Abstract

National mental health surveys play a critical role in determining the prevalence of mental disorders in a population and informing service planning. However, current surveys have important limitations, including the exclusion of key vulnerable groups and increasing rates of non-response. This review aims to synthesise information on excluded and undersampled groups in national mental health surveys. We conducted a targeted review of nationally representative adult mental health surveys performed between 2005 and 2019 in high-income OECD countries. Sixteen surveys met our inclusion criteria. The response rate for included surveys ranged between 36.3% and 80.0%. The most frequently excluded groups included people who were homeless, people in hospitals or health facilities and people in correctional facilities. Males and young people were the most commonly underrepresented groups among respondents. Attempts to collect data from non-responders and excluded populations were limited, but suggest that mental health status differs among some of these cohorts. The exclusion of key vulnerable groups and high rates of non-response have important implications for interpreting and using the results of national mental health surveys. Targeted supplementary surveys of excluded or hard-to-reach populations, more inclusive sampling methodologies, and strategies aimed at improving response rates should be considered to strengthen the accuracy and usefulness of survey findings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Nationally representative mental health surveys play a critical role in providing quality data to help understand and track the mental health of a population. Most contemporary mental health surveys collect data on more than disorder prevalence alone to gain better insight into the impacts of mental disorders and the types of interventions or services required. For example, surveys conducted as part of the World Health Organization (WHO)’s World Mental Health Survey (WMH) Initiative also collect data on disease burden, relevant risk factors, comorbidities, service use and unmet treatment needs.[1].

On a broad scale, global estimates of the burden of mental and other disorders rely on population-based prevalence surveys as a key input. At a national level, these surveys help to shape the public narrative around mental health within a country and play a fundamental role in influencing mental health policy, planning and funding [2]. In fact, planning and costing tools such as the mental health module within the OneHealth systems planning tool (OHT) [3] and Australia’s National Mental Health Service Planning Framework (NMHSPF) [4, 5] draw heavily on estimates generated by population-based prevalence surveys to model mental health care resource requirements.

While such mental health surveys provide critical insight into the mental health status and needs of a population, it is important to recognise their limitations. These include the ongoing exclusion of key vulnerable groups through sampling methodologies and growing rates of non-response. To date, there has been no review synthesising information on the impacts of non-response or excluded populations in large mental health surveys. Understanding these systematically excluded subpopulations is critical to identifying potential underreporting of population mental health needs and to ensure equity of access and tailored service planning for the highest needs groups.

This review aims to (1) identify which groups are commonly excluded from large mental health surveys in high-income OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) countries, (2) identify survey response rates and describe the characteristics of non-responders, and (3) describe any efforts to examine, supplement or adjust for the impacts of non-response and missing or underrepresented populations.

Methods

We conducted a targeted literature review of national mental health surveys to extract detail on survey sampling methods by drawing on previous systematic reviews of prevalence data.

Survey search strategy and inclusion criteria

The Global Burden of Disease Study 2019 (GBD 2019) Data Input Sources Tool [6] was used to screen data sources for prevalence of mental disorders in high-income OECD countries published from 2005 onwards. The GBD inputs are obtained through a systematic review of studies and data sources on the prevalence and burden of mental disorders from 204 countries between 1990 and 2019 [7]. Additional information on the GBD review methodology is available online [7].

From this list, sources were included for further consideration if they described a population-based mental health survey that:

-

Ended between January 2005 and December 2019, inclusive; included a nationally representative sample of adults; surveyed multiple classes of mental disorders (e.g. depressive disorders, anxiety disorders, substance use disorders, eating disorders, personality disorders, conduct or impulse control disorders, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, autism spectrum disorders, psychotic disorders); and

-

was completed as either a stand-alone mental health survey or conducted as part of a general health survey.

-

Sources were excluded from further review if the survey they described:

-

was limited to only one gender;

-

focused on adults in a narrow age cohort only (e.g. young adults, older adults);

-

was a follow-up of a previously surveyed cohort and therefore not a random sample from the general population;

-

had specific aims other than determining prevalence of mental disorders that otherwise restricted the eligibility criteria;

-

focused exclusively on one class of mental disorder, e.g. depressive disorders only;

-

restricted the sample to one region within a country;

-

sampled populations across multiple countries as part of the same survey.

A list of relevant surveys was then compiled from the included GBD sources. Where multiple iterations of a survey were conducted for different years, only the most recent version included in GBD was selected.

Search for published survey methods

A Google search was then conducted from May to September 2021 using the name (or the title of the GBD source where no name was given) and year of each survey as search terms to collect academic and grey literature sources associated with each survey, such as methodology reports and results studies. The first 50 search results were scanned for publications that described the survey in their methodology or findings. Where websites or webpages devoted to listing or archiving a survey’s publications were identified in the search results, these were thoroughly checked. Forward and backward snowballing [8] was conducted using references from the original GBD publication(s) and Google search results as the start set. Forward snowballing was performed using the online citation index scite [9], while backward snowballing was performed by hand until saturation was reached (i.e. no new relevant sources were identified). Google searching and snowballing was preferred to a search of scientific databases given that a large proportion of the data of interest lay in grey literature. Government and non-government reports, government webpages, journal articles and manuscripts were reviewed. Online translations of non-English sources were considered for review if they could be verified by a fluent language reader. News articles, commentaries, blog posts, abstracts only and non-government webpages were excluded.

A full-text review of all relevant publications was conducted to identify the primary source of data for the survey methodology. Where multiple publications described the methodology in comparable detail, the earliest published or available resource was selected. Supplementary sources were also included where they provided additional information on: (1) the survey design; (2) survey response rate; (3) excluded populations; (4) characteristics associated with response as judged by the authors of relevant sources; (5) survey adjustments for excluded or underrepresented populations; (6) supplementary or parallel mental health surveys of non-responders or excluded populations; or (7) additional analyses on the association between survey response and disorder prevalence. Where supplementary surveys or additional analyses were explicitly identified in the primary publication, an additional search was conducted using the same Google search and snowballing method to identify relevant publications.

Supplementary non-response surveys were included for data extraction if they collected data on mental health, including symptom measures or diagnosis history. Since resource limitations may restrict the number of additional surveys conducted over time, supplementary surveys of excluded populations conducted for both past and current iterations of the primary survey (up to a maximum of two) were included for data extraction so long as they collected information on mental health, including a diagnostic interview, symptom measures or diagnosis history. Non-response and supplementary surveys focused solely on substance use disorders, mental health treatment or self-harm, suicide attempts and suicidal ideation were not included.

