Abstract

Purpose

Despite the concerns about older adults’ overall quality of life during the COVID-19 pandemic, they often demonstrated better resilience, adaptability, and subjective well-being (SWB) than younger individuals. However, longer-term trends remain unclear. This study aims to describe older adults' trajectories in SWB dimensions before, during, and after the pandemic spanning 2017–2022.

Methods

This study used piecewise growth curve analysis on a subsample of the Swiss Household Panel to investigate the population-average (n individuals = 3086; n = observations = 13,780) trajectories of SWB dimensions and stress among adults aged 65 and older between 2017 and 2022. We also tested whether these trajectories differed by age, gender, and household income.

Results

Life satisfaction and positive affect remained stable among older people during the pandemic (2019–2021) but declined after. Negative affect increased during the pandemic and decreased afterward, while stress levels increased slightly before and significantly after the pandemic. The trajectories did not differ by gender or household income, but the oldest-old (> 75-year-old) had a more significant decline in positive affect and life satisfaction pre-pandemic (2017–2019) and stress during the pandemic (2020–2021).

Conclusion

Research shows that older adults possess adaptation skills and emotional competencies, which enable them to navigate pandemic challenges. However, we show that the post-pandemic era presents more substantial challenges for this older population, who perhaps face more difficulties adapting to the new uncertain post-pandemic world. Further research needs to examine if these findings replicate in other contexts, for instance, where pandemic containment measures have been more stringent.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic, a major 21st-century event, globally impacted everyone [1], particularly older adults who faced higher risks from the virus [2]. Despite their vulnerability and the need for strict social distancing, studies have shown that older adults have impressively adapted to the disruptions caused by the pandemic [3, 4].

Studies tend to show relative stability in life satisfaction [5, 6] and mental health [7], with no significant divergence from the trends observed before the pandemic. However, there is also some evidence of increased negative affect among older people [8]. This is in contrast to younger people who tended to report an increase in stress [9], depressive and anxiety symptoms [10], and declines in life satisfaction [11] and negative affect [12]. This suggests better adaptation among older people compared with younger age groups in the early stages of the pandemic [13]. Nonetheless, the evidence on longitudinal trajectories starting pre-pandemic is limited [14, 15]. Hence, it is difficult to determine whether the changes observed during the pandemic continue a longer trend [14, 15]. There is also inconsistency in evidence on subjective well-being (SWB) trajectories later during the pandemic, with some studies finding a deterioration in different dimensions of SWB in the later stages of the pandemic [16] and worsened depression and anxiety [6, 15]. Other studies found stability in stress, negative affect, and depressive symptoms with positive affect [17]. Post-pandemic evidence seems virtually lacking.

Our study aims to describe population-average trajectories of SWB and stress of older adults living independently between 2017 and 2022. To further explore potential heterogeneity in the trajectories, we compare the ‘young-old’ (65 to 74 years) and the ‘oldest-old’ (75 years and above).

Method

Data, sample

This study draws on longitudinal data from six waves (2017–2022) of the Swiss Household Panel-SHP [18, 19]. This nationally representative survey interviewed all household members older than 14 years of age from a random sample of private households in Switzerland since 1999. Questionnaires were administered mainly by computer-assisted telephone interviewing (CATI) (96–98%), with the rest of the participants using computer-assisted web interviewing (CAWI).

The analytical sample includes a subsample of SHP participants who were at least 65 years old in 2019 and had at least one valid measure of SWB between 2017 and 2022 (n individuals = 3086; n observations = 13,780). Table 1 provides participants’ descriptive information.

Among the entire sample, 49.6% had no missing information across the dependent variables, meaning they had completed information across all six waves. Additionally, 12.6% had only one measure of dependent variables across the time points (out of six possible). The missing data pattern was monotone, with the number of participants having missing outcomes increasing by 6.0–7.5% each observation year (2017–2022) (see Table 2).

