Abstract

Purpose

This systematic review aims to synthesise the evidence on behavioural and attitudinal patterns as well as barriers and enablers in Filipino formal help-seeking.

Methods

Using PRISMA framework, 15 studies conducted in 7 countries on Filipino help-seeking were appraised through narrative synthesis.

Results

Filipinos across the world have general reluctance and unfavourable attitude towards formal help-seeking despite high rates of psychological distress. They prefer seeking help from close family and friends. Barriers cited by Filipinos living in the Philippines include financial constraints and inaccessibility of services, whereas overseas Filipinos were hampered by immigration status, lack of health insurance, language difficulty, experience of discrimination and lack of acculturation to host culture. Both groups were hindered by self and social stigma attached to mental disorder, and by concern for loss of face, sense of shame, and adherence to Asian values of conformity to norms where mental illness is considered unacceptable. Filipinos are also prevented from seeking help by their sense of resilience and self-reliance, but this is explored only in qualitative studies. They utilize special mental health care only as the last resort or when problems become severe. Other prominent facilitators include perception of distress, influence of social support, financial capacity and previous positive experience in formal help.

Conclusion

We confirmed the low utilization of mental health services among Filipinos regardless of their locations, with mental health stigma as primary barrier, while resilience and self-reliance as coping strategies were cited in qualitative studies. Social support and problem severity were cited as prominent facilitators.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Mental illness is the third most common disability in the Philippines. Around 6 million Filipinos are estimated to live with depression and/or anxiety, making the Philippines the country with the third highest rate of mental health problems in the Western Pacific Region [1]. Suicide rates are pegged at 3.2 per 100,000 population with numbers possibly higher due to underreporting or misclassification of suicide cases as ‘undetermined deaths’ [2]. Despite these figures, government spending on mental health is at 0.22% of total health expenditures with a lack of health professionals working in the mental health sector [1, 3]. Elevated mental health problems also characterise ‘overseas Filipinos’, that is, Filipinos living abroad [4]. Indeed, 12% of Filipinos living in the US suffer from psychological distress [5], higher than the US prevalence rate of depression and anxiety [1]. Long periods of separation from their families and a different cultural background may make them more prone to acculturative stress, depression, anxiety, substance use and trauma especially those who are exposed to abuse, violence and discrimination whilst abroad [6].

One crucial barrier to achieving well-being and improved mental health among both ‘local’ and overseas Filipinos is their propensity to not seek psychological help [7, 8]. Not only are help-seeking rates much lower than rates found in general US populations [9], they are also low compared to other minority Asian groups [10]. Yet, few studies have been published on Filipino psychological help-seeking either in the Philippines or among those overseas [11]. Most available studies have focused on such factors as stigma tolerance, loss of face and acculturation factors [12, 13].

To date, no systematic review of studies on Filipino psychological help-seeking, both living in the Philippines and overseas, has been conducted. In 2014, Tuliao conducted a narrative review of the literature on Filipino mental health help-seeking in the US which provided a comprehensive treatise on cultural context of Filipino help-seeking behavior [11]. However, new studies have been published since which examine help-seeking in other country contexts, such as Norway, Iceland, Israel and Canada [6, 14,15,16]. Alongside recent studies on local Filipinos, these new studies can provide basis for comparison of the local and overseas Filipinos [7, 8, 12, 17].

This systematic review aims to critically appraise the evidence on behavioural and attitudinal patterns of psychological help-seeking among Filipinos in the Philippines and abroad and examine barriers and enablers of their help-seeking. While the majority of studies undertaken have been among Filipino migrants especially in the US where they needed to handle additional immigration challenges, studying help-seeking attitudes and behaviours of local Filipinos is important as this may inform those living abroad [10, 13, 18]. This review aims to: (1) examine the commonly reported help-seeking attitudes and behaviors among local and overseas Filipinos with mental health problems; and (2) expound on the most commonly reported barriers and facilitators that influence their help-seeking.

Methods

The review aims to synthesize available data on formal help-seeking behavior and attitudes of local and overseas Filipinos for their mental health problems, as well as commonly reported barriers and facilitators. Formal psychological help-seeking behavior is defined as seeking services and treatment, such as psychotherapy, counseling, information and advice, from trained and recognized mental health care providers [19]. Attitudes on psychological help-seeking refer to the evaluative beliefs in seeking help from these professional sources [20].

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria for the studies were the following: (1) those that address either formal help-seeking behavior OR attitude related to a mental health AND those that discuss barriers OR facilitators of psychological help-seeking; (2) those that involve Filipino participants, or of Filipino descent; in studies that involve multi-cultural or multi-ethnic groups, they must have at least 20% Filipino participants with disaggregated data on Filipino psychological help-seeking; (3) those that employed any type of study designs, whether quantitative, qualitative or mixed-methods; (4) must be full-text peer-reviewed articles published in scholarly journals or book chapters, with no publication date restrictions; (5) written either in English or Filipino; and (6) available in printed or downloadable format. Multiple articles based on the same research are treated as one study/paper.

Exclusion criteria were: (1) studies in which the reported problems that prompted help-seeking are medical (e.g. cancer), career or vocational (e.g., career choice), academic (e.g., school difficulties) or developmental disorders (e.g., autism), unless specified that there is an associated mental health concern (e.g., anxiety, depression, trauma); (2) studies that discuss general health-seeking behaviors; (3) studies that are not from the perspective of mental health service users (e.g., counselor’s perspective); (4) systematic reviews, meta-analyses and other forms of literature review; and (5) unpublished studies including dissertations and theses, clinical reports, theory or methods papers, commentaries or editorials.