Data extraction and synthesis

Survey information extracted from relevant sources included country, survey year, survey design, sample size, psychiatric disorders of interest, psychological assessment instruments and response rate. Information extracted on psychiatric disorders excluded indicators of self-harm; suicidal thoughts; suicide attempts; smoking; use of tobacco products; nicotine use, dependence or withdrawal; alcohol or drug use where this was not characterised as harmful, problematic or a substance use disorder; and other general health and well-being measures (e.g. quality of life). Next, data were extracted to describe populations that were identified as underrepresented or less likely to respond, as well as groups that were excluded from participating in the survey because of the sampling methodology or eligibility criteria.

Finally, information was extracted from the relevant literature on additional efforts undertaken to survey non-responders or excluded groups, or to investigate the impacts of response rate on prevalence estimates. This included data on the general design and methodology of the supplementary survey or analysis as well as the year, sample size, psychological assessment measures used, response rate and key findings.

Where relevant data were missing from existing literature or questions remained regarding the sampling methodology, exclusion criteria or supplementary surveys, up to three contributing authors of included sources were contacted for more information.

Following a preliminary review of the data, categories for frequently excluded groups were established through an iterative process, beginning with the categories identified in the source literature and grouping these based on similar characteristics and reasons for exclusion. This process facilitated comparisons between surveys. The data extraction and synthesis were conducted and reviewed by EW, IP and CP.

Results

Survey characteristics

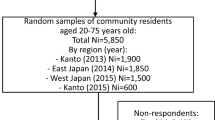

Twenty-two sources from the GBD Data Input Sources Tool described surveys that met our criteria. After accounting for sources that used the same survey, 16 individual surveys [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29] conducted in 14 countries were included for analysis (Figure 1). Table 1 provides an overview of the methods for each included survey. Fourteen surveys sampled adults only [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26], while 2 surveys also included children and adolescents under the age of 15 years [27,28,29]. Fifteen of the surveys were conducted in person [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29] and 2 was mailed to participants [21], who could mail back the completed survey or complete it online. Three surveys explicitly described attempts to account for the possible underrepresentation of specific groups in their sampling methodologies [11, 13, 20, 27, 29], while 14 applied post-stratification weighting to adjust for sampling bias and non-response and improve representativeness [11,12,13,14,15,16,17, 19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29]. All surveys included measures of anxiety and depressive disorders [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29], 4 included psychotic disorders [12, 14, 19, 20, 26], 2 included personality disorders [12, 14, 19], 2 included conduct or impulse control disorders [19, 22], 1 included autism spectrum disorders [12, 14] and 13 included substance use disorders [11,12,13,14,15,16, 18,19,20, 22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29]. All 13 surveys that included substance use disorders included measures of alcohol use disorders [11,12,13,14,15,16, 18,19,20, 22, 24,25,26,27,28,29], while 10 also collected information on other drug use disorders [11,12,13,14,15, 18, 19, 20, 22, 24, 27, 28, 29]. Most surveys were conducted by government agencies and/or academic collaboratives.

Identification of national mental health surveys [10]

Excluded populations

Details about inclusion and exclusion criteria were identified for all included surveys; however, the amount of information provided was highly variable. Based on available published data, we identified 13 populations or groups that were commonly excluded from national mental health surveys (Table 2). These populations are listed below in order from most to least commonly excluded:

-

Homeless people with no fixed address (14 of 16 surveys).

-

People in hospitals and health facilities (14 of 16 surveys.)

-

People residing in correctional facilities (14 of 16 surveys).

-

People in residential care facilities (12 of 16 surveys).

-

Military personnel on base or abroad (12 of 16 surveys).

-

Non-local language speakers (11 of 16 surveys).

-

People residing in temporary housing (11 of 16 surveys).

-

Short-term overseas visitors (11 of 16 surveys).

-

People living on islands, in remote areas or in specific territories (9 of 16 surveys).

-

People living in other non-private dwellings (e.g. migratory worker dormitories, detention facilities, monasteries, etc.) (8 of 16 surveys).

-

People living in educational institutions (7 of 16 surveys).

-

Non-residents (7 of 16 surveys).

-

People with a cognitive impairment (7 of 16 surveys).

Information was missing and could not be obtained on the inclusion or exclusion of some of these groups for ten of the surveys, two of which only had data available on the eligibility of one population (see Table 2).

It is worth noting that many surveys only sampled people living in private dwellings, and this often constituted the reason some groups were or may have been excluded. Furthermore, the location-based criteria were often only applicable to the time period in which the fieldwork was conducted and/or whether the individual had a fixed residential address [19, 30, 31]. For instance, a student with a fixed address outside of their educational institution would have been eligible for the 2014 survey in England [30] or the 2010–2011 survey in Poland [31] if they had returned home during the sampling period in that area.

Fewer than half of the surveys had literature that discussed the eligibility of people with a cognitive impairment [13, 20, 25, 29, 32, 33]. In two instances where authors were able to be contacted, it was suggested that while there was no formal cognitive assessment conducted as part of the sampling process, there would likely be a degree of self-selection or implicit exclusion where individuals were unable to understand and respond to the survey questions [34, 35]. In the case of the Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey (APMS) conducted in England in 2014, personal communication with the survey team stated that individuals with a cognitive impairment were likely to be excluded unless the impairment was mild [30]. As such, we considered that this exclusion criterion was applied on a case-by-case basis.

Response rate, underrepresented groups and non-responder characteristics

Survey response rates ranged from 36.3% [23] to 80% [27] (Table 1). Ten of the included surveys had sources that compared the characteristics of people in the survey sample to those of the general population [11, 13, 14, 16,17,18,19,20,21, 25, 26]. Analysis of these findings showed that males [14, 17, 19, 20, 25] and younger adult cohorts [14, 17, 19] were the most commonly underrepresented groups. Literature on four surveys also reported on factors associated with response rate [13, 16, 19, 24]. However, no common factors influencing response rate were identified between the surveys.

Supplementary surveys of excluded populations

Attempts to capture excluded populations through supplementary surveys were identified for four of the primary surveys included in our analysis (Table 3):

-

The 2007 NSMHWB in Australia

-

The Canadian Community Health Survey- Mental Health (CCHS-MH).

-

The APMS 2014 in England.

-

The 2014 NSDUH in the USA.

