Abstract

Purpose

There is growing interest in improving the inclusiveness of racial and ethnic minority participants in trials of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). With our study we aimed to examine temporal trends of representation and mortality of racial and ethnic minority participants in randomized controlled trials of ARDS.

Methods

We performed a secondary analysis of eight ARDS Network and PETAL Network therapeutic clinical trials, published between 2000 and 2019. We classified race/ethnicity into “White”, “Black”, “Hispanic”, or “Other” (including Asian, American Indian or Alaskan Native, Native Hawaiian, or other Pacific Islander participants).

Results

Of 5375 participants with ARDS, 1634 (30.4%) were Black, Hispanic, or Other race participants. Representation of racial and ethnic minority participants in trials did not change significantly over time (p = 0.257). However, among participants with moderate to severe ARDS (i.e., partial pressure of arterial oxygen to fraction of inspired oxygen ratio < 150), the difference in mortality between racial and ethnic minority participants and White participants decreased over time. In the five most recent trials, including 2923 participants with ARDS, there were no statistically significant differences in mortality between racial/ethnic groups, even after adjusting for potential confounders. In these five most recent trials, mortality was 31% for White, 31.9% for Black, 30.3% for Hispanic, and 37.1% for Other race participants (p = 0.633).

Conclusion

Representation of racial and ethnic minority participants in ARDS trials from North America, published between 2000 and 2019, did not change over time. Black and Hispanic participants with ARDS may have similar mortality as White participants within trials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Representation of racial and ethnic minority participants in trials of ARDS did not change significantly over time. Black and Hispanic participants with ARDS may have similar mortality as White participants within trials. |

Introduction

Consideration of racial and ethnic diversity groups has been identified as an opportunity for improved clinical trial design [1]. In 2021, the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities set the goal to increase the percentage of participants from diverse populations in clinical trials to 40 percent by the year 2030 in major disease categories [2], such as acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). Indeed, there is growing attention toward improving the inclusiveness of racial and ethnic minority participants in future ARDS trials [1, 3]. Despite this increasing interest [1, 4], the last relevant data on the representation and outcomes of racial and ethnic minority participants are based on trials of ARDS, which were published in 2000, 2004, and 2006 [5,6,7].

Based on previous evidence, racial and ethnic minority patients with ARDS are considered to be at higher risk of mortality than White patients [8]. This consideration may be supported by a secondary analysis (published in 2009 [9]) of data from the first three trials of the ARDS Network (namely, ARMA [5], ALVEOLI [6], and FACTT [7]). In that secondary analysis [9], Black and Hispanic patients with ARDS comprised 27.4% of the study population and were found to have a significantly higher risk of adverse outcomes (including mortality and ventilator-free days) than White patients [9]. Although racial and ethnic minority patients may have a higher risk of developing ARDS [10], updated data on their representation and outcomes in recent therapeutic trials of ARDS do not exist.

Accordingly, we endeavored to determine whether the representation of racial and ethnic minority participants in therapeutic trials of ARDS changed over time and to analyze the mortality of participants with ARDS by race/ethnicity within trials. Part of this work has previously been presented at an international meeting of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine and published as an abstract [11].

Methods

Study design and patient population

We performed a secondary analysis of data from eight ARDS Network and Prevention and Early Treatment of Acute Lung Injury (PETAL) Network prospective therapeutic clinical trials (namely, ARMA [5], ALVEOLI [6], FACTT [7], ALTA [12], EDEN [13], SAILS [14], ROSE [15], and VIOLET [16]). Details on the geographical locations of those trials are provided in the online data supplement (eMethods). Participants from the OMEGA trial [17] were included in this analysis as part of the EDEN trial [13]. Participants from the LaSRS trial [18] were not considered, as they needed to have late-phase ARDS. In those trials [5,6,7, 12,13,14,15], no racial/ethnic group was excluded, and participants had to receive positive-pressure mechanical ventilation through an endotracheal tube, had a partial pressure of arterial oxygen to fraction of inspired oxygen ratio (PaO2/FiO2) ≤ 300, and had bilateral infiltrates on chest radiography not fully explained by cardiac failure. Similarly, participants from the VIOLET trial with ARDS at baseline were included in this analysis [16]. As previously described [19, 20], we were granted access to data through the Biologic Specimen and Data Repository Information Coordinating Center (BioLINCC) of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI). Because data would be received in de-identified form, the Institutional Review Board of Evangelismos Hospital, Athens, Greece waived the need of informed consent and approved the study (141/05-05-2022).