Search strategy and study selection

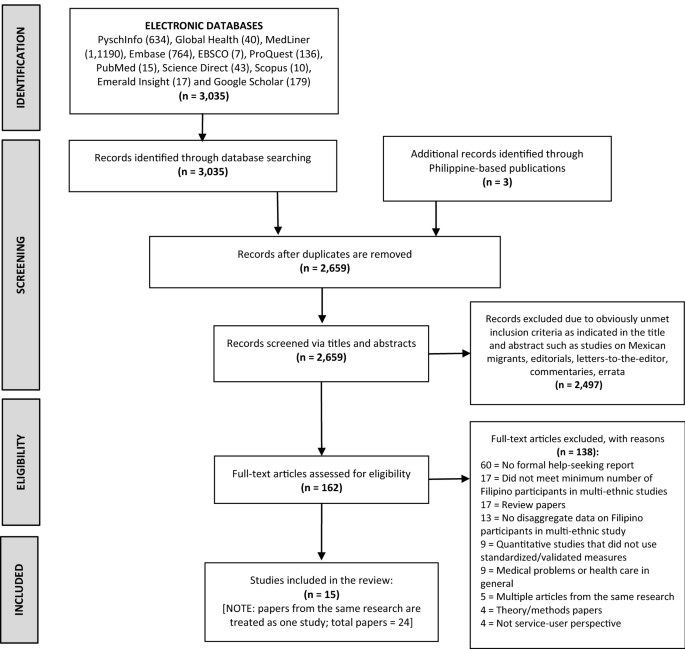

The search for relevant studies was conducted through electronic database searching, hand-searching and web-based searching. Ten bibliographic databases were searched in August to September 2018: PsychInfo, Global Health, MedLine, Embase, EBSCO, ProQuest, PubMed, Science Direct, Scopus and Emerald Insight. The following search terms were used: “help-seeking behavior” OR “utilization of mental health services” OR “access to mental health services” OR “psychological help-seeking” AND “barriers to help-seeking” OR “facilitators of help-seeking” AND “mental health” OR “mental health problem” OR “mental disorder” OR “mental illness” OR “psychological distress” OR “emotional problem” AND “Filipino” OR “Philippines”. Filters were used to select only publications from peer-reviewed journals. Internet searches through Google Scholar and websites of Philippine-based publications were also performed using the search term “Filipino mental health help-seeking” as well as hand-searching of reference lists of relevant studies. A total of 3038 records were obtained. Duplicates were removed and a total of 2659 records were screened for their relevance based on their titles and abstracts.

Preliminary screening of titles and abstracts of articles resulted in 162 potentially relevant studies, their full-text papers were obtained and were reviewed for eligibility by two reviewers (AM and MC). Divergent opinions on the results of eligibility screening were deliberated and any further disagreement was resolved by the third reviewer (JB). A total of 15 relevant studies (from 24 papers) published in English were included in the review and assessed for quality. There were seven studies with multiple publications (two of them have 3 papers) and a core paper was chosen on the basis of having more comprehensive key study data on formal help-seeking. Results of the literature search are reported in Fig. 1 using the PRISMA diagram [21]. A protocol for this review was registered at PROSPERO Registry of the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination of the University of York (https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO; ID: CRD42018102836).

Data extraction and quality assessment

Data extracted by the main author were crosschecked by a second reviewer (JB). A data extraction table with thematic headings was prepared and pilot tested for two quantitative and two qualitative studies to check data comparability. Extraction was performed using the following descriptive data: (1) study information (e.g. name of authors, publication date, study location, setting, study design, measurement tools used); (2) socio-demographic characteristics of participants (e.g. sample size, age, gender); and (3) overarching themes on psychological help-seeking behavior and attitudes, as well as barriers and facilitators of help-seeking.

Two reviewers (AM and MC) did quality assessment of the studies separately, using the following criteria: (1) relevance to the research question; (2) transparency of the methods; (3) robustness of the evidence presented; and (4) soundness of the data interpretation and analysis. Design-specific quality assessment tools were used in the evaluation of risk of bias of the studies, namely: (1) Critical Appraisal Skills Programme Qualitative Checklist [22]; and (2) Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies by the Effective Public Health Practice Project [23]. The appraisals for mixed-methods studies were done separately for quantitative and qualitative components to ensure trustworthiness [24] of the quality of each assessment.

For studies reported in multiple publications, quality assessment was done only on the core papers [25]. All the papers (n = 6) assessed for their qualitative study design (including the 4 mixed-methods studies) met the minimum quality assessment criteria of fair (n = 1) and good (n = 5) and were, thus, included in the review. Only 11 out of the 13 quantitative studies (including the 4 mixed-methods studies) satisfied the minimum ratings for the review, with five getting strong quality rating. The two mixed-methods studies that did not meet the minimum quality rating for quantitative designs were excluded as sources of quantitative data but were used in the qualitative data analysis because they satisfied the minimum quality rating for qualitative designs.

Strategy for data analysis

Due to the substantial heterogeneity of the studies in terms of participant characteristics, study design, measurement tools used and reporting methods of the key findings, narrative synthesis approach was used in data analysis to interpret and integrate the quantitative and qualitative evidence [26, 27]. However, one crucial methodological limitation of studies in this review is the lack of agreement on what constitutes formal help-seeking. Some researchers include the utilization of traditional or indigenous healers as formal help-seeking, while others limit the concept to professional health care providers. As such, consistent with Rickwood and Thomas’ definition of formal help-seeking [19], data extraction and analysis were done only on those that reported utilization of professional health care providers.

Using a textual approach, text data were coded using both predetermined and emerging codes [28]. They were then tabulated, analyzed, categorized into themes and integrated into a narrative synthesis [29]. Exemplar quotations and author interpretations were also used to support the narrative synthesis. The following were the themes on barriers and facilitators of formal help-seeking: (1) psychosocial barriers/facilitators, which include social support from family and friends, perceived severity of mental illness, awareness of mental health issues, self-stigmatizing beliefs, treatment fears and other individual concerns; (2) socio-cultural barriers/facilitators, which include the perceived social norms and beliefs on mental health, social stigma, influence of religious beliefs, and language and acculturation factors; and (3) systemic/structural and economic barriers/facilitators, which include financial or employment status, the health care system and its accessibility, availability and affordability, and ethnicity, nativity or immigration status.