Measures

Dependant variables

Two components of SWB—positive affect and life satisfaction (PALS) and negative affect (NA)—were derived by summing up the relevant items ranging from 0 to 10. A higher score indicated greater satisfaction in each life domain and more frequent positive and negative affect. Table 3 details these measures. The psychometric properties of both measures were extensively examined [20], showing high internal consistency and scalar measurement invariance across time, age, sexes, and survey modes.

Positive affect and life satisfaction (PALS) comprised six items: (1) life satisfaction, (2) satisfaction with health, (3) satisfaction with personal, social, and family relationships, (4) satisfaction with leisure time activities [21, 22]; and two positive affect items [23] (5) the level of energy and optimism and (6) the level of joy. The internal consistency was strong, ranging between 0.75 and 0.76 across study years. The PALS score could range from 0 to 60.

Negative affect (NA) [23] comprised four items that assessed the level of four negative emotions—anger, sadness, worry/anxiety, and depression. The internal consistency was strong, ranging between 0.75 and 0.77 across study years. The NA could range from 0 to 40.

Stress [24] was measured using a single item that assessed an individual’s stress level, ranging from 0–“never” to 5–“very often.”

Covariates

Sociodemographic indicators were included as potential effect modifiers of the age-SWB association to examine differences in the population-average trajectories across subgroups of the population: gender (1 = male; 2 = female), age groups (aged 65–74 years; those aged 75 years and above), and equivalized household income in quartiles.

Statistical analysis

The longitudinal population-average trajectories in SWB in 2017–2022 were described using piecewise growth curve analysis. This approach accounts for the multilevel structure of longitudinal data, where occasion-specific measurements are nested within individuals, and incomplete or unbalanced data, taking advantage of maximum likelihood estimation [25]. Our model included both fixed effects and random effects. Fixed effects represent the population’s average effect of time while controlling for age (and age2). Random effects include information about variance around the starting point of the trend (an intercept) and the trend itself (a slope).

Time is conceptualized as four separate periods (slopes), representing an overall trend between 2017 and 2022. The four slopes were (1) pre-pandemic—2017–2019; (2) into-pandemic—2019–2020; (3) pandemic—2020–2021; and (4) out-of-pandemic—2021–2022. This allowed us to directly compare the change in different periods. For instance, we could test whether a potential decline in SWB before the pandemic equaled a potential improvement in SWB post-pandemic using a Wald test, which formulates the null hypothesis that these two slopes equal zero (i.e., slope2017–2019 − slope2021–2022 = 0).

We also compared the trajectories of SWB between men and women, age groups (65–75 vs > 75-year-old), and quartiles of the equivalised household income by allowing the slopes to vary by these groups. We did this by including interaction terms between the age groups and slopes (e.g., gender*slope2017–2019, gender*slope2019–2020, gender*slope2020-2021, gender*slope2021–2022), and testing for differences with the Wald test (at p < 0.05). We further investigated the differences by running pairwise comparisons of estimated marginal means. All models were also controlled for the survey mode (CATI, CAWI).

Results

Positive affect and life satisfaction (PALS)

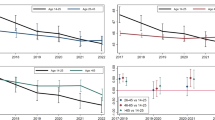

PALS somewhat decreased before the pandemic (−0.31, −0.41 to −0.21), was stable into (−0.01, −0.20 to 0.17) and during the pandemic (0.03, −0.17 to 0.24), then it declined out-of-pandemic (−0.81, −1.04 to −0.58) (see Fig. 1 Panel A; based on model estimates from Table 4). The oldest respondents expressed a greater decline in PALS between 2017 and 2019 (−0.57, −0.74 to −0.40) than the young (−0.20, −0.32 to −0.09). We found no evidence for differential trajectories across gender and income.

When examining the items separately (Table 4; Fig. 2 Panel A), satisfaction levels with relationships and joy improved during the pandemic. At the same time, they were stable for life satisfaction, energy, and optimism, but all declined after the pandemic. The drop in relationship satisfaction was greater out-of-pandemic (−0.18, −0.25 to −0.12) than the increase reported during the pandemic (0.07, 0.01–0.13). Satisfaction with health decreased, on average, both during (−0.07, −0.14 to 0.00) and out-of-pandemic (−0.13, −0.20 to −0.05).

