Abstract

Purpose

To establish longitudinal rates of post-traumatic stress in a cohort of child–parent pairs; to determine associations with poorer outcome.

Method

This was a prospective longitudinal cohort study set in a 21-bed unit. In total 66 consecutive admissions aged 7–17 years were screened with one parent at 3 and 12 months post-discharge. Measures used were the Children’s Revised Impact of Event Scale (CRIES-8) and the SPAN (short form of Davidson Trauma Scale).

Results

In total 29 (44 %) child–parent pairs contained at least one member who scored above cut-off 12 months after discharge, with scores increasing over time for 18 parents and 26 children. At 3 months, 28 (42 %) parents and 20 (32 %) children scored above cut-off; at 12 months the rates were 18 (27 %) parents and 17 (26 %) children. Parents scoring above cut-off at 12 months were more likely to have had a child admitted non-electively (100 % vs. 77 %, p = 0.028); had higher 3-month anxiety scores (11.5 vs. 4.5, p = 0.001) and their children had higher post-traumatic stress scores at 3 months (14 vs. 8, p = 0.017). Children who scored above cut-off at 12 months had higher 3-month post-traumatic stress scores (18 vs. 7, p = 0.001) and higher Paediatric Index of Mortality (PIM) scores on admission (10 vs. 4, p = 0.037).

Conclusions

The findings that (a) nearly half of families were still experiencing significant symptoms of post-traumatic stress 12 months after discharge; (b) their distress was predicted more by subjective than by objective factors and (c) many experienced delayed reactions, indicate the need for longer-term monitoring and more support for families in this situation

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

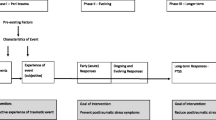

Recent guidelines on the management of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) [1] have endorsed a move away from the provision of blanket interventions, recommending instead that at risk populations are monitored for a period before evidence-based interventions are offered to those with significant or persistent symptoms. Such an approach depends on the use of validated screening instruments [2] but, in practice, routine screening for post-traumatic stress after traumatic events is rare, outside the research context. This situation is partly related to the small number of psychologists and psychiatrists working in medical settings, but is also the result of the lack of awareness of suitable validated screening instruments on the part of health professionals who are most likely to be in contact with families in the aftermath of traumatic medical events.

Children admitted to a Pediatric Intensive Care Unit (PICU) are theoretically at increased risk of the development of PTSD since they are, by definition, at increased risk of death. There is cross-sectional evidence that they report higher rates of post-traumatic stress symptoms than children admitted to general wards and that their symptoms are positively correlated with those of their parents [3] and more common in children who recall delusional experiences during admission [4]. However, little information is available on how children’s symptoms, or those of their parents, who are at even higher risk [5, 6], develop or resolve in the longer term. The authors of a recent review of psychological outcome studies [7] conclude that PICU patients exhibit significant psychiatric morbidity and that there is a need for more research in this area on how their symptoms change over time and interact with parental psychopathology.

Furthermore, recent guidelines on rehabilitation of adult intensive care survivors [8] have identified these patients and their relatives as needing regular psychological monitoring in recognition of the evidence of psychopathology in these groups [9, 10]. It could be argued that the need to monitor family members is even more pertinent in paediatric settings where patients are particularly dependent on their parents for their medical care and emotional well-being.

The main aim of this exploratory study was to use brief screening instruments to monitor the levels of post-traumatic stress symptoms in child–parent pairs at 3 and 12 months post-discharge. In doing so we hoped that it would be possible to establish more information about the natural history of these symptoms in this population. In recognition of the limited information available currently on which aspects of the intensive care experience are found to be most traumatic [11], participants were asked to state the ‘worst thing’ that they had experienced. Finally, associations with post-traumatic stress status 12 months after discharge were examined.

On the basis of previous research it was hypothesised that a significant minority of participants would score in the clinical range and that, in the majority of adults, symptoms would reduce over time [12]. It was less clear how the children would fare owing to the limited longitudinal evidence available, although there is some research suggesting that children may be more prone to delayed reactions [13] and a recent epidemiological study has shown that post-traumatic stress symptoms take longer to remit naturally after childhood trauma [14].

