Abstract

Purpose

The aim of this study was to utilize bootstrapping to investigate the robustness of latent class trajectories and risk factors of depressive symptoms among mothers of children with epilepsy.

Methods

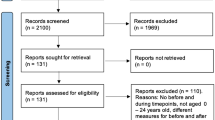

Data were obtained from a national prospective cohort study (2004–09) of children newly diagnosed with epilepsy and their families in Canada (n = 339). Latent classes of depressive symptom trajectories were modeled using a semi-parametric group-based trajectory modeling approach. Multinomial logistic regression identified risk factors predicting trajectory group membership.

Results

Four trajectories were identified: low stable, borderline, moderate increasing, and high decreasing. Goodness of fit, posterior probabilities, and parameter estimates obtained with bootstrapping were not significantly different from the original sample. Calculation of the root mean square error demonstrated minimal non-ignorable bias for three parameter estimates, which was subsequently removed with additional sampling. Risk factors identified were identical for the original sample and the bootstrap, and differences in odds ratios, as calculated with the method of variance estimation recovery, were not significant.

Conclusions

As examined using a bootstrapping procedure, group-based trajectory modeling offers a robust methodology to uncover potential heterogeneity in populations and identify high-risk individuals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In comparison to other models tested, the four-group model demonstrated the best fit based on the specified criteria, and had the highest probability of being the correct model. A three-group model had a BIC index of −4204.84 and −4197.17 posterior probabilities of group membership ranging from 0.82 to 0.93 and 0.81 to 0.93 for the original and bootstrap samples, respectively. A five-group model had a BIC index of −4188.88 and −4179.13 posterior probabilities of group membership ranging from 0.71 to 0.87 and 0.73 to 0.91, respectively.

References

Singer JD, Willett JB (2003) Applied longitudinal data analysis: modeling change and event occurrence. Oxford University Press, New York

Duncan TE, Duncan SC, Stryker LA (2006) An introduction to latent variable growth curve modeling, 2nd edn., Concepts, issues, and applicationsLawrence Erlbaum, Mahwah

Gump BB, Reihman J, Stewart P, Lonky E, Darvill T, Granger DA, Matthews KA (2009) Trajectories of maternal depressive symptoms over her child’s life span: relation to adrenocortical, cardiovascular, and emotional functioning in children. Dev Psychopathol 21:207–225

Cambron MJ, Acitelli LK, Steinberg L (2010) When friends make you blue: the role of friendship contingent self-esteem in predicting self-esteem and depressive symptoms. Per Soc Psychol Bull 36:384–397

Marmorstein NR (2010) Longitudinal associations between depressive symptoms and alcohol problems: the influence of comorbid delinquent behavior. Addict Behav 35:564–571

Ferro MA, Avison WR, Campbell MK, Speechley KN (2011) The impact of maternal depressive symptoms on health-related quality of life in children with epilepsy: a prospective study of family environment as mediators and moderators. Epilepsia 52:316–325

Weiss RE (2005) Modeling longitudinal data. Springer, New York

Nagin DS (2005) Group-based modeling of development. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Nagin DS, Tremblay RE (2005) What has been learned from group-based trajectory modeling? Examples from physical aggression and other problem behaviors. Ann Am Acad Pol Soc Sci 602:82–117

Nagin DS, Tremblay RE (2005) Further reflections on modeling and analyzing developmental trajectories: a response to Maughan and Raudenbush. Ann Am Acad Pol Soc Sci 602:145–154

Raudenbush SW (2005) How do we study “what happens next”? Ann Am Acad Pol Soc Sci 602:131–144

Raudenbush SW (2001) Comparing personal trajectories and drawing causal inferences from longitudinal data. Annu Rev Psychol 52:501–525

Altman DG, Royston P (2000) What do we mean by validating a prognostic model? Stat Med 19:453–473

Mazza JJ, Fleming CB, Abbott RD, Haggerty KP, Catalano RF (2010) Identifying trajectories of adolescents’ depressive phenomena: an examination of early risk factors. J Youth Adolesc 39:579–593

Wickrama T, Wickrama KA (2010) Heterogeneity in adolescent depressive symptom trajectories: implications for young adults’ risky lifestyle. J Adolesc Health 47:407–413

Buckingham-Howes S, Oberlander SE, Hurley KM, Fitzmaurice S, Black MM (2011) Trajectories of adolescent mother-grandmother psychological conflict during early parenting and children’s problem behaviors at age 7. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 40:445–455

Ferro MA, Avison WR, Campbell MK, Speechley KN (2011) Prevalence and trajectories of depressive symptoms in mothers of children with newly diagnosed epilepsy. Epilepsia 52:326–336

Steyerberg EW, Harrell FE Jr, Borsboom GJ, Eijkemans MJ, Vergouwe Y, Habbema JD (2001) Internal validation of predictive models: efficiency of some procedures for logistic regression analysis. J Clin Epidemiol 54:774–781

Efron B (1979) Bootstrap methods: another look at the jackknife. Ann Stat 7:1–26

Bickel P, Freedman DA (1984) Asymptotic normality and the bootstrap in stratified sampling. Ann Stat 12:470–482

