Abstract

Background

The COVID-19 outbreak has made people more prone to depression, anxiety and insomnia, and females are at a high risk of developing these conditions. As a special group, pregnant and lying-in women must pay close attention to their physical and mental health, as both have consequences for the mother and the fetus. However, knowledge regarding the status of depression, anxiety and insomnia among these women is limited.

Aim

This study aimed to examine insomnia and psychological factors among pregnant and lying-in women during the COVID-19 pandemic and provide theoretical support for intervention research.

Methods

In total, 2235 pregnant and lying-in women from 12 provinces in China were surveyed; their average age was 30.25 years (SD = 3.99, range = 19–47 years).

Participants and setting

The participants completed electronic questionnaires designed to collect demographic information and assess levels of depression, anxiety and insomnia.

Results

The prevalence of insomnia in the sample was 18.9%. Depression and anxiety were significant predictors of insomnia. Participants in high-risk areas, those with a disease history, those with economic losses due to the outbreak, and those in the postpartum period had significantly higher insomnia scores.

Discussion

The incidence of insomnia among pregnant and lying-in women is not serious in the context of the epidemic, which may be related to the sociocultural background and current epidemic situation in China.

Conclusion

Depression and anxiety are more indicative of insomnia than demographic variables.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The COVID-19 outbreak began in late 2019, and the disease then spread worldwide. On January 30, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the outbreak of COVID-19 a global health emergency [1]. In the environment of high risk and stress caused by the outbreak of infectious diseases, people often feel fear and uncertainty and are prone to a series of psychological problems and somatic symptoms [2], such as insomnia [3].

Insomnia occurs when the quality and quantity of sleep are insufficient to meet a person’s physiological needs [4]. As a symptom, insomnia is a common experience in everyday life, but frequent insomnia constitutes a sleep disorder [5]. Long-term insomnia can lead to or aggravate other physical and mental diseases [6,7,8] and increase early mortality [9]. However, most insomnia is undiagnosed and untreated because general practitioners have minimal training in sleep issues and limited awareness of sleep disorders [10]. Studies have found that 60–64% of severe insomnia is not recognized by doctors during general clinical diagnosis and treatment and that 70% of chronic insomnia patients do not discuss their sleep problems with their doctor [11]. Given the negative effects of insomnia on physical health, psychological health, and social interaction, numerous researchers have studied the factors contributing to insomnia to attempt to better prevent this condition.

Insomnia is affected by many factors. As a sleep disorder, insomnia is often associated with many physiological factors. For example, disease causes [12] and the circadian rhythm [13] are often a concern among researchers. Additionally, the demographic factors associated with insomnia cannot be ignored. Previous studies have focused on the demographic factors affecting insomnia. The severity of insomnia gradually increases with age [14]. Moreover, the prevalence of insomnia is higher in people with lower education levels across different people with different levels of education [15]. In addition to its close link to physiology, insomnia has been variably associated with various other factors, including sociodemographic characteristics (e.g., age and education level) and psychological factors, such as compulsive behavior [16], depression [17] and anxiety [18]. Among the psychological problems that often accompany insomnia, the most common are depression and anxiety [19, 20]. Depression is characterized by a marked and persistent state of low mood or loss of interest or pleasure accompanied by a range of physical symptoms [21]. Sleep disturbance is one of the most common symptoms of depression. More than 70% of people with depression have insomnia [22]. Insomnia can be a short-term or long-term side effect of antidepressant treatment [23]. Similar to depression, anxiety has been strongly associated with insomnia in previous studies [18]. Anxiety is a symptom of excessive malaise, restlessness and distraction by events or internal thoughts and feelings [24]. A longitudinal study revealed that anxiety prospectively predicted insomnia [25]. In summary, previous studies have found that people with depression and anxiety are very likely to experience insomnia. The effects of depression and anxiety can exacerbate the symptoms of insomnia, protract the course of the disease, delay healing and even develop into chronic or long-term disease.

