Abstract

Purpose

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought significant distress on not only the physical health but also mental health of individuals. The present study investigated the direct and indirect effects from COVID-19 distress to suicidality via psychosocial and financial well-being among young people.

Methods

This cross-sectional survey recruited 1472 Hong Kong young people via random sampling in 2021. The respondents completed a phone survey on COVID-19 distress, the four-item Patient Health Questionnaire and items on social well-being, financial well-being, and suicidality. Structural equation modeling (SEM) was conducted to examine the direct and indirect effects of COVID-19 distress on suicidality via psychosocial and financial well-being.

Results

The direct effect of COVID-19 distress on suicidality was not significant (β = 0.022, 95% CI − 0.097–0.156). The total indirect effect from COVID-19 distress to suicidality was significant and positive (αβγ = 0.150, 95% CI = 0.085–0.245) and accounted for 87% of the total effect (B = 0.172, 95% CI = 0.043–0.341). There were significant specific indirect effects via social well-being and psychological distress, and financial well-being and psychological distress.

Conclusion

The present findings support different pathways from COVID-19 distress to suicidality via functioning in different domains among young people in Hong Kong. Measures are needed to ameliorate the impact on their social and financial well-being to reduce their psychological distress and suicidality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, there have been widespread concerns about its effects on suicidality [1, 2]. In a previous meta-analysis of 54 studies among 308,596 individuals [1], the results showed increased event rates for suicide ideation (10.81%), suicide attempts (4.68%), and self-harm (9.63%) during the COVID-19 pandemic compared to pre-pandemic studies. A recent longitudinal study examined the mental health trajectories during the first 6 weeks of pandemic lockdown in 3,077 UK adults and found an increased incidence of suicidal ideation among young adults [3]. In contrast, another longitudinal study found no difference in the prevalence of suicidal ideation among 1,103 adults in Spain between the pre-lockdown period (June 17, 2019 to March 14, 2020) and the pandemic lockdown period (May 21, 2020 to June 30, 2020) [4]. In Hong Kong, though the suicide rate slightly decreased from 13.4 (per 100,000) in 2019 to 12.1 (per 100,000) in 2020 [5], a rebound of the suicidal rate was observed in 2021. Specifically, there has been a surge of youth suicide cases amid pandemic. The Coroner's Court reported a suicide rate of 1.7 (per 100,000) for youth in 2021, reaching a historical high. In fact, young adults (especially students) reported to have severe mental disorders during the pandemic, while most of them feel stressful dealing with academic challenges and future job prospects [6]. A research conducted during COVID-19 on young adults found an association between suicidal thoughts and perceived support from family, friends, or school [7]. Owing to the equivocal nature of the evidences, more empirical studies are required to clarify the effects of COVID-19 on suicidality in young adults.

Deterioration in psychosocial and financial well-being associated with the COVID-19 pandemic may exacerbate the suicide risks [1, 2]. Specifically, suicidal ideation or behaviors during the COVID-19 have been associated with various social factors (loneliness and living alone), psychological factors (anxiety, depression, and insomnia), and financialFootnote 1 factors (financial strain, housing instability, and unemployment) in recent studies [8,9,10,11]. Findings from a systematic review identified the prevalence of stress, anxiety, and depression as a result of the pandemic to be 29.6%, 31.9%, and 33.7%, respectively [12]. For instance, isolation and quarantine may impose negative effects on people’s mental health [13]. There is increasing evidence that heightened feelings of loneliness could influence psychological problems during the COVID-19 pandemic [14, 15]. For instance, loneliness was correlated with depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder in a cross-sectional survey of the Spanish population [16]. In addition, people who perceived themselves as having low social support were at high risk of developing psychiatric disorders. In a study of US citizens, stay-at-home order status was associated indirectly with suicide risk through thwarted belongingness [15], reflecting both loneliness and lack of social support [17].

The unique combination of economic and social impacts resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic has aggravated the occurrence of suicidal ideation and behavior [15, 18, 19], though specific impacts of financial hardship remain undetermined. Research found that continued insufficiency in income especially among low-income individuals during the pandemic has affected their mental health and life satisfaction [20]. Similarly, Stevenson, Wakefield [21] found that COVID-19-related financial distress predicted negative psychological outcomes (loneliness, anxiety, and depression) which in turn were associated with greater suicidal risks. The findings replicate the pernicious effect of financial stress on mental health across different age groups and national contexts, including Hong Kong, in previous research [22,23,24,25]. In addition, these studies have shown that deterioration in financial well-being is related to suicidal thoughts/behavior via these psychological variables. The above findings suggest that deterioration in psychosocial and financial well-being may mediate the association between COVID-19 distress and suicidality. The pathways by which COVID-19 distress leads to suicidality are complex and are currently not well understood. To the best of our knowledge, no empirical studies have simultaneously evaluated these indirect effects in a multivariate model. Structural equation modeling is a latent variable modeling technique that allows rigorous examination of the inter-relationships among COVID-19 distress, suicidality, and well-being in different domains.