Study groups

As previously described [9], we classified race/ethnicity into four mutually exclusive categories: “White” (including only White, non-Hispanic participants), “Black” (including only Black, non-Hispanic participants), “Hispanic”, or “Other” (including non-White, non-Black, non-Hispanic, participants). The “Other” race category was provided in an aggregated form from the original trials (except from VIOLET [16]) and included Asian, American Indian or Alaskan Native, Native Hawaiian, or other Pacific Islander participants. Participants without documented race/ethnicity were only included in sensitivity analyses; the study-level distribution of these participants is available as supplemental Table E1 in the online data supplement. Additional details on the classification of participants into race/ethnicity study groups are availables supplementary eMethods.

Study outcomes

The primary outcomes of the present analysis were the proportion of racial and ethnic minority participants within ARDS therapeutic trials and 90-day mortality, with participants discharged from the hospital prior to 90 days considered to be alive at 90 days. We chose to examine mortality at day 90 because participants in ARDS Network and PETAL Network trials [5,6,7, 12,13,14,15,16] were followed through day 90 unless they were discharged home earlier. Secondary outcomes were differences in organ failure-free days, ventilator-free days, and intensive care unit (ICU)-free days between racial/ethnic groups through day 28 following enrollment, as previously described [21, 22]. Also, we estimated differences in the occurrence of rapidly improving ARDS (defined as extubation or a PaO2/FiO2 > 300 on the first study day following enrollment) [23, 24] and prolonged mechanical ventilation (defined as the need of mechanical ventilation after day 21 following enrollment) [25] between racial/ethnic groups. To better reflect contemporary clinical practice, and given that a similar secondary analysis of the first three trials [5,6,7] was already published [9], we considered only data from the five most recent trials [12,13,14,15,16] for the analyses of baseline characteristics and outcomes.

Sensitivity analyses

We performed sensitivity analyses by considering participants without documented race/ethnicity either as a separate category or as part of the Other race category.

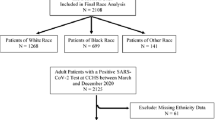

Also, to further update our findings by considering trials beyond the ARDS Network and PETAL Network, we performed a sensitivity analysis using data from therapeutic trials, which were published in 2021 and enrolled participants hospitalized with the new coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), namely the Adaptive COVID-19 Treatment Trial (ACTT)-2 [26] and ACTT-3 [27]. For this sensitivity analysis, we only included ACTT-2 and ACTT-3 participants with ARDS, defined as the need for invasive mechanical ventilation and/or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. We were granted access to those data through the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID).

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were presented as median with interquartile range (IQR) and compared using the Kruskal–Wallis test. Categorical variables were presented as percentages and compared using the chi-squared or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. To estimate the pooled prevalence and pooled 90-day mortality of racial and ethnic minority participants across trials, proportional meta-analyses using inverse variance weights and random-effects models (DerSimonian & Laird) were performed. To stabilize variances, the Freeman–Tukey double arcsine transformation and then back-transformation for ease of interpretation were used [28, 29]. The prevalence of racial and ethnic minority participants was estimated over time via a meta-regression analysis, with time as the independent variable and within-study prevalence of minorities as the dependent variable. Mortality was estimated over time via a meta-regression analysis, with time as the independent variable and the natural logarithm of odds ratio for mortality of minorities compared to the mortality of White participants as the dependent variable. Meta-regression analyses were performed using inverse variance weights and random-effects models.

The association between race/ethnicity and 90-day mortality (primary outcome) was tested with a Cox proportional hazards regression analysis taking into consideration trial, age, sex, comorbidities (presence versus absence), PaO2/FiO2, and non-pulmonary organ failures on the day of enrollment, as previously described in the literature [9]. Potential violations of the proportional hazards assumption were assessed using scaled Schoenfeld residuals for each covariate [30] and were addressed by bootstrap techniques using 2000 resamples with 95% confidence intervals (CI) being estimated using the bias-corrected accelerated method [31]. Also, the linearity of the continuous covariates (namely, age and PaO2/FiO2 at the day of enrollment) was assessed and confirmed using Martingale residuals [30]. To further evaluate the association between race/ethnicity and 90-day mortality, a sensitivity Cox proportional hazards regression analysis with participants discharged from the hospital prior to 90 days considered to be dead at 90 days was performed. To construct the Cox proportional hazards regression model, all available information on mortality and the included variables were used. Missing data on outcomes were below 4% (supplementary Table E2 in the online data supplement). All p values were two-sided, and statistical significance was considered at an α level of 0.05. All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS software version 28.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and R software version 4.2.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

Results

Temporal trends of representation and mortality of racial and ethnic minority participants

