Abstract

Purpose

The health correlates of polygenic risk (PRS-SCZ) and exposome (ES-SCZ) scores for schizophrenia may vary depending on age and sex. We aimed to examine age- and sex-specific associations of PRS-SCZ and ES-SCZ with self-reported health in the general population.

Methods

Participants were from the population-based Netherlands Mental Health Survey and Incidence Study–2 (NEMESIS-2). Mental and physical health were measured with the 36-item Short Form Survey 4 times between 2007 and 2018. The PRS-SCZ and ES-SCZ were respectively calculated from common genetic variants and exposures (cannabis use, winter birth, hearing impairment, and five childhood adversity categories). Moderation by age and sex was examined in linear mixed models.

Results

For PRS-SCZ and ES-SCZ analyses, we included 3099 and 6264 participants, respectively (age range 18–65 years; 55.7–56.1% female). Age and sex did not interact with PRS-SCZ. Age moderated the association between ES-SCZ and mental (interaction: p = 0.02) and physical health (p = 0.0007): at age 18, + 1.00 of ES-SCZ was associated with − 0.10 of mental health and − 0.08 of physical health, whereas at age 65, it was associated with − 0.21 and − 0.23, respectively (all units in standard deviations). Sex moderated the association between ES-SCZ and physical health (p < .0001): + 1.00 of ES-SCZ was associated with − 0.19 of physical health among female and − 0.11 among male individuals.

Conclusion

There were larger associations between higher ES-SCZ and poorer health among female and older individuals. Accounting for these interactions may increase ES-SCZ precision and help uncover populational determinants of environmental influences on health.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The polygenic risk score (PRS-SCZ) and exposome score for schizophrenia (ES-SCZ) are indices of liability to schizophrenia. The PRS-SCZ captures cumulative effects of common genetic variants on the risk for schizophrenia [1, 2], while the ES-SCZ accounts for a range of schizophrenia-associated exposures such as cannabis use, winter birth, hearing impairment, and childhood adversity [3, 4]. To date, the PRS-SCZ and ES-SCZ are among the most robust and validated polygenic and exposome scores for mental disorders. Although these risk indices were developed to study the populational liability to schizophrenia, both scores are further associated with other relevant health conditions: in the general population, in addition to schizophrenia spectrum disorders [5, 6], they are associated with common mental disorders and a range of physical health outcomes [5,6,7,8]. The utility of PRS-SCZ and ES-SCZ thus extends to studying shared pathways of risk between schizophrenia and other health outcomes.

However, the health correlates of PRS-SCZ and ES-SCZ may vary as a function of age and sex [9,10,11]. For example, in non-clinical samples, PRS-SCZ seems to be more strongly related to cognition during late life [12], and its associations with cognitive task performance and schizotypy may be male-specific [13, 14]. Age- and sex-specific associations have not been examined with ES-SCZ specifically, but the count of schizophrenia-associated exposures is associated with earlier age at onset of psychosis [15, 16], and cumulative exposure to childhood adversity is associated with greater risk for affective disorders and physical health problems among women [17, 18]. Together, these findings tentatively suggest that for both the PRS-SCZ and ES-SCZ, epidemiological associations with health measures may not be uniform across ages and sexes.

We thus aimed to examine whether age and sex moderate the associations between risk scores for schizophrenia and self-reported health in a general population-based cohort. We considered two risk scores (PRS-SCZ and ES-SCZ) and two outcomes (self-reported mental and physical health). We also aimed to explore whether the interactions between risk scores and age differed according to sex (three-way interactions).

Materials and methods

Participants

Participants were from the Netherlands Mental Health Survey and Incidence Study–2 (NEMESIS-2), which was designed to investigate the prevalence, incidence, course, and consequences of mental disorders in the Dutch general population [19, 20]. The study was approved by the Medical Ethics Review Committee for Institutions on Mental Health Care (METIGG). All participants provided written informed consent.