In light of the research gaps, the first objective of the present study was to examine the relationships between COVID-19 distress and suicidality in a large sample of young adults in Hong Kong. The second objective of the study aimed to evaluate the potential mediating role of social well-being, financial well-being, and psychological distress in the relationship between COVID-19 distress and suicidality. The third objective of the study was to compare the indirect effects using social well-being, financial well-being, and psychological distress as different mediators between COVID-19 distress and suicidality. There were three hypotheses in this study relating to youth and young adults (18–36 years). In Hypothesis 1, COVID-19 distress would be significantly and negatively associated with suicidality. In Hypothesis 2, both social and financial well-being as well as psychological distress would mediate the effect of COVID-19 distress on suicidality. In Hypothesis 3, COVID-19 distress would be significantly and negatively associated with social well-being, financial well-being while positively associated with psychological distress. It is hoped that this study provides empirical findings for policy makers to prevent suicide during large-scale epidemics.

Materials and methods

Study design and procedures

The present study was cross-sectional in nature and recruited a large sample of young people via random sampling in a telephone survey. The inclusion criteria were an age between 18 and 36 years old, residence in Hong Kong, and an ability to understand spoken Cantonese. A random sample of 125,746 mobile phone numbers was generated using mobile number prefixes that were published by the Office of the Communications Authority in Hong Kong. The telephone survey was administered by the Social Science Research Centre in the University of Hong Kong. The potential respondents were contacted by interviewers using the computer-aided telephone interviewing system from 6:30 to 10:30 pm on weekdays. The telephone interviewers were fluent in Cantonese and received prior trainings for conducting the interviews. The participants provided oral informed consent before completing an interview on a self-report questionnaire in around 5 min. Participation in the survey was strictly voluntary and all information provided by the participants was kept entirely confidential. Contact information of local community resources was provided to the respondents if they felt distressed anytime during the interview. Ethical approval for this project was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee of the University of Hong Kong prior (Reference number: EA1709039).

Participants

The telephone survey was conducted between 2nd August and 17th December 2021 and successfully completed 1,501 interviews. The overall response rate of the phone survey was 68.9% with 544 refusals by respondents and 132 uncompleted interviews. A total of 29 participants were aged below 18 years old and were excluded in the present study. The final sample of 1472 respondents consisted of 762 males and 710 females with a mean age of 26.3 years (SD = 3.8). Half of them belonged to young adults (50.7%) with an age of 26 to 36 years and the other half belonged to youths (49.3%) with an age of 18 to 25 years. The majority of the sample attained tertiary education level (92.4%) and were working (82.3%). The respondents showed an average level of COVID-19 distress (Mean = 2.83, SD = 1.21). Nearly one-third (29.7%) of the respondents perceived the COVID-19 distress to be severe or very severe. Half (51.6%) of the respondents encountered distressing issues or life difficulties in the past 4 weeks. The questionnaire also consisted of items on social well-being, financial well-being, psychological distress, and suicidality.

Measures

COVID-19 distress

COVID-19 distress was evaluated by a single item “To what extent have you been distressed by the COVID-19 pandemic?” on a five-point Likert format from 1 = “not at all” to 5 = “severe distress”.

Social well-being

Social well-being was measured by three self-constructed items that inquired the levels of well-being of the respondents in the social life with classmates or colleagues or friends, with spouse or partner, and with family members over the past 4 weeks. The items were answered on a five-point Likert format from 0 = “severe distress” to 4 = “no interference at all”. In the present sample, the three-item self-constructed instrument on social well-being showed satisfactory composite reliability (ω = 0.76).

Financial well-being

The Financial Well-Being (FWB) Scale was developed by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau in the United States. This scale was a validated ten-item measure of respondents’ sense of financial situation over the past 4 weeks [26] and have been adopted in the Chinese context [27]. Because of practical constraint in administering the telephone interviews, the present study assessed financial well-being via a random subset of three items from the FWB Scale. Example items were “I am just getting by financially” and “I am concerned that the money I have or will save won’t last”. The items were answered on a five-point Likert format from 0 = “describes me completely” to 4 = “does not describe me at all”. The three-item shortened version of the FWB Scale showed satisfactory composite reliability (ω = 0.78) in the present sample.