Out of 5375 participants with ARDS enrolled in eight ARDS Network and PETAL Network randomized controlled trials [5,6,7, 12,13,14,15,16], 1634 (30.4%) were racial and ethnic minority participants (namely, Black, Hispanic or Other race). Baseline characteristics by race/ethnicity are presented in supplementary Table E3. In all eight trials [5,6,7, 12,13,14,15,16], the pooled prevalence of racial and ethnic minority participants was 30.4% (95% CI 27.7–33.2%) ranging from 24.9% in the ALVEOLI trial [6] to 38.5% in VIOLET trial [16] (supplementary Fig. E1). Representation of racial and ethnic minority participants in therapeutic clinical trials of ARDS did not change significantly over time (p = 0.257) (Fig. 1).

In all eight trials [5,6,7, 12,13,14,15,16], the pooled 90-day mortality of racial and ethnic minority participants was 33% (95% CI 27.8–38.5%) (supplementary Fig. E2). To assess temporal trends of mortality, we focused our analysis on participants with moderate to severe ARDS (defined as PaO2/FiO2 < 150) [32] because the ROSE trial only included such participants [15]. A total of 3244 participants had moderate to severe ARDS and were included in this analysis. In the first three ARDS Network trials (namely, ARMA [5], ALVEOLI [6], and FACTT [7]), the mortality rate of racial and ethnic minority participants was higher than the mortality rate of White participants. However, in the five most recent trials (namely, ALTA [12], EDEN [13], SAILS [14], ROSE [15], and VIOLET [16]), the difference in mortality between racial and ethnic minority participants and White participants with moderate to severe ARDS decreased (Fig. 2A). Meta-regression analysis found a significant effect of time on the difference in mortality between racial and ethnic minority participants and White participants with moderate to severe ARDS (p = 0.021) (Fig. 2B). As detailed in supplementary Table E4, the mortality rate changed from 35.7% for White and 44.2% for racial and ethnic minority participants in the ARMA trial [5] (p = 0.072) to 47.2% for White and 46.7% for racial and ethnic minority participants in VIOLET trial [16] (p = 0.964). Additional details on temporal trends of mortality rates per racial/ethnic group (namely, White, Black, Hispanic, or Other race) are available in supplementary Table E5. Temporal trends of mortality in the total population, regardless of ARDS severity, are presented in supplementary Fig. E3 and Table E6.

A Mortality of racial and ethnic minority participants (green circles) and White participants (red circles) with moderate to severe ARDS in eight ARDS Network and PETAL Network clinical trials is plotted. B The difference in mortality between racial and ethnic minority participants and White participants with moderate to severe ARDS decreased over time (p = 0.021)

To better reflect contemporary clinical practice, the remainder of our analyses considered only data from the five most recently published clinical trials; namely, ALTA [12], EDEN [13], SAILS [14], ROSE [15], and VIOLET [16] (all published after 2010). The latter trials [12,13,14,15,16] enrolled a total of 2923 participants with ARDS; i.e., 2026 (69.3%) White, 448 (15.3%) Black, 360 (12.3%) Hispanic, and 89 (3%) Other race participants.

Baseline characteristics οf participants by race/ethnicity

Table 1 depicts baseline characteristics of participants by race/ethnicity. The median (IQR) age of White, Black, Hispanic, and Other race participants was 56 (44–67), 52.5 (41–62), 51 (40–60), and 57 (41–69.5) years, respectively. There were no substantial differences between racial/ethnic groups in terms of sex, primary risk factor of ARDS, and usage of steroids. There were differences between groups in terms of comorbidities (Table 1). Renal failure was more common in Black (34.2%) and Hispanic (29.4%) participants compared to White (26%) and Other race (24.7%) participants.

Regarding baseline lung mechanics, there were no substantial differences between groups in terms of tidal volume per predicted body weight and positive end-expiratory pressure. However, median PaO2/FiO2 was lower in Hispanic participants [117.5 (84–162)], while median driving pressure was higher in Black [15 (12–18.8) cmH2O] and Other race [(15 (10.8–18.3) cmH2O] participants than comparators.