Results

Study and participant characteristics

The 15 studies were published between 2002 and 2018. Five studies were conducted in the US, four in the Philippines and one study each was done in Australia, Canada, Iceland, Israel and Norway. One study included participants working in different countries, the majority were in the Middle East. Data extracted from the four studies done in the Philippines were used to report on the help-seeking behaviors and attitudes, and barriers/facilitators to help-seeking of local Filipinos, while the ten studies conducted in different countries were used to report on help-seeking of overseas Filipinos. Nine studies were quantitative and used a cross-sectional design except for one cohort study; the majority of them used research-validated questionnaires. Four studies used mixed methods with surveys and open-ended questionnaires, and another two were purely qualitative studies that used interviews and focus group discussions. Only three studies recruited participants through random sampling and the rest used purposive sampling methods. All quantitative studies used questionnaires in measures of formal help-seeking behaviors, and western-standardized measures to assess participants’ attitudes towards help-seeking. Qualitative studies utilized semi-structured interview guides that were developed to explore the psychological help-seeking of participants.

A total of 5096 Filipinos aged 17–70 years participated in the studies. Additionally, 13 studies reported on the mean age of participants, with the computed overall mean age at 39.52 (SD 11.34). The sample sizes in the quantitative studies ranged from 70 to 2285, while qualitative studies ranged from 10 to 25 participants. Of the participants, 59% (n = 3012) were female which is probably explained by five studies focusing on Filipino women. Ten studies were conducted in community settings, five in health or social centre-based settings and 1 in a university (Table 1).

Formal help-seeking behaviors

12 studies examined the formal help-seeking behaviors of Filipinos (Table 2), eight of them were from community-based studies and four were from centre-based studies. Nine studies reported on formal help-seeking of overseas Filipinos and three reported on local Filipinos.

Community-based vs health/social centres Data from quantitative community studies show that the rates of formal help-seeking behaviors among the Filipino general population ranged from 2.2% [30] to 17.5% [6]. This was supported by reports from qualitative studies where participants did not seek help at all. The frequency of reports of formal help-seeking from studies conducted in crisis centres and online counseling tended to be higher. For instance, the rate of engagement in online counseling among overseas Filipinos was 10.68% [31], those receiving treatment in crisis centers was 39.32% [17] while 100% of participants who were victims of intimate partner violence were already receiving help from a women’s support agency [8, 32].

Local vs overseas Filipinos’ formal help-seeking The rate of formal psychological help-seeking of local Filipinos was at 22.19% [12] while overseas rates were lower and ranged from 2.2% of Filipino Americans [30] to 17.5% of Filipinos in Israel [6]. Both local and overseas Filipinos indicated that professional help is sought only as a last resort because they were more inclined to get help from family and friends or lay network [7, 16].

Attitudes towards formal help-seeking

13 studies reported on participants’ attitudes towards seeking formal help. Seven studies identified family and friends as preferred sources of help [7, 14, 16] rather than mental health specialists and other professionals even when they were already receiving help from them [17, 32]. When Filipinos seek professional help, it is usually done in combination with other sources of care [13] or only used when the mental health problem is severe [14, 16, 33]. Other studies reported that in the absence of social networks, individuals prefer to rely on themselves [32, 33].

Community-based vs health/social centres Community-based studies reported that Filipinos have negative attitudes marked by low stigma tolerance towards formal help-seeking [7, 14, 16]. However, different findings were reported by studies conducted in crisis centres. Hechanova et al. found a positive attitude towards help-seeking among users of online counseling [31], whereas Cabbigat and Kangas found that Filipinos in crisis centres still prefer receiving help from religious clergy or family members, with mental health units as the least preferred setting in receiving help [17]. This is supported by the findings of Shoultz and her colleagues who reported that Filipino women did not believe in disclosing their problems to others [32].

Local vs overseas Filipinos Filipinos, regardless of location, have negative attitudes towards help-seeking, except later-generation Filipino migrants who have been acculturated in their host countries and tended to have more positive attitudes towards mental health specialists [10, 13, 15, 34]. However, this was only cited in quantitative studies. Qualitative studies reported the general reluctance of both overseas and local Filipinos to seek help.

Barriers in formal help-seeking

All 15 studies examined a range of barriers in psychological help-seeking (Table 3). The most commonly endorsed barriers were: (1) financial constraints due to high cost of service, lack of health insurance, or precarious employment condition; (2) self-stigma, with associated fear of negative judgment, sense of shame, embarrassment and being a disgrace, fear of being labeled as ‘crazy’, self-blame and concern for loss of face; and (3) social stigma that puts the family’s reputation at stake or places one’s cultural group in bad light.

Local vs overseas Filipinos In studies conducted among overseas Filipinos, strong adherence to Asian values of conformity to norms is an impediment to help-seeking but cited only in quantitative studies [10, 13, 15, 34] while perceived resilience, coping ability or self-reliance was mentioned only in qualitative studies [14, 16, 33]. Other common barriers to help-seeking cited by overseas Filipinos were inaccessibility of mental health services, immigration status, sense of religiosity, language problem, experience of discrimination and lack of awareness of mental health needs [10, 13, 18, 34]. Self-reliance and fear of being a burden to others as barriers were only found among overseas Filipinos [6, 16, 32]. On the other hand, local Filipinos have consistently cited the influence of social support as a hindrance to help-seeking [7, 17].

Stigmatized attitude towards mental health and illness was reported as topmost barriers to help-seeking among overseas and local Filipinos. This included notions of mental illness as a sign of personal weakness or failure of character resulting to loss of face. There is a general consensus in these studies that the reluctance of Filipinos to seek professional help is mainly due to their fear of being labeled or judged negatively, or even their fear of fueling negative perceptions of the Filipino community. Other overseas Filipinos were afraid that having mental illness would affect their jobs and immigration status, especially for those who are in precarious employment conditions [6, 16].

Facilitators of formal help-seeking

All 15 studies discussed facilitators of formal help-seeking, but the identified enablers were few (Table 4). Among the top and commonly cited factors that promote help-seeking are: (1) perceived severity of the mental health problem or awareness of mental health needs; (2) influence of social support, such as the presence/absence of family and friends, witnessing friends seeking help, having supportive friends and family who encourage help-seeking, or having others taking the initiative to help; and (3) financial capacity.

Local vs overseas Filipinos Studies on overseas Filipinos frequently cited financial capacity, immigration status, language proficiency, lower adherence to Asian values and stigma tolerance as enablers of help-seeking [15, 30, 32, 34], while studies done on local Filipinos reported that awareness of mental health issues and previous positive experience of seeking help serve as facilitator [7, 12].