Supplementary survey findings from Australia showed that while the overall rate of moderate psychological distress in rural and remote areas was similar to that reported for the general household survey [42], distress scores indicating caseness were >10% more prevalent in very remote locations relative to other rural and remote regions [46]. Data from the supplementary surveys conducted in Canada showed that major depressive disorder, generalised anxiety disorder and panic disorder were more prevalent in Canadian military personnel than in members of the civilian population [47,48,49,50]. While there were no direct comparisons between the military surveys and the 2014 NSDUH findings in the USA, comparisons made to earlier survey results in the USA also indicated higher rates of mental disorders in active-duty soldiers [55, 56].

The supplementary survey of people in correctional facilities in England and Wales showed that significant neurotic symptoms and functional psychosis were far more common among prisoners than members of the general population [53]. While comparisons between surveys in the USA were limited by differences in the measures used, the results from the National Inmate Survey (NIS-3) also showed significantly higher rates of severe psychological distress among inmates when compared to the general population [58, 59].

The supplementary survey of homeless people conducted in Great Britain showed that the prevalence rates of common mental disorders, psychotic disorders, and alcohol and non-cannabinoid drug dependence were significantly higher in this group than the general population [52, 62]. In contrast, the supplementary survey of ethnic minority populations found that common mental disorders were more prevalent in people who were interviewed in English and would therefore not have been excluded from the general household survey [51].

Lastly, the supplementary survey of residents of institutions catering to people with mental illness in Great Britain showed a high proportion of people with severe disorders including schizophrenia, delusional disorder, schizoaffective disorder and affective psychoses, particularly in hospital settings [54]. Neurotic disorders, however, were more common in residential settings and comparisons to the general household survey data suggest that while people with these disorders do spend time in hospital, their length of stay in those facilities is likely to be relatively short in most cases [54].

Supplementary surveys of non-responders

The 2007 National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing (NSMHWB) in Australia and the Netherlands Mental Health Survey and Incidence Study (NEMESIS-2) attempted to contact non-responders for information on their mental health (Table 4). In both instances, an abridged version of the original survey was used, which allowed for some comparison between responders and non-responders [11, 13, 19].

The NSMHWB Non-response Follow-up Survey (NRFUS) found that psychological distress, as measured by the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10), was higher among non-responders than in the responding NSMHWB sample [13]. However, applying the NRFUS scores to the broader population of people who did not respond to the NSMHWB did not significantly increase the overall K10 score for the survey [13]. The NEMESIS-2 non-response survey found that compared to responders, non-responders were significantly more likely to have recent mood and anxiety problems as well as at least one impulse control symptom in childhood [19]. Despite the reduced survey content, participation rates for these follow-up surveys remained poor, with only 26.1% [19] to 40% [11, 13] of people who were contacted responding.

Another survey in Japan, the WMHJ2, analysed the association between response rate and mental disorder prevalence in different regions and conducted additional sampling of an area with a low response rate [18]. The findings showed no association between disorder prevalence and regional response rate; a lower disorder prevalence was reported for the area that was re-sampled when a higher response rate was achieved [18].

Discussion

Our review of national mental health surveys found that people not living in private dwellings in the community, especially those who are homeless, in health or correctional facilities, were commonly excluded from sampling, while males and young people were commonly underrepresented among survey respondents. Supplementary surveys of excluded populations and non-responders, where available, indicated higher prevalence of mental health problems in many of these groups. The common exclusion of key vulnerable groups and relatively high rates of non-response in these surveys have important implications for how results are used and interpreted.

The findings of this review show that most national mental health surveys recently conducted in high-income countries employ a similar approach and therefore have similar limitations concerning excluded populations and non-responders. This is not entirely surprising as six of the surveys included for review were either part of the WMH Survey Initiative or rooted in a previous WMH survey conducted in that country [11, 13, 18, 22,23,24,25,26]. Furthermore, given the recognition and prominence of the WMH Initiative, other independent surveys may have adopted similar sampling methodologies.

Four surveys included for review explicitly attempted to quantify the proportion of the population that would be excluded according to their methodology, with estimates ranging between 1% and 3.5% [15, 20, 25, 27, 29]. However, since countries may differ considerably with respect to the size of some excluded groups (e.g. military personnel, non-local language speakers), these figures may not be more widely representative. While the exclusion of such a small proportion of the total population may have had little to no impact on the overall survey results, as was sometimes articulated in the literature [19], excluded groups may have accounted for a far larger proportion of people in a particular subpopulation with specific risk factors and service needs (e.g. minority group, age cohort, or clinical severity group) [11, 63, 64]. In that instance, a difference in disease prevalence between included and excluded individuals could significantly affect the accuracy of disorder and service need estimates generated for that subpopulation. It may also impact the estimates of disease burden, particularly where individuals with more severe disorders are undersampled.

For example, data from 12 high-income OECD countries in 2019 showed that the proportion of people 80 years of age or older receiving care in long-term (i.e. residential) facilities (excluding hospitals) ranged between 10-19% [65]. Therefore, while this group may represent a relatively small proportion of a country’s total population, they would account for a far larger proportion of the elderly population. Research also suggests that mental disorders are more common among people residing in residential care relative to their community-dwelling counterparts [66, 67], yet only one of the surveys that met our inclusion criteria sampled this population [27, 29]. The exclusion of people in residential care from surveys may therefore result in an underestimate of both the disorder prevalence for this age group and the resources required to meet the needs of those living in these settings. As the populations in high-income countries continue to age, the impact of this group’s exclusion is likely to become even more profound [68].

Data from the supplementary surveys indicated that many of the other groups commonly excluded from population-based mental health surveys are also especially vulnerable to psychological distress and mental illness, including prisoner populations [53, 58, 59], military personnel [48,49,50, 57], homeless people [52, 62], people in hospitals and other health facilities [54], and people living in very remote areas [44,45,46]. It is particularly important to note the small number of surveys that included psychotic and personality disorders as well as the overrepresentation of individuals with a severe disorder among homeless populations [52, 62], prisoner populations [53] and people in hospitals and health facilities [54]. Individuals with severe mental disorders have high service needs, with estimates from England indicating that hospital admissions for these disorders account for 7% of total bed days for all health conditions [69, 70]. It is therefore imperative that service planning adequately account for the needs of these groups. One approach to gaining a better understanding of the size, distribution and needs of these populations is by conducting surveys through existing mental health services, like the Survey of High Impact Psychosis in Australia [71] and its predecessor the Study on Low Prevalence Disorders [72]. In countries with patient registers like Denmark, data on these populations are instead typically derived from admissions data [73, 74], however both methodologies are limited in that they rely on individuals with severe disorders being in contact with health services.