Female sex is a common risk factor for depression, anxiety and insomnia. Indeed, females are twice as likely as males to be diagnosed with insomnia due to menstruation and differences in hormonal levels according to a review of the literature [26]. Abundant evidence suggests that as a special group of females, pregnant and lying-in women are more likely to have depression, anxiety and insomnia, which could affect the physical and mental health of not only the mother but also the fetus. In addition, the physiological, hormonal and metabolic changes that occur during pregnancy tend to disrupt the mother’s sleep cycle [27,28,29,30]; thus, pregnancy is associated with insomnia [31]. In particular, under the current epidemic situation, as a vulnerable group, pregnant and lying-in women are more likely to be affected [32]. However, due to the need for regular antenatal care, these women often travel to high-risk areas, such as hospitals, increasing their chances of exposure to the virus. In addition, due to the shortage of medical resources during the epidemic, the medical services and support previously available to pregnant and lying-in women have become limited, and their psychological burden has increased. Moreover, because pregnancy-related sleep disorders are generally believed to be common and temporary in nature, few studies have investigated sleep disorders during pregnancy and postpartum [33]. Insomnia is overshadowed by other, more pressing disease problems during pregnancy and postpartum. Given the recessive nature of insomnia, identifying relatively more explicit psychological symptoms (such as depression and anxiety) may be more helpful in identifying and treating insomnia.

The purposes of this study were to investigate (1) differences in maternal insomnia scores by demographic factors under COVID-19 and (2) the predictive effects of demographic and psychological variables on insomnia.

Materials and methods

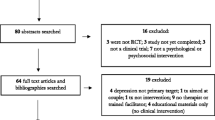

Participants

The data were derived from a survey conducted by the Institute of Psychology, Chinese Academy of Sciences to understand the physical and mental health of pregnant and lying-in women in China. In this study, 2237 questionnaires were recovered, and 2 invalid questionnaires were excluded (because the individuals had a serious addiction to smoking and drinking). The total number of valid questionnaires was 2235, and the mean age of the participants was 30.25 years (SD = 3.99, range = 19–47 years).

Procedures

This cross-sectional study was conducted in 12 provincial administrative regions of China from February 28 to April 26, 2020, and the participants were selected by convenience sampling. Obstetricians and gynecologists from various hospitals issued online questionnaires to pregnant and lying-in women who received antenatal care or gave childbirth through mobile phone links. The participants were informed that their participation was entirely voluntary and that their answers would be completely confidential. Prior to the completion of the online questionnaire, the participants signed written informed consent forms online. All procedures were approved by the Research Ethics Review Committee of the Institute of Psychology, Chinese Academy of Sciences.

Measures

The Chinese version of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale (GAD-7) was used to assess anxiety symptoms. The GAD-7 was developed by Spitzer et al. [34] and translated into Chinese [35]. The scale was used to measure how often the participants experienced anxiety symptoms in the past two weeks. This single-dimension scale includes seven items, and sample items are (a) being unable to stop or control worrying and (b) becoming easily annoyed or irritable. The scale items are scored from 0 (never) to 3 (almost every day). In this study, according to the cutoff scores [31], a score greater than or equal to 1 was defined as mild anxiety, a score greater than or equal to 5 was defined as moderate anxiety, a score greater than or equal to 10 was defined as moderate major anxiety, and a score greater than or equal to 15 was defined as major anxiety. This scale has high reliability and validity, and its Cronbach alpha coefficient is 0.92.

Depression symptoms were assessed using the Chinese version [36] of the nine-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) [37]. Sample items include (a) feeling tired or having little energy and (b) poor appetite or overeating. The questionnaire was used to investigate how often the participants experienced depressive symptoms in the last two weeks. The items ranged from 0 (not at all) to 3 (almost daily). According to the cutoff scores [37], a score greater than or equal to 5 was defined as mild depression, a score greater than or equal to 10 was defined as moderate depression, a score greater than or equal to 15 was defined as moderate major depression, and a score greater than or equal to 20 was defined as major depression. In this study, the questionnaire had high reliability and validity, and its Cronbach alpha coefficient was 0.86.