Community-based vs health/social centres Those who were receiving help from crisis centres mentioned that previous positive experience with mental health professionals encouraged their formal help-seeking [8, 17, 31]. On the other hand, community-based studies cited the positive influence of encouraging family and friends as well as higher awareness of mental health problems as enablers of help-seeking [12, 14, 16].

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first systematic review conducted on psychological help-seeking among Filipinos, including its barriers and facilitators. The heterogeneity of participants (e.g., age, gender, socio-economic status, geographic location or residence, range of mental health problems) was large.

Filipino mental health help-seeking behavior and attitudes The rate of mental health problems appears to be high among Filipinos both local and overseas, but the rate of help-seeking is low. This is consistent with findings of a study among Chinese immigrants in Australia which reported higher psychological distress but with low utilization of mental health services [35]. The actual help-seeking behavior of both local and overseas Filipinos recorded at 10.72% (n = 461) is lower than the 19% of the general population in the US [36] and 16% in the United Kingdom (UK) [37], and even far below the global prevalence rate of 30% of people with mental illness receiving treatment [38]. This finding is also comparable with the low prevalence rate of mental health service use among the Chinese population in Hong Kong [39] and in Australia [35], Vietnamese immigrants in Canada [30], East Asian migrants in North America [41] and other ethnic minorities [42] but is in sharp contrast with the increased use of professional help among West African migrants in The Netherlands [43].

Most of the studies identified informal help through family and friends as the most widely utilized source of support, while professional service providers were only used as a last resort. Filipinos who are already accessing specialist services in crisis centres also used informal help to supplement professional help. This is consistent with reports on the frequent use of informal help in conjunction with formal help-seeking among the adult population in UK [44]. However, this pattern contrasts with informal help-seeking among African Americans who are less likely to seek help from social networks of family and friends [45]. Filipinos also tend to use their social networks of friends and family members as ‘go-between’ [46] for formal help, serving to intercede between mental health specialists and the individual. This was reiterated in a study by Shoultz et al. (2009) in which women who were victims of violence are reluctant to report the abuse to authorities but felt relieved if neighbours and friends would interfere for professional help in their behalf [32].

Different patterns of help-seeking among local and overseas Filipinos were evident and may be attributed to the differences in the health care system of the Philippines and their host countries. For instance, the greater use of general medical services by overseas Filipinos is due to the gatekeeper role of general practitioners (GP) in their host countries [47] where patients have to go through their GPs before they get access to mental health specialists. In contrast, local Filipinos have direct access to psychiatrists or psychologists without a GP referral. Additionally, those studies conducted in the Philippines were done in urban centers where participants have greater access to mental health specialists. While Filipinos generally are reluctant to seek help, later-generation overseas Filipinos have more positive attitudes towards psychological help-seeking. Their exposure and acculturation to cultures that are more tolerant of mental health stigma probably influenced their more favorable attitude [41, 48].

Prominent barrier themes in help-seeking Findings of studies on frequently endorsed barriers in psychological help-seeking are consistent with commonly reported impediments to health care utilization among Filipino migrants in Australia [49] and Asian migrants in the US [47, 50]. The same barriers in this review, such as preference for self-reliance as alternative coping strategy, poor mental health awareness, perceived stigma, are also identified in mental health help-seeking among adolescents and young adults [51] and among those suffering from depression [52].

Social and self-stigmatizing attitudes to mental illness are prominent barriers to help-seeking among Filipinos. Social stigma is evident in their fears of negative perception of the Filipino community, ruining the family reputation, or fear of social exclusion, discrimination and disapproval. Self-stigma manifests in their concern for loss of face, sense of shame or embarrassment, self-blame, sense of being a disgrace or being judged negatively and the notion that mental illness is a sign of personal weakness or failure of character [16]. The deterrent role of mental health stigma is consistent with the findings of other studies [51, 52]. Overseas Filipinos who are not fully acculturated to the more stigma-tolerant culture of their host countries still hold these stigmatizing beliefs. There is also a general apprehension of becoming a burden to others.

Practical barriers to the use of mental health services like accessibility and financial constraints are also consistently rated as important barriers by Filipinos, similar to Chinese Americans [53]. In the Philippines where mental health services are costly and inaccessible [54], financial constraints serve as a hindrance to formal help-seeking, as mentioned by a participant in the study of Straiton and his colleagues, “In the Philippines… it takes really long time to decide for us that this condition is serious. We don’t want to use our money right away” [14, p.6]. Local Filipinos are confronted with problems of lack of mental health facilities, services and professionals due to meager government spending on health. Despite the recent ratification of the Philippines’ Mental Health Act of 2018 and the Universal Health Care Act of 2019, the current coverage for mental health services provided by the Philippine Health Insurance Corporation only amounts to US$154 per hospitalization and only for acute episodes of mental disorders [55]. Specialist services for mental health in the Philippines are restricted in tertiary hospitals located in urban areas, with only one major mental hospital and 84 psychiatric units in general hospitals [1].

Overseas Filipinos cited the lack of health insurance and immigration status without health care privileges as financial barrier. In countries where people have access to universal health care, being employed is a barrier to psychological help-seeking because individuals prefer to work instead of attending medical check-ups or consultations [13]. Higher income is also associated with better mental health [56] and hence, the need for mental health services is low, whereas poor socio-economic status is related to greater risk of developing mental health problems [57, 58]. Lack of familiarity with healthcare system in host countries among new Filipino migrants also discourages them from seeking help.

Studies have shown that reliance on, and accessibility of sympathetic, reliable and trusted family and friends are detrimental to formal help-seeking since professional help is sought only in the absence of this social support [6, 8]. This is consistent with the predominating cultural values that govern Filipino interpersonal relationships called kapwa (or shared identity) in which trusted family and friends are considered as “hindi-ibang-tao” (one-of-us/insider), while doctors or professionals are seen as “ibang-tao” (outsider) [59]. Filipinos are apt to disclose and be more open and honest about their mental illness to those whom they considered as “hindi-ibang-tao” (insider) as against those who are “ibang-tao” (outsider), hence their preference for family members and close friends as source of informal help [59]. For Filipinos, it is difficult to trust a mental health specialist who is not part of the family [60].