Participants were recruited according to a multistage random sampling procedure to ensure representativeness for age (between 18 and 65 years), region, and population density [19]. Individuals not proficient in Dutch were excluded. Participants were assessed by trained interviewers on four occasions between 2007 and 2018: at baseline (T0), at year 3 (T1), at year 6 (T2) and at year 9 (T3). The first wave (T0) included 6646 participants (response rate 65.1%; average interview duration: 95 min). Subsequent response rates were 80.4% at T1 (N = 5303; excluding those who deceased; average interview duration: 84 min), 87.8% at T2 (N = 4618; interview duration: 83 min), and 87.7% at T3 (N = 4007; interview duration: 101 min). Attrition between T0 and T3 was associated with younger age, lower educational attainment, unemployment, and being born outside the Netherlands [21]. There was no association of attrition with baseline 12-month common mental disorders (after adjusting for sociodemographic characteristics) nor with having any chronic physical disorder.

Measures

Mental and physical health outcomes

Health outcomes were measured at T0, T1, T2, and T3 with the 36-item Short Form Survey (SF-36) [22]. The SF-36 includes 8 subscales, each ranging from poor (0) to good (100) health. Based on previous validation studies of the questionnaire in community-based and clinical samples [22, 23], we aggregated the subscales into 2 general measures of mental and physical health: (1) the “mental health”, “role limitations due to emotional problems”, “social functioning”, and “vitality” subscales were averaged into a single mental health score, and (2) the “general health”, “physical functioning”, “role limitation due to physical health problems”, and “bodily pain” subscales were averaged into a single physical health score.

Polygenic risk score for schizophrenia

Details on the genotyping procedure are presented in the Supplementary Material. For PRS-SCZ, we selected schizophrenia-associated genetic loci according to a P-threshold of < 0.05 because this threshold best captures liability to the disorder according to the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium analysis [24]. With the same cohort and measures as the current study, we previously reported that higher PRS-SCZ was significantly associated with poorer mental health, but not significantly associated with physical health; these associations did not account for potential interactions with age or sex [8].

Exposome score for schizophrenia

For ES-SCZ, we selected eight exposures from T0 which we aggregated following a previously validated method [3]. These exposures were cannabis use, winter birth, hearing impairment, and five domains of childhood adversity. Cannabis use was defined as one use per week or more in the period of most frequent use (lifetime) and was measured with the Illegal Substance Use section of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview 3.0 [25, 26]. Winter birth was defined as birth between December and March. Hearing impairment was reported by participants for the past 12 months. Participant reports of childhood adversity were collected with the modified NEMESIS-1 trauma questionnaire [19] and were divided in five domains: emotional abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional neglect, and bullying. We coded all exposures as present = 1 or absent = 0. ES-SCZ was calculated by summing these exposures, each weighted by their schizophrenia-associated log odds in an external sample (total range 0–5.95, with higher values indicating higher risk for schizophrenia) [3]. With the same cohort and measures as the current study, we previously reported that higher ES-SCZ was significantly associated with poorer mental and physical health [8], but these associations did not account for potential interactions with age or sex.

Statistical analysis

Analyses were conducted in R version 3.6.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing). We defined nominal statistical significance as p < 0.05. We excluded participants who had missing data on modeled variables at baseline; those with complete baseline data were included even if they were subsequently lost to follow-up. To evaluate the potential impact of excluding participants on our analyses, we compared sociodemographic characteristics of included participants with those of excluded participants.

