Abstract

Purpose

Evidence-based policy making is increasingly being advocated by governments and scholars. To show that policies are informed by evidence, policy-related documents that cite external sources should ideally provide direct access to, and accurately represent, the referenced source and the evidence it provides. Our aim was to find a way to systematically assess the prevalence of referencing accuracy and accessibility issues in referenced statements selected from a sample of mental health-related policy documents.

Method

236 referenced statements were selected from 10 mental health-related policy documents published between 2013 and 2018. Policy documents were chosen as the focus of this investigation because of their relative accessibility and impact on clinical practice. Statements were rated against their referenced sources in terms of the (i) content accuracy in relation to the information provided by the referenced source and (ii) degree of accessibility of the source and the required evidence from the references provided.

Results

Of the 236 statements, 141 (59.7%) accurately represented the referenced source, 45 (19.1%) contained major errors and 50 (21.2%) contained minor errors in accuracy. For accessibility, 126 (53.4%) directly referenced primary sources of evidence that supported the claims made, 36 (15.3%) contained indirect references, 18 (7.6%) provided ‘dead-end’ references, and 11 (4.7%) references were completely inaccessible.

Conclusions

With only slightly over half of all statements assessed providing fully accessible references and accurately representing the referenced source, these components of referencing quality deserve further attention if evidence-informed policy goals are to be achieved. The rating framework used in the current study proved to be a simple and straightforward method to assess these components and can provide a baseline against which interventions can be designed to improve referencing quality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The evidence-based policy (EBP) movement encourages the use of rigorous research and analysis to improve the decisions made by policy makers [1] and urges for transparency of evidence use during each stage of the decision-making process [2]. A substantial body of research has scrutinised the quality of references cited to support factual claims in research papers. In terms of referencing accuracy and accessibility of evidence, the medical fields investigated encompass psychiatry [3], manual therapy [4], major and minor infectious diseases [5], public health [6], veterinary science [7], nursing [8], amongst others. The methods used in these investigations provide a methodological approach with potential to be applied to evaluate how far claims about evidence in policy documents are supported. However, few such investigations have been conducted: for example, there have to date been no appraisals of policy documentation relevant to mental health. Such an assessment is relevant to evaluating the extent to which mental health-related policy documents are evidence based.

A largely consistent classification system has been used to quantify errors in referencing accuracy and accessibility in medical journals [3,4,5,6,7,8, 13]. First, quotation or content accuracy refers to whether the content of a factual statement reflects the assertions and findings of the referenced source. A misinterpretation or misreporting of the evidence is especially hazardous where mandates and recommendations regarding healthcare delivery are based on these claims. Errors in accuracy are commonly separated into (i) major errors, when the referenced statement is unsubstantiated, unrelated to, or contradicted by the original source that was referenced and (ii) minor errors, when there is an oversimplification, overgeneralisation or minor reporting inaccuracy, but errors that are not sufficiently deviant to be considered incoherent with the overall assertions of the original source. If such errors occur, there is a possibility for information to be distorted [9] or falsely amplified [10]. Accessibility, meanwhile, relates to the availability of trouble-free access to the evidence source, enabling readers to verify the claims made and to assess the evidence base behind the claim for themselves. Accessibility to referenced sources in the previous literature has predominantly focused on problems arising from indirect referencing. These are improper, secondary citations that fail to provide the primary source of the empirical evidence required to support the claim by itself, but instead contain further references to documents that do provide the primary source of evidence. Whilst indirect referencing is fairly common and arguably less of an issue compared to content inaccuracies, it can still be problematic because (i) original authors do not get the rightful credit for their work, (ii) minor inaccuracies can easily propagate to other documents in a ‘Chinese whispers’ manner, and (iii) continuous indirect referencing across multiple documents makes it difficult for readers to trace the evidence back to its original source to assess its credibility.

