Abstract

The complex relationships between humans and AI-empowered machines have created and inspired new products and services as well as controversial debates, fiction and entertainment, and last but not least, a striving and vital field of research. The (theoretical) convergence between the two categories of entities has created stimulating concepts and theories in the past, such as the uncanny valley, machinization of humans through datafication, or humanization of machines, known as anthropomorphization. In this article, we identify a new gap in the relational interaction between humans and AI triggered by commercial interests, making use of AI through advertisement, marketing, and corporate communications. Our scope is to broaden the field of AI and society by adding the business-society-nexus. Thus, we build on existing research streams of machinewashing and the analogous phenomenon of greenwashing to theorize about the humanwashing of AI-enabled machines as a specific anthropomorphization notion. In this way, the article offers a contribution to the anthropomorphization literature conceptualizing humanwashing as a deceptive use of AI-enabled machines (AIEMs) aimed at intentionally or unintentionally misleading organizational stakeholders and the broader public about the true capabilities that AIEMs possess.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Recent advancements in AI systems have triggered a set of innovative products, services, and business models while fueling controversial public and academic debates on the convergence of humans and machines (Vogt 2021). For several years, the uncanny valley theory has been at the center of the convergence discussion when studying people’s responses to humanlike robots (Gahrn-Andersen 2020; Mori et al. 2012). More recently, new and related theory angles have joined the debate, looking at the machinization of humans through different forms of posthuman datafication (Bolin and Andersson Schwarz 2015) and the humanization of machines, known as “anthropomorphization”(Coeckelbergh 2021; Riva et al. 2015). Against this background of relational interaction between humans and AI-enabled machines (AIEM), this article focuses on another evolving gap triggered by commercial advertisement, marketing, and corporate communication of AI-powered robots. Thus, this article strives to broaden the scope of current discussions in AI and society by adding the business-society-nexus and the notion of “humanwashing of machines.” In analogy to the established greenwashing concept in the environmental domain, humanwashing or machine washing may be seen as a means to mislead organizational stakeholders and the broader public (Becker-Olsen and Potucek 2013; Berrone et al. 2017; Obradovich et al. 2019). Thus, we conceptualize humanwashing as the deceptive use of AIEM to mislead organizational stakeholders and the broader public about the true capabilities that the machines possess (Becker-Olsen and Potucek 2013; Obradovich et al. 2019; Parviainen and Coeckelbergh 2020; Seele and Schultz 2022). In this way, we shed light on the power asymmetries involved in the anthropomorphization of robots, particularly in relation to robots without a clear social use case. By staging robots as humanlike, corporations can build on their knowledge advantage and let observers believe in unrealistic robot capacities (e.g., artificial general intelligence) or distract observers from the true capacities that a robot may perform (e.g., military use cases). Thus, we argue that the anthropomorphization of robots can be used as a strategic means that draws the observers’ attention away from the potential adverse or harmful impacts of AIEMs while creating unrealistic perceptions of harmless, humanlike behavior. Such asymmetric communication about AIEMs' factual capabilities is particularly problematic for dual-use robots that can serve military purposes. From a practical perspective, the humanwashing of AIEMs requires the attention of practitioners to address the power asymmetries involved in anthropomorphization and take responsibility for misleading meanings that can evolve.