Psychological distress

Psychological distress was evaluated using the brief four-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-4) [28]. This scale combines the PHQ-2 with the two items from the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale as a measure of anxiety and depressive symptoms over the past 2 weeks. Example items are “feeling down, depressed or hopeless”, and “feeling nervous, anxious or on edge”. The items were answered on a four-point Likert format from 0 = “not at all” to 3 = “nearly every day”. The PHQ-4 has been validated in the Chinese context [29]. The composite score has a theoretical range from 0 to 12, with higher scores denoting greater degrees of psychological distress. In the present sample, the PHQ-4 showed good composite reliability (ω = 0.80).

Suicidality

Suicidality was assessed by three binary items on suicide ideation, suicide attempt, and deliberate self-harm. The respondents were asked whether they have considered suicide, attempted suicide, or injured themselves intentionally in the past 12 weeks.

Statistical analysis

Preliminary item screening found that most of the items on social well-being, financial well-being, and psychological distress displayed substantial floor effects, with 30.4–62.4% of the respondents endorsing the minimum category. Given the deviation from normal distribution, the ten items were treated as ordinal categorical items together with the three binary items on suicidality [30]. The descriptive statistics and polychoric correlations of the main study variables were obtained via preliminary analysis. Missing data were minimal in the dataset except for the partner distress item, where 23% of the respondents (N = 340) did not answer because of a lack of spouse or partner. Missing data were handled using full information maximum likelihood under the missing-at-random assumption [31]. The data analyzed in this manuscript are available in this paper in the form of a supplementary file.

Factorial and construct validity of the measurement scales were evaluated by confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). The 13 items on social well-being, financial well-being, psychological distress, and suicidality were analyzed in a 4-factor CFA model under the robust weighted least square estimator in Mplus 8.4 [32]. Problematic items that did not load substantially (λ < 0.50) on the factor would be removed from the CFA model [33]. Model fit was appraised based on the following criteria on the fit indices [34]: comparative fit index (CFI) ≥ 0.95, Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) ≥ 0.95, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) ≤ 0.06, and standardized root mean square residuals (SRMR) ≤ 0.06. Residual covariance was added between two PHQ-4 items in the CFA model based on theoretical justifications. Composite reliability of the latent factors was evaluated via McDonald Omega (ω) with values of at least 0.75 indicating good reliability. The inter-factor correlations in the CFA model were obtained as a preliminary inspection of the relationships among the study variables. Statistical significance was set at the 0.05 in the present study.

Structural equation modeling (SEM) was conducted to evaluate the direct and indirect effects of COVID-19 distress on suicidality via social well-being, financial well-being, and psychological distress under the robust weighted least square estimator. The COVID-19 distress and latent factor of suicidality were the primary predictor and outcome variable in the model, respectively. The latent factors of social and financial well-being were posited as parallel mediators followed by psychological distress as a sequential mediator and all three latent factors were measured by their observed items. The SEM model included the following variables as the control variables: gender, age, working status, and presence/absence of distressing issues in the past 4 weeks.

The model estimated the direct and indirect effects of COVID-19 distress on suicidality via different pathways of well-being. The total indirect effect was decomposed into specific indirect effects via social well-being, financial well-being, and psychological distress. To account for the likely skewed distribution, the indirect effects were estimated using 10,000 bootstrap draws. The estimated effects were regarded as statistically significant if the 95% confidence interval (CI) excluded zero. R-square denoted the proportion of explained variance of the dependent variables. Sensitivity analysis was performed by estimating the SEM model across gender groups (males and females) and age groups (youths and young adults).

Results

Sample profiles and item correlations

Table 1 reports the descriptive statistics and polychoric correlations of the measurement items in the sample. They reported moderate levels of social and financial well-being and an average total PHQ-4 score of 2.72 (SD = 2.42). The proportion of respondents with suicidal ideation, suicide attempt, and deliberate self-harm was 10.1%, 1%, and 4.1%, respectively. COVID-19 distress was significantly and negatively correlated with the items on social and financial well-being (r = − 0.13 to − 0.27, p < 0.01) and was significantly and positively correlated with the measurement items on psychological distress and suicidality (r = 0.10–0.20, p < 0.01) except for suicide attempt (r = 0.11, p = 0.14). Moderate to strong inter-item correlations were found among the measurement items for social well-being (r = 0.49–0.57, p < 0.01), financial well-being (r = 0.47–0.56, p < 0.01), psychological distress (r = 0.43–0.73, p < 0.01), and suicidality (r = 0.70–0.71, p < 0.01).