To examine age- and sex-specific associations between “risk” scores and mental health or physical health outcomes, we applied linear mixed models using the nlme package [27]. Rather than focusing on cross-sectional measures of mental and physical health at T0, we analyzed the repeated measures of these outcomes over time to capture some of their within-individual variance. Of note, linear mixed models are robust to attrition over follow-up if missingness is at random. Due to the temporal dependency between outcome measures, we applied an autoregressive correlation structure of order 1 [27]. We adjusted for the timing of outcome ranging from 0–9 years since T0. In analyses of age as the moderator, we included age fixed at T0 as a time-invariant predictor spanning 18 through 65 years of age, the risk score (either PRS-SCZ or ES-SCZ), and the interaction between the risk score and age at T0. For all analyses of age, quadratic effects of age and their interaction with risk scores improved model fit by a reduction of ≥ 10 of the Akaike Information Criterion and were thus included [28]. In analyses of sex as the moderator, we included a dichotomous variable for sex, the risk score, and the interaction between the risk score and sex. We standardized (mean = 0, SD = 1) the PRS-SCZ, ES-SCZ, and outcome variables. We divided age by 10 to reduce its scaling difference relative to other variables (but transformed it back to its original scale in the figures). In PRS-SCZ models, we adjusted for the first three principal components which we also standardized. We probed interaction effects by estimating the marginal trend of outcome associated with 1 SD increase in the risk score at different levels of the moderator (age or sex) [29].

When interactions between ES-SCZ and age or sex were statistically significant, we conducted a sensitivity analysis to explore their stability. We did so by testing the same interactions but using eight variations of the ES-SCZ, each omitting one of the 8 schizophrenia-associated exposures. Lastly, to explore whether interactions between PRS-SCZ or ES-SCZ and age differed between participants of male and female sexes, we tested three-way interactions between the risk scores, age, and sex.

Results

Interactions between the polygenic risk score for schizophrenia and age or sex

Of 6646 participants enrolled in NEMESIS-2, 3099 (46.6%) had complete baseline data for analyses involving the PRS-SCZ and were thus included in these analyses. Included participants had a mean (SD) age of 44.1 (12.5) years and 56.1% were female. As shown in Table 1, included participants were more likely to have higher educational attainment compared with excluded participants, but they did not significantly differ on other characteristics.

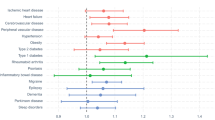

Table 2 presents the PRS-SCZ × age and PRS-SCZ × sex interaction terms. For both the mental health and physical health outcomes, there was no significant interaction of PRS-SCZ with age or sex. Figure 1 (upper row) illustrates the associations between PRS-SCZ and outcomes according to the age of participants. The trends on Fig. 1 suggest that PRS-SCZ was associated with poorer mental health, particularly at younger ages, and poorer physical health, particularly at the “extremes” of the age interval (18–65 years); however, as illustrated by the confidence intervals that largely overlap across ages, these age-specific patterns were not statistically significant for both mental and physical health. Supplementary Table 1 presents associations between PRS-SCZ and outcomes according to sex. Sex did not moderate the interactions between PRS-SCZ and age (Fig. 2).

Interactions between schizophrenia risk scores and age associated with mental health or physical health. PRS-SCZ indicates polygenic risk score for schizophrenia (upper row). ES-SCZ indicates exposome score for schizophrenia (lower row). Outcomes were mental health (on the left) and physical health (on the right) as measured with the 36-item Short Form Survey. Using linear mixed models, we estimated the trend between PRS-SCZ or ES-SCZ and the outcomes at various ages, including linear and quadratic effects of age on these trends

Three-way interactions between schizophrenia risk scores, age and sex associated with mental health or physical health. PRS-SCZ indicates polygenic risk score for schizophrenia (upper row). ES-SCZ indicates environmental risk score for schizophrenia (lower row). Outcomes were mental health (on the left) and physical health (on the right) as measured with the 36-item Short Form Survey. Using linear mixed models, we estimated the trend between PRS-SCZ or ES-SCZ and the outcomes at various ages, including linear and quadratic effects of age on these trends, and according to sex

Interactions between the exposome score for schizophrenia and age or sex

Of the total cohort, 6264 participants (94.2%) had complete baseline data for analyses involving the ES-SCZ. Included participants had a mean (SD) age of 44.5 (12.4) years and 55.7% were female. As shown in Table 1, included participants were more likely to be female and to have higher educational attainment compared with excluded participants. Inclusion was also associated with higher age and higher scores for mental health and physical health.