2 Human–robot convergence and interaction

The convergence of humans and AI-enabled machines (AIEM) has been the focus of different angles of AI and society research, including posthumanism(Nath and Manna 2021) and the more design-oriented field of Human–robot interaction (HRI), encompassing “almost all situations where humans and robots are co-located”(Billard and Grollman 2012, p. 1474). For several years, the uncanny valley theory has been at the center of the convergence discussion studying people’s response to humanlike robots (Draude 2011; Gahrn-Andersen 2020; Mori et al. 2012). More recently addition theoretical angles have joined the AI and society debate, looking at the machinization of humans through different forms of posthuman datafication(Bolin and Andersson Schwarz 2015; Nath and Manna 2021) and the humanizationFootnote 1 of machines, known as “anthropomorphization”(Coeckelbergh 2021; Riva et al. 2015). Making robots appear more humanlike to enhance human–robot interaction and increase the robot’s acceptance has been a central goal in developing AIEMs. This is frequently attributed to the human preference for anthropocentric interactions, which is to say that “if people mindlessly apply human–human interaction rules with nonhuman beings and objects, then humanizing robots will result in more natural and efficient HRIs” (Giger et al. 2019, p. 112).

The latter concept is related to the “Theory of Mind,” which refers to our tendency of attributing beliefs, mental states, or emotions to nonhuman agents, meaning that, regardless of the exterior appearance of an object, we tend to apply our social norms to our interaction with it (Giger et al. 2019). An example of such a tendency is the ELIZA effect, when humans attribute human traits to robots, including empathy and the tendency to punish robots when they make mistakes (S. Y. Kim et al. 2019b). Consequently, humanizing robots can increase their societal acceptance and are not limited to their physical appearance. According to Giger et al. (2019), the humanization of social robots is “the effort to make robots that more closely mimic human appearance and behavior, including the display of humanlike cognitive and emotional states” (Giger et al. 2019, p. 111). Thus, anthropomorphization is not strictly linked to robot’s exterior appearance, but it is also a matter of how the robot is designed to act and interact with humans, which should overall recall a peer interaction.

As shown above, a robot’s design and presentation can increase human–robot collaboration, foster robot adoption, and ultimately the societal acceptance of robots (Esterwood et al. 2021). However, some obstacles can prevent such positive outcomes as human perceptions of robot anthropomorphization are not always favorable. The interaction with social robots can make humans sense a “loss of distinctiveness,” “loss of human uniqueness,” and feelings of eeriness may arise (Giger et al. 2019). Feelings of eeriness relate to the uncanny valley effect. Robots designed to look like humans can stimulate a particular reaction of revulsion if robots fail to completely resemble humans (Draude 2011; Mori et al. 2012). As Mori (2012) notes, when giving robots a humanlike appearance, our sense of affinity towards the robot increases. However, when the design makes us realize that the robot is actually artificial, an “eerie sensation” can rise (Mori et al. 2012). Mori et al. (2012, p. 100) explain this as “a form of instinct that protects us from proximal, rather than distal, sources of danger.” In a recent study by Kim et al. (2020), the uncanny valley effect was re-confirmed with static images of 251 robots presented to participants. In addition, the study revealed a “second” uncanny valley for those robots that had little physical resemblance with humans, suggesting that “even when the robots have a low or moderate resemblance with humans, if there are perceptual mismatches between different appearance dimensions in the robots, people may perceive them as uncanny” (Kim et al. 2020, pp. 3–4). However, the identified effect can be different for animated images. Mori writes that movement is fundamental as “its presence changes the shape of the uncanny valley graph by amplifying the peaks and valleys” (Mori et al. 2012, p. 99). Consequently, as soon as the robot starts moving humanlike, we tend to feel an affinity for the robot.

Overall, previous research shows that the design and presentation of robots as humanlike plays a crucial role in fostering human–robot interaction and generating social acceptance of robots (Esterwood et al. 2021). Even though it is challenging and risks the robot “falling” into the uncanny valley or creating unease among observers, many companies rely on different forms of anthropomorphization in designing and promoting their robots. Recent literature on anthropomorphism in social robotics helps shed light on this topic.

3 Approaches to anthropomorphism

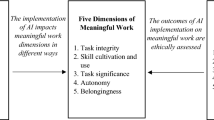

In its strictest sense, the term ‘anthropomorphism’ refers to a type of bias or an error that entails the tendency to attribute human-like characteristics, such as intuition, emotions, and appearance, to objects or animals (Dacey 2017). Recent literature describes different approaches towards anthropomorphism, which may range from: (1) perceiving AIEMs as mere tools to (2) embracing them as humanlike agents, and (3) a third position conciliating between the previous extremes,focusing on AIEMs as cognitive systems, jointly formed in the business-society nexus (2019). In the following, each approach will be discussed in further detail.