Negative affect (NA)

The average levels of NA were stable before (−0.07, −0.19 to 0.04) and into-pandemic (−0.18, −0.40 to 0.04) but increased drastically during the pandemic (1.09, 0.84–1.33) and declined out-of-pandemic (1.09, 0.84–1.33) (Fig. 1 Panel B; based on model estimates from Table 4). We found no evidence for differential trajectories across gender, age, and income.

The average frequency of anger, sadness, and worry increased during the pandemic and declined equivalently out-of-pandemic. For instance, for worry, the increase in 2020–2021 was 0.33 (0.23–0.43), and the subsequent decline (2021–2022) was −0.39 (−0.50 to −0.29) (Fig. 2 Panel B).

Stress

The average stress levels marginally increased two years before the pandemic (0.02, 0.00–0.04). Subsequently, they were relatively stable into- (−0.10, −0.05 to 0.03) and during the pandemic (0.02, −0.02 to 0.07) and increased again out-of-pandemic (0.06, 0.02–0.11) (Fig. 1 Panel C; based on model estimates from Table 4). The oldest-old respondents had a greater increase in stress between 2020 and 2021 (0.09, 0.01–0.16) than young-old (−0.02, −0.07 to 0.03). We found no evidence for differential trajectories across gender and income.

Discussion

The post-pandemic decline in PALS and increase in stress are multifaceted. While older adults possess relatively good competencies for adjusting to short-term events, they struggle with long-term stressors [13]. Thus, the prolonged nature of the pandemic’s impact may have contributed to the worsening of SWB among older individuals. Additionally, the rise in societal ageism [26] during the pandemic might have contributed to this decline in PALS and increase in stress, as negative stereotypes and perceptions about older people have intensified, harming their quality of life [27, 28]. Moreover, despite the heightened focus on older adults as a vulnerable group during the pandemic, they faced significant challenges (loss of close relationships, enforced isolation, and reduced social interactions), which exacerbated feelings of loneliness and isolation. These experiences have negatively affected their mental health [28] and may have enduring impacts on their PALS.

The escalating negative emotions during the 2020–2021 pandemic align with some previous findings of increased depression and anxiety [15] but not with others, suggesting that older adults experienced less negative affect [12, 29]. However, we observed a post-pandemic decline in negative emotions to pre-pandemic levels. This pattern, evident in specific feelings like anger, sadness, and worry, may stem from pandemic-related stressors such as health concerns, isolation, and frustration over restrictions. With the pandemic’s decrease in threat, these negative emotions have reverted to baseline, indicating a direct emotional response to the pandemic’s challenges and subsequent adaptation.

Most older adults were resilient early in the COVID-19 pandemic [e.g. 3, 4, 13, 14, 28]. However, our study revealed that they faced increasing difficulties over time, affecting their SWB and stress levels. While changes were minor but statistically significant, their broad impact is notable due to the many older adults affected.

Despite many strengths, our study presents some limitations. The most notable one is the potential bias resulting from missing information. As in most observational studies [30], there was a dropout, likely among those with poor physical and/or cognitive health and limited economic resources. We were also unable to explore the sensitivity of our findings to survival bias. Moreover, our study did not include participants in assisted living or care facilities who had not had the same experience of the pandemic as their counterparts living at home. In the Swiss context, many individuals in medical and social care establishments were isolated during the pandemic due to the prohibition of family or friend visits, as in hospitals. Thus, both isolation and lack of social relationships negatively affect SWB trajectories [28]. Their experience was very different from that of people living at home. During the pandemic, Switzerland introduced, compared with other countries, a semi-lockdown with only open shops, but non-essential shops and public places were closed. However, outdoor activities were permitted, provided that no more than five people were present and that physical distance was maintained. The whole population, especially the older adults and those at risk were encouraged to stay at home. However, thanks to private initiatives, it was possible for vulnerable people to ask for help, particularly for shopping, if they did not want to take the risk of going out. The possibility of asking for help and seeing up to five other people, even if it was outside, encouraged some older people to continue social activities.

