Abstract

Background

Early social and cognitive alterations in psychotic disorder, associated with familial liability and environmental exposures, may contribute to lower than expected educational achievement. The aims of the present study were to investigate (1) how differences in educational level between parents and their children vary across patients, their healthy siblings, and healthy controls (effect familial liability), and across two environmental risk factors for psychotic disorder: childhood trauma and childhood urban exposure (effect environment) and (2) to what degree the association between familial liability and educational differential was moderated by the environmental exposures.

Methods

Patients with a diagnosis of non-affective psychotic disorder (n = 629), 552 non-psychotic siblings and 326 healthy controls from the Netherlands and Belgium were studied. Participants reported their highest level of education and that of their parents. Childhood trauma was assessed with the Dutch version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire-Short Form. Urban exposure, expressed as population density, was rated across five levels.

Results

Overall, participants had a higher level of education than their parents. This difference was significantly reduced in the patient group, and the healthy siblings displayed intergenerational differences that were in between those of controls and patients. Higher levels of childhood urban exposure were also associated with a smaller intergenerational educational differential. There was no evidence for differential sensitivity to childhood trauma and childhood urbanicity across the three groups.

Conclusion

Intergenerational difference in educational achievements is decreased in patients with psychotic disorder and to a lesser extent in siblings of patients with psychotic disorder, and across higher levels of childhood urban exposure. More research is required to better understand the dynamics between early social and cognitive alterations in those at risk in relation to progress through the educational system and to understand the interaction between urban environment and educational outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Cognitive alterations are core features during all phases of psychotic disorder, including premorbid state, onset, and longitudinal course [1–5]. Cognitive alterations are associated with disabilities in everyday functioning [6]. The origin of cognitive alterations remains unclear, and may be confounded by motivational factors [7]. Nevertheless, as cognitive alterations are present in the premorbid phases of psychosis [4, 5] and unaffected siblings show impaired cognitive functioning [8–10], developmental and genetic origins are likely.

Other substantiations for a developmental route come from a large Swedish birth cohort which showed lower level of school performance was associated with the development of schizophrenia [11]. Early cognitive alterations may thus contribute to alterations in educational achievement. However, other studies on scholastic achievement did not find such a clear association with the development of psychotic disorder. Not being in the expected class at age 14 predicted future hospital-treated disorders, but not specifically psychotic disorder [12] and poor school performance in art and handicrafts, but not academic performance was a risk factor for schizophrenia [13].

Investigating cognitive alterations in relation to educational achievement is important as it may shed light on the early origins of social disability associated with cognitive alterations in psychotic disorder. A range of non-cognitive factors are known to influence school performance and educational outcomes, socioeconomic status [14], and obstetric/perinatal complications [15–17] being well-known examples.

Few studies [1, 11] on cognitive or scholastic performance in psychotic disorder included data on educational performance of the parents. Parental educational level is required in order to interpret actual educational level in relation to the expected educational level as predicted by parental education [1]. No studies on educational performance included the unaffected siblings of patients with psychotic disorder, which similarly will increase the accuracy of interpreting actual versus expected educational level. As far as we are aware, it remains unknown whether unaffected siblings of patients with a psychotic disorder perform below the expected level in school. Furthermore, cognitive functioning in psychotic disorder is associated with sociodemographic factors, such as childhood trauma and stress [3] and urban habitat [18]. Stress and altered functioning of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis, with harmful effects of stress and glucocorticoids on the brain is a possible explanation for this association [19]. As these factors may thus impact the association between cognitive alterations and educational achievement, inclusion of these in the analyses may be profitable.

