary work and for people in the Randstad compared to those in other regions.

5.5.2 Use of the stepping-stone pathway

Given the presence of a stepping-stone effect, comparison of the coefficients for “unemployment to regular” with those for “unemployment to temporary” sheds light on the relevance of the pathway through temporary work to regular work. In the better phase of the business cycle, with many vacancies and low unemployment, the use of temporary jobs as stepping-stones is smaller than in recessions. With respect to ethnic minorities, an eye-catching result is that ethnic minorities, both males and females, make little use of temporary jobs. For male ethnic minorities, we established the substantial potential benefit of temporary employment as a stepping stone towards regular work. This adds to the support for policy measures that stimulate the use of temporary work by ethnic minorities. The same holds true for individuals with low education levels. Compared to more highly educated individuals, they have a higher potential benefit from temporary jobs, but they use it less often.

With regard to other characteristics, the use of temporary employment is higher for men compared to women, for men without children compared to men with children, for women with children compared to those without children, for singles compared to individuals with a partner and for men preferring full-time jobs compared to men preferring part-time work.

It is the combination of the stepping-stone effect and the take-up that determines the actual effects of temporary jobs. To illustrate this, Fig. 6a, b shows the equivalents of Figs. 4 and 5 for male ethnic minorities versus native Dutch men. As these figures show, the men from the ethnic minority group experience a greater stepping-stone effect than native Dutch men. Their probability of having found regular work after 6 years is 4.3 percentage points (or 6%) higher in a situation with temporary employment than in the situation without. For native men, we see no such effect. The effect of temporary work on the total probability of employment is larger for native men than for those from ethnic groups. Native Dutch men have an 11 percentage points (or 13.5%) higher probability of having found employment in a situation with temporary employment than in a situation without this type of work. For ethnic men the difference is nine percentage points (or 12.5%).

a Estimated cumulative probability of finding regular work, with and without temporary employment, for males from ethnic minorities versus native Dutch men. b Estimated cumulative reemployment probability, with and without temporary employment, for males from ethnic minorities versus native Dutch men

5.5.3 Unobserved heterogeneity

Table 6 presents the estimates of the parameters of the unobserved heterogeneity distribution. As always, in models with unobserved heterogeneity, the heterogeneity distribution estimates are difficult to interpret. First, they are determined by the set of included covariates. Secondly, the discrete heterogeneity distribution should be interpreted as an approximation of the true distribution. We merely make two remarks. First, the variances and correlations of the unobserved heterogeneity terms are significantly different from zero. This implies that a model that does not take the selection into temporary work into account is misspecified and leads to incorrect inference. Secondly, we use likelihood ratio tests to test our model against models without unobserved heterogeneity terms and with more heterogeneity terms. None of the models was found to be preferable to the current model. The main results are insensitive to the assumed family of discrete unobserved heterogeneity distributions.

5.6 Quality of jobs found

A limitation of analyses of the effects of temporary work on the duration until regular work is that they typically ignore effects on the type and quality of the accepted job. Our dataset supplies job characteristics at survey dates of jobs held at survey dates, but it does not supply job characteristics otherwise (like at the moment of job acceptance or in between survey dates). We observe the wage for 379 of the total of 507 regular jobs in our sample, whereas other job characteristics are even less frequently observed. Table 7 presents estimates of a random effect analysis of the hourly wage in these 379 jobs. Results indicate that regular jobs that are found directly pay lower wages than regular jobs found by way of temporary work. Table 8 presents estimates of a logit analysis on the availability of employer provided training. In this dimension, regular jobs do not differ from regular jobs found via temporary work. Some studies analyse the effect of non-standard employment on health insurance (e.g. Ditsler et al. 2005). For the Netherlands, this is not a relevant question since each Dutch citizen is covered by health insurance.