For policy documents, critical examinations of referencing quality have been relatively scarce. Only recently have assessments of evidence transparency been conducted, notably by the Institute for Government and Sense about Science in May 2015 to May 2016 [11] and July 2016 to July 2017 [12]. They recognised similar issues with referencing quality in policy proposals across other policy sectors. “Referencing quality” was highlighted as one of the eight main barriers to full transparency of evidence. However, like many other discussions that have touched on referencing quality as an issue, such assessments did not specifically assess the accessibility and accuracy of references used to substantiate factual claims. We argue this component should not be overlooked and should be spot-checked in an equivalent manner, because referencing errors may be a sign that writers may have not read [6] or comprehended the work [16]. Also, the lack of consensus or convention on what is expected from writers of such documents provides no evident approach for readers to anticipate the quality of referencing of each document, or whether such documents are expected to reference their sources at all. Also, these investigations examined policies produced by various governmental departments in terms of how transparent they were about the evidence use behind each stage of the policy-making process (i.e. diagnosis, proposal, implementation, testing and evaluation). Although one of the major findings that the authors highlighted included ‘referencing quality’ as one of the eight main barriers to full transparency of evidence, this was not the focal point of the spot checks and thus also was not, in a structured manner, integrated into the rating system within the transparency framework.

As mentioned earlier, however, there is a rich body of research examining referencing accuracy and accessibility in medical sciences. This has even progressed to several systematic reviews that attempted to quantify an average level of errors across an array of medical fields. The most recent and empirically vigorous of these was a systematic review of 15 studies that examined the accessibility and accuracy of referenced ‘facts’ across various medical fields [13]. It was estimated that the average prevalence of content inaccuracy across the studies was around 14.5% (95% confidence interval [CI] 10.5–18.6%). The majority (64.8%) of content errors found were major errors (95% CI 56.1–73.5%) and a minority (35.2%) were minor errors (95% CI 26.5–43.9%). The overall level of indirect referencing was estimated at approximately 10.4% (95% CI 3.4–17.5%).

Our study has three main aims. First, we will explore the feasibility of applying an existing rating framework previously used to systematically assess referencing quality in medical papers onto mental health policy documents, and to make any necessary modifications. Second, we will investigate how accessible sources of evidence are from referenced statements found in a selection of mental health policy documents published in the last 5 years in the UK. Thirdly, we aim to assess how accurately the referenced statements are in representing their evidence sources.

Method

Our study involved the extraction and analysis of evidence sources for references included in ten mental health policy documents published within the last 10 years in the United Kingdom. As no framework was so far available for scrutiny of referencing in policy documents, we adapted a framework developed for examining referencing in medical papers, initially piloting it to assess its feasibility in the appraisal of mental health policy documents.

Pilot

An initial pilot search and analysis was performed to assess the feasibility of appraising mental health policy documentation by adapting a common methodology and rating framework previously solely used to assess academic papers. This was so that necessary modifications could be identified, tested, and implemented prior to the main analysis. The framework was based from that used in Mogull (2017) [13], the most recent systematic review of studies that all utilised largely similar frameworks to assess content accuracy and referencing accessibility.

Search strategy

Mental health-relevant policy documents were identified through a web search of the United Kingdom governmental website https://www.gov.uk/government/publications conducted between November 2017 and June 2018. The search was limited to the term ‘mental health’ and to documents published within the last 5 years (2013–2018). Only publications accessible via the ‘Policy and Guidance’ section of the website, which comprised of the subsections ‘correspondence’, ‘guidance’, ‘independent reports’ and ‘policy papers’, were included. Policy areas of interest included subsections of Children and Young People, Community and Society, NHS, Public Health and Social Care and Welfare.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We defined mental health policy documents as any document published by a governmental department, an arm’s length body [15] related to the government such as Public Health England and NHS England, or Parliament, that (a) declared any form of governmental action, strategy or recommendations on any topic on or related to mental health and/or (b) provided guidance or regulations related to mental health, to be followed by the relevant professions and by providers and commissioners of services To ensure that the investigation captured a wide variety of sources, we sought policy documents that contained at least ten references to original scientific articles. We omitted documents that were primarily produced by independent organisations, as our particular interest pertained to the assessment of documents that were publicly supported and disseminated widely by governmental organisations.

Data extraction and analysis

49 referenced ‘factual’ statements were sampled from two documents. These documents were subsequently included in group of ten documents used in the main study. Factual statements were defined as statements that required the support of empirical evidence or assertions derived from such evidence that is provided by the cited source. This definition excluded statements where the reference were not explicitly used to support a factual assertion. For example, a referenced statement that used references to signpost relevant resources would not have qualified as a factual statement.

