Abstract

Purpose

We aimed to estimate the structure of internalizing and externalizing symptoms and potential time dynamics in their association. This is understudied among adolescents, despite increasing internalizing and decreasing externalizing symptoms in recent years.

Methods

We analyzed data from US Monitoring the Future cross-sectional surveys (1991–2018) representative of school-attending adolescents (N = 304,542). Exploratory factor analysis using maximum likelihood estimation method and promax rotation resulted in a two-factor solution (factor correlation r = 0.24) that differentiated eight internalizing and seven conduct-related externalizing symptoms. Time-varying effect modification linear regression models estimated the association between standardized internalizing and externalizing symptoms factor scores over time overall and by gender.

Results

In 2012, trends in average factor scores diverged for internalizing and externalizing factors. The average standardized internalizing factor score increased from − 0.03 in 2012 to 0.06 in 2013 and the average externalizing factor score decreased from − 0.06 in 2011 to − 0.13 in 2012. We found that for every one-unit increase in standardized internalizing factor score, standardized externalizing factor score increased by 0.224 units in 2010 (95% CI: 0.215, 0.233); the magnitude of this increase was 22.3% lower in 2018 (i.e., 0.174 units; 95% CI: 0.160, 0.188). Decoupling of internalizing and externalizing symptoms began earlier among boys (~ 1995) than among girls (~ 2010).

Conclusion

The decoupling of internalizing and externalizing symptoms among adolescents suggests that changes in the prevalence of shared risk factors for adolescent psychiatric symptoms affect these dimensions in opposing directions, raising the importance of considering symptoms and their risk factors together in prevention and intervention efforts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Internalizing and externalizing symptoms form the foundation of common psychiatric disorders such as anxiety, depressive, and conduct disorders [1,2,3]. Internalizing symptoms include those related to anxiety and depression [4] and focus on internal expression of distress [5]. Externalizing symptoms are directed outwardly [5] and include those related to conduct, aggression, and delinquency [6]. Internalizing and externalizing symptoms are associated with a variety of other negative health and social consequences, such as suicide [7, 8], substance use [9, 10], overdose-related premature death [11, 12], and higher rates of incarceration [13]. Transdiagnostic models used to explain high prevalence of disorder comorbidity are consistent with the existence of distinct yet correlated internalizing and externalizing psychopathology dimensions. The distinct dimensions explain the higher correlation within internalizing symptoms (and within externalizing symptoms) than between internalizing and externalizing symptoms [14,15,16,17]. The two-dimension structure of internalizing and externalizing symptoms has been replicated for decades [5, 18,19,20]. However, time trends in factor scores have been understudied, particularly in adolescence, which is a critical developmental period with a high risk of psychiatric disorder onset [21, 22].

Historically, comorbidity between internalizing and externalizing symptoms is high in adolescents [23,24,25,26], with some gender differences in symptom prevalence [27] and internalizing symptoms begin prior to externalizing symptoms [28, 29]. However, recent changes in the prevalence of internalizing and externalizing symptoms raise questions about the magnitude of their association dynamically changing over recent time. Significant increases in adolescent internalizing symptoms have been documented across numerous data sources [27, 30,31,32]. For example, emergency department visits due to suicide attempts and ideation among adolescents increased almost twofold from 2007 to 2015 [33]. Conversely, trends in adolescent externalizing symptoms, such as conduct-related symptoms [34], binge drinking and many drugs [35, 36], have been decreasing over time [34, 37, 38]. Despite the divergence in internalizing and externalizing symptom trends over time, no literature has examined whether the association between internalizing and externalizing symptoms is dynamic and to what extent (i.e., strengthening of ties or dissipation). Previous research has focused on these trends separately rather than concurrently despite the fact that the association between internalizing and externalizing symptoms is well-documented [39]. Understanding the association between internalizing and externalizing symptoms over time could stimulate further research on potential causal mechanisms leading to divergent population trends.

Time trends in internalizing and externalizing symptoms separately vary across certain demographic sub-groups, such as gender. Internalizing symptoms, and major depressive episodes have been increasing among both adolescent girls and boys, but faster for girls, particularly after 2012 [27, 40]. In addition to depressive episodes, suicide has increased at a faster rate among adolescent girls compared to boys [41]. Other internalizing symptoms, such as low self-esteem symptoms, have been increasing rapidly from 2010 onwards among adolescent girls [32]. On the other hand, externalizing symptoms, such as conduct behaviors [34] and deviant behaviors [38], have decreased at a faster rate among adolescent boys compared to girls [42]. However, there is a gap in the literature about whether these gender differences in time trends persist when examining the change in the association between internalizing and externalizing symptoms over time among adolescents.

There are two potential scenarios that could explain the relationship between the trends in adolescent internalizing and externalizing symptoms. The strength in the relationship between internalizing and externalizing symptoms could be increasing over time while trends are diverging in overall direction. Among adolescents who develop externalizing symptoms, for example, there could be a higher concentration of co-morbid internalizing symptoms over time, which would lead to a strengthening of the association. Conversely, the relationship between internalizing and externalizing symptoms could be weakening over time. This could indicate that there are different underlying mechanisms driving these diverging trends rather than the same mechanism causing internalizing symptoms to increase and externalizing symptoms to decrease. If time trends in the association differ by gender, different gender-specific underlying mechanisms could be driving the changes in internalizing and externalizing symptom prevalence over time and vice versa. This could have implications for how clinicians screen for internalizing/externalizing symptoms and diagnose related psychiatric disorders in a subset of these adolescents. If the association between internalizing and externalizing symptoms among adolescents with mental health disorders is changing (e.g., weakening) over time, strategies to detect mental health needs among adolescents may need to be refined to ensure adequate allocation of services.