The insomnia severity index (ISI) was used to assess the severity of insomnia [38] and was translated and revised by Hong Kong researchers to create a Chinese version [39]. The scale was used to investigate the severity of insomnia in the last two weeks and obtain information regarding the impact of insomnia on health and daytime function. Sample items reflecting the severity of insomnia are (a) difficulty falling asleep; (b) difficulty staying asleep; and (c) problem waking up too early. The scale is composed of 7 items scored on a 5-point Likert scale from 0 (none) to 4 (extremely severe). The scoring guidelines were as follows: a score of 0–7 indicates insomnia without significant clinical manifestations; a score of 8–14 indicates mild insomnia; a score of 15–21 indicates moderate insomnia; and a score of 22–28 indicates major insomnia. This scale has high reliability and validity, and its Cronbach alpha coefficient is 0.93.

Considering that maternal demographic differences may exist among individuals, we also measured the following important demographic variables: whether living in a high-risk area, disease history, ethnicity, education level, annual household income, whether the outbreak caused economic losses, whether pregnant or postpartum, etc.

Analysis plan

IBM SPSS Statistics 25.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) was used for the data analysis. First, duplicate samples were eliminated by matching information, such as name, telephone number, and IP address. Then, the descriptive statistics of insomnia among the pregnant and lying-in women were calculated based on different levels of the demographic variables. T tests and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) were used to examine whether insomnia varied at multiple levels across the demographic variables. Finally, to determine whether depression, anxiety or demographic characteristics are risk factors for insomnia, we used insomnia as the dependent variable and depression score, anxiety score and demographic characteristics as the independent variables and conducted a binary logistic regression using the whole sample.

Results

Basic information regarding the insomnia severity index scores and demographic characteristics

The insomnia status of the sample by demographic characteristics was as follows: more than 1/3 of the participants were from a high-risk area, and the participants in high-risk areas had significantly higher levels of insomnia than those in non-high-risk areas. Among the sample, 14.3% of the participants were older pregnant women (≥ 35 years old), and there was no significant difference in insomnia between the older women and other women. Nearly 1/5 of the participants had a disease history, and the ISI score of the participants with a disease history was significantly higher than that of the participants without a disease history. Only approximately one-quarter of the participants did not experience economic losses due to the outbreak, and the ISI scores of the participants who had economic losses were significantly higher than that of those who did not have economic losses. There was no significant difference in the ISI scores between the pregnant and puerperal participants. However, in a detailed comparison of the first trimester, second trimester, third trimester and puerperal period, the results of the post hoc multiple comparisons revealed that the ISI scores in the puerperium period were significantly higher than those in the first trimester. More than half of the participants in the sample were in the perinatal period, and these participants scored significantly higher than the non-perinatal-period participants. Other specific information regarding the sample is shown in Table 1.

Effects of depression, anxiety and related demographic factors on insomnia

An ISI score greater than or equal to 8 points was considered indicative of different degrees of insomnia (N = 423). To further explore the association between the risk of insomnia and depression, anxiety and different demographic variables, we performed a binary logistic regression analysis using the entire sample.

After controlling for the demographic variables (i.e., educational level, annual household income, etc.), depression, anxiety and pregnancy were risk factors for insomnia. In particular, compared with the participants without depressive symptoms, those with mild depression, moderate depression, moderate major depression and major depression were 3.61 times (prevalence OR = 3.61, 95% CI: [2.68, 4.87]; p < 0.001), 7.2 times (prevalence OR = 7.20, 95% CI: [4.58, 11.31]; p < 0.001), 8.36 times (prevalence OR = 8.36, 95% CI: [4.22, 16.53]; p < 0.001) and 10.3 times (prevalence OR = 10.30, 95% CI: [2.92, 36.32]; p < 0.001) more likely to have insomnia, respectively. Compared with those without anxiety symptoms, those with mild anxiety, moderate anxiety, moderate major anxiety and major anxiety were 1.89 times (prevalence OR = 1.89, 95% CI: [1.36, 2.63]; p < 0.001), 3 times (prevalence OR = 3.00, 95% CI: [2.03, 4.43]; p < 0.001), 3.34 times (prevalence OR = 3.34, 95% CI: [1.69, 6.57]; p < 0.01) and 4.33 times (prevalence OR = 4.33, 95% CI: [1.38, 13.59]; p < 0.05) more likely to experience insomnia, respectively. In addition to depression and anxiety, the different pregnancy periods statistically significantly predicted insomnia. Those in the second trimester were more likely to have insomnia than were those in the first trimester. Other details are shown in Table 2.