Method

Participants

Participants were children aged 7–17 years and their primary carers. All children had been consecutively admitted over an 18-month period to a tertiary centre 21-bed PICU and had previously been interviewed about their experiences of PICU, 3 months after discharge. Principal exclusion criteria were significant learning difficulties and readmission during the study period. The lower end of the age range of the children in the sample was determined by the requirements of the original study [4], which focused on the nature of children’s memories of PICU and how these were associated with sedation and distress.

Procedure

Ethical permission for the original study and this follow-up study was granted by the Great Ormond Street/Institute of Child Health Research Ethics Committee and written informed consent obtained. Demographic and medical data were obtained from the child’s medical record. Illness severity in the first 24 h of admission was measured using the Paediatric Index of Mortality (PIM) [15]. Level of social deprivation was quantified using the Townsend Deprivation Index (TDI) [16].

Three months after discharge from PICU, in the course of an interview about their memory for events during their admission [4], each child had completed a post-traumatic stress screening questionnaire. One parent or primary carer (referred to as ‘parent’ throughout the text for clarity) also completed a post-traumatic stress screen at this point, as well as a brief measure of symptoms of anxiety and depression, but these data have not been published previously.

As the 1-year anniversary of discharge approached, permission was sought from the family’s general practitioner to re-contact the family by post. If the questionnaires were not returned after a second mailing, participants were given an opportunity either to complete them over the telephone or in person, when the child was next due to be reviewed in the outpatient clinic. All families were offered referral on for further support if their scores were above clinical cut-off at 12 months.

Psychological measures (see online supplement for further information)

The questionnaires used were selected on the basis of their brevity, as well as their validity, in order to minimise the burden on the participants in the clinical setting where full psychiatric interviews are impractical.

-

1.

Children’s Revised Impact of Event Scale (CRIES-8): Children’s post-traumatic stress symptoms were measured using the eight-item version of the Children’s Revised Impact of Event Scale (CRIES-8). This is a self-report measure developed for use with children aged between 7 and 18 years, with established reliability and validity [17]. A total score of 17 or more has been found to classify correctly over 80 % of children with a diagnosis of PTSD [18].

-

2.

SPAN: The SPAN is a brief post-traumatic stress symptom screener for adults, made up of four items (‘Startle’, ‘Physiological Arousal’, ‘Anger’ and ‘Numbness’) from the Davidson Trauma Scale [19], which is reported to have as good psychometric properties as other longer screening instruments [20]. Scores of 5 or more have been shown to classify correctly 88 % of diagnosed cases of PTSD [21].

-

3.

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale: The HADS is a self-report questionnaire for use with adults with good internal consistency and reliability [22], made up of two separate scales, one measuring anxiety and the other measuring depression. Scores of 11 or more on either scale indicate a ‘moderate/severe’ level of symptoms, which is regarded as clinically significant [23].

Statistical analyses

Non-parametric statistics were used, as not all variables were normally distributed. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to make paired comparisons for the same participant at the two screening timepoints. Differences between subgroups were analysed using the Mann–Whitney U test for continuous variables and Pearson’s χ2 or Fisher’s exact test for categorical data. Finally Spearman rank correlations were computed to examine the association between parents’ and children’s post-traumatic stress scores. Analyses were performed using the SPSS 16.0 software (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

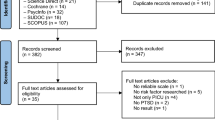

Recruitment and retention (see Fig. 1)

Of the 132 families approached to take part in the original study [4], 102 (77 %) agreed to take part. Families of surviving children (n = 99) were re-contacted for the present study and of these, 81 (82 %) provided some follow-up data at 12 months. Given the focus of this study, statistical analyses were confined to the 66 child–parent pairs [50 % of original potential sample (n = 132) but 67 % of those approached (n = 99)] who provided complete post-traumatic stress data at both timepoints. Statistical comparisons showed no systematic differences, regarding baseline patient characteristics, between the children in recruited and non-recruited families, or between those who stayed in the study and those who dropped out between 3 and 12 months (see Tables A and B in the online supplement). Sample characteristics of the 66 child–parent pairs with complete post-traumatic stress data are given in Table 1.