The data also allow us to address the stability of jobs. We extend our main model with the duration of the regular job, where the way in which the job is found—directly or by way of temporary employment—is used as an explanatory variable. With respect to the unobserved heterogeneity mass-point distribution, we assume that the unobserved heterogeneity regarding the duration of the regular job is positively related to the unobserved heterogeneity in the transition from unemployment to regular employment and the transition from temporary to regular employment. Table 9 reports the estimated coefficients of the hazard rate of the regular-job duration. As a sensitivity analysis, we also estimate a model in which the above assumption concerning the signs of the relations between the unobserved-heterogeneity terms is relaxed, resulting in eight instead of four mass points. According to a likelihood ratio test, the more general model does not give a better fit than the restricted model presented in Table 9. A positive sign indicates a higher transition rate out of work and a shorter duration of the regular job. The results indicate that the duration of the regular job does not depend on whether it is directly preceded by a temporary job or by unemployment. If anything, regular jobs that are found directly from unemployment last shorter than regular jobs found via temporary work. Simple t tests (Table 10) also show that the reason why people separate from their regular job does not differ significantly between directly and indirectly found regular jobs. Regarding the exit state, there is a slight difference: jobs found by way of temporary employment end less often in unemployment and more often in a transition to another temporary job. However, this difference is not statistically significant.

6 Conclusion

This paper analysed the effect of temporary employment for the employment opportunities of unemployed individuals. The stepping-stone effect, defined as the increase in the hazard rate of finding regular employment as a result of the acceptance of a temporary job, is not represented by a single model parameter in the current set-up. Examining duration dependence patterns indicates that newly employed temporary workers have a slightly lower rate into regular work than unemployed workers. Workers who accept a temporary job are initially strongly attached to that job. The exit rate from temporary work, however, becomes higher than the exit rate from unemployment after 1.5 years in temporary employment. The fact that the transition rate from temporary work to regular work increases during the temporary job indicates that the accumulation of human capital may be a reason for employers to prefer individuals who have occupied a temporary job. An increasingly larger social network among employed workers may also explain this.

As we have shown in this paper, the over-all effect of temporary work is more easily studied with an outcome measure that time aggregates over effects on instantaneous transition rates, than by studying the instantaneous rates themselves. For this purpose, we have used the cumulative probabilities of moving into a regular job, measured at various points of time after entry into unemployment. After 6 months, 12% of the flow into regular work consists of transitions through temporary work, while after 6 years, this increases up to 43%. The probability of having had regular work within a certain amount of time after entry into unemployment is not affected by the existence of temporary jobs. This probability hardly differs from the counterfactual situation without temporary work. The effect of temporary work on the unemployment duration is unambiguously negative. In sum, even though individuals need to search as long for a regular job as in the absence of temporary jobs, they are employed in temporary positions instead of being unemployed all the time. All of these results are obtained while correcting for selection effects associated with moving into temporary work. We should re-emphasise that we abstract from the potentially negative effects of the existence of temporary jobs on the transition rate from unemployment directly into regular work (i.e. without intervening temporary job spell) and from equilibrium effects of a general increase in temporary work. With this caveat in mind, it is worthwhile to mention that in a specific sense, our results do not lend support to the often-heard claim that temporary jobs substitute away regular jobs. Specifically, the acceptance of a temporary job does not lead an individual to spend less time in regular work. Also, we found evidence that regular jobs found by way of temporary jobs pay higher wages than regular jobs taken directly from unemployment.

The stepping-stone results apply for virtually all workers, including those with a relatively weak labour market position. We have shown that the stepping-stone effect is somewhat higher for the low-educated than for higher-educated workers, for (male) ethnic minorities compared to native Dutch, for men compared to women and for singles compared to persons with a partner. However, groups differ not only with respect to the potential advantage temporary work offers them as a stepping-stone but also regarding the take-up of temporary work (and thus of the stepping-stone). The use of temporary employment is higher for men compared to women and for singles compared to individuals with a partner. Ethnic minorities are a special case in this respect. Although male ethnic minorities experience a high stepping-stone effect on the transition rate to regular work, they rarely flow into temporary jobs, so they do not benefit from the effect. This suggests that policy measures should be taken to stimulate the use of temporary work by ethnic minorities, for example by helping them to register at temporary work agencies.

Notes

The approach does not require exclusion restrictions, instrumental variables, or conditional independence assumptions. Recently, a number of studies have appeared in which the ‘timing of events’ approach is applied to analyse the effects of dynamically assigned treatments on duration outcomes (see Abbring and Van den Berg 2004, for an overview).