The aim of the present study was to investigate (1) how differences in educational level between parents and their children vary across patients, their healthy siblings and healthy controls (effect familial liability), and across two environmental risk factors for psychotic disorder: childhood trauma and childhood urban exposure (effect environment) and (2) to what degree the association between familial liability and educational differential was moderated by the environmental exposures (childhood trauma and childhood urbanicity). It was hypothesized that patients had lower levels of education compared to their parents, than controls in comparison with their parents, and that the healthy siblings were in between the controls and the patients in this respect. Childhood urban exposure and childhood trauma were hypothesized to negatively impact the educational differential. Thus, it was expected that in the patient group, and to a lesser degree in the sibling group, both environmental exposures would negatively influence the educational difference.

Materials and methods

Participants

Data pertain to baseline measures of an ongoing multisite, longitudinal, naturalistic cohort study, the Dutch national Genetic Risk and Outcome in Psychosis (GROUP) project [20]. Because data on parental education were not collected for the region Groningen, this region was excluded from the analysis. Participants younger than 23 years of age were also excluded from the analysis, because it is less likely that they would have completed their educational potential [21]. The sample thus consisted of 629 patients diagnosed with a non-affective psychotic disorder, 552 of their siblings, and 326 unrelated healthy control subjects from the general population from the Netherlands and Belgium. Controls were selected through a system of random mailings to addresses in the catchment areas of the cases. Exclusion criteria for controls were lifetime psychotic disorder and having a first degree relative with a lifetime psychotic disorder. The full selection procedure and in- and exclusion criteria have been described previously [20].

The study was approved centrally by the Ethical Review Board of the University Medical Centre Utrecht. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects after they (1) read a document with detailed information about the nature and possible consequences of the study; (2) had verbally discussed any possible concerns with the researcher; and (3) had provided clear indication that they had understood the procedure. In the Netherlands, adult patients with mental illness are considered participating citizens who have the right to make independent informed decisions including the autonomous decision to participate in research; therefore, consent of relatives was not sought.

Education

In the Netherlands, most schools are state schools which are organized in primary, secondary, and tertiary education tiers. From 4 until 12 years of age, all children receive primary education. After 12 years, children attend one of four levels of secondary education (low, intermediate, high preparatory vocational, and pre-university); each level requires increasing intellectual and scholastic abilities. After passing the exams in secondary education, there are three possible levels of tertiary education (intermediate professional education, higher professional education, and university).

Participants were asked to report their highest level of education and that of their parents, also if not completed. This conservative strategy was chosen as subjects with psychotic disorder are less likely to complete their education because of the emergence of psychotic symptoms [22] (mean age of onset was 25.0 in this study sample with a standard deviation of 6.5). Education was classified across 7 categories: Level 1: no education; Level 2: primary school; Level 3: lower secondary education; Level 4: intermediate professional education; Level 5: higher secondary education; Level 6: bachelor degree or equivalent (higher professional education); and Level 7: university (master degree).

Childhood trauma

Childhood trauma was assessed with the Dutch version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire Short Form (CTQ) [23]. The short CTQ consists of 25 items rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = never true to 5 = very often true) enquiring about traumatic experiences in childhood. Five types of childhood maltreatment were assessed: emotional, physical and sexual abuse, and emotional and physical neglect, with five questions covering each type of trauma. The mean score for all 25 items was divided in tertiles (low, medium, and high childhood trauma). The latter was used as the primary variable reflecting childhood trauma in the analyses. CTQ data were missing for 353 persons (23 % missing data).

Level of childhood urbanicity

A historical population density record was generated for each municipality from 1930 onwards using historical data from Statistics Netherlands and the equivalent database in Belgium [24, 25]. When data was not available, missing data were calculated by linear extrapolation between two subsequent time-points. When historical names of municipalities disappeared from historical records (e.g., due to city mergers) the available data from the agglomerate city were used. Subjects were asked to describe where they had lived at birth, between ages 0 and 4; between 5 and 9; 10–14; 15–19; 20–39; 40–59 years; and 60+ up to the actual age. This resulted in a number of records for each subject, containing locations by age period. For each of these records, we computed the average population density (by square kilometer, excluding water) of the municipality for the matching periods. Average population density over the period was categorized in accordance with the Dutch CBS urbanicity rating (1 ≤ 500/km2; 2 = 500–000/km2; 3 = 1000–1500/km2; 4 = 1500–2500/km2; 5 = 2500+/km2). The periods 0–4, 5–9, and 10–14 years were collapsed to produce average urbanicity exposure between 0 and 14 years, rounded to the nearest whole number. Urbanicity data was missing for 132 persons (9 % missing data).