Coefficients for interactions between ES-SCZ and age or sex are presented in Table 3. For mental health, there was a significant interaction between ES-SCZ and age (through both its linear and quadratic terms). As shown in Fig. 1 (bottom left), higher ES-SCZ was significantly associated with lower mental health levels, and this negative association was of greater magnitude among older participants. To illustrate, at age 18, higher ES-SCZ by 1.00 SD was associated with lower mental health by 0.10 SD, whereas at age 65, the same increase in ES-SCZ was associated with lower mental health by 0.21 SD. The interaction between ES-SCZ and age had a similar pattern in all 8 sensitivity analysis models using variations of the ES-SCZ (Supplementary Fig. 1). Across these models, the interaction between ES-SCZ and age, either through its linear or quadratic term, was significant (Supplementary Table 2). There was no interaction between ES-SCZ and sex (Table 3, Supplementary Table 1). The three-way interaction between ES-SCZ, age, and sex was not significant (Fig. 2): coefficient (with linear age) = 0.11 (95% CI − 5.45, 5.67), p = 0.97, and coefficient (with quadratic age) = 3.35 (95% CI − 2.31, 9.02), p = 0.25.

For physical health, there was a significant interaction between ES-SCZ and the linear term for age (Table 3). Higher ES-SCZ was significantly associated with lower physical health levels, and this association was of greater magnitude among older participants (Fig. 1, bottom right). At age 18, higher ES-SCZ by 1.00 SD was associated with lower physical health by 0.08 SD; at age 65, higher ES-SCZ by 1.00 SD was associated with lower physical health by 0.23 SD. The interaction between ES-SCZ and linear age remained significant across variations of the ES-SCZ after alternately omitting individual exposures from ES-SCZ; one exception was after omitting cannabis use (interaction coefficient: p = 0.09; Supplementary Table 3). A consistent interaction pattern was nonetheless identified in all 8 sensitivity analysis models, including the one omitting cannabis use (Supplementary Fig. 2). Next, there was a significant interaction between ES-SCZ and sex (Table 3). Higher ES-SCZ was associated with lower physical health, and this association was of greater magnitude among female participants (Supplementary Table 1): in female participants, higher ES-SCZ by 1.00 SD was associated with lower physical health by 0.19 SD, whereas in male participants, higher ES-SCZ by 1.00 SD was associated with lower physical health by only 0.11 SD. In sensitivity analyses, this interaction remained significant and was in the same direction for all 8 models (Supplementary Table 4). The three-way interaction between ES-SCZ, age, and sex was not nominally significant: coefficient (with linear age) = − 0.70 (95% CI − 6.45, 5.04), p = 0.81, and coefficient (with quadratic age) = 5.52 (95% CI − 0.33, 11.38), p = 0.06. However, visual probing of the interaction (Fig. 2, bottom right) suggests that the interaction between ES-SCZ and age (i.e., a greater association between ES-SCZ and physical health as a function of older age) was specific to female individuals.

Discussion

The association between exposomic liability to schizophrenia and poorer mental and physical health was greater with older age. To our knowledge, this is the first study to explore whether exposomic liability to schizophrenia has age-specific associations with health. One explanation for this finding is that the health influences of schizophrenia-associated exposures may accumulate over the lifespan. In NEMESIS-2, we previously found that ES-SCZ was associated with multiple mental and physical conditions, such as social phobia, asthma, joint wear and heart disease [5], which typically emerge at various ages. The age-dependent trends of ES-SCZ may thus reflect cumulative incidence of health conditions throughout adulthood.