Chalmers and Kalb (2001) employed the same method to analyse the effect of casual jobs (i.e. those without holiday and sick leave entitlements), using the Survey of Employment and Unemployment patterns 1994–1997 from the Australian Bureau of Statistics.

In search and matching models with the standard assumption of a constant relative split in the match surplus between firms and workers, layoff costs tend to increase employment by reducing labour reallocation, whereas employment effects tend to be negative in models with employment lotteries due to the diminished private return to work.

In this type of contract the minimum and sometimes maximum number of hours worked per week are put down in the contract.

If the employer can prove to the employment office that a dismissal is legitimate, he gets a layoff permit, which means he does not have to pay any severance payment. A dismissal is legitimate in case of financial necessity, unsuitability or blameworthy behaviour of the employee.

With individual-specific random effects, including individual past labour market outcomes as explanatory variables is difficult as it gives rise to initial-conditions problems, unless the data contain a natural starting point of each individual labour market history, like the moment of school-leaving. We therefore do not include such past outcomes. By implication, the individual treatment effects defined below do not directly depend on e.g. past annual earnings, but at most on the observed and unobserved determinants of past outcomes. Wooldridge (2005) develops an alternative approach to deal with initial-conditions problems in dynamic panel data. This involves specifying the individual effect in terms of the initial observed value of the outcome and in terms of exogenous variables. This approach is less suitable for our purposes, because the length of the first spell is often not observed due to left-censoring. Additional practical concerns are that the number of observed previous spells and the number of panel survey interviews vary across individuals, and that we have multi-dimensional unobserved individual effects and outcomes, exacerbating the computational costs.

See also Abbring and Van den Berg (2004) for comparisons to inference with latent variable methods and panel data methods.

The data contain an explanatory variable indicating whether the individual, when unemployed, prefers temporary work to regular work.

The fact that we allow β UR to be different from β TR and that we allow v UR /v TR to be different across individuals means that we allow the individual effects of temporary work to differ between individuals. The average effects can then be obtained by averaging the individual effect over x and v.

We observe the wage for 379 of the total of 507 regular jobs that are found by our sample after their spell of unemployment.

Information on the labour market tightness, particularly the unemployment/vacancy ratios per education level at the start of unemployment, comes from Netherlands Statistics (CBS).

Strictly speaking we do not solve for initial conditions since we do not fully observe the previous employment history of all cases.

The estimates were computed with GAUSS, using the standard maximum likelihood application MAXLIK. The programming of the likelihood function was based on a range of available programs for the “Timing of Events” approach. The likelihood function of the base model was optimized in 265 iterations, using the Broyden, Fletcher, Goldfarb and Shanno (BFGS) optimization algorithm and a numerical gradient with a tolerance level of 10 − 4 for the gradient of the estimated coefficients. Identical results were obtained using different numbers of individuals, a wide range of different starting values, and different optimization algorithms (like the Newton-Raphson method and the Berndt, Hall, Hall and Hausman method).

Recall errors may also result in the non-observation of short spells. This has been studied extensively in French longitudinal panel survey data on employment outcomes (see Van den Berg and Van der Klaauw 2001, for an overview) and the results have been found to be rather insensitive to this, with the exception of seasonal effects which are not a concern in the present paper.

References

Abbring JH, Van den Berg GJ (2003) The non-parametric identification of treatment effects in duration models. Econometrica 71(5):1491–1517

Abbring JH, Van den Berg GJ (2004) Analyzing the effect of dynamically assigned treatments using duration models, binary treatment models, and panel data models. Empir Econ 29(1):5–40

Aguirregabiria V, Alonso-Borrego C (2008) Labor contracts and flexibility: evidence from a labor market reform in Spain. Working Paper, Department of Economics, University of Toronto, Toronto

Alvarez F, Veracierto M (2001) Severance payments in an economy with frictions. J Monet Econ 47(3):477–498

Amuedo-Dorantes C (2000) Work transitions into and out of involuntary temporary employment in a segmented market: evidence from Spain. Ind Labour Relat Rev 53(2):309–325

Amuedo-Dorantes C (2002) Work safety in the context of temporary employment: the Spanish experience. Ind Labour Relat Rev 55(2):262–285