Prevalence of post-traumatic stress symptoms

Children

Children’s group median (range) score on the CRIES-8 did not change significantly between the timepoints studied [10 (0–26) at 3 months vs. 7.5 (0–33) at 12 months, p = 0.218]. Similarly there was little difference between the proportion of children scoring in the clinical range at 3 months and 12 months [20 (32 %) vs. 17 (26 %), p = 0.561]. On an individual level, however, seven children scoring below cut-off at 3 months, later scored in the clinical range at 12 months (Fig. 2).

Proportions of children (n = 66) and parents (n = 66) scoring above cut-off on post-traumatic stress screening measures at 3 months and 12 months following the child’s discharge from the PICU. *Symptomatic defined as score above recommended clinical cut-off: for children ≥17 on the CRIES-8; for adults ≥5 on the SPAN

Parents

Parents’ group median (range) score on the SPAN fell significantly between 3 months and 12 months from 4 (0–16) to 2 (0–16), p = 0.017. In total 28 (42 %) parents scored in the clinical range at 3 months. This number fell to 18 (27 %) at 12 months (p = 0.067). However, these group level analyses concealed individual differences in the opposite direction. There were eight examples of parents who had scored below the clinical range at 3 months who later scored above cut-off at 12 months (Fig. 2).

Child–parent pairs

The proportions of families affected by significant levels of post-traumatic stress at 3 months and 12 months are illustrated in Fig. 3. Clinically significant symptom levels were evident in at least one member of 29 (44 %) child–parent pairs a year after discharge, and there were nine examples of families where both the child and the parent were significantly symptomatic. In total, post-traumatic stress scores increased over time in the cases of 26 children and 18 parents.

The ‘worst thing’ about the PICU experience

In the process of completing the post-traumatic stress screening instruments, children and parents were asked to state the ‘worst thing’ that they had experienced in relation to the child’s intensive care admission. Responses to this question were examined for the 20 children and 28 parents scoring in the clinical range at 3 months.

Children

Many children reported a specific distressing event on PICU as the worst thing they remembered, such as waking up and not knowing where their parents were (n = 5); vomiting (n = 3); having hallucinations on PICU (n = 2) and choking on the ventilator tube (n = 1). Some could not isolate a particular event, describing the whole PICU experience as traumatic (n = 3). However, in 7 (35 %) cases children specified an event which had occurred outside the PICU as the worst part of their experience. This was most commonly related to the accident or deterioration that had precipitated their admission.

Parents

In comparison only 4 (14 %) parents gave a pre-admission event as the most traumatic. The majority stated that the time on PICU was the most stressful from their perspective, with 13 parents citing a particular low point (such as seeing the child attached to the machines for the first time, receiving a life-threatening diagnosis or realising their child could die) and 11 parents responding to the question in general terms, such as ‘the whole thing’ or ‘everything—I will never forget it’.

Associations with post-traumatic stress status 12 months after discharge

Children (see Table 2)

Children scoring above cut-off at 12 months had higher post-traumatic stress scores at 3 months and higher mortality risk (PIM) scores on admission. Their status was not however associated with any demographic variables or with parental psychopathology at 3 months. Also, although the child’s report of delusional experiences during admission was associated with post-traumatic stress symptoms at 3 months in the original study [4], this association was not significant at 12 months, in this sub-sample.

Parents (see Table 3)

Parents scoring above cut-off at 12 months had higher anxiety scores at 3 months and were more likely to have had their child admitted non-electively. Furthermore, at 3 months their children had reported higher post-traumatic stress scores, and in particular more symptoms of avoidance, than the children of parents who scored in the normal range for post-traumatic stress symptoms 12 months after discharge.

The correlation between child and parent post-traumatic stress scores was significant at 3 months (r = 0.32, p = 0.008), but not at 12 months (r = 0.01, p = 0.920).

Anxiety and depression in parents

The numbers of parents scoring in the ‘moderate/severe’ range on the HADS (subscale score ≥ 11) for anxiety were 19 (29 %) at 3 months, and 17 (26 %) at 12 months. For depression, the numbers were 5 (8 %) and 4 (6 %), respectively.