The objectives of this study were to (1) characterize the relationship between internalizing and externalizing symptoms in a large, nationally representative dataset of adolescent students from 1991 to 2018; (2) describe time trends in the relationship between internalizing and externalizing symptoms; and (3) assess whether there are differences in time trends in the relationship between adolescent internalizing and externalizing symptoms between adolescent boys and girls. Understanding whether these relationships have changed over time is an important public health priority that could inform the types of interventions needed to mitigate adolescent internalizing and externalizing symptoms (e.g., interventions that are tailored to internalizing or externalizing symptoms separately or interventions that address both types of symptoms together), overall and by gender.

Methods

Sample

Public-use data from the Monitoring the Future (MTF) study included cross-sectional annual surveys from 8th, 10th, and 12th-grade adolescent students in the continental United States from 1991 to 2018 [43]. A multistage random sampling design was used to select schools. School participation rates were between 91 and 99% from 1991 to 2018. Individual student response rates were 86.5% on average. Student non-response was mostly due to absenteeism and < 1% of students declined participation. All students completed a questionnaire with a core set of questions, then students received randomly assigned additional question sub-forms. Further information on sampling design and implementation procedures can be found elsewhere [42].

The study sample was restricted to adolescents who received sub-forms that included both externalizing and internalizing symptom questions from 1991 to 2018 and who answered at least one item from each symptom sub-scale (conduct externalizing symptoms, self-esteem, and self-derogation internalizing symptoms; N = 403,647). Among adolescents who received relevant sub-forms, 320,783 (79.5% of the total sample) had complete data for all internalizing/externalizing variables of interest. Item non-response for internalizing/externalizing variables of interest ranged from an average of 13.5% to 15.3% across all years. Of the 82,864 observations missing any internalizing/externalizing data, we replaced missing values for those with only one missing item from a given sub-scale (n = 13,427, 3.3% of the total sample) with the average value of the other items on that sub-scale, bringing the overall analytic sample size to 334,210. We excluded observations with two or more items missing from a given sub-scale (n = 69,437 deleted due to missing 2 + items, 17.2% of the total sample) or missing covariate data (n = 29,668; 7.3% of the total sample). Our final analytic sample was 304,542 adolescents, which was 94.9% of the sample who received sub-forms with internalizing/externalizing questions.

Measures

Self-esteem and self-derogation internalizing symptoms. Eight items were utilized to assess internalizing symptoms. After the initial question of “How much do you agree or disagree with each of the following statements,” adolescents responded to the following items: “I take a positive attitude toward myself,” “I feel I am a person of worth, on an equal plane with others,” “I am able to do things as well as most other people,” “On the whole, I'm satisfied with myself,” “I feel I do not have much to be proud of”, “Sometimes I think that I am no good at all”, “I feel that I can't do anything right”, “I feel that my life is not very useful.” Response options ranged from 1 (disagree) to 5 (agree). The first four items were reverse coded. Internalizing symptom inter-item correlation was high (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.87). Average scores ranged from 1.88 to 2.33 for these eight items after reverse coding the first four items, indicating that the average score was close to the “mostly agree” response option for the first four items and the “mostly disagree” response option for the latter four items.

Conduct-related externalizing symptoms. Seven items were utilized to assess externalizing symptoms. After the initial question of “During last 12 months, how often have you...” adolescents responded to the following items: “taken something not belonging to you worth under $50,” “taken something not belonging to you worth over $50,” “gone into some house or building when you weren't supposed to be there,” “damaged school property on purpose,” “gotten into a serious fight in school or at work,” “taken part in a fight where a group of your friends were against another group,” and “hurt someone badly enough to need bandages or a doctor.” Response options ranged from 1 (not at all) to 5 (5 or more times). Externalizing symptom inter-item correlation was high (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.81). Average scores ranged from 1.19 to 1.52, showing that the average score was approximately the “not at all” to “once” response options.

Sociodemographic variables included grade (8th/10th/12th), self-identified gender (response options restricted to male/female adolescents), grade point average (B- or less/B or greater), and parental education to approximate socioeconomic status (highest level of education for either the mother or father; some high school or lower/high school graduate or some college/college graduate or higher).

Statistical analyses

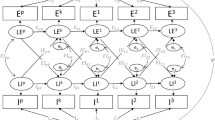

Descriptive analyses examined average symptom ratings overall and by gender. Next, exploratory factor analysis was conducted utilizing maximum likelihood estimation and promax rotation methods. Model fit was assessed by examining AIC/BIC values with lower values indicating better fit. The final model was selected based on model fit, parsimony, and interpretability. Results from an additional model displaying a three-factor solution are displayed in supplemental materials. We selected the two-factor solution over the three-factor solution to examine internalizing symptoms as one domain and describe trends broadly instead of separating internalizing symptoms into sub-domains of self-esteem and self-derogation. Factor scores were standardized to ensure that changes in beta coefficients do not merely reflect changes in standard deviations of internalizing and externalizing symptom factor scores, and mean factor scores were plotted over time overall and by gender. Correlation between standardized factor scores was assessed by year, both overall and by gender.

Time-varying effect modeling (TVEM) was utilized to quantify associations between internalizing and externalizing factor scores over time, based on the two-factor solution selected. TVEM is a modeling technique that can analyze the functional form of associations over a continuous time period without making parametric assumptions [44, 45]. TVEM assumes that the associations change fluidly rather than suddenly over time [46]. We utilized the unweighted %TVEM SAS macro version 3.1.1 for this analysis [46].