CFA model results

As Table 2 shows, the four-factor CFA model provided an acceptable approximate fit to the data with CFI and TLI > 0.95, and RMSEA and SRMR < 0.06. Addition of the residual covariance (r = 0.42, p < 0.01) between the two PHQ-4 items on anxiety symptoms significantly improved the model fit of the CFA model (Δχ2 = 54.6, df = 1, p < 0.01). All factor loadings were found to be significant and substantial (λ = 0.64–0.86, p < 0.01). Social and financial well-being were negatively and moderately correlated with psychological distress and suicidality (r = − 0.39 to − 0.57, p < 0.01). There was a positive and moderate correlation between social and financial well-being (r = 0.51, p < 0.01) and a positive and strong correlation between psychological distress and suicidality (r = 0.70, p < 0.01).

SEM model results

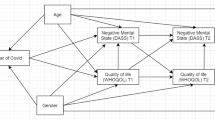

As Table 2 shows, the SEM model provided an adequate fit to the data with CFI and TLI ≥ 0.95, and RMSEA and SRMR < 0.06. Figure 1 depicts the unstandardized path coefficients from COVID-19 distress to suicidality via social well-being, financial well-being, and psychological distress in the model. In the SEM model, all of the factor loadings were significant and substantial (λ = 0.64–0.89, p < 0.01). Female respondents were significantly associated with higher levels of social well-being, financial well-being, and psychological distress (β = 0.16 to 0.24, p < 0.01) but not COVID-19 distress and suicidality (p = 0.16–0.78). Age was not significantly associated with any of the main study variables (p = 0.13–0.88). Working status was significantly associated with better financial well-being (β = 0.26, p < 0.01) but not with other variables (p = 0.17 – 0.72). Respondents with recent distressing issues were significantly associated with lower levels of social and financial well-being (β = − 0.32 to -0.51, p < 0.01) and higher levels of COVID-19 distress and psychological distress (β = 0.35 to 1.00, p < 0.01).

Unstandardized path coefficients from COVID-19 distress to suicidality via social well-being, financial well-being, and psychological distress in the structural equation model. PHQ Patient Health Questionnaire; SWB social well-being, FWB financial well-being; paths involving social well-being and financial well-being are marked in red and blue, respectively. Effects from COVID-19 distress to PHQ-4 and from PHQ-4 to suicidality are marked in green. Significant paths among the main study variables are bolded. Factor loadings of the latent factors are shown in orange. Standard errors are shown in parentheses. For simplicity, non-significant effects from the control variables to main study variables are omitted in the figure

COVID-19 distress significantly and negatively predicted social and financial well-being (β = − 0.16 to − 0.23, p < 0.01) but not psychological distress (β = 0.02, p = 0.64). Both social and financial well-being negatively predicted psychological distress (β = − 0.16 to -0.48, p < 0.01). Suicidality was negatively linked with social well-being (β = − 0.34, p < 0.05) and positively linked with psychological distress (β = 0.58, p < 0.01) but not financial distress (β = − 0.08, p = 0.45). The model explained 11.8%, 11.2%, 45.2%, and 56.9% of the variance of latent factors of social well-being, financial well-being, psychological distress, and suicidality, respectively. Sensitivity analysis revealed similar results consistent patterns of results across gender groups (males and females) and age groups (youths and young adults).

Direct, indirect, and total effects of COVID-19 distress on suicidality

Table 3 lists the unstandardized direct, indirect, and total effects of COVID-19 distress on suicidality via the mediators in the SEM model. COVID-19 distress did not show a significant direct effect on suicidality (B = 0.022, 95% CI = − 0.097 to 0.156). The total indirect effect from COVID-19 distress to suicidality via the mediators was significant and positive (αβγ = 0.150, 95% CI = 0.085–0.245), accounting for 87.2% of the total effect (B = 0.172, 95% CI = 0.043–0.341). Three of the five specific indirect effects were found to be statistically significant: (1) via social well-being only (red paths); (2) via social well-being and psychological distress (red + green paths); and ( 3) via financial well-being and psychological distress (blue + green paths). The total indirect effect from COVID-19 to suicidality was significant via social well-being (αβγ = 0.102, 95% CI = 0.053 to 0.177) but not via financial well-being (αβγ = 0.039, 95% CI = − 0.006 to 0.095).