Arulampalam W, Booth AL (1998) Training and labour market flexibility: is there a trade-off? Br J Ind Relat 36(4):521–536

Bentolila S, Bertola G (1990) Firing costs and labour demand: how bad is Eurosclerosis. Rev Econ Stud 57(3):381–402

Bentolila S, Saint-Paul G (1992) The macro-economic impact of flexible labor contracts, with an application to Spain. Eur Econ Rev 36(5):1013–1053

Bentolila S, Saint-Paul G (1994) A model of labour demand with linear adjustment costs. Labour Econ 1(3–4):303–326

Booth AL, Francesconi M, Frank J (2002) Temporary jobs: stepping-stones or dead ends? Econ J 112(June):F189–F215

Bover O, Gómez R (2004) Another look at unemployment duration: exit to a permanent job vs. a temporary job. Investig Econ 28(2):285–314

Burda M (1992) A note on firing costs and severance benefits in equilibrium employment. Scand J Econ 94(3):479–489

Card D, Sullivan DG (1988) Measuring the effect of subsidised training programs on movements in and out of employment. Econometrica 58(3):497–530

Chalmers J, Kalb G (2001) Moving from unemployment to permanent employment: could a casual job accelerate the transition? Aust Econ Rev 34(4):415–436

CIETT (2000) Orchestrating the evolution of private employment agencies towards a stronger society. CIETT, Brussels

Dekker R (2007) Non-standard employment and mobility in the Dutch, German and Britih labour market. Mimeo, University of Tilburg, Tilburg

Ditsler E, Fisher P, Gordon C (2005) On the fringe: the substandard benefits of workers in part-time, temporary, and contract jobs. Commonwealth Fund publication no. 879, Commonwealth Fund, New York

Estevão M, Lach S (1999) Measuring temporary labour outsourcing in US manufacturing. NBER Working Paper no. 7421, Cambridge, MA

Eurociett (2007) More work opportunities for more people; Unlocking the private employment agency industry’s contribution to a better functioning labour market. Eurociett, Brussels

Farber HS (1997) The changing face of job loss in the United States 1981–1995. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity. Microeconomics 55–128

Farber HS (1999) Alternative and part-time employment arrangements as a response to job loss. J Labor Econ 17(4):S142-S169

Feldman DC, Doerpinghaus HI, Turnley WH (2001) Managing temporary workers: a permanent HRM challenge. Organ Dyn 23(2):49–63

Fouarge D, Gielen A, Grim R, Kerkhofs M, Roman A, Schippers J, Wilthagen T (2006) Trendrapport aanbod van arbeid 2005. OSA Rapport A220, Organisatie voor Strategisch Arbeidsmarktonderzoek, Tilburg

Gagliarducci S (2005) The dynamics of repeated temporary jobs. Labour Econ 12(4):429–448

Ginter DK, Zavodny M (2001) Is the male marriage premium due to selection? The effect of shotgun weddings on the return to marriage. J Popul Econ 14(2):313–328

Grubb D, Wells W (1993) Employment regulation patterns of work in EC countries. OECD Econ Stud 21(Winter):7–58

Guell M, Petrongolo B (2007) How binding are legal limits? Transitions from temporary to permanent work in Spain. Labour Econ 14(2):153–183

Hagen T (2003) Do fixed-term contracts increase the long-term employment opportunities of the unemployed? ZEW Discussion Paper 03–49, Zentrum für Europäische Wirtschaftsforschung, Mannheim

Hopenhayn H, Rogerson R (1993) Job turnover and policy evaluation: a general equilibrium analysis. J Polit Econ 101(5):915–938

Houseman SN (2003) The benefits implications of recent trends in flexible staffing arrangements. In: Mitchell OA Blitzstein DS, Gordon M, Mazo JF (eds) Benefits for the workplace of the future. University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia, pp 89–109

Houseman SN, Kalleberg AL, Erickcek GA (2003) The role of temporary help employment in tight labor markets. Ind Labor Relat Rev 7(1):105–127

Hunt J (2000) Firing costs, employment fluctuations and average employment: an examination of Germany. Economica 67(266):177–202