Statistical analyses

All analyses were performed using Stata 12 [26]. The main outcome variable was difference in educational level between the subject and highest level of education among the two parents (difference in education level (edu-dif) was calculated as the highest parental education—education subject).

In order to test whether edu-dif varied across patients with psychotic disorder, their healthy siblings and healthy controls and also across categories of childhood trauma and childhood urbanicity, multilevel linear regression models were fitted with edu-dif as the dependent variable and group status (patient, sibling, or control), childhood trauma (low, medium, and high childhood trauma), and childhood urbanicity (5 levels of childhood urbanicity) as independent variables. Multilevel regression analysis was used to account for clustering of repeated measures within families, using the Stata XTMIXED command, with family ID modeled as the macro level. The regression coefficient (B) represents the effect size of the predictors and can be interpreted as the estimates in equivalent unilevel linear regression analysis. All independent variables were entered together as categorical variables recoded into dummy variables (model 1). In a separate analysis, independent variables were entered together as continuous variables in order to obtain linear associations (model 2). Age, sex, and ethnicity were added as possible confounders. Age was added as confounder given that education, as well as access to education, may change over time. For the same reason, sex and ethnicity were added as (possible) confounders.

In order to study to what degree associations between edu-dif on the one hand and childhood trauma and childhood urbanicity on the other varied between patients, siblings, and controls, two-way interactions between childhood trauma and group and between childhood urbanicity and group were added to the model of edu-dif separately (childhood trauma and childhood urbanicity are both variables with n categories, entered as a continuous variable and as n-1 dummy variables). In the case of significant interaction, stratified effect sizes were calculated by linear combination of the effects from the model containing the main effect and the interaction term using the Stata MARGINS routine.

Results

Participants

The total sample consisted of 629 patients with a diagnosis of non-affective psychotic disorder, 552 of their siblings and 326 control subjects. Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the final sample are summarized in Table 1. The patients were younger and more often were male. The percentage of non-whites was higher in the patient group and the overall CTQ score and childhood urbanicity score were higher in the patient group. Patients and siblings had a significantly lower level of education than controls (controls: mean 4.42, SD 1.31; siblings: mean 4.24, SD 1.43; patients: mean 3.76, SD 1.48; controls compared to patients: p < 0.001; controls compared to siblings: p = 0.027). Parental education was significantly higher in the siblings compared to controls (controls: mean 3.28, SD 1.52; siblings: mean 3.81, SD 1.71, controls compared to siblings p = 0.004), and similarly directionally higher in the patients (patients: mean 3.58, SD 1.77, controls compared to patients p = 0.064).

Educational difference and main effects of group, childhood trauma, and childhood urbanicity

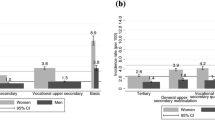

In all three groups, edu-dif had a negative value (Table 2; Fig. 1), indicating that participants had a higher level of education than their parents. There was a significant association between group (linear trend) and edu-dif (B = 0.36, p < 0.001). Edu-dif was significantly less negative in the patient group than in the control group (B = 0.77, p < 0.001), while siblings were in between the controls and the patients (B = 0.49, p = 0.001). The effect of maternal and paternal education was similar (maternal education: B linear trend = 0.36, p < 0.001, patients: B = 0.77, p < 0.001, siblings: B = 0.43, p = 0.003; paternal education: B linear trend = 0.34, p < 0.001, patients: B = 0.77, p < 0.001, siblings: B = 0.54, p < 0.001).