Discussion

This study aimed to explore the relationship between COVID-19 distress, social and financial well-being, psychological distress, and suicidality among young people. The CFA results supported adequate construct validity and reliability for the four latent factors. Despite the significant and positive total effect, our SEM results did not find COVID-19 distress to be directly associated with suicidality. COVID-19 distress showed significant indirect effects on suicidality through social well-being, financial well-being, and PHQ-4. To our knowledge, our study was the first to simultaneously investigate the mediating role of social and financial well-being in the relationship between COVID-19 distress and suicidality.

Our results showed that COVID-19 distress was significantly and negatively associated with social well-being and financial well-being. Also, COVID-19 distress was significantly and positively associated with psychological distress. Recent literature has pointed out that the pandemic had adverse effects on the economy, social, and psychological well-being of people [35]. Our findings provided evidence that the pandemic could create financial, social, and psychological distress for young people in Hong Kong. On the other hand, our findings did not find COVID-19 distress to be directly associated with suicidality. In fact, existing literature of suicidal behaviors during emerging viral disease outbreaks, including COVID-19, were relatively scarce [36]. No strong evidence has supported a direct relationship between COVID-19 and suicidality.

Although no direct relationship was found between COVID-19 distress and suicidality, the present study identified a number of mediators. Previous research suggested that psychosocial effect of the pandemic was a main risk factor for suicidal behaviors [36]. Our findings provided evidence that the relationship between COVID-19 distress and suicidality was mediated by social and psychological well-being. Individuals who were distressed by the pandemic were more likely to experience social distress, which made them more susceptible to suicidal ideation or suicide attempt. In Hong Kong, various social distancing measures such as compulsory quarantine, active surveillance, and contact tracing have been implemented for an extended period of time. In line with previous linkage between social distress and psychological distress [37,38,39], these social distancing measures are likely to result in social isolation and loneliness, which in turn contribute to suicidal thoughts and behavior [40, 41]. Our findings revealed that higher COVID-19 distress was indirectly associated with higher levels of suicidality via lower social well-being and higher psychological distress sequentially.

In addition, our findings suggested higher levels of COVID-19 distress were indirectly associated with higher levels of suicidality via lower financial well-being and increased psychological distress sequentially. This result is consistent with previous findings where COVID-19-related financial distress predicted negative psychological outcomes and suicidal thoughts/behavior [21]. The pandemic brought global employment problems and also changes in the labor market. Lower skilled workers from the retail, accommodation, food services, and tourism industries faced high risks of unemployment [42]. In addition, there were extra costs of living during the COVID-19 pandemic in terms of acquiring a list of protective equipment such as N95 face masks, face shields, medical gloves, and personal hygiene necessities such as disinfectant, alcohol, and hand sanitizers. The financial cost was especially higher given the shortage of supplies during the first few waves of COVID-19 outbreaks [43]. It is not uncommon for financially vulnerable individuals to suffer from depression and anxiety especially among the low-income group [42].

The COVID-19 pandemic imposed a significant distress on people’s daily life. The study findings offer insights onto the relationship between COVID-19 distress and suicidality. Our results suggest that measures to improve social and financial well-being may reduce psychological distress and suicidality. There are important implications for policies and community interventions to promote mental health and suicide prevention under large-scale epidemics. Policies that could help reduce social and financial distress of young people should be implemented, monetary support especially to the low-income group would be conducive in maintaining the mental health of the young adults. As the pandemic continues to be stabilized, it is important for the governments to gradually relax the social distancing measures in the process toward resumption of normal life routine. The unemployment rate among the young adults is especially high during the COVID-19 due to the unfavorable economic condition (Office of the Government Economist, 2021). Subsidies and job opportunities may be provided to young adults who are financially vulnerable.

The present study was subject to a number of limitations. First, the present study measured respondents’ suicidality over a longer timeframe of 12 weeks than the assessment timeframe (2–4 weeks) of social well-being, financial well-being, and psychological distress. There might as well be reciprocal effects from suicidality measures to the recent well-being measures. Given the cross-sectional design, the present study could not infer causal directions from the findings among the study variables. Suicidality measures should be assessed across different time points as in Wu et al. [44]. Further longitudinal studies with repeated assessments are needed to track the changes in various domains of well-being of the respondents and their temporal associations with suicidality measures over different phases of the COVID-19 pandemic. Second, despite the random sampling through the phone survey, participants self-selected to participate in the survey and there was potential selection and response bias. It was theoretically plausible that the more distressed individuals were more inclined to take part in the survey.

