Abstract

The emergence of generative artificial intelligence, such as large language models and text-to-image models, has had a profound impact on society. The ability of these systems to simulate human capabilities such as text writing and image creation is radically redefining a wide range of practices, from artistic production to education. While there is no doubt that these innovations are beneficial to our lives, the pervasiveness of these technologies should not be underestimated, and raising increasingly pressing ethical questions that require a radical resemantization of certain notions traditionally ascribed to humans alone. Among these notions, that of technological intentionality plays a central role. With regard to this notion, this paper first aims to highlight what we propose to define in terms of the intentionality gap, whereby, insofar as, currently, (1) it is increasingly difficult to assign responsibility for the actions performed by AI systems to humans, as these systems are increasingly autonomous, and (2) it is increasingly complex to reconstruct the reasoning behind the results they produce as we move away from good old fashioned AI; it is now even more difficult to trace the intentionality of AI systems back to the intentions of the developers and end users. This gap between human and technological intentionality requires a revision of the concept of intentionality; to this end, we propose here to assign preter-intentional behavior to generative AI. We use this term to highlight how AI intentionality both incorporates and transcends human intentionality; i.e., it goes beyond (preter) human intentionality while being linked to it. To show the merits of this notion, we first rule out the possibility that such preter-intentionality is merely an unintended consequence and then explore its nature by comparing it with some paradigmatic notions of technological intentionality present in the wider debate on the moral (and technological) status of AI.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Responsibility gap, knowledge gap and intentionality gap

The emergence of generative artificial intelligence, such as large language models and text-to-image models, has had a profound impact on our society. The ability of these systems to simulate human capabilities such as text writing and image creation is radically redefining a wide range of practices, from artistic production (see, e.g., Zhou & Lee 2024) to education (see, e.g., Akinwalere & Ivanov 2022). While there is no doubt that these innovations are beneficial to our lives, the pervasiveness of these technologies should not be underestimated, and raising increasingly pressing ethical questions that require a radical resemantization of certain notions traditionally ascribed to humans alone.

One example of this need is the so-called responsibility gap (Matthias 2004), which calls for a redefinition of the notion of responsibility (see, e.g., Santoni de Sio & Mecacci 2021; Faroldi 2021; Gunkel 2020; Loh & Loh 2017; Hanson 2009). The more autonomous machines are, the less human intervention is needed, and the more difficult it is to identify who or what is responsible for the actions of AI systems. Is the image produced by an AI art generator the work of the user who entered the prompt or of the generative AI (Terzidis et al. 2023)? Should AlphaGo’s victory be attributed to AlphaGo or to its developers (Gunkel 2020)? In what sense can we say that AI is responsible or quasi-responsible (Stahl 2006) for its actions?

This responsibility gap, according to which it is difficult to find a criterion for the redistribution of responsibility between human agents and AI systems, is linked to the so-called knowledge gap (Coeckelbergh 2022b: 123–124), which means that we are increasingly less aware of how an AI system arrives at a certain result. The algorithmic opacityFootnote 1 from which the latest machine learning models are affected does not allow us to rely on them in particularly sensitive fields, such as the legal (see, e.g., Funke 2022) and medical fields (see, e.g., Ratti & Graves 2022; Herzog 2019). Therefore, explainable AI (XAI) (Gunning et al. 2019) is currently being proposed for reconstructing reasoning followed by the AI in the decision-making process. However, the proposed techniques (e.g., causal machine learning; for this approach, see, e.g., Kaddour et al. 2022) do not always succeed in opening the black box.

Added to this scenario, characterized by responsibility and knowledge gaps, is what we propose to define in terms of the intentionality gap, which is closely linked to the first two. Insofar as (1) it is increasingly difficult to assign responsibility for the actions performed by AI systems to humans, since these systems are increasingly autonomous, and (2) it is increasingly complex to reconstruct the reasoning behind the results obtained by them the further we move away from good old fashioned AI (Haugeland 1985); it is now even more difficult to trace the intentionality of AI systems back to the intentions of developers and end users. In other words, whereas in the past, symbolic AI, that is, explicit, rule-based AI, merely incorporated the intentions of developers and users, machine learning and deep learning models now have abilities that were not present in previous models and that convey intentionality that is no longer simply derived. For example, the image produced by a text-to-image model is not predictable by the artist and is not the mere result of the prompt he or she entered. Similarly, LLMs have emergent abilities (Wei et al. 2022), such as the capacity for moral self-correction (Ganguli et al. 2023), that are certainly not part of the designed functions. In this sense, we are producing AI systems that we know, right from the design stage, will be beyond our intentions and knowledge.