We fit our model with internalizing symptoms as the independent variable and externalizing symptoms as the dependent variable. Linear regression models were used to assess the association between internalizing and externalizing symptoms over time with year operationalized as a continuous, fluid time function from 1991 to 2018. Within the TVEM figures 10 knots per covariate were used to fit splines [46]. The figure presented the coefficient functions with point-wise confidence intervals (CIs) with a dashed line at 0.0 to indicate a null relationship threshold. Empirical sandwich estimators were utilized with p-splines that auto-selected an appropriate amount of smoothness based on lowest BIC value [46]. After assessing the relationship between internalizing and externalizing symptoms among the overall sample, linear regressions utilizing TVEM were run stratified by gender. Data management and TVEM were conducted using SAS v9.4 and factor analysis was conducted using STATA v15. Further analyses assessing changes in internalizing and externalizing symptom severity group (low internalizing and low externalizing symptom factor scores, high internalizing symptom factor score only, high externalizing symptom factor score only, and high internalizing and externalizing factor scores) over time are presented in supplemental materials. Multinomial logistic regression models examined associations between these severity groups and: demographic characteristics included in the main analysis, decade (1990s, 2000s, 2010s), and three additional substance use measures (past 2-week binge drinking; past 30-day cannabis, cigarette, or other drug use). Subsequently, models assessed interactions between decade and substance use measures, accounting for demographic characteristics, using linear combinations to estimate substance use within decade (i.e., adding decade, substance use, and interaction estimates).

Sensitivity analyses

TVEM figures were also run with externalizing symptom factor score as the independent variable and internalizing symptom factor score as the dependent variable to see if this would alter our findings.

Results

Factor analysis results for the selected two-factor solution are displayed in Table 1. Among the 304,542 school-attending adolescents from 1991–2018 that were included in our final analytic sample, conduct-related externalizing symptom items loaded strongly on one factor (e.g., hurt another person = 0.703) whereas self-esteem and self-derogation internalizing symptom items loaded strongly on the other factor (e.g., not self-satisfied = 0.749). Uniqueness, capturing the item variance not shared with other items in the factor, ranged from 0.474 (“feel life isn’t very useful”) to 0.689 (“able to do things as well as others”) among internalizing symptoms in the two-factor solution. We selected the two-factor solution over the one-factor solution due to better fit (e.g., AIC for two-factor solution = 292,061 vs AIC for 1-factor solution = 808,345), and over the three-factor solution based on interpretability and parsimony (see Supplemental Table 2 for one- and three-factor solution statistics).

Average standardized internalizing and externalizing factor scores remained stable from 1991 to 2011 (Fig. 1). In 2012, trends in average factor scores diverged for internalizing and externalizing factors. The average standardized internalizing factor score increased from − 0.03 in 2012 to 0.06 in 2013 and the average externalizing factor score decreased from − 0.06 in 2011 to − 0.13 in 2012. The correlation between standardized internalizing and externalizing factor scores was 0.24 overall, remained relatively stable between 1991 to 2018, and was highest in 2007 (r = 0.28) and lowest in 1991 (r = 0.20) (Fig. 1).

While mean factor scores differed substantially among boys and girls, patterns over time were consistent by gender. Among both boys and girls, average standardized externalizing factor score decreased whereas average standardized internalizing factor score increased from 1991 to 2018. Among boys, the gap in average internalizing and externalizing factor scores narrowed over time until 2013–2014, when internalizing factor scores began to be higher than externalizing factor scores (e.g., + 0.14 average standardized internalizing factor score versus − 0.10 average standardized externalizing factor score in 2018). The gap between average standardized internalizing and externalizing factor scores remained narrow until 2010 among girls (+ 0.01 average standardized internalizing factor score versus − 0.15 average standardized externalizing factor score in 2010), then the gap between factor scores began to widen (+ 0.44 average standardized internalizing factor score versus − 0.21 average standardized externalizing factor score in 2018). The correlation between standardized internalizing and externalizing factor scores ranged from 0.22 in 1991 to 0.28 in 2016 among boys and ranged from 0.27 in 1991 to 0.33 in 2011 among girls from 1991 to 2018 (Fig. 1).

Examining time-varying associations between internalizing and externalizing factor scores showed that overall, the positive association was stable through the mid 2000s, though smaller in magnitude in the later 2000s and 2010s (Fig. 2). For every increase in standardized internalizing factor score, standardized externalizing factor score increased by 0.224 units in 2010 (95% CI: 0.215, 0.233). The increase in standardized externalizing factor score for each unit increase in standardized internalizing factor score was 22.3% smaller in 2018 compared with 2010 (beta coefficient in 2018: 0.174, 95% CI: 0.160, 0.188).

The magnitude of the time-varying association between internalizing and externalizing factor scores was lower in later years compared to earlier years among both boys and girls (Fig. 2). The association began decreasing among boys since approximately 1995. Among boys, for every increase in standardized internalizing factor score, standardized externalizing factor score increased by 0.327 units in 1995 (95% CI: 0.310, 0.344); this increase was 37.0% smaller in 2018 (i.e., 0.206 units; 95% CI: 0.181, 0.232). The association between factors began decreasing in magnitude among girls since 2010 after remaining stable from the mid 1990s to 2010. Among girls, for every increase in standardized internalizing factor score, standardized externalizing factor score increased by 0.203 units in 2010 (95% CI: 0.193, 0.213) and this increase was 24.6% lower by 2018 (i.e., 0.153 units; 95% CI: 0.138, 0.169).

Adolescents with high internalizing symptoms, both with and without high externalizing symptoms, are increasing in recent decades, especially in the 2010s, while those with high externalizing symptoms only are decreasing (Supplemental Fig. 1). Associations between demographic and substance use indicators and internalizing and externalizing symptom severity were strengthening in recent decades for high internalizing symptoms, both with and without high externalizing symptoms (Supplemental Table 3). Sensitivity analyses running the TVEM figure with externalizing factor score as the independent variable and internalizing factor score as the dependent variable showed results consistent with our main analyses.