The association between ES-SCZ and physical health was also greater among female individuals. Sex or gender differences are often identified in the associations between risk factors for schizophrenia and health, although sometimes inconsistently. To illustrate, in a survey of middle-aged adults, childhood adversity was preferentially associated with obesity, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease among men, and with insomnia and cancer among women [30]. Another study found the opposite pattern, concluding that childhood adversity was more strongly associated with heart disease in women [17]. Cannabis use, childhood adversity, and other exposures have displayed sex-specific associations with mental health in previous research [31, 32], yet we observed an interaction with sex for physical health only, and not for mental health. Ultimately, mechanisms for these sex differences are complex and may include multiple social and environmental factors, genes, neurodevelopmental trajectories, immune responses, and gonadal hormones, and the relative contribution of these mechanisms may be heterogeneous depending on population characteristics, measurements, and outcome selection [11, 31].

The associations between PRS-SCZ and health measures did not interact with age or sex. Genetic variants conferring risk for schizophrenia have been associated with multiple mental and physical health outcomes [6, 33, 34]: for example, in an electronic health record study of 106,160 adults in the US, higher PRS-SCZ was associated with higher risk of mood and anxiety disorders, neurological conditions, and urinary syndromes, as well as lower risk of synovitis and obesity [6]. There is however limited literature on interactions between PRS-SCZ and age. Perhaps the study most comparable to the current analysis comes from a longitudinal cohort, where PRS-SCZ was associated with IQ at age 70, but not at age 11 [12]. Considering that neurodevelopment may underlie shifts in the correlates of PRS-SCZ between ages of 11 and 70, it is unclear if a similar interaction would apply to the age range of the current study (18–65 years old), and if it would extend to the broader health measures we examined. As for genetic heterogeneity by sex, a recent genome-wide analysis study of schizophrenia found no evidence thereof [35]. Another study found evidence of greater expression of schizophrenia-associated genes in male compared with female brains [36]. Further, the PRS-SCZ has displayed male-specific associations with neural connectivity [37], schizotypy [14], and cognitive task performance [13] in other work. Our negative findings may reflect a true absence of interaction between PRS-SCZ and age or sex, but they may also be due to insufficient statistical power. As mentioned in the introduction, the association between PRS-SCZ and health in the general population is weak at best, and statistical power decreases dramatically for interaction effects of the same magnitude [38]. Thus, our sample size and the PRS-SCZ’s predictive performance may still be insufficient to reliably detect interactions.

Overall, we provide preliminary evidence of age- and sex-specific associations between ES-SCZ and self-reported health in the general population. As these findings and the other studies cited above illustrate, risk factors for schizophrenia have transdiagnostic correlates. They are not only associated with schizophrenia risk, but also with other mental and physical health outcomes across the lifespan [5, 6, 8]. In recent years, the ES-SCZ has been combined with other predictive variables to study the risk architecture of symptom profiles, illness status, and health outcomes across clinical and non-clinical samples [4]. By aggregating exposures associated with the liability to schizophrenia, the ES-SCZ offers a practical approach to capturing the additive and interdependent effects of multiple exposures on health. Alongside other clinical and biological data, exposomic liability to schizophrenia may help advance the personalization of early intervention services–not only as an index of psychosis risk, but also of other diagnostic categories and domains of health [39]. Yet while environmental exposures have sizeable health correlates, these properties may be highly contingent on other factors, from the biological to the social. Appreciating interactions between exposome scores and sociodemographic factors, including age and sex, should thus be considered for the scores to perform optimally across various populations, and to increase our understanding of the pathways underlying non-specific exposomic associations with health.

Strengths and limitations

A strength of the study is that we examined exposomic liability to schizophrenia in a large sample drawn from the general Dutch population. Not surprisingly given the sample size, there were statistically significant differences in baseline characteristics after excluding participants with missing data. But considering the relatively small magnitude of differences, external validity may still be reasonable for the target population [19]. For genetic analyses, however, the representativeness of our sample was limited: we excluded individuals of non-European ancestries because the PRS-SCZ we used is only valid for populations of European ancestry [2].