Discussion

The present study investigated the insomnia status and related factors of pregnant Chinese women under the current COVID-19 outbreak. The overall insomnia status of the pregnant and lying-in women in the context of the epidemic was not serious. Compared with the demographic variables, depression and anxiety had a more significant predictive effect on insomnia.

Prevalence of insomnia among pregnant and lying-in women

In our study, the prevalence of maternal insomnia was 18.9%, which is lower than that in Western reports [40, 41] and comparable to the results of Chinese participants [42].

The insomnia prevalence in this study was not serious possibly because the epidemic in China was under control during the data collection period. Although the epidemic is worsening in other countries, the situation in China is improving, and sufficient medical facilities and materials, adequate medical support and comprehensive personal protection are available. Therefore, the participants were less worried about the epidemic and felt more secure. In addition, cultural differences may be responsible for the lower prevalence in this study than in previous Western studies. Previous studies have shown that cultural factors play an important role in insomnia [43, 44] and that traditional Chinese culture, which is a culture of diligence that is publicly encouraged, may minimize sleep problems. In such a social and cultural context, people may think that long periods of sleep are a sign of laziness [45]. Therefore, the participants in this study may report a low incidence of insomnia because they believe that insomnia is not a sleep problem.

Insomnia differences by demographic factors among pregnant and lying-in women

In this study, the sample was grouped according to the demographic variables, and the differences in the insomnia scores between the groups were studied. Specifically, we observed that the insomnia scores of the pregnant and lying-in women in high-risk areas were significantly higher than those of women in non-high-risk areas, which is consistent with the results of previous studies. Excessive worry and fear of infection can lead to higher levels of insomnia among people in high-risk areas for infection [46]. Age-based differences were not obvious in this study likely because, in this study, the overall size of the older female group was relatively small, leading to low statistical power. Furthermore, compared with the Han ethnic participants and the participants with a high household income, the ethnic minority participants and the participants with a relatively low household income had higher insomnia scores, respectively, which is consistent with previous studies [47, 48]. In the broader literature concerning sleep problems in adults, studies have found that marginalized populations are more likely to have sleep problems and disorders. For example, in the U.S., low-income and economically disadvantaged participants [49] and minority participants [50] have a higher prevalence of sleep disorders, and emerging evidence suggests that these differences also exist in the maternal population [51] likely because insomnia is closely related to the economic and life pressures associated with poverty [52].

The maternal insomnia score in this study significantly increased as childbirth approached and reached the highest value after childbirth, which is consistent with previous research results [53]. During each pregnancy and postpartum period, previous studies have shown that the self-reported total sleep duration was slightly increased during the first trimester [54] and the lowest at 1 month postpartum [55]. Furthermore, the number and duration of night-time awakenings increase as childbirth approaches [56]. In addition, pregnant women may have difficulty falling asleep [57] and may wake up too early [58]. Women sleep poorly during pregnancy and less during the postpartum period [59]. In the third trimester of pregnancy, the increasing fetal size leads to an increase in the frequency of sleeping position discomfort and restless legs, which are major causes of insomnia in the third trimester of pregnancy [60, 61].