Outcomes of participants by race/ethnicity

Table 2 depicts the outcomes of participants by race/ethnicity. There were no statistically significant differences between racial/ethnic groups in terms of 90-day mortality; the mortality rate was 31% (628 of 2026) for White, 31.9% (143 of 448) for Black, 30.3% (109 of 360) for Hispanic, and 37.1% (33 of 89) for Other race participants (p = 0.633). Supplementary Table E7 depicts outcomes by race/ethnicity with Black, Hispanic, and Other race participants combined as one group. Consistently, in a Cox regression analysis shown in Table 3, race/ethnicity was not independently associated with 90-day mortality after controlling for trial, age, sex, comorbidities, PaO2/FiO2 and non-pulmonary organ failures at day of enrollment [with White participants being the reference category; Hazard ratio (HR) = 1.133; 95% CI 0.941–1.364 for Black participants; HR = 0.973; 95% CI 0.788–1.202 for Hispanic participants; and HR = 1.148; 95% CI 0.804–1.640 for Other race participants]. Even after utilizing bootstrap techniques, race/ethnicity was not independently associated with 90-day mortality (supplementary Table E8). This was also the case for the sensitivity Cox regression analyses by adding the effect of intervention/control per each trial in the model (supplementary Table E9), and by considering participants discharged from the hospital prior to 90 days as dead at 90 days. With regard to secondary outcomes, Other race participants had fewer ICU-free days than comparators (Table 2).

Sensitivity analyses

In the sensitivity analyses by considering participants without documented race/ethnicity either as a separate category or as part of the Other race category, race/ethnicity was again not independently associated with mortality. Relevant results are presented in supplementary Tables E10 and E11, respectively.

Consistently, this was also the case for the sensitivity analysis of data from the ACTT-2 [26] and ACTT-3 [27] randomized controlled trials (supplementary Table E12). In this sensitivity analysis, Black and Hispanic participants with ARDS did not have higher mortality than White participants. Details are provided as eResults in the online data supplement.

Discussion

This secondary analysis of data from 5375 participants with ARDS included in eight ARDS Network and PETAL Network therapeutic trials suggests that the representation of racial and ethnic minority participants did not change significantly over time. However, the difference in mortality between racial and ethnic minority participants and White participants in trials of ARDS decreased. In the five most recently published trials, there were no statistically significant differences in mortality between White, Black, Hispanic, and Other race participants, even after adjusting for confounders.

The results of the present secondary analysis may be useful to ARDS clinical trialists. Clinical trialists have identified as a primary strategy to improve the design of ARDS trials the increase in the representativeness of clinical trial populations [1]. We found that the representation of racial and ethnic minority participants in therapeutic trials of ARDS did not change from 2000 to 2019. Therefore, given that the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities aimed to increase the percentage of participants from diverse populations in clinical research to 40 percent by 2030, there is still potential for improvement. That being said, the representation of Black participants within ARDS Network and PETAL Network trials was found to be 16.7%, while their estimated representation in the US population is 12.6% [4], probably due to their higher risk of developing ARDS [10]. Taken together, our findings (in accordance with previous evidence [33]) suggest that the problem of not sufficiently reporting [4] or including racially and ethnically marginalized communities may not be as large in ARDS as in other fields, such as heart failure [34] or cancer [35].

The present secondary analysis found that the difference in mortality between racial and ethnic minority participants and White participants with ARDS decreased. Also, the prevalence of rapidly improving ARDS, that has been associated with better outcomes compared to ARDS > 1 day [23], did not differ between racial/ethnic groups. Exploring the cause of these intriguing findings was beyond the scope of this analysis. However, one could make the conjecture that changes in mortality over 20 years may be reflective of altered comorbidity burdens, staffing burdens of institutions, and/or growing expertise in the management of patients with ARDS, regardless of race/ethnicity [5, 23, 32, 36]. Our findings might be an indication of ever-increasing awareness among clinicians to provide optimal management of racial and ethnic minority patients with ARDS.

Our finding that there was no statistically significant difference in outcomes between racial/ethnic groups seems to be at odds with evidence outside ARDS Network and PETAL Network trials. It is thought that Black and Hispanic patients with ARDS are at higher risk of mortality than White patients [8, 37], and this has been partially attributed to the fact that pulse oximetry might overestimate oxygenation of patients of color [8]. Although pulse oximetry-derived overestimation of oxygenation in patients of color indeed affects the administration of supplemental oxygen [38, 39], this might have been inconsequential in the ARDS Network and PETAL Network trials where the management of patients was primarily based on PaO2 rather than the saturation of peripheral oxygen (SpO2). Beyond pulse oximetry, it is possible that the overall protocolized nature of randomized controlled trials might improve care for racial and ethnic minority patients as compared to “real life” situations where unconscious and conscious biases may be less mitigated by highly protocolized and idealized care that occurs within trials.