In this paper, we intend to discuss this technological intentionality that surpasses human intentionality to show that such intentionality is a congenital element of generative AI models. Once we have ruled out the possibility that such intentionality is a mere unintended consequence (Sect. 2), we intend to explore its nature by comparing it with some paradigmatic notions of technological intentionality present in the broad debate on the moral (and technological) status of AI (Sect. 3). Finally, we propose to define the type of intentionality with which generative AI is endowed in terms of preter-intentionality to better express the surplus nature of the technological intentionality embedded in such models with respect to human intentionality (Sect. 4).

2 Intentionality in generative AI, design fallacy and unintended consequences

To delimit the topic of our paper, it should be noted that technological intentionality is not merely an unintended consequence, in the sense of an unforeseen effect of the use of technology (Tenner 1996). Indeed, in the field of generative AI, we design machines that intentionally go beyond our intentions, i.e., their behavior is not, from the design stage, completely determined by the programme and predictable by the designers (see, e.g., Douglas Heaven 2024). Although it is human beings who assign a goal to the system, designers do not, in some cases, have sufficient knowledge of how the system will realize it and how it will interact with the environment to achieve it and thus of the decisions it will make (Mittelstadt 2016). This nondeterministic character of AI differentiates it from any simple tool, such as a hammer, which can certainly be used for purposes other than those planned; however, such misuses are nothing more than violations of the use planFootnote 2 (see Vermaas et al. 2022) and are merely unintended consequences. In the use plan of generative AI, we have instead non-deterministically characterized outputs that, through random techniques, give intentionally unpredictable results, which make generative AI an open machine (Simondon 2017) with respect to the environment. In fact, only the AI system is designed in such a way as to function in excess of designers’ intentions from the outset. Thus, it is not just a matter of asserting, as Ihde does, that “all technologies”, including AI, “display ambiguous, multistable possibilities” with respect to uses, cultural embeddedness, and politics, and that it is consequently a fallacy to reduce all the functions of technologies to the designer’s intentions (Ihde 2002: 106). Rather, it is a matter of recognizing that generative AI possesses a congenital preter-intentional character, in the sense of going beyond the human intentions of both users and designers, and this surplus is an expected consequence. In fact, the various forms of generative AI are endowed with the capacity for machine learning, i.e., to learn from data and provide original outputs (a text, an image or a video), which intentionally do not have to simply reproduce the data provided, nor do they have to be reducible to the mere intention of the designers or users. In this sense, taking up one of Simondon’s ideas, it can be observed that the perfecting of machines does not correspond to complete automatism or complete predetermination but rather to the fact that the functioning of a machine contains a certain margin of indetermination (Simondon 2017). This margin allows the machine to better respond to input and interact with the environment. By virtue of this indeterminacy or incomplete determinacy, we can develop an AI that solves a problem in an unexpected way (Terzidis 2023: 1718), i.e., without knowing in advance how it will handle the inputs and what the role of each input will be in the process of generating the output (Mittelstadt 2016: 4). Thus, while AI systems are allocentered because we humans define their goals, they are autonomous and not heteronomous since they have an undetermined character and give themselves rules (Terzidis 2023: 1720).

We shall now examine some paradigmatic positions that, in the context of the debate on the moral (and technological) status of artificial intelligence, assign some kind of intentionality to AI systems. In relation to these positions, whose merits and limitations we highlight, we propose applying the notion of preter-intentionality to the behavior of generative AI, convinced that this notion accounts better than others for the peculiar dynamic that is established between human intentionality and technological intentionality in generative AI.

3 The problem of intentionality in artificial intelligence systems

In the debate about the moral status of artificial intelligence (see, e.g., Coeckelbergh 2020a: 47–62; Llorca Albareda et al. 2023; Redaelli 2023a), the question of whether technical artifacts have some form of intentionality (or not) that would allow them to be considered part of the moral world (or excluded from it) plays a far from marginal role. In fact, the concept of intentionality constitutes a cornerstone in the construction of the notion of moral agency, as evidenced, inter alia, by the fact that, in many cases, technological objects have been excluded from the field of ethics precisely because they lack intentionality, to which the notions of autonomy and responsibility are traditionally linked.