Predictive effects of depression and anxiety on insomnia

This study found a high positive correlation between insomnia and depression [62, 63], and insomnia and anxiety were closely and positively related [24]. The correlation between depression and insomnia has been demonstrated in previous studies [29]. As a form of emotional distress, depression is closely related to insomnia [64] , which is especially evident in pregnant women [65], and the positive predictive effect of depression on insomnia may be due to their common genetic components. A comorbidity model may more precisely explain the relationship between insomnia and depression [66]. Similar to depression, as a negative emotional response, anxiety is significantly associated with insomnia, and these negative emotional responses are the main reason for the long-term persistence of insomnia symptoms. According to cognitive models of insomnia, people with insomnia often worry excessively about their sleep and the consequences of sleep deprivation. This extreme state of anxiety triggers selective attention and the monitoring of internal and external sleep-related threat cues [67, 68]. The positive predictive effect of anxiety on insomnia may be due to a hyperactive arousal system, which is a common cause of individual insomnia and anxiety [69, 70. In summary, depression and anxiety are closely related to insomnia, and genetic factors play a modest role in the etiology of insomnia symptoms and overlap with the genetics of depression and anxiety disorder [71].

Limitations

The study had several limitations. First, we used self-assessment questionnaires to measure levels of depression, anxiety and insomnia. Although the use of self-assessment questionnaires to measure variables is common [72, 73], self-assessment can lead to measurement inaccuracies. Our investigation provides a preliminary discussion of insomnia in pregnant women under the epidemic situation and cannot be used for clinical diagnosis. In future studies, more objective insomnia assessment tools, such as sleep observation instruments, should be adopted. Second, other factors, such as posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms [74], that were not measured may influence the level of insomnia. In addition, this study is a cross-sectional study, and we cannot determine the direction or causality of the associations based on our data. In the future, it is necessary to strengthen longitudinal research investigating the maternal physical and mental health status and carry out long-term follow-up.

This study has important practical significance. First, the negative effects of living in a high-risk area on participants' insomnia cannot be ignored. Although the present epidemic situation in China is positive overall and maternal insomnia is not serious, we found that women in high-risk areas still had significantly higher rates of insomnia than women in non-high-risk areas. Thus, insomnia screening and intervention in high-risk areas are urgently needed. Second, research concerning maternal insomnia can help remind pregnant and lying-in women and all sectors of society to pay attention to maternal sleep conditions to improve their sleep quality and further have more positive effects on the current and future development of children by improving the sleep problems of mothers. Finally, this study found psychological variables to be more significant predictors of insomnia than demographic variables; thus, sleep interventions should focus on whether women have depression, anxiety or other key factors that affect insomnia.

References

World Health Organization (2020) Statement on the second meeting of the International Health Regulations Emergency Committee Regarding the Outbreak of Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV). https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/30-01-2020-statement-on-the-second-meeting-of-the-international-health-regulations-(2005)-emergency-committee-regarding-the-outbreak-of-novel-coronavirus-(2019-ncov) Accessed 23 Aug 2020

Kim U, Joanne D, Navjot B (2020) The covid-19 pandemic and mental health impacts. Int J Ment Health Nurs 29:315–318

Xiang Y, Yang Y, Li W et al (2020) Timely mental health care for the 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak is urgently needed. Lancet Psychiatry 7:228–229

National Institutes of Health (2005) National institutes of health state of the science conference statement on manifestations and management of chronic insomnia in adults, June 13-15, 2005. Sleep 28:1049–1057

Mai E, Buysse DJ (2008) Insomnia: prevalence, impact, pathogenesis, differential diagnosis, and evaluation. Sleep Med Clin 3:167–174

Schwartz S, Anderson WM, Stephen RC, Huntley JC, Hays JC, Blazer D (1999) Insomnia and heart disease:a review of epidemiologic studies. J Psychosom Res 47:313–333

Machi S, Katsumi Y, Hiroki S (2003) Persistent insomnia is a predictor of hypertension in Japanese male workers. J Occup Health 45:344–350