Furthermore, the measure of socioeconomic inequality in our study, the equivalized household income, did not adequately consider accumulated wealth. It is possible that some individuals with extensive wealth were classified as having low income, making the comparison groups highly heterogeneous. This could have led to diluting any differences in trajectories across income quartiles.

To conclude, our findings emphasize that despite largely resilient adaptation to the pandemic’s stressors, the post-pandemic period presented, somewhat unexpectedly, significant challenges for older adults regardless of gender, age group, or financial resources.

Appendix

See Tables 1, 2, 3, 4 and Fig. 2.

Data availability

The “Living in Switzerland Waves 1-24 (including a long file) + Covid 19” data supporting this research's findings are available from SwissUbase to the scientific community upon submission of a data request application (https://www.swissubase.ch). Study data has already been de-identified.

References

Settersten RA Jr, Bernardi L, Härkönen J, Antonucci TC, Dykstra PA, Heckhausen J et al (2020) Understanding the effects of Covid-19 through a life course lens. Adv Life Course Res 45:100360. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.alcr.2020.100360

Shahid Z, Kalayanamitra R, McClafferty B, Kepko D, Ramgobin D, Patel R et al (2020) COVID-19 and older adults: what we know. J Am Geriatr Soc 68(5):926–929. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.16472

Minahan J, Falzarano F, Yazdani N, Siedlecki KL (2021) The COVID-19 pandemic and psychosocial outcomes across age through the stress and coping framework. Gerontologist 61(2):228–239. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnaa205

Fuller HR, Huseth-Zosel A (2021) Lessons in resilience: initial coping among older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. Gerontologist 61(1):114–125. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnaa170

Kivi M, Hansson I, Bjälkebring P (2021) Up and about: older adults’ well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic in a Swedish longitudinal study. J Gerontol B 76(2):e4–e9. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbaa084

Wettstein M, Nowossadeck S, Vogel C (2022) Well-being trajectories of middle-aged and older adults and the corona pandemic: no “COVID-19 effect” on life satisfaction, but increase in depressive symptoms. Psychol Aging 37(2):175–189. https://doi.org/10.1037/pag0000664

Van Tilburg TG, Steinmetz S, Stolte E, Van der Roest H, de Vries DH (2021) Loneliness and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: a study among Dutch older adults. J Gerontol B 76(7):e249–e255. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbaa111

Macdonald B, Hülür G (2021) Well-being and loneliness in Swiss older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic: the role of social relationships. Gerontologist 61(2):240–250. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnaa194

Birditt KS, Turkelson A, Fingerman KL, Polenick CA, Oya A (2021) Age differences in stress, life changes, and social ties during the COVID-19 pandemic: implications for psychological well-being. Gerontologist 61(2):205–216. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnaa204

Feliciano L, Johanson KA, Okun ML, Walden A (2022) Impacts of the coronavirus pandemic on the emotional and physical health of older adults compared with younger cohorts. Clin Gerontol 45(1):45–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/07317115.2021.1966561

Bidzan-Bluma I, Bidzan M, Jurek P, Bidzan L, Knietzsch J, Stueck M et al (2020) A Polish and German population study of quality of life, well-being, and life satisfaction in older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Psych 11:585813

Young NA, Waugh CE, Minton AR, Charles ST, Haase CM, Mikels JA (2021) Reactive, agentic, apathetic, or challenged? Aging, emotion, and coping during the COVID-19 pandemic. Gerontologist 61(2):217–227. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnaa196

Knepple Carney A, Graf AS, Hudson G, Wilson E (2021) Age moderates perceived COVID-19 disruption on well-being. Gerontologist 61(1):30–35. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnaa106

Sterina E, Hermida AP, Gerberi DJ, Lapid MI (2022) Emotional resilience of older adults during COVID-19: a systematic review of studies of stress and well-being. Clin Gerontol 45(1):4–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/07317115.2021.1928355

Zaninotto P, Iob E, Demakakos P, Steptoe A (2022) Immediate and longer-term changes in the mental health and well-being of older adults in England during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Psychiatr 79(2):151–159. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.3749