Discussion

This study a group of children, whose recollections of PICU and post-traumatic stress symptoms at 3 months have been reported on previously [4], were followed up together with their parents, 12 months after discharge.

Rates of post-traumatic stress were similar to those found in other studies [3, 5, 6]. However, although parents’ and children’s scores were significantly associated at 3 months, as has been found in another cross-sectional study [3], this association was no longer significant 12 months after discharge, suggesting that different factors influenced their psychological outcome as time went on. Also, in relation to the change in symptoms over time, whilst there was a significant reduction in parents’ group median score over the year, the same was not true for children. This finding is consistent with those of a small number of studies of children followed up for a year or more after injury, which have shown strikingly little change in rates of post-traumatic stress levels [24, 25]. Furthermore, although the qualitative findings relating to parents’ experiences of PICU were similar to those described by others [5], children were more likely than their parents to describe events leading up to admission as the most traumatic.

The finding that psychological variables were more strongly associated with subsequent distress than demographic or medical variables was also consistent with a recent review of post-traumatic stress in paediatric intensive care patients [7]. This suggests that, in terms of predicting psychological outcome, subjective experience is more important than objective aspects of the child’s condition—i.e. how something is experienced is more of a predictor of future distress than what is experienced. In a similar finding Balluffi et al. [5] found that whereas parents’ perception of the risk that the child would die was associated with the development of post-traumatic stress symptoms, objective measures of severity of the child’s illness were not.

Furthermore, although usually only 15 % of PTSD cases have a delayed onset [26], in this sample nearly half of the participants scoring in the clinical range 12 months after discharge had become newly symptomatic between the two timepoints studied. It is not clear why an increase in post-traumatic stress symptoms was reported by so many in this study, although it has been suggested that in the case of serious injury, the initial need to focus on physical recovery can delay the full appreciation of the psychological impact of a traumatic experience [27]. Another possible explanation could be that families were distressed by other traumatic events occurring during the year after discharge, as has been found with children and parents after cancer diagnosis [28, 29].

Finally, the finding that parents whose children were more avoidant at 3 months, reported more post-traumatic stress symptoms at a year suggests that, as has been reported elsewhere [30], parents’ psychological reactions after trauma may sometimes be shaped by their child’s reactions, rather than the other way round, as is more commonly assumed. This finding might in part explain the effect of the ‘COPE’ programme [31], which encourages parents to help children process their experiences on PICU soon after they are discharged and has been associated with long-term psychological benefits for mothers and children.

Limitations

The original recruitment rate was high, at 77 %, but there was a significant amount of attrition. Nevertheless, the proportion of participants retained in this study by 12 months was still higher than rates reported in comparable studies in other paediatric and intensive care settings [5, 6, 13, 31, 32], indicating relatively good representation of a population that is difficult to recruit and retain in research studies. Also the attrition did not appear to lead to any systematic differences in the main sample characteristics (see Table B in the online supplement).

The lack of health-related measures beyond the time of admission is a limitation of this study and the findings may not be directly applicable to the families of children aged under 7 years or those with learning difficulties. Also given the documented properties of the screening instruments used, the true rate of full PTSD in this sample is likely to be closer to one in five.

Clinical implications

This study confirms that, as has been found with adult intensive care survivors [33], the fact that a child has required critical care treatment is associated with an elevated risk of developing post-traumatic stress symptoms. The findings suggest that patients and relatives should be monitored for these symptoms for some time after discharge.

Ideally such monitoring would take place in dedicated follow-up clinics, although currently such clinics are more prevalent in adult settings [34, 35]. Evidence for the value of systematic monitoring of groups judged to be at risk of PTSD has recently been demonstrated by the success of a proactive ‘screen and treat’ approach following the terrorist attacks in London in 2005 [36].

In terms of implications for preventative work, the findings support the use of interventions designed to promote communication between parents and children, such as the ‘COPE’ programme [31] or developmentally appropriate storybooks [37] which may prove as beneficial as the ICU diaries offered to adult patients [38, 39].

Conclusion

This study highlights the need for ongoing psychological monitoring of families in the year following a child’s intensive care treatment and confirms that they are a vulnerable population with respect to the risk of developing post-traumatic stress symptoms. Levels of anxiety and depression reported by the parents in this sample a 12 months after discharge were also noteworthy, at approximately double community rates [40].