In contrast to these positions, there is currently a tendency to increasingly attribute some form of intentionality to AI systems. More specifically, these systems, like more complex technologies, are recognized as having what is defined in terms of technological intentionality (see, e.g., Mykhailov & Liberati 2023) understood from time to time as functionality (Johnson 2006), directivity (Verbeek 2011), or intention to act in a broad sense (Sullins 2006)—just to name a few meanings attributed to it.Footnote 3 Hence, as is already evident from these hints, under the aegis of this term hides a quagmire of ideas that cannot readily be recomposed into a unitary scheme. This polysemy, to which the term intentionality has always been linked, has the effect of multiplying the positions in the debate on the moral status of artificial intelligence. In fact, these positions, while appealing to some form of intentionality, do not seem to agree on what is meant by this term.

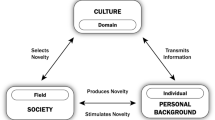

Despite the complexity of this scenario, one can recognize certain paradigmatic positions that invest the moral status of AI technologies in relation to the notion of intentionality. The first, represented by Deborah Johnson, tends to identify computer systems and AI as mere extensions of humans (Johnson 2006) or surrogate agents (Johnson and Powers 2008; Johnson & Noorman 2014), reducing technological intentionality to human intentionality. In this case, the intentionality of the system (computers, robots, AI) emerges from the intricate network of relationships involving the intentionality of programmers and users, where the former is, so to speak, embedded in the system, while the latter provides the input for the system’s intentionality to be activated. Such systems, in fact, incorporate the intentionality of users and designers into their own intentionality, which is related to their functionality (Johnson 2006: 201), thus forming a triad of intentionality that is at work in technologies. The intentionality of the system is, therefore, ultimately identifiable through the ability to produce output (the resulting behavior) from input data and is thus given by the union of the intentionality of the designers with that of the users. From this perspective, the unexpected consequences produced by computer systems and a certain nondeterministic character with which the computer is endowed are, according to Johnson, traced back to human beings and their inability to foresee the outcomes; i.e., they are part of risky behavior (Johnson 2006: 203–204). Therefore, for Johnson, the artificial agent is nothing more than a surrogate agent for humans (Johnson & Powers 2008; Johnson & Noorman 2014), doing the human interests delegated to it.

It should be noted that this position, in addition to being accused of instrumentalism and anthropocentrism (Gunkel 2017: 68), does not seem to take into account the behavior of certain technologies such as machine learning (Redaelli 2023a), which can, for example, lead AI systems to ‘disembed’ the values embedded in them or to embody new ones (Umbrello and van de Poel 2021), a behavior that is difficult to explain in terms of human–machine relations. In other words, such phenomena show that not all aspects and the operations of generative AI can be traced back to the intentions of the humans who implemented them.

Close to this position, which recalls the notion of a surrogate agent, is the decide-to-delegate model, in which “humans should retain the power to decide which decisions to take” (Floridi & Cowls 2019) and limit the autonomy of artificial agents. However, as also observed by Terzidis et al. (2023), once we humans delegate tasks to machines, they can produce outcomes that go beyond the designers' intentions, and it is difficult to maintain control over their decisions. In fact, the output of an AI is not deterministically characterized, and particularly in the presence of dropout techniques (Srivastava et al. 2014), the output is difficult to predict. Therefore, the decide-to-delegate model seems to disregard the peculiar intentionality of AI systems and their generativity.

To account for this generativity, this time in the field of digital art and not in the field of morality, Terzidis et al. (2023) introduce the notion of “unintentional intentionality”, ascribing to the output of the AI system an intention unrelated to the developers’ own intent. More precisely, the authors differentiate the verb ‘to intend’ from ‘intent’ as a resulting noun and associate intention not with the source but with the outcome itself (Terzidis et al. 2023: 1720). In this sense, they recognize an intent to the outcome without having to assign an intention to the AI system. This allows them to ascribe to the artistic outcome of an AI system an intention beyond the intentionality of the programmers.