Burgos I, Richter L, Klein T et al (2006) Increased nocturnal interleukin-6 excretion in patients with primary insomnia: a pilot study. Brain Behav Immun 20:246–253

Janson C, Lindberg E, Gislason T, Elmasry A, Boman G (2001) Insomnia in men-a 10-year prospective population based study. Sleep 24:425–430

Rosen RC, Mark R, Rosevear C, Cole WE, Dement WC (1993) Physician education in sleep and sleep disorders: a national survey of U.S. medical schools. Sleep 3:249–254

Schramm E, Hohagen F, Käppler C, Grasshoff U, Berger M (1995) Mental comorbidity of chronic insomnia in general practice attenders using dsm-iii-r. Acta Psychiatr Scand 91:10–17

Taylor DJ, Mallory LJ, Lichstein KL, Durrence HH, Riedel BW, Bush AJ (2007) Comorbidity of chronic insomnia with medical problems. Sleep 30:213–218

Rogers AE (2002) Sleep deprivation and the ed night shift. J Emerg Nurs 28:469–470

Yen C, King BH, Chang Y (2002) Factor structure of the Athens Insomnia Scale and its associations with demographic characteristics and depression in adolescents. J Sleep Res 19:12–18

Kim WJ, Joo WT, Baek J, Sohn SY, Lee E (2017) Factors associated with insomnia among the elderly in a korean rural community. Psychiatry Investig 14:400–406

Li S, Kong J (2017) Review on the functional mechanism of obsessive-compulsive disorder which leads to insomnia. World J Sleep Med 4:401–404

Li SX, Lam SP, Chan JWY, Yu MWM, Wing YK (2012) Residual sleep disturbances in patients remitted from major depressive disorder: a 4-year naturalistic follow-up study. Sleep 35:1153–1161

Ohayon MM, Roth T (2003) Place of chronic insomnia in the course of depressive and anxiety disorders. J Psychiatr Res 37:9–15

Stepanski EJ, Rybarczyk B (2006) Emerging research on the treatment and etiology of secondary or comorbid insomnia. Sleep Med Rev 10:7–18

Turek FW (2005) Insomnia and depression: if it looks and walks like a duck. Sleep 28:1362

American Psychiatric Association (1994) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th edn) Washington, DC

Lu Z (2013) Treatment of depression associated with sleep disorder. Chin J Psychiatry 46:179–180

Fava M (2004) Daytime sleepiness and insomnia as correlates of depression. J Clin Psychiatry 65(Suppl 16):27–32

Osnes RS, Roaldset JO, Follestad T, Eberhard-Gran M (2019) Insomnia late in pregnancy is associated with perinatal anxiety: a longitudinal cohort study. J Affect Disord 248:155–165

Bar M, Schrieber G, Gueron-Sela N, Shahar G, Tikotzky L (2020) Role of self-criticism, anxiety, and depressive symptoms in young adults’ insomnia. Int J Cogn Ther 13:15–29

Sharma S, Franco R (2004) Sleep and its disorders in pregnancy. Wis Med J 103:48–52

Maurice MO (2002) Epidemiology of insomnia: what we know and what we still need to learn. Sleep Med Rev 6:97–111

Okun ML, Hanusa BH, Hall M, Wisner JL (2009) Sleep complaints in late pregnancy and the recurrence of postpartum depression. Behav Sleep Med 7:106–117

Okun ML, Kiewra K, Luther JF, Wisniewski SR, Wisner KL (2011) Sleep disturbances in depressed and nondepressed pregnant women. Depress Anxiety 28:676–685

Okun ML, Roberts JM, Marsland AL, Hall M (2009) How disturbed sleep may be a risk factor for adverse pregnancy outcomes. Obstet Gynecol Surv 64:273–280

Teran-Perez G, Arana-Lechuga Y, Esqueda-Leon E, Santana-Miranda R, Rojas-Zamorano JA, Velazqyuez MJ (2012) Steroid hormones and sleep regulation. Mini Rev Med Chem 12:1040–1048