Discussion

In a nationally representative study of 304,542 school-attending adolescents in the US, internalizing symptoms have increased substantially while externalizing symptoms have decreased since 2012. We found a two-factor structure of internalizing and externalizing symptoms that were consistently correlated between 1991 and 2018. When accounting for confounding factors, adjusted time-varying effect modification models indicated that the magnitude of the relationship between internalizing and externalizing symptoms decreased by 22.3% from 2010 to 2018. Recent decreases in the association suggest a potential weakening relationship between internalizing and externalizing symptoms over time. This could mean that the underlying mechanisms that led to an increase in adolescent internalizing symptoms and a decrease in externalizing symptoms in the 2010s are distinct.

Trends of increasing internalizing symptoms and decreasing externalizing symptoms are meaningful for public health in a variety of ways. Internalizing symptoms can be associated with negative social and health consequences both during adolescence and into adulthood [21]. This is of clinical importance because in a subset of adolescents internalizing symptoms can develop into psychiatric disorders [2], so clinicians should be aware of the raise in internalizing symptom prevalence among adolescents. Risk factors from multiple levels of organization influence internalizing symptoms, such as the individual-level (e.g., substance use comorbidity [47]), relationship-level (e.g., family conflict [48]), community-level (e.g., community violence [49]), and societal-level (e.g., access to social protections [50]). Thus, there are many areas to potentially intervene and address these increasing internalizing symptom trends among US adolescents in the past decade. For example, family-based interventions, such as the Familias Unidas intervention [51] and the Iowa Strengthening Families Program [52], school-based depression prevention programs that focus on interpersonal psychotherapy skills training [53], and resiliency programs utilizing cognitive-behavioral and problem-solving training [54] can mitigate severity of internalizing symptoms.

In addition to the overall trends observed there were gender-specific trends in the relationship between internalizing and externalizing symptoms. The magnitude of the relationship decreased by 37% among adolescent boys since 1995, well before the association decreased among girls starting in 2010. The stark increases in internalizing symptoms among girls since 2012 noted in prior literature [27, 40] could be due to a mechanism that has also caused the relationship between internalizing and externalizing symptoms to become weaker in girls during this time. The gender gap in the strength of the relationship between internalizing and externalizing symptoms appears to be narrowing over time until 2010, indicating that the same underlying mechanism could be driving the decrease in the association between internalizing and externalizing symptoms in both boys and girls.

These results could be used to generate hypotheses regarding predictors of the increase in internalizing symptoms, decrease in externalizing symptoms, and the potential weakening of the relationship between internalizing and externalizing symptoms at the population level. Various mechanisms have been proposed to explain rises in adolescent internalizing symptoms. For example, increases in time spent on social media [30] have been hypothesized to be a potential driver of increases in internalizing symptoms and subsequent disorders [30, 55]. However, empirical evidence has not supported the hypothesis that time spent on social media is a risk factor for internalizing symptoms [56, 57]. Another potential explanation for increasing internalizing symptom trends could be related to the overdose epidemic, as the third wave of the overdose epidemic that included increases in heroin overdoses starting in 2010 [58] coincided with the beginning of increases in internalizing symptoms observed in our study. There are many mechanisms through which the overdose epidemic might have contributed to increases in adolescent internalizing symptoms (e.g., stress and bereavement from family members suffering morbidity and/or mortality related to opioid use disorder), but this research remains underexplored. Additionally, rising family debt and economic recessions (e.g., the Great Recession) [59, 60] could also contribute to increases in internalizing symptoms from increased stress and pressure, but little research explores this relationship. Decreases in externalizing symptoms have been hypothesized to be related to increases in parental supervision and monitoring [61] or changes in how students spend their time (e.g., changes in unsupervised friend time, decreases in sexual activity and dating) [62,63,64], as adolescents might have fewer available environments for externalizing conduct symptoms to manifest.

Mechanisms for the potential weakening of the relationship between internalizing and externalizing symptoms observed in our study have not had similar focus in the literature. Increases in school surveillance and policing could plausibly increase adolescent internalizing symptoms due to heightened safety concerns and decrease conduct externalizing symptoms due to fewer opportunities to display these symptoms (e.g., vandalism), but this mechanism has not been thoroughly explored in the literature. The trends we observed are likely due to a combination of factors, as many explanations might explain the rise in internalizing or decrease in conduct externalizing symptoms alone but few plausible mechanisms explain both trends together. According to our supplemental analyses, the strength of associations between decade and various substance use measures and high internalizing and/or externalizing symptoms were greatest in the 2010s compared with earlier decades for adolescents with both high internalizing and externalizing symptoms versus low symptoms, suggesting that substance use could be contributing to increases in internalizing symptoms observed in our study. However, since protective effects were not found between recent decades, substance use measures, and the likelihood of high externalizing symptoms only versus low symptoms, changing substance use time trends are likely not contributing to the decreases in externalizing symptoms observed in our study. Research should continue to explore these and new potential mechanisms to explain trends in adolescent internalizing and externalizing symptoms, particularly mechanisms that do not yet have a strong evidence base (e.g., overdose epidemic, school surveillance).

We fit our model based on existing evidence that internalizing symptom onset generally precedes externalizing symptom onset [28, 29]. However, there can also be a bidirectional and reinforcing relationship between these two symptom dimensions. Externalizing problems among young people can predict internalizing symptoms later in the life course due to increased substance use [65, 66] or the undermining of academic [67, 68] or social competence [69] that are part of a developmental cascade extending into adulthood. Future longitudinal studies should assess the temporal ordering of symptoms to better understand the mechanisms contributing to potential diverging trends in adolescent internalizing and externalizing symptoms.

The increases in adolescent internalizing and decreases in externalizing symptoms observed in our study in school-attending United States adolescents have also been observed in other high-income countries, such as Sweden [70]. However, in the Netherlands both internalizing symptoms and externalizing conduct symptoms have been increasing in the past decade [71] but inconsistencies in these trends have been noted by prior researchers [71] as some studies found increases in internalizing symptoms [72] while other research observed stabilizing of both internalizing and externalizing conduct symptoms [73]. Further research should compare adolescent internalizing and externalizing trends across countries using standardized validated measurement tools and should seek to elucidate similarities and differences in mechanisms contributing to these trends.