This position, while appearing convincing in the context of digital art, where there are no exterior goals (Terzidis et al. 2023: 1716), is based exclusively on the outcome of the artistic process, openly leaving aside the process that leads to the outcome itself and thus failing to address the intermingling of human and intelligent systems behind the outcome. For this reason, the authors’ reflections are based exclusively on a consequentialist position that, while affirming that intentionality is not only human and can be assigned to a computational scheme, neglects investigating the technological intentionality of generative AI and thus the joint human‒machine action behind it.Footnote 4

A position that accounts for this joint action and the peculiar status of technological intentionality was developed in the postphenomenological field by Peter Paul Verbeek through the notion of composite intentionalityFootnote 5 (Verbeek 2011; 2008). Indeed, in this form of technological intentionality, “there is a central role for the ‘intentionalities’ or directedness of technological artifacts themselves, as they interact with the intentionalities of the human beings using these artifacts” (Verbeek 2011: 145). More precisely, in these words, in which the interaction between human and technological intentionality is emphasized, Verbeek points out that composite intentionality occurs when there is a synergy between technological intentionality, which is directed “toward ‘its’ world”, and human intentionality, which is “toward the result of this technological intentionality” (Verbeek 2011: 146). Thus, in the case of composite intentionality, “humans are directed here at the ways in which a technology is directed at the world” (Verbeek 2008: 393), where technology is a mediator between world and human.

In this regard, it is important to note that, in Verbeek’s eyes, with this type of technological intentionality, a reality is disclosed that is accessible only to such technologies and that, at the same time, through them, enters the human realm. In this sense, the author assigns this type of intentionality a dual function, representative and constructive. This means that this technological intentionality can not only represent reality but also constitute a reality that exists only for human intentionality if it is combined with technological intentionality (see, e.g., the images produced by AI art generators; on this point, see Redaelli 2023a).

As we have tried to show elsewhere (Redaelli 2023b), this notion of composite intentionality seems particularly suitable for explaining the intentionality present in AI systems. Such systems, in fact, present a technological intentionality understood as directivity that orients our action and thought. A directivity or intentionality that is indeed connected to the man who designs the machine and uses it but that, at the same time, presents an emerging character with respect to human intentionality, both that of the programmers and that of the users. This feature is linked to its capacity to structure new forms of reality (otherwise inaccessible to humans) and thus is ultimately related to its generativity. In this sense, machines’ intentionality goes beyond the triangulation highlighted by Johnson, as it is not reducible to mere functionality designed by humans and triggered by user input: artifacts incorporate human intentions and at the same time present “emergent forms of mediation” (Verbeek 2011: 127). Thus, artificial agents are not mere surrogates for the human agent but rather possess their own agency.

Although such a position is able to account for the intermingling of human and technological intentionality, where the latter is not a mere expression of the former, it encounters, according to some critics, numerous difficulties.Footnote 6 To summarize these objections, we may ask: in what sense should we understand the redistribution of intentionality between humans and technology? And again, in what way do the intentionality of man and that of the machine, which already incorporates human intentionality, form a composite intentionality? How are we able to understand this composite intentionality? These are just a few questions that remain unanswered by Verbeek.

To these unresolved problems is added the problem of the terminology employed by the philosopher, for which Coeckelbergh rightly observes that “some of these objections could be avoided if Verbeek would not use terms and phrases such the ‘morality of things’ and the ‘moral agency of things’ but stay with the claim that technologies mediate morality” (Cockelbergh 2020b: 67). The same can be said of the notion of technological intentionality, which in Verbeek seems to refer, according to some critics (see, e.g., Peterson and Spahn 2011), to a type of intention to act, which machines evidently lack.

Although such criticisms are mostly misunderstandings of Verbeek’s theses (see Redaelli 2022), it should be noted that the emergence of such critiques is due to a lack of vigilance towards language. Therefore, Coeckelbergh is right in emphasising the central role of language in our relationship with technologies. In particular, put in Wittgensteinian terms, a language game (Wittgenstein 1953) “is part of what we do and how we do things in a particular social context” (Coeckelbergh 2022a), which is why we need to pay more and more attention to the words we use in relation to new technologies. This transcendental character of language prompts us to attribute to technologies not so much a form of composite intentionality as a form of preter-intentionality. This notion, in our view, better renders the intertwining of man and machine referred to by the notion of composite intentionality, while at the same time avoiding the misunderstandings that can arise from Verbeek's use of the concept of intentionality.