Our study has limitations. First, the “Other” race category was provided in an aggregated form from the original ARDS Network and PETAL Network trials (except from VIOLET [16]) and included Asian, American Indian or Alaskan Native, Native Hawaiian, or other Pacific Islander participants. Thus, due to the subsequent heterogeneity of this race category, the observed differences in organ failure-free days, ventilator-free days, and ICU-free days between the “Other” race participants and comparators were difficult to interpret and need further evaluation. Accordingly, we suggest that all trials collect and report disaggregated granular data on race/ethnicity to allow for future research on outcomes of Asian, American Indian or Alaskan Native, Native Hawaiian, or other Pacific Islander participants. Second, it is a post hoc secondary analysis. However, we designed the statistical plan prospectively in our study protocol, which was given to BioLINCC. Third, recruitment for these clinical trials often occurs at large academic centers and thus our findings may not represent nonacademic hospitals that provide the majority of care to racial and ethnic minority patients.

Fourth, the ARDS Network and PETAL Network trials exclusively enrolled participants from North America and thus their conclusions may not be generalizable to other continents. However, we performed a sensitivity analysis of data from the ACTT-2 [26] and ACTT-3 [27] trials, which did not limit their enrollment to sites in North America; rather they also enrolled participants from Asia and Europe. In this sensitivity analysis of ACTT trials, we again found that Black and Hispanic participants with ARDS did not have higher mortality than White participants. Fifth, there were no available data on the consent rates in racial/ethnic groups. A relevant secondary analysis of the first three ARDS Network trials [5,6,7] found that racial and ethnic minority patients were more likely than White patients to be excluded due to lack of consent [33]. Sixth, there are other diversity groups, such as those based on sex [40, 41] that may influence outcomes of patients with ARDS. Nevertheless, the assessment of the effect of such diversity groups on the outcomes of ARDS was out of the scope of the current study. Seventh, due to the limited number of events in the “Other” race category, we included comorbidities in a simplified (presence versus absence) manner rather than a detailed (each comorbidity) manner in the Cox regression analysis. Finally, we did not have information on the social demographics of health variables, including the socioeconomic status of participants, which are important confounders when assessing race and ethnicity-based disparities [42].

Conclusions

In conclusion, we found that the representation of racial and ethnic minority participants in ARDS trials from North America, published between 2000 and 2019, did not change significantly over time. Black and Hispanic participants with ARDS may have similar mortality as White participants within trials.

Data availability

Data which this secondary analysis was based on are available through the Biologic Specimen and Data Repository Information Coordinating Center of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (https://biolincc.nhlbi.nih.gov/home/).

References

Wick KD, Aggarwal NR, Curley MAQ, Fowler AA 3rd, Jaber S, Kostrubiec M, Lassau N, Laterre PF, Lebreton G, Levitt JE, Mebazaa A, Rubin E, Sinha P, Ware LB, Matthay MA (2022) Opportunities for improved clinical trial designs in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Lancet Respir Med 10(9):916–924. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(22)00294-6

The National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities Leap Forward Research Challenge (2021) https://www.nimhd.nih.gov/about/strategic-plan/nih-strategic-plan-leap-forward-research-challenge.html

Thakur N, Lovinsky-Desir S, Appell D, Bime C, Castro L, Celedón JC, Ferreira J, George M, Mageto Y, Mainous AG III, Pakhale S, Riekert KA, Roman J, Ruvalcaba E, Sharma S, Shete P, Wisnivesky JP, Holguin F (2021) Enhancing recruitment and retention of minority populations for clinical research in pulmonary, critical care, and sleep medicine: an official American thoracic society research statement. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 204:e26–e50. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.202105-1210ST

Turner BE, Steinberg JR, Weeks BT, Rodriguez F, Cullen MR (2022) Race/ethnicity reporting and representation in US clinical trials: a cohort study. Lancet Reg Health Am 11:100252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lana.2022.100252

Network ARDS, Brower RG, Matthay MA, Morris A, Schoenfeld D, Thompson BT, Wheeler A (2000) Ventilation with lower tidal volumes as compared with traditional tidal volumes for acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med 342:1301–1308. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM200005043421801

Brower RG, Lanken PN, MacIntyre N, Matthay MA, Morris A, Ancukiewicz M, Schoenfeld D, Thompson BT, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute ARDS Clinical Trials Network (2004) Higher versus lower positive end-expiratory pressures in patients with the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med 351:327–336. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa032193

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) Clinical Trials Network, Wiedemann HP, Wheeler AP, Bernard GR, Thompson BT, Hayden D, deBoisblanc B, Connors AF Jr, Hite RD, Harabin AL (2006) Comparison of two fluid-management strategies in acute lung injury. N Engl J Med 354:2564–2575. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa062200

Wick KD, Matthay MA, Ware LB (2022) Pulse oximetry for the diagnosis and management of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Lancet Respir Med 10:1086–1098. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(22)00058-3