The lack of clear criteria around the inclusion or exclusion of people with cognitive impairment was another important finding of this review. Research has shown that individuals with a cognitive impairment or intellectual disability have a higher prevalence of mental disorders than those without, and have more complex service needs as a result of their comorbid conditions [75, 76]. As such, ambiguity regarding the inclusion of these individuals in national mental health surveys may complicate attempts to interpret and use survey data with respect to understanding and planning for mental health services overall and specifically for this population.

Survey results may be skewed if non-responders have a different mental health profile. Recent research shows that the response rates for health surveys in high-income countries have generally declined over time [77,78,79] and this trend was noted where previous iterations of the mental health surveys included in this review could be identified [14, 15, 19, 80,81,82,83,84]. Few studies attempted to capture non-responders or people in excluded groups through supplementary surveys or additional survey rounds, thereby limiting the generalisability of their results. In some cases, supplementary surveys also used different mental health measures, thus preventing the direct comparison or integration of results to those of the broader population surveys.

Similar to previous findings, supplementary analyses of non-response did not show a consistent relationship between survey response and mental health status. The first NEMESIS survey conducted in 1996 found that non-responders who agreed to complete the 12-item General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12) had slightly better average mental health scores when compared to those who participated in the full diagnostic interview [80]. On the other hand, high levels of mental distress were associated with increased rates of attrition from the Nord-Trøndelag Health Study (HUNT) in Norway [85] and previous psychiatric diagnoses were tied to lower rates of participation in the population-based PART (Psykisk hälsa, Arbete och RelaTioner) study on mental health in Sweden [86]. Finally, while considerable evidence has linked heavy alcohol consumption, alcohol-related problems and financial support or hospital treatment for substance use disorders to lower rates of survey response [85,86,87,89,90], the opposite relationship has also been found [91,92,93,94].

Strategies adopted for the purposes of improving response rates included financial incentives, i.e. money or vouchers (Response Rate (RR): 57.3-65.1%) [12, 19, 20, 25], pre-survey notification (RR: 43.4-80%) [12, 15, 18, 19, 20, 24, 25, 27, 28], follow-up contact attempts (RR: 57.3-80%) [13, 15, 19,20,21, 25,26,27] and interviewing or contacting people face-to-face (60- 65.1%) [13, 19]. Interestingly, the survey that was mailed to potential participants had one of the lowest response rates (44.3%) [21] of the surveys reviewed, while the survey with the highest response rate (80%) had one of the shortest mental health questionnaires [27, 29], supporting previous findings that shorter questionnaires improve participation [95].

The underrepresentation of males and young people in our findings has also been reported in other health and health-related surveys [96,97,98,99,100]. One of the surveys included in our review oversampled younger people to ensure adequate representation [11, 13]. No surveys specifically adjusted their sampling methodology to account for sex or gender; however, nearly all surveys applied sampling weights to adjust for lower response rates and reflect the demographics of the general population [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29]. It is possible that there may also be other populations that are underrepresented in survey findings but that were not specifically mentioned in the related literature, such as shift workers, fly in–fly out workers and long-haul transport drivers, all of whom have been found to be at elevated risk of poor mental health [101,102,103,104]. Other more specific issues with survey sampling methodologies, such as those described by Kalton et al.[105], were outside the scope of this review.

Planners and policymakers should be aware of the limitations of the mental health surveys that they use to understand mental health service needs and resource requirements. Ideally, efforts to sample non-responders and previously excluded populations would be included in all national mental health survey designs, or in complementary studies that use a standardised methodology to allow direct comparisons. However, given the significant additional resources required, sampling these populations may not always be feasible. In such instances, end users of survey results could consider other available data on the level of need within excluded populations to adjust estimates where appropriate. Adjustments of this kind were recently made to the prevalence estimates informing the mental health service demand and resource requirement modelling for adequate care in Australia’s NMHSPF (more information available in the NMHSPF V4.1 Technical Appendices [4]). Behan and Kennelly [106] used a similar approach to incorporate homeless and prison populations into their estimates for the cost of schizophrenia in Ireland. Given the increasing rates of non-response, groups conducting future surveys may also want to give greater consideration to factors that could influence participation, such as survey length and method of delivery, in their survey design [95].

Strengths and limitations

The lack of information available on which groups were included and excluded from many of the surveys was a key finding and limitation of this review. It suggests that more consistent reporting of these criteria in survey methodologies would be highly beneficial to improving our understanding of prevalence rates and facilitating comparisons between surveys. Another important limitation of this review was that the search for supplementary surveys of non-responders and excluded populations was restricted to those explicitly referred to in the primary survey literature. As a result, other potentially relevant surveys would not have been identified. For example, the First Nations Regional Health Survey conducted in Canada between 2008 and 2010 sampled First Nations communities that would have been excluded from the national mental health survey, but was not identified through our search criteria [107]. Unfortunately, a broader search of supplementary surveys was not feasible given the large number of excluded groups that were identified. Finally, as the review was limited to surveys conducted in high-income OECD countries, the findings may not be applicable to other settings.

Conclusion

This study showed that there are key populations that are often excluded from national mental health surveys in high-income countries (e.g. persons who are homeless, in hospitals or health facilities, or correctional institutions). The exclusion of these populations, and the few attempts to follow-up survey non-responders, may limit the generalisability of survey findings and result in underestimates of need for care. Collectively, our findings suggest the need for more inclusive sampling methods, or targeted population surveys, to strengthen the accuracy of prevalence estimates drawn from these surveys to inform policy and service planning decisions. If there are resource restrictions that limit the feasibility of these options, consideration should be given to whether prevalence estimates may be adjusted to account for any exclusions. Additionally, clear reporting on who is included and/or excluded in survey sampling procedures may ensure greater accuracy in the interpretation of survey findings.