Our findings also have implications for adolescent mental health screening and intervention. Many mental health disorders are initiated during developmental years, so it is important to identify and intervene early [74]. Many adolescents were identified as needing mental health services when exhibiting externalizing/conduct behaviors in schools [75]. For example, ADHD, could be under-diagnosed if adolescents are not displaying behavioral disruption and hyperactivity symptoms but rather present with more internalizing symptoms. ADHD is more commonly diagnosed in adolescents with hyperactivity, but there is an inattentive sub-type referred to as ADD that may be increasingly under-diagnosed [76]. Internalizing symptoms require specific active screening strategies to be detected as they are not disruptive and outwardly recognized. Our results suggest that we may need to re-shape how we identify mental health problems in schools. As externalizing symptoms are decreasing, relying on externalizing behavior reports to identify who needs mental health services could not capture the growing number of adolescents who are reporting higher internalizing symptoms. Since internalizing symptoms typically precede externalizing symptoms [28, 29], there may be an inaccurate perception that fewer adolescents need mental health services due to the decrease in externalizing/conduct behaviors over time. Adolescents may need more distinct tailored services, such as the MATCH transdiagnostic program allows one to tailor services for adolescents based on their symptomology [77]. Type of symptoms (i.e., internalizing and/or externalizing) can also influence response trajectories to specific interventions, such as interventions focused on trauma and grief [78].

Limitations

There are limitations in our study that are worth noting. In these cross-sectional data, we were unable to determine temporal order of internalizing and externalizing symptoms. We could not analyze certain internalizing symptom sub-domains that did not overlap with the externalizing symptom questionnaires during all years used in the analysis (e.g., loneliness, depressive affect). Internalizing symptom items in this survey captured more depressive and fewer anxious symptomatology, while externalizing symptom items captured more severe conduct symptoms and fewer milder symptoms (e.g., defiant behavior). MTF surveys did not address whether adolescents that had internalizing or externalizing symptoms received any treatment; however, according to a national analysis from 2005 to 2018 on average only 19.7% of adolescents received mental health treatment [79]. Race was not included in our analyses due to measurement variance and missing data. Sensitivity analyses explored additionally controlling for a crude measure of race (i.e., White, non-White) for those with race data available and results were consistent with the main findings. Gender was restricted to male and female adolescents, so we were unable to distinguish patterns among adolescents with other gender identities.

Conclusion

Amidst rapidly changing school and home environments in the last decade, internalizing symptoms have increased while externalizing symptoms have decreased among adolescents in the US. The strength of the relationship between internalizing and externalizing symptoms overall and by gender has changed over time, especially since 2010. Changes in trends in internalizing and externalizing symptoms have implications for adolescent mental health screening and treatment. Services may need to be tailored by symptom type and gender, as male and female adolescents may require distinct interventions for internalizing and/or externalizing symptoms. Future studies should assess causal drivers of the potential decoupling we observed between internalizing and externalizing symptom trends since 2010. Recently, the COVID-19 pandemic has changed school and home environments dramatically with many students attending school remotely [80, 81]. The resulting direct (e.g., loss of family and friends) and indirect (e.g., loss of household income due to a changing economic environment) stressors are likely to have a negative impact on adolescent mental health for years to come. In light the COVID-19 pandemic, understanding how to screen and provide services for adolescents is an important public health priority, so future studies should extend our analyses to assess how the pandemic may change the relationship between internalizing and externalizing symptoms.

Availability of data and material

Publicly available data can be downloaded here: https://www.icpsr.umich.edu/web/NAHDAP/series/35.

Code availability

Upon request.

Change history

04 April 2023

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-023-02467-3

References

Mathyssek CM, Olino TM, Verhulst FC, van Oort FV (2012) Childhood internalizing and externalizing problems predict the onset of clinical panic attacks over adolescence: the TRAILS study. PLoS ONE 7(12):e51564. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0051564

Nivard MG, Lubke GH, Dolan CV, Evans DM, St Pourcain B, Munafo MR, Middeldorp CM (2017) Joint developmental trajectories of internalizing and externalizing disorders between childhood and adolescence. Dev Psychopathol 29(3):919–928. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579416000572

Liu J (2004) Childhood externalizing behavior: theory and implications. J Child Adolesc Psychiatr Nurs 17(3):93–103. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6171.2004.tb00003.x

Graber J (2013) Internalizing problems during adolescence. In: Lerner RM, Steinberg L (eds) Handbook of adolescent psychology: lerner/adolescent psychology, 2nd edn. Wiley, Hoboken, pp 587–626. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780471726746.ch19

Cosgrove VE, Rhee SH, Gelhorn HL, Boeldt D, Corley RC, Ehringer MA, Young SE, Hewitt JK (2011) Structure and etiology of co-occurring internalizing and externalizing disorders in adolescents. J Abnorm Child Psychol 39(1):109–123. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-010-9444-8

Farrington D (2004) Conduct disorder, aggression, and delinquency. In: Lerner RM, Steinberg L (eds) Handbook of adolescent psychology. Wiley, Hoboken. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780471726746.ch20

Piqueras JA, Soto-Sanz V, Rodriguez-Marin J, Garcia-Oliva C (2019) What is the role of internalizing and externalizing symptoms in adolescent suicide behaviors? Int J Environ Res Public Health. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16142511

Vander Stoep A, Adrian M, McCauley E, Crowell SE, Stone A, Flynn C (2011) Risk for suicidal ideation and suicide attempts associated with co-occurring depression and conduct problems in early adolescence. Suicide Life Threat Behav 41(3):316–329. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1943-278X.2011.00031.x

Bhatia D, Mikulich-Gilbertson SK, Sakai JT (2020) Prescription opioid misuse and risky adolescent behavior. Pediatrics. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2019-2470