Qualitative studies in this review frequently mentioned resilience and self-reliance among overseas Filipinos as barriers to help-seeking. As an adaptive coping strategy for adversity [61], overseas Filipinos believe that they were better equipped in overcoming emotional challenges of immigration [16] without professional assistance [14]. It supports the findings of studies on overseas Filipino domestic workers who attributed their sense of well-being despite stress to their sense of resilience which prevents them from developing mental health problems [62] and among Filipino disaster survivors who used their capacity to adapt as protective mechanism from experience of trauma [63]. However, self-reliant individuals also tend to hold stigmatizing beliefs on mental health and as such resort to handling problems on their own instead of seeking help [51, 64].

Prominent facilitator themes in help-seeking In terms of enablers of psychological help-seeking, only a few facilitators were mentioned in the studies, which supported findings in other studies asserting that factors that promote help-seeking are less often emphasized [42, 51].

Consistent with other studies [44, 49], problem severity is predictive of intention to seek help from mental health providers [18, 30] because Filipinos perceive that professional services are only warranted when symptoms have disabling effects [5, 53]. As such, those who are experiencing heightened emotional distress were found to be receptive to intervention [17]. In most cases, symptom severity is determined only when somatic or behavioral symptoms manifest [13] or occupational dysfunction occurs late in the course of the mental illness [65]. This is most likely due to the initial denial of the problem [66] or attempts at maintaining normalcy of the situation as an important coping mechanism [67]. Furthermore, this poses as a hindrance to any attempts at early intervention because Filipinos are likely to seek professional help only when the problem is severe or has somatic manifestations. It also indicates the lack of preventive measure to avert any deterioration in mental health and well-being.

More positive attitudes towards help-seeking and higher rates of mental health care utilization have been found among later-generation Filipino immigrants or those who have acquired residency status in their host country [10, 15]. Immigration status and length of stay in the host country are also associated with language proficiency, higher acculturation and familiarity with the host culture that are more open to discussing mental health issues [13], which present fewer barriers in help-seeking. This is consistent with facilitators of formal help-seeking among other ethnic minorities, such as acculturation, social integration and positive attitude towards mental health [43].

Cultural context of Filipinos’ reluctance to seek help Several explanations have been proposed to account for the general reluctance of Filipinos to seek psychological help. In Filipino culture, mental illness is attributed to superstitious or supernatural causes, such as God’s will, witchcraft, and sorcery [68, 69], which contradict the biopsychosocial model used by mental health care professionals. Within this cultural context, Filipinos prefer to seek help from traditional folk healers who are using religious rituals in their healing process instead of availing the services of professionals [70, 71]. This was reaffirmed by participants in the study of Thompson and her colleagues who said that “psychiatrists are not a way to deal with emotional problems” [74, p.685]. The common misconception on the cause and nature of mental illness, seeing it as temporary due to cold weather [14] or as a failure in character and as an individual responsibility to overcome [16, 72] also discourages Filipinos from seeking help.

Synthesis of the studies included in the review also found conflicting findings on various cultural and psychosocial influences that served both as enablers and deterrents to Filipino help-seeking, namely: (1) level of spirituality; (2) concern on loss of face or sense of shame; and (3) presence of social support.

Level of spirituality Higher spirituality or greater religious beliefs have disparate roles in Filipino psychological help-seeking. Some studies [8, 14, 16] consider it a hindrance to formal help-seeking, whereas others [10, 15] asserted that it can facilitate the utilization of mental health services [15, 73]. Being predominantly Catholics, Filipinos had drawn strength from their religious faith to endure difficult situations and challenges, accordingly ‘leaving everything to God’ [74] which explains their preference for clergy as sources of help instead of professional mental health providers. This is connected with the Filipino attribution of mental illness to spiritual or religious causes [62] mentioned earlier. On the contrary, Hermansdottir and Aegisdottir argued that there is a positive link between spirituality and help-seeking, and cited connectedness with host culture as mediating factor [15]. Alternately, because higher spirituality and religiosity are predictors of greater sense of well-being [75], there is, thus, a decreased need for mental health services.

Concern on loss of face or sense of shame The enabler/deterrent role of higher concern on loss of face and sense of shame on psychological help-seeking was also identified. The majority of studies in this review asserted the deterrent role of loss of face and stigma consistent with the findings of other studies [51], although Clement et al. stated that stigma is the fourth barrier in deterring help-seeking [76]. Mental illness is highly stigmatized in the Philippines and to avoid the derogatory label of ‘crazy’, Filipinos tend to conceal their mental illness and consequently avoid seeking professional help. This is aligned with the Filipino value of hiya (sense of propriety) which considers any deviation from socially acceptable behavior as a source of shame [11]. The stigmatized belief is reinforced by the notion that formal help-seeking is not the way to deal with emotional problems, as reflected in the response of a Filipino participant in the study by Straiton et. al., “It has not occurred to me to see a doctor for that kind of feeling” [14, p.6]. However, other studies in this review [12, 13] posited contrary views that lower stigma tolerance and higher concern for loss of face could also motivate psychological help-seeking for individuals who want to avoid embarrassing their family. As such, stigma tolerance and loss of face may have a more nuanced influence on help-seeking depending on whether the individual avoids the stigma by not seeking help or prevent the stigma by actively seeking help.

Presence of social support The contradictory role of social networks either as helpful or unhelpful in formal help-seeking was also noted in this review. The presence of friends and family can discourage Filipinos from seeking professional help because their social support serves as protective factor that buffer one’s experience of distress [77, 78]. Consequently, individuals are less likely to use professional services [42, 79]. On the contrary, other studies have found that the presence of friends and family who have positive attitudes towards formal help-seeking can promote the utilization of mental health services [8, 80]. Friends who sought formal help and, thus, serve as role models [14], and those who take the initiative in seeking help for the distressed individual [32] also encourage such behavior. Thus, the positive influence of friends and family on mental health and formal help-seeking of Filipinos is not merely to serve only as emotional buffer for stress, but to also favourably influence the decision of the individual to seek formal help.