Data availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

References

Kessler RC, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso J, Chatterji S, Lee S, Ustün TB (2009) The WHO world mental health (WMH) surveys. Psychiatrie (Stuttg) 6(1):5–9

Weinberg L, Whiteford H, de Almeida JC, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Levinson D, O’Neill S, Kovess-Masfety V (2012) Translation of the world mental health survey data to policies: an exploratory study of Stakeholders’ perceptions of how epidemiologic data can be utilized for policy in the field of mental health. Public Health Rev 34(2):4. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03391672

Chisholm D, Heslin M, Docrat S, Nanda S, Shidhaye R, Upadhaya N, Jordans M, Abdulmalik J, Olayiwola S, Gureje O, Kizza D, Mugisha J, Kigozi F, Hanlon C, Adugna M, Sanders R, Pretorius C, Thornicroft G, Lund C (2017) Scaling-up services for psychosis, depression and epilepsy in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia: development and application of a mental health systems planning tool (OneHealth). Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci 26(3):234–244. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796016000408

Diminic S, Page I, Gossip K, Comben C, Wright E, Pagliaro C, John J (2022) Technical Appendices for the Introduction to the National Mental Health Service Planning Framework – Commissioned by the Australian Government Department of Health. Version AUS V4.1. The University of Queensland, Brisbane

Wright E, Leitch E, Fjeldsoe K, Diminic S, Gossip K, Hudson P, Whiteford H (2021) Using the national mental health service planning framework to support an integrated approach to regional mental health planning in Queensland. Australia Aust J Primary Health 27(2):109–115

Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (2022) Global Burden of Disease Study 2019 (GBD 2019) Data Input Sources Tool. University of Washington. https://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-2019/data-input-sources#:~:text=The%20Global%20Burden%20of%20Disease,sources%20and%20retrieve%20relevant%20metadata. Accessed 1 July 2021

Collaborators GMD (2022) Global, regional, and national burden of 12 mental disorders in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global burden of disease study 2019. The Lancet Psychiatry 9(2):137–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00395-3

Sayers A (2007) Tips and tricks in performing a systematic review. Br J Gen Pract 57(542):759

scite_. (2022). https://scite.ai/. Accessed 9 June 2021

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman D (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 6(7):e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed1000097

Slade T, Johnston A, Oakley Browne M, Andrews G, Whiteford H (2009) 2007 National survey of mental health and wellbeing: methods and key findings. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 43:594–605. https://doi.org/10.1080/00048670902970882

McManus S, Bebbington P, Jenkins R, Brugha T (eds) (2016) Mental health and wellbeing in England: Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey 2014. NHS Digital, Leeds

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2009) 2007 National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing: users’ guide. Australian Bureau of Statistics, Canberra

McManus S, Bebbington PE, Jenkins R, Morgan Z, Brown L, Collinson D, Brugha T (2020) Data resource profile: adult psychiatric morbidity survey (APMS). Int J Epidemiol 49(2):361–362e. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyz224

Statistics Canada (2013) Canadian Community Health Survey - Mental Health (CCHS). Statistics Canada. https://www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb/p2SV.pl?Function=getSurvey&Id=119789. Accessed 29 April 2022

Skapinakis P, Bellos S, Koupidis S, Grammatikopoulos I, Theodorakis PN, Mavreas V (2013) Prevalence and sociodemographic associations of common mental disorders in a nationally representative sample of the general population of Greece. BMC Psychiatry 13:163. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244x-13-163

Barry M, Van Lente E, Molcho M, Morgan K, McGee H, Conroy R, Watson D, Shelley E, Perry I (2009) SLAN 2007: Survey of lifestyle. Attitudes and nutrition in Ireland mental health and social well-being report, Department of Health and Children, Dublin

Ishikawa H, Tachimori H, Takeshima T, Umeda M, Miyamoto K, Shimoda H, Baba T, Kawakami N (2018) Prevalence, treatment, and the correlates of common mental disorders in the mid 2010’s in Japan: the results of the world mental health Japan 2nd survey. J Affect Disord 241:554–562

de Graaf R, Ten Have M, van Dorsselaer S (2010) The Netherlands Mental Health Survey and Incidence Study-2 (NEMESIS-2): design and methods. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 19(3):125–141. https://doi.org/10.1002/mpr.317

Grant BF, Chu A, Sigman R, Amsbary M, Kali J, Sugawara Y, Jiao R, Ren W, Goldstein R (2014) Source and accuracy statement: national epidemiologic Survey on alcohol and related conditions-III (NESARC-III). National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, Rockville, MD

Johansson R, Carlbring P, Heedman Å, Paxling B, Andersson G (2013) Depression, anxiety and their comorbidity in the Swedish general population: point prevalence and the effect on health-related quality of life. PeerJ 1:e98. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.98

Bunting B, Murphy S, O’Neill S, Ferry F (2013) Prevalence and treatment of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the Northern Ireland study of health and stress. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 48(1):81–93. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-012-0518-5

Song TJ, Cho SJ, Kim WJ, Yang KI, Yun CH, Chu MK (2017) Anxiety and depression in probable migraine: A population-based study. Cephalalgia 37(9):845–854. https://doi.org/10.1177/0333102416653235

Kiejna A, Adamowski T, Piotrowski P, Moskalewicz J, Wojtyniak B, Świątkiewicz G, Stokwiszewski J, Kantorska-Janiec M, Zagdańska M, Kessler R (2015) “Epidemiology of mental disorders and access to mental health care EZOP – Poland” - research methodology. Psychiatr Pol 49(1):5–13. https://doi.org/10.1240/pp/30810

Xavier M, Baptista H, Mendes JM, Magalhães P, Caldas-de-Almeida JM (2013) Implementing the world mental health survey initiative in Portugal - rationale, design and fieldwork procedures. Int J Ment Health Syst 7(1):19–19. https://doi.org/10.1186/1752-4458-7-19

Cho MJ, Seong SJ, Park JE, Chung IW, Lee YM, Bae A, Ahn JH, Lee DW, Bae JN, Cho SJ, Park JI, Son J, Chang SM, Hahm BJ, Lee JY, Sohn JH, Kim JS, Hong JP (2015) Prevalence and correlates of DSM-IV mental disorders in South Korean adults: the Korean epidemiologic catchment area study 2011. Psychiatry Investig 12(2):164–170. https://doi.org/10.4306/pi.2015.12.2.164

Ministry of Health (2017) Methodology Report 2016/17: New Zealand Health Survey. Ministry of Health, Wellington

Center for Behavioural Health Statistics and Quality (2015) Behavioural health trends in the United States: Results from the 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. (HHS Publication No. SMA 15–4927, NSDUH Series H-50). Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Rockville, MD

Ministry of Health (2017) Content Guide 2016/17: New Zealand Health Survey. Ministry of Health, Wellington

McManus S (sally.mcmanus@natcen.ac.uk). Mental Health Survey Queries. Email to: Wright E (e.wright1@uq.edu.au). 9 September 2021.