Hansen T, Sevenius Nilsen T, Knapstad M, Skirbekk V, Skogen J, Vedaa Ø et al (2022) Covid-fatigued? A longitudinal study of Norwegian older adults’ psychosocial well-being before and during early and later stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur J Ageing 19(3):463–473. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-021-00648-0

Fields EC, Kensinger EA, Garcia SM, Ford JH, Cunningham TJ (2022) With age comes well-being: older age associated with lower stress, negative affect, and depression throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. Aging Ment Health 26(10):2071–2079. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2021.2010183

Tillmann R, Voorpostel M, Antal E, Dasoki N, Klaas H, Kuhn U et al (2022) The Swiss Household Panel (SHP). Jahr für Natl Stat 242(3):403–420. https://doi.org/10.1515/jbnst-2021-0039

SHP Group (2023) Living in Switzerland Waves 1–23 + Covid 19 data (6.0.0) [dataset]. FORS data service. FORS, Lausanne. https://doi.org/10.48573/642z-p311

Gondek D, Garzón EG, Sánchez-Mira N, Vandecasteele L, Steinmetz S, Voorpostel M (2024) Going beyond the single item: deriving and evaluating a composite subjective wellbeing measure in the Swiss Household Panel. FORS Lausanne. Retrived from osfio/tjrwq2023. Accessed 5 Feb 2024

Diener ED, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, Griffin S (1985) The satisfaction with life scale. J Pers Assess 49(1):71–75

Diener E (1984) Subjective well-being. Psychol Bull 95(3):542–575. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.95.3.542

Scherer KR, Wranik T, Sangsue J, Tran V, Scherer U (2004) Emotions in everyday life: probability of occurrence, risk factors, appraisal and reaction patterns. Soc Sci Inf 43:499–570. https://doi.org/10.1177/0539018404047

Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R (1983) A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav 24:386–396

Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS (2002) Hierarchical linear models: applications and data analysis methods, 2nd edn. Sage Publications, Newbury Park

Ayalon L, Chasteen A, Diehl M, Levy BR, Neupert SD, Rothermund K et al (2021) Aging in times of the COVID-19 pandemic: avoiding ageism and fostering intergenerational solidarity. J Gerontol Psychol Sci 76(2):e49–e52. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbaa051

Brinkhof LP, Murre JMJ, de Wit S, Krugers HJ (2023) Ridderinkhof K (2023) Changes in perceived ageism during the COVID-19 pandemic: impact on quality of life and mental well-being among Dutch adults aged 55 and older. Aging Ment Health. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2205832

Kornadt AE, Albert I, Hoffmann M, Murdock E, Nell J (2021) Ageism and older people’s health and well-being during the COVID-19-pandemic: the moderating role of subjective aging. Eur J Ageing 18(2):173–184. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-021-00624-8

Carstensen LL, Shavit YZ, Barnes JT (2020) Age advantages in emotional experience persist even under threat from the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol Sci 31(11):1374–1385. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797620967261

Banks J, Muriel A, Smith JP (2011) Attrition and health in ageing studies: evidence from ELSA and HRS. Longit Life Course Stud. https://doi.org/10.14301/llcs.v2i2.115

Acknowledgements

This study used data collected by the Swiss Household Panel (SHP), which is based at FORS, the Swiss Centre of Expertise in the Social Sciences. The Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF) finances the project.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Lausanne. This work was supported by Schweizerischer Nationalfonds zur Förderung der Wissenschaftlichen Forschung, 408040_210152.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

VAR wrote the main text of the manuscript. DG carried out the analyses, prepared the figures and tables, and wrote the methodological section. MV directed the overall project. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

This paper uses data from SHP Group. (2023). Living in Switzerland Waves 1–23 + Covid-19 data (6.0.0) [dataset]. FORS data service FORS. https://doi.org/10.48573/642z-p311. The Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF) finances the project. [Swiss National Science Foundation (NRP80, grant number 408040 210152)].

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Valérie-Anne, R., Dawid, G. & Marieke, V. Changes in subjective well-being and stress of older adults before, during and after the COVID-19 pandemic: a longitudinal study in Switzerland. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-024-02706-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-024-02706-1