Erickson SE, Shlipak MG, Martin GS, Wheeler AP, Ancukiewicz M, Matthay MA, Eisner MD, National Institutes of Health National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Network (2009) Racial and ethnic disparities in mortality from acute lung injury. Crit Care Med 37:1–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0b013e31819292ea

Barnato AE, Alexander SL, Linde-Zwirble WT, Angus DC (2008) Racial variation in the incidence, care, and outcomes of severe sepsis: analysis of population, patient, and hospital characteristics. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 177(3):279–284. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200703-480OC

Papoutsi E, Zacharis A, Athanasiou GVG, Routsi C, Kotanidou A, Siempos I (2022) Temporal trends of representation and outcomes of racial minorities in therapeutic clinical trials of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Intensive Care Med Exp 10(2):000361. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40635-022-00468-1

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) Clinical Trials Network, Matthay MA, Brower RG, Carson S, Douglas IS, Eisner M, Hite D, Holets S, Kallet RH, Liu KD, MacIntyre N, Moss M, Schoenfeld D, Steingrub J, Thompson BT (2011) Randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial of an aerosolized β2-agonist for treatment of acute lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 184:561–568

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) Clinical Trials Network, Rice TW, Wheeler AP, Thompson BT, Steingrub J, Hite RD, Moss M, Morris A, Dong N, Rock P (2012) Initial trophic vs full enteral feeding in patients with acute lung injury: the EDEN randomized trial. JAMA 307:795–803. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2012.137

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute ARDS Clinical Trials Network, Truwit JD, Bernard GR, Steingrub J, Matthay MA, Liu KD, Albertson TE, Brower RG, Shanholtz C, Rock P, Douglas IS, deBoisblanc BP, Hough CL, Hite RD, Thompson BT (2014) Rosuvastatin for sepsis-associated acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med 370:2191–2200. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1401520

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute PETAL Clinical Trials Network, Moss M, Huang DT, Brower RG, Ferguson ND, Ginde AA, Gong MN, Grissom CK, Gundel S, Hayden D, Hite RD, Hou PC, Hough CL, Iwashyna TJ, Khan A, Liu KD, Talmor D, Thompson BT, Ulysse CA, Yealy DM, Angus DC (2019) Early neuromuscular blockade in the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med 380:1997–2008. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1901686

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute PETAL Clinical Trials Network, Ginde AA, Brower RG, Caterino JM, Finck L, Banner-Goodspeed VM, Grissom CK, Hayden D, Hough CL, Hyzy RC, Khan A, Levitt JE, Park PK, Ringwood N, Rivers EP, Self WH, Shapiro NI, Thompson BT, Yealy DM, Talmor D (2019) Early high-dose Vitamin D(3) for critically Ill, vitamin D-deficient patients. N Engl J Med 381:2529–2540. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1911124

Rice TW, Wheeler AP, Thompson BT, deBoisblanc BP, Steingrub J, Rock P, NIH NHLBI Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Network of Investigators (2011) Enteral omega-3 fatty acid, gamma-linolenic acid, and antioxidant supplementation in acute lung injury. JAMA 306(14):1574–1581. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2011.1435

Steinberg KP, Hudson LD, Goodman RB, Hough CL, Lanken PN, Hyzy R, Thompson BT, Ancukiewicz M, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) Clinical Trials Network (2006) Efficacy and safety of corticosteroids for persistent acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med 354(16):1671–1684. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa051693

Papoutsi E, Routsi C, Kotanidou A, Vaporidi K, Siempos II (2023) Association between driving pressure and mortality may depend on timing since onset of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Intensive Care Med 49:363–365. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-023-06996-y

Papoutsi E, Giannakoulis VG, Routsi C, Kotanidou A, Siempos II (2023) Association between ventilatory ratio and mortality persists in patients with ARDS requiring prolonged mechanical ventilation. Intensive Care Med 49:876–877. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-023-07107-7

Price DR, Hoffman KL, Sanchez E, Choi AMK, Siempos II (2021) Temporal trends of outcomes of neutropenic patients with ARDS enrolled in therapeutic clinical trials. Intensive Care Med 47:122–123. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-020-06263-4

Price DR, Hoffman KL, Oromendia C, Torres LK, Schenck EJ, Choi ME, Choi AMK, Baron RM, Huh JW, Siempos II (2021) Effect of neutropenic critical illness on development and prognosis of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 203:504–508. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.202003-0753LE

Schenck EJ, Oromendia C, Torres LK, Berlin DA, Choi AMK, Siempos II (2019) Rapidly improving ARDS in therapeutic randomized controlled trials. Chest 155:474–482. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2018.09.031