4 Preter-intentionality

For the purpose of clarifying the meaning of the term preter-intentionality, it is worth recalling its Latin origin. This term, used in certain legal systems, for example, in Italian criminal law,Footnote 7 is, in fact, composed of the prefix preter ‘beyond’ and intendĕre in the sense of turning, tending.Footnote 8 The meaning it carries is therefore that of going beyond the intention of the agent (praeter intentionem) in the sense that the effect of an action may exceed the doer’s intention.Footnote 9

Apart from the legal use of this term, the meaning of going beyond the intention of the doer seems particularly apt to indicate the dynamic brought to light by composite intentionality, whereby the technological intentionality that emerges in human–AI interaction is not reducible to human intentionality but exceeds the human intentionality incorporated by the machine. In this sense, the term preter-intentionality seems to bring together two divergent instances in which the expressions technological and composite intentionality do not perfectly account.

First, the term has the merit of highlighting how the directing role played by intelligent systems in human experience is not entirely reducible to the human intention that intentionally brought it into being. In fact, as we have already observed, generative AI is intentionally developed to go beyond developers’ intentions. Regarding this peculiar status, the European Parliament speaks of a General Purpose AI system (GPAI), which “displays significant generality and is capable of competently performing a wide range of distinct tasks regardless of the way the model is placed on the market” (Artificial Intelligence Act 2024: 63). To account for the non-intentionality of certain applications of this type of generative AI, the term preter-intentionality seems particularly appropriate since designers intentionally develop systems whose functions are not specifically designed. In this sense, we propose to define, according to a circularity that is nevertheless not vicious, such preter-intentionality as congenital to such systems.

Second, the replacement of the term intentionality with preter-intentionality emphasizes how AI systems possess neither a conscious intention to act nor an intentionality in the broad sense. In this sense, the term preter-intentionality does not seem to lend itself to the criticism of attributing some form of intentionality to AI systems. In fact, if one were to consider the AI system and the human as a single actant, to use Latour's terminology (see, e.g., Latour 2005) or a composite or extended agent (Hanson 2009), one could evidently recognize a joint action that is both intentional (on the part of man) and unintentional (on the part of the AI system). In this sense, going beyond human intentions on the part of machines takes on a clear significance: it highlights the intentionally nonpredetermined character of the action of generative AI systems, an action that is not, however, a conscious action of the machine but rather gathers within it the conscious action of man.

Facing the two poles of intending and unintending is thus the preter-intentionality, by which term we wish to make room within generative AI for the recognition of a technological intentionality that

-

1)

is not a mere extension of the human (Johnson 2006);

-

2)

nor can it be reduced, as Verbeek (2011; 2008) does, to an intentionality whose compositionality is unclear;

-

3)

and is still not reducible to an intentionality linked exclusively to the outcome but not to the process leading to the outcome itself (Terzidis et al. 2023).

The example of the recurrent neural network model Sketch-RNN may help us to understand the notion of preter-intentionality. This Google experiment allows users to draw together with a recurrent neural network model called Sketch-RNN, which scribbles images based on the user’s initial drawing and choice of a model (cat, spider, garden, etc.). Once users start drawing an object, Sketch-RNN can continue drawing that object in many possible ways based on where users are left off (see Sketch-RNN Demos).

In this experiment, one can observe both human intentionality at the level of programming and input to initiate the system, as well as nonhuman preter-intentionality that starts from the human model and sketch but goes beyond both. In this sense, the outcome of the generative human–AI interaction—the image produced—exceeds the intentions of the human agents who designed and use such an AI: they cannot predict the outcome, and this unpredictability is expected since the system is required to produce an original sketch.

This example makes it clear that one cannot consider the mere result, as (Terzidis et al. 2023) do, without considering the process behind it, nor can one reduce it to a mere unexpected consequence. In fact, the result of a generative AI reflects the source, which is neither exclusively human nor exclusively technological but is given by the interaction between man and machine, in which the machine's action has a preter-intentional character that recalls its relationship with man and, at the same time, its surplus. This surplus is consciously pursued by designers with the help of ML algorithms, which can learn from the patterns and features present in the dataset and generate new images, texts and thus new results that correspond to the input parameters.