3.1 AIEMs as tools

This approach perceives AIEMs as tools or instruments created to fulfill human purposes (2019). When a robot is perceived as a tool, it is usually not designed to adapt to changes in the world. It has the purpose of performing either limited or specialized functions (Hauser et al. 2021). From this perspective, recent research underlines anthropomorphism as a crucial factor in people’s willingness to adopt, use, and form positive or negative attitudes towards AIEMs (Li and Suh 2021). It has been shown that consumers prefer robotic systems featuring humanlike characteristics and feelings, such as humor or empathy, over systems with equal capacities but a lack of human likeness(Rzepka and Berger 2018). AIEMs equipped with human characteristics increase trust, reduce stress, foster likeability, and thus, increase their adoption and use(Paiva et al. 2017). Moreover, if such robotic systems make mistakes, consumers are more likely to forgive them than non-anthropomorphized systems(Yam et al. 2021). However, anthropomorphism can also lead to negative attitudes and a refusal of AIEMs (Rzepka and Berger 2018; Kim et al. 2019a; Gursoy et al. 2019). High anthropomorphic appearance can be perceived as a threat to human identity. The robot appears as a source of danger (Lu et al. 2019). Consequently, the instrumental approach toward anthropomorphism strives to overcome such challenges by augmenting AIEMs utility (Lu et al. 2019). This instrumental focus on the question of how to best fulfill the desired purpose of AIEMs has been criticized for not sufficiently accounting for the broader societal embedding: scientists “know that the robot is just a tool, but nevertheless when we interact with the robot our psychology (the psychology of users) leads us to perceive the robot as a kind of person” (Coeckelbergh 2021, p. 3). Consequently, treating AIEMs as instrumental tools overlooks the unintended outcomes that naturally evolve with human–machine interactions and the societal embeddedness of humanlike AIEMs.

3.2 AIEM as humanlike agents

The second approach towards anthropomorphism is characterized by the objective of producing a kind of human replica (Giger et al. 2019, p. 112). This involves embracing “robots as quasi-persons and “others,” which is to say that social robots should be part of the network of humans and nonhumans (Coeckelbergh 2021). AIEMs are viewed as humanlike agents that may adapt to social situations independently. Therefore, while in the first approach, humanization is considered a means to best fulfill the AIEMs specific design purpose, in the second case, the replication of human interaction is at the center of anthropomorphization. This approach entails a much broader understanding of AIEMs that goes far beyond the previously described instrumental perspective of AIEM as a tool or thing in contrast to humans. Quite the contrary, perceiving AIEMs as humanlike agents stretches the boundaries between the human and nonhuman, deconstructing the conception of humanness in light of post- and transhuman futures (Nath and Manna 2021; Baelo-Allué and Calvo-Pascual 2021; Sorgner 2022; Hofkirchner and Kreowski 2021). Thus, conceptions of posthumanism and transhumanism provide a wider perspective on human-technology evolution, where anthropomorphization follows the idea to make AIEMs increasingly humanlike, including them as social actors in all societal spheres (Hofkirchner and Kreowski 2021). However, conceptions of AIEMs as humanlike agents often overlook the fact that human designers remain decisive, raising doubt about whether robots may ultimately become others or nonhumans (Nath and Manna 2021). Therefore, while the first view tends to overlook the fact that there is a relation between humans and technology, the second is limited in the understanding that AIEMs may never become completely external beings because of their origin.