The findings also suggest that delayed post-traumatic reactions may be commoner than previously thought in this population and that the impact of the PICU experience is not necessarily the same for the parent and child, particularly in the longer term. By employing screening instruments such as those described, health professionals caring for these families after discharge will be in a better position to identify and offer support to those suffering persistent or delayed psychological reactions to their traumatic experiences.

References

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (2005) Post-traumatic stress disorder: national clinical practice guideline no 26. Gaskell and the British Psychological Society, London

Brewin CR (2003) Posttraumatic stress disorder: malady or myth? Yale University Press, New Haven

Rees G, Gledhill J, Garralda ME, Nadel S (2004) Psychiatric outcome following paediatric intensive care unit (PICU) admission: a cohort study. Intensive Care Med 30:1607–1614

Colville G, Kerry S, Pierce C (2008) Children’s factual and delusional memories of intensive care. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 177:976–998

Balluffi A, Kassam-Adams N, Kazak A, Tucker M, Dominguez T, Helfaer M (2004) Traumatic stress in parents admitted to the pediatric intensive care unit. Pediatr Crit Care Med 5:547–553

Bronner MB, Peek N, Knoester H, Bos AP, Last BF, Grootenhuis MA (2010) Course and predictors of posttraumatic stress disorder in parents after pediatric intensive care treatment of their child. J Pediatr Psychol 35:966–974

Davydow DS, Richardson LP, Zatzick DF, Katon WJ (2010) Psychiatric morbidity in pediatric critical illness survivors: a comprehensive review of the literature. Arch Pediatr Adolesc 164:377–383

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (2009) Rehabilitation after critical illness: national clinical practice guideline no 83. NICE, London

Griffiths J, Fortune G, Barber V, Young JD (2007) The prevalence of post traumatic stress disorder in survivors of ICU treatment: a systematic review. Intensive Care Med 33:1506–1518

Azoulay E, Pochard F, Kentish-Barnes N, Chevret S, Aboab J, Adrie C, Annane D, Bleichner G, Bollaert PE, Darmon M, Fassier T, Galliot R, Garrouste-Orgeas M, Goulenok C, Goldgran-Toledano D, Hayon J, Jourdain M, Kaidomar M, Laplace C, Larché J, Liotier J, Papazian L, Poisson C, Reignier J, Saidi F, Schlemmer B, FAMIREA Study Group (2005) Risk of post-traumatic stress symptoms in family members of intensive care unit patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 171:987–994

Ward-Begnoche W (2007) Posttraumatic stress symptoms in the pediatric intensive care unit. J Spec Pediatr Nurs 12:84–92

Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, Hughes M, Nelson CB (1995) Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry 52:1048–1060

Bryant RA, Salmon K, Sinclair E, Davidson P (2007) The relationship between acute stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder in injured children. J Trauma Stress 20:1075–1079

Chapman C, Mills K, Slade T, McFarlane AC, Bryant RA, Creamer M, Silove D, Teesson M (2011) Remission from post-traumatic stress disorder in the general population. Psychol Med 14:1–9

Pearson G, Stickley J, Shann F (2001) Calibration of the paediatric index of mortality in UK paediatric intensive care units. Arch Dis Child 84:125–128

Townsend P, Phillimore P, Beattie A (1988) Health and deprivation: inequality and the North. Croom Helm, Andover

Yule W (1997) Anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress in childhood. In: Sclare I (ed) Child psychology portfolio. NFER-Nelson, Windsor, pp 35–38

Perrin S, Meiser-Stedman R, Smith P (2005) The children’s revised impact of event scale (CRIES): validity of a screening instrument for PTSD. Behav Cogn Psychother 33:487–498

Davidson JR, Book SW, Colket JT, Tupler LA, Roth S, David D, Hertzberg M, Mellman T, Beckham JC, Smith RD, Davison RM, Katz R, Feldman ME (1997) Assessment of a new self-rating scale for post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychol Med 27:153–160

Brewin CR (2005) Systematic review of screening instruments for adults at risk of PTSD. J Trauma Stress 18:53–62