5 Conclusions

Our examination shows that the term preter-intentionality is particularly apt to refer to generative AI behaviour for the following reasons:

-

1)

Compared to the term intentionality, which in many cases seems to refer to a conscious intention to act, the term preter-intentionality refers to both the overcoming of the intentions of designers and users by generative AI and its dependence on them, leaving no room for misunderstanding that the term intentionality encounters.

-

2)

The term preter-intentionality is suitable for explaining the generativity of AI systems without having to assign an intentionality to them in the strict sense.

-

3)

The term preter-intentionality seems to respond to the challenges posed by what we have called the intentionality gap, whereby it is currently increasingly difficult to trace the behavior of AI systems back to human intentionality. In this sense, the term preter-intentionality highlights the human‒machine interaction from which the behavior of the AI system arises.

Notes

Algorithms “are opaque in the sense that if one is a recipient of the output of the algorithm (the classification decision), rarely does one have any concrete sense of how or why a particular classification has been arrived at from inputs’’ (Burrell 2016: 1).

Van de Poel defines the use plan in the following terms: “A use plan is a plan that describes how an artifact should be used to achieve certain goals or to fulfill its function. In other words, a use plan describes the proper use of a technical artifact, and that proper use will result (in the right context and with users with the right competences) in the artifact fulfilling its proper function” (Van de Poel 2020).

This tendency to attribute intentionality to AI systems is found not only in the philosophical field, but also in computer science. In this field, very recent studies confirm, by means of quantitative research, the presence of a certain intentionality in intelligent systems and attempt to clarify this concept. In this regard, see, with regard to reinforcement learning agents, above all the work of Córdoba et al. 2023; Ward et al. 2024.

In this sense, Terzidis et al. (2023) reduce the intention that is conveyed by the outcome to a mere unexpected consequence, whereas according to our proposal, it is an intended consequence in generative AI.

To better understand Verbeek’s proposal, it is necessary to observe that in Verbeek (2011) the author uses the expression composite intentionality in a twofold sense. On the one hand, the author, referring to a broad notion of composite intentionality, states that “intentionality is always a hybrid affair involving both human and nonhuman intentions or, better, ‘composite intentions’ with intentionality distributed among the human and nonhuman elements in human-technology-world relationships” (Verbeek 2011: 58). In this sense, a form of composite intentionality is at work in every human-technology relationship. On the other hand, Verbeek develops, in the same text, a, so to speak, narrow notion of composite intentionality, where technological intentionality plays a central role and human intentionality interacts with that of technology, forming a composite intentionality that does not merely perform a mediating function, but forms composite relations (Verbeek 2011: 140). In such relations, artificial intentionality is added to human intentionality. Despite this distinction, it is necessary to clarify that the narrow notion, to which we refer in this paper, evidently presupposes the broad notion of composite intentionality.

For an overview of the criticism levelled at Verbeek see Cockelbergh (2020).

The Italian Penal Code contains provisions on culpability, and mentions in article 42 intentional, preterintentional,

and culpable commission of a crime. With regard to the legal sphere, it should be pointed out that the use of the term ‘preter-intentionality’ raises the question of whether liability should be attributed to artificial agents. Although the issue is not addressed in this paper, important considerations are made in relation to criminal law by Faroldi 2021.

“Beyond or additional to what is intended” (“Preterintentional”, Oxford English Dictionary).

In the philosophical field, the term preter-intentionality is employed by Di Martino (2017) to explain the feedback effects of technologies on humans and the processes of human subjectivization.