We analyzed interactions with age according to between-individual rather than within-individual differences in age because participants were followed over less than a decade. The advantage of this is that the wide age interval of participants at baseline (18–65 years old) allowed us to capture moderation by age across most of the adult life period. The limitation of this approach is that it prevented us from differentiating interactions with age (that would arise from longitudinal health changes within individuals as they age) from interactions with the period of birth. The health correlates of ES-SCZ may vary as a function of the period of birth due to historical factors [40,41,42]. Here, study participants aged 18 years at baseline (2007–2009) were born in 1989–1991, while those aged 65 were born in 1942–1944. Although the time span was relatively short, we cannot exclude a possible contribution of generational differences to the interaction between ES-SCZ and age.

Measures included sex but not gender, and both constructs are relevant to untangle the social and biological factors that may play a role in moderating the association between risk scores for schizophrenia and health. As for outcomes, we benefitted from repeated measures over time to increase the precision of the statistical models. We focused on self-reported mental and physical health, two broad constructs that are meaningful across the lifespan in the general population. But to develop a more granular understanding of interactions between ES-SCZ or PRS-SCZ and age and sex, further work should examine the incidence of specific clinical outcomes during relevant age periods (e.g., cardiac disease from mid-adulthood onwards).

Finally, due to the challenges of identifying and validating consistent measures of exposures across distinct samples, ES-SCZ is composed of only a handful of the risk factors for schizophrenia; inclusion of additional exposures, such as perinatal adversity [11], could increase its predictive performance and influence its interactions with age and sex. But while the ES-SCZ is calculated from only eight exposures, its interactions with age and sex were largely robust to omitting single exposures, suggesting relatively stable age- and sex-specific trends. The interaction between ES-SCZ and age was also consistent across both mental and physical health, further supporting the robustness of this finding.

In conclusion, we found that ES-SCZ, but not PRS-SCZ, interacted with age and sex in association with self-reported health in a Dutch population-based cohort. Our findings support the relevance of considering whether population characteristics moderate the transdiagnostic associations between exposome scores and health.

Data availability

The data on which this manuscript is based are not publicly available. However, data from NEMESIS-2 are available upon request. The Dutch ministry of health financed the data and the agreement is that these data can be used freely under certain restrictions and always under supervision of the principal investigator (PI) of the study. Thus, some access restrictions do apply to the data. At any time, researchers can contact the PI of NEMESIS-2 and submit a research plan, describing its background, research questions, variables to be used in the analyses, and an outline of the analyses. If a request for data sharing is approved, a written agreement will be signed stating that the data will only be used for addressing the agreed research questions described and not for other purposes.

References

Wray NR, Lin T, Austin J et al (2021) From basic science to clinical application of polygenic risk scores: a primer. JAMA Psychiat 78:101. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.3049

Ripke S, Neale BM, Corvin A et al (2014) Biological insights from 108 schizophrenia-associated genetic loci. Nature 511:421–427. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13595

Pries L-K, Lage-Castellanos A, Delespaul P et al (2019) Estimating exposome score for schizophrenia using predictive modeling approach in two independent samples: the results from the EUGEI Study. Schizophr Bull 45:960–965. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbz054

Erzin G, Guloksuz S (2021) The exposome paradigm to understand the environmental origins of mental disorders. Alpha Psychiatry 22:171–176. https://doi.org/10.5152/alphapsychiatry.2021.21307

Pries L-K, Erzin G, van Os J et al (2021) Predictive performance of exposome score for schizophrenia in the general population. Schizophr Bull 47:277–283. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbaa170

Zheutlin AB, Dennis J, Karlsson Linnér R et al (2019) Penetrance and pleiotropy of polygenic risk scores for schizophrenia in 106,160 patients across four health care systems. Am J Psychiatry 176:846–855. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2019.18091085

Marsman A, Pries L-K, Ten Have M et al (2020) Do current measures of polygenic risk for mental disorders contribute to population variance in mental health? Schizophr Bull 46:1353–1362. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbaa086