Research implications of findings

This review highlights particular evidence gaps that need further research: (1) operationalization of help-seeking behavior as a construct separating intention and attitude; (2) studies on actual help-seeking behavior among local and overseas Filipinos with identified mental health problems; (3) longitudinal study on intervention effectiveness and best practices; (4) studies that triangulate findings of qualitative studies with quantitative studies on the role of resilience and self-reliance in help-seeking; and (5) factors that promote help-seeking.

Some studies in this review reported help-seeking intention or attitude as actual behaviors even though they are separate constructs, hence leading to reporting biases and misinterpretations. For instance, the conflicting findings of Tuliao et al. [12] on the negative association of loss of face with help-seeking attitude and the positive association between loss of face and intention to seek help demonstrate that attitudes and intentions are separate constructs and, thus, need further operationalization. Future research should strive to operationalize concretely these terms through the use of robust measurement tools and systematic reporting of results. There is also a lack of data on the actual help-seeking behaviors among Filipinos with mental illness as most of the reports were from the general population and on their help-seeking attitudes and intentions. Thus, research should focus on those with mental health problems and their actual utilization of healthcare services to gain a better understanding of how specific factors prevent or promote formal help-seeking behaviors.

Moreover, the majority of the studies in this review were descriptive cross-sectional studies, with only one cohort analytic study. Future research should consider a longitudinal study design to ensure a more rigorous and conclusive findings especially on testing the effectiveness of interventions and documenting best practices. Because of the lack of quantitative research that could triangulate the findings of several qualitative studies on the detrimental role of resilience and self-reliance, quantitative studies using pathway analysis may help identify how these barriers affect help-seeking. A preponderance of studies also focused on discussing the roles of barriers in help-seeking, but less is known about the facilitators of help-seeking. For this reason, factors that promote help-seeking should be systematically investigated.

Practice, service delivery and policy implications

Findings of this review also indicate several implications for practice, service delivery, intervention and policy. Cultural nuances that underlie help-seeking behavior of Filipinos, such as the relational orientation of their interactions [81], should inform the design of culturally appropriate interventions for mental health and well-being and improving access and utilization of health services. Interventions aimed at improving psychological help-seeking should also target friends and family as potential and significant influencers in changing help-seeking attitude and behavior. They may be encouraged to help the individual to seek help from the mental health professional. Other approaches include psychoeducation that promotes mental health literacy and reduces stigma which could be undertaken both as preventive and treatment strategies because of their positive influence on help-seeking. Strategies to reduce self-reliance may also be helpful in encouraging help-seeking.

This review also has implications for structural changes to overcome economic and other practical barriers in Filipino seeking help for mental health problems. Newly enacted laws on mental health and universal healthcare in the Philippines may jumpstart significant policy changes, including increased expenditure for mental health treatment.

Since lack of awareness of available services was also identified as significant barrier, overseas Filipinos could be given competency training in utilizing the health care system of host countries, possibly together with other migrants and ethnic minorities. Philippine consular agencies in foreign countries should not merely only resort to repatriation acts, but could also take an active role in service delivery especially for overseas Filipinos who experience trauma and/or may have immigration-related constraints that hamper their access to specialist care.

Limitations of findings

A crucial limitation of studies in this review is the use of different standardized measures of help-seeking that render incomparable results. These measures were western-based inventories, and only three studies mentioned using cultural validation, such as forward-and-back-translations, to adapt them to cross-cultural research on Filipino participants. This may pose as a limitation on the cultural appropriateness and applicability of foreign-made tests [73] in capturing the true essence of Filipino experience and perspectives [74]. Additionally, the majority of the studies used non-probability sampling that limits the generalizability of results. They also failed to measure the type of assistance or actual support sought by Filipinos, such as psychoeducation, referral services, supportive counseling or psychotherapy, and whether or not they are effective in addressing mental health concerns of Filipinos. Another inherent limitation of this review is the lack of access to grey literature, such as thesis and dissertations published in other countries, or those published in the Philippines and are not available online. A number of studies on multi-ethnic studies with Filipino participants do not provide disaggregated data, which limits the scope and inclusion of studies in this review.

Conclusion

This review has confirmed the low utilization of mental health services among Filipinos regardless of their locations, with mental health stigma as a primary barrier resilience and self-reliance as coping strategies were also cited, especially in qualitative studies, but may be important in addressing issues of non-utilization of mental health services. Social support and problem severity were cited as prominent facilitators in help-seeking. However, different structural, cultural and practical barriers and facilitators of psychological help-seeking between overseas and local Filipinos were also found.

References

WHO (2017) Mental health atlas 2017. World Health Organization

Redaniel MT, Lebanan-Dalida MA, Gunnell D (2011) Suicide in the Philippines: time trend analysis (1974–2005) and literature review. BMC Public Health 11(1):536

WHO (2011) Mental health atlas 2011. World Health Organization

Nguyen D, Bornheimer LA (2014) Mental health service use types among Asian Americans with a psychiatric disorder: Considerations of culture and need. J Behav Health Serv Res 41(4):520–528

Nicdao EG, Duldulao AA, Takeuchi DT (2015) Psychological distress, nativity, and help-seeking among Filipino Americans. In: Education, social factors, and health beliefs in health and health care services. Emerald Group Publishing Limited, pp 107–120

Green O, Ayalon L (2016) Whom do migrant home care workers contact in the case of work-related abuse? An exploratory study of help-seeking behaviors. J Interpers Violence 31(19):3236–3256

Ho GW, Bressington D, Leung SF, Lam K, Leung A, Molassiotis A et al (2018) Depression literacy and health-seeking attitudes in the Western Pacific region: a mixed-methods study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 53(10):1039–1049

Bernardo AB, Estrellado AF (2017) Locus-of-hope and help-seeking intentions of Filipino women victims of intimate partner violence. Curr Psychol 36(1):66–75

Kessler RC, Frank RG, Edlund M, Katz SJ, Lin E, Leaf P (1997) Differences in the use of psychiatric outpatient services between the United States and Ontario. N Engl J Med 336(8):551–557

Abe-Kim J, Takeuchi DT, Hong S, Zane N, Sue S, Spencer MS et al (2007) Use of mental health–related services among immigrant and US-born Asian Americans: results from the National Latino and Asian American study. Am J Public Health 97(1):91–98

