Abstract

The paper re-examines the idea that a family can be viewed as a community governed by a self-enforcing constitution, and extends existing results in two directions. First, it identifies the circumstances in which a constitution is renegotiation-proof. Second, it introduces parental altruism. The behavioural and policy implications are illustrated by showing the effects of public pensions and credit rationing. These implications are not much affected by whether altruism is assumed or not, but contrast sharply with those of more conventional models.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

If grown-up children give attention to elderly parents, \(m_{1}\) is the difference between the money that the agent gives each of her children, maybe in the form of bequest, and the money equivalent of the utility of the attention that she receives from each of them.

Nothing of substance changes if we assume, instead, that they face a positive credit ration, lower than the cost of a child.

In a seminal paper, Browning (1975) makes the point that, as children do not vote, the pension system produced by a direct democracy will be larger than the one which maximizes the lifetime utility of the representative agent. At the family level, that is the same as saying that \(z\) will be set at zero, and \(x\) at the highest level compatible with Nash equilibrium. The role of a constitution is to prevent just that.

The risk is that a child will be unwilling, or unable to pay her parent \(x\) in old age. The former would occur if a change in the economic environment (e.g., a rise in \(r\)) made the constitution unviable, the latter if the child died before reaching adulthood, or were too poor to pay her dues.

May, rather than will as in the model without altruism, because \(x\) reduces the altruistic component of the agent’s utility.

In a stationary environment, we shall then have that

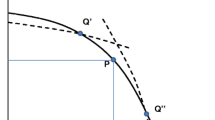

Taking fertility as exogenous, and interpreting \(z\) as educational investment, Anderberg and Balestrino (2003) show that, if the Nash constraint is binding, the renegotiation-proof constitution is inefficient in the usual Pareto sense. Under their assumptions, this implies that investment in the children’s education, rather than the children’s current consumption, will be too low.

Given the (subjective) certainty framework, we are obviously talking of an unexpected change.

The implicit pension tax is defined as the difference, at the date of retirement, between the capitalized value of the contributions, and the expected value of the benefits; see Sinn (1990).

References

Anderberg D, Balestrino A (2003) Self-enforcing transfers and the provision of education. Economica 70:55–71

Baland JM, Robinson A (2002) Rotten parents. J Public Econ 84:341–356

Becker GS, Barro RJ (1988) A reformulation of the economic theory of fertility. Q J Econ 103:1–25

Becker GS, Murphy KM (1988) The family and the state. J Law Econ 31:1–18

Bernheim BD, Ray D (1989) Collective dynamic consistency in repeated games. Games Econom Behav 1:295–326

Browning EK (1975) Why the social security budget is too large in a democratic society. Econ Inq 13:373–388

Cigno A (1993) Intergenerational transfers without altruism: family, market and state. Eur J Polit Econ 9:505–518

Cigno A, Rosati FC (1996) Jointly determined saving and fertility behaviour: theory, and estimates for Germany, Italy, UK, and USA. Eur Econ Rev 40:1561–1589

Cigno A, Rosati FC (2000) Mutual interest, self-enforcing constitutions and apparent generosity. In: Gérard-Varet LA, Kolm SC, Mercier Ythier J (eds) The economics of reciprocity, giving and altruism. MacMillan and St. Martin’s, London

Cigno A, Casolaro L, Rosati FC (2002) The impact of social security on saving and fertility in germany. FinanzArchiv 59:189–211

Cigno A, Giannelli GC, Rosati FC, Vuri D (2007) Is there such a thing as a family constitution? A test based on credit rationing. Review of Economics of the Household, forth

Di Tella R, MacCullogh R (2002) Informal family insurance and the design of the welfare state. Econ J 112:481–503

Duesenberry J (1960) Comment on G. Becker, “An economic analysis of fertility”. In: NBER (ed) Demographic and economic change in developed countries. Princeton Univ. Press, Princeton

Guttman JM (2001) Self-enforcing reciprocity norms and intergenerational transfers. J Public Econ 81:117–151

Maskin E, Farrell J (1989) Renegotiation in repeated games. Games Econom Behav 1:327–360

Rosati FC (1996) Social security in a non-altruistic model with uncertainty and endogenous fertility. J Public Econ 60:283–294

Shubick M (1981) Society, land, love or money. J Econ Behav Organ 6:359–385

Sinn HW (1990) Korreferat zum Referat von K. Jaeger. In: Gahlen B, Hesse H, Ramser HJ (eds) Theorie und Politik der Sozialversicherung. Mohr-Siebeck, Tübingen

Acknowledgements

This paper has benefited from comments by Daniele Fabbri and Annalisa Luporini and from constructive criticism by two anonymous referees. The remaining errors are the author’s responsibility.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Responsible editor: Gil S. Epstein

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cigno, A. A constitutional theory of the family. J Popul Econ 19, 259–283 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-006-0062-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-006-0062-2

Keywords

- Families

- Self-enforcing constitutions

- Renegotiation-proofness

- Altruism

- Fertility

- Saving

- Transfers

- Attention

- Pensions

- Credit rationing