Kahn S (2000) The bottom line impact of nonstandard jobs on companies’ profitability and productivity. In: Carré F, Ferber M, Golden L, Herzenberg S (eds) Nonstandard work: the nature and challenges of changing employment arrangements. Industrial Relations Research Association, Champaign, pp 21–40

Ljungqvist L (2002) How do lay-off costs affect employment? Econ J 12(482):829–853

Mortensen D, Pissarides C (1999) New developments in models of search in the labour market. In: Ashenfelter O, Card D (eds) Handbook of labour economics, vol 3B. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 2567–2627

OECD (1999) Employment protection and labour market performance. Employment outlook 1999. OECD, Paris, Chapter 2

OECD (2004) Employment protection regulation and labour market performance. Employment outlook 2004, OECD, Paris, Chapter 2

Pacelli L (2006) Fixed-term contracts, social security rebates and labour demand in Italy. Laboratorio R. Revelli, Turin

Purcell K, Hogarth T, Simm C (1999) Whose flexibility? The costs and benefits of non-standard working arrangements and contractual relation. Joseph Rowntree Foundation, York

Ridder G, Van den Berg GJ (2003) Measuring labor market frictions: a cross-country comparison. J Eur Econ Assoc 1(1):224–244

Saint-Paul G (1995) The high unemployment gap. Q J Econ 10(2):527–550

Segal LM, Sullivan DG (1997) The growth of temporary services work. J Econ Perspect 11(2):117–136

Storrie D (2002) Temporary agency work in the European Union. Mimeo, Department of Economics, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg

Van den Berg GJ, Lindeboom M (1998) Attrition in panel survey data and the estimation of multi-state labor market models. J Hum Resour 33(2):458–478

Van den Berg GJ, Ridder G (1998) An empirical equilibrium search model of the labor market. Econometrica 66(5):1183–1221

Van den Berg GJ, Van der Klaauw B (2001) Combining micro and macro unemployment duration data. J Econom 102(2):271–309

Van den Berg GJ, Lindeboom M, Ridder G (1994) Attrition in longitudinal panel data and the empirical analysis of labour market behaviour. J Appl Econ 9(4):421–435

Van den Berg GJ, Holm A, Van Ours JC (2002) Do stepping-stone jobs exist? Early career paths in the medical profession. J Popul Econ 15(4):647–666

Von Hippel C, Mangum SL, Greenberger DB, Heneman RL, Skoglind JD (1997) Temporary employment: can organizations and employees both win? Acad Manage Exec 11(1):93–104

Wooldridge JM (2005) Simple solutions to the initial conditions problem for dynamic, nonlinear panel data models with unobserved heterogeneity. J Appl Econ 20(1):39–54

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Dutch Institute for Labour Studies (OSA) for allowing us to use the OSA labour supply panel survey data. We thank the Editor, two anonymous Referees, participants at the IZA Summer School, ILM, EALE and ESWC Meetings, and the EC Workshop on Temporary Employment, as well as Laura Larsson, for useful comments.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Responsible editor: Christian Dustmann

Appendix: The effect of temporary jobs on the probability of moving into regular work

Appendix: The effect of temporary jobs on the probability of moving into regular work

Consider the model extension where θ TR depends on the time τ since entry into temporary work as well as on the current time t = τ + t UT since entry into unemployment, where t UT denotes the moment of the transition into temporary work, so θ TR = θ TR (τ, t). We define S TR (τ, t UT ) as the survival function of the duration in temporary work if the transition into in temporary work occurs at t UE , so

We have to modify Eq. 1 accordingly, to

Absence of treatment effects means that for all t and τ there holds that θ TR (τ,t) = θ UR (t). This implies that S TR (t − y,y) = S UR (t)/S UR (y). If we substitute this into Eq. 3 and elaborate on this then, we simply obtain S UR (t). The latter is also obtained if we substitute into Eq. 3 that θ UT = 0 (notice that the first parts of Eqs. 1 and 3 do not change when imposing that for all t and τ, there holds true that θ TR (τ,t) = θ UR (t)).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

de Graaf-Zijl, M., van den Berg, G.J. & Heyma, A. Stepping stones for the unemployed: the effect of temporary jobs on the duration until (regular) work. J Popul Econ 24, 107–139 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-009-0287-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-009-0287-y