Pries L-K, van Os J, ten Have M et al (2020) Association of recent stressful life events with mental and physical health in the context of genomic and exposomic liability for schizophrenia. JAMA Psychiat 77:1296. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.2304

Murray GK, Lin T, Austin J et al (2021) Could polygenic risk scores be useful in psychiatry? A review. JAMA Psychiat 78:210–219. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.3042

Binder EB (2019) Polygenic Risk scores in schizophrenia: ready for the real world? AJP 176:783–784. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2019.19080825

Paquin V, Lapierre M, Veru F, King S (2021) Early environmental upheaval and the risk for schizophrenia. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 17:285–311

McIntosh AM, Gow A, Luciano M et al (2013) Polygenic risk for schizophrenia is associated with cognitive change between childhood and old age. Biol Psychiatry 73:938–943. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.01.011

Koch E, Nyberg L, Lundquist A et al (2021) Sex-specific effects of polygenic risk for schizophrenia on lifespan cognitive functioning in healthy individuals. Transl Psychiatry 11:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-021-01649-4

Docherty AR, Shabalin AA, Adkins DE et al (2020) Molecular genetic risk for psychosis is associated with psychosis risk symptoms in a population-based UK cohort: findings from generation Scotland. Schizophr Bull 46:1045–1052. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbaa042

Stepniak B, Papiol S, Hammer C et al (2014) Accumulated environmental risk determining age at schizophrenia onset: a deep phenotyping-based study. Lancet Psychiatry 1:444–453. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(14)70379-7

O’Donoghue B, Lyne J, Madigan K et al (2015) Environmental factors and the age at onset in first episode psychosis. Schizophr Res 168:106–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2015.07.004

Friedman EM, Montez JK, Sheehan CM et al (2015) Childhood adversities and adult cardiometabolic health: does the quantity, timing, and type of adversity matter? J Aging Health 27:1311–1338. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898264315580122

Chartier MJ, Walker JR, Naimark B (2010) Separate and cumulative effects of adverse childhood experiences in predicting adult health and health care utilization. Child Abuse Negl 34:454–464. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.09.020

de Graaf R, Ten Have M, van Dorsselaer S (2010) The Netherlands mental health survey and Incidence study-2 (NEMESIS-2): design and methods. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 19:125–141. https://doi.org/10.1002/mpr.317

de Graaf R, ten Have M, van Gool C, van Dorsselaer S (2012) Prevalence of mental disorders and trends from 1996 to 2009. results from the Netherlands mental health survey and incidence study-2. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 47:203–213. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-010-0334-8

de Graaf R, van Dorsselaer S, Tuithof M, ten Have M (2013) Sociodemographic and psychiatric predictors of attrition in a prospective psychiatric epidemiological study among the general population result of the Netherlands mental health survey and incidence study-2. Compr Psychiatry 54:1131–1139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2013.05.012

Ware JE, Gandek B (1998) Overview of the SF-36 health survey and the international quality of life assessment (IQOLA) Project. J Clin Epidemiol 51:903–912. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0895-4356(98)00081-X

Loge JH, Kaasa S (1998) Short form 36 (SF-36) health survey: normative data from the general Norwegian population. Scand J Soc Med 26:250–258

Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium (2014) Biological insights from 108 schizophrenia-associated genetic loci. Nature 511:421–427. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13595

Alonso J, Angermeyer MC, Bernert S et al (2004) Sampling and methods of the European study of the epidemiology of mental disorders (ESEMeD) project. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0047.2004.00326

de Graaf R, Ormel J, ten Have M et al (2008) Mental disorders and service use in the Netherlands: results from the European study of the epidemiology of mental disorders (ESEMeD). The WHO world mental health surveys: global perspectives on the epidemiology of mental disorders. Cambridge University Press, New York, pp 388–405

Pinheiro J, Bates D, R-core (2021) nlme: Linear and nonlinear mixed effects models