References

Akinwalere SN, Ivanov V (2022) Artificial intelligence in higher education: challenges and opportunities. Border Cross. https://doi.org/10.33182/bc.v12i1.2015

Artificial Intelligence Act 2024. European Parliament legislative resolution of 13 March 2024 on the proposal for a regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on laying down harmonized rules on Artificial Intelligence (Artificial Intelligence Act) and amending certain Union Legislative Acts (COM(2021)0206 – C9–0146/2021 – 2021/0106(COD))

Burrell J (2016) How the machine 'thinks': understanding opacity in machine learning algorithms. Big Data Soc 3(1):1–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053951715622512

Coeckelbergh M (2020a) AI Ethics. MIT press, Cambridge, Massachusetts

Coeckelbergh M (2020b) Introduction to Philosophy of Technology. Oxford University Press, New York

Coeckelbergh M (2022a) Earth, technology, language: a contribution to holistic and transcendental revisions after the artifactual turn. Found Sci 27:259–270. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10699-020-09730-9

Coeckelbergh M (2022b) Robot Ethics. MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts

Córdoba FC, Judson S, Antonopoulos T, Bjørner K, Shoemaker N, Shapiro SJ, Piskac R, Könighofer B (2023) Analyzing Intentional Behavior in Autonomous Agents under Uncertainty. In: Proceedings of the Thirty-Second International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence. https://doi.org/10.24963/ijcai.2023/42

Di Martino C (2017) Viventi umani e non umani. Cortina, Milano

Douglas Heaven W (2024) Large Language Models can do jaw-dropping things. But nobody knows exactly why. Mit Technology Review. https://www.technologyreview.com/2024/03/04/1089403/large-language-models-amazing-but-nobody-knows-why/. Accessed 22 March 2024

Faroldi FLG (2021) Considerazioni filosofiche sullo statuto normativo di agenti artificiali superintelligenti. Revista Iustitia

Floridi L, Cowls J (2019) A unified framework of five principles for AI in society. Harvard Data Sci Rev. https://doi.org/10.1162/99608f92.8cd550d1

Funke A (2022) Ich bin dein Richter. Sind KI-basierte Gerichtsentscheidungen rechtlich denkbar? In: Adrian A, Kohlhase M, Evert S, Zwickel M, (eds) Digitalisierung von Zivilprozess und Rechtsdurchsetzung. Duncker & Humblot, Berlin

Ganguli D, Askell A et al. (2023) The Capacity for Moral Self-Correction in Large Language Models. arXiv:2302.07459v2 [cs. CL] 18 Feb 2023

Gunkel DJ (2017) The Machine Question: Critical Perspectives on AI, Robots, and Ethics. The MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts

Gunkel DJ (2020) Mind the gap: responsible robotics and the problem of responsibility. Ethics Inf Technol 22:307–320. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10676-017-9428-2

Gunning D, Stefik M, Choi J, Miller T, Stumpf S, Yang GZ (2019) XAI-Explainable artificial intelligence. Sci Robot. https://doi.org/10.1126/scirobotics.aay7120

Hanson FA (2009) Beyond the skin bag: on the moral responsibility of extended agencies. Ethics Inf Technol 11:91–99. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10676-009-9184-z

Haugeland J (1985) Artificial Intelligence: The very Idea. The MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts

Herzog C (2019) Technological Opacity of Machine Learning in Healthcare. In: Proceedings of the Weizenbaum Conference 2019 “Challenges of Digital Inequality - Digital Education, Digital Work, Digital Life”, Berlin, pp 1–9

Ihde D (2002) Bodies in Technology. University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis-London

Johnson DG (2006) Computer systems: moral entities but not moral agents. Ethics Inf Technol 8:195–204. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10676-006-9111-5

Johnson DG, Noorman M (2014) Artefactual agency and artefactual moral agency. In: Kroes P, Verbeek PP (eds) The moral status of technical artefacts. Springer, Dordrecht, pp 143–158

Johnson DG, Powers T (2008) Computers as surrogate agents. In: van den Hoven J, Weckert J (eds) Information technology and moral philosophy. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, pp 251–269

Kaddour J, Lynch A, Liu Q, Kusner MJ, Silva R (2022) Causal Machine Learning: A Survey and Open Problems, arXiv:2206.15475

Latour B (2005) Reassembling the social: an introduction to actor-network-theory. Oxford University Press, New York

Llorca Albareda J, García P, Lara F (2023) The moral status of AI entities. In: Lara F, Deckers J (eds) Ethics of artificial intelligence. The International Library of Ethics, Law and Technology, Springer, Cham, pp 59–83

Loh, W, Loh, J (2017) Autonomy and responsibility in hybrid systems: the example of autonomous cars. In: Lin P, Jenkins R, Abney K (eds) Robot ethics 2.0: from autonomous cars to artificial intelligence. Oxford University Press, New York, pp 35–50

Matthias A (2004) The responsibility gap: ascribing responsibility for the actions of learning automata. Ethics Inf Technol 6(3):175–183. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10676-004-3422-1

Mittelstadt BD, Allo P, Taddeo M, Wachter S, Floridi L (2016) The ethics of algorithms: Mapping the debate. Big Data Soc.