Two independent reviewers conducted the selection and assessment of factual statements. Statements were identified by arbitrarily choosing references from the reference lists of the included policy documents and then confirming whether the statement supported by the citation met inclusion criteria. Statements were required to meet the criteria that they were ‘factual’, did not reference more than one evidence source, and were in relation to providing evidence to support an overarching argument relevant to the recommendations provided by the given section. The eligibility of each statement was considered independently by two reviewers, and then collated to examine agreements and discrepancies. Discrepancies that could not be resolved through discussion were referred to a third reviewer. Statements were sampled until either 25 had been identified that were suitable for inclusion or the reference list had been exhausted. To reduce potential selection bias, the primary reviewer selected 75% of statements and a second reviewer independently selected 25% of statements used for the main analysis and no sources were accessed either prior to or during the selection process.

These factual statements were then compared against their referenced source to assess the level of accuracy and accessibility, and errors were classified based on the classification framework used by Mogull (2017) [13]. The framework classified accuracy errors into major and minor errors, and levels of accessibility were classified into direct, indirect and inaccessible. Definitions of each of these classifications can be found in the “Error Classification framework” subsection below.

Main study

Changes following the pilot

Following the pilot, it was agreed that the main analysis could be performed with only some minor changes to the classification framework. First, an additional classification was included into the accessibility framework, which was termed as ‘dead-end’ referencing. Dead-end referencing is defined as when the referenced statement brings the reader to a source which fails to provide the required evidence to support the referenced statement. These references essentially mislead readers into a ‘dead-end’ in terms of finding supporting evidence required to substantiate the claims made. Dead-end referencing differs from indirect referencing, where the reference, despite not substantiating the claim itself, does provide access to the primary evidence source through further references that ultimately substantiates the claims made. In rating accessibility errors, previous studies had mainly focused on indirect referencing or when referenced sources could not be accessed altogether (e.g. reference inaccessible due to a broken web link, a fabricated source, etc.) The addition of ‘dead-end’ referencing was a result of the pilot observation that the ability to access the referenced source was not sufficient to guarantee the provision of relevant and required supporting evidence to substantiate the claims made. The second minor change included allowing the criteria for ‘direct’ referencing to be more lenient than in previous studies. Specifically, direct referencing was not only limited to references purely directed to original scientific articles but also extended to other evidence sources such as governmental surveys, statistical reports and independent research reports by various organisations. This was a result of the pilot observation that policy documents use a substantially wider array of sources as evidence than scientific articles in the medical field. Reports published by independent research groups or the government itself could be rigorous methodologically even though they are not published in peer-reviewed journals and may be the only source of evidence for a given question.

Search strategy and inclusion criteria

A further eight (n = 10 in total) mental health-relevant policy documents were used in addition to the two analysed in the pilot round. The search strategy for the main study was the same as the pilot. The same inclusion and exclusion criteria were used to identify relevant policy documents. Documents were screened starting from the most recently published, and the search was terminated once eight policy documents had been identified. This meant that the ten documents were the ten most recent mental health policy documents that met the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Data extraction and analysis

236 factual statements were selected by reviewers who independently assessed each document. Up to 25 statements were sampled from each of the 10 policy documents. However, some documents featured fewer than 25 eligible statements; therefore, the final number of referenced statements extracted for analysis amounted to 235 statements rather than 250 statements.

Two reviewers were involved in the statement selection and error checking process. The first reviewer (AH) selected three quarters of the statements and error checked all statements. The second reviewer (AT) selected a quarter of the statements and independently error checked a third of the full sample of chosen statements. During the pilot round, the statements selected were cross-checked to ensure consistency of statement selection between both reviewers. The data were recorded by both reviewers using an extraction table developed specifically for the study. Initially, reviewers were fully blinded to the decisions made by each other. Decisions of the classifications for statements of all ten documents were then cross-checked and finalised after a discussion between reviewers where independent ratings were compared and discrepancies resolved.

Error classification framework

For specific examples, Table 2 provides a sample of statements illustrating each subtype of inaccuracy as described, drawn from the overall pool of accuracy errors found in the policy documents used in this study. Table 3 provides a sample of statements of each subtype of inaccessibility as described above, drawn from the overall pool of accessibility issues found in the policy documents used in this study.

Analysis

A count of minor and major accuracy and accessibility errors based on classifications defined in Table 1 were recorded on a summary table. The percentage of fully accurate referenced statements was calculated by subtracting statements with major and minor errors from the overall number of statements assessed. The percentage of directly accessible references was calculated by subtracting the percentage of those that were indirectly referenced, dead-end references, inaccessible as well as those with major errors from the overall number of statements extracted. Major errors were subtracted from the total number accessible statements as the question of accessibility was thought to be irrelevant for statements that were markedly unrelated to, unsubstantiated by or contradicted the referenced source.