Gavrielatou E, Vaporidi K, Tsolaki V, Tserlikakis N, Zakynthinos GE, Papoutsi E, Maragkuti A, Mantelou AG, Karayiannis D, Mastora Z, Georgopoulos D, Zakynthinos E, Routsi C, Zakynthinos SG, Schenck EJ, Kotanidou A, Siempos II (2022) Rapidly improving acute respiratory distress syndrome in COVID-19: a multi-centre observational study. Respir Res 23:94. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-022-02015-8

MacIntyre NR, Epstein SK, Carson S, Scheinhorn D, Christopher K, Muldoon S (2005) Management of patients requiring prolonged mechanical ventilation: report of a NAMDRC consensus conference. Chest 128:3937–3954. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.128.6.3937

Kalil AC, Patterson TF, Mehta AK, Tomashek KM, Wolfe CR, Ghazaryan V, Marconi VC, Ruiz-Palacios GM, Hsieh L, Kline S, Tapson V, Iovine NM, Jain MK, Sweeney DA, El Sahly HM, Branche AR, Regalado Pineda J, Lye DC, Sandkovsky U, Luetkemeyer AF, Cohen SH, Finberg RW, Jackson PEH, Taiwo B, Paules CI, Arguinchona H, Erdmann N, Ahuja N, Frank M, Oh MD, Kim ES, Tan SY, Mularski RA, Nielsen H, Ponce PO, Taylor BS, Larson L, Rouphael NG, Saklawi Y, Cantos VD, Ko ER, Engemann JJ, Amin AN, Watanabe M, Billings J, Elie MC, Davey RT, Burgess TH, Ferreira J, Green M, Makowski M, Cardoso A, de Bono S, Bonnett T, Proschan M, Deye GA, Dempsey W, Nayak SU, Dodd LE, Beigel JH, ACTT-2 Study Group Members (2021) Baricitinib plus remdesivir for hospitalized adults with COVID-19. N Engl J Med 384(9):795–807. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2031994

Kalil AC, Mehta AK, Patterson TF, Erdmann N, Gomez CA, Jain MK, Wolfe CR, Ruiz-Palacios GM, Kline S, Regalado Pineda J, Luetkemeyer AF, Harkins MS, Jackson PEH, Iovine NM, Tapson VF, Oh MD, Whitaker JA, Mularski RA, Paules CI, Ince D, Takasaki J, Sweeney DA, Sandkovsky U, Wyles DL, Hohmann E, Grimes KA, Grossberg R, Laguio-Vila M, Lambert AA, Lopez de Castilla D, Kim E, Larson L, Wan CR, Traenkner JJ, Ponce PO, Patterson JE, Goepfert PA, Sofarelli TA, Mocherla S, Ko ER, Ponce de Leon A, Doernberg SB, Atmar RL, Maves RC, Dangond F, Ferreira J, Green M, Makowski M, Bonnett T, Beresnev T, Ghazaryan V, Dempsey W, Nayak SU, Dodd L, Tomashek KM, Beigel JH, ACTT-3 study group members (2021) Efficacy of interferon beta-1a plus remdesivir compared with remdesivir alone in hospitalised adults with COVID-19: a double-bind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Respir Med 9(12):1365–1376. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00384-2

Barker TH, Migliavaca CB, Stein C, Colpani V, Falavigna M, Aromataris E, Munn Z (2021) Conducting proportional meta-analysis in different types of systematic reviews: a guide for synthesisers of evidence. BMC Med Res Methodol 21(1):189. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-021-01381-z

Schwarzer G, Rücker G (2022) Meta-analysis of proportions. Methods Mol Biol 2345:159–172. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-0716-1566-9_10

Lefebvre F, Giorgi R (2021) A strategy for optimal fitting of multiplicative and additive hazards regression models. BMC Med Res Methodol 21(1):100. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-021-01273-2

Stensrud MJ, Hernán MA (2020) Why test for proportional hazards? JAMA 323(14):1401–1402. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.1267

Ranieri VM, Rubenfeld GD, Thompson BT, Ferguson ND, Caldwell E, Fan E, Camporota L, Slutsky AS (2012) Acute respiratory distress syndrome: the Berlin definition. JAMA 307:2526–2533. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2012.5669

Cooke CR, Erickson SE, Watkins TR, Matthay MA, Hudson LD, Rubenfeld GD (2010) Age-, sex-, and race-based differences among patients enrolled versus not enrolled in acute lung injury clinical trials. Crit Care Med 38:1450–1457. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181de451b