Mykhailov D, Liberati N (2023) A study of technological intentionality in C++ and generative adversarial model: phenomenological and postphenomenological perspectives. Found Sci 28:841–857. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10699-022-09833-5

Peterson M, Spahn A (2011) Can technological artifacts be moral agents? Sci Eng Ethics 17:411–424. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-010-9241-3

Ratti E, Graves M (2022) Explainable machine learning practices: opening another black box for reliable medical AI. AI Ethics 2:801–814. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43681-022-00141-z

Redaelli R (2022) Composite intentionality and responsibility for an ethics of artificial intelligence. Scenari 17:159–176. https://doi.org/10.7413/24208914133

Redaelli R (2023a) Different approaches to the moral status of AI: a comparative analysis of paradigmatic trends in Science and Technology Studies. Discov Artif Intell 3:25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s44163-023-00076-2

Redaelli R (2023b) From tool to mediator. A postphenomenological approach to artificial intelligence. In: LM Possati (ed) Humanizing artificial intelligence. Psychoanalysis and the problem of control, De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston, pp 95–110

Santoni de Sio F, Mecacci G (2021) Four responsibility gaps with artificial intelligence: why they matter and how to address them. Philos Technol 34:1057–1084. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13347-021-00450-x

Simondon G (2017) On the Mode of Existence of Technical Objects. Univocal, Minneapolis

Srivastava N, Hinton G, Krizhevsky A, Sutskever I, Salakhutdinov R (2014) Dropout: a simple way to prevent neural networks from overfitting. J Mach Learn Res 15:1929–1958

Stahl BC (2006) Responsible computers? A case for ascribing quasi-responsibility to computers independent of personhood or agency. Ethics Inf Technol 8:205–213. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10676-006-9112-4

Sullins JP (2006) When is a robot a moral agent? Inter Rev Inform Ethics 6:23–30

Tenner E (1996) Why things bite back: technology and the revenge of unintended consequences. Vintage Books, New York

Terzidis K, Fabrocini F, Lee H (2023) Unintentional intentionality: art and design in the age of artificial intelligence. AI & Soc 38:1715–1724. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-021-01378-8

Umbrello S, van de Poel I (2021) Mapping value sensitive design onto AI for social good principles. AI Ethics 1:283–296. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43681-021-00038-3

van de Poel I (2020) Embedding values in artificial intelligence (AI) systems. Mind Mach 30:385–409. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11023-020-09537-4

Verbeek PP (2008) Cyborg intentionality: Rethinking the phenomenology of human-technology relations. Phenomenol Cogn Sci 7(3):387–395. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11097-008-9099-x

Verbeek PP (2011) Moralizing technology: understanding and designing the morality of things. University of Chicago Press, Chicago and London

Vermaas P, Kroes P, van de Poel I, Franssen M, Houkes W (2022) A philosophy of technology. From technical artefacts to sociotechnical system, Springer, Cham

Ward FR, MacDermott M, Belardinelli F, Toni F, Everitt T (2024) The reasons that agents act: Intention and instrumental goals. In: Proceedings of the 23rd International Conference on autonomous agents and multiagent systems (AAMAS '24). International Foundation for Autonomous Agents and Multiagent Systems, Richland, SC, 1901–1909

Wei J et al. (2022) Emergent Abilities of Large Language Models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2206.07682

Wittgenstein L (1953) Philosophical Investigations, Revised 4th ed. GEM Anscombe, PMS Hacker, J. Schulte, Trans. Wiley, Malden, MA

Zhou E, Lee D (2024) Generative artificial intelligence, human creativity, and art. PNAS Nexus. https://doi.org/10.1093/pnasnexus/pgae052

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Milano within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author declares no conflict of interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Redaelli, R. Intentionality gap and preter-intentionality in generative artificial intelligence. AI & Soc (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-024-02007-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-024-02007-w