Edu-dif was not associated with childhood trauma (B linear trend = 0.07, p = 0.279; Table 2). Childhood urbanicity was significantly associated with edu-dif (B linear trend = 0.11, p = 0.002), the main contrast being between urbanicity level 1 and the other 4 categories (Table 2; Fig. 2).

Interaction between group and childhood trauma or childhood urbanicity

There was no evidence that associations between edu-dif and environmental risks differed by group (Table 3).

Discussion

Educational difference (edu-dif) between subjects and their parents was studied in groups of psychotic patients, healthy siblings, and healthy controls. Overall, participants had a higher level of education than their parents. This difference was significantly less in the patient group and the healthy siblings were in between the controls and the patients. Further it was tested whether edu-dif was influenced by childhood trauma and childhood urbanicity, and if this was different for patients, siblings, and controls. Only childhood urban exposure had a significant influence on edu-dif: higher levels of childhood urban exposure were associated with a smaller increase in educational level. There was no evidence that this association differed for patients, siblings, or controls.

In all three groups, participants had a higher level of education than their parents. A reasonable explanation for this is development of education and growing availability of education over time. Patients and siblings had a smaller increase in educational level than the healthy controls. This is in line with previous research indicating early cognitive alterations in psychotic disorder [4, 5] and also with research on alterations in cognitive functioning in first-degree relatives of patients with psychotic disorder [8–10, 27]. Previous research on scholastic achievements in psychotic disorder is not consistent [28]. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to include siblings, thus shedding light on possible mediation by familial factors including genetic factors.

Our findings could be explained by several hypothesis. One plausible explanation is that early alterations in cognition, in patients and in siblings, may lead to problems in school functioning and eventually to lower levels of education. A second explanation is that altered social cognition, a specific part of cognitive functioning, that is not only impaired in psychotic disorder [29] but also in persons at genetic and clinical high risk for psychosis [30–32], elevates stress and lowers school performance. A third explanation is that the siblings of patients with a psychotic disorder receive less parental attention and guidance through their school development, as a negative consequence of the worries and attention focussed on the (pre)psychotic sib.

We did not find childhood trauma to influence intergenerational educational differential, in contrast with existing literature. Childhood trauma is associated with lower academic performance [33, 34], adverse effects on educational attainment [35], and academic delay [34]. Boden and colleagues [14] also found that physical and sexual abuse negatively affected educational achievements, but this was largely explained by social, family, and individual factors, after taking parental and maternal education into account. In this study, educational level was assessed relative to parental education, which could explain why there was no significant difference.

To our knowledge, there are no other studies on childhood urban exposure and scholastic achievements. However, factors associated with the urban environment and school performance have been examined previously and are in line with our results: urban noise exposure has a negative effect on school performance [36] and lower perceived safety of schools and neighborhoods deteriorates school performance [37]. Another explanation is the disappearance of small village schools and the subsequent emergence of larger schools with more pupils [38]. For pupils, such a larger scaled social study environment may have negative effects on school performance.

Childhood urbanicity and childhood trauma were not differentially associated with educational differences across psychotic patients, siblings, and in controls. This makes it unlikely that childhood trauma and childhood urbanicity influence the effect of group on educational difference, in a positive or negative way.

Methodological considerations

Some limitations need to be addressed. The cross-sectional nature of the current data makes it impossible to establish a causal relationship between group status, childhood trauma, or childhood urbanicity and edu-dif; this was not the purpose of the study. Second, highest level of started education was studied, regardless of whether or not this was completed. This conservative approach was chosen because patients with psychotic disorder are less likely to complete education after the onset of psychotic symptoms [22]. Thus, studying completed education is more likely to measure the effect of psychotic symptoms, and not of early cognitive alterations, on educational achievement. Another approach could have been to compare grades in for example, primary education; however, grading systems may have changed over time and not all schools may use the same grading system, making this an inaccurate measure. Further, not all factors that could possibly affect school performance were taken into account, for example, family income and other non-educational factors associated with socioeconomic status, or obstetric and perinatal complications. However, school attendance in the Netherlands is not dependent on income as there is universal-free schooling. Fourth, the higher level of parental education for the siblings and at trend-level for the patients may have been the result of underlying selections, which could have influenced our results. However, the regression coefficients for the difference in parental education are smaller than the regression coefficients of edu-dif, which makes it unlikely that possible selection is the only explanation of the observed difference in edu-dif. Finally, the participants grew up in the Netherlands and Belgium which can be described as relatively safe and developed countries; in other counties, urban–rural discrepancies may be more prominent.