Results

The ten policy documents selected and used for the main analysis can be found in Table 4. The majority of these documents were published by the Department of Health and Social Care for England, or by, Public Health England or NHS England, which are associated ‘arms-length bodies’ responsible for formulating and implementing policy [15]. All eligible policy documents were labelled as a ‘guidance’ on the governmental website under the ‘Policy and guidance’ subsection. 22–25 statements were selected from each document. In total, 49 statements were identified in the pilot and a further 187 for the main analysis (n = 236 overall). The statements used in the pilot round were included in the main analysis as only minor modifications were made to the assessment framework. It is important to note that a substantial amount of policy documents was immediately screened out as ineligible as they contained no references at all.

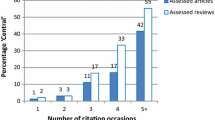

Of the 236 statements, 141 (59.7%) statements contained no errors in accuracy, 45 (19.1%) contained major errors and 50 (21.2%) contained minor errors (see Fig. 1). Out of the 236 referenced statements assessed, 126 statements (53.4%) contained references that directly provided access to the empirical evidence required to support the statement. 36 (15.3%) contained indirect references, 18 (7.6%) provided ‘dead-end’ references, and 11 (4.7%) were completely inaccessible (see Fig. 2). The majority of the minor accuracy errors were attributed to the overgeneralisation from the referenced source (21/236) and reporting errors of the quantitative results of the original studies (17/236), whereas the majority of major accuracy errors were related to the referenced statement unsubstantiated by its referenced source (35/236). Common citations that provided ‘dead-end’ access to evidence for factual statements included referencing online information leaflets, other policy documents, fact sheets, web pages and opinion articles. A summary table of the prevalence of each accuracy and accessibility issue found is shown in Table 5. For an anonymised summary table of accessibility and accuracy issue counts for each policy document, see Appendix 1. For a full extraction table of all statements assessed, see Appendix 2.

Discussion

There is a growing interest in the use of evidence in policy documents in England as well as internationally. To our knowledge, this is the first systematic investigation of referencing accuracy and accessibility in mental health policy documents within the United Kingdom or internationally. The pilot demonstrated that it was feasible to adapt an established framework previously used to assess referencing in scientific papers in a way that was informative, straightforward, and allowed the objectives of the current study to be quickly addressed. As discussed previously, the framework was based on a structure frequently used to assess referencing in peer-reviewed articles in the medical literature, therefore, it is likely to have covered the core aspects of referencing accessibility and accuracy that were considered important in the past. With slightly over half of the referenced statements assessed qualifying as fully accessible and accurate, there is, without a doubt, room for improvement for these two components of referencing quality. In comparison with the estimation of accuracy and accessibility errors in the medical literature as most recently examined by Mogull (2017) [13], the level of accuracy and accessibility in mental health policy documents appears at glance to be substantially lower. Whereas in the former, the overall error rate the author estimated was 14.5% and the rate of indirect referencing was approximately 10.4%, the overall accuracy error rate in the present study was 40.3% and the rate of indirect references was approximately 15.3%. However, comparisons of error prevalence to previous studies should be made with caution due to the differences in the nature of the content examined as well as the modifications in the methodology. Qualitatively, although the majority of references were directed towards original empirical research, what constituted citable evidence in policy documents was evidently more varied and less aligned with the hierarchy of evidence that is prioritised in evidence-based practice and NICE guidelines.

There is ongoing interest in better integrating evidence at different stages of the policy making process. Improving issues relating to accuracy and accessibility to evidence that permeate high-profile documents can be divided into two processes that are integral to one another. The first is the pursuit of a systematic method that quantifies such errors in a relatively simple and rapid manner. This has been the focus of the current study. The second is to implement standards and regulations which enforce such an assessment—a process that involves discussions beyond the scope of the current investigation. It is only when such assessments are prompted and regulated bureaucratically can one be assured that the representation and accessibility of evidence in policy documents are maintained at the highest of standards. To our knowledge, there is no guidance or regulation on referencing in policy documents in the United Kingdom or internationally. In concordance with Sense about Science (2016) [11], a set of standards for referencing practice should be widely implemented to serve as a reassurance that policy documents uphold a high standard of academic integrity and accountability. Such standards for responsible publications can be based off existing international standards for academic research publications, similar to that developed at the second World Conference on Research Integrity [17].