Third, the present study measured COVID-19 distress using only a single item and could not account for the reliability of this predictor. Future research could adopt validated pandemic-specific distress scales such as the Fear of COVID-19 Scale [45] and Coronavirus Anxiety Scale [46] to examine pandemic-specific psychological responses. Similarly, the present study only assessed financial well-being via three out of the ten items from the Financial Well-Being Scale. Despite the good reliability for the three-item shortened version, the shortened version might not adequately assess the financial well-being as compared to the original ten-item version. Such a discrepancy could plausibly explain the lesser mediating role for financial well-being than social well-being in the SEM model. Fourth, this study evaluated the COVID-19 distress on suicidality among a large sample of young adults in Hong Kong aged 18 to 36 years. Cautions are warranted in generalizing the results to other age groups and cultural contexts. Future studies are needed to examine the effect of COVID-19 distress on suicidality in samples of adolescents and older adults.

Fifth, history of mental disorders, concerns over COVID-19, and positive diagnosis of COVID-19 have been associated with suicidal ideation or behaviors during the COVID-19 [9, 47]. Since the present study did not include assessments on these factors, this could introduce omitted variable and confounding biases to the results. Last but not least, our SEM model only explained less than 10% of the variances of social well-being and financial well-being in the Hong Kong adults under COVID-19. This suggests the need of including other relevant variables such as quarantine experience, social isolation, and lifestyle factors to enhance the explanatory power of the model.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Notes

FWB = financial well-being; PHQ = Patient Health Questionnaire; CFA = confirmatory factor analysis; CFI = comparative fit index; TLI = Tucker–Lewis index,

RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation, SRMR = standardized root mean square residuals; SEM = structural equation modeling; CI = confidence interval.

References

Dubé JP, Smith MM, Sherry SB, Hewitt PL, Stewart SH (2021) Suicide behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic: a meta-analysis of 54 studies. Psychiatry Res 301:113998–113998

Moutier C (2020) Suicide prevention in the COVID-19 Era: transforming threat into opportunity. JAMA Psychiat 78(4):433

O’Connor RC, Wetherall K, Cleare S, McClelland H, Melson AJ, Niedzwiedz CL, O’Carroll RE, O’Connor DB, Platt S, Scowcroft E, Watson B, Zortea T, Ferguson E, Robb KA (2021) Mental health and well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic: longitudinal analyses of adults in the UK COVID-19 mental health & wellbeing study. Br J Psychiatry 218(6):326–333

Ayuso-Mateos JL, Morillo D, Haro JM, Olaya B, Lara E, Miret M (2021) Changes in depression and suicidal ideation under severe lockdown restrictions during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in Spain: a longitudinal study in the general population. Epidemiol Psychiat Sci 30:e49–e49

Rise in youth suicide amid pandemic, expert warns (2022). The Standard, September 12,

Ahorsu DK, Pramukti I, Strong C, Wang HW, Griffiths MD, Lin CY, Ko NY (2021) COVID-19-related variables and its association with anxiety and suicidal ideation: differences between international and local university students in Taiwan. Psychol Res Behav Manag 14:1857–1866. https://doi.org/10.2147/prbm.S333226

Pramukti I, Strong C, Sitthimongkol Y, Setiawan A, Pandin MGR, Yen CF, Lin CY, Griffiths MD, Ko NY (2020) Anxiety and suicidal thoughts during the COVID-19 pandemic: cross-country comparative study among indonesian, Taiwanese, and Thai university students. J Med Internet Res 22(12):e24487. https://doi.org/10.2196/24487

Elbogen EB, Lanier M, Blakey SM, Wagner HR, Tsai J (2021) Suicidal ideation and thoughts of self-harm during the COVID-19 pandemic: the role of COVID-19-related stress, social isolation, and financial strain. Depress Anxiety 38(7):739–748

Papadopoulou A, Efstathiou V, Yotsidi V, Pomini V, Michopoulos I, Markopoulou E, Papadopoulou M, Tsigkaropoulou E, Kalemi G, Tournikioti K (2021) Suicidal ideation during COVID-19 lockdown in Greece: prevalence in the community, risk and protective factors. Psychiatry Res 297:113713

Antonelli-Salgado T, Monteiro GMC, Marcon G, Roza TH, Zimerman A, Hoffmann MS, Cao B, Hauck S, Brunoni AR, Passos IC (2021) Loneliness, but not social distancing, is associated with the incidence of suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 outbreak: a longitudinal study. J Affect Disord 290:52–60

Killgore WD, Cloonan SA, Taylor EC, Fernandez F, Grandner MA, Dailey NS (2020) Suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic: the role of insomnia. Psychiatry Res 290:113134