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2020) Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): people who are at higher risk for severe illness. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/specific-groups/highrisk-complications.html. Accessed 23 Aug 2020

Polo-Kantola P, Aukia L, Karlsson H, Karlsson L, Paavonen EJ (2017) Sleep quality during pregnancy: associations with depressive and anxiety symptoms. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 96:198–206

Spitzer RL, Kroenhe K, Williams JBW, Bernd L (2006) A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder. Arch Intern Med 166:1092–1097

He X, Li C, Qian J, Cui H, Wu W (2010) Reliability and validity of a generalized anxiety disorder scale in general hospital outpatients, Shanghai. Arch Psychiatry 4:12–15

Bian C, He X, Qian J, Wu W, Li C (2009) The reliability and validity of a modified patient health questionnaire for screening depressive syndrome in general hospital outpatients. J Tongji Univ (Med Sci) 30:136–140

Spitzer RL, Kroenhe K, Williams JBW (1999) Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD the PHQ primary care study. JAMA J Am Med Assoc 282:1737–1744

Morin CM (1993) Insomnia: psychological assessment and management. The Guilford Press, New York

Yu DSF (2010) Insomnia severity index: psychometric properties with chinese community-dwelling older people. J Adv Nurs 66:2350–2359

Babaie NA, Purhashemi S (2016) Investigating the relationship between mental health and insomnia in pregnant women referred to health centers in estahban. Makara J Health Res 19:87–91

Voitsidis P, Gliatas I, Bairachtari V, Papadopoulou K, Papageorgiou G (2020) Insomnia during the covid-19 pandemic in a greek population. Psychiat Res. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113076

Wang W, Hou C, Jiang Y et al (2020) Prevalence and associated risk factors of insomnia among pregnant women in China. Compr Psychiatry 98:152168

Gureje O, Makanjuola VA, Kola L (2007) Insomnia and role impairment in the community: results from the Nigerian survey of mental health and wellbeing. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 42:495–501

Ohayon MM, Partinen M (2002) Insomnia and global sleep dissatisfaction in Finland. J Sleep Res 11:339–346

Pan FY (2003) Confucian culture and modernization in China. J Hubei Norm Univ 23:64–66

Usher K, Durkin J, Bhullar N (2020) The covid-19 pandemic and mental health impacts. Int J Ment Health Nurs 29:315–318

Grandner MA, Patel NP, Gehrman PR (2009) Who gets the best sleep? Ethnic and socioeconomic factors related to sleep complaints. Sleep Med 11:470–478

Stamatakis KA, Kaplan GA, Roberts RE (2007) Short sleep duration across income, education, and race/ethnic groups: population prevalence and growing disparities during 34 years of follow-up. Ann Epidemiol 17:948–955

Hall MH, Matthews KA, Kravitz HM (2009) Race and financial strain are independent correlates of sleep in midlife women: the SWAN sleep study. Sleep 32:73–82

Kalmbach DA, Pillai V, Arnedt JT, Drake CL (2016) DSM-5 insomnia and short sleep: comorbidity landscape and racial disparities. Sleep 39:2101–2111

Mindell JA, Cook RA, Nikolovski J (2015) Sleep patterns and sleep disturbances across pregnancy. Sleep Med 16:483–488

Patel NP, Grandner MA, Xie D, Branas CC, Gooneratne N (2010) ”Sleep disparity” in the population: poor sleep quality is strongly associated with poverty and ethnicity. BMC Public Health 10:475

Kızılırmak A, Timur S, Kartal B (2012) Insomnia in pregnancy and factors related to insomnia. Sci World J. https://doi.org/10.1100/2012/197093

Lee KA, McEnany G, Zaffke ME (2000) REM sleep and mood state in childbearing women: sleepy or weepy? Sleep 23:877–885

Hedman C, Pohjasvaara T, Tolonen U, Suhonen-Malm AS, Myllyla VV (2002) Effects of pregnancy on mothers’ sleep. Sleep Med 3:37–42