Tuliao AP (2014) Mental health help seeking among Filipinos: a review of the literature. Asia Pac J Couns Psychother 5(2):124–136

Tuliao AP, Velasquez PAE, Bello AM, Pinson MJT (2016) Intent to seek counseling among Filipinos: examining loss of face and gender. Couns Psychol 44(3):353–382

Gong F, Gage SL, Tacata LA Jr (2003) Helpseeking behavior among Filipino Americans: a cultural analysis of face and language. J Community Psychol 31(5):469–488

Straiton ML, Ledesma HML, Donnelly TT (2018) “It has not occurred to me to see a doctor for that kind of feeling”: a qualitative study of Filipina immigrants’ perceptions of help seeking for mental health problems. BMC Women’s Health 18(1):73

Hermannsdóttir BS, Aegisdottir S (2016) Spirituality, connectedness, and beliefs about psychological services among filipino immigrants in Iceland. Counsel Psychol 44(4):546–572

Vahabi M, Wong JP (2017) Caught between a rock and a hard place: mental health of migrant live-in caregivers in Canada. BMC Public Health 17(1):498

Cabbigat FK, Kangas M (2018) Help-seeking behaviors in non-offending caregivers of abused children in the Philippines. J Aggress Maltreat Trauma 27(5):555–573

Nguyen D, Lee R (2012) Asian immigrants' mental health service use: an application of the life course perspective. Asian Am J Psychol 3(1):53

Rickwood D, Thomas K (2012) Conceptual measurement framework for help-seeking for mental health problems. Psychol Res Behav Manag 5:173

Divin N, Harper P, Curran E, Corry D, Leavey G (2018) Help-seeking measures and their use in adolescents: a systematic review. Adolesc Res Rev 3:113–122

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Prisma Group (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 6(7):e1000097

Singh J (2013) Critical appraisal skills programme. J Pharmacol Pharmacotherapeutics 4(1):76

E Effective Public Health Practice Project (1998) Quality assessment tool for quantitative studies

Hong QN, Fàbregues S, Bartlett G, Boardman F, Cargo M, Dagenais P et al (2018) The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Educ Inf 34(4):285–291

Boland A, Cherry G, Dickson R (2017) Doing a systematic review: a student's guide. Sage, Thousand Oaks

Charrois TL (2015) Systematic reviews: what do you need to know to get started? Can J Hosp Pharm 68(2):144

Sandelowski M, Barroso J, Voils CI (2007) Using qualitative metasummary to synthesize qualitative and quantitative descriptive findings. Res Nurs Health 30(1):99–111

Cresswell J, Cresswell D (2018) Research design: Qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches. SAGE, London

Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, Petticrew M, Arai L, Rodgers M, Britten N, Roen K, Duffy S (2006) Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. A product from the ESRC methods programme Version 1:b92

Nguyen D (2011) Acculturation and perceived mental health need among older Asian immigrants. J Behav Health Serv Res 38(4):526–533

Hechanova MRM, Tuliao AP, Teh LA, Alianan AS, Acosta A (2013) Problem severity, technology adoption, and intent to seek online counseling among overseas Filipino workers. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 16(8):613–617

Shoultz J, Magnussen L, Manzano H, Arias C, Spencer C (2010) Listening to Filipina women: perceptions, responses and needs regarding intimate partner violence. Issues Ment Health Nurs 31(1):54–61

Thompson S, Manderson L, Woelz-Stirling N, Cahill A, Kelaher M (2002) The social and cultural context of the mental health of Filipinas in Queensland. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 36(5):681–687

David E (2010) Cultural mistrust and mental health help-seeking attitudes among Filipino Americans. Asian Am J Psychol 1(1):57

Lu SH, Dear BF, Johnston L, Wootton BM, Titov N (2014) An internet survey of emotional health, treatment seeking and barriers to accessing mental health treatment among Chinese-speaking international students in Australia. Couns Psychol Q 27(1):96–108

Mojtabai R, Olfson M, Mechanic D (2002) Perceived need and help-seeking in adults with mood, anxiety, or substance use disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry 59(1):77–84

Oliver MI, Pearson N, Coe N, Gunnell D (2005) Help-seeking behaviour in men and women with common mental health problems: cross-sectional study. Br J Psychiatry 186(4):297–301

Henderson C, Evans-Lacko S, Thornicroft G (2013) Mental illness stigma, help seeking, and public health programs. Am J Public Health 103(5):777–780

Mo PK, Mak WW (2009) Help-seeking for mental health problems among Chinese. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 44(8):675–684

Kirmayer LJ, Weinfeld M, Burgos G, Du Fort GG, Lasry J, Young A (2007) Use of health care services for psychological distress by immigrants in an urban multicultural milieu. Can J Psychiatry 52(5):295–304

Na S, Ryder AG, Kirmayer LJ (2016) Toward a culturally responsive model of mental health literacy: facilitating help-seeking among East Asian immigrants to North America. Am J Community Psychol 58(1–2):211–225

Li W, Dorstyn DS, Denson LA (2016) Predictors of mental health service use by young adults: a systematic review. Psychiatric Serv 67(9):946–956

Knipscheer JW, Kleber RJ (2008) Help-seeking behavior of west African Migrants. J Community Psychol 36(7):915–928

Brown JS, Evans-Lacko S, Aschan L, Henderson MJ, Hatch SL, Hotopf M (2014) Seeking informal and formal help for mental health problems in the community: a secondary analysis from a psychiatric morbidity survey in South London. BMC Psychiatry 14(1):275

Snowden LR (1998) Racial differences in informal help seeking for mental health problems. J Community Psychol 26(5):429–438

Pasco ACY, Morse JM, Olson JK (2004) Cross-cultural relationships between nurses and Filipino Canadian patients. J Nurs Scholarsh 36(3):239–246

Clough J, Lee S, Chae DH (2013) Barriers to health care among Asian immigrants in the United States: a traditional review. J Health Care Poor Underserved 24(1):384–403

Ihara ES, Chae DH, Cummings JR, Lee S (2014) Correlates of mental health service use and type among Asian Americans. Adm Policy Mental Health Mental Health Serv Res 41(4):543–551