Conclusion

Patients with psychotic disorder, and to a lesser extent their healthy siblings, had a smaller increase in educational level compared with their parents than healthy controls. Although these group differences cannot be used to identify groups at high risk, it does provide a general perspective in thinking about intergenerational processes in educational achievement in the context of risk for psychosis. More work is required to better understand the dynamics between early social and cognitive alterations in those at risk in relation to progress through the educational system. Higher levels of childhood urbanicity were also associated with a smaller increase in educational level. As more people are residing in urbanized areas [39], more work is required to understand the interaction between urban environment and educational outcomes including school size, class size, level of individual educational support, and class dynamics.

References

Keefe RS, Eesley CE, Poe MP (2005) Defining a cognitive function decrement in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry 57(6):688–691. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.01.003

Schaefer J, Giangrande E, Weinberger DR, Dickinson D (2013) The global cognitive impairment in schizophrenia: consistent over decades and around the world. Schizophr Res 150(1):42–50. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2013.07.009

Aas M, Dazzan P, Mondelli V, Melle I, Murray RM, Pariante CM (2014) A systematic review of cognitive function in first-episode psychosis, including a discussion on childhood trauma, stress, and inflammation. Front Psychiatry 4:182. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2013.00182

Reichenberg A, Caspi A, Harrington H, Houts R, Keefe RS, Murray RM, Poulton R, Moffitt TE (2010) Static and dynamic cognitive deficits in childhood preceding adult schizophrenia: a 30-year study. Am J Psychiatry 167(2):160–169. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09040574

Keefe RS (2014) The longitudinal course of cognitive impairment in schizophrenia: an examination of data from premorbid through posttreatment phases of illness. J Clin Psychiatry 75(Suppl 2):8–13. doi:10.4088/JCP.13065su1.02

Green MF, Kern RS, Heaton RK (2004) Longitudinal studies of cognition and functional outcome in schizophrenia: implications for MATRICS. Schizophr Res 72(1):41–51. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2004.09.009

Fervaha G, Zakzanis KK, Foussias G, Graff-Guerrero A, Agid O, Remington G (2014) Motivational deficits and cognitive test performance in schizophrenia. JAMA Psychiatry 71(9):1058–1065. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.1105

McIntosh AM, Harrison LK, Forrester K, Lawrie SM, Johnstone EC (2005) Neuropsychological impairments in people with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder and their unaffected relatives. Br J Psychiatry J Ment Sci 186:378–385. doi:10.1192/bjp.186.5.378

Cannon TD, Huttunen MO, Lonnqvist J, Tuulio-Henriksson A, Pirkola T, Glahn D, Finkelstein J, Hietanen M, Kaprio J, Koskenvuo M (2000) The inheritance of neuropsychological dysfunction in twins discordant for schizophrenia. Am J Hum Genet 67(2):369–382. doi:10.1086/303006

Hughes C, Kumari V, Das M, Zachariah E, Ettinger U, Sumich A, Sharma T (2005) Cognitive functioning in siblings discordant for schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand 111(3):185–192. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2004.00392.x

MacCabe JH, Lambe MP, Cnattingius S, Torrang A, Bjork C, Sham PC, David AS, Murray RM, Hultman CM (2008) Scholastic achievement at age 16 and risk of schizophrenia and other psychoses: a national cohort study. Psychol Med 38(8):1133–1140. doi:10.1017/S0033291707002048