Mindell JA, Ann R, Nikolovski J (2015) Sleep patterns and sleep disturbances across pregnancy. Sleep Med 16:483–488

Neau J, Texier B, Ingrand P (2009) Sleep and vigilance disorders in pregnancy. Eur Neurol 62:23–29

Mindell J, Jacobson BJ (2000) Sleep disturbances during pregnancy. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 29:590–597

Dorheim SK, Bjorvatn B, Eberhard-Gran M (2012) Insomnia and depressive symptoms in late pregnancy: a population-based study. Behav Sleep Med 10:152–166

Lee KA, Zaffke ME, Baratte-Beebe K (2001) Restless legs syndrome and sleep disturbance during pregnancy: the role of folate and iron. J Womens Health Gender Based Med 10:335–341

Uglane MT, Wested S, Backe B (2011) Restless legs syndrome in pregnancy is a frequent disorder with a good prognosis. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 90:1046–1048

Kamysheva E, Skouteris H, Wertheim EH, Paxton SJ, Milgrom J (2010) A prospective investigation of the relationships among sleep quality, physical symptoms, and depressive symptoms during pregnancy. J Affect Disord 123:317–320

Field T, Diego M, Hernandez-Reif M, Figueiredo B, Schanberg S, Kuhn C (2007) Sleep disturbances in depressed pregnant women and their newborns. Infant Behav Dev 30:127–133

Meredith ER, Kaitlin HW, Rush MB (2015) Sleep disturbances in mood disorders. Psychiatr Clin North Am 38:743–759

Skouteris H, Germano C, Wertheim EH, Paxton SJ, Milgrom J (2008) Sleep quality and depression during pregnancy: a prospective study. J Sleep Res 17:217–220

Zhang J, Lam SP, Wing YK (2012) Longitudinal studies of insomnia: current state and future challenges. Sleep Med 13:1113–1114

Harvey AG (2002) A cognitive model of insomnia. Behav Res Ther 40:869–893

Azevedo H, Bos S, Pereira AT et al (2008) Psychological distress in pregnant women with insomnia. Sleep 31:A746

Riemann D, Nissen C, Palagini L, Otte A, Perlis ML, Spiegelhalder K (2015) The neurobiology, investigation, and treatment of chronic insomnia. Lancet Neurol 14:547–558

Riemann D, Spiegelhalder K, Feige B et al (2010) The hyperarousal model of insomnia: a review of the concept and its evidence. Sleep Med Rev 14:19–31

Gehrman PR, Meltzer LJ, Moore M et al (2011) Heritability of insomnia symptoms in youth and their relationship to depression and anxiety. Sleep 34:1641–1645

Liu X, Tang M (1996) Reliability and validity of the Pittsburgh sleep quality index. Chin J Psychiatry 29:103–107

Chen N, Johns MW, Li H et al (2002) Validation of a chinese version of the epworth sleepiness scale. Qual Life Res 11:817–821

Mazzotta CM, Crean HF, Pigeon WR, Cerulli C (2018) Insomnia, posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms, and danger: their impact on victims’ return to court for orders of protection. J Interpers Violence. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260518766565

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants and the research assistants at the hospitals.

Funding

Funding for this study was provided by the National Key R&D Program of China (2020YFC2003000) and Shenzhen-Hong Kong Institute of Brain Science—Shenzhen Fundamental Research Institutions (NYKFKT2020002).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, JW, RH and ZL; Writing—original draft preparation, JW and YZ; investigation, WQ; supervision, YZ.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest and that there was no significant financial support for this work that could have influenced its outcome. The funders had no role in the study design, collection, analysis or interpretation of the data, the writing of the manuscript, or the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Ethical statement

All procedures were approved by the Research Ethics Review Committee of the Institute of Psychology, Chinese Academy of Sciences.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, J., Zhou, Y., Qian, W. et al. Maternal insomnia during the COVID-19 pandemic: associations with depression and anxiety. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 56, 1477–1485 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-021-02072-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-021-02072-2