Hopfer C, Salomonsen-Sautel S, Mikulich-Gilbertson S, Min SJ, McQueen M, Crowley T, Young S, Corley R, Sakai J, Thurstone C, Hoffenberg A, Hartman C, Hewitt J (2013) Conduct disorder and initiation of substance use: a prospective longitudinal study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 52(5):511-518 e514. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2013.02.014

Singh GK, Kim IE, Girmay M, Perry C, Daus GP, Vedamuthu IP, De Los Reyes AA, Ramey CT, Martin EK, Allender M (2019) Opioid epidemic in the United States: empirical trends, and a literature review of social determinants and epidemiological, pain management, and treatment patterns. Int J MCH AIDS 8(2):89–100. https://doi.org/10.21106/ijma.284

Border R, Corley RP, Brown SA, Hewitt JK, Hopfer CJ, McWilliams SK, Rhea SA, Shriver CL, Stallings MC, Wall TL, Woodward KE, Rhee SH (2018) Independent predictors of mortality in adolescents ascertained for conduct disorder and substance use problems, their siblings and community controls. Addiction 113(11):2107–2115. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.14366

Cropsey KL, Weaver MF, Dupre MA (2008) Predictors of involvement in the juvenile justice system among psychiatric hospitalized adolescents. Addict Behav 33(7):942–948. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.02.012

Krueger R (1999) The structure of common mental disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry 56(10):921–926. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.56.10.921

Krueger RF, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Silva PA (1998) The structure and stability of common mental disorders (DSM-III-R): a longitudinal-epidemiological study. J Abnorm Psychol 107(2):216–227. https://doi.org/10.1037//0021-843x.107.2.216

Krueger RF, McGue M, Iacono WG (2001) The higher-order structure of common DSM mental disorders: internalization, externalization, and their connections to personality. Personal Individ Differ 30(7):1245–1259

Kessler RC, Ormel J, Petukhova M, McLaughlin KA, Green JG, Russo LJ, Stein DJ, Zaslavsky AM, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso J, Andrade L, Benjet C, de Girolamo G, de Graaf R, Demyttenaere K, Fayyad J, Haro JM, Hu C, Karam A, Lee S, Lepine JP, Matchsinger H, Mihaescu-Pintia C, Posada-Villa J, Sagar R, Ustun TB (2011) Development of lifetime comorbidity in the World Health Organization world mental health surveys. Arch Gen Psychiatry 68(1):90–100. https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.180

Achenbach TM (1966) The classification of children’s psychiatric symptoms: a factor-analytic study. Psychol Monogr 80(7):1–37. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0093906

Hinshaw SP (1987) On the distinction between attentional deficits/hyperactivity and conduct problems/aggression in child psychopathology. Psychol Bull 101(3):443–463

McElroy E, Shevlin M, Murphy J, McBride O (2018) Co-occurring internalizing and externalizing psychopathology in childhood and adolescence: a network approach. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 27(11):1449–1457. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-018-1128-x

Rapee RM, Oar EL, Johnco CJ, Forbes MK, Fardouly J, Magson NR, Richardson CE (2019) Adolescent development and risk for the onset of social-emotional disorders: a review and conceptual model. Behav Res Ther 123:103501. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2019.103501

Border R, Corley RP, Brown SA, Hewitt JK, Hopfer CJ, Stallings MC, Wall TL, Young SE, Rhee SH (2018) Predictors of adult outcomes in clinically- and legally-ascertained youth with externalizing problems. PLoS ONE 13(11):e0206442. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0206442

Cerda M, Sagdeo A, Galea S (2008) Comorbid forms of psychopathology: key patterns and future research directions. Epidemiol Rev 30:155–177. https://doi.org/10.1093/epirev/mxn003

Loeber R, Stouthamer-Loeber M, White HR (1999) Developmental aspects of delinquency and internalizing problems and their association with persistent juvenile substance use between ages 7 and 18. J Clin Child Psychol 28(3):322–332. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15374424jccp280304

Rohde P, Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR (1996) Psychiatric comorbidity with problematic alcohol use in high school students. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 35(1):101–109. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-199601000-00018

Costello EJ, Mustillo S, Erkanli A, Keeler G, Angold A (2003) Prevalence and development of psychiatric disorders in childhood and adolescence. Arch Gen Psychiatry 60(8):837–844. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.60.8.837

Mojtabai R, Olfson M, Han B (2016) National trends in the prevalence and treatment of depression in adolescents and young adults. Pediatrics. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-1878

Ialongo N, Edelsohn G, Werthamer-Larsson L, Crockett L, Kellam S (1996) The course of aggression in first-grade children with and without comorbid anxious symptoms. J Abnorm Child Psychol 24(4):445–456. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01441567

Ritakallio M, Koivisto AM, von der Pahlen B, Pelkonen M, Marttunen M, Kaltiala-Heino R (2008) Continuity, comorbidity and longitudinal associations between depression and antisocial behaviour in middle adolescence: a 2-year prospective follow-up study. J Adolesc 31(3):355–370. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2007.06.006

Twenge JM, Joiner TE, Rogers ML, Martin GN (2018) Increases in depressive symptoms, suicide-related outcomes, and suicide rates among US adolescents after 2010 and links to increased new media screen time. Clin Psychol Sci 6(1):3–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702617723376

Center for Disease Control (2018) Youth risk behavior survey–data summary and trends report: 2007–2017. https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/pdf/trendsreport.pdf. Accessed 17 June 2021

Keyes KM, Gary D, O’Malley PM, Hamilton A, Schulenberg J (2019) Recent increases in depressive symptoms among US adolescents: trends from 1991 to 2018. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 54(8):987–996. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-019-01697-8