Isohanni I, Jarvelin MR, Nieminen P, Jones P, Rantakallio P, Jokelainen J, Isohanni M (1998) School performance as a predictor of psychiatric hospitalization in adult life. A 28-year follow-up in the Northern Finland 1966 Birth Cohort. Psychol Med 28(4):967–974

Cannon M, Jones P, Huttunen MO, Tanskanen A, Huttunen T, Rabe-Hesketh S, Murray RM (1999) School performance in Finnish children and later development of schizophrenia: a population-based longitudinal study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 56(5):457–463

Boden JM, Horwood LJ, Fergusson DM (2007) Exposure to childhood sexual and physical abuse and subsequent educational achievement outcomes. Child Abuse Negl 31(10):1101–1114. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.03.022

Arpi E, Ferrari F (2013) Preterm birth and behaviour problems in infants and preschool-age children: a review of the recent literature. Dev Med Child Neurol 55(9):788–796. doi:10.1111/dmcn.12142

Hadders-Algra M, Huisjes HJ, Touwen BC (1988) Perinatal risk factors and minor neurological dysfunction: significance for behaviour and school achievement at nine years. Dev Med Child Neurol 30(4):482–491

Hadders-Algra M, Huisjes HJ, Touwen BC (1988) Perinatal correlates of major and minor neurological dysfunction at school age: a multivariate analysis. Dev Med Child Neurol 30(4):472–481

Talreja BT, Shah S, Kataria L (2013) Cognitive function in schizophrenia and its association with socio-demographics factors. Ind Psychiatry J 22(1):47–53. doi:10.4103/0972-6748.123619

Sapolsky RM, Krey LC, McEwen BS (1986) The neuroendocrinology of stress and aging: the glucocorticoid cascade hypothesis. Endocr Rev 7(3):284–301. doi:10.1210/edrv-7-3-284

Genetic Risk Outcome in Psychosis (GROUP) investigators (2011) Evidence that familial liability for psychosis is expressed as differential sensitivity to cannabis: an analysis of patient-sibling and sibling-control pairs. Arch General Psychiatry 68(2):138–147. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.132

Statistics Netherlands (2011) Jaarboek Onderwijs in Cijfers. Central Bureau of Statistics Publications, The Hague

Isohanni I, Jones PB, Jarvelin MR, Nieminen P, Rantakallio P, Jokelainen J, Croudace TJ, Isohanni M (2001) Educational consequences of mental disorders treated in hospital. A 31-year follow-up of the Northern Finland 1966 Birth Cohort. Psychol Med 31(2):339–349

Bernstein DP, Ahluvalia T, Pogge D, Handelsman L (1997) Validity of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire in an adolescent psychiatric population. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 36(3):340–348. doi:10.1097/00004583-199703000-00012

Statistics Netherlands (1993) Bevolking der Gemeenten van Nederland. Central Bureau of Statistics publications, The Hague

Venkatasubramanian G, Jayakumar PN, Keshavan MS, Gangadhar BN (2011) Schneiderian first rank symptoms and inferior parietal lobule cortical thickness in antipsychotic-naive schizophrenia. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 35(1):40–46. doi:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2010.07.023

StataCorp (2007) Stata Statistical Software. Release 10.0 edn. Stata Corporation, College Station

Cannon TD, Bearden CE, Hollister JM, Rosso IM, Sanchez LE, Hadley T (2000) Childhood cognitive functioning in schizophrenia patients and their unaffected siblings: a prospective cohort study. Schizophr Bull 26(2):379–393

Welham J, Isohanni M, Jones P, McGrath J (2009) The antecedents of schizophrenia: a review of birth cohort studies. Schizophr Bull 35(3):603–623. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbn084

Kohler CG, Walker JB, Martin EA, Healey KM, Moberg PJ (2010) Facial emotion perception in schizophrenia: a meta-analytic review. Schizophr Bull 36(5):1009–1019. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbn192