3.3 AIEM as joint cognitive systems

Going beyond the previously depicted approaches, a third perspective strives to reconcile the previous extremes. From this vein, AIEMs are perceived as a joint cognitive system, treating them as part of the social nexus. Different from the views introduced before, the focus is set on the relation between robots and humans and their social embedding relating to the notion of AI and society. The third approach allows for a critical view of anthropomorphization. Coeckelbergh (2021) recently outlined five elements characterizing this approach towards anthropomorphization: (a) The first characteristic regards the fact that robots are designed by humans. They will never be totally other since they contribute to shaping our goals which makes them already part of our social sphere with no need of bringing them into it. (b) The second characteristic regards robots' linguistic and social construction. Indeed, “humans do not only materially create robots but also (during development, use, and interaction) “construct” them by means of language and in social relations, which must be presupposed when we think about these robots and interact with them” (Coeckelbergh 2021, p. 6). As Giger et al. (2019) explain, when a robot is anthropomorphized, physical characteristics, like gender and race, are attributed to it. In this way, the meaning of the AIET is co-shaped (2021), underlining its profound embedding in the socio-cultural environment: “By giving it a particular name, users may also tap into an entire culture of naming and gendering” (Coeckelbergh 2021, p. 7). (c) The third characteristic regards another aspect of relationality: AIETs embeddedness in cultural wholes. Indeed, they are related to our “social practices and systems of meaning,” with the crucial point being that robots actually contribute to our meaning-making, and this is the case not only for social robots (Coeckelbergh 2021). (d) The fourth characteristic regards the lack of hermeneutic control. In fact, the meaning-making process is not always under complete control. Indeed, there is some unintended meaning generation when humans engage with other humans. Therefore, interactions with robots may also lead to unintended meaning generation. (d) The fifth characteristic—power—relates to social robots interacting with us and generating meaning (Coeckelbergh 2021). The latter has a social and political effect. This is because behind each robot lies a company. Even if it is not always the case, there could be an underlying manipulation or exploitation in the anthropomorphization (Hauser et al. 2021). This paper particularly builds on the corporate power characteristic to discuss the anthropomorphization of robots in social relations.

3.4 Robots as powerful instruments-in-relation: corporate marketing and the notion of greenwashing

This article addresses the relational interaction between human actors and AI in light of powerful commercial interests underlying the staging of AIEM in advertisements, marketing, and corporate communication (Tollon and Naidoo 2021). Thus, particularly building on the power characteristic of Coeckelbergh’s (2021) anthropomorphization conception. What remains hidden behind the robot’s mask or performance as other, or friend, are the actual capacities of the robot and the broader corporate power relations (Coeckelbergh 2021; Parviainen and Coeckelbergh 2020). Thus, behind the marketing veil, corporate interests tap into people’s psychological biases when presenting AIEM machines in advertisements and social media campaigns. Asymmetry of information is at the core of this phenomenon since only one party—the corporation—has the power of complete awareness of the state of reality. Connelly et al. (2011, p. 42) suggest two crucial asymmetry dimensions in this regard “information about quality and information about intent.” The first dimension relates to information asymmetry because an observer lacks full awareness of the other party, as in the case of corporate stakeholders being unaware of modern robots' actual capabilities (Connelly et al. 2011). The second dimension of information asymmetry deals with an observer’s concern about the other party’s behavioral intentions, which, in the case of robots, regards companies’ use of anthropomorphization as means that exploits people’s psychological biases (Coeckelbergh 2021).