Burstein B, Agostino H, Greenfield B (2019) Suicidal attempts and ideation among children and adolescents in US emergency departments, 2007–2015. JAMA Pediatr 173(6):598–600. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.0464

Keyes KM, Gary DS, Beardslee J, Prins SJ, O’Malley PM, Rutherford C, Schulenberg J (2018) Joint effects of age, period, and cohort on conduct problems among American adolescents from 1991 through 2015. Am J Epidemiol 187(3):548–557. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwx268

Miech RA, Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE, Patrick ME (2017) Monitoring the future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2016: volume I, secondary school students. Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan, Ann Arbor

Miech R, Johnston L, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Patrick ME (2019) Adolescent vaping and nicotine use in 2017–2018 US national estimates. N Engl J Med 380(2):192–193. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMc1814130

Miech R, Keyes KM, O’Malley PM, Johnston LD (2020) The great decline in adolescent cigarette smoking since 2000: consequences for drug use among US adolescents. Tob Control. https://doi.org/10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2019-055052

Moss SL, Santaella-Tenorio J, Mauro PM, Keyes KM, Martins SS (2019) Changes over time in marijuana use, deviant behavior and preference for risky behavior among US adolescents from 2002 to 2014: testing the moderating effect of gender and age. Addiction 114(4):674–686. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.14506

Achenbach TM, Ivanova MY, Rescorla LA, Turner LV, Althoff RR (2016) Internalizing/externalizing problems: Review and recommendations for clinical and research applications. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 55(8):647–656

Collishaw S (2015) Annual research review: secular trends in child and adolescent mental health. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 56(3):370–393. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12372

Curtin SC, Warner M, Hedegaard H (2016) Increase in suicide in the United States, 1999–2014. NCHS Data Brief 241:1–8

Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use: 1975-2017: Overview, key findings on adolescent drug use. Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan. http://monitoringthefuture.org/pubs/monographs/mtf-overview2017.pdf. Accessed 11 Nov 2021

Miech, Richard A., Johnston, Lloyd D., Bachman, Jerald G., O’Malley, Patrick M., and Schulenberg, John E. Monitoring the Future: A Continuing Study of American Youth (8th- and 10th-Grade Surveys), 2017. Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor], 2018-10-29. https://doi.org/10.3886/ICPSR37183.v1

Lanza ST, Vasilenko SA, Liu X, Li R, Piper ME (2014) Advancing the understanding of craving during smoking cessation attempts: a demonstration of the time-varying effect model. Nicotine Tob Res 16(Suppl 2):S127-134. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntt128

Tan X, Shiyko MP, Li R, Li Y, Dierker L (2012) A time-varying effect model for intensive longitudinal data. Psychol Methods 17(1):61–77. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025814

Li R, Dziak JJ, Tan X, Huang L, Wagner AT, Yang J (2017) TVEM (time-varying effect modeling) SAS macro users’ guide (Version 3.1.1). https://www.methodology.psu.edu/files/2019/03/TVEM_3.1.1-1fxcco8.pdf. Accessed 11 Nov 2021

Winstanley EL, Steinwachs DM, Stitzer ML, Fishman MJ (2012) Adolescent substance abuse and mental health: problem co-occurrence and access to services. J Child Adolesc Subst Abuse 21(4):310–322. https://doi.org/10.1080/1067828X.2012.709453

Herrenkohl TI, Kosterman R, Hawkins JD, Mason WA (2009) Effects of growth in family conflict in adolescence on adult depressive symptoms: mediating and moderating effects of stress and school bonding. J Adolesc Health 44(2):146–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.07.005

Copeland-Linder N, Lambert SF, Ialongo NS (2010) Community violence, protective factors, and adolescent mental health: a profile analysis. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 39(2):176–186. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374410903532601

Wickrama KAS, Bryant CM (2003) Community context of social resources and adolescent mental health. J Marriage Fam 65(4):850–866. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2003.00850.x

Brincks A, Perrino T, Howe G, Pantin H, Prado G, Huang S, Cruden G, Brown CH (2018) Preventing youth internalizing symptoms through the familias unidas intervention: examining variation in response. Prev Sci 19(Suppl 1):49–59. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-016-0666-z

Trudeau L, Spoth R, Randall GK, Mason WA, Shin C (2012) Internalizing symptoms: effects of a preventive intervention on developmental pathways from early adolescence to young adulthood. J Youth Adolesc 41(6):788–801. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-011-9735-6

Benas JS, McCarthy AE, Haimm CA, Huang M, Gallop R, Young JF (2019) The depression prevention initiative: impact on adolescent internalizing and externalizing symptoms in a randomized trial. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 48(sup1):S57–S71. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2016.1197839

Roberts C, Kane R, Thomson H, Bishop B, Hart B (2003) The prevention of depressive symptoms in rural school children: a randomized controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psychol 71(3):622–628. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006x.71.3.622

Barry CT, Sidoti CL, Briggs SM, Reiter SR, Lindsey RA (2017) Adolescent social media use and mental health from adolescent and parent perspectives. J Adolesc 61:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2017.08.005

Kreski N, Platt J, Rutherford C, Olfson M, Odgers C, Schulenberg J, Keyes KM (2021) Social media use and depressive symptoms among United States adolescents. J Adolesc Health 68(3):572–579. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.07.006

Vuorre M, Orben A, Przybylski AK (2021) There is no evidence that associations between adolescents’ digital technology engagement and mental health problems have increased. Clin Psychol Sci. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702621994549

Center for Disease Control (2021) Opioid overdose: understanding the epidemic. https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/epidemic/index.html. Accessed 17 June2021

Kim J, Chatterjee S (2019) Student loans, health, and life satisfaction of US households: evidence from a panel study. J Fam Econ Issues 40(1):36–50. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-018-9594-3

Golberstein E, Gonzales G, Meara E (2019) How do economic downturns affect the mental health of children? Evidence from the National Health Interview Survey. Health Econ 28(8):955–970. https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.3885