Efron B, Tibshirani R (1986) Bootstrap methods for standard errors, confidence intervals, and other measures of statistical accuracy. Stat Sci 1:54–77

Parke J, Charles BG (2000) Factors affecting oral cyclosporin disposition after heart transplantation: bootstrap validation of a population pharmacokinetic model. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 56:481–487

Brunelli A, Rocco G (2006) Internal validation of risk models in lung resection surgery: bootstrap versus training-and-test sampling. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 131:1243–1247

Ferro MA, Speechley KN (2012) Examining clinically relevant levels of depressive symptoms in mothers following a diagnosis of epilepsy in their children: a prospective analysis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 47:1419–1428

Ferro MA, Avison WR, Campbell MK, Speechley KN (2010) Do depressive symptoms affect mothers’ reports of child outcomes in children with new-onset epilepsy? Qual Life Res 19:955–964

Radloff LS (1977) The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Measures 1:385–401

Sabaz M, Lawson JA, Cairns DR, Duchowny MS, Resnick TJ, Dean PM, Bye AM (2003) Validation of the quality of life in childhood epilepsy questionnaire in American epilepsy patients. Epilepsy Behav 4:680–691

Sabaz M, Cairns DR, Lawson JA, Nheu N, Bleasel AF, Bye AM (2000) Validation of a new quality of life measure for children with epilepsy. Epilepsia 41:765–774

Speechley KN, Sang X, Levin S, Zou GY, Eliasziw M, Smith ML, Camfield C, Wiebe S (2008) Assessing severity of epilepsy in children: preliminary evidence of validity and reliability of a single-item scale. Epilepsy Behav 13:337–342

Smilkstein G (1978) The family APGAR: a proposal for a family function test and its use by physicians. J Fam Pract 6:1231–1239

Smilkstein G, Ashworth C, Montano D (1982) Validity and reliability of the family APGAR as a test of family function. J Fam Pract 15:303–311

Austin JK, Risinger MW, Beckett LA (1992) Correlates of behavior problems in children with epilepsy. Epilepsia 33:1115–1122

McCubbin HI, Thompson AI, McCubbin MA (1996) FIRM: family inventory of resources for management., Family assessment: resiliency, coping and adaptation Inventories for research and practiceUniversity of Wisconsin, Madison

McCubbin HI, Thompson AI, McCubbin MA (1996) FILE: family inventory of life events and changes., Family assessment: resiliency, coping and adaptation Inventories for research and practiceUniversity of Wisconsin, Madison

Campbell SB, Morgan-Lopez AA, Cox MJ, McLoyd VC (2009) A latent class analysis of maternal depressive symptoms over 12 years and offspring adjustment in adolescence. J Abnorm Psychol 118:479–493

Henderson AR (2005) The bootstrap: a technique for data-driven statistics. Using computer-intensive analyses to explore experimental data. Clin Chim Acta 359:1–26

Zou GY (2008) On the estimation of additive interaction by use of the four-by-two table and beyond. Am J Epidemiol 168:212–224

Zou GY, Donner A (2008) Construction of confidence limits about effect measures: a general approach. Stat Med 27:1693–1702

Jones BL, Nagin DS, Roeder K (2001) A SAS procedure based on mixture models for estimating developmental trajectories. Soc Methods Res 29:374–393

Jones BL, Nagin DS (2007) Advances in group-based trajectory modeling and a SAS procedure for estimating them. Sociol Method Res 35:542–571

Blackstone EH (2001) Breaking down barriers: helpful breakthrough statistical methods you need to understand better. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 122:430–439

Hughes S, Cohen D (2009) A systematic review of long-term studies of drug treated and non-drug treated depression. J Affect Disord 118:9–18

Muthen B (2004) Latent variable analysis. Growth mixture modeling and related techniques for longitudinal data. In: Kaplan D (ed) Handbook of quantitative methodology for the social sciences. Sage, Thousand Oaks

Bauer DJ, Curran PJ (2003) Distributional assumptions of growth mixture models: implications for overextraction of latent trajectory classes. Psychol Methods 8:338–363

Ferro MA, Speechley KN (2012) Depressive symptoms in mothers of children with epilepsy: a comparison of growth curve and latent class modeling. Health Serv Outcomes Res Method 12:44–61

Roeder K, Lynch KG, Nagin DS (1999) Modeling uncertainty in latent class membership: a case study in criminology. J Am Stat Asso 94:766–776

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. Bobby Jones for his assistance with PROC TRAJ. This research was funded by an operating grant to Dr. Kathy Speechley from the Canadian Institutes for Health Research (MOP-64311) and a Banting Postdoctoral Fellowship awarded to Dr. Mark Ferro.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ferro, M.A., Speechley, K.N. Stability of latent classes in group-based trajectory modeling of depressive symptoms in mothers of children with epilepsy: an internal validation study using a bootstrapping procedure. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 48, 1077–1086 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-012-0622-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-012-0622-6