The act of referencing does not simply serve the function of providing readers with the evidence base behind the claims made. Instead, citations are alluring as they allow a piece of writing to differentiate itself from more subjective, opinionated and journalistic work. It may propel readers to trust that the stance made on a particular subject is rooted in empirical evidence and a result of academically rigorous understanding. In short, references give its content a particular authority. One may feel more confident in statements with a reference in comparison to statements without such companions, even without checking it [19]. Continuing to cite without ensuring accessibility and accuracy of these references can tarnish the quality of the document itself and unintentionally mislead organisations and professionals who automatically give into the façade of objectivity. Without a doubt, issues surrounding evidence-based policy making is complex, non-linear issue. This may require the right education and collaborations with academics to facilitate writers’ ability to extract primary findings from research and to implement these into policy [20]. However, regardless of the complexity of evidence-based writing, ensuring referencing is of the highest of standards is a simple first step and a sign of commitment to evidence-based policy making. It, at the very least, showcases diligence in using and communicating evidence in policy documents. If evidence-based policy is—at least conceptually—an extension of evidence-based practice [14], then there is the potential to extrapolate apply these methods to gain an insight into equivalent issues in mental health-relevant UK policy documents, providing a basis where such analyses have yet to be undertaken properly and seriously. Of note, to our knowledge, no research paper has previously reported on this in any health policy context.

Limitations

There are some limitations to the present study. First, our search strategy resulted in a wide range of documents, the majority of which were irrelevant to our study; examples include statements and speeches made by politicians, press releases, green papers, and more. In what we defined as a ‘policy document’, we included documents labelled in various ways (e.g. ‘framework’, ‘guidance’, ‘action’, ‘strategy’, ‘commissioning guide’, etc.). There was also a high proportion of policy documents that were immediately identified as ineligible for the study, despite containing a similar amount of factual statements as eligible documents. We noticed that a considerable number of these documents were ineligible, because they either (i) exclusively cited other policy documents, (ii) referenced only a handful of sources, or (iii) provided no references at all. This arguably limits the representativeness of the present study.

Second, the method by which statements were sampled by reviewers arguably introduced subjective bias. Alternative methods may include purposive sampling using sampling frames to achieve maximum breadth and variation of referenced statements, assessing all the factual statements in a given document, or sampling statements using a computerised randomisation process. However, given the length of many policy documents, and the resource available to conduct this study, these alternatives were deemed impractical for the present study. The primary focus of the present work was to pilot a method of appraising reference accuracy in policy documentation and to obtain preliminary results from that work. This was achieved, however, more laborious sampling methods may have improved the representativeness of selected statements. However, as up to 25 statements were included from each policy document, a fairly high proportion of eligible statements are likely to have been included. Indeed, some policy documents did not include 25 statements that met inclusion criteria. Nevertheless, an aim for future research could be to refine the method by which statements are sampled.

Third, even though significant effort was made to minimise reviewer subjectivity in the evaluation of statement quality, such as by thoroughly setting out specific parameters for the error classifications to standardise judgments and the involvement of a secondary, independent reviewer, decisions may still differ between reviewers. While similar caveats exist in some areas of current systematic review methodology, such as in the appraisal of the risk of bias, more could perhaps be done in the future to assess the inter-rater reliability of these types of classification frameworks.

Fourth, although the framework used in the present study was simple and straightforward to use, realistically, it can only be used by individuals who can freely access scientific journals. The ability to attain the original sources required to spot check the accuracy and accessibility of cited facts would otherwise often be limited by pay walls. Further, unlike the Evidence Transparency Framework [18] that was designed to be understandable and useable regardless of the level of expertise of the reader, the current framework may require reviewers to have a sufficient background in research methodology to understand scientific articles and from there to identify and classify accuracy errors correctly.

Lastly, as the first investigation of this kind, we made a pragmatic decision to limit our scope to policy documents from the country we are based in. Having included only documents published in England, the findings of the current study may only apply within this area. Therefore, the social, political and cultural context of our study should be considered before applying findings to other countries. Future research into policy documents in other countries would most certainly be both interesting and important.