Kiejna A (andrzej.kiejna46@gmail.com). EZOP survey query. Email to: Wright E (e.wright1@uq.edu.au). 10 December 2021.

Bunting BP, Ferry FR, Murphy SD, O’Neill SM, Bolton D (2013) Trauma associated with civil conflict and posttraumatic stress disorder: evidence from the Northern Ireland study of health and stress. J Trauma Stress 26(1):134–141. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.21766

Bujalski M, Moskalewicz J, Stokwiszewski J (2021) Occupational position and alcohol use disorders in Poland. Int J Occup Med Environ Health 34(5):591–602. https://doi.org/10.13075/ijomeh.1896.01729

Patten S (patten@ucalgary.ca). Community mental health survey questions. Email to: Wright E (e.wright1@uq.edu.au). 1 November 2021 - 5 May 2022.

The CBHSQ Request Team (cbhsqrequest@samhsa.hhs.gov). Query about the 2014 NSDUH. Email to: Wright E (e.wright1@uq.edu.au). 25 March 2022.

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2008) National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing: Summary of Results methodology. https://www.abs.gov.au/methodologies/national-survey-mental-health-and-wellbeing-summary-results-methodology/2007. Accessed 19 April 2022

McManus S, Meltzer H, Brugha T, Bebbington P, Jenkins R, (2009) Adult psychiatric morbidity in England, 2007: Results of a household survey. https://doi.org/10.13140/2.1.1563.5205

Hisateru T (tachi@ncnp.go.jp). Query about the WMHJ2. Email to: Wright E (e.wright1@uq.edu.au). 9–28 April 2022.

Umeda M, Shimoda H, Miyamoto K, Ishikawa H, Tachimori H, Takeshima T, Kawakami N (2021) Comorbidity and sociodemographic characteristics of adult autism spectrum disorder and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: epidemiological investigation in the world mental health Japan 2nd survey. Internat J Develop Disabilities 67(1):58–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/20473869.2019.1576409

Xavier M (migxavier@gmail.com). Query about the Portuguese National Mental Health Study. Email to: Wright E (e.wright1@uq.edu.au). 19 April 2022.

Hasin DS, Sarvet AL, Meyers JL, Saha TD, Ruan WJ, Stohl M, Grant BF (2018) Epidemiology of adult DSM-5 major depressive disorder and its specifiers in the United States. JAMA Psychiat 75(4):336–346. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.4602

Perkins D, Fuller J, Kelly BJ, Lewin TJ, Fitzgerald M, Coleman C, Inder KJ, Allan J, Arya D, Roberts R, Buss R (2013) Factors associated with reported service use for mental health problems by residents of rural and remote communities: cross-sectional findings from a baseline survey. BMC Health Serv Res 13(1):157. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-13-157

Inder KJ, Handley TE, Fitzgerald M, Lewin TJ, Coleman C, Perkins D, Kelly BJ (2012) Individual and district-level predictors of alcohol use: cross sectional findings from a rural mental health survey in Australia. BMC Public Health 12:586–586. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-586

Butterworth P, Handley TE, Lewin TJ, Reddy P, Kelly BJ (2014) Psychological distress in rural Australia: regional variation and the role of family functioning and social support. J Public Health 22(6):481–488. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-014-0640-9

Kelly BJ, Lewin TJ, Stain HJ, Coleman C, Fitzgerald M, Perkins D, Carr VJ, Fragar L, Fuller J, Lyle D, Beard JR (2011) Determinants of mental health and well-being within rural and remote communities. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 46(12):1331–1342. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-010-0305-0

Kelly BJ, Stain HJ, Coleman C, Perkins D, Fragar L, Fuller J, Lewin TJ, Lyle D, Carr VJ, Wilson JM, Beard JR (2010) Mental health and well-being within rural communities: the Australian rural mental health study. Aust J Rural Health 18(1):16–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1584.2009.01118.x

Zamorski MA, Bennett RE, Boulos D, Garber BG, Jetly R, Sareen J (2016) The 2013 Canadian Forces Mental Health Survey: Background and Methods. Canadian J Psychiatry 61(1 Suppl):10s–25s. https://doi.org/10.1177/0706743716632731

Fikretoglu D, Liu A, Zamorski MA, Rusu C, Jetly R (2018) Do investments in mental health systems result in greater use of mental health services? national trends in mental health service use (MHSU) in the Canadian military and comparable Canadian civilians, 2002–2013. Canadian J psychiatry Revue canadienne de psychiatrie 63(9):602–609. https://doi.org/10.1177/0706743718760291

Taillieu TL, Afifi TO, Turner S, Cheung K, Fortier J, Zamorski M, Sareen J (2018) Risk factors, clinical presentations, and functional impairments for generalized anxiety disorder in military personnel and the general population in Canada. Canadian J Psychiatry 63(9):610–619. https://doi.org/10.1177/0706743717752878

Statistics Canada (2014) ARCHIVED - The CF 2002 Supplement of the Statistics Canada Canadian Community Health Survey. Government of Canada. https://www.canada.ca/en/department-national-defence/corporate/reports-publications/health/cf-2002-supplement-of-the-statistics-can-canadian-community-health-survey.html. Accessed 19 April 2022

Weich S, Nazroo J, Sproston K, McManus S, Blanchard M, Erens B, Karlsen S, King M, Lloyd K, Stansfeld S, Tyrer P (2004) Common mental disorders and ethnicity in England: the EMPIRIC study. Psychol Med 34(8):1543–1551. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291704002715

Gill B, Meltzer H, Hinds K (2003) The prevalence of psychiatric morbidity among homeless adults. Int Rev Psychiatry 15(1–2):134–140. https://doi.org/10.1080/0954026021000046056

O’Brien M, Mortimer L, Singleton N, Meltzer H (2003) Psychiatric morbidity among prisoners in England and wales. Int Rev Psychiatry 15:153–157. https://doi.org/10.1080/0954026021000046100

Meltzer H, Gill B, Hinds K, Petticrew M (2003) The prevalence of psychiatric morbidity among adults living in institutions. Int Rev Psychiatry 15(1–2):129–133. https://doi.org/10.1080/0954026021000046047

Barlas F, Higgins W, Pflieger J, Diecker K (2013) 2011 Health Related Behaviors Survey of Active Duty Military Personnel ICF international, Fairfax