Corporations may intentionally or unintentionally create unrealistic perceptions of robotic capabilities. This may involve designing and presenting robots that closely resemble humans and create the impression of a “friend or other” equipped with artificial general intelligence (AGI). “[A]s AI technology becomes more sophisticated, this illusion of intelligence will become increasingly convincing” (Shanahan 2015). Although the latest generation of robots may feature some form of AI, they still present mere machines or tools “that can perform specific, often highly limited or specialized, functions” (Murphy 2019, p. 20). As Shanahan (2015) states, “none of this technology comes anywhere near human-level intelligence, and it is unlikely to approach it anytime soon.” On the other end of the spectrum, one may find AIEMs far more advanced than the benign andromorphic mask suggests. AIEMs may be built for dual-use security purposes or directly fall into the category of “killer robots,” aka lethal autonomous weapon systems (Davenport et al. 2020; Lauwaert 2021; Pitt et al. 2021). Although such AIEMs may generally target governmental customers, their harmless anthropomorphic design may nevertheless be promoted via corporate advertisement and social media campaigns, creating the impression of a friendly other. However, behind the anthropomorphic mask, they can be equipped with capabilities far more advanced than what the corporate marketing campaign may suggest (Hauser et al. 2021; Parviainen and Coeckelbergh 2020; Seele 2021; Seele and Schultz 2022). Consequently, from a corporate point of view, the anthropomorphic presentation of robots in commercials may be advantageous to create awareness for products and attract potential investors. However, this practice may lead to misconceptions, as observers come to false conclusions about the robots’ capabilities.

This corporate practice closely resembles what is known as greenwashing in the business-society nexus: “Greenwashing is a special case of ‘merely symbolic’ in which firms deliberately manipulate their communications and symbolic practices so as to build a ceremonial façade” (Bowen 2014, p. 33). Thus, analogous to greenwashing, the underlying asymmetry of information allows the robot company to exploit their knowledge advantage about their products, let observers believe in unrealistic robot capacities, or distract observers from the actual capabilities that the robot can perform (Becker-Olsen and Potucek 2013; Berrone et al. 2017; Obradovich et al. 2019; Parviainen and Coeckelbergh 2020; Seele and Schultz 2022). Critical observers have termed this corporate strategy as “humanwashing of robots,” which is “meant to create the surface illusion of likable or harmless humanlike behavior of intelligent machines to charm away adverse or harmful characteristics or perceptions” (Seele 2021).

4 From anthropomorphization to humanwashing?

Humanlike presentations of AIEMs are becoming a frequent sight in commercial advertisements and corporate communications. In this article, we strive to add a new perspective to the anthropomorphization literature by conceptualizing the deceptive portrayal of AIEMs. By drawing on existing approaches toward anthropomorphization—in particular, the notion of robots as powerful instruments in relation—we offer a business-society-oriented contribution that can assist in illuminating commercial interests in service robotics and underlying power relations (Coeckelbergh 2021; Tollon and Naidoo 2021). Thus, we conceptualize humanwashing as a deceptive use of AIEMs, aimed at intentionally or unintentionally misleading organizational stakeholders and the broader public about the true capabilities that AIEMs possess (Becker-Olsen and Potucek 2013; Berrone et al. 2017; Obradovich et al. 2019; Parviainen and Coeckelbergh 2020; Seele 2021; Seele and Schultz 2022).

AIEMs from Boston Dynamics can serve as an illustration of the power and information asymmetries related to humanwashing. Boston Dynamics is a privately held corporation founded by Marc Raibert in 1992 and started designing physical robots with the help of US military funding from the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) (Metz 2018). The involvement of past military funding poses questions on the true intent behind the commercial presentation of AIEMs, particularly when it comes to viral social media marketing presenting the companies’ robots as charming and friendly (Boston Dynamics 2020). A recent news article highlights this tension, discussing Boston Dynamics’s current (non-military) flagship robot Spot and an almost identical AIET from a competitor equipped with a gun (Vincent 2021). Boston Dynamics acknowledges its past military history labeling videos that feature robots developed with governmental aid in an attempt for transparency. However, such transparency in viral marketing constitutes rather an exception than the rule.