Salari N, Hosseinian-Far A, Jalali R, Vaisi-Raygani A, Rasoulpoor S, Mohammadi M, Rasoulpoor S, Khaledi-Paveh B (2020) Prevalence of stress, anxiety, depression among the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Glob Health 16(1):57. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-020-00589-w

Canas-Simião H, Reis C, Carreiras D, Espada-Santos P, Paiva T (2022) Health-related behaviors and perceived addictions: predictors of depression during the COVID lockdown. J Nerv Ment Dis 210(8):613–621. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0000000000001503

Allan NP, Volarov M, Koscinski B, Pizzonia KL, Potter K, Accorso C, Saulnier KG, Ashrafioun L, Stecker T, Suhr J, Allan DM (2021) Lonely, anxious, and uncertain: critical risk factors for suicidal desire during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry Res 304:114144–114144

Gratz KL, Tull MT, Richmond JR, Edmonds KA, Scamaldo KM, Rose JP (2020) Thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness explain the associations of COVID-19 social and economic consequences to suicide risk. Suicide Life-Threat Behav 50(6):1140–1148

González-Sanguino C, Ausín B, Castellanos MÁ, Saiz J, López-Gómez A, Ugidos C, Muñoz M (2020) Mental health consequences during the initial stage of the 2020 Coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19) in Spain. Brain Behav Immun 87:172–176

Van Orden KA, Cukrowicz KC, Witte TK, Joiner TE (2012) Thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness: construct validity and psychometric properties of the interpersonal needs questionnaire. Psychol Assess 24(1):197–215

Bryan CJ, Bryan AO, Baker JC (2020) Associations among state-level physical distancing measures and suicidal thoughts and behaviors among US adults during the early COVID-19 pandemic. Suicide Life-Threat Behav 50(6):1223–1229

Fitzpatrick KM, Harris C, Drawve G (2020) How bad is it? Suicidality in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic. Suicide Life-Threat Behav 50(6):1241–1249

Vicerra P (2022) Mental stress and well-being among low-income older adults during COVID-19 pandemic. Asian J Social Health Behav 5(3):101–107. https://doi.org/10.4103/shb.shb_110_22

Stevenson C, Wakefield JRH (2021) Financial distress and suicidal behaviour during COVID-19: Family identification attenuates the negative relationship between COVID-related financial distress and mental Ill-health. J Health Psychol 26(14):2665–2675

Assari S (2018) Suicide attempts in michigan healthcare system. Racial DifferencesBrain sci 8(7):124

Fiksenbaum L, Marjanovic Z, Greenglass E, Garcia-Santos F (2017) Impact of economic hardship and financial threat on suicide ideation and confusion. J Psychol 151(5):477–495

Wang Y, Sareen J, Afifi TO, Bolton S-L, Johnson EA, Bolton JM (2015) A population-based longitudinal study of recent stressful life events as risk factors for suicidal behavior in major depressive disorder. Arch Suicide Res 19(2):202–217

Chung GK, Strong C, Chan YH, Chung RY, Chen JS, Lin YH, Huang RY, Lin CY, Ko NY (2022) Psychological distress and protective behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic among different populations hong kong general population, taiwan healthcare workers, and taiwan outpatients. Front Med 9:800962. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2022.800962

Howat-Rodrigues ABC, Laks J, Marinho V (2021) Translation, cross-cultural adaptation, and psychometric properties of the Brazilian Portuguese version of the consumer financial protection bureau financial well-being scale. Trends Psychiat Psychother 43:134–140. https://doi.org/10.47626/2237-6089-2020-0034

Xie X, Xie M, Jin H, Cheung S, Huang C-C (2020) Financial support and financial well-being for vocational school students in China. Child Youth Ser Rev. 118:105442. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105442

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Lowe B (2009) An ultra-brief screening scale for anxiety and depression: The PHQ-4. Psychos (Washington, DC) 50(6):613–621

Xiong N, Fritzsche K, Wei J, Hong X, Leonhart R, Zhao X, Zhang L, Zhu L, Tian G, Nolte S, Fischer F (2014) Validation of patient health questionnaire (PHQ) for major depression in Chinese outpatients with multiple somatic symptoms: A multicenter cross-sectional study. J Affect Disord 174:636–643

Rhemtulla M, Brosseau-Liard PÉ, Savalei V (2012) When can categorical variables be treated as continuous? a comparison of robust continuous and categorical sem estimation methods under suboptimal conditions. Psychol Meth 17(3):354–373

Little RLA, Rubin DB (2019) Statistical analysis with missing data (3rd edition). John Wiley & Sons, 793