DeFilippis EM, Echols M, Adamson PB, Batchelor WB, Cooper LB, Cooper LS, Desvigne-Nickens P, George RT, Ibrahim NE, Jessup M, Kitzman DW, Leifer ES, Mendoza M, Piña IL, Psotka M, Senatore FF, Stein KM, Teerlink JR, Yancy CW, Lindenfeld J, Fiuzat M, O’Connor CM, Vardeny O, Vaduganathan M (2022) Improving enrollment of underrepresented racial and ethnic populations in heart failure trials: a call to action from the heart failure collaboratory. JAMA Cardiol 7:540–548. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamacardio.2022.0161

Loree JM, Anand S, Dasari A, Unger JM, Gothwal A, Ellis LM, Varadhachary G, Kopetz S, Overman MJ, Raghav K (2019) Disparity of race reporting and representation in clinical trials leading to cancer drug approvals from 2008 to 2018. JAMA Oncol 5:e191870. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.1870

Jolley SE, Hough CL, Clermont G, Hayden D, Hou S, Schoenfeld D, Smith NL, Thompson BT, Bernard GR, Angus DC (2017) Relationship between race and the effect of fluids on long-term mortality after acute respiratory distress syndrome. Secondary analysis of the national heart, lung, and blood institute fluid and catheter treatment trial. Ann Am Thorac Soc 14:1443–1449. https://doi.org/10.1513/AnnalsATS.201611-906OC

McGowan SK, Sarigiannis KA, Fox SC, Gottlieb MA, Chen E (2022) Racial disparities in ICU Outcomes: a systematic review. Crit Care Med 50:1–20. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000005269

Sjoding MW, Dickson RP, Iwashyna TJ, Gay SE, Valley TS (2020) Racial bias in pulse oximetry measurement. N Engl J Med 383:2477–2478. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMc2029240

Gottlieb ER, Ziegler J, Morley K, Rush B, Celi LA (2022) Assessment of racial and ethnic differences in oxygen supplementation among patients in the intensive care unit. JAMA Intern Med 182:849–858. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2022.2587

McNicholas BA, Madotto F, Pham T, Rezoagli E, Masterson CH, Horie S, Bellani G, Brochard L, Laffey JG, LUNG SAFE Investigators and the ESICM Trials Group (2019) Demographics, management and outcome of females and males with acute respiratory distress syndrome in the LUNG SAFE prospective cohort study. Eur Respir J 54(4):1900609. https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.00609-2019

Steinberg JR, Turner BE, Weeks BT, Magnani CJ, Wong BO, Rodriguez F, Yee LM, Cullen MR (2021) Analysis of female enrollment and participant sex by burden of disease in US clinical trials between 2000 and 2020. JAMA Netw Open 4(6):e2113749. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.13749

Sangaramoorthy M, Shariff-Marco S, Conroy SM, Yang J, Inamdar PP, Wu AH, Haiman CA, Wilkens LR, Gomez SL, Le Marchand L, Cheng I (2022) Joint associations of race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status with mortality in the multiethnic cohort study. JAMA Netw Open 5:e226370. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.6370

Acknowledgements

This secondary analysis was prepared using ARMA, ALVEOLI, FACTT, ALTA, EDEN, SAILS, ROSE PETAL, and VIOLET PETAL research materials obtained from the Biologic Specimen and Data Repository Information Coordinating Center (BioLINCC) of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI). In addition, this secondary analysis was prepared in part using Adaptive COVID-19 Treatment Trial (ACTT)-2 and ACTT-3 research materials obtained from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID). The article does not necessarily reflect the opinions or views of the researchers who performed these trials or the NHLBI or the NIAID. The authors acknowledge the incredible work by the ARDS Network, PETAL Network, and ACTT researchers, without which this study would not have been possible.

Funding

Open access funding provided by HEAL-Link Greece. This study was supported by a grant to IIS from the Hellenic Foundation for Research and Innovation (H.F.R.I.) under the “2nd Call for H.F.R.I Research Projects to support Post-Doctoral Researchers” (Project 80- 1/15.10.2020).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

EP and IIS had full access to all of the data in the study and took responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. EP and IIS contributed to the concept and design of the study. EP, PK, VT, AK, CR, AK, and IIS were responsible for data acquisition and/or interpretation of the data. EP undertook statistical analyses and drafted the manuscript. PK, VT, AK, CR, AK, and IIS critically revised the manuscript for intellectual content and gave final approval of the manuscript. IIS supervised the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest in relation to this manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Papoutsi, E., Kremmydas, P., Tsolaki, V. et al. Racial and ethnic minority participants in clinical trials of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Intensive Care Med 49, 1479–1488 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-023-07238-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-023-07238-x