Burnham KP, Anderson DR (2004) Multimodel inference: understanding AIC and BIC in model selection. Sociol Methods Res 33:261–304. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124104268644

Lenth RV, Buerkner P, Herve M et al (2021) Emmeans: estimated marginal means, aka least-squares means. R package version 1.5.5-1

Kuhlman KR, Robles TF, Bower JE, Carroll JE (2018) Screening for childhood adversity: the what and when of identifying individuals at risk for lifespan health disparities. J Behav Med 41:516–527. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-018-9921-z

Bale TL, Epperson CN (2015) Sex differences and stress across the lifespan. Nat Neurosci 18:1413–1420. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.4112

Wainberg M, Jacobs GR, di Forti M, Tripathy SJ (2021) Cannabis, schizophrenia genetic risk, and psychotic experiences: a cross-sectional study of 109,308 participants from the UK Biobank. Transl Psychiatry 11:211. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-021-01330-w

Abdellaoui A, Verweij KJH (2021) Dissecting polygenic signals from genome-wide association studies on human behaviour. Nat Hum Behav 5:686–694. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01110-y

Richardson TG, Harrison S, Hemani G, Davey Smith G (2019) An atlas of polygenic risk score associations to highlight putative causal relationships across the human phenome. eLife 8:e43657. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.43657

Trubetskoy V, Pardiñas AF, Qi T et al (2022) Mapping genomic loci implicates genes and synaptic biology in schizophrenia. Nature 604:502–508. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-04434-5

Shi L, Zhang Z, Su B (2016) Sex biased gene expression profiling of human brains at major developmental stages. Sci Rep 6:21181. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep21181

Meyers JL, Chorlian DB, Bigdeli TB et al (2021) The association of polygenic risk for schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and depression with neural connectivity in adolescents and young adults: examining developmental and sex differences. Transl Psychiatry 11:54. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-020-01185-7

Brookes ST, Whitely E, Egger M et al (2004) Subgroup analyses in randomized trials: risks of subgroup-specific analyses. J Clin Epidemiol 57:229–236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2003.08.009

Shah JL, Jones N, van Os J et al (2022) Early intervention service systems for youth mental health: integrating pluripotentiality, clinical staging, and transdiagnostic lessons from early psychosis. Lancet Psychiatry 9:413–422. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00467-3

Tucker-Drob EM, Briley DA, Harden KP (2013) Genetic and environmental influences on cognition across development and context. Curr Dir Psychol Sci 22:349–355. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721413485087

Min J, Chiu DT, Wang Y (2013) Variation in the heritability of body mass index based on diverse twin studies: a systematic review. Obes Rev 14:871–882. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.12065

Silventoinen K, Jelenkovic A, Sund R et al (2020) Genetic and environmental variation in educational attainment: an individual-based analysis of 28 twin cohorts. Sci Rep 10:12681. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-69526-6

Funding

NEMESIS-2 is conducted by the Netherlands Institute of Mental Health and Addiction (Trimbos Institute) in Utrecht. The funder had no role in the design and conduct. Financial support has been received from the Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport, with supplementary support from the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (ZonMw). This work was supported by the European Community’s Seventh Framework Program under grant agreement No. HEALTH-F2-2009-241909 (Project EU-GEI). These funding sources had no further role in study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the paper for publication. B.P.F.R. was funded by a VIDI award number 91718336 from the Netherlands Scientific Organisation. S.G. and J.v.O. are supported by the Ophelia research project, ZonMw grant number: 636340001. M.O. is supported by MRC programme grant (G08005009) and an MRC Centre grant (MR/L010305/1).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

M.O. is supported by a collaborative research grant from Takeda Pharmaceuticals. Takeda played no part in the conception, design, implementation, funding or interpretation of this paper. No other disclosures were reported.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Paquin, V., Pries, LK., ten Have, M. et al. Age- and sex-specific associations between risk scores for schizophrenia and self-reported health in the general population. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 58, 43–52 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-022-02346-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-022-02346-3