Muthén LK, Muthén BO (2017) Mplus: Statistical analysis with latent variables: User’s guide (Version 8). Muthén & Muthén

Howard MC (2016) A Review of exploratory factor analysis decisions and overview of current practices: what we are doing and how can we improve? Int J Human-Comp Int 32(1):51–62

Hu L-t, Bentler PM (1999) Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Model 6(1):1–55

Gómez-Salgado J, Palomino-Baldeón JC, Ortega-Moreno M, Fagundo-Rivera J, Allande-Cussó R, Ruiz-Frutos C (2022) COVID-19 information received by the Peruvian population, during the first phase of the pandemic, and its association with developing psychological distress: Information about COVID-19 and distress in Peru. Med (Baltimore) 101(5):e28625–e28625

Leaune E, Samuel M, Oh H, Poulet E, Brunelin J (2020) Suicidal behaviors and ideation during emerging viral disease outbreaks before the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic rapid review. Prev Med 141:106264–106264

Adamczyk K, Segrin C (2015) Direct and indirect effects of young adults’ relationship status on life satisfaction through loneliness and perceived social support. Psychol Belg 55(4):196–211. https://doi.org/10.5334/pb.bn

Safipour J, Schopflocher D, Higginbottom G, Emami A (2011) The mediating role of alienation in self-reported health among Swedish adolescents. Vul groups incl 2(1):5805. https://doi.org/10.3402/vgi.v2i0.5805

Zhang B, Gao Q, Fokkema M, Alterman V, Liu Q (2015) Adolescent interpersonal relationships, social support and loneliness in high schools: mediation effect and gender differences. Soc Sci Res 53:104–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2015.05.003

Beutel ME, Klein EM, Brähler E, Reiner I, Jünger C, Michal M, Wiltink J, Wild PS, Münzel T, Lackner KJ, Tibubos AN (2017) Loneliness in the general population: prevalence, determinants and relations to mental health. BMC Psychiatry 17(1):97. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-017-1262-x

McClelland H, Evans JJ, Nowland R, Ferguson E, O’Connor RC (2020) Loneliness as a predictor of suicidal ideation and behaviour: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. J Affect Disord 274:880–896. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.05.004

Choi YJ, Kühner S, Shi S-J (2022) From “new social risks” to “COVID social risks”: the challenges for inclusive society in South Korea, Hong Kong, and Taiwan amid the pandemic. Policy Soc 41(2):260–274

Siu JYm, (2021) Health inequality experienced by the socially disadvantaged populations during the outbreak of COVID-19 in Hong Kong: an interaction with social inequality. Health Soc Care Community 29(5):1522–1529. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.13214

Wu C-Y, Lee M-B, Huong PTT, Chan C-T, Chen C-Y, Liao S-C (2022) The impact of COVID-19 stressors on psychological distress and suicidality in a nationwide community survey in Taiwan. Sci Rep 12(1):2696. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-06511-1

Chang K-C, Hou W-L, Pakpour AH, Lin C-Y, Griffiths MD (2022) Psychometric testing of three COVID-19-related scales among people with mental illness. Int J Ment Heal Addict 20(1):324–336. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-020-00361-6

Lee SA (2020) Coronavirus anxiety scale: a brief mental health screener for COVID-19 related anxiety. Death Stud 44(7):393–401. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2020.1748481

Killgore WD, Cloonan SA, Taylor EC, Dailey NS (2020) Loneliness: a signature mental health concern in the era of COVID-19. Psychiatry Res 290:113117

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the members at The Hong Kong Jockey Club Centre for Suicide Research and Prevention, The University of Hong Kong for various roles such as project coordination, data cleaning, and fruitful discussions of the results. We would like to express our gratitude to the Social Science Research Centre for their help in data collection and all respondents for their participation in the phone survey.

Funding

This study was supported by the Hong Kong Jockey Club Charities Trust for the OpenUp online emotional support program, the General Research Fund grants (GRF/HKU 17606521, 17608522), and a Collaborative Research Fund (C7151-20G) of the Research Grants Council. The funding organization had no role in the study design, collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, or the writing of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Wendy So: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Writing – original draft. Ted Fong: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Formal analysis, Data Curation, Writing – original draft, Visualization. Bowie Woo: Investigation, Writing – original draft, Project administration. Paul Yip: Conceptualization, Validation, Resources, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

So, W.W.Y., Fong, T.C.T., Woo, B.P.Y. et al. Psychosocial and financial well-being mediated the effects of COVID-19 distress on suicidality: a serial mediation model among Hong Kong young adults. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 59, 165–174 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-023-02501-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-023-02501-4