Maneze D, DiGiacomo M, Salamonson Y, Descallar J, Davidson PM (2015) Facilitators and barriers to health-seeking behaviours among Filipino migrants: inductive analysis to inform health promotion. BioMed Res Int 2015:506269

Choi JY (2009) Contextual effects on health care access among immigrants: Lessons from three ethnic communities in Hawaii. Soc Sci Med 69(8):1261–1271

Gulliver A, Griffiths KM, Christensen H (2010) Perceived barriers and facilitators to mental health help-seeking in young people: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry 10(1):113

Doblyte S, Jiménez-Mejías E (2017) Understanding help-seeking behavior in depression: a qualitative synthesis of patients’ experiences. Qual Health Res 27(1):100–113

Kung WW (2004) Cultural and practical barriers to seeking mental health treatment for Chinese Americans. J Community Psychol 32(1):27–43

Saxena S, Thornicroft G, Knapp M, Whiteford H (2007) Resources for mental health: scarcity, inequity, and inefficiency. Lancet 370(9590):878–889

Tomacruz S (2018) PhilHealth should cover psychiatric consultation fees—Angara. Rappler. https://www.rappler.com/nation/204570-senator-sonny-angara-philhealth-consultation-fees-mental-illnesses. Accessed 22 Oct 2019

Cuesta MB, Budría S (2015) Income deprivation and mental well-being: the role of non-cognitive skills. Econ Human Biol 17:16–28

Reiss F (2013) Socioeconomic inequalities and mental health problems in children and adolescents: a systematic review. Soc Sci Med 90:24–31

Pereira B, Andrew G, Pednekar S, Pai R, Pelto P, Patel V (2007) The explanatory models of depression in low income countries: listening to women in India. J Affect Disord 102(1–3):209–218

Pe‐Pua R, Protacio‐Marcelino EA (2000) Sikolohiyang Pilipino (Filipino psychology): a legacy of Virgilio G. Enriquez. Asian J Soc Psychol 3(1):49–71.https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-839X.00054

Schumacher HE, Guthrie GM (1984) Culture and counseling in the Philippines. Int J Intercult Relat 8(3):241–253

Luthar S, Cicchetti D (2000) The construct of resilience: implications for interventions and social policies. Dev Psychopathol 12:857–885

van der Ham AJ, Ujano-Batangan MT, Ignacio R, Wolffers I (2014) Toward healthy migration: an exploratory study on the resilience of migrant domestic workers from the Philippines. Transcult Psychiatry 51(4):545–568

Hechanova MRM, Waelde LC, Docena PS, Alampay LP, Alianan AS, Flores MJB et al (2015) The development and initial evaluation of Katatagan: a resilience intervention for Filipino disaster survivors. Philipp J Psychol 48(2):105–131

Jennings KS, Cheung JH, Britt TW, Goguen KN, Jeffirs SM, Peasley AL et al (2015) How are perceived stigma, self-stigma, and self-reliance related to treatment-seeking? A three-path model. Psychiatr Rehabil J 38(2):109

Huang ZJ, Wong FY, Ronzio CR, Yu SM (2007) Depressive symptomatology and mental health help-seeking patterns of U.S.- and foreign-born mothers. Matern Child Health J 11(3):257–267

Ali K, Farrer L, Fassnacht DB, Gulliver A, Bauer S, Griffiths KM (2017) Perceived barriers and facilitators towards help-seeking for eating disorders: a systematic review. Int J Eat Disord 50(1):9–21

Straiton ML, Ledesma HML, Donnelly TT (2017) A qualitative study of Filipina immigrants’ stress, distress and coping: the impact of their multiple, transnational roles as women. BMC Womens Health 17(1):72

Tan ML, Tan MT (2008) Revisiting usog, pasma, kulam. UP Press, Quezon City

Edman JL, Kameoka VA (1997) Cultural differences in illness schemas: an analysis of Filipino and American illness attributions. J Cross Cult Psychol 28(3):252–265

Hwang W, Miranda J, Chung C (2007) Psychosis and shamanism in a Filipino–American immigrant. Cult Med Psychiatry 31(2):251–269

Lovering S (2006) Cultural attitudes and beliefs about pain. J Transcult Nurs 17(4):389–395

Thompson S, Hartel G, Manderson L, Stirling N, Kelaher M (2002) The mental health status of Filipinas in Queensland. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 36(5):674–680

Abe-Kim J, Gong F, Takeuchi D (2004) Religiosity, spirituality, and help-seeking among Filipino Americans: religious clergy or mental health professionals? J Community Psychol 32(6):675–689

Lagman RA, Yoo GJ, Levine EG, Donnell KA, Lim HR (2014) “Leaving it to God” religion and spirituality among Filipina immigrant breast cancer survivors. J Relig Health 53(2):449–460

Cohen AB (2002) The importance of spirituality in well-being for Jews and Christians. J Happiness Stud 3(3):287–310

Clement S, Schauman O, Graham T, Maggioni F, Evans-Lacko S, Bezborodovs N et al (2015) What is the impact of mental health-related stigma on help-seeking? A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. Psychol Med 45(1):11–27

Gee GC, Chen J, Spencer MS, See S, Kuester OA, Tran D et al (2006) Social support as a buffer for perceived unfair treatment among Filipino Americans: differences between San Francisco and Honolulu. Am J Public Health 96(4):677–684

Coker AL, Smith PH, Thompson MP, McKeown RE, Bethea L, Davis KE (2002) Social support protects against the negative effects of partner violence on mental health. J Womens Health Gend Based 11(5):465–476

Miville ML, Constantine MG (2006) Sociocultural predictors of psychological help-seeking attitudes and behavior among Mexican American college students. Cult Divers Ethnic Minority Psychol 12(3):420

Tuliao AP, Velasquez PAE (2017) Online counselling among Filipinos: do Internet-related variables matter? Asia Pac J Couns Psychother 8(1):53–65

Mujtaba BG, Balboa A (2009) Comparing Filipino and American task and relationship orientations. J Appl Manag Entrepreneurship 14(2):82

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests in this work.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Martinez, A.B., Co, M., Lau, J. et al. Filipino help-seeking for mental health problems and associated barriers and facilitators: a systematic review. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 55, 1397–1413 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-020-01937-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-020-01937-2