Conclusion

In light of the findings of the current study, referencing accuracy and accessibility are two components of referencing quality that warrant further attention in mental health policy documents. In this investigation in the England, it appears that referenced statements are error prone or are not referenced at all. As such, the utility of the framework used in the current study is high and can form a core part in the maintenance of integrity in policy documents, with investigations in other countries that aspire to evidence-making policy also warranted. We believe that it is a small yet essential step towards meeting the larger ambitions of the evidence-based policy movement. We hope this paper will prompt further studies of referencing quality in mental health policy documents, as well as provide a benchmark for studies seeking to improve the quality of referencing in other policy documents.

Change history

11 November 2019

In the original publication of the article there was an error in the results section of the abstract. The first sentence should have read.

References

Young K, Ashby D, Boaz A, Grayson L (2002) Social science and the evidence-based policy movement. Soc Policy Soc 1:03

Rutter J, Gold J (2015) Show your workings: assessing how government uses evidence to make policy. Institute for government. https://www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/sites/default/files/publications/4545%20IFG%20-%20Showing%20your%20workings%20v8b.pdf. Accessed 26 Feb 2019

Lawson LA, Fosker R (1999) Accuracy of references in psychiatric literature: a survey of three journals. Psychiatr Bull 23(4):221–224

Gosling CM, Cameron M, Gibbons PF (2004) Referencing and quotation accuracy in four manual therapy journals. Manual Ther 9(1):36–40

Warren KJ, Bhatia N, Teh W, Fleming M, Lange M (1997) Reference and quotation accuracy in the major and minor infectious diseases journals. In 3rd International Congress on Peer Review in Biomedical Publication, pp. 18–20

Eichorn P, Yankauer A (1987) Do authors check their references? A survey of accuracy of references in three public health journals. Am J Public Health 77(8):1011–1012

Hinchcliff KW, Bruce NJ, Powers JD, Kipp ML (1993) Accuracy of references and quotations in veterinary journals. J Am Vet Med Assoc 202(3):397–400

Schulmeister L (1998) Quotation and reference accuracy of three nursing journals. J Nurs Scholarsh 30(2):143–146

Greenberg SA (2009) How citation distortions create unfounded authority: analysis of a citation network. BMJ 339:b2680

Simkin MV, Roychowdhury VP (2007) A mathematical theory of citing. J Am Soc Inform Sci Technol 58(11):1661–1673

Sense about Science (2016) Transparency of Evidence: an assessment of government policy proposals May 2015 to May 2016 http://senseaboutscience.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/SaS-Transparency-of-Evidence-2016-Nov.pdf. Accessed 26 Feb 2019

Sense about Science (2018) Transparency of evidence: an assessment of government policy proposals July 2016 to July 2017. http://senseaboutscience.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/Transparency-of-evidence-spotcheck.pdf. Accessed 26 Feb 2019

Mogull SA (2017) Accuracy of cited “facts” in medical research articles: a review of study methodology and recalculation of quotation error rate. PLoS One 12(9):e0184727

Oliver K, Pearce W (2017) Three lessons from evidence-based medicine and policy: increase transparency, balance inputs and understand power. Palgrave Commun 3(1):43

National Audit Office (2016) Departments’ oversight of arm’s length bodies: a comparative study. https://www.nao.org.uk/report/departments-oversight-of-arms-length-bodies-a-comparative-study/. Accessed 26 Feb 2019

Jergas H, Baethge C (2015) Quotation accuracy in medical journal articles—a systematic review and meta-analysis. PeerJ 3:e1364

Wager E, Kleinert S (2016) Responsible research publication: international standards for authors. Promot Res Integr Global Environ 22:309–316

Institute for Government (2015) Evidence Transparency Framework. https://www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/sites/default/files/publications/4545%20IFG%20-%20Evidence%20Trans%20framework%20v6.pdf. Accessed 26 Feb 2019

Mertens S, Baethge C (2011) The virtues of correct citation: careful referencing is important but is often neglected/even in peer reviewed articles. Deutsches Ärzteblatt Int 108(33):550

Head BW (2010) Reconsidering evidence-based policy: key issues and challenges. Policy Soc 29(2):77–94

Acknowledgements

SJ and LSR are partly supported by the NIHR Mental Health Policy Research Unit.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Hui, A., Rains, L.S., Todd, A. et al. The accuracy and accessibility of cited evidence: a study examining mental health policy documents. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 55, 111–121 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-019-01786-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-019-01786-8