Borawski EA, Ievers-Landis CE, Lovegreen LD, Trapl ES (2003) Parental monitoring, negotiated unsupervised time, and parental trust: the role of perceived parenting practices in adolescent health risk behaviors. J Adolesc Health 33(2):60–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1054-139x(03)00100-9

Barnes GM, Hoffman JH, Welte JW, Farrell MP, Dintcheff BA (2007) Adolescents’ time use: Effects on substance use, delinquency and sexual activity. J Youth Adolesc 36:697–710. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-006-9075-0

Hoeve M, Stams GJ, van der Zouwen M, Vergeer M, Jurrius K, Asscher JJ (2014) A systematic review of financial debt in adolescents and young adults: prevalence, correlates and associations with crime. PLoS ONE 9(8):e104909. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0104909

Twenge JM, Park H (2019) The decline in adult activities among US adolescents, 1976–2016. Child Dev 90(2):638–654. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12930

Miettunen J, Murray GK, Jones PB, Maki P, Ebeling H, Taanila A, Joukamaa M, Savolainen J, Tormanen S, Jarvelin MR, Veijola J, Moilanen I (2014) Longitudinal associations between childhood and adulthood externalizing and internalizing psychopathology and adolescent substance use. Psychol Med 44(8):1727–1738. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291713002328

Cerda M, Prins SJ, Galea S, Howe CJ, Pardini D (2016) When psychopathology matters most: identifying sensitive periods when within-person changes in conduct, affective and anxiety problems are associated with male adolescent substance use. Addiction 111(5):924–935. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.13304

Masten AS, Roisman GI, Long JD, Burt KB, Obradovic J, Riley JR, Boelcke-Stennes K, Tellegen A (2005) Developmental cascades: linking academic achievement and externalizing and internalizing symptoms over 20 years. Dev Psychol 41(5):733–746. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.41.5.733

Moilanen KL, Shaw DS, Maxwell KL (2010) Developmental cascades: externalizing, internalizing, and academic competence from middle childhood to early adolescence. Dev Psychopathol 22(3):635–653. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579410000337

Obradovic J, Burt KB, Masten AS (2010) Testing a dual cascade model linking competence and symptoms over 20 years from childhood to adulthood. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 39(1):90–102. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374410903401120

Blomqvist I, Henje Blom E, Hagglof B, Hammarstrom A (2019) Increase of internalized mental health symptoms among adolescents during the last three decades. Eur J Public Health 29(5):925–931. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckz028

van Vuuren CL, Uitenbroek DG, van der Wal MF, Chinapaw MJM (2018) Sociodemographic differences in 10-year time trends of emotional and behavioural problems among adolescents attending secondary schools in Amsterdam, The Netherlands. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 27(12):1621–1631. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-018-1157-5

Bor W, Dean AJ, Najman J, Hayatbakhsh R (2014) Are child and adolescent mental health problems increasing in the 21st century? A systematic review. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 48(7):606–616. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867414533834

Duinhof EL, Stevens GW, van Dorsselaer S, Monshouwer K, Vollebergh WA (2015) Ten-year trends in adolescents’ self-reported emotional and behavioral problems in the Netherlands. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 24(9):1119–1128. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-014-0664-2

Center for Disease Control (2020) Data and statistics on children's mental health. https://www.cdc.gov/childrensmentalhealth/data.html. Accessed 29 July 2021

Cahill SM, Egan BE (2017) identifying youth with mental health conditions at school AOTA continuing education article 22 (5). https://www.aota.org/~/media/Corporate/Files/Publications/CE-Articles/CE-Article-March-2017.pd. Accessed 29 July 2021

Diamond A (2005) Attention-deficit disorder (attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder without hyperactivity): a neurobiologically and behaviorally distinct disorder from attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (with hyperactivity). Dev Psychopathol 17(3):807–825. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579405050388

Hersh J, Metz KL, Weisz JR (2016) New frontiers in transdiagnostic treatment: Youth psychotherapy for internalizing and externalizing problems and disorders. Int J Cogn Ther 9(2):140–155. https://doi.org/10.1521/ijct.2016.9.2.140

Herres J, Williamson AA, Kobak R, Layne CM, Kaplow JB, Saltzman WR, Pynoos RS (2017) Internalizing and externalizing symptoms moderate treatment response to school-based trauma and grief component therapy for adolescents. School Ment Health 9(2):184–193. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-016-9204-1

Mojtabai R, Olfson M (2020) National trends in mental health care for US adolescents. JAMA Psychiat. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.0279

Golberstein E, Wen H, Miller BF (2020) Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and Mental Health For Children And Adolescents. JAMA Pediatr. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.1456

Lee J (2020) Mental health effects of school closures during COVID-19. Lancet Child Adolesc Health 4(6):421. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30109-7

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (PI: Keyes, R01-DA048853, R49 CE002096) and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (PI: Mauro, K01DA045224).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MA conducted analyses, drafted the article, and revised the manuscript text. CR conducted data management/analyses and revised/ reviewed the manuscript. PM helped with interpretation of data and reviewed/revised the article critically for important intellectual content. NK helped conduct the literature review for the Introduction and Discussion sections of the text and reviewed/revised the manuscript. KK conceptualized and designed the study, helped with interpretation of data and reviewed/revised the article critically for important intellectual content.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

The Columbia University Institutional Review Board approved of this protocol.

Consent to participate

Monitoring the Future study participants all gave consent to participate.

Consent for publication

All authors have approved the manuscript for submission.

Additional information

The original online version of this article was revised: In this article the supplementary table 3 has been updated.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Askari, M.S., Rutherford, C.G., Mauro, P.M. et al. Structure and trends of externalizing and internalizing psychiatric symptoms and gender differences among adolescents in the US from 1991 to 2018. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 57, 737–748 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-021-02189-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-021-02189-4