Meltzer-Brody S, Churchill E, Davidson JRT (1999) Derivation of the SPAN, a brief diagnostic screening test for post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychiatry Res 8:63–70

Bjelland I, Dahl AA, Haug TT, Neckelmann D (2002) The validity of the hospital anxiety and depression scale: an updated literature review. J Psychosom Res 52:69–77

Zigmond AS, Snaith RP (1983) The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 67:361–370

Gillies ML, Barton J, DiGallo A (2003) Follow-up of young road accident victims. J Trauma Stress 16:523–526

Landolt MA, Vollrath M, Timm K, Gnehm HE, Sennhauser FH (2005) Predicting posttraumatic stress symptoms in children after road traffic accidents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 44:1276–1283

Andrews B, Brewin CR, Philpott R, Stewart L (2007) Delayed onset post-traumatic stress disorder: a systematic review of the evidence. Am J Psychiatry 164:1236–1319

Carty J, O’Donnell ML, Creamer M (2006) Delayed-onset PTSD: a prospective study of injury survivors. J Affect Disord 90:257–261

Jurbergs N, Long A, Ticona L, Phipps S (2009) Symptoms of posttraumatic stress in parents of children with cancer: are they elevated relative to parents of healthy children? J Pediatr Psychol 34:4–13

Currier JM, Jobe-Shields LE, Phipps S (2009) Stressful life events and posttraumatic stress symptoms in children with cancer. J Trauma Stress 22:28–35

McFarlane AC (1987) Family functioning and over-protection following a natural disaster: the longitudinal effects of post-traumatic morbidity. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 21:210–218

Melnyk BM, Alpert-Gillis L, Feinstein NF, Crean HF, Johnson J, Fairbanks E, Small L, Rubenstein J, Slota M, Corbo-Richert B (2004) Creating opportunities for parent empowerment: program effects on the mental health/coping outcomes of critically ill young children and their mothers. Pediatrics 113:597–607

Meiser-Stedman R, Yule W, Smith P, Glucksman E, Dalgleish T (2005) Acute stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder in children and adolescents involved in assaults or motor vehicle accidents. Am J Psychiatry 162:1381–1383

O’Donnell ML, Creamer M, Holmes AC, Ellen S, McFarlane AC, Judson R, Silove D, Bryant RA (2010) Posttraumatic stress disorder: does admission to intensive care unit increase risk? J Trauma 69:627–632

Colville GA, Cream PR, Kerry SM (2010) Do parents benefit form the offer of a follow-up appointment after their child’s admission to intensive care? An exploratory randomised controlled trial. Intensive Crit Care Nurs 26:146–153

Griffiths JA, Barber VS, Cuthbertson BH, Young JD (2006) A national survey of intensive care follow-up clinics. Anaesthesia 61:950–955

Brewin CR, Scragg P, Robertson M, Thompson M, d’Ardenne P, Ehlers A, Psychosocial Steering Group, London Bombings Trauma Response Programme (2008) Promoting mental health following the London bombings: a screen and treat approach. J Trauma Stress 21:3–8

Colville G (2012) Paediatric intensive Care. The Psychologist 25:206–209

Knowles RE, Tarrier N (2009) Evaluation of the effect of prospective patient diaries on emotional well-being in intensive care unit survivors: a randomized controlled trial. Crit Care Med 37:184–191

Jones C, Bäckman C, Capuzzo M, Egerod I, Flaatten H, Granja C, Rylander C, Griffiths RD, RACHEL group (2010) Intensive care diaries reduce new onset post traumatic stress disorder following critical illness: a randomized, controlled trial. Crit Care 14:R168

Crawford JR, Henry JD, Crombie C, Taylor EP (2001) Brief report: normative data for the HADS from a large non-clinical sample. Br J Clin Psychol 40:429–434

Acknowledgments

We thank Sally Hall for her help in drafting the manuscript. This study was supported by a Leading Practice Through Research Award granted to the first author by The Health Foundation, UK.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Colville, G., Pierce, C. Patterns of post-traumatic stress symptoms in families after paediatric intensive care. Intensive Care Med 38, 1523–1531 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-012-2612-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-012-2612-2