Companies have a knowledge advantage when it comes to anthropomorphizing robots promoted in corporate advertorials and marketing campaigns. Companies know exactly what AIEMs can perform and where their limits are. In contrast, as shown by the results above, observers tend to focus on the anthropomorphic mask, unaware of what lies behind it. What the public perceives is subject to corporate communication and what can be interpreted from it. Thus, anthropomorphization can be used as a tool that creates a “ceremonial façade” or veil that can hide corporate interests and power (Bowen 2014, p. 33). As Coeckelbergh (2021, p. 8) notes, “[s]ocial robotics may well present robots as “others” and “friends”; but behind the curtain (and actually not all that well-hidden), there may be manipulation, exploitation, and disciplining.”

Consequently, power and information asymmetries are crucial characteristics of the humanwashing of robots. Corporations can build on their knowledge advantage when staging robots as humanlike and let observers believe in unrealistic robot capacities, such as artificial general intelligence. “Sophia is not the first show robot to attain celebrity status. Yet accusations of hype and deception have proliferated about the misrepresentation of AI to public and policymakers alike” (Sharkey 2018). Further, anthropomorphization may distract observers from the actual capacities that the robot can perform, particularly considering dual-use or military capabilities (Davenport et al. 2020; Lauwaert 2021; Pitt et al. 2021; Seele and Schultz 2022). In this way, the corporation may evade critical public discussions about its products and responsibilities arising with their deployment (Lauwaert 2021; Nordström, 2021). Thus, humanwashing may also be seen as a form of intentional non-transparency that conceals AIEMs actual configurations (Innerarity 2021).

In sum, we argue that the anthropomorphization of robots can be used as a strategic means that builds on the power of information asymmetry to draw the observer’s attention away from unfavorable aspects that would spotlight corporate power and power relations and instead evokes unrealistic or misleading perceptions of harmless, humanlike behavior.

5 Conclusions, limitations, and future research

The potential convergence and complex relationship between humans and AIEMs will undoubtedly continue to fuel public and academic discussions as new and even more advanced robots and business models are introduced. In this article, we strived to add a new perspective to the recent discussions on anthropomorphization, considering the business-society-nexus with the notion of humanwashing AIEMs. Since limited attention has been paid to anthropomorphization and the particular phenomenon of humanwashing, we focused in this article on a conceptual discussion of the humanwashing phenomenon. This approach certainly comes with limitations attached, as only follow-up empirical research will allow for an in-depth study of how observers perceive the commercial presentation of AIEMs. Thus, further qualitative and quantitative research is necessary to expand on the insights from this article, opening different pathways for study. Given the continuous increase in online marketing and corporate communication featuring AIEMs, future research may focus on studying related social media streams considering user perceptions and how they may change over time. Another fruitful avenue for future research could use controlled experimental designs to gain insights into observer perceptions. In addition, in-depth analysis of perceptions via interviews and case study methods may be considered. As uncanny valley literature depicts, static and dynamic presentations of anthropomorphization may trigger different user perceptions (Gahrn-Andersen 2020; Mori et al. 2012; Seele and Schultz 2022). Consequently, future research can help to deepen the understanding of anthropomorphization and humanwashing, revealing observer perceptions.

Availability of data and material

Not applicable.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Notes

In this research, the words “humanization” and “anthropomorphization” will be used interchangeably to describe the act of designing and attributing humanlike appearance and behavior to robots.

References

Baelo-Allué S, Calvo-Pascual M (eds) (2021) Transhumanism and posthumanism in twenty-first century narrative. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003129813

Becker-Olsen K, Potucek S (2013) Greenwashing. Encyclopedia of corporate social responsibility. Springer, Berlin Heidelberg, pp 1318–1323. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-28036-8_104

Berrone P, Fosfuri A, Gelabert L (2017) Does Greenwashing Pay Off? Understanding the Relationship Between Environmental Actions and Environmental Legitimacy. J Bus Ethics 144(2):363–379. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2816-9

Billard A, Grollman D (2012) Human–robot interaction. Encyclopedia of the sciences of learning, vol 58. Springer US, pp 1474–1476. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-1428-6_760