Bray RM, Pemberton MR, Hourani LL, Witt M, Olmsted KLR, Brown JM, Weimer B, Lane ME, Marsden ME, Scheffler S, Vandermaas-Peeler R, Aspinwall KR, Anderson E, Spagnola K, Close K, Gratton JL, Calvin S, Bradshaw M (2009) 2008 Department of Defense Survey of Health Related Behaviors Among Active Duty Military Personnel

Rosellini AJ, Heeringa SG, Stein MB, Ursano RJ, Chiu WT, Colpe LJ, Fullerton CS, Gilman SE, Hwang I, Naifeh JA, Nock MK, Petukhova M, Sampson NA, Schoenbaum M, Zaslavsky AM, Kessler RC (2015) Lifetime prevalence of DSM-IV mental disorders among new soldiers in the U.S army: results from the army study to assess risk and resilience in servicemembers (army STARRS). Depression Anxiety 32(1):13–24. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22316

Bronson J, Berzofsky M (2017) Indicators of Mental Health Problems Reported by Prisoners and Jail Inmates, 2011–12. Bureau of Justice Statistics,

Beck AJ, Berzofsky M, Caspar R, Krebs C (2013) Sexual victimization in prisons and jails reported by inmates, 2011–12: National Inmate Survey, 2011–12 (NCJ 241399). US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics, Washington, DC

Reingle Gonzalez JM, Connell NM (2014) Mental health of prisoners: identifying barriers to mental health treatment and medication continuity. Am J Public Health 104(12):2328–2333. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2014.302043

James DJ, Glaze LE (2006) Mental Health Problems of Prison and Jail Inmates. Bureau of Justice Statistics, Washington, DC

Smith J (2005) Housing, homelessness, and mental health in great Britain. Int J Ment Health 34(2):22–46

Bilevicius E, Sommer JL, Keough MT, El-Gabalawy R (2020) An examination of comorbid generalized anxiety disorder and chronic pain on substance misuse in a Canadian population-based survey. Canadian J Psychiatry 65(6):418–425. https://doi.org/10.1177/0706743719895340

Palay J, Taillieu TL, Afifi TO, Turner S, Bolton JM, Enns MW, Smith M, Lesage A, Bakal JA, Rush B, Adair CE, Vigod SN, Clelland S, Rittenbach K, Kurdyak P, Sareen J (2019) Prevalence of mental disorders and suicidality in Canadian provinces. The Canadian J Psychiatry 64(11):761–769. https://doi.org/10.1177/0706743719878987

OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) (2021) Long-Term Care Resources and Utilisation: Long-term care recipients. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. https://stats.oecd.org/. Accessed 5 May 2022

Amare AT, Caughey GE, Whitehead CH, Lang CE, Bray SCE, Corlis M, Visvanathan R, Wesselingh SL, Inacio MC (2020) The prevalence, trends and determinants of mental health disorders in older Australians living in permanent residential aged care: implications for policy and quality of aged care services. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 54:1200–1211. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867420945367

Creighton AS, Davison TE, Kissane DW (2016) The prevalence of anxiety among older adults in nursing homes and other residential aged care facilities: a systematic review. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 31(6):555–566. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.4378

World Health Organisation (2015) World report on ageing and health. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland

Jacobs R, Gutacker N, Mason A, Goddard M, Gravelle H, Kendrick T, Gilbody S (2015) Determinants of hospital length of stay for people with serious mental illness in England and implications for payment systems: a regression analysis. BMC Health Serv Res 15(1):439. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-015-1107-6

Hospital Episode Statistics, Admitted Patient Care, England - 2013–14 (2015). NHS Digital,

Morgan VA, Waterreus A, Jablensky A, Mackinnon A, McGrath JJ, Carr V, Bush R, Castle D, Cohen M, Harvey C, Galletly C, Stain HJ, Neil AL, McGorry P, Hocking B, Shah S, Saw S (2012) People living with psychotic illness in 2010: the second Australian national survey of psychosis. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 46(8):735–752. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867412449877

Jablensky A, McGrath J, Herrman H, Castle D, Gureje O, Evans M, Carr V, Morgan V, Korten A, Harvey C (2000) Psychotic disorders in urban areas: an overview of the study on low prevalence disorders. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 34(2):221–236. https://doi.org/10.1080/j.1440-1614.2000.00728.x

Gissler M, Laursen TM, Ösby U, Nordentoft M, Wahlbeck K (2013) Patterns in mortality among people with severe mental disorders across birth cohorts: a register-based study of Denmark and Finland in 1982–2006. BMC Public Health 13(1):834. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-834

Kühl JOG, Laursen TM, Thorup A, Nordentoft M (2016) The incidence of schizophrenia and schizophrenia spectrum disorders in Denmark in the period 2000–2012. Register-Based Study Schizophrenia Res 176(2):533–539. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2016.06.023

White P, Chant D, Edwards N, Townsend C, Waghorn G (2005) Prevalence of intellectual disability and comorbid mental illness in an Australian community sample. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 39(5):395–400. https://doi.org/10.1080/j.1440-1614.2005.01587.x

Buckles J, Luckasson R, Keefe E (2013) A systematic review of the prevalence of psychiatric disorders in adults with intellectual disability, 2003–2010. J Mental Health Res Intellectual Disabilities 6(3):181–207. https://doi.org/10.1080/19315864.2011.651682

Mölenberg FJM, de Vries C, Burdorf A, van Lenthe FJ (2021) A framework for exploring non-response patterns over time in health surveys. BMC Med Res Methodol 21(1):37. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-021-01221-0

Mindell JS, Giampaoli S, Goesswald A, Kamtsiuris P, Mann C, Männistö S, Morgan K, Shelton NJ, Verschuren WM, Tolonen H (2015) Sample selection, recruitment and participation rates in health examination surveys in Europe–experience from seven national surveys. BMC Med Res Methodol 15:78. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-015-0072-4

Galea S, Tracy M (2007) Participation rates in epidemiologic studies. Ann Epidemiol 17(9):643–653. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annepidem.2007.03.013

Bijl RV, van Zessen G, Ravelli A, de Rijk C, Langendoen Y (1998) The Netherlands mental health survey and incidence study (NEMESIS): objectives and design. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 33(12):581–586. https://doi.org/10.1007/s001270050097

Parslow RA, Lewis V, Marsh G (2011) The general practitioner’s role in providing mental health services to Australians, 1997 and 2007: findings from the national surveys of mental health and wellbeing. Med J Aust 195(4):205–209. https://doi.org/10.5694/j.1326-5377.2011.tb03282.x