Kohler CG, Richard JA, Brensinger CM, Borgmann-Winter KE, Conroy CG, Moberg PJ, Gur RC, Gur RE, Calkins ME (2014) Facial emotion perception differs in young persons at genetic and clinical high-risk for psychosis. Psychiatry Res. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2014.01.023

Bediou B, Asri F, Brunelin J, Krolak-Salmon P, D’Amato T, Saoud M, Tazi I (2007) Emotion recognition and genetic vulnerability to schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry J Ment Sci 191:126–130. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.106.028829

Lavoie MA, Plana I, Bedard Lacroix J, Godmaire-Duhaime F, Jackson PL, Achim AM (2013) Social cognition in first-degree relatives of people with schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res 209(2):129–135. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2012.11.037

Holt MK, Finkelhor D, Kantor GK (2007) Multiple victimization experiences of urban elementary school students: associations with psychosocial functioning and academic performance. Child Abuse Negl 31(5):503–515. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.12.006

Kurtz PD, Gaudin JM Jr, Wodarski JS, Howing PT (1993) Maltreatment and the school-aged child: school performance consequences. Child Abuse Negl 17(5):581–589

Tanaka M, Georgiades K, Boyle MH, MacMillan HL (2014) Child maltreatment and educational attainment in young adulthood: results from the Ontario child health study. J Interpers Violence. doi:10.1177/0886260514533153

Pujol S, Levain JP, Houot H, Petit R, Berthillier M, Defrance J, Lardies J, Masselot C, Mauny F (2014) Association between ambient noise exposure and school performance of children living in an urban area: a cross-sectional population-based study. J Urban Health Bull N Y Acad Med 91(2):256–271. doi:10.1007/s11524-013-9843-6

Milam AJ, Furr-Holden CDM, Leaf PJ (2010) Perceived school and neighborhood safety, neighborhood violence and academic achievement in urban school children. Urban Rev 42:458–467

Statistics Netherlands (2012) Jaarboek onderwijs in cijfers 2012. Central Bureau of Statistics publications, The Hague

United Nations Population Fund (2011) State of world population 2011: people and possibilities in a world of 7 billion. United Nations Population Fund, New York

Conflict of interest

The infrastructure for the GROUP study is funded through the Geestkracht programme of the Dutch Health Research Council (ZON-MW, grant number 10-000-1001), and matching funds from participating pharmaceutical companies (Lundbeck, AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, Janssen Cilag) and universities, and mental health care organizations. This study was supported by the European Community’s Seventh Framework Program under Grant Agreement No. HEALTH-F2-2009-241909 (Project EU-GEI). The funding bodies had no role in the study design, collection, analysis or interpretation of the data, writing of the report, and the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Additional information

GROUP Investigators members are listed in the “Appendix”.

Appendix

Appendix

Genetic Risk and Outcome of Psychosis (GROUP) Investigators: Richard Bruggemana, Wiepke Cahnb, Lieuwe de Haanc, René Kahnb, Carin Meijerc, Inez Myin-Germeysd, Jim van Osd,e, Durk Wiersmaa

aUniversity Medical Center Groningen, Department of Psychiatry, University of Groningen, The Netherlands, bUniversity Medical Center Utrecht, Department of Psychiatry, Rudolf Magnus Institute of Neuroscience, The Netherlands, cAcademic Medical Centre University of Amsterdam, Department of Psychiatry, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, dMaastricht University Medical Centre, South Limburg Mental Health Research and Teaching Network, EURON, Maastricht, The Netherlands, eKing’s College London, King’s Health Partners, Department of Psychosis Studies, Institute of Psychiatry, London, United Kingdom.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Frissen, A., Lieverse, R., Marcelis, M. et al. Psychotic disorder and educational achievement: a family-based analysis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 50, 1511–1518 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-015-1082-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-015-1082-6