Bolin G, Andersson Schwarz J (2015) Heuristics of the algorithm: big data, user interpretation and institutional translation. Big Data Soc 2(2):1–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053951715608406

Boston Dynamics (2020) Do you love me? YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fn3KWM1kuAw

Bowen F (2014) After greenwashing: symbolic corporate environmentalism and society. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139541213

Coeckelbergh M (2021) Three responses to anthropomorphism in social robotics: towards a critical, relational, and hermeneutic approach. Int J Soc Robot. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12369-021-00770-0

Connelly BL, Certo ST, Ireland RD, Reutzel CR (2011) Signaling theory: a review and assessment. J Manag 37(1):39–67. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206310388419

Dacey M (2017) Anthropomorphism as cognitive bias. Philos Sci 84(5):1152–1164. https://doi.org/10.1086/694039

Davenport T, Guha A, Grewal D, Bressgott T (2020) How artificial intelligence will change the future of marketing. J Acad Mark Sci 48(1):24–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-019-00696-0

Draude C (2011) Intermediaries: reflections on virtual humans, gender, and the uncanny valley. AI & Soc 26(4):319–327. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-010-0312-4

Esterwood C, Essenmacher K, Yang H, Zeng F, Robert LP (2021) a meta-analysis of human personality and robot acceptance in human–robot interaction. In: Proceedings of the 2021 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, pp 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1145/3411764.3445542

Gahrn-Andersen R (2020) Seeming autonomy, technology and the uncanny valley. AI & Soc. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-020-01040-9

Giger J, Piçarra N, Alves-Oliveira P, Oliveira R, Arriaga P (2019) Humanization of robots: is it really such a good idea? Hum Behav Emerg Technol 1(2):111–123. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbe2.147

Gursoy D, Chi OH, Lu L, Nunkoo R (2019) Consumers acceptance of artificially intelligent (AI) device use in service delivery. Int J Inf Manag 49(March):157–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2019.03.008

Hauser S, Redström J, Wiltse H (2021) The widening rift between aesthetics and ethics in the design of computational things. AI & Soc. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-021-01279-w

Hofkirchner W, Kreowski H-J (eds) (2021) Transhumanism: the proper guide to a posthuman condition or a dangerous idea? Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-56546-6

Innerarity D (2021) Making the black box society transparent. AI & Soc 36(3):975–981. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-020-01130-8

Kim SY, Schmitt BH, Thalmann NM (2019a) Eliza in the uncanny valley: anthropomorphizing consumer robots increases their perceived warmth but decreases liking. Mark Lett. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11002-019-09485-9

Kim SY, Schmitt BH, Thalmann NM (2019b) Eliza in the uncanny valley: anthropomorphizing consumer robots increases their perceived warmth but decreases liking. Mark Lett 30(1):1–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11002-019-09485-9

Kim B, Bruce M, Brown L, De Visser E, Phillips E (2020) A comprehensive approach to validating the uncanny valley using the anthropomorphic RoBOT (ABOT) database. In: 2020 Systems and Information Engineering Design Symposium (SIEDS), pp 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1109/SIEDS49339.2020.9106675

Lauwaert L (2021) Artificial intelligence and responsibility. AI & Soc 36(3):1001–1009. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-020-01119-3

Li M, Suh A (2021) Machinelike or humanlike? A literature review of anthropomorphism in AI-enabled technology. In: Proceedings of the Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, 2020-Jan, pp 4053–4062. https://doi.org/10.24251/HICSS.2021.493

Lu L, Cai R, Gursoy D (2019) Developing and validating a service robot integration willingness scale. Int J Hosp Manag 80(7):36–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2019.01.005

Metz C (2018) These robots run, dance and flip. But are they a business? The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/09/22/technology/boston-dynamics-robots.html