Gravel R, Béland Y (2005) The Canadian community health survey: mental health and well-being. Canadian J Psychiatry 50(10):573–579. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674370505001002

Nishi D, Ishikawa H, Kawakami N (2019) Prevalence of mental disorders and mental health service use in Japan. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 73(8):458–465. https://doi.org/10.1111/pcn.12894

Park JE, Sohn JH, Sj S, Cho MJ (2015) Prevalence of sexual dysfunction and associations with psychiatric disorders AMONG women aged 50 and older. J Womens Health 24(6):515–523. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2014.5151

Torvik FA, Rognmo K, Tambs K (2012) Alcohol use and mental distress as predictors of non-response in a general population health survey: the HUNT study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 47(5):805–816. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-011-0387-3

Bergman P, Ahlberg G, Forsell Y, Lundberg I (2010) Non-participation in the second wave of the PART study on mental disorder and its effects on risk estimates. Int J Soc Psychiatry 56(2):119–132. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764008098838

Wild TC, Cunningham J, Adlaf E (2001) Nonresponse in a follow-up to a representative telephone survey of adult drinkers. J Stud Alcohol Drugs 62(2):257–261. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsa.2001.62.257

Zhao J, Stockwell T, Macdonald S (2009) Non-response bias in alcohol and drug population surveys. Drug Alcohol Rev 28(6):648–657. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1465-3362.2009.00077.x

Knudsen AK, Hotopf M, Skogen JC, Overland S, Mykletun A (2010) The health status of nonparticipants in a population-based health study: the Hordaland health study. Am J Epidemiol 172(11):1306–1314. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwq257

Lundberg I, Damström Thakker K, Hällström T, Forsell Y (2005) Determinants of non-participation, and the effects of non-participation on potential cause-effect relationships, in the PART study on mental disorders. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 40(6):475–483. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-005-0911-4

Lahaut VMHCJ, Jansen HAM, van de Mheen D, Garretsen HFL (2002) NON-response bias in a sample survey on alcohol consumption. Alcohol Alcohol 37(3):256–260. https://doi.org/10.1093/alcalc/37.3.256

Dawson DA, Goldstein RB, Pickering RP, Grant BF (2014) Nonresponse bias in survey estimates of alcohol consumption and its association with harm. J Stud Alcohol Drugs 75(4):695–703. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsad.2014.75.695

Cranford JA, McCabe SE, Boyd CJ, Slayden J, Reed MB, Ketchie JM, Lange JE, Scott MS (2008) Reasons for nonresponse in a web-based survey of alcohol involvement among first-year college students. Addict Behav 33(1):206–210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.07.008

Hill A, Roberts J, Ewings P, Gunnell D (1997) Non-response bias in a lifestyle survey. J Public Health 19(2):203–207. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.pubmed.a024610

Edwards P, Roberts I, Clarke M, DiGuiseppi C, Pratap S, Wentz R, Kwan I, Cooper R (2007) Methods to increase response rates to postal questionnaires. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.MR000008.pub3

Holmen J, Midthjell K, Krüger Ø, Langhammer A, Holmen T, Bratberg G, Vatten L, Lund-Larsen P (2002) The NordTrøndelag Health Study 1995–97 (HUNT 2): Objectives, contents, methods and participation. Norsk Epidemiologi 13

Remington PL, Smith MY, Williamson DF, Anda RF, Gentry EM, Hogelin GC (1988) Design, characteristics, and usefulness of state-based behavioral risk factor surveillance: 1981–87. Public Health Rep 103(4):366–375

Vernay M, Malon A, Oleko A, Salanave B, Roudier C, Szego E, Deschamps V, Hercberg S, Castetbon K (2009) Association of socioeconomic status with overall overweight and central obesity in men and women: the French nutrition and health survey 2006. BMC Public Health 9(1):215. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-9-215

Pohjola V, Puolakka A, Kunttu K, Virtanen JI (2020) Association between dental fear, physical activity and physical and mental well-being among Finnish university students. Acta Odontol Scand 78(1):45–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/00016357.2019.1649457

Korkeila K, Suominen S, Ahvenainen J, Ojanlatva A, Rautava P, Helenius H, Koskenvuo M (2001) Non-response and related factors in a nation-wide health survey. Eur J Epidemiol 17(11):991–999. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1020016922473

Torquati L, Mielke GI, Brown WJ, Burton NW, Kolbe-Alexander TL (2019) Shift work and poor mental health: a meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Am J Public Health 109(11):e13–e20. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2019.305278

Bowers J, Lo J, Miller P, Mawren D, Jones B (2018) Psychological distress in remote mining and construction workers in Australia. Med J Aust 208(9):391–397. https://doi.org/10.5694/mja17.00950

da Silva-Júnior FP, de Pinho RSN, de Mello MT, de Bruin VMS, de Bruin PFC (2008) Risk factors for depression in truck drivers. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 44(2):125–129. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-008-0412-3

Crizzle AM, McLean M, Malkin J (2020) Risk factors for depressive symptoms in long-haul truck drivers. Inter J Environmental Res Public Health. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17113764

Kalton G, Kali J, Sigman R (2014) Handling frame problems when address-based sampling is used for in-person household surveys. J Survey Statistics Methodology 2(3):283–304. https://doi.org/10.1093/jssam/smu013

Behan C, Kennelly B, Callaghan E (2008) The economic cost of schizophrenia in Ireland: a cost of illness study. Irish J Psycholo Med 25:80–87. https://doi.org/10.1017/S079096670001106X

First Nations Information Governance Centre (FNIGC) (2012) First Nations Regional Health Survey (RHS) 2008/10: National report on adults, youth and children living in First Nations communities. FNIGC, Ottawa

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank several individuals who provided additional information on the surveys reviewed including Sally McManus, Prof. Tachimori Hisateru, Prof. Miguel Xavier, Prof. Scott Patten, Prof. Andrzej Kiejna and SAMHSA's Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality (CBHSQ) Request Team.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions. No funding was received for conducting this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

EW, IP, CP and SD contributed to the study conception and design. EW conducted the literature search, and EW, IP and CS reviewed the relevant literature. All authors contributed to writing the manuscript, and all reviewed, commented and edited previous versions of the manuscript before approving the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wright, E., Pagliaro, C., Page, I.S. et al. A review of excluded groups and non-response in population-based mental health surveys from high-income countries. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 58, 1265–1292 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-023-02488-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-023-02488-y