Mori M, MacDorman K, Kageki N (2012) The uncanny valley [from the field]. IEEE Robot Autom Mag 19(2):98–100. https://doi.org/10.1109/MRA.2012.2192811

Murphy RR (2019) Introduction to AI robotics, second edition. The MIT Press

Nath R, Manna R (2021) From posthumanism to ethics of artificial intelligence. AI & Soc. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-021-01274-1

Nordström M (2021) AI under great uncertainty: implications and decision strategies for public policy. AI & Soc. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-021-01263-4

Obradovich N, Powers W, Cebrian M, Rahwan I, Content R (2019) Beware corporate “machinewashing” of AI. Media MIT. https://www.media.mit.edu/articles/beware-corporate-machinewashing-of-ai/

Paiva A, Leite I, Boukricha H, Wachsmuth I (2017) Empathy in virtual agents and robots. ACM Trans Interact Intell Syst 7(3):1–40. https://doi.org/10.1145/2912150

Parviainen J, Coeckelbergh M (2020) The political choreography of the Sophia robot: beyond robot rights and citizenship to political performances for the social robotics market. AI & Soc. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-020-01104-w

Pitt C, Paschen J, Kietzmann J, Pitt LF, Pala E (2021) Artificial intelligence, marketing, and the history of technology: Kranzberg’s laws as a conceptual lens. Australas Mark J. https://doi.org/10.1177/18393349211044175

Riva P, Sacchi S, Brambilla M (2015) Humanizing machines: anthropomorphization of slot machines increases gambling. J Exp Psychol Appl 21(4):313–325. https://doi.org/10.1037/xap0000057

Rzepka C, Berger B (2018) User interaction with AI-enabled systems: a systematic review of IS research. In: International Conference on Information Systems 2018, ICIS 2018. https://aisel.aisnet.org/icis2018/general/Presentations/7

Seele P (2021) Robot asks: do you love me ? No, it is just ‘humanwashing of Machines.’ Medium, 1–2. https://peter-seele.medium.com/robot-asks-do-you-love-me-no-it-is-just-humanwashing-of-machines-2753800a4eeb

Seele P, Schultz MD (2022) From greenwashing to machinewashing: a model and future directions derived from reasoning by analogy. J Bus Ethics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-022-05054-9

Shanahan M (2015) Opinion: machines may seem intelligent , but it’ll be a while before they actually are. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/in-theory/wp/2015/11/03/machines-may-seem-intelligent-but-itll-be-a-while-before-they-actually-are/

Sharkey N (2018) Mama Mia it’s Sophia: a show robot or dangerous platform to mislead? Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/noelsharkey/2018/11/17/mama-mia-its-sophia-a-show-robot-or-dangerous-platform-to-mislead/?sh=7648eb477ac9

Sorgner SL (2022) We have always been cyborgs: digital data, gene technologies, and an ethics of transhumanism. Bristol University Press

Tollon F, Naidoo K (2021) On and beyond artifacts in moral relations: accounting for power and violence in Coeckelbergh’s social relationism. AI & Soc. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-021-01303-z

Vincent J (2021) They’re putting guns on robot dogs now. The Verge. https://www.theverge.com/2021/10/14/22726111/robot-dogs-with-guns-sword-international-ghost-robotics

Vogt J (2021) Where is the human got to go? Artificial intelligence, machine learning, big data, digitalisation, and human–robot interaction in Industry 4.0 and 5.0. Ai & Soc 36(3):1083–1087. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-020-01123-7

Yam KC, Bigman YE, Tang PM, Ilies R, De Cremer D, Soh H, Gray K (2021) Robots at work: people prefer—and forgive—service robots with perceived feelings. J Appl Psychol 106(10):1557–1572. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000834

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università della Svizzera italiana. The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Scorici, G., Schultz, M.D. & Seele, P. Anthropomorphization and beyond: conceptualizing humanwashing of AI-enabled machines. AI & Soc 39, 789–795 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-022-01492-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-022-01492-1